Abstract

The conservativeness argument poses a dilemma to deflationism about truth, according to which a deflationist theory of truth must be conservative but no adequate theory of truth is conservative. The debate on the conservativeness argument has so far been framed in a specific formal setting, where theories of truth are formulated over arithmetical base theories. I will argue that the appropriate formal setting for evaluating the conservativeness argument is provided not by theories of truth over arithmetic but by those over subject matters ‘richer’ than arithmetic, such as set theory. The move to this new formal setting provides deflationists with better defence and brings a broader perspective to the debate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: the conservativeness argument

The term ‘deflationism’ is used to stand for many different views on truth by different philosophers. Perhaps they have only a few points in common, but many deflationists would probably agree on these two points:

-

(D1)

Truth is not a substantial property.

-

(D2)

Truth owes its raison d’etre to its logico-linguistic function.

The thesis (D1) is the core doctrine of deflationism about truth. What exactly it means is not clear and may vary among deflationists, but only one implication that (D1) is alleged to have will be important in this article, namely, that we should not be able to obtain any new substantial knowledge of non-semantic facts by invoking the notion of truth. The thesis (D2) will be closely examined in Sect. 3.

Here I follow Horsten (2011) and call the function of truth logico-linguistic. Some deflationists like Field (1994, 1999) simply call it logical, but I agree with Horsten that truth is also a linguistic notion, since truth operates on linguistic entities (broadly interpreted)—the bearers of truth. Furthermore, as Halbach (2001) points out, truth can’t be purely logical in the sense that it is ontologically neutral, since quite modest truth axioms imply the existence of at least two distinct objects. In this article, I assume, to avoid unnecessary complications, that the bearers of truth are sentence types; but my arguments can be applied to theories of truth with other truth bearers mutatis mutandis.

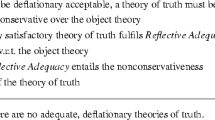

Horsten (1995), Shapiro (1998) and Ketland (1999) independently presented the so-called conservativeness argument against deflationism about truth. Their arguments are actually based upon a specific formal conception of ‘theory of truth’, in which theories of truth are given as a result of adding a truth predicate and its axioms on top of some axiomatic formal theory. That is to say, we first fix some recursively axiomatised theory \(\mathsf {B}\), such as Peano Arithmetic (\(\mathsf {PA}\)) and Zermelo–Fraenkel Set Theory (\(\mathsf {ZF}\)), of the subject matter in question, which is called a base theory. Then we add a truth predicate \( T \) to the language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\) of \(\mathsf {B}\) and a recursive set \(\mathcal {T}\) of axioms for \( T \) to \(\mathsf {B}\); we call the resulting theory an axiomatic theory of truth over\(\mathsf {B}\) (or, over the subject matter in question, such as arithmetic and set theory, when we need not specify the base theory). Now, with this formal conception of ‘theory of truth’, the conservativeness argument aims to pose the following dilemma:

-

(C1)

A deflationary theory \(\mathsf {S}\) of truth must be conservative over its base theory \(\mathsf {B}\): that is, an \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\)-sentence \(\sigma \) must be provable in \(\mathsf {B}\) whenever it is provable in \(\mathsf {S}\).

-

(C2)

However, no adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\) can be conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\).Footnote 1

Throughout this article I take the standpoint that Azzouni (1999) calls first-order deflationist: namely, I commit myself to the ordinary effective notion of first-order logical consequence, and the word ‘provable’ always means the provability in the sense of the ordinary first-order logic unless otherwise specified.Footnote 2

The presupposition of the clear distinction between the base part \(\mathsf {B}\) and the truth part \(\mathcal {T}\) of a theory \(\mathsf {S}\) of truth is necessary for the conservativeness argument; otherwise, the conservativeness requirement (C1) would make no sense. Furthermore, the distinction of the truth and base parts must be given in the way that the truth predicate \( T \) is fresh to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\) and \(\mathsf {B}\) tells us nothing about \( T \). In order for (C1) to be a reasonable requirement, the base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) must formally theorise about its subject matter (to the extent that it serves one’s purpose) without any help from \( T \); otherwise, truth would play a substantial (‘inflationary’) role in theorising about the subject matter, and new axioms \(\mathcal {T}\) for such a substantial factor in the theorisation of the subject matter might well yield new theorems about the subject matter.Footnote 3 Accordingly, we may also assume that \(\mathsf {B}\) is a theory of non-semantic subject matter, unless we are interested in formalising the Tarskian hierarchy of truths in which truths of higher levels are applied to truths of lower levels. The most common form of axiomatic theories of truth, such as the ones found in (Halbach 2010), is consonant with the so far described formal conception of ‘theory of truth’.Footnote 4

The conservativeness argument has been criticised by Azzouni (1999), Field (1999), Tennant (2002) and others; then Horsten (2011), Shapiro (2004) and Ketland (2005, 2010) gave counterarguments to these criticisms. A plethora of arguments have been exchanged back and forth between those and many others, and the conservativeness argument forms a central topic of the debate on deflationism about truth nowadays. My view is, however, that many of these debates are placed in an inappropriate setting.

The study of axiomatic theories of truth has so far centred around those over arithmetic, and philosophical debates concerning axiomatic theories of truth have been based on formal results about those theories of truth over arithmetic. The debate on the conservativeness argument so far is no exception to this trend. This is presumably not because philosophers are only interested in arithmetical truth. Rather, it is probably because they believe that theories of truth over arithmetic provide a ‘generic’ case and most of the relevant results concerning them and philosophical arguments based on those results can be generalised to other cases. However, I doubt the validity of this extrapolation and suspect that theories of truth over arithmetic do not constitute such a generic case. Recent research in formal logic, such as (Fujimoto 2012, 2017), reveals certain significant dissimilarities between axiomatic theories of truth over arithmetic and those over set theory, and we will see a further example of such dissimilarity in this article. These formal results indicate that theories of truth over arithmetic do not constitute such a generic case.

My proposal in this article is that the appropriate formal setting for evaluating the adequacy or inadequacy of the conservativeness argument is provided not by theories of truth over arithmetic but by those over much ‘richer’ subject matters such as set theory. The move to this new formal setting provides deflationists with better defence against the conservativeness argument, but the goal of this article is not to refute the conservativeness argument. My primary goal in this article is to give a closer examination of the formal assumptions upon which the conservativeness argument relies, and thereby to uncover a new area of debate on deflationism and the conservativeness argument, to which the previous debates in the literature on theories of truth over arithmetic cannot be straightfowardly generalised.

2 The conservativeness requirement

One peculiar but important feature of the notion of truth is its ‘universality’: truth is topic-neutral and can be applied to any (declarative) sentence about any subject matter. Many philosophers would probably agree on this, but we have to be careful when formally spelling it out. We have supposed that truth is a linguistic device operating on sentences. Hence, any theory of truth must be accompanied by some theory of syntax as the theory of its bearers. There are, however, different methods of incorporating a theory of syntax into a theory of truth.Footnote 5 In this article, I focus on the most customary method in which the following condition (Syn) on base theories is assumed:

-

(Syn)

A base theory contains a theory of syntax (either intrinsically or via coding), which plays the role of the theory of truth bearers, and on which the truth predicate operates.

There are two different cases to be separately considered concerning how a theory of syntax is ‘contained’ in a base theory. Theories of some subject matters intrinsically contain a theory of syntax per se, but others do not; for instance, a reasonably strong theory of sets intrinsically contains a theory of syntax (such as a theory of finite strings of symbols of some alphabet, where those symbols may be treated as urelements), while the intended domain of arithmetic contains nothing syntactic and a theory of natural numbers is not intrinsically concerned with syntax per se; in the latter case, a theory of syntax must be embedded in a base theory via a certain coding schema such as Gödel numbering. Note that (Syn) is a quite exclusive condition; theories of many subject matters, such as biology and medicine, do not necessarily contain any theory of syntax either intrinsically or via coding, and cannot be bases of theories of truth under the assumption of (Syn). As I will illustrate in Sect. 5, the conservativeness argument crucially relies upon the assumption of (Syn).

The universality of truth suggests that in the debate on truth we should take into account theories of truth over subject matters other than arithmetic, at least on equal terms with those over arithmetic. Even under the assumption of (Syn), we have many different theories of different subject matters available as bases of theories of truth. Hence, we have a variety of base theories that we can take in place of \(\mathsf {B}\) in the components (C1) and (C2) of the conservativeness argument. However, the veracity of the claim (C2), that no adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\) is conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\), depends not only on what theory of truth is taken to be adequate but also on what base theory is taken in place of \(\mathsf {B}\); if \(\mathsf {B}\) is inconsistent, then (C2) is trivially false, no matter what theory of truth is taken to be adequate; even if \(\mathsf {B}\) is consistent, we can still construct an artificial counterexample to (C2) in many cases.Footnote 6 Hence, a natural question to ask is: What base theories are to be taken into account in (C1) and (C2)?

Since deflationists hold that truth is a logical device, they may well contend that it should be applicable not only to arbitrary subject matters but also to arbitrary base theories of the subject matters, as other logical devices are. Hence, a naïve answer to the aforementioned question is perhaps the following:

-

(C3)

The requirement (C1) should be applied to any base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) of any subject matter, as long as \(\mathsf {B}\) meets the condition (Syn).

(C3) makes the task of the proponents of the conservativeness argument easier, since then they have only to find at least one base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) of one subject matter, from a large variety of options, such that no adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\) is conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\). I suspect that this (C3) is implicitly assumed by many proponents of the conservativeness argument and that this is why they are content to only consider a single base theory \(\mathsf {PA}\) and take the non-conservativeness of some theories of truth over \(\mathsf {PA}\) as a ‘witness’ of the substantiality of truth. One of my goals in this article is to argue that we should reject (C3) and exclude some subject matters and base theories, arithmetic in particular, from the scope of (C1).

3 Logico-linguistic functions of truth

In this section, I will specify one minimal requirement for adequate theories of truth through consideration of the logico-linguistic function of truth.

Deflationism about truth claims that truth is a mere logico-linguistic device. The first question to ask is: what is the logico-linguistic function of truth? It is often claimed by deflationists that truth is a device of ‘indirect endorsement’ and ‘infinite conjunction’. The use of truth as a device of indirect endorsement is exemplified in statements like ‘what Karl said at the trial is true’, in which one endorses what Karl said at the trial without bothering to write down it or even without knowing exactly what he said. This function of truth is normally achieved by means of the truth predicate \( T \) and definite descriptions of the sentences one wants to endorse; for instance, given a definite description Kx of the sentence that Karl asserted at the trial, we can formally express ‘what Karl said at the trial is true’ by \(\forall x ( K x \rightarrow T x )\). The use of truth as a device of infinite conjunction is exemplified in sentences like ‘all axioms of \(\mathsf {ZF}\) are true’, in which the truth of infinitely many sentences are asserted; we first pick a predicate \(\mathcal {A} x\) characterising the set of the axioms of \(\mathsf {ZF}\), such that \(\mathcal {A} x\) holds if and only if x is (a code of) an axiom of \(\mathsf {ZF}\), and thereby formally express the sentence by \(\forall x ( \mathcal {A} x \rightarrow T x )\).

The second question to ask is: what truth axioms are needed to properly implement the logico-linguistic function of truth? In this article, I will focus on two kinds of theories of truth, which are particularly at issue in the debate on the conservativeness argument. Given a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) and its language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\), let \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\) be the language of theories of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\), which is obtained by adding a truth predicate \( T \) or a satisfaction predicate \( Sat \) to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\); the choice between \( T \) and \( Sat \) depends on the theory of truth at stake and its specific formulation, but I will be deliberately sloppy about the distinction between them to avoid unnecessary technical complications and always assume that the truth predicate \( T \) is explicitly defined in terms of \( Sat \) when \( Sat \) is taken as a primitive predicate symbol of \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\).Footnote 7 We first consider purely disquotational theories  and \(\mathsf {TB}\) of truth. The theory

and \(\mathsf {TB}\) of truth. The theory  of truth over a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is obtained by extending \(\mathsf {B}\) with the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) of \( T \)-biconditionals for \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\):

of truth over a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is obtained by extending \(\mathsf {B}\) with the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) of \( T \)-biconditionals for \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\):

where \(\ulcorner \sigma \urcorner \) denotes a code (or a name) of an \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\)-sentence \(\sigma \). Now, some base theories, such as \(\mathsf {PA}\), contain axiom schemata, such as the schema of arithmetical induction, but no instance of the axiom schemata containing \( T \) is added to  as an axiom. So, let \(\mathsf {TB}\) denote the extension of

as an axiom. So, let \(\mathsf {TB}\) denote the extension of  obtained by extending all the axiom schemata of \(\mathsf {B}\), if any, to the entire language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\). For an important example, let us write \(\mathcal {L}\text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) for the schema of arithmetical induction for a language \(\mathcal {L}\) extending the language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}\) (\({=} \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {PA}} = \{ 0, S , +, \times , < \}\)) of first-order arithmetic, i.e.,

obtained by extending all the axiom schemata of \(\mathsf {B}\), if any, to the entire language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\). For an important example, let us write \(\mathcal {L}\text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) for the schema of arithmetical induction for a language \(\mathcal {L}\) extending the language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}\) (\({=} \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {PA}} = \{ 0, S , +, \times , < \}\)) of first-order arithmetic, i.e.,

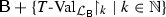

then the theory \(\mathsf {TB}\) over \(\mathsf {PA}\) is obtained from  over \(\mathsf {PA}\) by adding \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\). We secondly consider compositional theories

over \(\mathsf {PA}\) by adding \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\). We secondly consider compositional theories  and \(\mathsf {CT}\) of typed truth. The theory

and \(\mathsf {CT}\) of typed truth. The theory  over a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is obtained by augmenting \(\mathsf {B}\) with the axioms expressing the inductive clauses of the Tarskian definition of truth, such as ‘for all \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\)-sentences \(\sigma \), \(\lnot \sigma \) is true iff \(\sigma \) is not true’; see (Ketland 1999, pp. 79–80) or (Halbach 2010, p. 65) for more formal details. The crucial difference between

over a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is obtained by augmenting \(\mathsf {B}\) with the axioms expressing the inductive clauses of the Tarskian definition of truth, such as ‘for all \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\)-sentences \(\sigma \), \(\lnot \sigma \) is true iff \(\sigma \) is not true’; see (Ketland 1999, pp. 79–80) or (Halbach 2010, p. 65) for more formal details. The crucial difference between  and

and  is that each truth axiom of

is that each truth axiom of  involves quantification over all sentences and states some property of truth about all sentences at once, whereas each truth axiom of

involves quantification over all sentences and states some property of truth about all sentences at once, whereas each truth axiom of  is an instance of the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) and only refers to a single sentence. It is known that

is an instance of the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) and only refers to a single sentence. It is known that  is a sub-theory of

is a sub-theory of  over any base theory, but the converse does not hold.Footnote 8 The theory \(\mathsf {CT}\) is obtained from

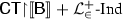

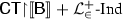

over any base theory, but the converse does not hold.Footnote 8 The theory \(\mathsf {CT}\) is obtained from  by extending all the axiom schemata of \(\mathsf {B}\), if any, to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\); e.g., \(\mathsf {CT}\) over \(\mathsf {PA}\) is defined as

by extending all the axiom schemata of \(\mathsf {B}\), if any, to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\); e.g., \(\mathsf {CT}\) over \(\mathsf {PA}\) is defined as  over \(\mathsf {PA}\) plus \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\). In what follows, when we consider a theory of truth over a particular base theory, we indicate it by putting it in double square brackets

over \(\mathsf {PA}\) plus \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\). In what follows, when we consider a theory of truth over a particular base theory, we indicate it by putting it in double square brackets  ; e.g.,

; e.g.,  means the theory \(\mathsf {CT}\) over \(\mathsf {PA}\).

means the theory \(\mathsf {CT}\) over \(\mathsf {PA}\).

The theory  is often seen as sufficient for capturing the aforementioned two functions of truth (e.g., Halbach 1999). However, some deflationists think that

is often seen as sufficient for capturing the aforementioned two functions of truth (e.g., Halbach 1999). However, some deflationists think that  is insufficient and

is insufficient and  needs to be part of any adequate deflationary theory of truth.Footnote 9 In fact, the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) alone does not license us to make deductions of a certain type that we expect to be able to make by means of truth. Consider the following deductive inference.Footnote 10

needs to be part of any adequate deflationary theory of truth.Footnote 9 In fact, the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) alone does not license us to make deductions of a certain type that we expect to be able to make by means of truth. Consider the following deductive inference.Footnote 10

-

(a)

What Karl said at the trial is true.

-

(b)

Judy said that what Ikoma said contradicts what Karl said.

-

(c)

Therefore, if what Judy said is true, then what Ikoma said is false.

Let \( K x\), \( J x\), and \( I x\) be predicates that give definite descriptions of what Karl, Judy, and Ikoma said respectively, and let x, y, and z be the unique sentences such that \( K x\), \( J y\), and \( I z\). Here, we need not explicitly specify what sentences Karl and Ikoma said. Now, suppose (a) and (b). Then, what Judy said (\({=} y\)) is that what Ikoma said (\({=} z\)) implies the negation of what Karl said (\({=} x\)); namely, we have  , where we write

, where we write  for a representation (or a code) of a syntactic operation h (see Halbach 2010, p. 32). Further suppose what Judy said is true, that is, \( T y\). By the above equation, we have

for a representation (or a code) of a syntactic operation h (see Halbach 2010, p. 32). Further suppose what Judy said is true, that is, \( T y\). By the above equation, we have  . From this, we want to deduce \(T z \rightarrow \lnot T x\), by which we immediately obtain \(\lnot T z\) because we have supposed (a), i.e., \( T x\). However, we do not know exactly what Karl and Ikoma said; we are only given their definite descriptions and certain objects that satisfy the descriptions. In order to use \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) in a deduction, we need to explicitly specify a sentence \(\sigma \) to which we apply the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\). Hence, without knowing exactly what Karl and Ikoma said, the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) cannot be used for deducing \(T z \rightarrow \lnot T x\) from

. From this, we want to deduce \(T z \rightarrow \lnot T x\), by which we immediately obtain \(\lnot T z\) because we have supposed (a), i.e., \( T x\). However, we do not know exactly what Karl and Ikoma said; we are only given their definite descriptions and certain objects that satisfy the descriptions. In order to use \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) in a deduction, we need to explicitly specify a sentence \(\sigma \) to which we apply the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\). Hence, without knowing exactly what Karl and Ikoma said, the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\) cannot be used for deducing \(T z \rightarrow \lnot T x\) from  .Footnote 11 Therefore, we cannot implement the desired deduction in

.Footnote 11 Therefore, we cannot implement the desired deduction in  nor \(\mathsf {TB}\), and we would need some general principles such as ‘for all \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\)-sentences v and w,

nor \(\mathsf {TB}\), and we would need some general principles such as ‘for all \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\)-sentences v and w,  is true if and only if the truth of v implies the truth of w’. In this example, we give a deductive argument about the truth of some sentences by analysing and manipulating their logico-syntactic structures without explicitly specifying exactly what these sentences are. Let us call this type of deductive reasoning blind deduction.Footnote 12 Neither

is true if and only if the truth of v implies the truth of w’. In this example, we give a deductive argument about the truth of some sentences by analysing and manipulating their logico-syntactic structures without explicitly specifying exactly what these sentences are. Let us call this type of deductive reasoning blind deduction.Footnote 12 Neither  nor \(\mathsf {TB}\) enables us to carry out blind deduction in general, and the axioms of

nor \(\mathsf {TB}\) enables us to carry out blind deduction in general, and the axioms of  or something equivalent are necessary. Hence, in what follows, I assume that the axioms of

or something equivalent are necessary. Hence, in what follows, I assume that the axioms of  are a minimal requirement for adequate theories of truth, and thus any adequate deflationary theory of truth must prove the axioms of

are a minimal requirement for adequate theories of truth, and thus any adequate deflationary theory of truth must prove the axioms of  .

.

Another function or feature that may well be required of truth is self-applicability. Suppose Karl said ‘Everything the Pope says is true’ and the Pope said ‘Everything Judy says is true’. Then what Karl said should entail whatever Judy says. To formally implement this reasoning in a theory of truth, the theory should contain some axioms that enable iterative application of the truth predicate, since what Karl said entails what Judy says by way of what the Pope said, which involves the truth predicate. Truth-theorists ultimately have to settle the problem of what axioms are adequate for self-applicable truth, but this problem is far from settled and beyond the scope of this article, and so let us restrict our discussion to non self-applicable (‘typed’) truth; it is to be noted that the above example of blind deduction does not require any self-application of truth for the argument to go through, and we can simply assume that what Karl, Judy, and Ikoma said do not contain the truth predicate; hence, even with this restriction, we still need the axioms of  as a minimal requirement for adequate theories of truth.

as a minimal requirement for adequate theories of truth.

4 Two conservativeness arguments

I will introduce two variants of the conservativeness argument that are not vulnerable to the existing objections in the literature. The conclusion I will draw in the subsequent sections is that both arguments are hard to counter if one confines one’s attention to theories of truth over arithmetic, but the difficulty they pose to deflationism can be overcome by turning to other kinds of bases, which gives a support and motivation to my proposal.

4.1 Induction as a syntactic principle

The theory  is known to be non-conservative over \(\mathsf {PA}\), and its non-conservativeness is often considered by proponents of the conservativeness argument as evidence of the substantiality of truth, whereas

is known to be non-conservative over \(\mathsf {PA}\), and its non-conservativeness is often considered by proponents of the conservativeness argument as evidence of the substantiality of truth, whereas  is conservative over \(\mathsf {PA}\). The difference between

is conservative over \(\mathsf {PA}\). The difference between  and

and  lies in whether the schema of arithmetical induction is restricted to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}\) or extended to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+}\). Hence, those proponents need to establish that an adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {PA}\) must prove the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) of arithmetical induction for the extended language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+}\).

lies in whether the schema of arithmetical induction is restricted to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}\) or extended to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+}\). Hence, those proponents need to establish that an adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {PA}\) must prove the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) of arithmetical induction for the extended language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+}\).

A paradigmatic example of such an argument to this end is proposed by Shapiro and it appeals to the indefinite extensibility of arithmetical induction. Shapiro (1998) advocates the following view:

-

(S1)

Commitment to all instances of arithmetical induction with any predicate of natural numbers constitutes our understanding of the concept of natural number, and thus the schema of arithmetical induction should be conceived as indefinitely extensible to any newly introduced predicate of natural numbers.Footnote 13

This leads him to make the next general claim:

-

(S2)

Any adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\) must prove \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\), whenever the subject matter of \(\mathsf {B}\) includes arithmetic.

In his rejoinder to Shapiro, Field (1999) points out that (S1) does not imply (S2). His argument relies on the next two theses:

-

(F1)

One should not conclude from the non-conservativeness of a theory of truth \(\mathsf {S} = \mathsf {B} + \mathcal {T}\) over \(\mathsf {B}\) that truth is substantial without first showing that each truth axiom of \(\mathcal {T}\) is ‘essential to truth’ and postulated solely by virtue of the nature of truth.

-

(F2)

The indefinite extensibility of the axiom schemata of the base theory \(\mathsf {B}\), if it is required by anything about the non-semantic subject matter of \(\mathsf {B}\), is not part of the deflationary concept of truth, and the extension of any of them is not an axiom ‘essential to truth’.

Thereby he concludes that the non-conservativeness of  is not a problem for deflationists, since the indefinite extensibility at issue is derived from ‘something about our idea of natural numbers’ and ‘nothing about truth’ (p. 539).Footnote 14

is not a problem for deflationists, since the indefinite extensibility at issue is derived from ‘something about our idea of natural numbers’ and ‘nothing about truth’ (p. 539).Footnote 14

There is, however, another route to (S2), not by way of (S1), which evades Field’s argument. Sentences and formulae of a formal language are recursively defined, and induction on the construction (or complexity) of them is an indispensable theorem-proving tool in meta-mathematics. Let us call inductive inference along the recursive construction of the syntactic structure of a formal language syntactic induction. Syntactic induction may be formulated in different ways, but a typical example of its formulation is:

-

(SI)

Let \(\Phi \) be any predicate of formulae. Suppose that \(\Phi \) holds for all atomic formulae, and that if \(\Phi \) holds for all sub-formulae of A, then \(\Phi \) holds for A. Then \(\Phi \) holds for all formulae.

In general, the way we understand how the sentences of a language are constructed is essentially of this inductive nature, and it naturally commits us to syntactic induction like (SI).Footnote 15 One can thereby argue that the indefinite extensibility of syntactic induction to any newly introduced predicate of syntactic objects constitutes our understanding of the syntactic structure of any formal language no less than the indefinite extensibility of arithmetical induction constitutes our understanding of natural numbers. Therefore, whenever we use a theory of syntax for any purpose, we are committed to the indefinite extensibility of syntactic induction.

Now, recall that truth is a logico-linguistic predicate operating on syntactic objects and every theory of truth must accompany an appropriate theory of syntax. Hence, our commitment to the indefinite extensibility of syntactic induction is made prior to having any particular theory of truth and independently of any epistemic and/or mathematical commitment that we might make as to its base theory and subject matter. This suggests that the schema of syntactic induction, such as (SI), for the entire language of theories of truth is a necessary part of any adequate theory of truth; it is not essential only to truth but essential to truth and its necessary companion. Further recall that we have assumed (Syn), which says that every base theory must contain an appropriate theory of syntax on which truth operates. In particular, when a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is arithmetical, a theory of syntax needs to be embedded in \(\mathsf {B}\) via Gödel numbering, and thus induction on natural numbers and induction on syntactic objects are inevitably ‘entangled’ within \(\mathsf {B}\). If we simply identify these two induction principles, an adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {PA}\) should include  and non-conservativeness thus results.

and non-conservativeness thus results.

Our deflationist might try to avoid this non-conservativeness consequence by only postulating the schema of syntactic induction for \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+}\), in the form of (SI) or similar, as a distinct and separate principle from \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\), without identifying them. However, natural numbers and syntactic objects are so intimately and deeply entangled in arithmetical base theories that the schema of syntactic induction actually implies the schema of arithmetical induction; for instance, the schema (SI) for \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+}\) implies \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\).Footnote 16 Even if we postulate the schema of syntactic induction in a form other than (SI), the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) is still implied thereby in most cases.Footnote 17 This is a quite general phenomenon, as is expected from the folklore view that the theory of syntax is essentially the same thing as arithmetic.Footnote 18 Hence, in particular,  plus the schema of syntactic induction for \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+}\) is just equal to

plus the schema of syntactic induction for \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{+}\) is just equal to  anyway and thus not conservative over \(\mathsf {PA}\).

anyway and thus not conservative over \(\mathsf {PA}\).

This is what I call the syntactic conservativeness argument: it aims at establishing (S2), not on the basis of the indefinite extensibility of arithmetical induction, but on the basis of that of syntactic induction. Field’s theses (F1) and (F2) do not seem to help us evade this variation of the conservativeness argument, since the extension of syntactic induction to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\) is not required by something about the non-semantic subject matter of the theory of truth in question but rather required by the constitutive element of our understanding of the syntactic structure of formal languages.

4.2 Commitment to logic

One major issue concerning the logico-linguistic function of truth, in the context of the conservativeness argument, is whether truth should not only express infinite conjunctions but also establish some of them. Let \( Bew _{\mathsf {B}} ( x )\) be a canonical provability predicate for \(\mathsf {B}\) expressing ‘x is an \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\)-sentence provable from \(\mathsf {B}\)’. The so-called global reflection principle \( GRef _{\mathsf {B}}\) for a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) denotes an \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\)-sentence \(\forall x \bigl ( Bew _{\mathsf {B}} ( x ) \rightarrow T x \bigr )\), which expresses that all theorems of \(\mathsf {B}\) are true. This \( GRef _{\mathsf {B}}\) is a principal example of an infinite conjunction that is claimed by proponents of the conservativeness argument to be a necessary consequence of any adequate theory of truth. They then conclude that truth is substantial, since \( GRef _{\mathsf {PA}}\) implies the consistency statement \( Con ( \mathsf {PA} )\) for \(\mathsf {PA}\) in the presence of \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {TB}\).

According to deflationism, the main point of having a truth predicate is that it increases one’s expressive power via its logico-linguistic function. When we introduce a new expression into our vocabulary, we usually do not expect that its introduction by itself brings about any new substantive knowledge. From the deflationist point of view, therefore, truth enables us to express infinite conjunctions, but it is not part of a deflationary theory of truth to verify or refute each given infinite conjunction, no matter how obvious its truth or falsity is. Hence, our proponent of the conservativeness argument has to provide a special reason why that particular infinite conjunction \( GRef _{\mathsf {B}}\) should be established by every adequate (deflationary) theory of truth.

I will first consider one key example of an argument for this claim and refute it, by which I intend to give a preliminary picture of what kind of infinite conjunction need not be a consequence of an adequate deflationary theory of truth. The argument I will consider is a variation of Ketland’s ‘reflective argument’ (2005). The key thesis behind it is Feferman’s influential view on ‘implicit commitment’: if one accepts a mathematical theory \(\mathsf {S}\), then one is implicitly committed to accepting a number of further statements, such as \( Con ( \mathsf {S} )\) and proof-theoretic reflection principles for \(\mathsf {S}\), that are not provable in \(\mathsf {S}\) (e.g., see Feferman 1991). Following Ketland, let us call the ‘further statements’ to which one is implicitly committed in accepting \(\mathsf {S}\) the reflective consequences of \(\mathsf {S}\). Then, the argument goes that any adequate theory of truth must derive the reflective consequences of its base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) that are expressible in the language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\) and that \( GRef _{\mathsf {B}}\) is indeed among those reflective consequences. However, Field’s thesis (F1) provides an immediate deflationist rebuttal to this type of argument. Any implicit commitment to a reflective consequence of an initially accepted theory is not something required by virtue of truth but rather required by one’s very acceptance of the theory and one’s specific epistemic and/or mathematical attitude toward the theory and/or its subject matter. Hence, the reflective consequences of any given base theory and/or its subject matter is not ‘essential to truth’, and thus it follows from (F1) that any non-conservativeness they cause does not undermine deflationism. In conclusion, the ‘reflective argument’ fails to establish that \( GRef _{\mathsf {B}}\), or any other reflective consequence such as ‘all axioms of \(\mathsf {B}\) are true’, ought to be a consequence of an adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\).

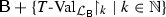

I have so far argued that it is not required of a deflationary theory of truth, say \(\mathsf {S}\), to prove some statement \( P \) solely on the ground that \( P \) is a reflective consequence of the base theory\(\mathsf {B}\) of \(\mathsf {S}\). However, this does not exclude the possibility that the provability of some reflective consequences turns out to be necessary part of \(\mathsf {S}\) for some reason other than their being reflective consequences of \(\mathsf {B}\). Now, it seems still possible and reasonable to argue that a certain positive commitment to the logic one employs is a precondition for formulating any theory \(\mathsf {B}\) of one’s subject matter and any theory of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\), regardless of one’s mathematical and/or epistemic attitude to \(\mathsf {B}\) and its subject matter, and there may be a non-conservative truth-theoretic principle that is required, by this commitment to logic, to be a consequence of every adequate theory of truth.Footnote 19 There is one strong argument that expands on this point. First note that we can formally express the following statement in \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\):

Then, Cieśliński (2010) made a significant observation that \( GRef _{\mathsf {PA}}\) is equivalent over  to \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}} }\).Footnote 20 He thereby suggests that ‘it is perhaps not so much the relation between truth and \(\mathsf {PA}\), but between truth and logic ...which matters’ (p. 415). In other words, \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}} }\) is a ‘reflective consequence’ not of the base theory \(\mathsf {PA}\) and/or its mathematical subject matter but rather a ‘reflective consequence’ of logic, to which one is committed prior to having any theory of truth or anything else.

to \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}} }\).Footnote 20 He thereby suggests that ‘it is perhaps not so much the relation between truth and \(\mathsf {PA}\), but between truth and logic ...which matters’ (p. 415). In other words, \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}} }\) is a ‘reflective consequence’ not of the base theory \(\mathsf {PA}\) and/or its mathematical subject matter but rather a ‘reflective consequence’ of logic, to which one is committed prior to having any theory of truth or anything else.

Cieśliński’s result may well give our deflationist a compelling reason to take the provability of \( GRef _{\mathsf {PA}}\) as among the essential requirements for her theory of truth over \(\mathsf {PA}\). Field’s and other existing deflationist counterarguments seem unable to cope with this variation of the conservativeness argument, which supports (C2) by appealing to the non-conservativeness of some principle concerning logic. However, the proof of Cieśliński’s theorem is very peculiar to arithmetic and does not apply to theories of truth over other subject matters, since it crucially depends on the fact that each instance \(\varphi ( \overline{0} ) \wedge \forall x ( \varphi ( x ) \rightarrow \varphi ( x + 1 ) ) \rightarrow \varphi ( \overline{n} )\) on the numerals \(\overline{n}\) of \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) is logically valid, but we do not expect the same for other mathematical axiom schemata such as the collection schema of set theory. In fact, as we will see in Sect. 6, the principle \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} }\) adds no substance to reasonably rich set-theoretic base theories \(\mathsf {B}\), and thus \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} }\) is not equivalent to \( GRef _{\mathsf {B}}\) in general; furthermore, \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} }\) does not even imply the statement ‘all axioms of \(\mathsf {B}\) are true’ in general.

Let me summarise the argument in this section. Both the syntactic conservativeness argument and Cieśliński’s argument point to certain general conditions for adequate theories of truth derived from consideration of our ex-ante commitment in having any theory of truth regardless of our choice of subject matter and base theory. This is why Field’s and other existing defences of deflationism are unable to cope well with the two arguments, since these are designed only to avoid the requirements for non-conservative truth-theoretic principles that flow from our ex-post commitment concerning an already chosen particular subject matter and/or base theory.

5 Theory of syntax and arithmetic

In this section, I will discuss the legitimacy and significance of the assumption of (Syn) through examination of a recently proposed new type of theory of truth.

When a theory of truth is formulated over an arithmetical base theory, the base theory has to play two different roles at the same time, i.e., the roles of a theory of arithmetic and a theory of syntax. The equivalence of syntactic and arithmetical inductions in theories of truth over arithmetic, discussed in Sect. 4.1, comes from this very entanglement of the two roles within a single theory. This is an inevitable consequence under the assumption of (Syn). By contrast, in our ordinary informal meta-mathematical discourse, the theory of syntax and that of natural numbers are kept separate, and syntactic objects and natural numbers are treated as distinct objects.

Having reflected upon this dissonance between the customary methodology in axiomatic theories of truth and our informal meta-mathematics, Heck (2009), Halbach (2010, Ch. 21) and Leigh and Nicolai (2013) proposed a new type of theory of truth in which a theory of syntax is given as a completely separate theory from the base theory \(\mathsf {B}\), with a new domain of its own objects separate from the domain of the non-semantic objects of \(\mathsf {B}\). This new type of theory of truth is quite versatile and can be applied to literally any formal theory of any subject matter, whether or not it is rich enough to develop a theory of syntax within it. Hence, the universality of truth, discussed in Sect. 2, is better captured by this formal setting than our current one with the exclusive condition (Syn). More importantly, theories of truth of this type are always conservative over their base theories even in the presence of the extended syntactic induction as well as Cieśliński’s principle in terms of the separate ‘disentangled’ theory of syntax.Footnote 21 This general conservation result indicates that (Syn) is a crucial and indispensable assumption implicit in the conservativeness argument: indeed, all the arguments for the claim (C2) presented so far in the literature are only valid under the assumption of (Syn) and, if we adopt theories of truth with a disentangled theory of syntax, conservativeness results in all the known relevant cases. So, one easy way out for deflationists from the predicament at issue, posed by the syntactic conservativeness argument and Cieśliński’s argument, is to abandon the assumption of (Syn) by taking up this new formal conception of ‘theory of truth’. However, this is not a genuine solution to the problem. Theories of truth of this type with a disentangled theory of syntax turn out to be unnatural and inappropriate when we think of the ultimate goal of theories of truth.Footnote 22

A primary purpose of the axiomatic approach to truth is to provide a minimal framework for implementing the notion of truth onto a maximally rich theory in the sense that we do not want to ascend beyond it to a meta-language and a meta-theory even richer than it in non-semantic content. A typical example of a maximally rich theory is the theory within which one carries out all her mathematical investigation. For instance, suppose one wants to give a theory of truth over the theory \(\mathsf {M}\) of one’s entire mathematics. If she wants to define a truth predicate over \(\mathsf {M}\) by mathematical means, she has to ascend to some meta-theory richer in mathematical content than \(\mathsf {M}\) due to Tarski’s theorem; for example, if \(\mathsf {M}\) is \(\mathsf {ZF}\), then she has to ascend to some richer theory, such as the Morse-Kelly theory \(\mathsf {MK}\) of classes, to define the truth over \(\mathsf {ZF}\). In this situation, one would prefer to dispense with ascent to any such meta-theory, as otherwise her mathematics would be enlarged by the new mathematical content of such a meta-theory and thus \(\mathsf {M}\) would no longer be the theory of her entire mathematics. Here is the point where the axiomatic approach to truth comes into play: we introduce truth as an undefined primitive predicate and also as a non-mathematical logico-linguistic notion, and then directly characterise it by listing its axioms, which requires no addition of mathematical substance.Footnote 23 Another example of a maximally rich theory is the theory \(\mathsf {W}\) of one’s entire (non-semantic) science, say, the conglomerate of one’s current best theories of mathematics, physics, chemistry, and so forth; then, the subject matter of this theory is everything she investigates in science and its language is the (non-semantic) part of her natural language used in her scientific discourse. Surely, she would not like to change her theory of physics or any other scientific discipline only for the sake of having a truth predicate for her natural language. Most philosophers, I think, are ultimately interested in the theory of truth for such maximally rich theories and subject matters and, as the above examples indicate, some of them, such as \(\mathsf {M}\) and \(\mathsf {W}\), are naturally presumed to be indeed quite ‘rich’ so that they intrinsically contain a theory of syntax per se and even develop substantial meta-mathematics on the basis of the theory of syntax therein.Footnote 24

Now, for such ‘rich’ theories, adding another theory of syntax separately from the existing theory of syntax intrinsically contained in them is quite unnatural and even unsound. In the case of theories of truth with a disentangled theory of syntax, many syntactic statements, such as the consistency statement for the base theory \(\mathsf {B}\), are provable in terms of the newly added theory of syntax, but those statements are not provable in terms of the intrinsic theory of syntax of \(\mathsf {B}\); namely, the two theories of syntax behave differently and have incompatible consequences. Hence, while the assumption of (Syn) is not necessary and theories of truth with a disentangled theory of syntax behave ideally for deflationists in many cases, where base theories are relatively weak (‘poor’), the assumption of (Syn) is still indispensable and those theories with a disentangled theory of syntax are unnatural and inappropriate in other cases, where base theories are ‘rich’.Footnote 25 The consideration of maximally rich theories indicates that there is indeed a case where theories of truth with a disentangled theory of syntax are not appropriate and we really need to pursue axiomatic theories of truth over a ‘rich’ base theory with the assumption of (Syn). Hence, theories of truth with a disentangled theory of syntax do not provide a general solution to the dilemma posed by the conservativeness argument, when we take a broader range of subject matters and theories into account as the bases of theories of truth.

6 Beyond arithmetic

Now we have arrived at the main section of this paper, and I will elaborate on my proposal.

The preceding discussion of the assumption of (Syn) gives a new perspective to the debate on the conservativeness argument. It is theories of truth over ‘rich’ subject matters and base theories that essentially need the assumption of (Syn). A typical example of such a ‘rich’ subject matter (in mathematics) is set theory, but arithmetic is deemed to be not ‘rich’ enough in the sense at issue. Arithmetic does not treat syntactic objects as its intended subject matter, and any mathematical theory about or built up on the basis of those syntactic objects is not part of arithmetic per se. So, the debate on the conservativeness argument so far has been misplaced in an atypical formal setting for the assumption of (Syn).

Does the non-conservativeness of some theories of truth obtained in the ‘atypical’ setting, where these theories of truth are formulated over arithmetic with the assumption of (Syn), still imply the substantiality of truth? My answer is no. According to the aforementioned folklore view, the mathematical structure that the theory of syntax describes is essentially the same as the mathematical structure of natural numbers, and thus arithmetic is indeed a minimal basis for theories of truth under the assumption of (Syn). An arithmetical base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is at the same time a theory of syntax, and the non-semantic base content and the syntactic content of a theory of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\) become almost identical. With this ‘entanglement’, a theory of truth over arithmetic can then be seen as having little or no substantial non-semantic content to which truth is applied. This is an anomalous and singular situation. Accordingly, the fact that  is not conservative over an arithmetical base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is interpreted to mean that truth is not conservative over a theory of syntax, but this is not a problem for deflationism, because truth axioms and a theory of syntax always come in one package and it makes little sense to separate and compare them in terms of conservativeness. Even if we somehow separate and compare them, truth is a logico-linguistic device operating on syntactic objects, and thus it would be no surprise anyway that truth adds some syntactic substance to a theory of syntax.Footnote 26 Semantics always comes with syntax, and syntax is not among the non-semantic subject matters on top of which deflationary truth should be conservatively added; non-conservativeness over syntax is not what deflationists would take as a sign of the substantiality of truth.Footnote 27

is not conservative over an arithmetical base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is interpreted to mean that truth is not conservative over a theory of syntax, but this is not a problem for deflationism, because truth axioms and a theory of syntax always come in one package and it makes little sense to separate and compare them in terms of conservativeness. Even if we somehow separate and compare them, truth is a logico-linguistic device operating on syntactic objects, and thus it would be no surprise anyway that truth adds some syntactic substance to a theory of syntax.Footnote 26 Semantics always comes with syntax, and syntax is not among the non-semantic subject matters on top of which deflationary truth should be conservatively added; non-conservativeness over syntax is not what deflationists would take as a sign of the substantiality of truth.Footnote 27

Having reflected upon the fundamental motivation for (Syn) and observed the singularity of theories of truth over arithmetic, I now propose that we should exclude arithmetic (and other ‘poor’ subject matters) from the range of the subject matters to be taken into account in (C1) and we should turn to ‘richer’ subject matters for evaluating the conservativeness argument. Our proponent of the conservativeness argument has no choice but to accept this proposal, since the conservativeness argument based solely on the formal results of theories of truth over arithmetic cannot undermine deflationism: on the one hand, if theories of truth over arithmetic is given with an embedded theory of syntax via coding and syntactic induction entangled with arithmetical induction, then the non-conservativeness of them does not imply the substantiality of truth; on the other hand, if they are formulated with a disentangled theory of syntax and syntactic induction in terms of it, then the conservativeness requirement (C1) is generally met and thus the non-conservativeness claim (C2) simply fails. In contrast to arithmetic, some ‘rich’ subject matters do have substantially rich non-semantic content besides its syntactic content and intrinsically contain a theory of syntax per se; hence, the above argument against the conservativeness argument cannot be generalised to the case where such a ‘rich’ subject matter is taken as the basis of theories of truth. Among others, set theory is a typical example of such a ‘rich’ subject matter: it is often taken as the foundation of mathematics and many would consider some standard theories of sets, such as \(\mathsf {ZF}\), to be maximally rich in the aforementioned sense; also, a theory of syntax per se is regarded as an intrinsic part of set theory, and set theory is rich enough to develop substantial meta-mathematics on the basis of the theory of syntax therein.

Now, let us turn to consider theories of truth over set theory with the assumption of (Syn). Recall that the crucial difference at issue between arithmetic and set theory is that set theory intrinsically contains a theory of syntax and is ‘rich’ enough to implement substantial meta-mathematics on the basis of it. We should proceed with this difference in mind. However, as the aforementioned folklore view goes, a variety of different formulations of the theory of syntax, in terms of finite sequences, trees, natural numbers, and so forth, share essentially the same inductive structure (cf. fn 17), and set theory is rich enough to prove this fact; indeed, we usually need not distinguish different formulations of the theory of syntax in the actual practice of mathematical logic within set theory. Hence, in order to treat theories of truth over arithmetic and set theory in a uniform way, I will assume that the schema of syntactic induction, no matter how it is (reasonably) defined, is equivalent to the schema of arithmetical induction, and, in what follows, I will identify the schema of syntactic induction for \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }^{+}\) with \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) expressed in terms of the standard translation of \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}\) into \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\), where \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\) (\({=} \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {ZF}}\)) is the language of first-order set theory.Footnote 28 Then, in sharp contrast to arithmetical base theories, many theories of truth over sufficiently strong theories of sets, such as \(\mathsf {ZF}\), become conservative even with the addition of \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) (equivalently, the schema of syntactic induction for \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }^{+}\)).

Theorem 1

If \(\mathsf {B}\) is an \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\)-theory extending \(\mathsf {ZF}\), then  is conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\).Footnote 29

is conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\).Footnote 29

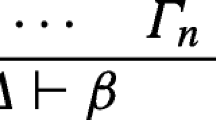

Proof

Suppose  for an \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\)-sentence \(\sigma \). Let \(\mathsf {U}\) be the collection of the axioms of \(\mathsf {B}\) used in the derivation of \(\sigma \). By the Montague-Lévy reflection principle, \(\mathsf {B}\) proves that there exists an admissible set X such that X contains the set of natural numbers (\({=} \omega \)), and

for an \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\)-sentence \(\sigma \). Let \(\mathsf {U}\) be the collection of the axioms of \(\mathsf {B}\) used in the derivation of \(\sigma \). By the Montague-Lévy reflection principle, \(\mathsf {B}\) proves that there exists an admissible set X such that X contains the set of natural numbers (\({=} \omega \)), and

Since X is admissible, we can define the truth class (or the full satisfaction class) of X and interpret the truth predicate \( T \) (or the satisfaction predicate \( Sat \)) thereby. Furthermore, the transitivity of X and \(\omega \in X\) automatically verify \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) under this interpretation. Hence, if \(\lnot \sigma \) were the case, the deduction of \(\sigma \) in  could be modeled in X and thus X would satisfy both \(\sigma \) and \(\lnot \sigma \), which is impossible. \(\square \)

could be modeled in X and thus X would satisfy both \(\sigma \) and \(\lnot \sigma \), which is impossible. \(\square \)

We have the same phenomenon even with a relatively weak subject matter, second-order arithmetic, although it is debatable whether second-order arithmetic is ‘rich’ enough in the sense at issue. Let \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\) denote the theory of full analysis (\({=} \Pi ^{1}_{\infty } \text {-} \mathsf {CA}\), see Simpson 2009) over the language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{2}\) of second-order arithmetic. Then, the following holdsFootnote 30:

Theorem 2

If \(\mathsf {B}\) is an \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{2}\)-theory extending \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\), then  is conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\).

is conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\).

These theorems tell us that, when the non-semantic content of a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is ‘rich’ enough, the extension of syntactic induction to \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+}\) does not add any non-semantic substance.Footnote 31 They also validate my claim in Sect. 4.2 that Cieśliński’s argument only applies to arithmetic; for, if \(\mathsf {B}\) is as in Theorems 1 or 2, then  proves Cieśliński’s principle \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} }\). Furthermore, the same conservation result holds for many other axiomatic theories of truth, including most (if not all) of the so far presented theories of self-applicable truth, over any base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) satisfying the condition of Theorems 1 or 2.Footnote 32 That is to say, we can conservatively add even type-free self-applicable truth to these base theories together with the full schema of syntactic induction. Hence, if we adopt those ‘rich’ bases, we need not give up either blind deduction nor self-applicability as the logico-linguistic functions of truth.Footnote 33

proves Cieśliński’s principle \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} }\). Furthermore, the same conservation result holds for many other axiomatic theories of truth, including most (if not all) of the so far presented theories of self-applicable truth, over any base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) satisfying the condition of Theorems 1 or 2.Footnote 32 That is to say, we can conservatively add even type-free self-applicable truth to these base theories together with the full schema of syntactic induction. Hence, if we adopt those ‘rich’ bases, we need not give up either blind deduction nor self-applicability as the logico-linguistic functions of truth.Footnote 33

Let us summarise the points I have made. First, by Field’s theses (F1) and (F2), any mathematical axiom schemata of \(\mathsf {ZF}\) or \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\) postulated by virtue of its subject matter, such as the collection schema of \(\mathsf {ZF}\) and the comprehension schema of \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\), need not be extended to \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }^{+}\) or \(( \mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{2} )^{+}\) in order to obtain an adequate deflationary theory of truth; only syntactic (arithmetical, equivalently) induction is required to be extended because of its indefinite extensibility as a constitutive element of our understanding of the bearers of truth. Second, as I have argued, even if an infinite conjunction expressed in terms of \( T \) is a reflective consequence of \(\mathsf {ZF}\) (or \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\)), the infinite conjunction, such as \( GRef _{\mathsf {ZF}}\) (or \( GRef _{\mathsf {Z}_{2}}\)) and the statement ‘all axioms of \(\mathsf {ZF}\) (or \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\)) are true’, need not be a consequence of an adequate deflationary theory of truth solely on the ground of its being a reflective consequence of \(\mathsf {ZF}\) (or \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\)). As far as I know, there has been presented no argument so far that compels deflationists to accept the extension of those mathematical axiom schemata or the provability of these infinite conjunctions as necessary part of adequate deflationary theories of truth over \(\mathsf {ZF}\) (or \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\)). Consequently,  and

and  can be (provisionally) seen as adequate theories of truth from the deflationist point of view, but they are still conservative over their base theories. By moving to ‘rich’ base theories, for which the condition (Syn) is appropriately applied, the problems are suddenly dissipated.

can be (provisionally) seen as adequate theories of truth from the deflationist point of view, but they are still conservative over their base theories. By moving to ‘rich’ base theories, for which the condition (Syn) is appropriately applied, the problems are suddenly dissipated.

7 The conservativeness requirement re-examined

In this section, I will consider a possible objection to my proposal, and introduce a new issue into the debate through examination of that objection.

We should not hastily conclude that our deflationist has finally succeeded in refuting the conservativeness argument. As the next proposition shows, not all base theories of even ‘rich’ subject matters enjoy the same strong conservativeness property as \(\mathsf {ZF}\) and \(\mathsf {Z}_{2}\) do.

Proposition 3

Let \(\mathsf {B}\) be either an \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathbb {N}}^{2}\)- or \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\)-theory such that \(\mathsf {B} \subset \mathsf {F} + \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) for some finitely axiomatisable \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\)-theory \(\mathsf {F}\). Then,  proves \( GRef _{\mathsf {B}}\), and thus it is not conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\). The proof is standard and I omit it.

proves \( GRef _{\mathsf {B}}\), and thus it is not conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\). The proof is standard and I omit it.

We have a similar non-conservativeness phenomenon concerning \( T \text {-} \mathrm {Val}_{ \mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} }\), but let us focus on the indefinite extensibility of syntactic induction and its implications, such as \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\), for simplicity.Footnote 34 For example, let \(\mathsf {ZF}_{n}\) (\(n \ge 1\)) be the result of restricting the two axiom schemata of \(\mathsf {ZF}\), i.e., the separation and collection schemata, to the \(\Sigma _{n}\)-formulae in the Lévy hierarchy. It is known that \(\mathsf {ZF}_{n}\) is finitely axiomatisable. Put \(\mathsf {B} = \mathsf {ZF}_{n} + \mathcal {L}_{\in } \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\). This \(\mathsf {B}\) satisfies the condition of Proposition 3. Therefore, it follows that  is not conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\).Footnote 35

is not conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\).Footnote 35

Could one thereby form a new conservativeness argument by appealing to Proposition 3 to the effect that she has found a counterexample, say, \(\mathsf {ZF}_{79} + \mathcal {L}_{\in } \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\), of the conservativeness requirement (C1) and thus truth is substantial? As I will argue below, this non-conservativeness result does not automatically entail the substantiality of truth, and there remain more issues that one would have to discuss and settle before concluding the substantiality of truth.

Firstly, conservativeness is not always required as an adequacy condition for deflationary theories of truth. We have seen in the last section that the conservativeness requirement (C1) should not be applied to theories of truth over arithmetic. Here I will further argue that it need not either be applied to theories of truth over some base theories of even ‘rich’ subject matters. According to the syntactic conservativeness argument, the schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) is required to be part of an adequate theory of truth by our commitment to the indefinite extensibility of syntactic induction. Hence, if there is any other principle derived from the same commitment but expressible in the base language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\), then we are also committed to accepting it regardless of truth. In particular, we are committed to accepting the full induction schema \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) for the base language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\) prior to adding truth to \(\mathsf {B}\). However, it is known that any finitely axiomatisable theory \(\mathsf {B}\) cannot prove \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\) (see Hájek and Pudlak 1993, Lemma 3.47). Hence, any finitely axiomatisable theory \(\mathsf {B}\) fails to fulfill the commitment to the indefinite extensibility of syntactic induction.Footnote 36 This indicates that, if non-conservativeness is a sign of substantiality, the commitment to the indefinite extensibility of syntactic induction is already fairly substantial regardless of truth. And if such commitment is a necessary part of an adequate theory of truth, we have no good reason to require the theory of truth to be conservative over all arbitrary base theories. Furthermore, the syntactic structure of formal languages and our understanding of it might lead us to commit ourselves to some other things of substance, in addition to the indefinite extensibility of syntactic induction, which cause further non-conservativeness results; for instance, constructibility of functions and objects by recursion along \(\omega \) might be considered as such. Therefore, our proponent of the conservativeness argument has to demonstrate that there is indeed a case where (1) truth is still required to be conservatively added to some base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) in spite of the substantiality of the commitment at issue concerning the syntactic structure of formal languages and (2) any adequate theory of truth over that base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is non-conservative. This does not seem to be an easy task. For instance, if a theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is so ‘rich’ as to exhaust all our mathematical commitment concerning the syntactic structure of formal languages and thereby make the commitment negligibly insubstantial, then one may well insist on (1) for such \(\mathsf {B}\), but we have just seen that an allegedly adequate theory of deflationary truth over some natural candidates of such very ‘rich’ theories satisfying (1), such as \(\mathsf {ZF}\), is conservative; now, it is far from clear whether there is indeed any theory \(\mathsf {B}\) that satisfies both (1) and (2).

Secondly, we have to always ask whether the axiomatic approach to truth with the assumption of (Syn) is indeed an appropriate (or necessary) formal setting in a given context. First of all, some other type of theory of truth might be more appropriate than axiomatic theories of truth: if the axiomatic approach is not taken, the conservativeness argument is unlikely to go through (see fn 2). For instance, if one is working within set theory, then the ordinary model theory or some semantic theory of truth might be more appropriate than the axiomatic approach as the theory of truth for, say, second-order arithmetic or real analysis. Next, even when the axiomatic approach is legitimately taken, the condition (Syn) need not be assumed in all cases and one needs to examine whether the assumption of (Syn) is necessary in a given case. I argued that ‘rich’ subject matters essentially need the assumption of (Syn) and this was the reason why we turned to consider theories of truth over set theory. However, when a given subject matter is not ‘rich’ in the sense at issue, our proponent of the conservativeness argument has to somehow demonstrate that (Syn) is still an appropriate and necessary assumption for theories of truth over that subject matter.Footnote 37 Third, even if the subject matter in question is ‘rich’, a given base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) may not fully capture the relevant content of the subject matter and sufficiently represent the ‘richness’ of it. For instance, the mere fact that the language \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathsf {B}}\) of a base theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is the language \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\) of set theory does not necessarily mean that \(\mathsf {B}\) fully captures the relevant content of set theory; the \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\)-theory \(\mathsf {ZF}\) is the most natural and standard axiomatisation of set theory, and it presumably fully captures all the relevant content of set theory at issue, but we can make up an \(\mathcal {L}_{\in }\)-theory that is so weak or unnatural that we can’t even take it to be a theory of sets. Here is an important difference between our new formal setting and the older customary setting in which only arithmetical base theories are considered: in the older setting, the most natural and standard (and even ‘complete’ according to Isaacson 1987) axiomatisation \(\mathsf {PA}\) of arithmetic makes some allegedly adequate deflationary theories of truth non-conservative; by contrast, in our new setting, the same theories of truth over the standard theory \(\mathsf {ZF}\) of sets are conservative; therefore, proponents of the conservativeness argument now have to search the realm of much less natural non-standard theories of the subject matter in question, such as \(\mathsf {ZF}_{79} + \mathcal {L}_{\in } \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\), for evidence of the substantiality of truth.

All these indicate that the conservativeness requirement (C1) is to be posed only to some limited range of base theories, and let us call such a base theory that falls within the proper scope of (C1) an adequate basis for the conservativeness requirement (‘adequate basis’ for short); note that this notion is relative to what adequacy condition is set for theories of truth (and how it is justified), but let us assume that we are given some fixed such. In other words, we now reject (C3) and replace it by the following:

-

(C4)

Whenever a theory \(\mathsf {B}\) is an adequate basis, any adequate theory of truth over \(\mathsf {B}\) must be conservative over \(\mathsf {B}\).

An immediate question is: what theories are counted as adequate bases? Presumably \(\mathsf {ZF}\) is counted as such, but it is highly questionable whether the same can be said of \(\mathsf {ZF}_{79} + \mathcal {L}_{\in }^{+} \text {-} \mathrm {Ind}\). Our proponent of the conservativeness argument needs to give a non-ad hoc answer to this question in such a way that at least one adequate basis \(\mathsf {B}\) makes truth non-conservative. The burden of proof is now on the proponent, and this does not look an easy task.Footnote 38

8 Summary and conclusion

Two versions of the conservativeness argument were presented in Sect. 4,Footnote 39 and we have seen that neither a purely disquotational theory of truth nor a theory of truth with a disentangled theory of syntax provides deflationists with a general solution to the problem raised by them: an adequate deflationary theory of truth should contain the compositional axioms of  , and there are some important cases where the condition (Syn) should be assumed. Then, I argued that the conservativeness argument solely based on the non-conservativeness of (axiomatic) theories of truth (with the assumption of (Syn)) over arithmetic nonetheless fails to undermine deflationism, and thereby concluded that we should turn to consider theories of truth over ‘richer’ subject matters in order to properly evaluate the success (or failure) of the conservativeness argument. However, it turned out that an adequate theory of deflationary truth is conservative over sufficiently strong theories of sets (or second-order arithmetic). This conservation result and the consideration of theories of truth over these ‘richer’ bases in Sect. 7 give a sharper focus to an issue that has not been sufficiently discussed so far: What are adequate bases for the conservativeness requirement? This question also relates the debate on deflationism more deeply and broadly to the philosophy of logic and mathematics, since it involves the following questions: What axioms are needed to fully capture the relevant content of a given subject matter? How should truth be formally implemented in each context? In which case is the axiomatic approach with the assumption of (Syn) appropriately applied and essentially needed? What theory is ‘rich’ enough to make our mathematical commitment concerning the syntactic structure of formal languages negligibly insubstantial? What theories are maximally rich? And so on. There are more factors to be taken into account for the conservativeness argument to go through than philosophers seem to have previously thought, and we haven’t yet reached the stage in which we can make a final verdict on the validity of the conservativeness argument: deflationary theories of truth over ‘rich’ subject matters have not yet been sufficiently explored, and more philosophical and mathematical developments in this area are to be awaited.

, and there are some important cases where the condition (Syn) should be assumed. Then, I argued that the conservativeness argument solely based on the non-conservativeness of (axiomatic) theories of truth (with the assumption of (Syn)) over arithmetic nonetheless fails to undermine deflationism, and thereby concluded that we should turn to consider theories of truth over ‘richer’ subject matters in order to properly evaluate the success (or failure) of the conservativeness argument. However, it turned out that an adequate theory of deflationary truth is conservative over sufficiently strong theories of sets (or second-order arithmetic). This conservation result and the consideration of theories of truth over these ‘richer’ bases in Sect. 7 give a sharper focus to an issue that has not been sufficiently discussed so far: What are adequate bases for the conservativeness requirement? This question also relates the debate on deflationism more deeply and broadly to the philosophy of logic and mathematics, since it involves the following questions: What axioms are needed to fully capture the relevant content of a given subject matter? How should truth be formally implemented in each context? In which case is the axiomatic approach with the assumption of (Syn) appropriately applied and essentially needed? What theory is ‘rich’ enough to make our mathematical commitment concerning the syntactic structure of formal languages negligibly insubstantial? What theories are maximally rich? And so on. There are more factors to be taken into account for the conservativeness argument to go through than philosophers seem to have previously thought, and we haven’t yet reached the stage in which we can make a final verdict on the validity of the conservativeness argument: deflationary theories of truth over ‘rich’ subject matters have not yet been sufficiently explored, and more philosophical and mathematical developments in this area are to be awaited.

Let me finally emphasise again that most philosophical debates on the axiomatic theories of truth have so far been based on formal results about those theories over arithmetic, and this is presumably because philosophers believe that those formal results over arithmetic and their arguments on the basis of them can be generalised to other cases. However, this extrapolation is not valid as I have argued. More generally, theories of truth over arithmetic are often compared and related to second-order arithmetic, but recent research reveals that there are also a number of significant dissimilarities between second-order arithmetic and second-order theories over other bases such as set theory and the theory of real numbers; see Sato (2014, 2015); Schweber (2015) and Hachtman (2017). These formal results indicate that the arithmetical basis shows singular behaviour different from other bases. A primary source of the peculiarity of arithmetic is the \(\Pi ^{1}_{1}\)-completeness of the notion of well-foundedness, and this fact is deeply related to the specific inductive nature of natural numbers in the sense that \(\mathbb {N}({=} \omega )\) is the least infinite ordinal and only contains finite entities, which also plays the crucial role in the proof of Cieśliński’s theorem. All these formal results and considerations seem to support my proposal.

Notes