Abstract

The “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard of proof, currently used in criminal trials, is notoriously vague and undermotivated. This paper discusses two popular strategies for justifying our choice of a particular precise interpretation of the standard: the “ratio-to-standard strategy” identifies a desired ratio of trial outcomes and then argues that a certain standard is the one that we can expect to produce our desired ratio, while the “utilities-to-standard strategy” identifies utilities for trial outcomes and then argues that a certain standard maximizes expected utility. I argue that both strategies fail on their own terms, by requiring us to perform calculations that we simply cannot perform. No version of either strategy can be performed by jurors or legislators in our actual epistemic position, in which, since we do not know which of the defendants in our trial system are genuinely innocent and which are genuinely guilty, we cannot determine the extent to which our trial system tends to produce evidence that misleadingly incriminates the innocent or misleadingly exonerates the guilty. But we would need to determine this in order to perform the calculations required by any possible version of the ratio-to-standard or utilities-to-standard strategies. I then suggest some empirical reasons to be pessimistic about the evidence produced by our actual trial system. The upshot is that the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard lacks a clear interpretation and rationale, nor do we have a promising way to identify an alternative. This is the trouble with standards of proof.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To make matters worse, these glosses are also at odds with the opinion of other courts. See e.g. Carr v. State, 23 Neb. 749, at 750 (1888), Morgan v. State, 48 Ohio St. 371, at 376 (1891) and State v. Cohen, 108 Iowa 208, at 214 (1899), all of whom deny that a reasonable doubt should be understood as a doubt for which a reason can be given.

A higher standard does not always produce fewer convictions, even holding evidence fixed. If the standard of proof increases from, say, 0.91 to 0.92, but there are no defendants whose degree of apparent guilt lies between 0.91 and 0.92, then this change to the standard of proof has no effect on the conviction rate. So the more accurate thing to say is that, holding evidence fixed, a higher standard of proof will yield an equal or greater number of convictions. If defendants’ degrees of apparent guilt are continuously distributed, then raising the standard always results in fewer convictions.

Some scholars have thought that claims about ideal ratios of trial outcomes can be directly translated into claims about the relative magnitude of the utilities of these outcomes; for example, Nagel (1979, p. 191) suggests that we can construe Blackstone’s ratio as saying “that it is ten times as bad to convict an innocent defendant as to acquit a guilty one”. This is an error. Being indifferent between ten false acquittals and one false conviction is not the same as the disutility of a single false conviction being ten times the disutility of a single false acquittal. This is because cardinal comparisons like “ten times as big” do not really make sense for utilities, since utility is measured on an interval scale. By analogy: there is no such thing as one temperature’s being “ten times as big” as another—someone using Celsius would say that 100° is ten times as hot as 10°, but someone using Fahrenheit would not think that 212° is ten times as hot as 50°, yet these expressions refer to the same temperatures. If someone is indifferent between ten false acquittals and one false conviction, what follows is that, on any scale, the disutility of ten false acquittals must be equal to the disutility of one false conviction for her. (This is what it is for her to be indifferent between the things.) This does not determine a scale-independent cardinal relationship between the disutility of two single trial errors.

Technically, a 10:1 ratio of false acquittals to false convictions is the one ratio that cannot have been Blackstone’s ideal, since he said that ten false acquittals are better than one false conviction, not that they are exactly equally bad. But it is now standard practice to refer to the 10:1 ratio as “the Blackstone ratio” or “Blackstone’s ratio”, so I will follow suit.

Laudan uses “SoP” as an abbreviation for “standard of proof”.

This is a strange choice, independently of my argument in this paper. Surely, in an ideal trial system, all innocent defendants will be acquitted and none will be convicted. So I struggle to see how an intuition about the ideal ratio of true acquittals to false convictions could rationalize our choice of a substantive standard of proof.

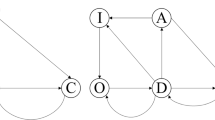

Note that this means that the curves cannot be interpreted as probability density functions. The relative height of the curves encodes information about the relative size of the two groups (guilty defendants and innocent defendants). So, the curves are more like the box diagrams of Fig. 1 than they are like probability density functions. The total area under the curves has probability 1, and the relative size of the areas representing each verdict shows the proportion of trials ending in that verdict.

Authors in the existing literature sometimes illustrate the Ratio-to-Standard strategy by stipulating values for the parts of their equations corresponding to the two distributions of apparent guilt and the proportion of people on trial who are genuinely guilty, and then deriving a suggested standard (typically 0.91—suspiciously similar to Blackstone’s ratio). But stipulation isn’t measurement. So, while these derivations are useful examples of how the Ratio-to-Standard strategy might go, they cannot tell us what the optimal standard of proof is in our own actual trial system.

Roberts’ target is officially the presumption of innocence, rather than the standard of proof, but he nonetheless has various proponents of the Ratio-to-Standard strategy in his sights. However, not all of his criticisms carry over. Most notably, he says that his primary objection to epistemic construals of the presumption of innocence is that, since we do not control our epistemic states, an injunction to believe that a defendant is innocent seems inappropriate. This does not apply to standards of proof, because they do not concern what someone ought to believe, but when they ought to return a guilty verdict—an action subject to the degree of voluntary control that we usually have over our actions.

As is the case if what is known as “the uniqueness thesis” in epistemology is false; see Kopec and Titelbaum (2016).

We might also want to estimate the impact of revisions to the standard of proof on the underlying proportion of people on trial who are genuinely guilty and the distributions of apparent guilt. One would expect police and prosecutors in systems with a higher standard to be more cautious about bringing a case to trial than those in systems with a lower standard, and to proceed only if the defendant’s apparent guilt is likely to be high. And, in that case, one might worry not only about mistaken verdicts but also about the kind of false negative that occurs when a genuinely guilty party is not brought to trial. Thanks to an anonymous referee for helpful discussion of this point.

As well as assessing the impact of particular factors on apparent guilt, we can assess the test/retest reliability of our system as a whole by “retrying” some cases in the lab. Thanks to the editors of Synthese for this suggestion.

I have been working on this paper for a very long time, during which I have discussed it with more people than I am now able to remember. I presented previous versions at the Harvard Graduate Legal Philosophy Symposium in March 2016, at the Stanford Legal Philosophy Workshop in December 2018, and in classes run by Scott Hershovitz at the University of Michigan and Daniel J. Singer at the University of Pennsylvania. I am grateful to participants at all of these events for formative discussion. Thanks also to Boris Babic for many lengthy conversations about this paper and related material over the years, to David Plunkett for a superlatively helpful debrief after the Stanford workshop, and to five anonymous referees. Most of all, thanks to Scott for believing in the paper all along.

References

Allen, R. (1977). The restoration of In Re Winship. Michigan Law Review, 76, 30.

Allen, R. (1993). Constitutional adjudication, the demands of knowledge, and epistemological modesty. Northwestern University Law Review, 88, 436.

Bell, R. (1987). Decision theory and due process: A critique of the supreme court’s lawmaking for burdens of proof. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 78, 557.

Blackstone, W. (1769). Commentaries on the laws of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Burnett v. State, 86 Neb. 11. (1910).

Butler v. State, 102 Wis. 364. (1899).

Carr v. State, 23 Neb. 749. (1888).

Commonwealth v. Webster, 59 Mass. 295. (1850).

Connolly, T. (1987). Decision theory, reasonable doubt, and the utility of erroneous acquittals. Law and Human Behavior, 11, 101.

Cullison, A. (1977). The model of rules and the logic of decision. In Nagel, S. (Ed.), Modeling the crimical justice system. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

DeKay, M. (1996). The difference between Blackstone-like error ratios and probabilistic standards of proof. Law & Social Inquiry, 21, 95.

Dervan, L., & Edkins, V. (2013). The innocent defendant’s dilemma: An innovative study of plea bargaining’s innocence problem. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 103, 1.

Devitt, E. J., et al. (1987). Federal jury practice and instructions. St. Paul: West Publishing Company.

Grann, D. (2009). Trial by fire. The New Yorker. Retrieved January 12, 2016 from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/09/07/trial-by-fire.

Hájek, A. (2007). The reference-class problem is your problem too. Synthese, 156, 563.

Kaplan, J. (1968). Decision theory and the factfinding process. Stanford Law Review, 20, 1065.

Kopec, M., & Titelbaum, M. G. (2016). The uniqueness thesis. Philosophy Compass, 11, 189.

Kramer, G., & Koenig, D. (1990). Do jurors understand criminal jury instructions? University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 23, 401.

Laudan, L. (2006). Truth, error, and criminal law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levinson, J. D., et al. (2010). Guilty by implicit racial bias: The guilty/not guilty implicit association test. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 8, 187.

Levinson, J. D., et al. (2013). Devaluing death: An empirical study of implicit racial bias on jury-eligible citizens in six death penalty states. New York University Law Review, 89, 513.

Levinson, J. D., & Young, D. (2010). Different shades of bias: Skin tone, implicit racial bias, and judgments of ambiguous evidence. West Virginia Law Review, 112, 307.

Lillquist, E. (2002). Recasting reasonable doubt: Decision theory and the virtues of variability. UC Davis Law Review, 36, 85.

Milanich, P. (1981). Decision theory and standards of proof. Law and Human Behavior, 5, 87.

Morgan v. State, 48 Ohio St. 371 (1891).

Nagel, S. (1979). Bringing the values of jurors in line with the law. Judicature, 63, 189.

National Research Council. (2009). Strengthening forensic science in the United States: A path forward. PDF document available from the National Academies Press, Retrieved August 12, 2016 from https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12589.html.

Rachlinski, J. J., et al. (2009). Does unconscious racial bias affect trial judges?. Cornell Law Faculty Publications, Paper 786.

Reichenbach, H. (1949). The theory of probability. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Roberts, P. (2020). Presumptuous or pluralistic presumptions of innocence? Methodological diagnosis towards conceptual reinvigoration. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02606-2.

Schauer, F. (2003). Profiles, probabilities, and stereotypes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Schmidt, M. S., & Apuzzo, M. (2015). South Carolina officer is charged with murder of Walter Scott. The New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2016 from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/08/us/south-carolina-officer-is-charged-with-murder-in-black-mans-death.html?_r=0.

State v. Cohen, 108 Iowa 208. (1899).

Stein, A. (2005). Foundations of evidence law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Strawn, D., & Buchanan, R. (1976). Jury confusion: A threat to justice. Judicature, 59, 478.

Tribe, L. (1971). Trial by mathematics: Precision and ritual in the legal process. Harvard Law Review, 84, 1329.

U.S. v. Martin-Tregora, 684 F.2d 485, at 493. (7th Cir. 1982).

Volokh, A. (1997). N guilty men. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 146, 193.

Walen, A. (2015). Proof beyond reasonable doubt: A balanced retributive account. Louisiana Law Review, 76, 355.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson King, Z.A. The trouble with standards of proof. Synthese 199, 141–159 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02639-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02639-7