Abstract

Reality is hierarchically structured, or so proponents of the metaphysical posit of grounding argue. The less fundamental facts obtain in virtue of, or are grounded in, the more fundamental facts. But what exactly is it for one fact to be more fundamental than another? The aim of this paper is to provide a measure of relative fundamentality. I develop and defend an account of the metaphysical hierarchy that assigns to each fact a set of ordinals representing the levels on which it occurs. The account allows one to compare any two facts with respect to their fundamentality and it uses immediate grounding as its sole primitive. In the first section, I will set the stage and point to some shortcomings of a rival account proposed by Karen Bennett. The second section will present my own proposal and the third section will discuss how it can be extended to non-foundationalist settings. The fourth section discusses potential objections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I will assume familiarity with the notion of grounding. For helpful introductions see Clark and Liggins (2012), Bliss and Trogdon (2016). I understand grounding as a relation between facts that takes pluralities of facts (the grounds) on the left and a single fact (the grounded) on the right. As it is customary, I’ll use square brackets to transform a sentence into a name of the fact the sentence expresses. Nothing in my argumentation hinges on there being a relation of ground, I could alternatively prefer to talk about grounding with the means of an operator that takes pluralities of truths on the left and a single truth on the right. For discussion of the distinction between the operator-approach and the predicate approach see Correia and Schnieder (2012) \(\S \) 3.1.

Two facts will be taken to be grounding-related iff one of them helps to ground the other.

See Bennett (2017) p. 138 for a related example.

Fine (2012) p. 51.

See Bennett (2017) ch. 6. Fabrice Correia presented an account of levels for logical grounding in a propositional language in Correia (2013) and Correia (2018). The scope of Correia’s account is restricted in a way the scope of the proposed account is not, for it only deals with cases of grounding that are due to the interaction between grounding and the truth-functional operators.

See Bennett (2017) ch. 2 for discussion.

Bennett (2017) p. 156.

The notion of a step of immediate grounding will play an important role in my account and will be further discussed below.

c.f. Bennett (2017) p. 161f: “there is nothing more to relations of greater and lesser fundamentality than the obtaining of certain patterns of building”. Of course, one might understand “patterns of grounding” as including the interaction between grounding and kinds of facts (or kinds invoked in facts), but there clearly is a more puristic notion of “patterns of grounding” available. Such a more puristic notion will be provided by the graph-theoretic treatment of patterns of grounding provided in the next section.

See Bennett (2019) p. 333.

Fine (2012) p. 50.

Fine (2012) p. 51.

The first conjuncts of both Disjunction and Conjunction are also used by Fine in his elucidation of the mediate/immediate-distinction (see Fine (2012) p. 51). The second conjuncts follow from Fine’s ground-theoretic elimination-rules. The rule for conjunction says that every strict full ground of \([p\wedge q]\) is a weak full ground of [p], [q]. To put it with Fine, the underlying thought is that “[w]e naturally want to say that any grounds for \([p\wedge q]\) should be mediated through [p] and [q]; the conjuncts are the conduit, so to speak, through which fact to the conjunction should flow.” Fine (2012) p. 63 (notation adjusted). A similar line of reasoning motivates that disjunctions don’t have any immediate partial grounds except for their disjuncts. As one reviewer pointed out, some might hold that some disjunctions have further grounds, e.g. that \([p\vee \lnot p]\) is grounded in e.g. the Law of Excluded Middle. Given that I use Disjunction not as an ingredient of my account, but rather as an assumption that helps to provide exemplary cases, it is safe to set this worry aside.

I borrow the notion of a grounding-pathway from Clark (2018).

Note that every sequence that has a first and a last element is a function whose domain is an interval of the integers that has a finite lower endpoint and a finite upper endpoint. Every interval of the integers that has a finite lower endpoint and a finite upper endpoint is of finite length. As a general rule, the cardinality of the interval [n, m] is \(m-n+1\).

Fine (2012) p. 51.

I will briefly discuss in footnotes how the account would have to be changed if this assumption were dropped. In this discussion, I will call a path such that some fact is the head of more than one of its elements a circular path.

If one allows for circular paths, then this condition should be replaced by the condition that every non-circular path is of finite length.

For discussion of the notion of ground-theoretical relevance see e.g. Krämer and Roski (2015).

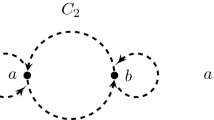

Generally, in addition to \(<\lbrace f_{1},g_{1}\rbrace , g>\), all and only the hyperedges that are of the form \(<\lbrace f_{i+1},g_{i+1}\rbrace , g_{i}>\) (for \(i\ge 1\)) are hyperedges of the graph. The nodes of the graph are \(f_{1},f_{2},\ldots , g,g_{1},g_{2},\ldots \).

A further potential worry against defining grounding simpliciter in terms of immediate grounding is that such a definition seems to rule out dense grounding (see e.g. Clark (2018) for this worry). The present scenario can be modified to show that it doesn’t. Take the set of facts \(F_{dense}\) to be such that there is a one-one mapping of these facts to the rational numbers such that for every two rational numbers i, j, if \(j>i\), then \(f_{i}\) (the fact mapped onto i) is fully grounded in \(f_{j}\) (the fact mapped onto j). This scenario behaves like the one presented in the main text, but it has the feature that the facts in \(F_{dense}\) are densely ordered by full grounding.

I thank an anonymous referee for pressing this point.

More precisely, for arbitrary \(f\in F\), \(M_{{\mathcal {G}}}(f)=M({\mathcal {G}},f)\).

These are fundamental facts, given that \({\mathcal {G}}\) witnesses how some fact is grounded in the fundamental.

Note that f is immediately partially grounded in g according to graph \({\mathcal {G}}'=\langle F',G'\rangle \) iff g is in the tail of a member of \(G'\) that has f as its head.

Every set of ordinals has a supremum, the smallest ordinal such that every ordinal in the set is not greater than it. This supremum might be an element of the set, its maximum, but it might also be a limit-ordinal that is not itself in the set. If you conceive of ordinals as pure sets along the lines suggested by John von Neumann, then the supremum of a set of ordinals is the union of its members.

According to the rule of amalgamation multiple full grounds of some f always form another full ground of f. If this rule holds, there is a further \({\mathcal {G}}_{3}\) that has \(\langle \lbrace [p] \rbrace ,[p \wedge p]\rangle \) and \(\langle \lbrace [p], [p\wedge p] \rbrace ,[p\vee (p \wedge p)]\rangle \) as hyperedges. This further grounding-graph works like \({\mathcal {G}}_{2}\), as far as the assignment of ordinals is concerned.

Here “E” is used as an existence-predicate that is true of an object iff the object exists.

According to Set, there is only one such graph.

This example also puts paid to the alternative simplistic idea that we count the shortest path from a fundamental fact to the target fact f, for this would yield the unacceptable result that [E(C)] is is on a level smaller than the smallest level of many of the facts it needs to be grounded.

Here’s a toy-example to prove the point. If the priority-structure of scenario w is completely described by the two non-well founded chains of full grounding \(\ldots< f_{-2}<f_{-1}<f_{1}<f_{2},\ldots \) and \(\ldots< g_{-2}<g_{-1}<g_{1}<g_{2},\ldots \), then any element of the first chain together with any element of the second chain forms a dummy-fundamental in this world.

For a position that acknowledges the existence of such a gigantic fact see Dasgupta (2009).

Note that for independent considerations, it might even be doubted that absolute fundamentality is a status that a fact has necessarily. See Wildman (2018) on this question.

There is a somewhat parallel discussion regarding the measurement of set-sizes. According to Cantorian accounts, sets are equal in size iff there is a one-to-one correspondence between them. According to Euclidean accounts, every set is larger than all of its proper subsets. For discussion see e.g. Parker (2013).

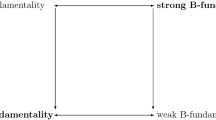

See Rabin (2018) p. 41f.

Rabin (2018) p. 42.

Rabin (2018) p. 41.

References

Bennett, K. (2017). Making things up. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bennett, K. (2019). Response to Leuenberger, Shumener and Thompson. Analysis, 79(2), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/anz004.

Bliss, R. (2014). Viciousness and circles of ground. Metaphilosophy, 45(2), 245–256.

Bliss, R., & Trogdon, K. (2016). Metaphysical grounding. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, winter. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Clark, M. J. (2018). What grounds what grounds what. Philosophical Quarterly, 68(270), 38–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/pq/pqx031.

Clark, M. J., & Liggins, D. (2012). Recent work on grounding. Analysis, 72(4), 812–823.

Correia, F. (2013). Logical grounds. Review of Symbolic Logic, 1, 1–29.

Correia, F. (2018). The logic of relative fundamentality. Synthese,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1709-8.

Correia, F., & Schnieder, B. (2012). Grounding: An opinionated introduction. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality (p. 1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dasgupta, S. (2009). Individuals: An essay in revisionary metaphysics. Philosophical Studies, 145(1), 35–67.

deRosset, L. (2015). Better semantics for the pure logic of ground. Analytic Philosophy, 56(3), 229–252.

Dixon, T. S. (2016). What is the well-foundedness of grounding? Mind, 125(498), 439–468.

Fine, K. (2012). Guide to ground. In B. Schnieder & F. Correia (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding (pp. 37–80). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krämer, S., & Roski, S. (2015). A note on the logic of worldly ground. Thought: A Journal of Philosophy, 4(1), 59–68.

Litland, J. E. (2015). Grounding, explanation, and the limit of internality. Philosophical Review, 124(4), 481–532.

Litland, J. E. (2016). An infinitely descending chain of ground without a lower bound. Philosophical Studies, 173(5), 1361–1369.

Litland, J. E. (2017). Grounding ground. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 10, 279–316.

Parker, M. W. (2013). Set size and the part-whole principle. Review of Symbolic Logic, 4, 1–24.

Rabin, G. O. (2018). Grounding orthodoxy and the layered conception. In G. Priest & R. L. Bliss (Eds.), Reality and its structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rabin, G. O., & Rabern, B. (2016). Well founding grounding grounding. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 45(4), 349–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-015-9376-4.

Raven, M. J. (2015). Fundamentality without foundations. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 93(3), 607–626.

Schaffer, J. (2009). On what grounds what. In D. J. Chalmers, R. Wasserman, & D. Manley (Eds.), Metametaphysics: New essays on the foundations of ontology (pp. 347–383). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shumener, E. (2019). Building and surveying: Relative fundamentality in Karen Bennett’s making things up. Analysis, 79(2), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/anz001.

Wildman, N. (2018). On shaky ground? In G. Priest & R. Bliss (Eds.), Reality and its structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the members of the colloquium Language and World at the University of Hamburg, the members of the eidos-colloquium at the University of Geneva, and the audiences at the conference The Logic and Metaphysics of Ground in Glasgow and the 7th CEU International Graduate Conference in Philosophy in Budapest. Special thanks go to Fabrice Correia, Zsolt Kapelner, Stephan Krämer, Stephan Leuenberger, Roberto Loss, Robert Michels, Stefan Roski and Lisa Vogt. Furthermore, I am grateful to two referees of this journal and to one referee of another journal for their constructive and friendly comments that very much helped to improve this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Werner, J. A grounding-based measure of relative fundamentality. Synthese 198, 9721–9737 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02676-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02676-2