Abstract

In this paper I argue that pluralism at the level of logical systems requires a certain monism at the meta-logical level, and so, in a sense, there cannot be pluralism all the way down. The adequate alternative logical systems bottom out in a shared basic meta-logic, and as such, logical pluralism is limited. I argue that the content of this basic meta-logic must include the analogue of logical rules Modus Ponens (MP) and Universal Instantiation (UI). I show this through a detailed analysis of the ‘adoption problem’, which manifests something special about MP and UI. It appears that MP and UI underwrite the very nature of a logical rule of inference, due to all rules of inference being conditional and universal in their structure. As such, all logical rules presuppose MP and UI, making MP and UI self-governing, basic, unadoptable, and (most relevantly to logical pluralism) required in the meta-logic for the adequacy of any logical system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to a metaphysical reading of logical pluralism, there is a plurality of correct logics (as opposed to only one, as the logical monist says). A more epistemic reading of logical pluralism, however, can be dated back to Carnap:

… in logic there are no morals. Everyone is at liberty to build up his own logic, i.e., his own form of language, as he wishes.Footnote 1

This is otherwise known as Carnap’s Principle of Tolerance:

… let any postulates and rules of inference be chosen arbitrarily; then this choice, whatever it may be, will determine what meaning is to be assigned to the fundamental logical symbols… The standpoint we have suggested —we will call it the Principle of Tolerance… — relates not only to mathematics, but to all questions of logic.Footnote 2

In order for this Principle to make sense, there must be a plurality of logics for us to be tolerant towards that are equally worthy of being chosen. A metaphysical reading of logical pluralism thus seems to be entailed by the epistemic Principle of Tolerance, and requires that there be alternative logics to be pluralistic about.

I will speak of logical systems to describe formal systems with rules of inference, and take logical pluralism to be a thesis about these logical systems. So what qualifies something as a logical system such that there could be many different (but relatively similar in order to class as) instances of them that are equally true? This is related to the opening of Beall and Restall’s paper ‘Logical Pluralism’:

Anyone acquainted with contemporary Logic knows that there are many so-called logics. But are these logics rightly so-called? Are any of the menagerie of non-classical logics, such as relevant logics, intuitionistic logic, paraconsistent logics or quantum logics, as deserving of the title ‘logic’ as classical logic? On the other hand, is classical logic really as deserving of the title ‘logic’ as relevant logic (or any of the other non-classical logics)?Footnote 3

Rather than answering whether these logics are ‘rightly so-called’, I tackle a more epistemological question as to whether they are equally worthy of being chosen. I answer that they are not, due to the metaphysical reason that some logics are not as adequate as others, where inadequacy is due to deviance from what I argue is a core, basic, meta-logic.Footnote 4 Without certain meta-logical content, the logic is useless and thus not as equally worthy of being chosen.Footnote 5 I show that pluralism at the level of logical systems requires a certain monism at the level of meta-logic, and so, in a sense, there cannot be pluralism all the way down. This is not just the claim that there must be some unifying feature to all of the logics that qualifies them as being pluralistic tokens of a monistic type. Of course, to be pluralist about x, the different x1…xn need to be a kind of x, giving an uninteresting case of how pluralism bottoms out in monism regarding what the pluralist is a pluralist about. So, I am not simply stating that pluralism about logical systems bottoms out in monism about logic just due to the logical systems having a shared subject matter of logic. Instead, I argue that adequate logical systems bottom out in shared meta-logical content, and as such logical pluralism is limited. The pluralism is limited at the level of logic due to the requirements at the level of meta-logic, and the plurality of adequate alternative logical systems is limited to those that share a certain meta-logic.

I use the term ‘meta-logic’ to pick out a meta-level M of rules that underwrite the rules of inference at the level of a logical system L. Standardly (yet disputed), M is taken to contain analogues of all the rules of L, such that the meta-language of M has the same logic as the object-language of L.Footnote 6 But I argue that for every adequate L, M must include analogues of the following basic logical rules of inference: Modus Ponens (hereon MP); and Universal Instantiation (hereon UI). I argue that there is something special about MP and UI that give them this privileged status at the meta-level. I will demonstrate what I take this special feature to be through an examination of their vulnerability to Kripke and Padró’s ‘adoption problem’, which argues (against Carnapian logical pluralism) that adopting any logic is impossible:

… the Carnapian tradition about logic maintained that one can adopt any kind of laws for the logical connectives that one pleases. This is a principle of tolerance… Now, here we already have the notion of adopting a logic… As I said [last time], I don’t think you can adopt a logic.Footnote 7

Somewhere between the Carnapian and Kripkean extremes, I argue that there can only be alternative logical systems up to a point, but we cannot do (or have) logic without UI and MP—this is the limit to logical pluralism. For the same reason that UI and MP are unadoptable, they are also basic and required at the meta-level M.

2 The adoption problem

In order to see what I see is special about MP and UI, we must take a (de)tour via Kripke and Padró’s adoption problem (hereon AP), which can be outlined as such:

Certain basic logical principles cannot be adopted, because, if a subject already infers in accordance with them, no adoption is needed, and if the subject does not infer in accordance with them, no adoption is possible.Footnote 8

Utilizing the AP, I show that there are only some logical rules that cannot be adopted, in that they cannot be rationally accepted and utilized to guide inferences. I argue that these rules are the most basic of our logical rules, and the reason why they cannot be adopted is due to them being what I diagnose as ‘self-governing’. I describe a rule as being self-governing when it is of the very structure that it itself governs, which results in it presupposing and applying to itself. The only rules that I consider as self-governing in this way are UI and MP. On my analysis, the reason why such rules cannot be adopted is the same reason why I take those rules to be basic and required at the meta-level for any adequate alternative logical system: namely, because they govern all logical rules of inference, including themselves.

To demonstrate the self-governance of UI and MP and the relevance of this to logical pluralism, I will first need to dissect the AP as follows. In Sect. 2.1, I will describe the type of subject who would be directly affected by the AP—namely those who lack the relevant practice of inferring in a certain way. In Sect. 2.2, I will clarify the notion of adoption and what exactly in the process of adoption causes difficulties for such a subject—namely when it comes to inferring in accordance with the rule in virtue of accepting that rule. In Sect. 2.3, most of the exegesis stops and my analysis begins, as I will discuss which logical rules I take to be affected and what it is about them that makes them unadoptable—namely the most basic rules of inference, UI and MP. Then, in Sect. 3, I will show that such basic rules encounter a kind of self-governance by being of the very structure that the rule itself aims to govern, and it is this feature that I argue prevents them from being adoptable. As such, I use the AP to manifest the self-governing nature of the basic logical rules of inference. I dissect the problem with adoption by clarifying the problematic adopter (the type of subject), adoption (the part of the process), and adopted (the rules affected), and I use this to provide my own account for what it is that makes a logical rule basic: by being self-governing. Finally, in Sect. 4, I argue that these basic rules provide the necessary meta-logic for all adequate logics, as all logical rules (including UI and MP) will presuppose them.

2.1 The adopter

The AP is best described with an example. So let me introduce Padró’s case of Harry and Kripke’s situation of John the raven.Footnote 9 Harry is what I describe as a ‘novice’, where to be a novice is to have no experience of a certain thing, in this case with the rule of inference called Universal Instantiation (UI). UI tells us that from any universal statement each particular instance follows. Harry is a UI novice because he has never heard of, nor inferred in accordance with, the UI rule, and so he has no familiarity with either the rule or the practice. The AP arises when we invite such a novice to pick up the practice of inferring according to a specific rule of inference, by means of accepting that rule itself. So suppose we want Harry to adopt the UI rule, so that he can use it to infer the colour of John, a particular raven that he cannot see, from the universal statement that the colour of all ravens are black. Kripke and Padró claim that telling Harry the UI rule would not help him make the inference about John’s colour.Footnote 10 Harry would already need to be able to make UI inferences to grasp that the UI rule applies to the case of ravens, namely to the universal statement about their colour. Yet Harry cannot apply it to this case of ravens, since to do so presupposes a move from a general rule to a particular case—a move that Harry has never performed. In a sense, Harry’s ‘novice’ status paralyses him, since without the corresponding inferential practice in place (or as I take it, UI in the meta-logic), Harry cannot know how or when to apply the rule.

Given this set up, a worry is whether such novices who cannot adopt certain rules are even possible: it may be the case that we are not like Harry, and also it may be that there never has been and never will be anyone quite like Harry. Without any such novice subjects though, there would be nobody for the AP to directly apply to. But such an objection seems to miss the point. Harry’s novice status highlights that the inferential practice is prior to the acceptance of the inference rule, and this tells us something general that applies to us all. Regardless of their reality, considering novices like Harry provides us with counterexamples to accounts of rule-following and the nature of inference (specifically, accounts that require a prior acceptance of the rule and that give such rules a guiding role). Therefore the worry is not whether we could be in Harry’s position or whether such novices exist, but what hypothesizing about such novices will tell us about the possibility of rule-following and the nature of inference, and of greater interest here, the limits of logical pluralism. I will argue that the difficulty Harry faces due to being a novice shows us something significant about the inference rules that he tries and fails to adopt. Harry’s novice status serves to bring out a feature of those rules that I will call ‘self-governing’, which on my analysis is what prevents them from being used on the basis of rational acceptance only. Next I will clarify what I take to be the most important element of adoption to understand what in the process is so problematic.

2.2 The adoption

Padró characterizes the notion of adoption as such:

Adoption of a logical rule = acceptance of the rule + practice of inferring in accordance with that rule in virtue of the acceptance of that rule.Footnote 11

So, to adopt a rule is to come to infer in accordance with it because one accepts it. Under this characterization, there cannot be any use-less adoption. The practice of inferring is a necessary part of the adoption process; it is built into the notion of adoption by definition. If you accept a rule but fail to infer in accordance with it as a result, then you fail to adopt the rule. Thus ‘acceptance’ is not ‘adoption’. So adoption is useful or impossible, (where to be useful is to generate the practice), and Padró and Kripke aim to show that it cannot be useful and so it’s impossible.Footnote 12 With adoption defined, we can identify three elements of the adoption process:

(A) The acceptance of an inference rule R

(B) The practice of inferring in accordance with that rule R

(C) Doing B in virtue of A

In order to successfully adopt, ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’ need to occur, as their combination is simply what adoption is by definition. Kripke and Padró argue that Harry fails to adopt, and so Harry must be failing to do at least ‘A’, ‘B’, or ‘C’, but which is it?

Let’s start with ‘A’. Padró equates acceptance with belief: “acceptance of the rule [is] understood as an explicit or implicit belief that the rule is correct.”Footnote 13 I, however, take acceptance to be identified with only explicit belief since implicit belief may be taken as a disposition to act in a certain way that blurs the distinction between ‘A’ and ‘B’ (and we should keep them distinct). It is built into the example of Harry that he does explicitly believe and accept UI, as Kripke describes the case: “I say to [Harry], ‘consider the hypothesis that from each universal statement, each instance follows’, and he believes me.”Footnote 14 At this point then it cannot be failure of acceptance of a rule that makes adoption impossible, as the AP is set up on the assumption that belief, and thus acceptance, occurs in Harry’s case.

So, moving on to ‘B’. Whether the practice of inferring in accordance with a rule is problematic depends on how we interpret the ‘in accordance with’ notion: as either conformity or rule-following.Footnote 15 Harry may accidently conform to UI by uttering ‘All ravens are black, therefore John the raven is black’, as a sequence of words or thoughts can happen to conform to a rule. If such conformity were all that is required for inferring in accordance with a rule, then Harry would be said to infer in that scenario. Inferring would be simply the movement from one thought to another, as it is easy enough to conjure up a rule that it conforms to.Footnote 16 But an issue that the AP forces upon us is whether inferring is conforming, or, on the other hand, if it is a case of rule-following. If inferring is a rule-governed practice, then the distinction between ‘B’ and ‘C’ is blurred (which we should keep sharp), as the practice occurring in ‘B’ is already in virtue of the rule at hand. The ‘in accordance with’ in ‘B’ needs to be interpreted in a non-rule-guided way, as otherwise ‘in accordance with’ in ‘B’ seems to do the same work as ‘in virtue of’ in ‘C’ (as it is natural, though contestable, that rule-following consists of ‘B’ in virtue of ‘A’). Such a conflation would prevent us from locating the specific problem in adoption.

Part ‘C’ of the process ensures that ‘A’ is prior to ‘B’, since ‘C’ demands that the practice in ‘B’ is developed in virtue of the acceptance in ‘A’, where the acceptance comes before the practice. It is this requirement from ‘C’ that makes the practice of inferring a rule-governed process, which begins in and is explained by acceptance of a rule of inference. ‘C’ is a relation between ‘A’ and ‘B’, namely, doing ‘B’ in virtue of ‘A’. I call this ‘in virtue of’ relation the ‘utility’ of a rule, as it intends to give the rule a use.Footnote 17 Without ‘C’ supplementing ‘B’ (or being built into ‘B’ via a loaded understanding of what it means to infer in accordance with a rule), we accord to a rule by mere conformance, and the rule plays no guiding role. What ‘C’ adds is the rule being the reason for the conformance, so that the rule is followed. Whether we can understand rule-following without ‘C’, and inferring without rule-following, is what the AP invites us to explore.Footnote 18If it is ‘C’ that transforms the inferring in ‘B’ from accidental conforming to guided rule-following, then the AP challenges the possibility of rule-following, and if the inferring in ‘B’ cannot be understood as rule-following, then the AP challenges the nature of inferring. This specifies Padró’s target of the AP as accounts of rule-following and inference where rules have utility.

But why is it that rules cannot play a guiding role? This is where Kripke and Padró’s analysis ends, and mine really takes off. My explanation for the lack of utility in the rules is due to the nature of the rules in question. On my analysis, there is something special about such rules that make them unadoptable, as there is a feature of them that requires one not to be a novice precisely in order to be able to adopt them. This special feature is the topic of the next sections and provides the reason why such rules are needed at the meta-level of all adequate logical systems.

2.3 The adopted

Kripke argues that in general, logic cannot be adopted. Yet, in Padró’s articulation of the AP she restricts the unadoptable rules to only some basic ones, as such:

The adoption problem is only supposed to affect some basic logical principles or rules, like Universal Instantiation or Modus Ponens… Kripke mentions two other principles as being affected… adjunction and non-contradiction (the list, however, wasn’t intended to be exhaustive).Footnote 19

The rules that I, like Padró,Footnote 20 will focus on are MP and UI. Padró thinks that the AP “would be interesting even if it only worked with MP and UI”,Footnote 21 and so she clearly allows the AP to have limited scope. Padró does not say much about the similarity between MP and UI, yet claims that “there is something special about these [unadoptable] principles: they have a self-supporting character that appears to run deep.”Footnote 22 Kripke also claims that there is something unique about these rules, but Kripke and Padró are “a bit more cautious and reserve judgment on the matter of uniqueness”.Footnote 23 I (with less caution) attempt to fill in these gaps in the analysis, and provide a fuller account of what it is that qualifies rules as being basic that prevents them from being adopted and requires them in the meta-logic of adequate systems.

Others describe what makes a rule basic is them being ‘underived’, ‘fundamental’, ‘primitive’, ‘unjustified’ (as we will discuss in more detail later in Sect. 3.4) or even ‘blind’ when it comes to the following of such rules.Footnote 24 Boghossian also exercises caution when it comes to answering the question as to what makes rules basic or the following of them blind (without intentional or explicit acceptance):

You want to know which inference patterns are permitted to be blind? These ones: Modus Ponens, Non-Contradiction, and a few others. Don’t ask why it is precisely these inference patterns that are sanctioned. There is no deep answer to that question; there is just the list.Footnote 25

I disagree that there is just a list, as I argue there is something the entries on the list have in common, which provides a ‘deep answer’ to the question of what counts as being a basic logical rule of inference: namely, they are self-supporting due to exhibiting what I call self-governance.Footnote 26 These rules govern such basic and fundamental patterns of inference that they underwrite the application of any logical rule, including themselves. As such, they govern their own application. It is in virtue of these basic rules being self-governing that they cannot be utilized or adopted, and thus I diagnose the AP as being due to self-governance. I will give my own analysis by looking at the general structure of all logical rules of inference, to demonstrate how such structure presupposes (and thus requires) both MP and UI.

3 Self-governance

3.1 General structure of rules

Logical rules of inference are, very generally speaking, universal and conditional in their structure. To be of a universal structure is to apply in all cases of a certain kind. To be conditional in structure is to say what to do if one is in a case of a certain kind. Logical rules of inference take us from premises to a conclusion via a conditional, and are universal meaning that they apply in all cases when the antecedent of that conditional is satisfied.Footnote 27 The antecedent of the conditional will name a situation when the rule is applicable, and the consequent of the conditional will name what one should do when faced with an instance of that situation. It is therefore written in to the very nature of what it is to be a logical rule of inference that it is universal and conditional in its structure. I thus take the general structure (GS) of logical rules of inference to be universal and conditional, so that all logical rules are of the structure GS, which I formulate (somewhat crudely) as follows:

(GS) If the premises are an instance of structure X then infer conclusion Y.

Roughly, GS describes how logical rules of inference are universal (by applying in all cases of structure X) and conditional (by moving from X to conclusion Y).

The truth of GS is not easy to prove, however it does find support in the literature. For example, Boghossian similarly notes that logical rules have “general content” and “conditional content” by telling us “to always perform some action, if I am in a particular kind of circumstance.”Footnote 28 This can easily be rewritten as equivalent to GS, where the ‘particular kind of circumstance’ is ‘structure X’ and ‘some action’ is ‘conclusion Y’. Furthermore, Boghossian states that inferring is “both general and productive”Footnote 29 where the ‘general’ here indicates what I call being ‘universal’ and the ‘productive’ indicates what I call being ‘conditional’. Boghossian also notes Kripke’s preferred construal of rules as being general imperatives of this form:

‘If C, do A!’ where ‘C’ names a type of situation and ‘A’ a type of action. On this construal, rules are general contents that prescribe certain types of behavior under certain kinds of condition.Footnote 30

This again has similarities to GS, where ‘C’ names a type of situation by describing its structure X, and ‘A’ is the action of inferring conclusion Y. Once more, we see what I call the universal and conditional structures being alluded to in ‘If C, do A!’.

GS is also similar to Wright’s ‘Modus Ponens Model’ of rule-following where we are presented with a conditional rule, a premise about the situation we are in satisfying the antecedent of the rule, and then a conclusion about what we infer when we apply the rule to that situation, giving us the consequent of the rule:

The rule is stated in the form of a general conditional. A minor premise states that, in the circumstances in question, the condition articulated in the antecedent of the rule is met. The conclusion derives the mandate, prohibition, or permission concerned.Footnote 31

To reframe this according to GS, we need only see the ‘minor premise’ as ‘structure X’, and ‘the conclusion’ as ‘conclusion Y’, such that the rule’s ‘form of a general conditional’ is articulated by GS. Despite the similarities, Wright’s ‘Modus Ponens Model’ and my GS are different since GS applies to the rule that is embedded into the first step of Wright’s model, and articulates that rule as being broken up into the antecedent (‘structure X’) and the consequent (‘conclusion Y’). I take GS to be the general structure of the logical rules themselves, whereas Wright’s model is the general structure of rule-following. And as I aim to show, simply accepting the rule is not enough to follow it, as one must also know how and where the rule applies, by seeing that the antecedent is satisfied and by having the practice already in place to apply the rule to that case.

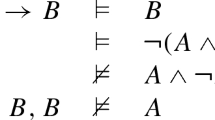

3.2 Modus Ponens and Universal Instantiation

MP tells us: when faced with a conditional and its antecedent (structure X), infer the consequent (conclusion Y). UI tells us: when faced with a universal (structure X), infer an instance (conclusion Y). MP is a rule that governs conditionals; UI is a rule that governs universals. But MP and UI are conditionals and universals themselves, in virtue of all logical rules being of conditional and universal structure, as GS shows.Footnote 32 So given that all logical rules of inference are of the form GS, which is itself a universal and conditional, then those rules that govern or describe how to deal with universal or conditional structures will face problems by being of the structure that they themselves govern. Thus UI and MP will unavoidably govern themselves, due to always being logical rules which have the structure given by GS, which is the same as the structure X that they themselves govern. On my analysis, it is self-governance that prevents a logical rule from being adoptable, and (as I will argue) explains its necessary inclusion as a basic logical rule of inference at the meta-level of any adequate logical system.

We find further support for my claims when we look at the related cases of Harry and Lewis Carroll’s TortoiseFootnote 33 who battle with UI and MP respectively. I claim that both their problems arise due to those rules being self-governing. As for Harry, he cannot infer the colour of the particular raven by being told the colour of all ravens and the UI rule, since he cannot apply UI to the case of ravens. Harry cannot infer that the universal statement about all ravens is one that the UI rule applies to, as that presupposes that he can infer from the universal rule of UI to the particular universal about ravens. This is due to UI itself being of universal form, and as such being of the structure X that it governs. Since Harry does not know what to do in a case of structure X, giving him a rule that governs structure X that is itself in the form of structure X is not going to help him. He does not infer instances from universals, and so will not infer from the applicability of the universal rule UI to the instance of the particular universal case of the ravens. He needs to apply UI to the case in order to then apply it in the case, and as such needs to apply it twice to infer the colour of that raven. This is why UI is required in the meta-logic and the practice needs to be prior to acceptance, as otherwise UI is impossible to utilize. As for Carroll’s Tortoise, she refuses to accept that the sides of the triangle are ‘equal to each other’ when they are ‘equal to the same’, having been told that if the sides are equal to the same then they are equal to each other, and being told the MP rule which she challenges. I claim that this is due to MP being of conditional form—the very form that the Tortoise refuses to infer in accordance with. Since she does not respond to structure X, giving her a rule that dictates how to respond to X that is itself in the form of X is not going to move her to infer. These self-governing rules are, as Kripke says, “completely useless”Footnote 34 for getting someone to infer, due to such rules presupposing themselves which makes them unadoptable. If UI and MP are not present at the meta-level then, no rule of inference in any logical system can be adopted, which leads to a significant limitation to logical pluralism.

One might object that UI and MP do not have to be stated as generalizations or conditionals. But I take it that the specific formulation of UI and MP makes no difference to their self-governance and thus their status as being unadoptable. Padró likewise argues “variations as to how to construe these rules won’t affect the argument.”Footnote 35 So the AP holds for such logical rules regardless of how they are stated. It does not matter how exactly UI and MP are formulated, as they will still be logical rules of inference and as such will still have the general form of such rules as shown by GS which utilize both a universal and conditional structure. UI need not be explicitly formulated using a universal, as the problem is that the rule (like all logical rules) is general. Thus UI will apply to all cases of universals, making it self-governing, even when it is not referred to explicitly. Likewise, MP need not be explicitly formulated using a conditional, as the problem arises that the rule (like all logical rules) is conditional. MP, like all other logical rules, features a conclusion that is detached and in need of being arrived at through an inference which will itself be of a conditional structure. Therefore, UI and MP will always be of the structure X that they themselves govern due to GS. Regardless of how UI and MP are specifically formulated, it is just due to the fact that they are rules that have the general structure of being universal and conditional (like all rules do), that they self-govern by governing how to deal with universal or conditional contents.

We also cannot prevent UI and MP from being self-governing by taking a syntactic statement of the rules using logically equivalent componentsFootnote 36 to avoid making use of ∀ or →. They then won’t explicitly refer to the logical component they govern, but still cannot help but be of the structure that they govern, and so will be self-governing and unadoptable. For example, we may state MP as: from P&(P → Q) infer Q.Footnote 37 If we rewrite this so that it does not make use of the conditional P → Q and formulate it with a logically equivalent ~ (P&~Q), we get: from P&(~(P&~Q)), infer Q. Yet this would still be unadoptable since its application still involves the use of an MP inference.Footnote 38 A subject still needs to understand that the antecedent situation P&(~(P&~Q)) holds and that when it holds they should infer Q. Rewriting MP without the conditional does not make it adoptable.

Likewise with UI, which we may understand as: from ∀xFx, infer Fa. This may be rewritten without explicit reference to the universal ∀x and instead using a logically equivalent ~ (∃x) ~ to create this rule: from ~ (∃x) ~ Fx, infer Fa. This would still be unadoptable, just like in its original formulation, due to being self-governing as its application involves the use of an UI inference pattern. A subject would still need to somehow understand that a particular instance of the antecedent situation ~ (∃x) ~ Fx holds and that whenever there is such an instance they should infer Fa.Footnote 39 This is because, regardless of the rule in question, one needs a grasp of how to deal with universals and conditionals due to GS showing us that all rules are of universal and conditional structure. So, however we formulate UI and MP, they always presuppose an understanding of, or inference in accordance with, UI and MP, due to GS. UI and MP will always be unadoptable because of this, and will always be basic rules required at the meta-level in order to understand rules at the level of logical systems. UI and MP needn’t be stated in any particular way, they just need to be logical rules that govern universal and conditional structures.

3.3 Adjunction and the law of non-contradiction

Kripke and Padró claimed that adjunction (AD) and the law of non-contradiction (LNC) were also potential candidates for being unadoptable, and Boghossian took LNC to be basic and followed blindly. As we will see, Priest also takes there to be something special about AD. We will look at LNC first, and then at AD. (Note that analyzing LNC in terms of my GS is a bit more complicated, as LNC is not strictly a rule of inference.) Anyway, this is Padró’s argument for LNC’s unadoptability:

If we try to get someone who doesn’t reason in accordance with it to adopt it, the problem is that the subject could hold the law of non-contradiction itself to be both true and false.Footnote 40

But this strikes me not as unadoptable in the way that we have been describing, but more like a paradox, that in taking LNC to be true and false it ends up only being false. One simply could not accept LNC and its negation, for to do so would be self-defeating if LNC is true. But this has nothing to do with adoptability or basicness. Here, the problem with LNC does not derive from the ‘in virtue of’ relation, as one could keep their practice of inferring in accordance with LNC in virtue of accepting it, even when they also accepted its negation. One could demonstrate acceptance of LNC by inferring according to reductio ad absurdum (RAA), where one can reject an assumption in light of a derived contradiction (to show a rejection of the contradiction, and thus an acceptance of LNC). But RAA seems to be adoptable, since GS is not of the form of a reductio, and one needn’t already have experience of denying assumptions in light of contradictions in order to practice RAA, nor is RAA needed at the meta-level. As long as some of our practice includes rejecting contradictions due to taking LNC as true, LNC is adoptable. LNC may have special traits, but being unadoptable and basic is a specific trait that I classify as being self-governing, which LNC does not exhibit. Therefore LNC is not a required rule for adequate logical systems, thus it need not feature at the meta-level and logical pluralism is not limited by it.

Now let us turn to the rule AD. Priest claims that AD is always valid:

I think it just false that all principles of inference fail in some situation. For example, any situation in which a conjunction holds, the conjuncts hold, simply in virtue of the meaning of ∧.Footnote 41

So, does this show us something special about AD regarding its basicness, unadoptability and required inclusion at a meta-level of adequate logical systems? Let us look to its structure for answers. The structure X that AD governs is of two separate conjuncts coming together as one, introducing the logical component ‘and’ to conjoin them. Not all logical rules contain separate conjuncts (as they do not all contain multiple premises), and so GS is not itself of the structure of a conjunction (as conjunction is not part of the general structure of all of the logical rules). So, AD will not be self-governing in virtue of GS being of the structure X that AD governs. However, one may argue that AD is self-governing because structure X is described using the logical component that X governs. If the AD rule were stated as ‘If ‘P’ and ‘Q’ then infer ‘P&Q’’, then the antecedent explicitly refers to the logical component, ‘and’, that AD governs. As Padró describes:

If we accept that ‘P’ is true and accept that ‘Q’ is true, then adjunction is needed to conclude that one has accepted that ‘P is true and Q is true’.Footnote 42

This means that whenever there is more than one premise to an argument, in order to conjoin them as a singularity one will need to list them as a plurality to take each as true. But this method presupposes AD as it requires us to be able to individuate multiple premises, thus all multi-premise inferences would presuppose an inference according to, AD. Importantly, MP is a multi-premise inference pattern, since one uses it to infer from a situation of P and P → Q to a conclusion Q. Yet we have argued that MP is unadoptable due to being presupposed by GS. So if GS presupposes MP and MP presupposes AD, then GS presupposes AD. Furthermore, AD itself is a multi-premise inference pattern, and so AD presupposes itself, thus it seems to have the self-governing feature that prevents it from being adoptable.

Yet I do not agree with Padró that AD is unadoptable. This is because, on my analysis, what generates unadoptability is the general structure of logical rules (GS) being itself of the structure that the rule governs (structure X), and since GS is not itself a conjunction then AD need not be a conjunction itself. On a classical framework, all multi-premise rules can be reformulated as a single-premise rule, conjoining the premises with something that is logically equivalent to P&Q, such as ~ (~Pv~Q). Therefore, AD can be rewritten with one premise, moving from ~ (~Pv~Q) to the conclusion P&Q (rather than from two premises, P, and Q). This shows that it is not necessary for any logical rule to presuppose AD, as adjunction is not required when all inferences can be understood using a single premise by conjoining multiple premises with logically equivalent terms. MP, AD, and all other multi-premise rules need not presuppose AD since they can bypass the need for adjunction by rewriting into a singular premise, which at least on a classical framework is done via interdefinability. This emphasizes the importance of GS, since it is this that cannot be avoided. We can rewrite rules in ways that avoid explicit reference to the components they govern, but we cannot avoid that they are rules, and so we cannot avoid that they are universal and conditional in structure due to being general and having a detached conclusion, as shown by GS. But since logical rules are not always of the structure of adjunction, on my analysis AD is not self-governing in the required way to be unadoptable or needed at the meta-level.Footnote 43

3.4 Justification and basicness

The self-governing nature of MP and UI is not only problematic for adoption of those rules, but also for justification of those rules. The problem of justifying a logical rule by means of the very same rule is called ‘Rule-Circularity’ in the literature.Footnote 44 The problem of Rule-Circularity is roughly that the justification of any logical rule will have to appeal to the basic logical rules, and so the justification of the basic logical rules will appeal to themselves. They will do this by taking one step in their justification that makes use of a basic logical rule. Naturally, if the basic logical rules already appeal to themselves in their formulation, then they will appeal to themselves for justification, just as they do in application. This circularity, which I take to be caused by self-governance, is particularly clear in the case of MP when attempting to justify it syntactically, as Boghossian describes:

It is tempting to suppose that we can give an a priori justification for MP on the basis of our knowledge of the truth-table for ‘if, then’. Suppose that p is true and that ‘if p, then q’ is also true. By the truth-table for ‘if, then’, if p is true and if ‘if p, then q’ is true, then q is true. So q must be true, too. As is clear, however, this justification for MP must itself take at least one step in accord with MP.Footnote 45

The AP therefore seems to be just another manifestation of this Rule-Circularity problem, both problems being caused by the self-governance of some logical rules. Yet what the AP shows us is that Rule-Circularity arises at a more fundamental level than justification, and what my analysis shows us is that at each level this is due to self-governance. So not only can we not justify MP and UI unless by means of themselves but we also cannot utilize them, due to their self-governing nature.

So far then I have argued that for a logical rule to be unadoptable is for it to be self-governing due to the general structure of logical rules presupposing the rule in question. I have shown the connection between the AP and Rule-Circularity, in that self-governance causes not only problems for the utility but also the justification of logical rules of inference. But since the AP and Rule-Circularity are put forward as affecting only the basic rules, I now suggest that my analysis provides an understanding of what basicness is, what causes it, and what it causes.

UI and MP are self-governing in that all logical rules are of conditional and universal structure, such that they unavoidably presuppose an understanding of UI and MP. Therefore, all logical rules require one to already know how and when to apply UI and MP, and this is what makes UI and MP basic, since all other logical rules presuppose them. Many describe ‘basic’ as meaning ‘underived’. If all other rules ‘derive’ from the basic rules, then any problem with the basic rules impacts on the other rules. This is due to the basic rules being essential for what a logical rule is, so that if a novice cannot grasp basic rules then they cannot grasp logical rules at all. It thus seems the non-basic rules are not derived from UI and MP, but rather they are governed by UI and MP. This is in line with a passing comment from Kripke about basicness that captures my analysis of the AP, as Padró notes:

Maybe this is what Kripke has in mind when he says that sometimes the more basic principles are ‘built into’ the other ones in a disguised way.Footnote 46

I develop Kripke’s passing comment by arguing that UI and MP are built into the other rules due to self-governance, in virtue of the general structure of all logical rules being both universal and conditional. Logical rules seem to presuppose that we can make sense of instructions of the form ‘if…then’, and recognise instances as instances of general forms. Therefore a grasp of UI and MP is central to the notion of a logical rule of inference, and that is what makes them basic, unadoptable, and required at the meta-level for any adequate logical system. Without UI and MP, there is no way to make sense of, or apply, any other logical rules, since all of the logical rules depend on UI and MP to govern them. If we do not have UI and MP at the meta-level, then we will not have the instruction or guidance to move from a universal rule to a particular instance of structure X, nor to derive conclusion Y if in an instance of structure X. This is why UI and MP are basic! Without them in the meta-logic, the logical systems and their rules are useless, and thus, inadequate.

4 Implications for logical pluralism

Logical pluralism, in particular from the Carnapian tradition, requires there to be multiple true logical systems that are equally worthy of being chosen. What I have argued is that the worthy systems are limited to those that abide by a meta-logic which contains analogues of UI and MP, otherwise the system is inadequate. This is because whatever rules you have at the level of logical systems, for any logical system, one will require UI and MP at the meta-level to govern those rules. A meta-logic without UI and MP will itself be inadequate to play the role that meta-logics are required to play for logical systems. As such, adequate logical systems are limited to those with adequate meta-logics, where the meta-logics must include UI and MP. Thus logical pluralism is limited, as I provide an extra constraint on the logical systems that are worthy of being chosen via constraining the meta-logic. The appeal to logical systems to motivate pluralism is, Kripke says, ‘misleading’:

What has given people the very misleading impression that there can be alternative logics in the same way there are alternative geometries is the existence of alternative formal systems. You see, one might think, ‘Look, logic’s got to be different from geometry, because we need to use logic to draw conclusions from any hypothesis whatsoever.’ Well, now, this is supposed to have been answered with the notion of a formal system. Formal systems can be followed blindly; a machine can check the proof; you don’t have to do anything at all; etcetera, etcetera… Nothing is more erroneous. Of course, a machine can be programmed to check the proof. … But anyway, we are not machines in the sense of not using reasoning to understand what we are told, what formal system this is. We are given a set of directions, that is, any statement of the following form is an axiom: if these premises are accepted any conclusion of this form must be accepted. These directions themselves use logical particles, as Quine has rightly pointed out. Because of this use of logical particles, understanding what follows in a certain formal system itself presupposes a certain understanding of logic in advance, and cannot be done blindly.Footnote 47

What this suggests, as I have argued and demonstrated, is that appealing to the alternative logical systems that logical pluralism permits does not escape a certain monism at the meta-level of logic. UI and MP are presupposed in understanding what those formal systems entail and how the rules from those systems can be understood. Without UI and MP, we cannot derive anything from our plurality of logical systems, or even comprehend the rules of inference at play in those systems. We cannot use the existence of multiple alternative logical systems and their practical usage in various domains to prove the truth of logical pluralism, since beneath those systems there is a fundamental meta-logic that is required to make sense of them. This is further supported by the following quote from Kripke:

There is no bedrock in the notion of a formal system which we can choose somehow to adopt or reject at will and then tailor one’s logic to it. One has to first use reasoning in order to even see what is provable in a formal system. Formal systems don’t say anything as they are; they are just formal objects… If one then gives them an interpretation, one can check, using the reasoning that we always did (and what other reasoning do we have? None, as I’m trying to say) whether under this interpretation they are (a) sound and (b) complete.Footnote 48

It is this sort of argument that is often cited to motivate the dis-analogy between logic and geometry. Geometry (like formal logical systems) depends upon a certain logic in order to derive anything from it. But there is no place else to go when deriving things from logic itself, and it cannot be done independently of itself.Footnote 49 Logic is needed to reason about anything, including formal logical systems and geometry.Footnote 50 In logic we say that a meta-logic is required (whereas for geometry no meta-geometry is required), and what I have argued is that this meta-logic must include UI and MP given their importance in underwriting the nature of what logical rules of inference are, what they do, and how they work. Even those who defend the analogy between logic and geometry, like Priest, appreciate this idea:

The articulation of a logical system requires the employment of a metalogic (normally an informal one, and not necessarily classical), whereas the articulation of a geometric system does not require the employment of a metageometry.Footnote 51

I conclude that logical pluralism is limited due to the required employment of UI and MP in the meta-logic, which itself is due to the self-governing nature of UI and MP. I develop, rather than repeat, ideas from the AP and Kripke, by restricting the AP to UI and MP, diagnosing self-governance, formulating GS, defining basicness, and most importantly in this paper, explicitly relating to limiting logical pluralism.

5 Conclusion

The morals that one can draw from this paper are: Logical novices cannot adopt basic logical rules. Why? Because they are not able to utilize such rules, in that they are not able to infer in accordance with them in virtue of accepting them. Why? Because such inference presupposes the very same rule they are accepting. Why? Because basic logical rules are self-governing as they are of the structure of the logical component that they themselves govern. What does this mean for logical pluralism? It shows logical pluralism is limited, given that these basic logical rules underwrite all the other rules, meaning they will be required at the meta-level for any adequate logical system. This leaves us with a kind of monism (or at least another restricted pluralismFootnote 52) at the meta-level, given that we cannot escape the meta-logic that we use to reason about (and derive things from) logical systems. Furthermore, the content of that required meta-logic must include UI and MP, as the reason why UI and MP are unadoptable is the same reason why they are basic and presupposed at the meta-level—namely, self-governance.

Notes

Carnap (1937), pp. 51–52.

Carnap (1937), p. xv.

Beall and Restall (2000), p. 475. ‘Logic’ (capital L) for the discipline; ‘logic’ for a system.

I do not use the term ‘adequacy’ for the conjunction of the soundness and completeness of a system (yet perhaps the limits I highlight pertain to meta-logical adequacy in this sense).

One might argue that I am making an epistemological argument against a metaphysical thesis of logical pluralism. I thank a reviewer for this. But in so far as, say, Carroll’s (1895) problem reveals an important constraint on logic despite its epistemological flavour, so can my argument here be taken to reveal an important limitation on logical pluralism, be it epistemic or not. My result can also be seen as meta-meta-logical, given that the adequacy of a logical system depends on certain constraints on the meta-logic behind it.

Kripke [Princeton Seminar, quote found in Padró (2015), p. 113].

Padró (2015), p. 42. Padró speaks of logical principles here but she and Kripke argue that the adoption problem holds also for logical rules of inference. I will only speak of logical rules, but I take what I say in this paper to apply straightforwardly to logical principles. I also do not enter into the debate regarding the distinction between rules of inference and rules that state what follows from what—for a discussion of this, see Harman (1986).

See Padró (2015). Harry is, of course, fictional, as is John the raven.

Kripke and Padró state that someone who sometimes but not always infers according to UI may be helped by stating the rule for them. This shows the significance of novice status.

Padró (2015), p. 32. To make sense, adoption, acceptance, and practice, must be distinct.

It should be emphasized that Padró’s ‘adoption’ is a technical term, where others may use the word differently in a less technical way in the literature. Indeed, Kripke complains that noone in the literature explains what they mean by ‘adoption’, yet it is used as if there were a standard procedure that adoption consisted in. One should be careful when engaging in this AP to ensure that they are talking of the same kind of ‘adoption’. Even Kripke has used the word in a way that is incompatible with Padró’s definition: “if we did adopt [a rule], it would have done us absolutely no good.” (Quote found in Padró (2015), p. 112). To do ‘no good’ is to be useless, and so Kripke must mean that the acceptance does ‘no good’. Kripke does not define what he takes adoption to be, since he complains that he simply does not understand what it could mean. (See Padró (2015), fn. 42, p. 31). Yet Padró’s characterization is meant to capture the way Kripke uses the word, so I work only with Padró’s definition.

Padró (2015), p. 190. Adoption is considered only from the first person perspective.

Quote found in Padró (2015), p. 35. Padró (2015), p. 62 says acceptance may be problematic: “It could be argued that neither Harry nor [the Tortoise] have either accepted or understood the rules we gave them.” This was first raised in connection with Carroll by Black (1970), p. 21: “The form of words ‘understanding and accepting premises of the form p and if p then q, but not accepting the corresponding position of the form q’ describes nothing at all.” Padró thinks Black is correct but misses the point: in this situation, the AP repeats itself, as the reason why Harry could not accept is the same reason why he could not adopt. I argue this demonstrates something special about the logical rules UI and MP.

The distinction is widely debated in the literature. See Miller and Wright (2002).

Boghossian (2008), p. 9 notes there are infinitely many rules that our behaviour accords to.

This ‘in virtue of’ relation (utility of a rule in ‘C’) is similar to what Kripke (1982) calls ‘internalizing’ a rule, and is captured by Boghossian’s ‘Taking Condition’ (2014, p. 4) which specifies the relation between a conclusion and the premises we take it to follow from, and it distinguishes inferences from mere sequences of thoughts. What all these notions refer to is the act of inferring being done because of the rule. But this is not a causal connection, as Padró (2015), p. 42 describes. Rather it treats the rule as being the reason for the inference due to the rule guiding the inference, and can be said to ground it in some way.

Padró (2015), fn. 52, p. 37. Padró says these are directly affected (private correspondance).

Padró (2015), fn. 52, p. 37: “I will only talk about UI and MP. The former is Kripke’s preferred example and the latter is Carroll’s own example (and also the case that is most widely discussed in the literature), but of course it would be interesting to see which other principles are directly affected by this argument. That task, however, falls outside the scope of what I set out to do.” I somewhat take on that task so as to show the limits of pluralism.

Padró (2015), fn. 52, p. 37.

Padró (2015), p. 14.

Padró (2015), fn. 63, p. 49. Emphasis in original.

See, for example, Boghossian (2000).

Boghossian and Williamson (2003), p. 239.

I thank Conor McHugh (private correspondence) for suggesting this terminology to me.

This will not cover inferences where there are no premises and only a conclusion.

Boghossian (2008), p. 21.

Boghossian (2014), p. 12.

Boghossian (2008), p. 475. It is, however, beyond the scope of this paper to argue whether rules should be of imperative form or put in normative, permissive, or propositional terms.

Wright (2007), p. 490.

I take GS to be a conditional of the sort that MP governs. MP usually applies to material conditionals, or those rendered false by the conjunction of the antecedent and negation of the consequent. GS is not explicitly written in these terms, but since it tells us if in structure X then infer conclusion Y, we can see that it is a conditional in the required way. So, if MP both governs and is structured as a material conditional, then MP is unadoptable. All thats required is a match between what is presupposed at GS and the rule that governs it.

Carroll (1895). Harry and Tortoise are different, but they show UI and MP to be similar.

“The law of universal instantiation is completely useless… There are certain rules which you just couldn’t adopt: you couldn’t tell them to yourself, because if you told them to yourself without already using them, they would be useless; so they either don’t help you or they were superfluous anyway. UI has this character.” Quotes found in Padró (2015), p. 112.

Padró (2015), fn. 70, p. 58.

Interdefinability only holds on classical frameworks and so cannot be my method to show formulation doesn’t matter. But it is not–my method uses GS to show the form rules have.

We learn from Carroll (1895) to resist writing rules of inference for a theory as single sentences of that theory, so we ascend to the meta-language and write: ‘From P and (P → Q), infer Q’. My point is replacing P → Q with ~ (P&~Q) wont help as it only prevents MP from using a conditional in part of the rule but the whole rule will still be a conditional.

Padró (2015), fn. 56: “We could express [MP] as ((¬p∨q)∧p) → q. But again, its application will involve use of an MP inference pattern.” This is as GS presupposes MP.

Padró (2015), fn. 56, p. 43 argues: “Suppose we try to get Harry to adopt the following more complex principle: ‘if there doesn’t exist something for which a predicate F does not hold, then F holds for any particular instance.’ … It is clear that any other principle or rule we might suggest to Harry will have to be general and so their application will presuppose UI.”.

Padró (2015), fn. 52, p. 37.

Priest (2006), pp. 202–203.

Padró (2015), fn. 52, p. 37. Seemingly a grasp of meta-logical conjunction is required.

This assumes a way of identifying rules that may be contentious (but no room to discuss).

Boghossian (2000), p. 231.

Padró (2015), p. 43: “he mentions this in passing and doesn’t want to get into the issue.”.

Kripke [quote found in Padró (2015), p. 82].

Kripke [Pittsburgh Lecture, quote found in Padró (2015), p. 14].

This point is also motivated by Kripke: “Logic, even if one tried to throw intuition to the wind, cannot be like geometry, because one cannot adopt the logical laws as hypothesis and draw their consequences. You need logic in order to draw these consequences. There can be no neutral ground in which to discuss the drawing of consequences independently of logic itself. If there were it would be some special kind, called ‘ur-logic,’ and that would be what was really logic.” Kripke [Pittsburgh Lecture, quote found in Padró (2015), p. 140].

For further support of this claim, see Field (1996), p. 369, for example.

Priest (2003), p. 443.

I thank a reviewer for pointing out that my arguments for a ‘kind of monism’ at the meta-level may also be understood as arguments for a form of ‘global pluralism’ at the meta-level, as described in Haack (1978), whereby there are multiple logical systems that are compatible in the sense that they all conform to a general structure of inference. This point can be made due to noticing that GS is valid on multiple logical systems. However, my arguments aim to show that those logical systems are only adequate when their meta-level includes MP and UI, not just when GS is valid. As such, I stand by my ‘kind of monism’.

References

Beall, J., & Restall, G. (2000). Logical pluralism. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 78, 475–493.

Black, M. (1970). The justification of logical axioms. In M. Black (Ed.), Margins of precision. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Boghossian, P. (2000). Knowledge of logic. In P. Boghossian & C. Peacocke (Eds.), New essays on the a priori (pp. 229–254). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boghossian, P. (2008). Epistemic rules. Journal of Philosophy, 105(9), 472–500.

Boghossian, P. (2014). What Is inference? Philosophical Studies, 169, 1–18.

Boghossian, P., & Williamson, T. (2003). Blind reasoning. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary, 77(1), 225–248.

Carnap, R. (1937). The logical syntax of language. London: Kegan Paul.

Carroll, L. (1895). What the tortoise said to achilles. Mind, 4(14), 278–280.

Devitt, M. (manuscript). The adoption problem in logic: A Quinean picture.

Dummett, M. (1975). The justification of deduction. Proceedings of the British Academy, 59, 201–232.

Dummett, M. (1991). The logical basis of metaphysics. London: Duckworth.

Field, H. (1996). The a prioricity of logic. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 96, 359–379.

Haack, S. (1978). Philosophy of logics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harman, G. (1986). Change in view. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kripke, S. (1974a). Princeton lectures on the nature of logic. Transcription of tapes.

Kripke, S. (1974b). The question of logic. Transcription of a lecture given at the University of Pittsburg.

Kripke, S. (1982). Wittgenstein on rules and private language. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Miller, A., & Wright, C. (Eds.). (2002). Rule following and meaning. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Padró, R. (2015). What the tortoise said to Kripke: The adoption problem and the epistemology of logic. CUNY Academic Works. PhD Thesis available online. http://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/603. Accessed Feb 2016.

Priest, G. (2003). On alternative geometries, arithmetics, and logics: A tribute to Lukasiewicz. Studia Logica, 74(3), 441–468.

Priest, G. (2006). Doubt truth to be a liar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, T. (2017). Dummett on the relation between logics and metalogics. In M. Frauchiger (Ed.), Truth, meaning, justification, and reality: Themes from Dummett (pp. 153–176). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Wright, C. (2007). Rule following without reasons: Wittgenstein’s quietism and the constitutive question. Ratio, 20(4), 481–502.

Wright, C. (2014). Comment on Paul Boghossian: What is inference. Philosophical Studies, 169, 27–37.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks goes to Romina Padró, Michael Devitt, Mary Leng, Tom Stoneham, Conor McHugh, Jonathan Way, Francesco Berto, Sophie Keeling, and Ben Neeser for their very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper, and to Saul Kripke for his support of my writing this paper. Also many thanks to the audiences of the Logic and Metaphysics workshop at the City University of New York Graduate Center, the Dublin Philosophy Research Network Philosophy of Language workshop at Trinity College Dublin, the Logic as Science conference at the University of Bergen, the Research Day at the University of Southampton, and the Mind and Reason group at the University of York, where I presented ideas that derive from this paper. This paper was completed during a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, under grant agreement number 679586.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Finn, S. Limiting logical pluralism. Synthese 198 (Suppl 20), 4905–4923 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02134-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02134-8