Abstract

To understand something involves some sort of commitment to a set of propositions comprising an account of the understood phenomenon. Some take this commitment to be a species of belief; others, such as Elgin and I, take it to be a kind of cognitive policy. This paper takes a step back from debates about the nature of understanding and asks when this commitment involved in understanding is epistemically appropriate, or ‘acceptable’ in Elgin’s terminology. In particular, appealing to lessons from the lottery and preface paradoxes, it is argued that this type of commitment is sometimes acceptable even when it would be rational to assign arbitrarily low probabilities to the relevant propositions. This strongly suggests that the relevant type of commitment is sometimes acceptable in the absence of epistemic justification for belief, which in turn implies that understanding does not require justification in the traditional sense. The paper goes on to develop a new probabilistic model of acceptability, based on the idea that the maximally informative accounts of the understood phenomenon should be optimally probable. Interestingly, this probabilistic model ends up being similar in important ways to Elgin’s proposal to analyze the acceptability of such commitments in terms of ‘reflective equilibrium’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is true for ‘objectual’ as well as ‘explanatory’ understanding, so my discussion in this paper applies to both kinds of understanding—if indeed they really are distinct (see Khalifa 2013a).

I will use ‘commit’ in what follows, although this can be replaced with ‘appeal’ throughout for those who prefer that terminology.

Of course, to say that understanding involves acceptance rather than belief is not to say that belief could not play any role at all in how or why an agent comes to understand something. Rather, it means that belief is not necessary for understanding—that one could understand something without believing the propositions on which the understanding is based.

My own view is that this is not a convincing reason to move from belief to acceptance, since idealizations function as a tool for gaining understanding rather than as part of the content of what is committed to in understanding something. See Lawler (2018) for a proposal along these lines.

See footnote 21 below.

Another terminological option would be to use terms that are traditionally associated with epistemically appropriate beliefs, e.g. ‘rational’, ‘reasonable’ or ‘warranted’, but this would have the opposite effect of misleadingly indicating that the commitment involved in understanding is assumed to be a species of belief.

In idealizations, there is some claim or part of a claim that is radically false, as when we suppose that a population is infinite or that an object is moving on a frictionless plane. In approximations, there is some claim or part of a claim that is ‘close to the truth’, as when we round up or down to the nearest integer for a given quantity or suppose that a nearly spherical object (such as a planet) is in fact a perfect sphere.

Indeed, if it were impossible to qualify a given idealization/approximation in this way—if there was no ‘translation key’ which could be used to convert the statement into something that isn’t known to be false—then the falsehood would not really be felicitous in the first place; it would just be an ordinary (known) falsehood (Bokulich 2012, pp. 731–736).

For dissent, see Khalifa (2016).

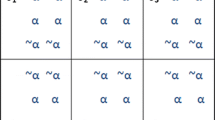

I am not quite suggesting that any two acceptable commitments can be ‘conjoined’ into an acceptable conjunctive commitment; rather, I am suggesting that this type of conjunction principle holds when the commitments in question are made in the context of understanding the very same phenomenon. To see why this matters, note that there might very well be cases in which it would be acceptable for an agent to commit to \(P_1\) in understanding \(X_1\), and also acceptable for the agent to commit to \(P_2\) in understanding \(X_2\), but it wouldn’t be acceptable to commit to \((P_1 \wedge P_2)\) in understanding anything. For example, perhaps it would be acceptable for current physicists to commit to general relativity in understanding gravitational lensing, and to quantum mechanics in understanding the emission spectrum of hydrogen, but not acceptable to commit to the conjunction of general relativity and quantum mechanics, e.g. because the two theories are seemingly inconsistent.

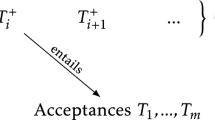

That is, we can use mathematical induction in which the inductive step consists in using the two-proposition principle to obtain that it would be acceptable to commit to \((P_1 \wedge \cdots \wedge P_{i+1})\) if it would be acceptable to commit to \((P_1 \wedge \cdots \wedge P_i)\) and \(P_{i+1}\) respectively.

However, not much in what follows turns on making this generalization however. In particular, the arguments for separating acceptability and justification in the next section use only the restricted principle (\(\wedge \)) and not also the more general (\(\Rightarrow \)).

Although I use the traditional terms for the two paradoxes, the cases that I use to illustrate the two paradoxes will not mention either lotteries or prefaces. In my view, these features of Kyburg’s and Makinson’s original examples distract from the relevant logical points about the relationship between probability and justified belief. For example, it seriously misleading in my view to focus on the fact that the lottery paradox involves making a ‘statistical inference’ (Nelkin 2000), since the logical structure of the lottery paradox can be manifested by bodies of propositions that involve no statistical information at all (see my version of the case below).

I note in passing that this argument also puts pressure on the idea that understanding requires belief, i.e. that the commitment involved in understanding is belief or a species thereof. For if the commitment involved in understanding were a species of belief, then epistemic justification would presumably at least be a necessarily condition on epistemically appropriate commitment of this kind. By contrast, if the commitment involved in understanding is not a species of belief, then we should expect it to be possible for the epistemic conditions for each type of attitude to come apart in some cases (in accordance with the current argument).

That said, the threshold t cannot depend on the probability assigned to the proposition P itself or logically related propositions, since one could then simply ‘solve’ the problem by appropriate stipulation of thresholds for each proposition. This is roughly what Leitgeb (2014, 2017) proposes to do in a systematic way with his ‘stability theory’ of belief. I lack the space here to consider Leitgeb’s proposal in detail, but suffice it to say that Leitgeb’s theory makes the choice of threshold depend on factors about the agent that seem to me to be entirely irrelevant to whether she would be justified in believing the propositions in question (in any recognizable sense of ‘justified’), such as which partition the agent happens to consider (see Leitgeb 2014, pp. 152–160).

A parellel point is true of explanation: Some propositions are not even potential explanantia of a given explanandum.

How to finish this list will clearly depend on the specifics of one’s theory of understanding, e.g. on whether one takes understanding to require explanation—an issue we leave open here.

This is meant to mirror van Fraassen’s (1980) framework for thinking about scientific explanations, where a potential explanation is identified with an answer to a specific kind of question, viz. an explanation-seeking why-question. Indeed, again mirroring van Fraassen, an ‘understanding-seeking question’ can simply be identified with its potential answers in the manner of a Hamblian account of questions (Hamblin 1973).

Here and in what follows, I mean to be deliberately non-committal regarding whether a noetic account needs to entail an answer to all actual understanding-seeking questions (i.e. those that we are actually interested in, or that are actually salient for us at a given time) or all possible understanding-seeking questions (i.e. all understanding-seeking questions in logical space). I don’t know of any convincing reason to prefer either version of the definition, so I prefer not to be committed either way on this issue.

One might object that in most cases when we attribute understanding to someone, the understanding agent will never have thought of many of the noetic accounts of the relevant phenomenon. After all, noetic accounts will in many cases be enormously complicated constructions—much more complicated than we can reasonably take ordinary agents to cognize—so my definition of a ‘noetic account’ may seem to make it impossible for ordinary agents to satisfy the demands set by the model. This objection is misplaced, for reasons that will become clearer below. For now, suffice it to say that the role of the concept of a ‘noetic account’ is not to be the content of the type of commitment that’s involved in understanding, but rather to be a piece of theoretical machinery that determines—in conjunction with other pieces of the machinery—when such commitments are normatively appropriate. Thus while a ‘noetic account’ must satisfy certain normative conditions in order for an agent’s commitments to be acceptable, the agent need never have actually committed to the noetic account itself in order for her commitments to be acceptable.

A related point worth making here is that the Optimality Model is an ‘externalist’ theory of acceptability in the sense that it will often be difficult, and sometimes even impossible, for an agent to tell whether a given proposition is acceptable for her. That said, the agent may well make educated guesses about acceptability by a number of routes, e.g. by asking herself whether any remotely probable noetic account would entail the proposition (if not, she has some grounds for taking the proposition not to be acceptable). Note also that the Optimality Model is perfectly compatible with the idea that acceptability supervenes on the relevant agent’s mental or evidential state. (Whether the model entails such a supervenience will depend on what interpretation of probability one chooses to adopt—see below.) So while the Optimality Model is ‘accessibility externalist’, it is at least compatible with ‘mentalist internalism’. (Thanks to Christoph Baumberger for discussion of this point.)

Note that, on this interpretation, the probability of P for an agent S does not represent the actual credence that S assigns to P. Even if 0.7, say, is the credence that it is rational for S to assign to P, S may have some credence other than 0.7 in P, or indeed no (precise) credence at all.

I leave open the possibility that rational credences must conform to other norms as well, e.g. norms connecting credences to physical chances such as the Principal Principle (Lewis 1980), norms connecting credences to symmetry considerations such as the Principle of Indifference (Laplace 1951; Keynes 1921) and the Maximum Entropy Principle (Jaynes 2003; Rosenkrantz 1977), or even norms that constrain rational credences based on explanatory considerations (Huemer 2009; Weisberg 2009).

As I note below, I do not argue here for requiring strong as opposed to weak probabilistic optimality for acceptability. Rather, I leave this as an open question to be answered by considerations that fall outside the scope of this paper.

It is perhaps worth contrasting the ratio-based interpretation suggested here with another salient possibility for interpreting ‘significantly more probable’. Consider a difference-based approach, according to which \(N_X^i\) is taken to be significantly more probable than \(N_X^j\) just in case \(Pr(N_X^i) > d + Pr(N_X^j)\) for some \(0< d < 1\). Now, this does not accord with the standard mathematical interpretation of ‘\(\gg \)’, but then again we shouldn’t let mathematical practice dictate our model of rational understanding. The real problem with a difference-based approach is that it smuggles in a probability-threshold of the kind we have already rejected (see Sect. 3). For note that on this approach the probability of any noetic account N must exceed d (whatever it is) in order for a proposition that follows from it to be acceptable, so d effectively becomes a probability-threshold. (Yet other interpretations of ‘significantly greater’ are of course possible, e.g. in terms of exponential functions rather than ratios or differences. I leave it to future work to explore which (if any) of these other interpretations would result in notions of strong probabilistic optimality that are better or worse suited for our purposes here.)

I am indebted to an anonymous reviewer for this example.

I am deeply indebted and extremely grateful to an anonymous Synthese reviewer for suggesting this approach to proving the following results. My original proof strategy was considerably more cumbersome and less illuminating.

I am very grateful to Christoph Baumberger, Chris Dorst, Insa Lawler, and two anonymous reviewers, who all provided extraordinarily insightful comments on previous drafts of this paper. I am also indepted to my colleagues at Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences for helpful comments and illuminating discussions about this paper. Finally, I am grateful to the audience at Innsbruck University’s workshop on Elgin’s True Enough, and to Kate herself for inspiration, discussion, and encouragement.

References

Akiba, K. (2000). Shogenji’s probabilistic measure of coherence is incoherent. Analysis, 60, 356–359.

Baumberger, C. (2019). Explicating objectual understanding: Taking degrees seriously. Journal for General Philosophy of Science. (forthcoming)

Bengson, J. (2015). A noetic theory of understanding and intuition as sense-maker. Inquiry, 58, 633–668.

Bokulich, A. (2012). Distinguishing explanatory from nonexplanatory fictions. Philosophy of Science, 79, 725–737.

Carter, J. A., & Gordon, E. C. (2014). Objectual understanding and the value problem. American Philosophical Quarterly, 51, 1–13.

Cohen, L. J. (1992). An essay on belief and acceptance. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Cooper, N. (1994). Understanding. Aristotelian Society Supplementary, 68, 1–26.

Dellsén, F. (2017). Understanding without justification or belief. Ratio, 30, 239–254.

Dellsén, F. (2018a). Beyond explanation: Understanding as dependency modeling. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science,. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axy058.

Dellsén, F. (2018b). Deductive cogency, understanding, and acceptance. Synthese, 195, 3121–3141.

Elgin, C. Z. (2004). True enough. Philosophical Issues, 14, 113–131.

Elgin, C. Z. (2007). Understanding and the facts. Philosophical Studies, 132, 33–42.

Elgin, C. Z. (2009). Is understanding factive? In A. Haddock, A. Millar, & D. Pritchard (Eds.), Epistemic value (pp. 322–330). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elgin, C. Z. (2017). True enough. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fitelson, B. (2003). A probabilistic theory of coherence. Analysis, 63, 194–199.

Foley, R. (1992). The epistemology of belief and the epistemology of degrees of belief. American Philosophical Quarterly, 29, 111–124.

Foley, R. (2009). Belief, degrees of belief, and the lockean thesis. In F. Huber & C. Schmidt-Petri (Eds.), Degrees of belief (pp. 37–47). Dordrecht: Springer.

Frigg, R., & Nguyen, J. (2016). The fiction view of models reloaded. The Monist, 99, 225–242.

Gijsbers, V. (2015). Can probabilistic coherence be a measure of understanding. Theoria: Revista de Teoría Historia y Fundamentos de la Ciencia, 30, 53–71.

Greco, J. (2014). Episteme: Knowledge and understanding. In K. Timpe & C. A. Boyd (Eds.), Virtues and their vices (pp. 285–302). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grimm, S. (2006). Is understanding a species of knowledge? British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 57, 515–535.

Grimm, S. (2011). Understanding. In S. Bernecker & D. Pritchard (Eds.), Routledge companion to epistemology (pp. 84–94). London: Routledge.

Grimm, S. (2014). Understanding as knowledge of causes. In A. Fairweather (Ed.), Virtue epistemology naturalized: Bridges between virtue epistemology and philosophy of science (pp. 347–360). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hamblin, C. L. (1973). Questions in montague English. Foundations of Language, 10, 41–53.

Hills, A. (2016). Understanding why. Nous, 50, 661–688.

Huemer, M. (2009). Explanationist aid for the theory of inductive logic. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 60, 345–375.

Jaynes, E. T. (2003). Probability theory: The logic of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kelp, C. (2015). Understanding phenomena. Synthese, 192, 3799–3816.

Kelp, C. (2017). Towards a knowledge-based account of understanding. In S. Grimm, C. Baumberger, & S. Ammon (Eds.), Explaining understanding: Perspectives from epistemology and philosophy of science (pp. 251–271). New York, NY: Routledge.

Keynes, J. M. (1921). A treatise on probability. London: Macmillan.

Khalifa, K. (2013a). Is understanding explanatory or objectual? Synthese, 190, 1153–1171.

Khalifa, K. (2013b). Understanding, grasping, and luck. Episteme, 10, 1–17.

Khalifa, K. (2016). Must understanding be coherent? In S. Grimm, C. Baumberger, & S. Ammon (Eds.), Explaining understanding: Perspectives from epistemology and philosophy of science (pp. 139–164). London: Routledge.

Khalifa, K. (2017). Understanding, explanation, and scientific knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kvanvig, J. (2003). The value of knowledge and the pursuit of understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kyburg, H. E. (1961). Probability and the logic of rational belief. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Laplace, P.-S. (1951). A philosophical essay on probabilities. New York: Dover.

Lawler, I. (2016). Reductionism about understanding why. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 116, 229–236.

Lawler, I. (2018). Scientific understanding and felicitous legitimate falsehoods. Unpublished manuscript.

Leitgeb, H. (2014). The stability theory of belief. Philosophical Review, 123, 131–171.

Leitgeb, H. (2017). The stability theory of belief. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1980). A subjectivist’s guide to objective chance. In R. C. Jeffrey (Ed.), Studies in inductive logic and probability (Vol. 2, pp. 263–93). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Makinson, D. C. (1965). The paradox of the preface. Analysis, 25, 205–207.

Mizrahi, M. (2012). Idealizations and scientific understanding. Philosophical Studies, 160, 237–252.

Nelkin, D. K. (2000). The lottery paradox, knowledge, and rationality. The Philosophical Review, 109, 373–409.

Olsson, E. J. (2005). Against coherence: Truth, probability, and justification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pritchard, D. (2009). Knowledge, understanding, and epistemic value. In A. O’Hear (Ed.), Epistemology (royal institute of philosophy lectures) (pp. 19–43). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Riggs, W. D. (2009). Understanding, knowledge, and the meno requirement. In A. Haddock, A. Millar, & D. H. Pritchard (Eds.), Epistemic value. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosenkrantz, R. D. (1977). Inference, model and decision: Towards a Bayesian philosophy of science. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Schupbach, J. N. (2011). New hope for Shogenji’s coherence measure. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 62, 125–142.

Shogenji, T. (1999). Is coherence truth-conducive? Analysis, 59, 338–345.

Shogenji, T. (2001). Reply to Akiba on the probabilistic measure of coherence. Analysis, 61, 147–150.

Simon, H. A. (1956). Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review, 63, 129–138.

Sliwa, P. (2015). Understanding and knowing. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 115, 57–74.

Strevens, M. (2017). How idealizations provide understanding. In S. Grimm, C. Baumberger, & S. Ammon (Eds.), Explaining understanding: New essays in epistemology and philosophy of science (pp. 37–49). New York: Routledge.

Sullivan, E., & Khalifa, K. (2019). Idealizations and understanding: Much ado about nothing? Australasian Journal of Philosophy,. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048402.2018.1564337.

van Fraassen, B. C. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford: Clarendon.

Weisberg, J. (2009). Locating IBE in the Bayesian framework. Synthese, 167, 125–143.

Wilkenfeld, D. A. (2016). Understanding without believing. In S. Grimm, C. Baumberger, & S. Ammon (Eds.), Explaining understanding: Perspectives from epistemology and philosophy of science (pp. 318–334). New York: Routledge.

Wilkenfeld, D. A. (2018). Understanding as compression. Philosophical Studies,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1152-1.

Zagzebski, L. (2001). Recovering understanding. In M. Steup (Ed.), Knowledge, truth, and duty (pp. 235–252). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dellsén, F. Rational understanding: toward a probabilistic epistemology of acceptability. Synthese 198, 2475–2494 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02224-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02224-7