Abstract

While inclusion, participation and victim-centredness have become catchwords in transitional justice discourse, this rhetoric has not necessarily enabled the articulation of more complex identities and experiences, or the pursuit of varied justice claims. To probe this disconnect, this article engages with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Liberia, a mechanism established to reckon with the country’s history of internal armed conflict, and hailed for its involvement of vulnerable, disenfranchised and oft-overlooked groups. The article combines expressive theories of justice with an innovative corpus-based methodology to critically examine how the Commission made visible, defined and construed these actors through its language of inclusion. Results from word frequency, co-occurrence and sentiment analyses illustrate how the Commission foregrounded the plight and rights of women and children, and their participation as a vehicle for emancipation, but simultaneously reproduced universalist and static identities, fixation on sexual violence and child soldier recruitment, and subject positions lacking in positive or political capabilities. This duality points to inherent tensions in the expressive messaging of TJ institutions, and rather locates the transformative potential of their inclusionary language in the strategic openings it affords for victims’ groups, women and youth organizations in their broader trajectories towards justice and change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A Normative Commitment to Inclusion

The imperative to foreground victims, survivors and disenfranchised groups through inclusionary practices and participatory approaches has become a focal point in the framework of transitional justice (hereinafter ‘TJ’) and neighbouring domains of conflict resolution and peacebuilding (McEvoy & McConnachie, 2013). TJ refers to the full range of processes that societies may adopt to come to terms with the legacies of large-scale human rights violations in the aftermath of violent conflict, authoritarianism or historical injustice, through judicial and non-judicial mechanisms, including prosecution initiatives, truth-seeking, reparation programs, and guarantees of non-recurrence (UNSG, 2004). When committed to inclusion, the establishment of these mechanisms generates opportunities for addressing and reversing dynamics of exclusion and marginalization that underpinned harms and rights violations (Méndez, 2016). Inclusion is also central to the expressive functions and objectives of TJ. Through promises and practices of inclusivity, TJ institutions acknowledge the rights, experiences and needs of those affected by conflict, endorse democratic ideals, and symbolize the state’s responsiveness towards individuals and groups ‘who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized from decision-making processes, such as women, youth, people with disabilities, and members of minority groups’ (van der Merwe & Masiko, 2020, p. 4).

Critical scholars, however, call into question to what extent TJ’s inclusionary declarations and policies have actually addressed deep-rooted asymmetries in access, voice, knowledge creation and power. In most TJ settings, (inter)national policy-makers, experts and institutions control the discursive and epistemic environment—including who gets to speak and act, on what grounds and on which issues—thereby demarcating the contours of inclusion and its boundaries, omissions and hierarchies (Madlingozi, 2010; Selim, 2017). The inclusion of women or youth, for example, has often followed a tokenist ‘add and stir’ approach, and some authors contend that the presence of victims and disenfranchised actors has largely been instrumentalized to legitimize state-driven or elite justice perspectives and practices (Björkdahl & Mannergren Selimovic, 2014; Robins, 2017). While inclusion, participation and victim-centredness have become catchwords in policy statements by international organizations and the mandates governing tribunals, truth commissions and reparation schemes, this discourse has not necessarily opened up space for the articulation of complex and context-bound experiences, priorities and realities, or the pursuit of varied justice claims.

Throughout this article, I trace this disconnect to inherent tensions in the expressive intentionality and messaging of TJ institutions—by pinpointing incongruencies between the promotion of inclusion as a vehicle for emancipation and democratization, and the implicit discursive representation of disenfranchised and conflict-affected actors ‘included’ in the language of these institutions. I scrutinize these dynamics through a critical corpus-based discourse analysis of the Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (hereinafter ‘TRCL’). Established to reckon with Liberia’s history of violence and the civil wars that ravaged the country, the TRCL was commended for its exploration of the impact of conflict on women, youths, children, diaspora and other oft-overlooked groups and for promoting their ownership of the truth-seeking process (Pillay, 2009; Sowa, 2010). The Commission also maintained a sizeable record of its operations on a dedicated website, offering a window into the priorities, principles and power dynamics that governed its policies and articulations of inclusion, as well as providing an opportunity for illustrating the value of quantitative computational text analysis for exploring increasingly available digital TJ records and archives (see Kostovicova et al., 2022).

Using word frequency, co-occurrence and sentiment analyses, I investigate how women and children—as primary targets of inclusion—are foregrounded and constructed in the language of the TRCL, by studying the form and frequency of their semantic presence, the close context in which they are embedded, and the emotional valence of their surrounding text. The results of these linguistic analyses are connected to the wider socio-political and ideological foundations of the Liberian TJ process, in order to assess the expressive potential and limitations of the Commission’s language in advancing the transformative potential of inclusion. How and to what extent has this language enabled—or conversely constrained—the acknowledgement of diverse (post-)conflict experiences and identities, the subversion of harmful social norms and stereotypes, and the active pursuit of justice claims by disenfranchised and conflict-affected individuals as protagonists in TJ processes? And what do these findings tell us about the perspectives and priorities that inform TJ institutions’ approach to inclusion?

The article proceeds by conceptualizing inclusion as part of the expressive function of TJ mechanisms, and of Truth Commissions specifically, while arguing for the utility of a critical corpus-based approach to probe and evaluate this expressive function empirically. Dedicated sections then contextualize the operations of the TRCL and outline the process of collecting and quantifying a specialized corpus of nearly 300 TRCL texts, containing over one million words. The linguistic analyses illustrate how the TRCL foregrounded the plight and rights of women and children, the linkages between conflict realities and historical identity-related marginalization, the lasting impact of social harms and the need for developmental measures of redress, but simultaneously reproduced universalist and static identities, fixation on sexual violence and child soldier recruitment, as well as subject positions lacking in positive or political capabilities. The discussion and conclusion reflect on the duality of these findings and their implications for expressivist theorizing, and suggest further avenues for research using the corpus-based approach.

The Expressive Functions of Inclusion

The global diffusion and institutionalization of the human rights framework, in tandem with decades of civil society and grassroots mobilization, have placed victims at the centre of post-conflict justice mechanisms (Bonacker, Oettler and Safferling, 2013). Increased recognition of different types of violations and their interaction with pre-existing conditions of marginalization, spurred a further move towards the inclusion of diverse categories of conflict-affected groups at various levels and stages of these mechanisms (van der Merwe & Masiko, 2020). Their presence may expand knowledge about the causes, context and consequences of rights violations, and foreground perspectives, priorities and demands that can pave the way for more responsive measures of redress and reform, offsetting top-down justice frameworks (McEvoy & McConnachie, 2013; Méndez, 2016). But beyond increasing the legitimacy and efficacy of TJ processes, meaningful inclusion should also contribute to altering long-standing asymmetries in voice, access and power that delimit the capacity of conflict-affected and disenfranchised actors to exercise their agency as rightsholders and citizens (Bundschuh, 2015; Robins, 2017). As I will argue below, the expressive dimensions of inclusion play a pertinent role in this regard.

Truth Commissions have traditionally claimed to be victim-centric, since their work fundamentally relies on the presence and testimonies of victims as main source of truth. This delimited form of inclusion, however, gradually expanded towards more comprehensive attention for the representation, consultation and participation of diverse sectors in society in the mandates governing these bodies, in their operations, and in the implementation and monitoring of their recommendations. Truth Commissions are state-sanctioned bodies with an official mandate to determine the causes, factual circumstances and consequences of past human rights violations. They establish facts and figures through statement taking, private and public hearings, archival research and forensic examinations. Through their findings and recommendations, Truth Commissions inform institutional and policy reform and may also contribute to prosecutions and reparations. By providing a platform for the stories of victims (and perpetrators), and the consolidation of these stories into a new national narrative, many Truth Commissions also endeavour to encourage reconciliation in divided societies (Hayner, 2011; Bakiner, 2014; Skaar, Wiebelhaus-Brahm and Garcia-Godos, 2022).

Beyond their direct objectives, these Commissions—like other TJ bodies—also serve important expressive and communicative goals (Glasius, 2015; Ottendörfer, 2019; Sander, 2019). Their establishment sends a message to society that the transitional state means to acknowledge and remedy its role in violence, injustice, inequality and exclusion. Expressive theories of justice thus focus on the exemplary importance of the norms and values embodied by these institutions, and their attempts to alter attitudes, behaviours and social conventions by construing and disseminating narratives that engender social cohesion, equality, political trust and a culture of human rights and democracy (De Greiff, 2012; Stahn, 2020). In settings like Liberia, where public hearings and an elaborate outreach campaign were cornerstones of the Commission’s work, and the publication of its report drew ample public attention, these expressive functions are particularly relevant to conceptualizing and understanding the more diffuse and long-term effects of TJ processes. In this vein, I argue that the ubiquitous rhetoric of inclusion features prominently in the expressivist functions ascribed to, and espoused by, Truth Commissions like the TRCL.

First, by foregrounding those who have been harmed and excluded, the state formally acknowledges the suffering of victims and historically marginalized groups and counters denials, rationalizations and untruths circulating in public debate (Hayner, 2011; Murphy, 2017). Second, through recognition of varied abuses and lived experiences, a Commission can validate the legitimacy of grievances put forward by diverse individuals and groups (Allen, 1999). By opening discursive space for these articulations and claims, inclusion can shift the boundaries of what is defined as a crime or harm and which violations merit redress (Destrooper, 2018). Third, the purpose of a Truth Commission is not only to determine what abuses occurred, by whom and to whom, but also to identify and sensitize about the causes, patterns and systematic nature of such abuses. Truth-seeking processes therefore have the potential to dismantle enduring stereotypes, norms and hierarchies that contribute to rights violations (Lemay Langlois, 2018). Through meaningful inclusion, a Commission moreover demonstrates that victims and disenfranchised groups are part of the political community, that they are rightsholders and citizens who can access and make demands of the state (Bakiner, 2014). The participation of these actors as stakeholders and drivers of post-conflict justice processes, creates a new narrative about their role in society, signalling a point of rupture and transformation as the transitional state ‘ritually inverts’ the practices of political, legal and social exclusion that underpinned rights violations (Humphrey, 2003, p. 173).

At the same time, critical voices in victimology and feminist literature have contested the notion that the expressive power of TJ mechanisms is necessarily benign, highlighting instead how their messaging creates categories, hierarchies and subjectivities—grounded in Western, liberal, legalistic notions of justice—that facilitate certain voices and justice narratives whilst silencing others. A well-known critique concerns the flattening and homogenization of diverse experiences and multidimensional identities into ‘an artificially neat moral division’ between dichotomous victim and perpetrator categories (Hourmat, 2015, p. 6). Socially vulnerable groups are typically placed at one end of this moral division, rendering invisible divergent positionalities that violate notions of passivity or blamelessness, including those of female combatants or child soldiers who enrolled voluntarily (Butti & McGonigle Leyh, 2019; Henshaw, 2020). In addition, vulnerability is typically construed around singular and fixed identifiers, such as sex, age or ethnicity, foregoing issues of intersectionality or how the interaction of multiple social identity structures shapes who is disproportionately harmed and who is most likely to gain from TJ arrangements (Jamar, 2021).

This reductivism is exacerbated when conflict-affected individuals are included as emblematic instances of particular harms to which the mechanism wishes to draw attention. These harms, moreover, tend to be narrowly defined and hierarchically structured, as shown by the precedence still given to political and civil rights violations and the hypervisibility of (extreme) forms of bodily violence (Hearty, 2018). Attention for gendered violations, therefore, has often led to a singular focus on sexual violence and the inclusion of women as ‘sexed bodies’ in ‘the framework of rape, victimhood and embodiment’ (Rosser, 2007, p. 398), while other gendered violations and their underlying patriarchal structures of inequality remain insufficiently addressed (Ní Aoláin, 2019). Similarly, where children are included in TJ, focus is typically on the experiences and reintegration of forcibly recruited child soldiers, while stopping short from interrogating the realities that frame these practices, including young people’s economic vulnerability, social subordination and political exclusion (Billingsley, 2018; Butti & McGonigle Leyh, 2019).

These categories and hierarchies give rise to victim subjectivities that are marked by powerlessness and suffering, and that interact with gendered and ageist notions of agency, to portray women, children and other vulnerable actors in conflict as docile, fearful and a-political subjects in need of safety and security, and as beneficiaries of policies and aid (Buckley-Zistel, 2013; Björkdahl & Mannergren Selimovic, 2014). More generally, Truth Commissions typically afford little attention to stories of survival, tactical agency, resistance or resilience, nor to the political motivations that may have framed conflict experiences (Druliolle and Brett, 2018; Renner, 2015). Silence or taboo also shrouds any positive or more complex emotions and memories, including feelings of validation or empowerment found through conflict participation, the resourcefulness of disenfranchised actors, or the subversion of gendered roles during the conflict period (Elston, 2020). These discursive omissions often preclude positive representations of disenfranchised actors as productive, knowledgeable or autonomous change agents. Young people, in particular, are seldom recognized for their ‘creativity and agency […] in enhancing and potentially improving transitional justice processes, practices and outcomes’ (Parrin et al., 2022, p. 1).

As these critiques indicate, it is not sufficient to take the increased visibility of particular people or groups in post-conflict justice processes and discourse as a self-evident marker of success, without interrogating the conditions and characteristics of their visibility (Rosser, 2007). This implies critically probing both the expressive merits and limitations of TJ’s language of inclusion, and how this language may open up discursive sites marked by inclusion as well as exclusion, acknowledgment and omission, subversion of power relations and new inequalities. This is precisely where I locate the utility of critical corpus-based discourse analysis. Critical discourse analysis (hereinafter ‘CDA’) is an interdisciplinary field of discourse study with a strong interest in the representation of social groups and societal issues through language use, and how text and talk can perpetuate, challenge or transform social identities and relations of power and inequality (Wodak, 2009). It allows to for deconstructing TJ discourse as carrier of expressivist meaning, in ways that otherwise remain conceptually underdefined and empirically underexplored. The next section details how the integration of this critical lens with quantitative corpus-based techniques gives rise to a concrete framework and method for analysis.

A critical Corpus-Based Approach

Though a diverse discipline, CDA-inspired studies share a critical drive to unveil what lies below the surface of language use and how discourse—as a social practice—is both conditioned by and constitutive of the social world (Wodak, 2009). According to CDA scholars, language use not only reflects patterns of inequality and injustice, but also reproduces and legitimizes these (Fairclough, 2003). Those who can access and control institutional and public discourse, and thereby influence the socio-cultural beliefs, knowledge and attitudes of recipients, thus exercise a powerful source of hegemony (Van Dijk, 2015). Elucidating these discursive relations and practices requires interconnected levels of analysis, that situate texts against their historical and socio-political background. CDA does not provide one particular method or analytical framework to this end, but rather adopts any method suitable to its aims (Baker et al., 2008). Accordingly, this study takes inspiration from CDA as a ‘way of doing discourse analysis from a critical perspective’ (Ibid, p. 273), unravelling dynamics of power by connecting micro-level patterns in text, to their discursive and social context (Fairclough, 2003).

In practice, CDA studies have predominantly relied on close qualitative analysis of various syntactic, semantic and stylistic features in small text excerpts. But influential authors like Mautner (2009) and Baker et al. (2008) have also argued for fruitful synergies with quantitative corpus-based analysis. Corpus-based methods can arguably offset several core critiques levelled at traditional CDA, including the subjective selection of texts and features for analysis, the questionable reliability of findings derived from small numbers of text fragments, or the limited replicability of the qualitative approach (Widdowson, 2004). Moreover, recent developments in the fields of natural language processing and text mining, as well as the increasing popularity of open source statistical software, have expanded the toolkit available to researchers. These evolutions have spurred pioneering applications of advanced computational text analysis in TJ, peacebuilding and conflict resolution literature (see for example Chlevickaitė, Holá and Bijleveld, 2021; Destrooper, 2018; Kostovicova, 2017; Kostovicova and Phaskalis, 2021; Suárez & Lizama-Mué, 2020). Kostovica et al. (2022, p. 33) underscore the potential of these ‘text as data’ approaches for ‘providing new insights into the content of TJ processes and their effects, and advancing our understanding of the expressive purpose of transitional justice’. This article explicitly aims to contribute to this goal.

Drawing from multiple fields of computational text analysis, the article uses the programming environment R to combine word frequency, co-occurrence and sentiment analysis on a corpus annotated through natural language parsing. These techniques identify repetitive linguistic patterns that signal the discursive strategies of representation at work in the language of the TRCL—as a means for testing the assumptions and critiques foregrounded in the theoretical section. Natural language parsing refers to an automated process that splits running text into individual words which are reduced to their lemma, assigned to a part of speech, and specified in terms of grammatical category and relations. The UDPipe tool carries out this type of annotation based on treebanks from Universal Dependencies and is also available as R package (Straka & Straková, 2017; Wijffels, 2019). Automatic mark-up of the corpus enables an exploration of patterns and variations of pre-defined linguistic features, e.g. to analyse words pre-selected on their part of speech. The analytical section specifies whenever such pre-selection took place.

Following annotation, word frequency lists and permutation testing can validate the semantic presence of women, children and other vulnerable actors in the TRCL’s language, through the form and frequency of relevant actor-referring terms. These referential strategies also speak to dynamics of categorization, assimilation and essentialization, illustrating, for example, whether the TRCL operationalizes inclusion through the abstract usage of genderonyms and gerontonyms, or offers space for more fine-grained considerations of multi-dimensional identities. Second, networks of significant lexical co-occurrences can pinpoint which issues and harms, priorities, needs and interests are recurrently used to contextualize and define these actors, and whether their inclusion catalyses consideration for structural violations and systems of inequality, or remains bound to delimited and embodied harms. A final analysis uses dictionary-based sentiment analysis and Valence Shift Word Graphs to explore the distribution of positively and negatively charged words in texts about women and children. It signals the extent to which these actors remain confined to a suffering past, or are also connected to positive outcomes, and portrayed as capable and productive change agents.

These techniques derive from the work of Dodds and Danforth (2010), Niekler and Wiedemann (2017), Mohammad (2018) and Koplenig (2019) and are detailed in the analysis section. Though the corpus-based approach builds on large amounts of data, quantification and statistics, the step-by-step nature of the analytical process and its interpretation do require ‘manual intervention with intent’ (Potts & Kjær, 2016, p. 534). Quantitative findings can also point to specific fragments that merit a closer qualitative reading, in order to recontextualize words and linguistic features in their natural setting (Mautner, 2009), for example to find meaningful patterns in clusters of words. Working with a specialized corpus, moreover, allows for a close analytical connection ‘between the corpus and the contexts in which the texts in the corpus were produced’ (Koester, 2010, p. 67). Accordingly, the corpus-based approach was complemented with thematic analysis of pertinent secondary sources about the Liberian TJ scene, including academic publications, NGO reports and news articles from Liberian media outlets.

Situating the Liberian Commission

From 1989 to 1996 and from 1999 to 2003, Liberia experienced repeated cycles of internal conflict, claiming over 250.000 lives and displacing a third of the population (TRC of Liberia, 2009). The 2003 Comprehensive Peace Agreement called for the creation of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission and in the TRC Act of 2005, the Commission was mandated to investigate violations and abuses committed between 1979 and 2003, identify main perpetrators, establish the historical root causes of conflict, investigate economic crimes, enable victims and perpetrators to share their experiences, and to compile its findings and recommendations in a public report. Article IV Section 4e of the TRC Act explicitly called for ‘specific mechanisms and procedures to address the experiences of women, children and vulnerable groups, paying particular attention to gender-based violations, as well as to the issue of child soldiers […].’ In the summer of 2006, five male and four female Commissioners commenced their activities, involving outreach, consultation, statement-taking, public hearings, research and report writing.Footnote 1 In parallel, NGO The Advocates for Human Rights engaged with diaspora communities in the US, and to a lesser extent in the UK and Ghana.

Throughout its operations, the TRCL was plagued by a lack of financial resources, adequate logistics or experienced staff, while its reputation suffered from internal strife, political intrigue and the incrimination of three Commissioners. During the public hearing phase, the Commission was criticized for providing an uncritical platform to alleged perpetrators, some of whom received amnesty in exchange for their testimony (James-Allen, Weah and Goodfriend, 2010; de Ycaza, 2013). Despite obstacles and delays, the TRCL submitted its preliminary findings in 2008, followed by the final consolidated report in June 2009 and the edited version with appendices in December 2009. While prominent political figures evaded or outright rejected the findings, the report was met with support by many Liberian citizens over its key recommendations for prosecution and lustration, though international experts expressed doubts over a lack of coherence, evidentiary data and transparency (de Ycaza, 2013; Weah, 2012). The naming of names captured the bulk of public attention, but the TRCL also made recommendations for reparations, memorialization, institutional reform and a traditional truth and reconciliation mechanism (TRC of Liberia, 2009).

The Commissioners stress in their final report how they aspired for the TRCL to be an exercise in inclusion and democratic participation ‘as a way to minimally redress the historical wrong of exclusivity and exclusion’ (TRC of Liberia, 2009, p. 202). This tied into the identification of economic and socio-political inequalities and lack of voice and accountability in governance as core drivers of repeated conflict cycles. Inspired by the Truth Commissions of South Africa and Sierra Leone, the TRCL was to afford particular attention to sections of the population disproportionately or differentially affected by conflict, as a result of long-standing political and socio-economic marginalization. As defined in the TRC Act, these groups were largely subsumed under the banner women, children and (other) vulnerable groups and various efforts were undertaken to stimulate their involvement and visibility in the TRCL process.

Civil society actors from women, youth, disability and other organizations played an important role in development of the TRC Act, selection of Commissioners and in outreach and support efforts. Women were included at all levels of TRC staff, including as Commissioners, managers and statement takers. The Commissioners appointed thematic experts, set up dedicated committees, tailored initiatives of its public outreach campaign to diverse audiences, and took measures to accommodate testimonies of women, children, people with disabilities, the elderly and other groups. Women, youths and children also participated to the hearings and provided inputs for recommendations during workshops, panel discussions, community dialogue meetings or the national Women’s conference. Finally, the TRCL dedicated thematic annexes of its final consolidated report to women, children and people with special needs (Pillay, 2009; TRC of Liberia, 2009; Sowa, 2010; Aptel & Ladisch, 2011). Nonetheless, observers did note important shortcomings such as faltering witness protection and psychological support, lesser coverage of remote areas, and late involvement of gender and child policy expertise (Amnesty International, 2008; James-Allen, Weah and Goodfriend, 2010).

Compiling and Describing the Corpus

The TRCL collaborated with the Georgia Institute of Technology to build an interactive website.Footnote 2 The website provided general information and updates, screened public hearings, boasted an interactive discussion section and allowed for sealed witness statements to be submitted online (Best et al., 2009). Following the termination of TRCL activities, the website now functions as a partial archive of its work, containing the sections about, news, videos, photos, hearings, reports and diaspora. All content and documents are in English. The corpus for this article was built by collecting all relevant, textual materials produced by the TRCL and hosted on its website. Webpages with no analytical relevance (website security, contact page,…) were excluded, as were webpages dedicated to photo and video content. Texts made available or linked to on the TRCL website, but produced by external parties, were also excluded. This applies to various newspaper articles, Benetech’s descriptive statistics report but also the elaborate Diaspora Project report by The Advocates for Human Rights (2009).Footnote 3 Lastly, because duplicate texts can inflate the occurrence of linguistic patterns of interest, identical texts were only retained once and only the edited report versions were included.

Text in html format was collected into R and cleaned with regular expressions, while documents enclosed in MS Word or PDF format were manually cleaned before being passed into the R environment.Footnote 4 In the hearing transcripts, speaker tags were used to demarcate the statements of witnesses. All texts were then annotated with UDPipe, producing a large dataset ready for further analysis. The resulting corpus contains nearly 300 documents, which can be subsumed under three headers or sub-corpora: public hearing transcripts, various news items and the Commission’s reports.Footnote 5 Evidently, it was not possible to access all words ever uttered or written by the TRCL or to sample randomly from this universe. This is a common problem when designing a specialized corpus, which can be addressed by paying attention to situational and linguistic representativeness (Koester, 2010). According to these principles, a corpus of over a million words, reflecting different aspects and stages of the TRCL’s work (hearings, press releases and updates, reports) and including different registers (spoken and written, vernacular and formal) can bring valuable insights into the language use of the TRCL and the discourses present therein.Footnote 6

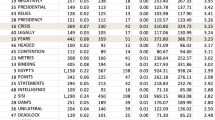

As Table 1 shows, the sub-corpora vary in size, composition, average document length, lexical richness and in their context of production. While complicating a straightforward use of the corpus as ‘one unit of analysis’, this diversity can also be harnessed to uncover dynamics of (self-) (re-)presentation and intertextuality. The contents of the hearing transcripts, for example, were co-constructed by Commissioners and by witnesses, who spoke in the capacity of victim, perpetrator or victim-perpetrator, or as presenters in the case of the thematic and institutional hearings. These texts provide insights into the stories told by female and (to a far lesser extent) child witnesses ‘included’ within the contours of this formal TJ environment. The News and Reports sub-corpora, in turn, recontextualize and integrate these witness statements into an overarching meta-narrative, enabling a comparison of vulnerable actors’ self-presentation and their re-presentation by the TRCL, i.e. which of their experiences, roles and priorities are accommodated in its discourse(s) and which are filtered out. Moreover, differences in textual characteristics also render particular parts of the corpus more suitable to particular types of analysis—as will be explained in the analytical section.

Before moving to the analyses, some last words on audience and reception. While the website was part of the Commission’s strategy to ensure ‘wide dissemination of its findings and the stimulation of public discourse, such that the truths it establishes become common knowledge’ (Best et al., 2009, p. 3), it is quite difficult to map actual exposure. The website was mainly intended to target international (diaspora) audiences, whereas Liberians domestically could have been exposed to text or speech from this corpus through live attendance to the public hearings, broadcasts on radio and television, TRCL mobile video story-telling units, or excerpts cited in newspaper reporting (Weah, 2012). Still, a population-based survey by Vinck et al. (2011) suggests only a small minority of the general population actively followed aspects of the Commission’s work. It is therefore important to understand the impact of institutional discourse not only in terms of direct exposure, but also more broadly in terms of its contribution to ‘controlling the contours of the political world’, in ‘legitimizing policy’ and ‘sustaining power relations’ (Fairclough, 1989, p. 90).

Linguistic Analyses

Against this background discussion of the case and corpus, the following sections demonstrate the application of three corpus-based methods to locate and quantify recurrent patterns of language use that shape how disenfranchised and conflict-affected actors are positioned in the narratives of the TRCL.

Word Frequency

As a starting point, word frequency lists can be a valuable ‘way in’ to a corpus, for example to explore the linguistic presence or absence of various social actors and the particular ways of naming or referencing them (Potts & Kjær, 2016, p. 532). A frequency list of all nouns, proper nouns and adjectives was manually reviewed to identify the most prevalent actor-referring terms across the corpus and by sub-corpus.Footnote 7 Figure 1 shows that high prevalence actors are commonly grouped or defined according to socio-demographic categories of sex and/or age (man, woman, girl, boy), status before the TRCL (witness, victim), family tie (brother, father, mother), combatant role (soldier, officer, commander, rebel), warring faction (NPFL, LPC) or institutional position (TRC, government, commissioner, president). These referential strategies convey an implicit message about who, and in what capacity, is considered relevant to the work of the TRCL. On first sight, the terms woman and child are remarkably high on this list, confirming the foregrounding of these semantic categories in the language of the TRCL. At the same time, their primacy appears to be driven predominantly by the Reports sub-corpus, which contains thematic annexes dedicated to women and children.

The News sub-corpus is strongly self-referential, emphasizing the mission and deeds of the Commission, while the Transcripts still reference men twice as much as women. Coupled to the prominence of words like soldier, officer or commander, this suggests the hearings remained overall more androcentric. Without disaggregating the speech of different speakers in the Transcripts, however, it is not clear who drives these patterns and how they should be interpreted, especially given the inclusion of many female witnesses as speakers. I therefore compare the presence and referential strategies of male and female witnesses across the Transcripts, based on their witness statements.Footnote 8 Their number and similarity in context and textual characteristics, render these statements well-suited to such comparison. The number of child testimonies available in the Transcripts, on the other hand, is unfortunately too limited for a substantive quantitative analysis. Figure 2 visualizes the number of (adult) witness statements included in the Transcript, per hearing location, and by sex. While female witnesses are present at each hearing location, they remain outnumbered by male witnesses.Footnote 9 Figure 3 shows the distribution of these statements in terms of word length, again split by sex. Male witnesses give longer statements on average (mean: 771 words, median: 500 words) compared to female witnesses (mean: 531 words, median: 314 words).

Witnesses do not only speak about their own experiences, but also reference other actors in their statements. I follow Koplenig’s (2019) approach to permutation testing to identify meaningful differences in the use of eight prevalent actor-referring terms between male and female witnesses (man, child, boy, soldier, woman, brother, girl, sister). First, differences in statement length need to be cancelled out. To this purpose, I compile all female statements and all male statements into two running texts, and split them in equally sized fragments of 500 words.Footnote 10 The frequency of the selected word is tallied per fragment and these values are stored in two variables under the headers male vs female. The observed test statistic is calculated as the difference in mean word frequency between both variables. Subsequently, the values under these two headers are pooled and randomly rearranged in 100.000 permutations to obtain permuted test statistics. The approximate p value stems from the number of permuted test statistics whose absolute value is at least as large as the observed test statistic.Footnote 11 This process is repeated for each of the eight selected words. The observed mean frequencies are visualized in Fig. 4 and the corresponding test statistics and approximate p values are shown in Table 2. To check for robustness, this exercise was repeated with fragments of 300 and 700 words in online Annex 1.

While permutation testing reveals no meaningful differences in the occurrence of terms man, soldier or brother between male and female statements, male witnesses are consistently less likely to reference terms signifying women or children (child, woman, boy, girl, sister). The higher presence of male witnesses, both in terms of numbers and length of speech, coupled to a lower tendency to speak about women and children, helps to explain why the transcripts remain overall more androcentric, despite significant efforts to include women as testifiers. Yet, in absolute numbers, Fig. 4 indicates that female witnesses, too, speak more about male than about other female actors. This might be related to an expectation for hearing witnesses to recount factual, event-based stories and to focus on the identification of (high-level) perpetrators.

Lexical Co-occurrence

Beyond quantifying how often vulnerable actors appear, the aim is to understand how they are constituted contextually by the TRCL, through the common and consistent use of neighbouring words. Co-occurrence lists or networks are a valuable tool to provide insight into such lexical connections. Words are said to co-occur when they both appear in the same text segment or word window and significant pairwise co-occurrences refer to words that appear together with a selected ‘node’ word more than would be expected by chance (Baker et al., 2008, p. 278). Building on the semantic prominence of the terms woman and child, I select these terms as node words and calculate co-occurrences across the Reports and News sub-corpora. The sentence boundary was chosen as word window and only nouns, adjectives and verbs were retained for analysis. The Log Likelihood statistic was used to test the hypothesis of dependence between word pairs, based on (1) the number of sentences containing the node word, (2) sentences containing the co-occurring word, (3) sentences wherein both words appear together, and (4) the total number of sentences in the corpus (Niekler & Wiedemann, 2017). There is no agreed cut-off for the resulting association scores, so the top 30 co-occurrences for both node words are visualized in Fig. 5. Sentences including these co-occurrence pairs were also lifted from the corpus and closely read, in order to support a contextual interpretation and create clusters of semantic meaning.

Network graph of top 30 co-occurrences for node words woman and child according to the Log Likelihood association measure. Edge size represents the strength of the association, circle size represents how many edges connect to this word. Words are clustered by shade and position based on qualitative interpretation of results

The node words woman and child exhibit a strong mutual link and also connect to several common clusters of meaning. In the first place, they are key members of a collection of vulnerable groups that also encompass girl(s), young adult(s) and elderly persons. Given their vulnerability, children in particular should be subject to protection and child-friendly practices and policies. Second, women and children are pivotal in a mission to include, that emphasizes attention to their experience(s) and right(s), and promotes their participation in TJ mechanism(s), by adopting specific measures to accommodate them. Third, women and children are construed as beneficiaries of aid, through words like need, welfare, access and program. Moreover, dedicated agenc(ies) should guard the wellbeing of children, who are left traumatized by their horrific ordeals. A smaller cluster acknowledges women and children as civil society actors, through recurrent mention of women’s organization(s), traditional communities, or the children’s Parliament.

Both women and children are further connected to concrete—though differing—issues and harms. In relation to the term child, their war experiences as soldier or combatant in the armed groups are strongly foregrounded, as is the subsequent need for disarmament, demobilization, rehabilitation, and reintegration (DDRR). But children are also figures around whom stories of more diffuse indirect and social harms were construed, including the disruption of family and community ties or the separation from parents, the high resulting number of street children, and the loss of school(ing) opportunities. Women, in turn, are strongly connected to a cluster of gender-based violations, construing them as targets(s) of sexual violence, rape and crimes against pregnant persons. A smaller cluster of more weakly connected words like role, equal and marriage hint at an investigation of social hierarchies and structures that impact the lives of women and their position in society.

Again, the transcripts provide an opportunity to understand what themes were raised by women themselves during the hearings, and how this aligns with their representation by the TRCL in the News and Reports. Beyond actor-referring terms, the word frequency list for female witness statements also contains many words signifying different types of harms these women experienced or witnessed. After manually grouping relevant words into meaningful themes, Fig. 6 lists the five most occurring words per theme and displays the proportion of female statements wherein each of these words occur. The word rape, for example, occurs in 17% of female witness statements. While this graph shows that sexual violence—and other violations of the body—were pervasive throughout the conflict, other highly prevalent themes include forced displacement, the destruction of homes and properties, as well as vivid descriptions of deprivation.Footnote 12 These themes hint at widespread socio-economic harms, that may have explicitly gendered dimensions and consequences, yet do not figure prominently in the co-occurrence list derived from the Reports and News sub-corpora.

Sentiment Analysis

A final analysis explores how the emotive word use of the TRCL further contributes to the evaluative context wherein women or children appear. To this purpose, I use the NRC-VAD lexicon to assign sentiment scores to corresponding words in the Reports sub-corpus. I chose the NRC-VAD lexicon, among a range of available options, for its lexical richness and fine-grained emotion scores. The valence dimension of this lexicon contains scores between 0 (most negative) and 1 (most positive) for 20.000 common English words—obtained through crowd-sourced annotation using best–worst scaling (Mohammad, 2018).Footnote 13 The noun nightmare, for example, has a very low valence score of 0.005 while the adjective beloved is assigned a very high valence score of 0.969. Though simple, dictionary-based sentiment analysis has proven transparent and robust when applied to longer stretches of text (Dodds & Danforth, 2010). The reports sub-corpus was therefore chosen as most suitable unit of analysis. The thematic annex Women and the Conflict (hereinafter ‘Women’s Annex’), and the annex Children, the Conflict and the TRC Children Agenda (hereinafter ‘Children’s Annex’) constitute long cohesive texts, fully dedicated to these actors, and can be meaningfully compared against other volumes and annexes in the Reports.

A few words were removed from the lexicon to improve the accuracy of the analysis.Footnote 14 After tagging, the mean valence—or sentiment—of the Women’s Annex and the Children’s Annex can be measured and benchmarked against the remaining texts in the Reports sub-corpus. This valence measure is obtained by averaging over all individual emotion word scores in the text or collection of texts.Footnote 15 Figure 7 then shows that the Women’s Annex has a slightly higher (more positive) mean valence score, compared to the rest of the Reports sub-corpus. The Children’s Annex, conversely, has a slightly lower (more negative) mean valence score, compared to all other texts in the Reports. Though modest, these mean differences are substantial enough to warrant further investigation, as shown by the approximate p values in Table 3, obtained by permutating individual word valence scores between pairs of texts. For robustness, I also cross-validated these findings in online Annex 2, by matching the texts against two other well-known general purpose sentiment dictionaries: General Inquirer (Stone & Hunt, 1963) and Bing Liu’s Opinion Lexicon (Hu & Liu, 2004).

Valence Shift Word Graphs are a valuable technique to understand which words actually contribute to these findings, and how. The underlying calculation determines the percentage contribution of each emotion word to the observed difference in mean valence between a reference and comparison text, on the basis of (1) the word’s numerical valence score relative to the reference text average and (2) its change in relative frequency between the reference and comparison text (Dodds & Danforth, 2010). First, the Women’s Annex is set as comparison text and the remainder of the Reports sub-corpus functions as reference. Afterwards, this exercise is repeated with the Children’s Annex as comparison text. The results are visualized in Fig. 8. Bars pointing right contribute to valence increase in the comparison text, through an increase in frequency (upward arrow) of relatively positive emotion words (in dark grey) or a decrease (downward arrow) of relatively negative emotion words (in light grey). Conversely, bars pointing left contribute to valence decrease in the comparison text, either through a higher prevalence of relatively negative emotion words or a lower prevalence of relatively positive emotion words.

Figure 8a shows how the higher valence of the Women’s Annex is mainly caused by a striking loss of negative emotion words that connote conflict participation and violent or criminal agency (armed, crime, criminal, arrest, perpetrator, violation, commit, murder), and by a gain in positive emotion words that denote crucial development needs and goals for improving the lives of women (health, education, equality, school, skill). Interestingly, the positive valence shift in Fig. 7a is therefore driven by things women either did not do or currently do not have. Figure 8b indicates the Children’s Annex’s lower valence is mainly driven by increased association with armed groups (armed, rebel, gun, soldier) and acts or experiences of abuse and suffering (rape, kill, abuse, suffer, vulnerable, killing). This signals that children, in contrast to women, are acknowledged both as victim and violent actor, though neither group is associated with perpetrator-hood (arrest, perpetrator). Interestingly, though, whereas the word peace drives valence increase for the Women’s Annex, its lower prevalence in the Children’s Annex further contributes to the valence decrease observed in Fig. 7b.

Discussion

Rather than considering these micro-level patterns of lexical choices as natural or given, a critical approach examines the intentions and assumptions underlying this language use, as well as the cultural attitudes, social meanings and ideologies that are naturalized through these choices. This section will highlight how findings substantiate critiques made in extant TJ literature, but also what comes out of the analysis that is different, unexpected, or tends to be obscured in conventional qualitative discourse approaches.

Defining the Subjects of Inclusion

As explained in the contextual background, the TRCL built its inclusionary strategy around the notion of vulnerability to rights violations rather than direct victimhood or instances of (physical) victimization. This enables the TRCL to draw attention to the nexus of experiences during periods of conflict and patterns of discrimination and inequality predating and outlasting conflict, breaking open narrow definitions and timelines of harm. The highly prevalent semantic categories of woman and child thus become central subject positions in a narrative of inclusion, around whom conflict experiences and violations are construed, rights and protection are formulated, and measures for redress are proposed. Moreover, where women are afforded discursive space, as in the public hearings, findings show they are more likely than men to also foreground the experiences of (other) women and children, exponentially increasing visibility.

Yet, the referential strategies of the TRCL are not unproblematic, both in their form and frequency. First, the use of generalised nomination strategies on the basis of universal, static identifiers of sex and age can cover up important differences in social and political identities. In the co-occurrence network, the node word woman does not interact with terms referencing social class, ethnicity, religion, ability, sexual orientation or other social identity structures, while children tend to be diversified only by sex or biological age. As noted in the theoretical section, this lack of intersectional understanding can ‘reinforce existing power imbalances that inclusion efforts claim to address’ (Jamar, 2021, p. 285). Other disenfranchised or minority groups are also far less visible in the language of the TRCL, obscuring their pertinence and turning the dyad of women and children into a placeholder or device to signify all vulnerable social identities.

Second, discourse scholars often implicitly assume that powerful institutions produce stable and monolithic discourse(s). Yet, after analysing large amounts of text across different sub-corpora, findings signal the difficulties in mainstreaming inclusionary perspectives and the fragmentary nature of this rhetoric. The primacy of women and children is very evident in the Reports, but less so in the New and Transcripts. Findings show that male witnesses still dominate the public hearings, not only in numbers, but also in their tendency to give longer testimonies, that are more male-centred. The low visibility of words like child or girl in the News sub-corpus, on the other hand, illustrates how children’s issues were not consistently addressed throughout the Commission’s work, or included sufficiently in outreach messages, a view also expressed by the International Centre for Transitional Justice (Aptel & Ladisch, 2011).

Demarcating Issues, Harms and Needs

An important way for institutional actors to exercise discursive power is by selectively drawing attention to specific issues or controlling what topics can be brought forward. In this sense, the co-occurrence network signals a strong fixation by the Commission on sexual violence as the primary gendered harm targeting women. While it is crucial to recognise the pervasive use of sexual violence as weapon of conflict, equal attention should be afforded to the gendered impact and long-term consequences of displacement, deprivation and destruction on women’s socio-economic rights, needs and agency, given the prevalence of these themes across their testimonies, and the likelihood for these harms to exacerbate pre-existing cleavages in access to property, livelihood opportunities, health and education services (Ní Aoláin, 2019). Moreover, Liberian women who participated to community dialogue meetings towards the end of the TRCL’s timeline, ‘were more concerned about reparations and compensation for lost homes, livelihood, education for their children and security from the perpetrators that they were living with in their communities’ (Pillay et al., 2010, p. 91–92).

The co-occurrence network further points towards a tendency to equate gender sensitivity to the promotion of a women’s agenda and the participation of women and girls, whereby gender is equated to women, and women are cast opposite to men. Other authors have noted that sexual abuse against men and boys was not connected to gender-based violence by the TRCL, the experiences of LGBTQI + groups were ignored, and gender was not applied as analytical tool for understanding conflict dynamics (James-Allen, Weah and Goodfriend, 2010). Through the involvement of a gender expert towards the end of its operations, the Commission’s final consolidated report did foreground the pursuit of gender equality more explicitly, and formulated recommendations responsive to women’s developmental demands (Pillay, 2009), traces of which can be seen in the co-occurrence network and in Fig. 8a.

When it comes to children and youths, the Commission’s extensive attention to the thematic of child soldiers was mediated through a dominant focus on young people’s immaturity or impressionability and their need to be protected or saved through child-friendly policies, programs and agencies. This narrative does not necessarily align with former child soldiers’ self-identification and views, and largely erases their tactical agency or desires for social and economic empowerment (Butti & McGonigle Leyh, 2019). On the other hand, the TRCL’s focus on children and young people also invited attention to social dimensions of harm that reflect ongoing damage to ‘human relationships and connectedness’ and which are often said to be side-lined by TJ initiatives (Sankey, 2016, p. 9), including the breakdown of social, community and family structures and ties, and the high resulting number of minors living in the streets. Attention to the loss of educational opportunities and the strong desire for schooling as avenue to improved livelihoods, moreover, aligns with the emergence of education as top priority in the above-mentioned survey by Vinck et al. (2011).

Assigning Roles, Behaviours and Subjectivities

Beyond emphasis on particular topics or issues, the language of the TRCL carries more diffuse messages concerning the roles, behaviours and subjectivities of conflict-affected groups in post-conflict Liberia. In line with critiques offered in the literature review, the analysis points to an aura of vulnerability that surrounds disenfranchised groups as persistent and immutable property. Throughout the News and Reports, recurrent lexical patterns paint women and children as subjects of harm, targets for inclusion and beneficiaries of aid, while it is less about what they do, cause, choose or produce. While women and children are connected by their vulnerability, comparing and contrasting the quantitative findings also revealed more intricate nuances in the diverging dual portrayal of women as victims/peacebuilders on the one hand, and of children as victims/combatants on the other hand.

These differences in portrayal are evident, for example, in the scant reference (both in the co-occurrence network and sentiment analysis) to women and girls in combatant or auxiliary roles and their motivations for supporting the fighting forces. This obscures the full spectrum of their realities and strategies in conflict (see Specht, 2007), but also means they are likely to miss out on the benefits of demobilization and reintegration programs, deepening cleavages with their male counterparts (Henshaw, 2020). On the other hand, connections to women’s organizations in the co-occurrence network and the positive association with peace processes in the sentiment analysis, do signal an acknowledgment of the organizing and mobilizing capacity of civilian women, notably their grassroots activism surrounding the peace accord negotiations or proactive organization of community dialogue meetings in the context of the TRCL (Pillay et al., 2010).

When it comes to children and young people, by contrast, both their victimhood and their participation to the armed conflict received extensive attention, exemplifying their dual role as victims and as foot soldiers in violence. Yet, by casting them as traumatized and impaired, the TRCL risks to obscure their resilience and may raise doubt over their capacity to actively participate or make autonomous choices in the post-reconstruction of their lives and communities (Billingsley, 2018; García Gómez, 2021). As the sentiment analysis vividly showed, a thorough exploration of the positive role children, youths and young adults can play in driving political change or peace processes is strikingly absent. In this sense, those identified as vulnerable are too often assumed incapable of protecting their own interests or transforming their own situation, perpetuating fixed identities and entrenching power asymmetries between those who risk being harmed and those who are supposed to protect and intervene on their behalf (Gilson, 2016).

Limitations

It is important to point out several limitations to the corpus-based approach, and of this study in particular. The choice for prior mark-up of the corpus precludes a more inductive approach (associated with the corpus-driven method), where ‘linguistic constructs themselves emerge from analysis of a corpus’, and that may have produced additional, diverging or unexpected results (Biber, 2012, p. 159). Second, the automated annotation process is not flawless. While the UDPipe tool attains a parsing accuracy of over 90% for the English language (Straka & Straková, 2017), this percentage may be affected by the complex sentence structures, unusual vocabulary, grammar and spelling errors found in the TRCL corpus. More fundamentally, a quantitative discussion of the corpus inevitably reiterates particular linguistic devices that are precisely the object of critique, such as the value-laden term vulnerable groups, the repeated co-referencing of women and children or the binary constructions of gender through the juxtaposition of man/woman or boy/girl. The choice for a macro-reading of the corpus, rather than a micro-analysis of selected testimonies, may also inadvertently gloss over the multiplicity of voices present in the corpus. This ties into a more general criticism of CDA scholars’ tendency to study the unilateral influence of the discourses of the powerful, while neglecting ongoing discursive struggles and the counter-narratives of those defying this hegemony (Souto-Manning, 2014). Nor did the study measure the actual impact of the TRCL’s expressive messaging on the ground, which would be an interesting and necessary focus for future research.

Conclusion

In Liberia, as in many post-conflict settings, resistance by powerful TJ opponents has dampened the prospects for accountability and redress, placing the burden with ‘the increasing number of civil society organizations, victims’ groups and women’s groups advocating for the implementation of the TRC’s recommendations’ (Weah, 2012, p. 342). Over the years, these groups have repeatedly mobilized and marched to demand accountability, efforts that gained new momentum in light of the Liberian Senate’s recommendation for a Transitional Justice Commission and several universal jurisdiction trials abroad (Liberian Observer, 2021; The Analyst, 2021). This article adopted a critical corpus-based approach to investigate how and to what extent the TRCL’s expressive commitment to inclusive justice, created openings or constraints for these and other disenfranchised and conflict-affected actors to voice their experiences and interests, subvert norms and systems that engender inequality, and assert themselves as protagonists in post-conflict change processes. In this way, the article moved beyond normative theorizing about expressive ideals, or the use of conventional qualitative discourse approaches to criticize TJ’s expressive power, to produce more comprehensive and nuanced insights.

Findings show, on the one hand, how the explicit foregrounding of vulnerable actors in the TRCL’s language has given weight to their experiences and grievances, asserted their right to remedy, and legitimized their participation to institutional spaces of policy-making. The TRCL’s attention to differential conflict experiences the interconnection with historical identity-related marginalization, the recognition of social harms and emphasis on developmental aspects of redress can place these issues higher on the agenda and impact political opportunity structures. Yet, the Commission has also reproduced categories, hierarchies and subjectivities that may preclude individuals from using their visibility on the TJ stage to overcome their vulnerability: (1) the resort to generalist and static identifiers and identities that downplay intersectionality, complex (gendered) conflict experiences and multi-layered roles; (2) the prioritization of conflict-related sexual violence and forced recruitment over other harms, which may cast priorities and demands that diverge from these particular violations as excessive or illegitimate; and (3) the construal of subject positions marked by a need for care, aid and protection, while backgrounding actors’ own productive capacities, political subjectivities and expertise.

This duality has practical consequences, as well as implications for expressive theorizing. When the TRCL urges women, children and (other) vulnerable groups to become visible and engaged in its processes, they are implicitly encouraged and expected to ‘understand, identify and represent themselves’ according to the delimited discursive subject positions construed by the Commission (Druliolle and Brett, 2018, p. 5). In rejecting or transgressing these positions, they may be ostracized from the TJ process, or forego the claim to rights, entitlements or benefits (Buckley-Zistel, 2013). An inherent tension then arises, whereby the TRCL increases the visibility of vulnerable groups to express the transitional state’s commitment to equal rights, social integration and democratization, while simultaneously failing to fully acknowledge their justice perceptions and needs, or the transformative roles these actors may take up in the post-conflict context as a crucial component to (re)establishing their citizenship. Consequently, the emancipatory potential of TJ’s language of inclusion may rather lie in the way victims’ groups, women and youth organizations strategically harness and transpose the expressive openings afforded by this language, to pursue their voice, rights and interests across multiple moments and spaces that make up their broader trajectory towards justice and change.

The corpus-based approach offers a plethora of avenues for exploring this assertion, and for studying the ways in which conflict-affected and disenfranchised groups in post-conflict societies are impacted by, and in turn interact with, the ubiquitous rhetoric of inclusion and participation. Combining corpus-based and in-depth qualitative methods can provide insights into more intricate dynamics of discursive reception, uptake, negotiation or resistance. Building larger and more diverse corpora across different cases and across time would, moreover, allow researchers to study variation and change, as well as apply more sophisticated machine learning approaches, such as word embeddings or the use of predictive modelling. Corpus-based methods are also well-suited to understand to what extent mass media appropriate and further disseminate TJ discourse, and the consequences thereof. This article only started to scratch the surface of what critical corpus-based analysis has to offer for enhancing the evidence base of TJ, but opened several avenues for further theorization as well as methodological innovation.

Notes

Prosecution of former Liberian president Charles Taylor before the Special Court for Sierra Leone partly coincided with the timeframe of the TRCL.

While diaspora involvement was a highly innovative part of the TRCL’s strategy, it is not clear to what extent the Commission actively shaped, guided or revised the content and language of this report.

Cover pages, content tables, abbreviation lists, headers and footers, dividing pages, tables with non-running text, pictures, graphs and acknowledgements were manually removed. Website navigation and speaker tags were cleaned from html text.

Transcripts of in-camera hearings, public hearings in Margibi and Grand Cape Mount counties, and institutional/thematic/window case hearings at the Centennial Pavilion were not made available. Volume 4 of the Commission’s Reports remains unpublished, and was supposed to aggregate all transcripts.

Nevertheless, some situations or instances are missing, for example the language used during statement taking in the field or the text and speech used in the public outreach campaign.

This and subsequent analyses are based on the (decapitalized) lemma, so inflected word forms can be analysed as one item.

To improve comparability and interpretability, these analyses focus on the initial statement given by each witness, but not the subsequent Q&A with Commissioners. Presenters from the institutional or thematic hearings were not included. Their presentations varied excessively in style, length and in the way they were transcribed.

Koplenig (2019) demonstrates the approach using 500 word fragments. For this article, 500 word fragments were also deemed suitable, as this approximates the average witness statement length (mean: 686 words/median: 413 words).

Calculation includes the actual sample in numerator and denominator. For clarity, the approximate p values are reported instead of their binomial confidence intervals.

Importantly, a few additional female witnesses referenced sexual violence without explicit resort to the terms shown in the graph, for example by recounting how they were taken as ‘wife’ by soldiers, indicating both abduction and sexual abuse/slavery.

More details about the construction of the lexicon are discussed in online Apendix 2.

Woman, child and related identifiers man, girl, boy, gender, adult, young, old. High frequency (stop)words be, have, will, do, take, must, other, person, human, government, country, commission, media, company, war, violence, grand, united.

Words without sentiment score play no further role in the analysis.

References

Allen, J. (1999). Balancing justice and social unity: Political theory and the idea of a truth and reconciliation commission. University of Toronto Law Journal, 49(3), 315–354.

Amnesty International (2008) Liberia: Towards the final phase of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/AFR34/002/2008/en/ (accessed 15 September 2021).

Aptel, C and Ladisch, V. (2011) Through a New Lens: A Child-Sensitive Approach to Transitional Justice, International Affairs. New York and Brussels: International Center for Transitional Justice.

Baker, P., et al. (2008). A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse & Society, 19(3), 273–306.

Bakiner, O. (2014). Truth commission impact: An assessment of how commissions influence politics and society. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 8(1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijt025

Best, M. L. et al. (2009) Designing for and with diaspora: A case study of work for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of liberia. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Boston, pp. 2903–2917.

Biber, D. (2012). Corpus-based and corpus-driven analyses of language variation and use. In B. Heine & H. Narrog (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis (pp. 159–192). Oxford Academic.

Billingsley, K. (2018). Intersectionality as locality: Children and transitional justice in Nepal. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 12(1), 64–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijx032

Björkdahl, A., & Mannergren Selimovic, J. (2014). Gendered justice gaps in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Human Rights Review, 15(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-013-0286-y

Buckley-Zistel, S. (2013). Redressing sexual violence in transitional justice and the labelling of women as “victims". In T. Bonacker & C. Safferling (Eds.), Victims of International Crimes: An Interdisciplinary Discourse (pp. 91–100). Asser Press.

Bundschuh, T. (2015). Enabling transitional justice, restoring capabilities: The imperative of participation and normative integrity. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 9(1), 10–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/iju030

Butti, E., & McGonigle Leyh, B. (2019). Intersectionality and transformative reparations: The case of Colombian marginal youths. International Criminal Law Review, 19(5), 753–782. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718123-01906002

Chlevickaitė, G., Holá, B., & Bijleveld, C. (2021). Suspicious minds? Empirical analysis of insider witness assessments at the ICTY, ICTR and ICC. European Journal of Criminology, 58, 89–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370821997343

De Greiff, P. (2012). Theorizing transitional justice. Nomos, 51(2012), 31–77.

Destrooper, T. (2018). The stories we tell victims: Victim participation and outreach programs at the extraordinary chambers in the courts of Cambodia. International Journal of Legal Discourse, 3(1), 103–131. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijld-2018-2005

Dodds, P. S., & Danforth, C. M. (2010). Measuring the happiness of large-scale written expression: Songs, blogs, and presidents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(4), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9150-9

Druliolle, V., & Brett, R. (Eds.). (2018). The politics of victimhood in post-conflict societies: Comparative and analytical perspectives. Springer.

de Ycaza, C. (2013). A search for truth: A critical analysis of the liberian truth and reconciliation commission. Human Rights Review, 14(3), 189–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12142-013-0268-0

Elston, C. (2020). Nunca invisibles: Insurgent memory and self-representation by female ex-combatants in Colombia. Wasafiri, 35(4), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2020.1800254

Fairclough, N. (1989). Language and power. Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge.

García Gómez, D. C. (2021). “I Have the Right”: Examining the role of children in the #DimeLaVerdad Campaign. In J. M. Beier & J. Tabak (Eds.), Childhoods in Peace and Conflict (pp. 65–84). Palgrave MacMillan.

Gilson, E. C. (2016). Vulnerability and victimization: Rethinking key concepts in feminist discourses on sexual violence. Signs, 42(1), 71–98. https://doi.org/10.1086/686753

Glasius, M. (2015). It sends a message: Liberian opinion leaders’ responses to the trial of Charles Taylor. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 13(3), 419–447. https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqv023

Hayner, P. (2011). Unspeakable truths : Transitional justice and the challenge of truth commissions (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Hearty, K. (2018). ‘Victims of human rights abuses in transitional justice: Hierarchies, perpetrators and the struggle for peace. International Journal of Human Rights, 22(7), 888–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2018.1485656

Henshaw, A. L. (2020). Female combatants in postconflict processes: Understanding the roots of exclusion. Journal of Global Security Studies, 5(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz050

Hourmat, M. A. G. A. (2015) A critique of transitional justice and the victim-perpetrator dichotomy: the case study of Rwanda. PhD Thesis, University of Coimbra, Portugal.

Hu, M. and Liu, B. (2004) ‘Mining and summarizing customer reviews. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Seattle, pp. 168–177.

Humphrey, M. (2003). From victim to victimhood: Truth commissions and trials as rituals of political transition and individual healing. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 14(2), 171–187.

Jamar, A. (2021). The exclusivity of inclusion: Global construction of vulnerable and apolitical victimhood in peace agreements. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 15(2), 284–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijab014

James-Allen, P., Weah, A. and Goodfriend, L. (2010) Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Transitional Justice Options in Liberia. New York and Monrovia: International Center for Transitional Justice.

Jockers, M. L. and Thalken, R. (2020) Text Analysis with R. Springer International Publishing.

Koester, A. (2010). Building small specialised corpora. In A. O’Keeffe & M. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics (pp. 66–79). Routledge.

Koplenig, A. (2019). A non-parametric significance test to compare corpora. PLoS ONE, 14(9), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222703

Kostovicova, D. (2017). Seeking justice in a divided region: Text analysis of regional civil society deliberations in the Balkans. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 11(1), 154–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijw023

Kostovicova, D., Kerr, R., Sokolić, I., Fairey, T., Redwood, H., & Subotić, J. (2022). The “digital turn” in transitional justice research: Evaluating image and text as data in the Western Balkans. Comparative Southeast European Studies, 70(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2021-0055

Kostovicova, D., & Paskhalis, T. (2021). Gender, justice and deliberation: Why women don’t influence peacemaking. International Studies Quarterly, 65(2), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab003

Lemay Langlois, L. (2018). Gender perspective in UN framework for peace processes and transitional justice: The need for a clearer and more inclusive notion of gender. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 12(1), 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijx034

Liberian Observer (2021) 'Pres Weah assures due consideration to Senate’s TRC/TJC recommendations', 16 August. https://www.liberianobserver.com/pres-weah-assures-due-consideration-senates-trctjc-recommendations (accessed 15 September 2021).

Madlingozi, T. (2010). On transitional justice entrepreneurs and the production of victims. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 2(2), 208–228.

Mautner, G. (2009). Corpora and critical discourse analysis. In P. Baker (Ed.), Contemporary Corpus Linguistics (pp. 32–46). Continuum.

McEvoy, K., & McConnachie, K. (2013). Victims and transitional justice: Voice, agency and blame. Social and Legal Studies, 22(4), 489–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663913499062

Mohammad, S. M. (2018) Obtaining reliable human ratings of valence, arousal, and dominance for 20,000 English words. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Melbourne, pp. 174–184.

Murphy, C. (2017). The Conceptual Foundations of Transitional Justice. Cambridge University Press.

Méndez, J. E. (2016). Victims as protagonists in transitional justice. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 10(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijv037

Niekler, A. and Wiedemann, G. (2017) ‘Hands-on: A Five day text mining course for humanists and social scientists in R. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Teaching NLP for Digital Humanities. Berlin, pp. 57–65.

Ní Aoláin, F. (2019). Transformative gender justice? In P. Gready & S. Robins (Eds.), From Transitional to Transformative Justice (pp. 150–171). Cambridge University Press.

Ottendörfer, E. (2019). Assessing the role of hope in processes of transitional justice: Mobilizing and disciplining victims in Sierra Leone’s truth commission and reparations programme. Globalizations, 16(5), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1558632

Parrin, A., Simpson, G., Altiok, A., & Wamai, N. (2022). Youth and transitional justice. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 16(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijac003

Pillay, A. (2009). Views from the Field: Truth seeking and gender: The liberian experience. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 9(2), 91–99.

Pillay, A., Speare, M., & Scully, P. (2010). Women’s dialogues in post-conflict Liberia. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 5(3), 89–93.

Potts, A., & Kjær, A. L. (2016). Constructing achievement in the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY): A corpus-based critical discourse analysis. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, 29(3), 525–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-015-9440-y

Renner, J. (2015). Producing the subjects of reconciliation: The making of Sierra Leoneans as victims and perpetrators of past human rights violations. Third World Quarterly, 36(6), 1110–1128. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1047197

Robins, S. (2017). Failing victims? The limits of transitional justice in addressing the needs of victims of violations. Human Rights and International Legal Discourse, 11(1), 41–58.