Abstract

Judgementalism is an interpretation of normative decision theory according to which preferences are all-things-considered judgements of relative desirability, and the only attitudes that rationally constrain choice. The defence of judgementalism we find in Richard Bradley’s Decision Theory with a Human Face (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017) relies on a kind of internalism about the requirements of rationality, according to which they supervene on an agent’s mental states, and in particular those she can reason from. I argue that even if we grant such internalism, attitudes other than preferences in the judgementalist sense rationally constrain choice. This ultimately supports a different interpretation of preference.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

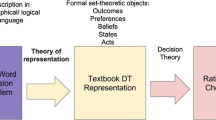

At the most general level, normative decision theory requires agents to have (or be representable as having) consistent preferences, and to choose in accordance with their preferences. But what are preferences, and what is the nature of these rational requirements? This paper offers an explication and a critique of an interpretation of normative decision theory developed in Bradley (2017) Decision Theory with a Human Face, which I will call ‘judgementalism’. According to judgementalism, preferences are judgements of relative desirability, and are the only attitudes that rationally constrain choice.

Extending Jeffrey-Bolker decision theory, Bradley’s book provides a powerful decision theoretic framework that can not only accommodate conditional attitudes, decision-making under various different kinds of uncertainty, and decision-making by agents that are bounded in various ways, but also yields several other decision theories (Savage, von Neumann-Morgenstern, and causal decision theory), as special cases. The book is moreover admirably explicit about its methodology and the intended interpretation of the core concepts of the decision theory it develops. While it is a very common conviction amongst decision theorists that preferences should be understood to be kinds of judgements, this interpretation of preference has rarely been defended as explicitly and in as much detail in the context of normative decision theory as in Bradley’s book.Footnote 1 It thus presents an opportunity for a critical discussion that I hope is of wider interest. Moreover, as we will see, our discussion will have important implications not only for what kinds of rational constraints are captured by Bradley’s and other standard theories of unbounded rationality, but also for the analysis of bounded rationality, which is a core concern of Bradley’s book.

I take judgementalism to be the conjunction of the following three claims: First, preferences are understood to be all-things-considered judgements about the relative desirability of different prospects. It is in relation to this interpretation of preference that Bradley himself introduces the term ‘judgementalist’ (p. 46). The second and third claims justify applying the term ‘judgementalist’ to the interpretation of normative decision theory more generally, as they assert the centrality of preferences within normative decision theory. The second claim is that binary preferences (along with judgements of relative credibility) take conceptual, explanatory and methodological priority over any numerical degrees of desirability or belief. And third, and connectedly, only an agent’s preferences, that is, her judgements of relative desirability, directly rationally constrain her choices. The first is a claim about the interpretation of preference in terms of judgements, the second asserts that preferences serve as the theoretical foundation of decision theory, and the third asserts their primacy in determining rational choice. Bradley endorses each of these claims in at least some parts of the book. My primary aim here is to consider the merits of this package of views, even though, as will become apparent in the following, it is not clear whether Bradley fully endorses each of these judgementalist claims in all parts of the book.

A core motivation for Bradley in endorsing each of the elements of judgementalism, I will show, is the idea that rational requirements supervene on agents’ mental states. That is, they capture a subjective kind of ‘ought’, ‘ought’ in the light of an agent’s beliefs, desires, and judgements. I will call this view internalism about the requirements of rationality. I will grant internalism about the requirements of rationality for the purposes of this paper. But internalism, I will show, does not entail judgementalism. There are attitudes other than preferences, as they are operationalised in normative decision theory, and understood in the judgementalist sense, that internalists can recognise as potential constraints on choice. Moreover, I will argue that they should do so, undermining the third judgementalist claim.

If attitudes other than preferences in the judgementalist sense can rationally constrain choice in their own right, then, I will argue, normative decision theory is better off also giving up the first, and central commitment of judgementalism, namely that preferences are judgements. I will propose an alternative that I think suits the internalist better, according to which preference is a relation that tracks all-things-considered subjective desirability, that is, desirability in the light of all the agent’s relevant attitudes. Crucially, preferences in this sense can be ascribed whether the agent has made a (correct) all-things-considered judgement of desirability or not (though she could arrive at a correct judgement through ideal deliberation).

2 Judgementalism

The decision theory developed in Decision Theory with a Human Face proposes, as all major decision theories do, that agents should choose in line with their preferences, that is, in the ideal case, choose one of their most preferred options (the “Choice Principle”, p. 25). Moreover—and this is what most of the discussion focuses on—a rational and unbounded agent’s preferences should have a certain kind of structure, whereby they can be thought of as tracking the expectation of a numerical measure of desirability or utility (the “Rationality Hypothesis”, p. 21). Bradley provides a representation theorem that shows that an agent’s preferences can be given such a desirability representation if and only if they abide by certain axioms—some of which Bradley goes on to relax later in the book to make room, e.g., for incomplete preference and imprecision. Preference is a binary relation, and notably, in Bradley’s framework, preference, just like the binary ‘at least as credible as’ relation, can have as its object any ‘prospect’, which could be a state of affairs, an outcome, an action, as well as a conditional possibility. Moreover, in the formal framework proposed, prospects are propositions which form an atomless Boolean algebra. My main concern here is the judgementalist interpretation Bradley gives to his framework. The following subsections will elaborate on each of the core commitments of judgementalism in turn.

2.1 Preferences are judgements

That preferences are to be understood as kinds of judgements is a claim Bradley returns to whenever the interpretation of his framework is explicitly discussed. Regarding the question of what these are judgements of, he primarily speaks of judgements of desirability (p. 28), but also of choice-worthiness (p. 47), betterness (p. 47), or benefit. However, in each of the latter three cases, it is made explicit that he has in mind choice-worthiness or value or benefit in light of the agent’s beliefs and desires. And likewise, the intended notion of desirability is presumably desirability of a prospect for the agent as an object of choice. According to judgementalism about preferences, preferences are judgements by an agent that some prospect a is more desirable than another prospect b as a potential object of choice for the agent. Bradley also stresses at various points (e.g. on p. 46) that preferences are meant to be ‘all-things-considered’ judgements that reflect all of an agent’s relevant reasons, agreeing here with Hausman (2012).

Two caveats should be noted. At one point in the book (pp. 46–47), Bradley proposes a ‘hybrid’ account of preference, whereby preferences are not only all-things-considered judgements of desirability, but also need to be instantiated in dispositions to choose. He there notes, “that they are also dispositions to choose both explains the connection between preference and choice and fixes the sense of betterness (namely as choice-worthiness) characteristic of preference judgements.” (p. 47) However, the Choice Principle arguably already explains the connection between preference and choice insofar as agents are rational, and fixes the sense of betterness characteristic of preference judgements—which also distinguishes preferences from other kinds of evaluative judgement. Given that the judgemental element of the hybrid account already removes the main potential advantage of dispositional accounts of preference, namely their parsimony, the addition of a dispositional element in Bradley’s account of preference seems unnecessarily restrictive. I will focus on the purely judgemental interpretation of preference in the following.

Secondly, Bradley defends the judgementalist account of preference primarily when decision theory is applied from the first person perspective, that is, when an agent is deliberating about what to do. While from the first person perspective, preferences are judgements of relative desirability, and, by the second judgementalist claim, utilities are graded judgements of of desirability, Bradley allows that from the third person perspective, preferences and utilities are given a different interpretation. Namely, they could be interpreted as denoting relative desire and degrees of desire respectively, rather than judgements about them (p. 28). He dubs this the ‘mental state interpretation’ of preference, and takes it to be different from judgementalism:

On the judgement interpretation, [the maximisation hypothesis] says that rationality requires of agents that they judge actions to be desirable to the degree that they can be expected to have desirable consequences, given how likely they judge the possible states of the world to be and how desirable they judge possible consequences. Similarly, on the mental state interpretation, the hypothesis says that an agent is rational only if the value she attaches to each action is its expected desirability, relative to her degrees of belief and desire. (pp. 28–29)

The mental state interpretation is more permissive, as we can ascribe desires and beliefs whenever we can identify something that plays the causal role of belief or desire in action explanation. And, to “play this role it is not essential that they be formed as a result of a conscious judgement on the part of the agent.” (p. 28) But as, according to Bradley, the formation of a judgement usually leads to the formation of a corresponding belief and desire, from the third person perspective, we might think of the judgement interpretation as just picking out special cases of the mental state interpretation.

As we will also see more in the following, for Bradley it is the first person perspective that is crucial for normative decision theory as a theory of rationality: Requirements of rationality are meant to be helpful to agents deliberating about what to do. And in the case of first person deliberation, Bradley takes the mental state interpretation to be inadequate. This is because an agent who is deliberating about what to do is not, or at least not only, looking inward to determine what her desires are, but rather is trying to figure out what options are actually valuable or desirable. In doing so, she makes judgements about the value or desirability of options. This value could be objective—Bradley is explicitly not committed to subjectivism about value. (pp. 29–30)

Aside from this distinction from the mental state interpretation, most of Bradley’s defence of judgementalism focuses on its advantages over two more radically different rivals: Interpretations that propose an objective or empirical interpretation of utility as, e.g., well-being or some other value; and choice-theoretic or dispositional accounts of preference and utility. Bradley’s case against objectivist interpretations of utility is one of the key instances where he appeals to what we will call internalism about the requirements of rationality.

On an objectivist interpretation of utility (and probability), standard decision theory would require agents to choose what in fact maximises expected well-being or value. But, according to Bradley, rationality cannot require an agent to do what is in fact expected to maximise well-being or value if she has false beliefs or makes mistaken judgements of (objective) value. For Bradley, rationality concerns only the questions of what it means for an agent to make consistent judgements, and to make the best choices given the judgements she has made. This is clearly compatible with making mistaken value judgements. All we can ask of agents is that they make the best choices given their judgements of credibility and desirability: “We are where we are, with the judgements that we have arrived at, and at the moment when the decision must be made the best that we can do is act consistently on the basis of those judgements.” (p. 27) Bradley’s remarks here exhibit an internalist conception of the requirements of rationality, which takes them to supervene on agents’ mental states. Rationality cannot require different things of two agents who have the same state of mind. More specifically, for Bradley, the requirements of rationality supervene on the agent’s judgements of desirability and credibility.Footnote 2

Bradley’s core defence against the proponent of choice-theoretic interpretations of preference as disposition to choose is that only mental states and judgements, not choices, are “the sorts of things that are susceptible to rationality conditions.” (p. 46) Given the Choice Principle does rationally constrain choice, Bradley must have in mind here the rational consistency conditions of the Rationality Hypothesis. In line with the third defining claim of judgementalism, the idea is that choice is only rationally constrained by preference judgements, and not subject to its own consistency conditions.

2.2 Preferences are prior

The second defining claim of judgementalism is that preferences and judgements of relative credibility have conceptual, explanatory and methodological priority over any numerical notions featuring in decision theory, such as utilities, or, in Bradley’s framework, desirabilities and probabilities. They are thus the fundamental relations decision theory is based on. Bradley calls this view ‘pragmatism’ (p. 43). Methodological priority is given to preferences as they typically form the empirical basis for ascription of the quantitative notions. And conceptual priority is given to preference because the properties of rational preference are supposed to explain the properties of the quantitative notions. Against the background of one’s favoured representation theorem, the plausibility of the axioms on preference is supposed to explain the properties of the desirability or utility functions that capture the preferences. This is a natural view to take when, as Bradley does, one takes the rationality conditions on relational attitudes like preference to have more intuitive appeal than the properties of quantitative notions like utility, probability and desirability.

Bradley provides two further considerations in favour of pragmatism. One is that “agents are not typically in a position to make precise numerical cognitive or evaluative judgements. Nor does rationality require that they do so.” (p. 72) If agents are more often in a position to make relational judgements of relative desirability or credibility, this seems to count in favour of pragmatism. Secondly, Bradley argues that models formulated in terms of quantitative notions like desirability and probability will arise as a special case of relational ones: If preferences are complete and consistent, then a quantitative model representing them can be generated. If they are not, there will be no precise quantitative model. Given this latter possibility, relational models also have greater generality. (pp. 72–73)

While Bradley is quite clear about his judgementalism about preference, and about taking preferences to be conceptually and explanatorily prior to the quantitative notion of desirability, I’d like to point out here an important ambiguity regarding how quantitative desirabilities are to be interpreted. Quantitative desirabilities are measures that make it meaningful to compare the size differences between options. Yet, they are meant to be conceptually derivative of binary judgements. Despite the name, on the judgementalist picture, we can’t think of these desirabilities as a measure of actual desirability, that is, of the thing preferences are meant to be judgements of. If they were, then preference, which is a judgement of desirability, would not be conceptually and explanatorily prior to it. Unless, that is, judgements of desirability are what determines desirability. However, as we have just seen, Bradley explicitly rejects such subjectivism about value.Footnote 3

But it is not entirely clear how else we should think of quantitative desirabilities within a judgementalist framework. Elsewhere (Bradley 2004), Bradley suggests that desirabilities track degrees of preference, and that thus preference has more than a binary structure after all. But it is not clear how we should think of degrees of preference when preferences are judgements. Two possibilities are the following: First, we could think of them as a measure of degrees of desirability, as judged by the agent, that is, as expressing the agent’s judgements about degrees of desirability rather than just about orders of desirability. Second, we could think of them as expressing degrees of judgement of desirability. In the first case, it is the desirability (as judged by the agent) that is graded. In the second case, it is the judgement itself that is graded.

An interpretation along the second lines would require further explication, as it is not immediately obvious what it would mean to make a judgement of degree x that some option a is desirable, and whether judgements come in degrees at all. It would be implausible for such degrees to track the confidence with which a judgement is made, since agents might be equally confident in all their evaluative judgements, even if some of them are represented by lower utility assignments. At least an agent can be equally confident in all her relational judgements, i.e. preferences, and then it is unclear again how these relational judgements should be explanatorily and conceptually prior to ascriptions of varying degrees of confidence in one’s evaluative judgements.

The first judgementalist interpretation of utility/desirability is somewhat easier to make sense of, and it seems plausible that relational judgements about orders of desirability should be explanatorily and conceptually prior to judgements of degrees of desirability. But the more fundamental problem with both ways of thinking of desirabilities or utilities as capturing some kind of graded judgement is that ascribing utilities and desirabilities to an agent now means ascribing additional judgements to her, different from the relational judgements we started out with. We can either think of judgements as necessarily conscious, or as potentially unconscious, implicit in other judgements we have made. If they are necessarily conscious, it’s implausible that the desirability and utility assignments yielded by the representation theorems should always represent quantitative judgements. After all, an agent who makes consistent relational judgements can conceivably not make any conscious quantitative judgements at all. In fact, as we have just seen, one of the reasons Bradley endorses pragmatism to begin with is that agents are often in a position to make relational judgements when they can’t make precise numerical judgements, at least not consciously.

This problem would be avoided if we thought of judgements as not necessarily conscious. At one point (p. 65), Bradley indeed suggests that judgements need not be conscious. But in many parts of the book, Bradley relies on judgements being necessarily conscious. As noted above, he appeals to conscious awareness of judgements to distinguish judgementalism from mental state accounts. Moreover, much of the book is concerned with the representation of incomplete preferences, where preferences are incomplete when agents have not made up their mind about an issue, for instance because they have not thought about it due to cognitive limitations (pp. 225–226). The standard for preference ascription Bradley applies here thus seems to presuppose a conscious judgement. Lastly, and most importantly for our discussion, for the most part, Bradley considers normative decision theory from the first person perspective, as a tool for decision makers to figure out what to do. And decision makers can only reason from the judgements they are conscious of. In fact, we will see in the next section that appealing to the connection of rationality to reasoning and action-guidance is the most plausible case for internalism about rational requirements, which serves as a justification for other judgementalist claims.

Thus, some of Bradley’s central claims rely on judgements being necessarily conscious, but in that case, the claim that desirability and utility ascriptions denote additional kinds of judgements seems undermined. A final possibility is that quantitative desirabilities are not a measure of anything graded at all, but rather merely a convenient way of representing relational judgements of desirability. This corresponds to what is arguably the standard interpretation of utility in the economics literature, which sees utility as a mere convenient representation of preference.Footnote 4 On this view, there would be no implication at all that desirabilities track degrees of judgement, or degrees of desirability as judged by the agent. The quantitative measure would express only facts about the structure of the agent’s relational judgements. Pragmatism not only makes sense, but indeed is implicit in this interpretation of quantitative desirabilities and utilities. I thus take this to be the best way forward for the judgementalist. However, this third possibility appears to be rejected by Bradley: He thinks that desirabilities are a quantitative measure of some graded attitude.

All in all, then, there is tension between Bradley’s pragmatism, the commitment that judgements are conscious implicit in some central arguments in the book, and his insistence that desirabilities and utilities represent some graded attitude. Given I am treating pragmatism as a central claim of judgementalism, and the central role of internalism about rationality in justifying judgementalism, I think it is the latter that should be given up by the judgementalist. I will set these complications aside for now, however. What is crucial about pragmatism from a judgementalist perspective is that quantitative notions such as utility or desirability do not rationally constrain preference, because preference is explanatorily prior to these. According to the third judgementalist claim, discussed in the next section, they also do not constrain choice in their own right—only preference does so.

2.3 Only preferences constrain choice

The final defining claim of the judgementalist position is that only preferences, conceived of as relational judgements, directly constrain choices. Bradley proposes the Choice Principle, and only the Choice Principle as a rational requirement on an unbounded agent’s choices, and the Choice Principle asks agents to choose one of their most preferred options. The Choice Principle has to be relaxed in cases of incomplete preferences. But here, too, the recommendations of the potential choice rules discussed by Bradley supervene on the imprecise utility representation of the agent, which in turn, given pragmatism, is simply derived from the preferences the agent does have. Preferences themselves are only constrained by other preferences and relational judgements of credibility. This is the view Bradley calls, following Broome (1991), ‘moderate Humeanism’.Footnote 5 Despite the initial appearance that the Rationality Hypothesis constrains preferences by requiring them to conform to the expectation of benefit, Bradley conceives of the Rationality Hypothesis as merely a requirement of consistency on preferences. In line with the representation theorems, agents should have preferences that are representable as expected desirability/utility maximising.

Why think that only preferences in the judgementalist sense constrain choices? The lazy answer is that this just follows from the first two judgementalist claims in combination with what the formal framework of normative decision theory gives us—one which has proven to be very fruitful, as Bradley’s book amply demonstrates. But to say more, we can appeal again to internalism about the requirements of rationality. As we already saw above, Bradley appears to be committed specifically to the view that rational requirements supervene on judgements, from which it follows that only judgements rationally constrain choice. Preferences being kinds of judgements according to the first judgementalist claim, this might be seen to support this third judgementalist claim.

Let me sum up the judgementalist interpretation of decision theory and Bradley’s motivations for endorsing it. According to judgementalism, preferences are all-things-considered relational judgements of desirability, they are conceptually and explanatorily prior to, and not rationally constrained by any quantitative notions like utility and desirability, and only preferences thus interpreted rationally constrain choices. That preferences are judgements rather than desires is motivated by a rejection of subjectivism about value, as deliberating agents are attempting to figure out, not determine what is in fact desirable. And that they are judgements rather than tracking objective value directly is motivated by internalism about rational requirements, according to which rational requirements supervene on mental states, and in particular judgements. The judgementalist claim that preferences are conceptually and explanatorily prior to quantitative desirabilities and utilities is motivated by the claims that rationality conditions on relational judgements have greater intuitive appeal, that we more easily make relational than quantitative judgements, and that starting from relational judgements yields the more general theory. And the judgementalist claim that only preferences constrain choices is motivated again by internalism about the requirements of rationality.

On this picture, normative decision theory is meant to govern decision-making from the first person perspective, which is assumed to proceed roughly as follows: To choose rationally, I must choose in line with my all-things-considered judgements about what it would be most desirable to do. When making these judgements, my aim is to correctly capture what is in fact desirable, not, or at least not exclusively to determine what is desirable. But when figuring out what all-things-considered judgement of desirability to make, all I can subjectively appeal to are other judgements I have made—of relative desirability and of relative credibility. If rationality only imposes subjective norms, then these can only be norms that appeal to consistency among my judgements, and consistency of my choices with my judgements. The best I can do is make a judgement that is consistent with my other judgements, and then act accordingly. And, crucially, requirements on the preferences and credibility judgements as they feature in the formal framework of normative decision theory are supposed to fully capture this picture of rational choice.

3 Motivations for internalism about requirements of rationality

Internalism about rational requirements is central to the justification of judgementalism. Preferences should not be understood in terms of some objective measure of desirability, because agents may not know what is actually most desirable. If rational requirements need to supervene on mental states, then no rational requirements should be formulated directly in terms of an objective measure of desirability. Instead, Bradley holds, preferences should be understood as judgements, which are mental states. That preferences in the judgementalist sense should be the only things that constrain choice also seems to be motivated by a kind of internalism about rational requirements. In this Sect. 1 consider what might be a plausible justification for internalism about rational requirements, which points to what a plausible internalism would look like. This then serves as the basis for my argument, in the following sections, that internalism does not imply judgementalism, and that internalists in fact shouldn’t be judgementalists about normative decision theory.

The most explicit defence Bradley gives of internalism about rational requirements appeals to a kind of ‘ought implies can’ thesis (p. 27). That defence, however, seems to overshoot its target. What he seems to have in mind is something like the following: If, in order to non-accidentally choose in accordance with some ‘ought’ claim, I need to know something I don’t know and can’t figure out on the basis of the beliefs and preferences I have, then the ‘ought’ claim can’t apply to me. Or at least, this ‘ought implies can’ claim is true of the rational ‘ought’. The problem with this version of ‘ought implies can’ is that it rules out too much. In particular, it would imply that it is not true that those who have false views about the requirements of rationality themselves—such as the requirements of consistency Bradley defends—rationally ought to abide by the true requirements of rationality. But presumably Bradley wants to say that agents rationally ought to abide by the requirements of rationality, whether they can know what they are or not. For instance, an agent with intransitive preferences who does not believe intransitivity to be irrational would, presumably, still be regarded irrational by Bradley. Otherwise, it seems, his theory would only be normative for the kinds of agents that already believe in it.

It thus can’t be characteristic of the kind of normativity theories of rationality are about that it is constrained by the kind of ‘ought implies can’ claim just described. We can’t avoid distinguishing between the kinds of mistaken attitudes or judgements that rationally exculpate, and those that don’t. At the very least, mistaken views about rationality don’t seem to rationally exculpate (just as mistaken views about morality don’t ordinarily morally exculpate). What the judgementalist wants to say, presumably, is that being mistaken about the requirements of rationality, and being mistaken on the basis of inconsistency are the only kinds of mistaken attitudes that do not rationally exculpate. Mistaken views about morality, on the other hand, do—it is not a rational mistake to have the wrong objective values.

Instead of an ‘ought implies can’ thesis, I think the most plausible way to justify this is to insist that the purpose of rational norms and requirements is to give first-personal guidance, and that rationality thus must be connected to reasoning in a particular way: The advice the theory of rationality gives must be advice the agent can follow without any further external input. Once she knows what the requirements of rationality are, she must be able to figure out how to abide by them through reasoning on the basis of her existing attitudes alone. Moreover, in the context of normative decision theory, which ultimately aims at choice, rational requirements should be action-guiding, so that they help agents figure out what to do on the basis of reasoning from their existing mental states.

In addition to being implied by Bradley at various points in his book, this kind of view is indeed common in the literature on rationality. Recently, Broome (2013) has defended both the views that requirements of rationality supervene on the mind, and that rationality is essentially connected to reasoning. The specific kind of internalism about rational requirements that results from this view of rationality is that rational requirements supervene on not just any mental state, but rather just the kinds of mental states that we can reason from—otherwise there might be rational requirements that agents cannot figure out how to abide by through reasoning.Footnote 6

Preferences in the judgementalist sense, and judgements of relative credibility arguably are such attitudes we can reason from, at least if we take them to be necessarily conscious. The problem for judgementalism is that they are not the only attitudes we can reason from. Internalism thus does not imply judgementalism. The next two sections will argue that in fact the internalist about rational requirements should allow for attitudes other than judgementalist preferences to constrain choice. I will argue that, while this does not necessarily commit decision theory to starting to explicitly model these other kinds of attitudes, it does undermine the judgementalist interpretation of decision theory.

4 Rational norms about decision frames

The first problem for the internalist justification of judgementalism I would like to raise is that requirements formulated in terms of the kinds of judgements Bradley takes preferences to be are not actually action-guiding on their own. They are only action-guiding in conjunction with requirements appealing to other kinds of mental states. The source of the problem is that agents must first represent the decision problem they are facing in some way before knowing which of their judgements are even relevant for determining what to do. That is, they must specify what the prospects are they are choosing between.

It is generally acknowledged that there are better or worse ways of representing one’s decision problems. In fact Bradley’s book contains a fairly detailed discussion of the problem of how to frame one’s decision problems (pp. 13–16). He presents this problem in terms of a trade-off between quality and efficiency of choice. Efficiency is about minimising the cognitive labour of decision-making, and generally speaks against decision frames that are too complex. Quality, on the other hand, depends on including as many relevant features in the description of the decision problem as possible. Bradley here speaks of the need to include the most relevant features of the possible outcomes of choices that matter to agents, and features of the environment on which the outcomes depend, as the “correctness” of the decision depends on this (p. 14).

These remarks seem eminently reasonable. However, they also arguably commit Bradley to rational constraints on choice other than preferences in the judgementalist sense. First of all, the kinds of norms in question here seem to evidently be norms of rationality. Bradley speaks of the correctness of a decision depending on including the most relevant features of outcomes, where presumably the sense of correctness is rational correctness. When an agent strikes a grossly inadequate balance between efficiency and quality in formulating her choice problem, that is, fails to include the most important features of her decision situation, and then acts on her judgements regarding this decision problem, this seems to be a rational failing—what other kind of failing would it be? When I frame my decision problem regarding whether or not to take an umbrella without taking into account whether or not it is going to rain (even though I have beliefs about the weather, and I take it to be highly relevant to my choice), my resulting choice will be straightforwardly irrational unless it happens to coincide with what I would have judged had I taken everything relevant into account. It will be irrational even if my judgements are coherent and I act in accordance with the Choice Principle. Norms about framing thus introduce additional rational constraints on choice.

Importantly, these failings can be rational failings even for the internalist, as long as the norms about framing can themselves be specified in internalist terms. They arguably can be formulated in internalist terms. But, problematically for the judgementalist, we can’t express these norms in terms of only preferences in the judgementalist sense. Following remarks about including in prospect description features that ‘matter’ to agents, when elaborating on what makes a feature relevant to include, Bradley writes, “[a] feature of the state of the world or of a consequence is relevant to a decision problem if the choice of action is sensitive to values that we might reasonably assign to this feature (its probability or utility).” (p. 15) Given the judgementalist commitment to pragmatism, which takes preferences to be conceptually and explanatorily prior to utility and desirability, one might attempt to reduce this to a claim about preferences in the judgementalist sense: A feature is relevant to include when the agent’s judgements are very sensitive to its inclusion in the description of the decision problem. But this would be in conflict with Bradley’s reasonable comments about efficiency of decision-making: On this reading, agents can only make relevance assessments when they can appeal to their judgements regarding more complex representations of a decision problem. But if they can appeal to those already, there is no efficiency tradeoff in adopting a more complex representation. However, this efficiency tradeoff is indeed very real, as in fact we don’t standardly come equipped with judgements about very complex prospects.

One could adopt a hypothetical judgement reading of relevance now, and suppose that a factor is relevant if it would significantly impact the agent’s judgements. But appealing to hypothetical judgements would make relevance something that cannot be directly assessed or determined by the agent by reasoning from the attitudes and judgements she actually starts out with. Relevance norms for the specification of decision problems would thus violate internalism about rational requirements.

Judgementalism meets a dead end here. Judgementalism is motivated in large part by internalism about the requirements of rationality, and the idea that any norms of rationality need to be action-guiding. But in order for decision theory to be action-guiding, we need norms about the framing of decision problems. And these cannot plausibly be formulated in purely judgementalist terms, at least not without giving up internalism about the requirements of rationality. Within an internalist framework, the best way forward, I suggest, is to take attitudes regarding relevance to be an additional kind of attitude, different from preference, that introduces its own rational constraints.

On the view I want to suggest, when deliberating about a decision, agents start out with attitudes (let them be judgements) about which of the properties of their choice situation matter to them, and with views about which of them are more important than others. On the basis of these judgements, and taking into account efficiency, they formulate their decision problem, which specifies the prospects to be chosen between. They then make/consult their judgements about which prospect is most desirable. What is important here is that the initial judgements of relevance can not be preferences in the decision-theoretic sense, as they do not have prospects as their object. Rather, they have as their object properties of the agent’s choice situation as the agent perceives it. In fact, we can consult these judgements before we have even formulated what prospects we are choosing between. They concern not prospects, but candidate properties for being included in the description of the prospects we are choosing between. So norms about framing appeal to attitudes other than preferences over prospects, and we said these norms introduce additional rational constraints on choice, other than coherence norms on preference and the Choice Principle. If choice is rationally constrained by attitudes other than judgementalist preference, we need to give up the third defining feature of judgementalism.

An example will help in bringing out the difference between preferences and the judgements of relevance I have in mind. Suppose I am trying to figure out what boat to buy. It might be initially hard for me to compare the various different boats on offer, but I might have a clear idea about the properties of the boat that matter to me, say, price, longevity, performance, and design aesthetics. And I might have some idea about the factors that affect these, e.g., the condition of the wood and the sail. These can then inform the formulation of the prospects involved in choosing one of the boats on offer. These prospects should include descriptions of all the properties of the choice situation that I have judged significantly relevant. Once I have formulated the prospects, I can form, or consult a judgement about the relative desirability of prospects thus described. But my original judgements about the properties that are important to me are not judgements concerning prospects. They concern properties of my choice situation, and thus candidates for the inclusion in the description of prospects.Footnote 7

For decision theory to be action-guiding in the way the internalist about rational requirements would like it to be, we thus must give up the third judgementalist claim and allow for attitudes other than preferences to constrain choices. If we relax this claim along the lines I have suggested, there is a particular kind of irrational choice that stems not from a failure to act in accordance with one’s preferences understood as one’s judgements of desirability, or a failure of consistency in preference. It stems from the failure to take into account properties of one’s choice situation that matter to oneself, that one judges relevant, when formulating one’s decision problem.

This was the first core reason I want to present for rejecting judgementalism, and in particular its third defining claim. One might think that this just commits us to a minor relaxation of judgementalism. We will see below why this relaxation is not as minor as it might seem. For now, note also that once we have acknowledged that preferences are not the only attitudes that constrain choices in this one respect, further constraints from other sources become salient. As has already played a role here, one thing that is special about the attitudes the judgementalist takes to be the only attitude rationally constraining choices is that they are judgements that have prospects as their objects. But agents may be constrained by attitudes, including judgements, about objects that are not prospects. The next section argues that this is more generally so.

5 What all-things-considered judgements are based on

The relevance judgements just discussed are one type of attitude that do not have prospects as their object, but that nevertheless seem to rationally constrain us. To see that there are other such attitudes, consider the fact that Bradley takes preferences to be ‘all-things-considered’ judgements. This raises the question of what the things are that are considered when we are making these judgements. The term suggests that we are reasoning from various different considerations to an overall evaluation. If we are reasoning from these, they must be attitudes the internalist can at least in principle appeal to when formulating requirements of rationality. Intuitively, what we do is take into account all the relevant subjective reasons (reasons as we see them) for favouring one prospect or another. For instance, when I decide which boat to buy, I consider my subjective reasons relating to the price, longevity, performance and design aesthetics of the boats on offer.

The problem for judgementalism now is that the attitudes that pick out these subjective reasons can’t be preferences as they are understood in Bradley’s framework. For one, if preferences are all-things-considered judgements, then surely they are based on attitudes that are not yet all-things-considered, but rather partial. Moreover, preferences, in Bradley’s and Jeffrey’s framework, have prospects as their object. As mentioned above, prospects are modelled as propositions in Bradley’s and Jeffrey’s frameworks, and form a Boolean algebra. A simple proposition like ‘I own a mahogany boat’ is equivalent to a disjunction of sub-prospects that form a jointly exhaustive list of ways in which it might be true that I own a mahogany boat, for instance ‘I own a mahogany boat and it cost more than the down-payment on a house’ or ‘I own a mahogany boat and it did not cost more than the down-payment on a house’.

A boat’s being made of mahogany might well be one of the things that I take into account when making an all-things-considered judgement about what boat to buy. Suppose I find mahogany aesthetically pleasing in a boat, so I take its being made of mahogany to count in favour of choosing a particular boat. It is one of my subjective reasons, in this case one that counts in favour of any mahogany boat. But it would be a mistake to say that a judgement about the prospect ‘I own a mahogany boat’ is what makes this a subjective reason to be taken into account when I make an all-things-considered judgement regarding the prospect of owning a specific mahogany boat, along with judgements about analogous prospects for the other features I care about, e.g. ‘I own a leaky boat’. The prospect of owning a specific leaky mahogany boat is actually a sub-prospect of the prospect ‘I own a mahogany boat’. And so, if anything, my judgement about the specific leaky mahogany boat is one of the things to consider when making a judgement about the prospect ‘I own a mahogany boat’, not the other way around. And my judgement about the prospect ‘I own a mahogany boat’ is going to be affected by my views about all the mahogany boats that are not leaky, which are largely irrelevant in this instance. My attitude to the prospect ‘I own a mahogany boat’ is thus not the kind of thing that would enter as one of many reasons when making an all-things-considered judgement about a specific mahogany boat.

What all-things-considered judgements are based on, rather, are attitudes that give us only a partial assessment of a prospect, which can then be combined with other partial assessments to offer a full assessment. Attitudes to prospects of which the prospect to be assessed is a sub-prospect are not partial in this way. Instead, all-things-considered judgements about prospects seem to be based on attitudes to properties—of the boat, and of any state of affairs where I own it. If we grant that these attitudes are still desirability judgements, the idea is that not only prospects, but also properties can be desirable, potential bearers of value. When I judge mahogany boats to be desirable, I am not making a judgement about the collection of states of the world in which it is true I own a mahogany boat. I know that any such state of the world will have many other properties I care about, and that may affect how I evaluate the disjunction of all those states of affairs. When I express a positive judgement about mahogany, I am abstracting away from all of those other features.

Suppose I think mahogany boats are overwhelmingly going to be too expensive for me. I might then judge the prospect ‘I own a mahogany boat’ to be quite undesirable (the proposition is only likely to be true if I have either bankrupted myself or the boat is leaky). Or suppose I have some vague and uncertain memory that there may be ethical or environmental concerns regarding mahogany, and thus withhold judgement on the prospect of owning a mahogany boat. In both cases, it might still be true that I judge that, insofar as aesthetics are concerned, its being made of mahogany counts in favour of any boat under my consideration, and take this into consideration when making an all-things-considered judgement.

When making an all-things-considered judgement of desirability about some prospect, we seem to make it on the basis of how desirable we find the properties of this prospect.Footnote 8 Another remark about all-things-considered judgements will be important in the following. And that is that all-things-considered judgements don’t seem to provide us with additional reasons, on top of the reasons they are based on. Rather, they aim to establish what the sum of all of our reasons supports. Granted, some considerations that may form subjective reasons only become apparent when various different properties interact. Mahogany might be tacky in combination with some boat designs. But this is best thought of in terms of additional, more complex properties of the relevant prospect, rather than the all-things-considered judgement adding reasons for action not contained in the reasons on the basis of which it is formed. All-things-considered judgements are different in kind from other judgements because they sum up, rather than provide new subjective reasons.

Some passages in Bradley’s book suggest that he agrees with this picture of all-things-considered judgements being based on subjective reasons. He speaks explicitly of preferences being formed on the basis of reasons for favouring one option or the other (p. 46), and acknowledges that such reasons are different from preferences. He suggests, however, that this deepens, but does not displace preference-based explanation (p. 161).

But, as our previous observations about framing, these observations do speak at least against the third judgementalist commitment, and thus don’t only deepen, but call for revisions to judgementalist decision theory. At least they do so if we take there to be rational requirements relating to the attitudes to properties that all-things-considered judgements are based on that constrain choice in their own right. And there evidently are such requirements. If I judge a boat all of whose properties (that I judge relevant) I find highly undesirable to be all-things-considered more desirable than a boat all of whose properties (that I judge relevant) I find very desirable, I make a bad judgement. And when I act on this judgement, I make an irrational choice. If I choose the boat with the (subjectively) undesirable properties over the boat with the (subjectively) desirable properties, I chose irrationally, even if I made a corresponding (false) all-things-considered judgement, and even if I made no all-things-considered judgement at all.

This example was not chosen for its realism, but merely to bring out that there are rational requirements relating to attitudes to properties, which can directly and indirectly constrain choice. We might not know what they are in any detail, especially when it comes to less clear-cut cases. And standard normative decision theory, which deals in preferences over prospects, does not have anything to say about them. My argument is not that these need to be explicitly included in formal decision theory. Rather, it is that their existence undermines the judgementalist interpretation of decision theory. And these requirements are compatible with internalism about the requirements of rationality, as judgements about properties are attitudes that agents can reason from, with the help of the relevant rationality principles. Section 7 will present an alternative non-judgementalist interpretation of standard decision theory that, I argue, best accommodates the existence of these requirements while remaining thoroughly internalist. First, however, I want to argue that judgementalism can’t deal with the problems I have raised with a few minor tweaks.

6 Judgementalist rejoinders

We might be tempted to think that all we need to acknowledge in response to my arguments is that there are additional requirements of rationality that we are leaving out when we focus only on the Rationality and Choice Principles understood in judgementalist terms. Decision theory, more generally, was never supposed to provide a complete account of practical rationality, and so this alone is not much of a problem. According to this view, completing judgementalist decision theory to provide a full account of rationality is unproblematic: we merely need to add to judgementalist decision theory additional principles regarding how judgements about properties rationally constrain all-things-considered judgements. These different kinds of rational requirements, it might be thought, can be treated largely independently, perhaps by other branches of philosophy, while retaining the judgementalist interpretation of preference. I think there are two main ways of making this case: (a) One could hold that standard decision theoretic requirements of preference consistency and preference-guided choice hold only for agents who have formed correct all-things-considered judgements. Or (b) one could suppose that the Choice Principle expresses a narrower kind of ‘ought’ than the full rational ‘ought’: It is about doing well in the light of the judgements about prospects one has formed, be they rational or not.

I don’t think either of these attempts to save judgementalist decision theory is satisfactory. The difficulty for these views arises because attitudes to properties don’t only rationally constrain all-things-considered judgements (and thus choice indirectly), but, as I argued, constrain choices directly as well. This is what creates the conflict with the third judgementalist commitment. The problem with the two judgementalist rejoinders (a) and (b) just described is best highlighted by considering again two kinds of cases. First, a case where I make no all-things-considered judgement regarding the two boats with the overwhelmingly undesirable and overwhelmingly desirable properties, respectively, at all (and either preference would be consistent with all my other preferences). And secondly, a case where I have made the wrong all-things-considered judgement in favour of the boat with the overwhelmingly undesirable properties.

According to (a), decision theory makes no definite recommendation in either case. The analysis of the first case would depend on whether agents are required to have formed all relevant all-things-considered judgements, or whether their judgements can remain incomplete (as Bradley accepts). If it is the former, decision theory does not apply, and if it is the latter, the agent remains unconstrained in her choice due to incompleteness. Regarding the second case, featuring a mistaken all-things-considered judgement, (a) implies decision theoretic requirements don’t apply. A proponent of (a) might even claim that rational choice is impossible for an agent in such a situation, as she is in an overall inconsistent judgemental state—as is sometimes claimed of agents with intransitive preferences. According to (b), decision theory again leaves the agent in the first case unconstrained in her choice. And in the second case, (b) suggests that there would be a sense, the narrow, decision theoretic sense, in which the agent should act on her mistaken all-things-considered judgement, even if she fully rationally ought not.

But, in line with what I argued in the last section, the following seems to be a better analysis of these cases: In both cases, I am rationally constrained by my attitudes to the properties of the boats to pick the one with the overwhelmingly desirable properties. In the first case, this may or may not involve first forming an all-things-considered judgement along these lines. In the second case, this may involve counter-judgemental choice or first revising one’s judgement. And so both (a) and (b) get the first case wrong by leaving the agent’s choices unconstrained unless she forms an all-things-considered judgement. (a) gets the second case wrong because it either remains silent or suggests rational choice is impossible unless the agent revises her judgement. (b)’s analysis of the second case, on the other hand, is implausible because it is unclear what this ‘ought’ which is narrower than the full rational ‘ought’, and may conflict with the full rational ‘ought’, should be. I find it hard to see that there should be any sense in which I ought to act on my mistaken all-things-considered judgement even if I rationally ought to do something else. Moreover, if possible, such proliferation of different kinds of ‘ought’ should be avoided.

This is not to say that there isn’t something that goes wrong when an agent forms a mistaken judgement, even if she nevertheless chooses rationally (by choosing counter-preferentially). She has made a mistaken all-things-considered judgement, and thus committed an error of reasoning. While her choice was rational in the end, her mental processes were not fully rational. But the important point it that the mistaken all-things-considered judgement neither changes what the agent rationally should do nor makes rational choice impossible for her. This is because, as we noted above, all-things-considered judgements don’t create additional reasons for an agent. They are merely attempts to weigh her various subjective reasons. The judgement about where the balance of subjective reasons lies does not change where this balance in fact lies.

Where does this leave the judgementalist framework? I think that, at best, what we can say within a judgementalist framework is that the Choice Principle holds only conditionally on our all-things-considered judgements standing in the right relations to our subjective reasons (in line with the relevant rationality requirements). If we have made (subjectively) correct all-things-considered judgements, then we should act on them. If not, the rational choice is still the one, or one of the ones that would be supported by a correct all-things-considered judgement. But if that is the case, it seems like we can dispense with the Choice Principle, understood in judgementalist terms, alltogether. We can simply say that rational choice is choice in line with whatever the correct all-things-considered judgement based on our subjective reasons would be—regardless of what all-things-considered judgements we have actually made (though we might still want to independently condemn incorrect judgements as bad reasoning).

Giving up the third defining feature of judgementalism in the way that we have argued for thus does not only point to the incompleteness of judgementalist decision theory. It also means one of the central principles of normative decision theory, namely the Choice Principle and its relaxations under incompleteness, would need to be substantially qualified, or would even turn out redundant. The next section will argue that there is a way forward which preserves internalism about the requirements of rationality, as well as the Choice and Rationality Principles as Bradley develops them. It moreover allows decision theory to continue to black-box the question of what preferences are based on if it wishes to, or leave this to other branches of philosophy or the decision sciences. It thus accommodates both core features of standard decision theory, as well as a core philosophical commitment about rationality shared by Bradley and many decision theorists—internalism about the requirements of rationality. However, it involves giving up the first, and arguably central defining claim of judgementalism.

7 An alternative to judgementalism

On the alternative to judgementalism I wish to suggest to the internalist here, preferences are not judgements of desirability, but rather track what I will call subjective all-things-considered desirability. Subjective all-things-considered desirability supervenes on the agent’s subjective reasons, the reasons the agent recognises on the basis of her beliefs and judgements of desirability (where these have as their object properties). Agents can determine what is subjectively all-things-considered desirable by reasoning on the basis of their subjective reasons. Still, the important difference between this view of preference and the judgementalist one is that it ascribes preferences to agents independently of what all-things-considered judgements they actually make, if they make one at all. Preference itself does not track a specific attitude or judgement of the agent’s, but rather tracks what all-things-considered judgement they should arrive at ideally through deliberation on the basis of their subjective reasons. If there is no unique all-things-considered judgement that is supported by the agent’s subjective reasons, this could be captured by an imprecise framework as Bradley develops it.

If we apply the Rationality and Choice Principles to this interpretation of preference (in the unbounded case), normative decision theory requires that subjective desirability abides by the consistency axioms of the theory, e.g. that relational subjective desirability is transitive, and that agents should act so as to maximise subjective desirability. Note that normative decision theory based on this interpretation of preference still expresses only internal rational requirements. Agents have the resources to figure out what is subjectively most desirable by consulting their subjective reasons, and the requirements of rationality. If they make a mistake in doing so, this is a rational failing. Even if they don’t know what the requirements of rationality are—and indeed little has been said on how all-things-considered subjective desirability of prospects relates to judgements about and attitudes to properties—not acting in accordance with what is subjectively most desirable is still a rational failing. To connect this to our earlier discussion, mistaken judgements of subjective desirability do not rationally exculpate (even if mistaken judgements about objective value do).

The advantage of this interpretation of preference is that the Rationality and Choice Principles now accommodate the ways in which we have argued relevance judgements and attitudes to properties of prospects constrain choice: An agent who acts on a mistaken all-things-considered judgement, or fails to make the correct choice when she has not made the all-things-considered judgement that tracks subjective desirability, would run afoul of the reconceived Choice Principle. Our earlier worries about framing can also be naturally accommodated now. Choosing the option with highest subjective all-things-considered desirability is naturally interpreted as choosing the option that is most desirable taking into account everything one judges relevant, that is, all one’s relevant subjective reasons. When applying normative decision theory under this interpretation, prospects should thus be described in a way that captures everything the agent judges relevant. And then when an agent fails to take into account some factor she judges relevant in her reasoning process, she is again likely to run afoul of the Choice Principle. The advantage of this interpretation of preference is thus that the Choice Principle accurately parses rational from irrational choice for any kind of irrationality internalists should recognise.

This is not to say that normative decision theory isn’t still incomplete. To give a complete characterisation of the requirements of rationality, we would have to know how subjective reasons and all-things-considered desirability relate, and I have not filled this in. But given that the kinds of irrational choices stemming from mistaken formation of all-things-considered judgement and inadequate framing are rational failings and should be recognised as such by the internalist (whether we can specify what requirements they violate or not), it is best to make room for them in a way that doesn’t let them undermine the recommendations of the Choice Principle. The resulting decision theory does not need to be qualified or restricted to agents who have not made such mistakes. It just requires agents to engage in reasoning governed by rationality principles not spelled out in standard normative decision theory in order to figure out what specific choice it is that the Choice Principle recommends. This reinterpretation of preference clarifies and strengthens the role normative decision theory would play in a complete account of practical rationality, without stopping decision theorists from black-boxing questions of preference formation in their work.

While the alternative interpretation of normative decision theory I have proposed does not require a revision of the Rationality and Choice Principles, or an expansion of the kinds of questions decision theory deals with, it does have substantive implications for decision theorists. For one, as we have seen, it changes what recommendations decision theory makes in cases where all-things-considered judgements about prospects are mistaken. It also introduces an additional layer of uncertainty for agents and decision analysts, as any advice of the theory will depend on whether the agent’s or the analyst’s all-things-considered judgement correctly reflects the agent’s subjective reasons. However, it strikes me that this is how it should be; the recommendations of decision theory should come with such a caveat. And, as I have argued above, including such a caveat does not violate internalism.

Moreover, and importantly for Bradley’s project, the alternative interpretation of preference I have proposed also changes how we should think about incompleteness of preference. For the judgementalist, preferences are incomplete whenever an agent has not made an all-things-considered judgement about some choice-relevant prospects. And, whenever they are incomplete, which we can expect to be the case quite frequently, agents are only constrained by the all-things-considered judgements they have made. On the account I have proposed, incompleteness is going to be less frequent: At least some of the time, when an agent has not made an all-things-considered judgement about a prospect, there is still a fact of the matter as to what all-things-considered judgement would be supported by all her subjective reasons. The agent simply has not made the corresponding judgement (yet). In such cases, a preference can still be ascribed on my account. The question we need to ask when determining whether preferences are incomplete, is whether an agent’s underlying subjective reasons leave it indeterminate which of two prospects should be favoured. I believe agents do find themselves in such situations, for instance when their underlying attitudes are vague. But this phenomenon will be less frequent. And, again, it seems as it should be to reserve imprecise decision theory to this more specific phenomenon, as it is just in this case that rationality is intuitively permissive.

8 Conclusions

According to the judgementalist interpretation of normative decision theory, preferences are all-things-considered judgements of desirability, explanatorily and conceptually prior to any quantitative notion of of utility or desirability, and the only attitudes that rationally constrain choice. Judgementalism seems to be motivated by internalism about rational requirements. But I have argued that even the internalist about rational requirements should reject judgementalism. Attitudes other than preferences in the judgementalist sense rationally constrain choice, and this ultimately renders a different interpretation of preference more plausible for the internalist.

Early on in Decision Theory with a Human Face, Bradley distinguishes between two interpretations of the Choice Principle: Doing what is in one’s best interest, on the one hand, and doing “what one thinks is best, all things considered, in the light of one’s beliefs and preferences” (p. 25). He endorses the latter, and rejects the former on the basis that it yields rational requirements that are not internal. What I have argued here is that internalism about rational requirements more plausibly supports a third alternative, namely that the Choice Principle demands that agents do what is best, all-things-considered, in the light of their beliefs and judgements of desirability.

Notes

That this kind of internalism about the requirements of rationality is compatible with objectivism about value is argued in Asarnow (2016).

Moreover, even if the agent’s relational judgements of desirability always tracked actual desirability, it would still be unclear why the quantities that represent an agent’s judgements of relative desirability as per the representation theorem should at the same time provide a quantitative measure of actual desirability, as opposed to simply a quantitative measure of judgements of desirability.

See, e.g., Binmore (2008, pp. 19–22) on the ‘causal utility fallacy’.

The appeal to Humeanism is slightly misleading given the role Bradley grants to objective value. Humeanism in practical reason is usually associated with the idea that reasons need to have some basis in desire. See, e.g., Schroeder (2007). But Bradley seems to allow for the possibility that judgements of objective value provide reasons for action even in the absence of a desire, or even if a corresponding desire only arises because of the judgement of objective value.

Lee (2018) argues on this basis that rational requirements govern only occurrent mental states.

The next section will discuss in more detail why attitudes to properties of prospects can’t be reduced to attitudes to prospects.

References

Asarnow, S. (2016). Rational internalism. Ethics, 127(1), 147–178.

Binmore, K. (2008). Rational decisions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bradley, R. (2004). Ramsey’s representation theorem. Dialectica, 58(4), 483–497.

Bradley, R. (2017). Decision theory with a human face. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Broome, J. (1991). Weighing goods. Oxford: Blackwell.

Broome, J. (2013). Rationality through reasoning. Hoboken: Wiley.

Hausman, D. (2012). Preference, value, choice, and welfare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, W. (2018). Reasoning, rational requirements, and occurrent attitudes. European Journal of Philosophy, 26(4), 1343–1357.

Pettit, P. (1991). Decision theory and folk psychology. In M. Bacharach & S. Hurley (Eds.), Foundations of decision theory: issues and advances (pp. 147–175). Oxford: Blackwell.

Schroeder, M. (2007). Slaves of the passions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johanna, T. (2019a). In defence of revealed preference theory. Unpublished manuscript.

Johanna, T. (2019b). Folk psychology and the interpretation of decision theory. Unpublished manuscript.

Acknowledgements

I thank Richard Bradley and an anonymous referee for very valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this paper, and Liam Kofi Bright and Anna Mahtani for very helpful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thoma, J. Judgementalism about normative decision theory. Synthese 198, 6767–6787 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02487-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02487-0