Abstract

The year 1618 was once regarded as a minimum of the first observed solar cycle or even the beginning of the extended Maunder minimum. However, new results from the annual dataset of radiocarbon (Usoskin et al., Astron. Astrophys. 649, A141, 2021) shows that 1620 was the solar minimum, instead of the year 1618. We revisited the sunspot activity in 1618 from historical records of naked-eye sunspot observations (HRNSOs) in China, as daily telescopic observations were found on only 28 days in 1618, and they are far from sufficient to resolve the difference. We rediscovered 23 HRNSOs from 1618 by a search of more than 800 historical books, with 15 HRNSOs identified as independent observations. From the sunspot records rediscovered here, the Chinese had seen several large sunspots in 1618. On 20 and 21 June 1618, the vapor-like sunspots were so large that even ordinary people could see them and thought that the Sun was abnormal. On 22 June 1618, at least three Chinese observers reported a huge group as a diffusive, round, and vapor-like object with an impressive size. The 23 HRNSOs rediscovered here provide valuable observations to determine the sunspot activity in the year 1618. Our result confirms the one from the annual dataset of radiocarbon, and shows that the year 1618 was quite active.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Solar activity in 1618 was once regarded as quite weak. In the group sunspot number (GSN) dataset (Hoyt and Schatten, 1998), the yearly GSN in 1618 is only 1.3 (from NOAA website, www.ngdc.noaa.gov/stp/space-weather/solar-data/solar-indices/sunspot-numbers/group/), and it is the weakest during the period 1610 – 1629. The year 1618 was once considered as the solar minimum of the first observed solar cycle 1610 – 1618 (Vaquero et al., 2011). Further, Vaquero and Trigo (2015) claimed that the year 1618 was the beginning of the extended Maunder minimum. However, Zolotova and Ponyavin (2015) argued that the solar minimum around 1618 was false due to artificial noise in the GSN dataset.

The year 1618 in this article corresponds to AD 1618. From now on, 1618 is AD 1618 in the Gregorian calendar, and when we do not explicitly mention the year, we refer to this particular one.

A recent investigation has redetermined the solar cycle dates for the period 971 – 1900 using the new annual data series of radiocarbon. Different from the earlier results (Hoyt and Schatten, 1998; Vaquero et al., 2011; Vaquero and Trigo, 2015), the new result shows that 1620 is the minimum of the first observed solar cycle, instead of 1618 (Usoskin et al., 2021).

According to the dataset from the NOAA website mentioned above, Scheiner presented seven sunspot drawings in March, while Malapert made overlapping observations with Scheiner and showed nine drawings in June and seven drawings in July. Riccioli claimed that he had never seen a sunspot in 1618, and the claim was obviously wrong, as it contradicts the sunspot drawings in March, June, and July. Among all the sunspot observers in 1618, only Marius reported a reduction of sunspots for 1.5 years. However, getting daily sunspot observations from Marius’s fuzzy report without an exact date is not easy.

Daily sunspot drawings were far from sufficient to confirm the new solar minimum in 1620 (Usoskin et al., 2021). At present, sunspot drawings are found on only 28 days in AD 1618 (Hoyt and Schatten, 1998; Neuhäuser and Neuhäuser, 2016). Sunspot observations in 1618 need a careful reanalysis and investigation to solve the discrepancy (Usoskin et al., 2021).

We found 23 historical records of naked-eye sunspot observations (HRNSOs) (Wang and Li, 2019, 2020, 2021) in 1618 by searching more than 800 Chinese historical books in five years (booknamelist220217.txt in the supplementary material provides an incomplete list of the books). We found that some of the 1618 records in the previous catalogues (Beijing Observatory, 1988; Yau and Stephenson, 1988; Xu and Jiang, 1990; Xu, Pankenier, and Jiang, 2000; Hayakawa et al., 2017) were either incomplete, missing, or wrong. The rediscovered records provide rich clues to know the real sunspot activity in 1618. The sunspot details (sizes, distributions, etc.) in the 23 records are discussed here.

2 Overview of HRNSOs in 1618

The HRNSOs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Some Chinese characters are given here in Pinyin (official romanization system for standard mandarin Chinese).

2.1 Sunspot Records at the National Level

The National Astronomical Observatory (NAO) in Beijing had made daily observations of astronomical events for about 500 years since 1422. The NAO was called  in the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) (Brook, 2010) and was renamed

in the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) (Brook, 2010) and was renamed  in the Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911). The NAO was a subsidiary of the Astronomical Bureau (

in the Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911). The NAO was a subsidiary of the Astronomical Bureau ( ). The Astronomical Bureau (AB) was composed of the calendar department, the observation department, the timekeeping department, etc. The NAO was in the observation department.

). The Astronomical Bureau (AB) was composed of the calendar department, the observation department, the timekeeping department, etc. The NAO was in the observation department.

The archives of astronomical observations in the NAO were kept secret, accessible to only a few high-rank officers with permits. The authors of  (Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu),

(Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu),  (Ming-Shi), and

(Ming-Shi), and  (Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian) could read the archives in the NAO. Some sunspot observations from the NAO were recorded in the official history of the whole of China, such as Ming-Shi and Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian.

(Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian) could read the archives in the NAO. Some sunspot observations from the NAO were recorded in the official history of the whole of China, such as Ming-Shi and Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian.

The civilian historians were not allowed to read the archives in the NAO. However, Wenbin Long (the author of  (Ming-Hui-Yao)) was probably allowed to read the archives in the NAO, as he was a high-rank officer. Some sunspot records in Ming-Hui-Yao (read Section 4.4) were likely to be taken from the NAO archives.

(Ming-Hui-Yao)) was probably allowed to read the archives in the NAO, as he was a high-rank officer. Some sunspot records in Ming-Hui-Yao (read Section 4.4) were likely to be taken from the NAO archives.

2.2 Sunspot Records at the Non-National Level

Sunspots were also observed at the non-national level by the people in the vast area outside the capital city of China. Astronomical events were regarded as a part of history by the Chinese for more than two thousand years. There was a long tradition of Chinese historians observing the sky themselves. These individual observations were the sources of astronomical events published in thousands of Fangzhi ( ). Fangzhi is the history of a county (referred to as

). Fangzhi is the history of a county (referred to as  ), or the history of a region that is consisted of several countries (referred to as

), or the history of a region that is consisted of several countries (referred to as  ), or the history of a province (referred to as

), or the history of a province (referred to as  ).

).

Fangzhi was translated as the local gazette (Xu and Jiang, 1982; Yau and Stephenson, 1988), Chinese provincial records (fang-chi) (Eddy, 1983), and the local treatise (Willis et al., 2018).

2.3 Fangzhi and Its Writing Principle

To avoid duplicate records in Fangzhi, most Chinese scholars had abided by a principle that Fangzhi should only record the local events that were either missing, wrong, incomplete or absent in the history books of the whole China ( ).

).

From this principle, Fangzhi generally recorded the sunspots seen by the local people. The HRNSOs recorded in Ming-Shi or other historical books of China were generally not repeated in Fangzhi unless the local people saw sunspots. For example, Lai-Bin-Xian-Zhi (Section 4.15) did not copy any HRNSO in Ming-Shi that circulated widely around China after 1739. Lai-Bin-Xian-Zhi was revised once in 1751, and in that revision, the authors of Lai-Bin-Xian-Zhi did not specify the dates of the HRNSOs in 1618, even though they could know the dates of HRNSOs 10 and 14 clearly from Ming-Shi.

2.4 Observation Locations and Observers

The observation locations and observers in Tables 1 and 2 were determined as listed below:

(case 1) In the books written by court historians, the observer was the National Astronomical Observatory, and the observation location was Beijing.

(case 2) In Fangzhi, the sunspot observer was the writer or some unknown local people, and the observation location was local.

(case 3) In historical books written by civilian historians, when the origin of the record was not given, the observation location was the place of residence of the author, and the author was assumed to be the observer.

3 Compiling HRNSOs

Translations of some Chinese terms and an identification method of duplicate records are discussed here.

3.1 Sunspots Rub the Sun

The two terms  and

and  share the same meaning. However, there is no uniform English translation for the two terms (read Appendix 1. We remark that all the appendices included in this article can be found in the supplementary materials). We think that the record in 832 (

share the same meaning. However, there is no uniform English translation for the two terms (read Appendix 1. We remark that all the appendices included in this article can be found in the supplementary materials). We think that the record in 832 ( , page 160, (Xu, Pankenier, and Jiang, 2000)) is the source of the two terms.

, page 160, (Xu, Pankenier, and Jiang, 2000)) is the source of the two terms.  (rub) is enough to replace

(rub) is enough to replace  or

or  . The translation that the sunspots rubbed the Sun is more simple for the readers. The phenomenon (the sunspots rub the Sun) is due to turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere and visual response of human eyes, not sunspot dynamics.

. The translation that the sunspots rubbed the Sun is more simple for the readers. The phenomenon (the sunspots rub the Sun) is due to turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere and visual response of human eyes, not sunspot dynamics.

3.2 Translation of Hei-Zi or Hei

The English translation of  is a black spot in some catalogues (Wittmann and Xu, 1988; Yau and Stephenson, 1988; Xu, Pankenier, and Jiang, 2000), but the translation was usually associated with a small group. However, as presented in Section 5.8, we discuss that some historians used

is a black spot in some catalogues (Wittmann and Xu, 1988; Yau and Stephenson, 1988; Xu, Pankenier, and Jiang, 2000), but the translation was usually associated with a small group. However, as presented in Section 5.8, we discuss that some historians used  to record large sunspots with various sizes and shapes. In Sections 4.11, 5.6, and 5.7, we find that

to record large sunspots with various sizes and shapes. In Sections 4.11, 5.6, and 5.7, we find that  was sometimes used to record the sunspot presence only. We prefer to translate

was sometimes used to record the sunspot presence only. We prefer to translate  as black objects, read Section 5.8 for details.

as black objects, read Section 5.8 for details.

3.3 Time Terms

Few readers are familiar with the time terms in traditional China. Thus, the terms are given here in the Gregorian calendar, not in Pinyin.

3.4 Duplicate Records

Some HRNSOs have been copied in books written later. It is not easy to identify the duplicate records (DR). The Chinese generally gave no reference in a HRNSO, and the observer was usually not specified. We think that a duplicate HRNSO should meet the following conditions:

i) Condition 1: The duplicate record is identical to the source record, or part of the text in the source record has been deleted from the duplicate record.

ii) Condition 2: The duplicate record was completed later than the source HRNSO.

iii) Condition 3: The source of the duplicate record usually copied other astronomical records in the origin of the source HRNSO, rather than the sunspot record only.

Only when sufficient evidence shows that multiple records were from the same source is this combination reasonable. Anyone who wants to merge multiple HRNSOs should be highly careful, as precious records of sunspot activity would be lost in the combination without sufficient evidence.

4 HRNSOs in 1618

The records were presented here as the scanned images and each HRNSO is highlighted in color in the image. Read Appendix 2 for records typed in classic Chinese.

4.1 HRNSO 1 from Guo-Que on 22 May

This record from  (Guo-Que) as a private history book of the Ming dynasty is shown in Figure 1. Guo-Que was written by the civilian historian Qian Tan (1594 – 1657) from 1621 to 1656. Note here that Guo-Que was a forbidden book in the Qing dynasty, and people were not allowed to read the book.

(Guo-Que) as a private history book of the Ming dynasty is shown in Figure 1. Guo-Que was written by the civilian historian Qian Tan (1594 – 1657) from 1621 to 1656. Note here that Guo-Que was a forbidden book in the Qing dynasty, and people were not allowed to read the book.

HRNSO 1 from  (Guo-Que, page 69, volume 80, a handwritten version), which was completed in 1656 by Qian Tan as a civilian historian. The sunspot record is highlighted in gray. The sunspot was visible on 22 May 1618. The source of this record was not given in the record. It was assumed that the observer was the author, Qian Tan, and the location of sunspot observation was the residence place of Qian Tan, Haining. The sunspots were recorded as

(Guo-Que, page 69, volume 80, a handwritten version), which was completed in 1656 by Qian Tan as a civilian historian. The sunspot record is highlighted in gray. The sunspot was visible on 22 May 1618. The source of this record was not given in the record. It was assumed that the observer was the author, Qian Tan, and the location of sunspot observation was the residence place of Qian Tan, Haining. The sunspots were recorded as  (hei, the black objects).

(hei, the black objects).

The record is given below:

On 22 May, the black objects were fighting in the Sun.

This record in a previous catalogue (Beijing Observatory, 1988) (see page 14) was wrong; the incorrect record in simplified Chinese is given below:

The record above is incorrect due to the conversion of the record from classic Chinese to simplified Chinese. In classic Chinese,  and

and  are two characters with completely different meanings.

are two characters with completely different meanings.  means fight or contest, while

means fight or contest, while  is polysemous.

is polysemous.  has the following explanations: M1) a long-handled container for wine; M2) the name of a measure for volume; M3) the Big Dipper; M4) the Chinese name of a star, Nan-Dou; M5) steep.

has the following explanations: M1) a long-handled container for wine; M2) the name of a measure for volume; M3) the Big Dipper; M4) the Chinese name of a star, Nan-Dou; M5) steep.

The two characters ( and

and  ) with these totally different meanings in classic Chinese were combined into one character (

) with these totally different meanings in classic Chinese were combined into one character ( ) in simplified Chinese. Since the authors of the previous catalogue (Beijing Observatory, 1988) did not notice the difference between

) in simplified Chinese. Since the authors of the previous catalogue (Beijing Observatory, 1988) did not notice the difference between  and

and  in classic Chinese, the record was not correctly converted into simplified Chinese. The English translation of this record in an article (Willis et al., 2005) (see Appendix K in that article) was incorrect inevitably, as the source record in simplified Chinese was wrong. Willis et al. (2005) did not have a discussion to determine the meaning of

in classic Chinese, the record was not correctly converted into simplified Chinese. The English translation of this record in an article (Willis et al., 2005) (see Appendix K in that article) was incorrect inevitably, as the source record in simplified Chinese was wrong. Willis et al. (2005) did not have a discussion to determine the meaning of  from the five explanations mentioned above (M1 – M5).

from the five explanations mentioned above (M1 – M5).

4.2 HRNSO 2 from Shang-He-Xian-Zhi and a Possible Duplicate (DR 1)

HRNSO 2 from  (Shang-He-Xian-Zhi, the 1835 version) is shown in Figure 2a, and the record is given below:

(Shang-He-Xian-Zhi, the 1835 version) is shown in Figure 2a, and the record is given below:

(a) HRNSO 2 from  (Shang-He-Xian-Zhi, page 48, volume 3, the 1835 version). (b) Duplicate Record 1 from

(Shang-He-Xian-Zhi, page 48, volume 3, the 1835 version). (b) Duplicate Record 1 from  (Lin-Yi-Xian-Zhi, page 8, volume 16, the 1837 version) as a possible duplicate of HRNSO 2. (c) HRNSO 3 from

(Lin-Yi-Xian-Zhi, page 8, volume 16, the 1837 version) as a possible duplicate of HRNSO 2. (c) HRNSO 3 from  (Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi, page 75, volume 17, the 1828 version). (d) Duplicate Record 2 from

(Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi, page 75, volume 17, the 1828 version). (d) Duplicate Record 2 from  (Ling-Ling-Xian-Zhi, page 19, volume 12, the 1875 version), as a possible duplicate of HRNSO 3.

(Ling-Ling-Xian-Zhi, page 19, volume 12, the 1875 version), as a possible duplicate of HRNSO 3.

In 1618, from 2 April to 1 May, white vapor traversed the sky in the east direction, and there were black objects in the Sun.

The white vapor is the aurora in white color. The sunspots and the aurora indicate that the Sun was quite active at that time.

We found a sunspot record identical to HRNSO 2 in  (Lin-Yi-Xian-Zhi), as shown in Figure 2b. The record in Lin-Yi-Xian-Zhi was published in 1837, later than HRNSO 2 was published in 1835. Linyi is quite close to Shanghe, approximately at 30.3 km distance. The record (DR 1) in Figure 2b is regarded as a duplicate of HRNSO 2. However, it is still possible that the two records came from the same source of sunspot observations.

(Lin-Yi-Xian-Zhi), as shown in Figure 2b. The record in Lin-Yi-Xian-Zhi was published in 1837, later than HRNSO 2 was published in 1835. Linyi is quite close to Shanghe, approximately at 30.3 km distance. The record (DR 1) in Figure 2b is regarded as a duplicate of HRNSO 2. However, it is still possible that the two records came from the same source of sunspot observations.

4.3 HRNSO 3 from Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi and a Possible Duplicate (DR2)

HRNSO 3 from  (Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi, the 1828 version) is shown in Figure 2c, and the record is given below:

(Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi, the 1828 version) is shown in Figure 2c, and the record is given below:

In summer of 1618, from 2 April to 1 May, there were black objects in the Sun.

Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi is the official history of  (Yongzhou). The authors of Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi (the 1828 version) probably formatted the observation log into the simplest record, as discussed in Section 5.7.

(Yongzhou). The authors of Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi (the 1828 version) probably formatted the observation log into the simplest record, as discussed in Section 5.7.

We found a record identical to HRNSO 3 from  (Ling-Ling-Xian-Zhi, the 1875 version), as shown in Figure 2d. Ling-Ling-Xian-Zhi was published once in 1687. However, HRNSO 3 was not included in the 1687 version. The record in Figure 2d was published in 1875, while HRNSO 3 was published in 1828. Lingling was a separate country belonging to Yongzhou and is now a district of Yongzhou. From Conditions 1 and 3 in Section 3.4, the record (DR 2) in Figure 2d is identified as a duplicate of HRNSO 3. However, it is still possible that the two records were from the same source of sunspot observations.

(Ling-Ling-Xian-Zhi, the 1875 version), as shown in Figure 2d. Ling-Ling-Xian-Zhi was published once in 1687. However, HRNSO 3 was not included in the 1687 version. The record in Figure 2d was published in 1875, while HRNSO 3 was published in 1828. Lingling was a separate country belonging to Yongzhou and is now a district of Yongzhou. From Conditions 1 and 3 in Section 3.4, the record (DR 2) in Figure 2d is identified as a duplicate of HRNSO 3. However, it is still possible that the two records were from the same source of sunspot observations.

4.4 HRNSO 4 from Ming-Hui-Yao

HRNSO 4 from  (Ming-Hui-Yao, the 1875 version) is shown in Figure 3a, and the record is given below:

(Ming-Hui-Yao, the 1875 version) is shown in Figure 3a, and the record is given below:

HRNSOs 4 and 5, and a record necessary to understand HRNSO 4. Each record is highlighted in green. (a) HRNSO 4 from  (Ming-Hui-Yao, page 8, volume 8, the 1875 version in 80 volumes) (b) HRNSO 5 from

(Ming-Hui-Yao, page 8, volume 8, the 1875 version in 80 volumes) (b) HRNSO 5 from  (Chang-Shu-Xian-Si-Zhi, page 79, volume 4, the manuscript version in 1618), the author of HRNSO 5 thought that the sunspots in 1618 were similar to the sunspots in 1554, as shown in panel c. (c) Sunspot record in 1554 from

(Chang-Shu-Xian-Si-Zhi, page 79, volume 4, the manuscript version in 1618), the author of HRNSO 5 thought that the sunspots in 1618 were similar to the sunspots in 1554, as shown in panel c. (c) Sunspot record in 1554 from  (Chang-Shu-Xian-Si-Zhi, page 75, volume 4, the manuscript version in 1618).

(Chang-Shu-Xian-Si-Zhi, page 75, volume 4, the manuscript version in 1618).

In 1618, from 2 April to 1 May, there were black objects in the Sun.

Ming-Hui-Yao was written by Wenbin Long (1824 – 1893) as a private history book of the Ming dynasty. The author claimed to complement the omission of Ming-Shi but not to repeat the recordings in Ming-Shi. In Ming-Hui-Yao, Long usually recorded the sunspots missing in Ming-Shi.

4.5 HRNSO 5 from Chang-Shu-Xian-Si-Zhi

HRNSO 5 from  (Chang-Shu-Xian-Si-Zhi, the manuscript version in 1618) is shown in Figure 3b, and the record is given below:

(Chang-Shu-Xian-Si-Zhi, the manuscript version in 1618) is shown in Figure 3b, and the record is given below:

From 24 May to 21 June, the Sun was covered by the black objects, and the light (sunspots) rubbed the Sun. The case here is similar to that in 1554.

Chang-Shu-Xian-Si-Zhi is a private history book of Changshu ( ). The book was circulated only in the form of manuscripts after its completion.

). The book was circulated only in the form of manuscripts after its completion.

This record is critical to know the number of visible sunspots in June 1618. We found the complete record for the first time, as shown in Figure 3b. The record was incomplete and incorrect in the previous catalogues (Xu and Jiang, 1979; Wittmann and Xu, 1988; Beijing Observatory, 1988; Yau and Stephenson, 1988; Xu and Jiang, 1990; Xu, Pankenier, and Jiang, 2000). The term black light was usually used by the observers in the Ming dynasty to describe large sunspots in a diffuse distribution. We suggest to read records on 30 March 1613 and 12 June 1659 in the Yau catalogue to find out more about the light as the term to record the sunspots.

HRNSO in 1554 is necessary to know the 1618 sunspots in HRNSO 5, as shown in Figure 3c. The 1554 record is given below:

In 1554, from 2 April to 1 May, at sunrise and sunset, there were black objects like the Sun (round in shape) more than a hundred wandering on the limb of the Sun. The Sun was covered by black vapor that rubbed the Sun and looked like a black dish. Sunlight came out around the black vapor, similar to some threads.

The black object like the Sun was a round sunspot group. The black Sun was used by the Chinese to record sunspots in the 17th century; see the records on 29 April 1607 and 3 May 1622 in the Chinese catalogue (Beijing Observatory, 1988).

From the original manuscript in Figure 3b, the Sun was covered by sunspots. Thus, the translation of this record in the Yau catalogue (No. 164 (ii), within the Sun there was again a black sunspot) (Yau and Stephenson, 1988) was wrong.

Since Yao thought that the objects on the Sun in 1618 were similar to those in 1554, Yao did not repeat the record in 1554 for that in 1618 for brevity. Observations from others confirm Yao’s conclusion that the sunspots in 1618 were similar to those in 1554. From Dong’s observation (Section 4.12) and the NAO observation (Section 4.8), the sunspots in June 1618 looked like the black vapor to the two observers. The sunspot distribution in 1618 was exactly the same as that seen by Yao in 1554. Dong had seen a round object (a black Chinese pancake) on the solar disk, and this shape is similar to the sunspot shape (a black disk) seen by Yao in 1554.

Yao saw the sunspots on the solar limb in 1554, and this position is not in the central area of the solar disc, similar to the non-central location (one side of the Sun) in Dong’s observation or NAO observation in 1618 (HRNSOs 8 and 10). Read Section 5.3 for more discussions of the sunspot position. From comparisons of the sunspot distributions, the shapes and positions of the sunspots, Yao’s judgment that the visible sunspots in 1618 were similar to those in 1554 is credible.

4.6 HRNSO 6 from Ming-Shi

This record is from  (Heng-Yun-Shan-Ren-Ming-Shi-Gao, the draft edition of Ming-Shi by Hongxu Wang, published in 1723) as the earliest print version of

(Heng-Yun-Shan-Ren-Ming-Shi-Gao, the draft edition of Ming-Shi by Hongxu Wang, published in 1723) as the earliest print version of  (Ming-Shi), as shown in Figure 4a. Ming-Shi is the official history of the Ming dynasty, written under the organization of the Qing government since 1645. The record is given below:

(Ming-Shi), as shown in Figure 4a. Ming-Shi is the official history of the Ming dynasty, written under the organization of the Qing government since 1645. The record is given below:

(a) HRNSOs 6 (highlighted in green) and 14 (highlighted in purple) from  (Ming-Shi, page 10, volume 124, the first version published by

(Ming-Shi, page 10, volume 124, the first version published by  (Jing-Shen-Tang) in 1723). (b) HRNSO 7 (highlighted in blue) from

(Jing-Shen-Tang) in 1723). (b) HRNSO 7 (highlighted in blue) from  (Chong-Xiang-Ji, page 44, volume 1, the 1623 version) and the first part of HRNSO 12 (highlighted in red) is also in this page. (c) The second part of HRNSO 12 from

(Chong-Xiang-Ji, page 44, volume 1, the 1623 version) and the first part of HRNSO 12 (highlighted in red) is also in this page. (c) The second part of HRNSO 12 from  (Chong-Xiang-Ji, page 44, volume 1, the 1623 version; highlighted in red).

(Chong-Xiang-Ji, page 44, volume 1, the 1623 version; highlighted in red).

From 24 May to 21 June, the black objects were fighting with each other in the Sun.

Since the observer thought that the black spots were fighting, there were probably at least two large sunspot groups. The fighting phenomenon is due to turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere, similar to the rubbing phenomenon (Section 3.1). When significant turbulence occurs in the Earth’s atmosphere, two or more sunspot groups could generate a collision among their separate images, and the observer regarded the collision as fighting objects. Two small sunspots can barely produce the visual effect of fighting for the naked-eye observer.

HRNSO 6 from Ming-Shi was copied by  (Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi, the 1737 version), as shown in Figure 7a. Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi was completed in 1737 after the publication of HRNSO 6. From Conditions 1 and 3 (Section 3.4), the record (DR 3) in Figure 7a is regarded as a duplicate of HRNSO 6. The Yau catalogue used the later record (DR 3) (Yau and Stephenson, 1988) in Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi instead of the earlier record (HRNSO 6) and the translation in the Yau catalogue (“Within the Sun there was black spot like a ladle”) was wrong. Fighting had been misunderstood as a ladle.

(Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi, the 1737 version), as shown in Figure 7a. Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi was completed in 1737 after the publication of HRNSO 6. From Conditions 1 and 3 (Section 3.4), the record (DR 3) in Figure 7a is regarded as a duplicate of HRNSO 6. The Yau catalogue used the later record (DR 3) (Yau and Stephenson, 1988) in Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi instead of the earlier record (HRNSO 6) and the translation in the Yau catalogue (“Within the Sun there was black spot like a ladle”) was wrong. Fighting had been misunderstood as a ladle.

4.7 HRNSO 7 from Chong-Xiang-Ji, 20 and 21 June

HRNSO 7 from  (Chong-Xiang-Ji, the 1623 version) is shown in Figure 4b. The record is given below:

(Chong-Xiang-Ji, the 1623 version) is shown in Figure 4b. The record is given below:

Some unknown persons (or some persons outside Dong’s house) spread the news that black objects were fighting with each other in the Sun on 20-June and 21-June, and the Sun was far from the normal state. Their conversations were loud and noisy.

Chong-Xiang-Ji is the personal anthology of Yingju Dong (1557 – 1639), it was completed in 1623. From the record, the observer was Yingju Dong, and the observation location was Nanjing. This record is important to know the sunspot size in June. However, this record was missing in the English catalogues (Wittmann and Xu, 1988; Yau and Stephenson, 1988; Hayakawa et al., 2017). We discovered the complete record from Chong-Xiang-Ji and present it as an HRNSO for the first time. A record (DR 4) identical to HRNSO 7 was found in Guo-Que. The catalogue (Beijing Observatory, 1988) erroneously took Guo-Que as the source for HRNSO 7.

If only a few people talked about sunspots, the voices would not be described as loud and noisy ( ). From the loud and noisy talks, we think that the oral news of the abnormal Sun was probably widespread by several people in Nanjing. Only the oral news was circulated that Dong, who was far from the ordinary people as a high-rank officer, could hear the word-of-mouth and thought that the people’s voices were loud and noisy.

). From the loud and noisy talks, we think that the oral news of the abnormal Sun was probably widespread by several people in Nanjing. Only the oral news was circulated that Dong, who was far from the ordinary people as a high-rank officer, could hear the word-of-mouth and thought that the people’s voices were loud and noisy.

Note that even ordinary people who did not have the technique of observing sunspots were able to detect and see sunspots, and after observing the Sun, they thought that the Sun was far from its normal state. Only large sunspots can produce such shocking visual effects and cause the sunspot news to be word-of-mouth to a number of ordinary people.

Under normal conditions, the Sun is usually too bright to be observed. June is the rainy season in Nanjing, and the wet atmosphere is helpful for naked-eye observations of the sunspots. We do not think that ordinary people in Nanjing used the jade filters to observe the Sun, as claimed in page 436 of the classic book of Chinese astronomy (Needham and Wang, 1959). The jade filters would be too expensive for ordinary people since the atmosphere is free for everyone.

Since the sunspots were fighting, at least two large sunspot groups were seen by the Nanjing people, as described in Section 4.6.

4.8 HRNSO 8 in Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu

HRNSO 8 from  (Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu, a hand-written version in the Qing dynasty) is shown in Figure 5a. Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu are the royal archives that recorded the activities of the emperor Yixu Zhu (1573 – 1620). The record is given below:

(Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu, a hand-written version in the Qing dynasty) is shown in Figure 5a. Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu are the royal archives that recorded the activities of the emperor Yixu Zhu (1573 – 1620). The record is given below:

(a) HRNSO 8 from  (Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu, page 13, volume 569, a handwritten version in the Qing dynasty). (b) HRNSO 9 from

(Ming-Shen-Zong-Shi-Lu, page 13, volume 569, a handwritten version in the Qing dynasty). (b) HRNSO 9 from  (Guo-Que, page 73, volume 80, a handwritten version). (c) HRNSO 10 from

(Guo-Que, page 73, volume 80, a handwritten version). (c) HRNSO 10 from  (Ming-Shi, page 31, volume 20, the 1723 version published as

(Ming-Shi, page 31, volume 20, the 1723 version published as  ). (d) HRNSO 11 from

). (d) HRNSO 11 from  (Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian, page 6, volume 31, the 1775 version in

(Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian, page 6, volume 31, the 1775 version in  ).

).

From 20 June to 22 June, there was black vapor on one side of the Sun. The black vapor rubbed the Sun, and the black vapor went in and out of the central area of the solar disc for quite a long time. Yingju Dong, who was an officer at the Supreme Court in Nanjing (Nan-Da-Li-Si-Cheng), reported sunspots to the emperor. The Astronomical Bureau and the National Astronomical Observatory in Beijing made no report of the sunspots to the emperor.

Dong was the officer at the Supreme Court in Nanjing, and the term “Astronomical Bureau” given in the Yau catalogue (No. 165) (Yau and Stephenson, 1988) is incorrect. Yau and Stephenson (1988) misunderstood  (Nan-Da-Li-Si) as

(Nan-Da-Li-Si) as  (Nan-Si-Tai).

(Nan-Si-Tai).

4.9 HRNSO 9 in Guo-Que, from 20 June to 22 June

HRNSO 9 from  (Guo-Que, a handwritten version) is shown in Figure 5b, and the record is given below:

(Guo-Que, a handwritten version) is shown in Figure 5b, and the record is given below:

From 20 June, black vapor rubbed the Sun on one side of the Sun for 3 days. The Astronomical Bureau kept the sunspot record from the emperor.

In this record, Qian Tan thought that the officers of the Astronomical Bureau knew the sunspots from the observations of the NAO, as Tan did not write that the Astronomical Bureau did not see the sunspots.

4.10 HRNSO 10 in Ming-Shi, from 20 June to 22 June

HRNSO 10 from  (Ming-Shi, the first version published in 1723) is shown in Figure 5c. The record is given below:

(Ming-Shi, the first version published in 1723) is shown in Figure 5c. The record is given below:

From Bing-Xu to Wu-Zi in leap June, the black vapor rubbed the Sun on one side of the Sun. The black vapor went in and out of the central area of the solar disk.

The date of this record is mistaken. Huang corrected the date error in HRNSO 10 using HRNSO 8 and 11 around 1980 (Huang, 1986).

4.11 HRNSO 11 in Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian, from 20 June to 22 June

HRNSO 11 from  (Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian) is shown in Figure 5d. The lunar month is in Figure 6a. The record is quite special, and it has a separate headline given in a larger font and highlighted in red in Figure 5d.

(Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian) is shown in Figure 5d. The lunar month is in Figure 6a. The record is quite special, and it has a separate headline given in a larger font and highlighted in red in Figure 5d.

The title of the sunspot record is given below:

There were some black objects in the Sun.

The body of the sunspot record is given below:

In this month, from 20 June to 22 June, the black vapor went in and out of the central area of the solar disk. The black vapor rubbed the Sun and it did not dissipate for a long time.

Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian was an official history of the Ming dynasty, and it was completed in 1746, i.e. 128 years later than 1618. The authors of HRNSO 11 were not able to see the sunspots in 1618 and only wrote the record by consulting the earlier records. We think that the historians used HRNSO 8 as the source record or that HRNSO 8 is an approximation of the observation log. Note that the author did not copy the date error in Ming-Shi that has been a widely spread history book since its publication in 1723. The record had been used to correct the date error in Section 4.10.

In our opinion, the historians who did not see the sunspots should copy the original record in their book. However, to our surprise, not only the historians failed to copy the original record, but also they modified the original record. The sunspot position (one side of the Sun) in the source record (HRNSO 8) had been deleted. The lasting time of the visible sunspots were changed to ‘ (not to dissipate for a long time)’ from ‘

(not to dissipate for a long time)’ from ‘ (for a long time)’ in HRNSO 8.

(for a long time)’ in HRNSO 8.

In addition to the two changes, the historians even invented a title ( ) for the record.

) for the record.  was generally used by the Chinese to represent a sunspot group in the 17th century, while

was generally used by the Chinese to represent a sunspot group in the 17th century, while  (black vapor, BV) was generally used by the Chinese to record several sunspot groups that occupied a large portion of the solar disk in the 17th century. See Section 5.1 for details.

(black vapor, BV) was generally used by the Chinese to record several sunspot groups that occupied a large portion of the solar disk in the 17th century. See Section 5.1 for details.

Why did the historians use  in the title of HRNSO 11, but not

in the title of HRNSO 11, but not  reported in other records (HRNSOs 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13)? Did the Chinese observer see only one sunspot (

reported in other records (HRNSOs 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13)? Did the Chinese observer see only one sunspot ( ) as claimed in some previous catalogues or several sunspot groups (

) as claimed in some previous catalogues or several sunspot groups ( , shown in Figure 9a) in a scattered distribution in June 1618?

, shown in Figure 9a) in a scattered distribution in June 1618?

Note here that  in the title was invented by the historians who wrote the record around 1746, and the historians did not see the sunspots in 1618.

in the title was invented by the historians who wrote the record around 1746, and the historians did not see the sunspots in 1618.  was not reported in records earlier than HRNSO 11. All the five earlier records (HRNSOs 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13) only mentioned

was not reported in records earlier than HRNSO 11. All the five earlier records (HRNSOs 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13) only mentioned  (the black vapor, several sunspot groups as a diffusive object), but not

(the black vapor, several sunspot groups as a diffusive object), but not  . Even HRNSO 11 itself confirmed

. Even HRNSO 11 itself confirmed  (the black vapor) in the record typed in small characters (highlighted in purple, Figure 5d).

(the black vapor) in the record typed in small characters (highlighted in purple, Figure 5d).

In summary,  was used here by the court historians as the title of the observation log.

was used here by the court historians as the title of the observation log.

We found a duplicate record (DR 5) of HRNSO 11 from  (Ming-Tong-Jian, the 1873 version), as shown in Figure 6b. The book published in 1873 was written by the civilian historian Xie Xia (1800 – 1875). Xia copied HRNSO 11 published in 1723. However, he did not distinguish between the title and the body of HRNSO 11. After editing of Xia, the record in Figure 6b would be misleading to make some readers think that there was only a black spot in the Sun for three days.

(Ming-Tong-Jian, the 1873 version), as shown in Figure 6b. The book published in 1873 was written by the civilian historian Xie Xia (1800 – 1875). Xia copied HRNSO 11 published in 1723. However, he did not distinguish between the title and the body of HRNSO 11. After editing of Xia, the record in Figure 6b would be misleading to make some readers think that there was only a black spot in the Sun for three days.

4.12 HRNSO 12 in Chong-Xiang-Ji, on 22 June

HRNSO 12 from  (Chong-Xiang-Ji, the 1623 version) is shown in Figure 4b and Figure 4c. The record is given below:

(Chong-Xiang-Ji, the 1623 version) is shown in Figure 4b and Figure 4c. The record is given below:

On 22 June (13:00 – 14:59), I began to observe the Sun by myself. I laid a basin of water towards the Sun at the open ground west of my home. I saw the black vapor wandering on one side of the Sun up and down. Suddenly, the black vapor entered the central area of the solar disk. The sunlight (the sunspots) quivered (the sunspots rubbed the Sun) and was not stable. After a very short time, the sunlight (the black light or the sunspots) became a black Chinese pancake. Part of the Sun was covered by the black Chinese pancake. The black objects reappeared (in the Sun). The sunlight became very weak, and the color of the sunlight was purple. After a very short time, the black vapor appeared again. The (black) light rubbed the Sun, and part of the Sun was covered by the black objects just like before. The process of the weak Sun presented in the previous two paragraphs was repeated three times. Afterwards, color of the sunlight became light yellow. After 17:00, the Sun was dim.

A simplified version (DR 6) of HRNSO 12 was found in Guo-Que. The catalogue (Beijing Observatory, 1988) erroneously took Guo-Que as the source for HRNSO 12, and only a part of HRNSO 12 is available in the catalogue (Beijing Observatory, 1988). The missing part uncovered here is critical to know the sunspots on 22 June and the true meaning of  in HRNSOs 8, 10, and 11. From HRNSO 12, we found that the previous catalogue contained misleading errors in HRNSOs 8 and 10. From this newly discovered record, we found that the Chinese only saw black vapor going in and out of the central area of the solar disk, and they never saw sunspots coming in and out of the Sun, as claimed in some previous catalogues.

in HRNSOs 8, 10, and 11. From HRNSO 12, we found that the previous catalogue contained misleading errors in HRNSOs 8 and 10. From this newly discovered record, we found that the Chinese only saw black vapor going in and out of the central area of the solar disk, and they never saw sunspots coming in and out of the Sun, as claimed in some previous catalogues.

4.13 HRNSO 13 from Song-Jiang-Fu-Zhi, on 22 June

HRNSO 13 from  (Song-Jiang-Fu-Zhi, the 1630 version) is shown in Figure 7a, and the record is given below:

(Song-Jiang-Fu-Zhi, the 1630 version) is shown in Figure 7a, and the record is given below:

(a) HRNSO 13 from  (Song-Jiang-Fu-Zhi, page 27, volume 47, the 1630 version). (b) Duplicate record 6 from

(Song-Jiang-Fu-Zhi, page 27, volume 47, the 1630 version). (b) Duplicate record 6 from  (Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi, page 37, volume 196, the 1737 version), the record is regarded as a duplicate of HRNSO 14. (c) Duplicate record 7 from

(Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi, page 37, volume 196, the 1737 version), the record is regarded as a duplicate of HRNSO 14. (c) Duplicate record 7 from  (Xin-Hui-Xian-Zhi, page 4, volume 14, the 1819 version), the record is identical to HRNSO 14. (d) HRNSO 15 from

(Xin-Hui-Xian-Zhi, page 4, volume 14, the 1819 version), the record is identical to HRNSO 14. (d) HRNSO 15 from  (Lai-Bin-Xian-Zhi, page 142, volume 2, the 1936 version).

(Lai-Bin-Xian-Zhi, page 142, volume 2, the 1936 version).

In 1618, on 22 June, there was black vapor in the Sun.

4.14 HRNSO 14 from Ming-Shi, on 22 June

HRNSO 14 from  (Ming-Shi) is shown in Figure 4a, and the record is given below:

(Ming-Shi) is shown in Figure 4a, and the record is given below:

On 22 June, the black Sun had covered the Sun. The Sun was dim.

(the black Sun) is another term for a sunspot in the Ming dynasty. See the HRNSO on 26 October 1539, 15 May 1624, and 3 May 1622 for more information (Beijing Observatory, 1988). From

(the black Sun) is another term for a sunspot in the Ming dynasty. See the HRNSO on 26 October 1539, 15 May 1624, and 3 May 1622 for more information (Beijing Observatory, 1988). From  used by the observer, we think that the sunspot group was round and large, and the large group looked like another Sun inside the solar disk. The large sunspot group is also confirmed from the verb,

used by the observer, we think that the sunspot group was round and large, and the large group looked like another Sun inside the solar disk. The large sunspot group is also confirmed from the verb,  in the record; see Section 5.2 for details.

in the record; see Section 5.2 for details.

The impressive and large sunspots on 22 June were also confirmed in  (Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi, page 37, volume 196, the 1737 version) and

(Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi, page 37, volume 196, the 1737 version) and  (Xin-Hui-Xian-Zhi, page 4, volume 14, the 1819 version), as shown in Figures 7b and 7c. The two records (Duplicate records 7 and 8) are identified as the duplicate records of HRNSO 14 from Conditions 1 and 2. The duplicate record 6 from Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi did not copy the complete record of HRNSO 14, as

(Xin-Hui-Xian-Zhi, page 4, volume 14, the 1819 version), as shown in Figures 7b and 7c. The two records (Duplicate records 7 and 8) are identified as the duplicate records of HRNSO 14 from Conditions 1 and 2. The duplicate record 6 from Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi did not copy the complete record of HRNSO 14, as  (the black moon or the black disaster) was used instead of

(the black moon or the black disaster) was used instead of  in HRNSO 14. We cannot determine that the observers in Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi saw the black moon or the black disaster. The black moon is similar to the size (large, about 32 arcmin) and shape (round) of the black Sun. The black disaster should be understood as a diffusive object, but not a small sunspot.

in HRNSO 14. We cannot determine that the observers in Fu-Jian-Tong-Zhi saw the black moon or the black disaster. The black moon is similar to the size (large, about 32 arcmin) and shape (round) of the black Sun. The black disaster should be understood as a diffusive object, but not a small sunspot.

4.15 HRNSO 15 from Lai-Bin-Xian-Zhi

HRNSO 15 from  (Lai-Bin-Xian-Zhi, page 142, volume 2, the 1936 version) is shown in Figure 7d, and the record is given below:

(Lai-Bin-Xian-Zhi, page 142, volume 2, the 1936 version) is shown in Figure 7d, and the record is given below:

In 1618 (from 26 January 1618 to 17 November probably), there were some black objects in the Sun.

The sunspot record was before a comet seen on 17 November 1618. Thus, we used 17 November 1618 as the end time of the date range. The first day in  (Wan-Li-46th) is 26 January 1618.

(Wan-Li-46th) is 26 January 1618.

5 Discussions

The sizes, distributions, and positions of the sunspots presented in the last section are discussed here.

5.1 Comparison of Sunspot Distributions in June

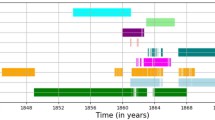

Yao (HRNSO 5), Dong (HRNSO 12), Chen (HRNSO 13), and the NAO staff (HRNSOs 8, 10, and 11) observed sunspots far from each other (four cities) in June 1618, as shown in Figure 8. The records from the four observers are different indicating the records were from the individual experience of each observer rather than the reports of others. Even though the four observers were distant from each other, and each observer saw black vapor (BV) on the Sun. The sunspot distributions from the four observers are exactly the same, described as the BV. The vapor-like sunspots were stable and visible for at least three days (from 20 June to 21 June). The high consistency in the sunspot distribution indicates that the four observations are authentic.

The Chinese in the 17th century usually classified sunspots into two categories: one is  , and the other is

, and the other is  . As shown in Figure 9a,

. As shown in Figure 9a,  represents several groups in a scattered distribution, while

represents several groups in a scattered distribution, while  represents a large group as given in Figure 9b. The sunspot classification of

represents a large group as given in Figure 9b. The sunspot classification of  and

and  was defined by one official astronomy book

was defined by one official astronomy book  (Tian-Yuan-Yu-Li-Xiang-Yi-Fu). The book was completed by the court astronomers and distributed as the official text book of astronomical observations around 1425, and the book had been quite popular among Chinese astronomers since that year.

(Tian-Yuan-Yu-Li-Xiang-Yi-Fu). The book was completed by the court astronomers and distributed as the official text book of astronomical observations around 1425, and the book had been quite popular among Chinese astronomers since that year.

In summary, the Chinese saw vapor-like sunspots that occupied a large portion of the solar disc in June 1618.

5.2 A Diffusive Object with an Impressive Size and a Round Shape in June

A diffusive object with an impressive size and a round shape was reported by Yao, Dong and the National Astronomical Observatory in June. Yao thought that the vapor-like sunspots looked like a black dish (HRNSO 5), while Dong thought that the vapor-like sunspots looked like a black Chinese pancake (HRNSO 12). The black dish and the black Chinese pancake are similar in apparent size and shape, that is, large and round. The large and round sunspots were confirmed by the observation from the National Astronomical Observatory (HRNSO 14). On 22 June, the NAO staff saw a black object on the Sun. The black object was so large and round that the astronomers even thought a black Sun covered the white Sun (peace Sun). The black Sun, the black dish, and the black Chinese pancake share the same round shape. The black dish and the black Chinese pancake are similar in size. The highly consistent shapes and sizes of the visible sunspots indicate that the three records (HRNSOs 5, 12, and 14) are reliable.

If the shape of the black dish reported by Yao is not round, as mentioned above, but oval, the oval shape will not change the conclusion of the highly consistent shapes. We could even find the foreshortening of sunspots near the solar limb, as the shape of the visible sunspots changed from an ellipse (the black dish) to a circle (the black Chinese pancake or the black Sun). Yao discovered the sunspots earlier than Dong and the NAO staff. See Section 5.3 for the discussion.

We have also found other clues about the impressive sizes of the sunspots from the verbs in the HRNSOs. The vapor-like sunspots occupied such a large portion of the Sun that Yao, Dong, and the NAO staff thought that the Sun was covered by the sunspots. Yao used the character  , Dong used the character

, Dong used the character  , and the NAO staff used the character

, and the NAO staff used the character  to describe the sunspots covering the Sun. All the three Chinese characters share a similar meaning in that one object (Sun) was covered by another object (the huge group) indicating the sunspots occupied a considerable area of the whole solar disk. If there was only a small sunspot, the observer would use a most common statement (

to describe the sunspots covering the Sun. All the three Chinese characters share a similar meaning in that one object (Sun) was covered by another object (the huge group) indicating the sunspots occupied a considerable area of the whole solar disk. If there was only a small sunspot, the observer would use a most common statement ( ), but would not use this visually striking description that the black Sun had covered the white Sun. From Figure 9a, one can see how the BV covered the Sun. In the drawing from the Chinese observers, the huge group occupied a considerable portion of the Sun.

), but would not use this visually striking description that the black Sun had covered the white Sun. From Figure 9a, one can see how the BV covered the Sun. In the drawing from the Chinese observers, the huge group occupied a considerable portion of the Sun.

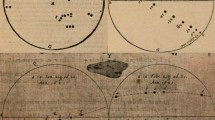

However, the vapor-like, large, and round group reported by Dong, Yao, and the court astronomers was not found in the Malapert drawing (see Figure 10). Malapert believed that the black objects in the Sun resulted from the transit of some astronomical objects, but not of the objects (sunspots) inside the solar photosphere for a long time. Thus, Malapert only drew a small point as the daily observation in June. Comparing Malapert drawings to sunspot drawings of others (like Scheiner in September 1626), we know that Malapert usually did not draw complete groups and that each point is only a marker of the solar satellite or a planet as Malapert believed.

The Malapert drawing in June 1618, taken from the book Avstriaca sidera heliocyclia. Comparing Malapert drawings to sunspot drawings of others (like Scheiner in September 1626), one can find that Malapert usually did not draw the complete group and only drew a sign of the sunspot presence. Each small point is probably only a marker of the astronomical objects transiting the solar disk, as hold by Malapert. It is mistaken to use this figure as the real telescopic observation of black vapor reported by the Chinese. Figure 9a is the Chinese definition of black vapor.

The Chinese have maintained a long tradition of recording sizes of large sunspots with everyday objects (Wang and Li, 2021), including the plum, the egg, etc. By decoding the egg-like sunspots with telescopic observations and radiocarbon dataset, egg-like sunspots were found to correspond to the huge sunspots when solar activity was intense (Wang and Li, 2021). The sunspots in June 1618 were compared with three diffusive objects (a black dish, a black Chinese pancake, and a black Sun). Since the dish or the Chinese pancake is usually larger than the egg to the naked-eye observer, we think that the sunspots in June 1618 were a huge group, and the number of sunspots of the huge group would be around 106 (GSN in the dataset of Hoyt and Schatten (1998) is as indicated in the Introduction. However, the number of egg-like sunspots on 11 February 1911 is 106).

5.3 Comparison of Sunspot Positions in June

Dong (HRNSO 12) and the NAO staff (HRNSO 8, 10, and 11) saw the BV on one side of the Sun on 22 June. The sunspot position was confirmed by Malapert’s drawing. As shown in Figure 10, a small point was found on the east side of the Sun. The reliability of the sunspot reports from Dong and the NAO is validated again by the high consistency of the sunspot positions.

The sunspot position recorded by Yao is the edge of the solar disk, not the side. We think that Yao discovered the occurrence of the huge group much earlier than Dong and the NAO staff. In Figure 10, the sunspot group stayed in the western hemisphere for six days (from 24 June to 29 June). Also, the sunspot probably stayed in the eastern hemisphere for six days (from 18 June to 23 June). Then, sunspots probably appeared on the eastern limb of the solar disk on 18 June. As a civilian historian, Yao needed astronomical events for writing his book, and he has probably observed the sky seriously for decades (read the vivid descriptions of sunspots in 1554 in HRNSO 5). Yao noticed sunspots as soon as they appeared near the eastern limb of the solar disk in June.

5.4 Sunspot Reports from 20 June to 22 June

There were four HRNSOs from 20 June to 22 June. We do not combine the four records (see Appendix 3 for discussions). From the four reports mentioned here, we know that the huge sunspot group with a round shape and an impressive size, seen by Dong on 22 June, HRNSO 12, was already visible on 20 June. The huge group reported by Dong on 22 June maintained its shape and vapor-like distribution for at least three days.

5.5 A Time Range for Avoiding Frequent Reporting

HRNSO 15 was recorded without an exact date. We do not think that the Laibin people forgot the dates of sunspot observations, as they recorded 31 solar eclipses with exact dates on the same page with HNRSO 15 (in Figure 7d). There were probably a number of sunspot reports from the Laibin people in 1618, as confirmed by the other HRNSOs and sunspot drawings on 28 days in 1618. We think that the authors of HRNSO 15 recorded the year only to avoid frequent recording of the sunspots. A HRNSO was generally understood as a fault of an emperor in traditional China. Frequent sunspot recording was usually forbidden in traditional China, as it was an insult to the emperor. The HRNSO recorded with a date range indicates that the sunspots were probably visible frequently in that date range, as presented in HRNSOs 2, 3, 4, and 15. The Chinese used a date range to achieve a delicate balance between documenting sunspots and respecting imperial power, as presented in Section 5.7.

5.6 True Writer of Ri-Zhong-You-Hei-Zi

In Section 4.11, we have found that  was not written by the sunspot observers, but by the historians who never saw the sunspots in 1618. In this section, we would discuss who was the true writer of

was not written by the sunspot observers, but by the historians who never saw the sunspots in 1618. In this section, we would discuss who was the true writer of  in HRNSO 11 again. The clue here is the format of the source book of HRNSO 11. Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian was written with a format referred as

in HRNSO 11 again. The clue here is the format of the source book of HRNSO 11. Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian was written with a format referred as  (Gang-Mu-Ti), and each historical event was written following a format of “a title + event details”. The special format enable the readers to catch the historical events quickly, as historical events are usually mixed together in the chronicles. The title part, typed in large characters, tells the most basic facts about a historical event, while the detailed part, typed in small characters, provides more information about this historical event. The title part was written by the historians as a summary of the historical event.

(Gang-Mu-Ti), and each historical event was written following a format of “a title + event details”. The special format enable the readers to catch the historical events quickly, as historical events are usually mixed together in the chronicles. The title part, typed in large characters, tells the most basic facts about a historical event, while the detailed part, typed in small characters, provides more information about this historical event. The title part was written by the historians as a summary of the historical event.

The format of HRNSO 11 indicates that  was written by the historians. It also confirms our result that

was written by the historians. It also confirms our result that  was not from the sunspot observer, but inserted by the historians as the title, as found in Section 4.11.

was not from the sunspot observer, but inserted by the historians as the title, as found in Section 4.11.

5.7 A Standard Method for Chinese Historians to Record the Sunspots

The six records of  in 1618 (HRNSOs 2, 3, 4, and 11, and DRs 1 and 2) share a special way of recording the date. The special way is to omit the exact day and record the month only, even the historians knew the exact date of the sunspot report. The authors of HRNSO 11 knew the exact date, as the period, from 20 June to 22 June, was specified in the detailed part typed in small characters (Figure 5d). However, only the month was given in the title part of HRNSO 11.

in 1618 (HRNSOs 2, 3, 4, and 11, and DRs 1 and 2) share a special way of recording the date. The special way is to omit the exact day and record the month only, even the historians knew the exact date of the sunspot report. The authors of HRNSO 11 knew the exact date, as the period, from 20 June to 22 June, was specified in the detailed part typed in small characters (Figure 5d). However, only the month was given in the title part of HRNSO 11.

The way of recording the month only in HRNSO 11 is surprisingly consistent with the other five records of  in 1618. Why did the authors of six books (Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian, Ming-Hui-Yao, Shang-He-Xian-Zhi, Lin-Yi-Xian-Zhi, Ling-Ling-Xian-Zhi, and Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi) share the special dating format? We did not think that the exact date was absent in the observation logs, as it is almost impossible for a sunspot observer to omit the day in the observation log, and it is impossible for at least six observers to forget the observation day. Read Section 5.5 for more explanations on the historical background. We think that the special dating format is due to the fact that Chinese historians shared a standard method for formatting the sunspot observation logs in the history books. The standard method for recording the sunspots in the history books is given below.

in 1618. Why did the authors of six books (Zi-Zhi-Tong-Jian-Gang-Mu-San-Bian, Ming-Hui-Yao, Shang-He-Xian-Zhi, Lin-Yi-Xian-Zhi, Ling-Ling-Xian-Zhi, and Yong-Zhou-Fu-Zhi) share the special dating format? We did not think that the exact date was absent in the observation logs, as it is almost impossible for a sunspot observer to omit the day in the observation log, and it is impossible for at least six observers to forget the observation day. Read Section 5.5 for more explanations on the historical background. We think that the special dating format is due to the fact that Chinese historians shared a standard method for formatting the sunspot observation logs in the history books. The standard method for recording the sunspots in the history books is given below.

The original sunspot report or the observation log was deleted by Chinese historians, and only

was recorded in the historical book to standardize the sunspot record.

was recorded in the historical book to standardize the sunspot record.

Chinese historians generally used the standard method to handle various original sunspot reports. Whatever sunspots the observer reported, Chinese historians only recorded  (there were black objects in the Sun). For example, if the detailed part (the observation log or the approximate of the observation log) in Figure 5d was deleted, HRNSO 11 would be only a title of the observation log, just like HRNSOs 2, 3, and 4. Sunspot details in the observation logs in HRNSOs 2, 3, and 4 were deleted by the historians. Then we know why there are so many records of

(there were black objects in the Sun). For example, if the detailed part (the observation log or the approximate of the observation log) in Figure 5d was deleted, HRNSO 11 would be only a title of the observation log, just like HRNSOs 2, 3, and 4. Sunspot details in the observation logs in HRNSOs 2, 3, and 4 were deleted by the historians. Then we know why there are so many records of  in the current collection of HRNSOs.

in the current collection of HRNSOs.

Some simplest HRNSOs ( ) should not be regarded as the observation log, and they did not contain any information about the position or shape of the sunspot. It is sometimes wrong to extract the sunspot number or sunspot shape from the simplest HRNSO including five characters (

) should not be regarded as the observation log, and they did not contain any information about the position or shape of the sunspot. It is sometimes wrong to extract the sunspot number or sunspot shape from the simplest HRNSO including five characters ( ) only.

) only.

5.8 Decoding Hei-Zi as a Symbol for Various Sunspots

The various sizes and shapes of  are confirmed here by telescopic observations and historical records. Four records of

are confirmed here by telescopic observations and historical records. Four records of  were matched with the telescopic observations, as given in Table 3.

were matched with the telescopic observations, as given in Table 3.

. \(n_{sg}\) is the number of sunspot groups (

. \(n_{sg}\) is the number of sunspot groups ( ). Sunspot data of records 1 and 4 are from the work of Wang and Li (2021). Sunspot data of records 2 and 3 are from the Greenwich-heliographic Results (GPR) dataset. The area of the visible sunspots are given in millionths of the solar disk (msd). The last column corresponds to the number of sunspots.

). Sunspot data of records 1 and 4 are from the work of Wang and Li (2021). Sunspot data of records 2 and 3 are from the Greenwich-heliographic Results (GPR) dataset. The area of the visible sunspots are given in millionths of the solar disk (msd). The last column corresponds to the number of sunspots. was regarded as the same object (a spot, usually understood as a small group like a point-like object) in some previous catalogues, with a fixed shape. Carrasco et al. (2020) used the telescopic drawing on 13 September 1856 to validate that

was regarded as the same object (a spot, usually understood as a small group like a point-like object) in some previous catalogues, with a fixed shape. Carrasco et al. (2020) used the telescopic drawing on 13 September 1856 to validate that  was only a small group, and HRNSOs did not imply large sunspots. However, the Chinese did not report that sunspots were seen on 13 September 1856, as only the lunar month was given in the record without an exact date. 23 records in more than 1800 years were used to estimate sunspot sizes of HRNSOs (Wang and Li, 2021), instead of only one record and the study showed that the 23 HRNSOs are observations of huge groups.

was only a small group, and HRNSOs did not imply large sunspots. However, the Chinese did not report that sunspots were seen on 13 September 1856, as only the lunar month was given in the record without an exact date. 23 records in more than 1800 years were used to estimate sunspot sizes of HRNSOs (Wang and Li, 2021), instead of only one record and the study showed that the 23 HRNSOs are observations of huge groups.

The HRNSO on 15 February 1900 (GSN=2) and HRNSO on 30 January 1911 (GSN=0) were used to show that the Chinese observation was not reliable. As presented in the work by Wang and Li (2020), the two reports in the 20th century are not the naked-eye observations following the traditional style. The sunspots in the two records are too small to be seen by a naked-eye observer and are only visible in the telescopic observations as presented by Neuhäuser and Neuhäuser (2016).

All the four HRNSOs in Table 3 were observations of large sunspot groups, and  are diffusive celestial objects with impressive sizes for the observers, not point-like objects or small groups. From Table 3, sizes of the visible sunspots were different and time-varying, never the same. Shapes of

are diffusive celestial objects with impressive sizes for the observers, not point-like objects or small groups. From Table 3, sizes of the visible sunspots were different and time-varying, never the same. Shapes of  are also different, not the same. The shape could be an egg (7 November, 354), or a peach (4 April, 355), or a plum (29 March, 370), or even a fist (4 February, 1905).

are also different, not the same. The shape could be an egg (7 November, 354), or a peach (4 April, 355), or a plum (29 March, 370), or even a fist (4 February, 1905).  should no longer be understood as a fixed object (a small group) with a fixed shape.

should no longer be understood as a fixed object (a small group) with a fixed shape.

From the discussions above, we think that  should not be understood as one static object. It is wrong to determine the number and the shape of the visible sunspots from

should not be understood as one static object. It is wrong to determine the number and the shape of the visible sunspots from  only. To make the translation meet the telescopic observations in Table 3 and the number scale in GSN, we understand

only. To make the translation meet the telescopic observations in Table 3 and the number scale in GSN, we understand  as:

as:

There were black objects in the Sun.

6 Revisited Sunspot Activity in 1618 from HRNSOs

From the HRNSOs rediscovered here and 28 sunspot telescopic drawings in 1618, we established a new scenario of sunspot activity in 1618, as discussed below.

Two sunspots were active in March. Sunspots became even more active from 25 April to 22 May, as Chinese began to report the HRNSOs.

At least two large sunspot groups appeared on 22 May and the two large groups were probably alive until 29 June. The two large groups were visible at the northeastern limb of the Sun approximately on 18 June (27 days after 22 May, just the period of the solar rotation), and the two groups were probably visible until 29 June. The Chinese recorded the two large groups as a diffusive object with a round shape and an impressive size on 22 June. The two large groups looked like a mass of black vapor in a scattered distribution, occupying a considerable area of the solar disk.

The number of sunspot groups from 22 May to 29 June satisfies

From Yao’s observations (see Section 4.5), the groups probably consisted of more than 100 sunspots. Thus, a lower limit for the number of sunspots from 18 June to 22 June (probably expanded to 29 June) is:

In Section 5.2, we also obtained an estimation of the number of sunspots, by comparing the apparent size of sunspots in June (the black dish or the black Chinese pancake) to the egg-like sunspots as:

where 106 is the number of sunspots of the egg-like sunspots on 11 February 1911.

The two estimates of the number of sunspots in June 1618 are obtained by different methods. However, they are close to each other; this means that the two estimates of around 100 are probably close to the true value.

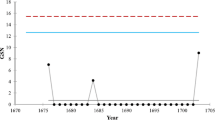

As shown in Figure 11, compared with the sunspot number derived from the annual dataset of radiocarbon, the sunspot series had a false minimum around the year 1618. It is attributed to the fact that the telescopic observations in 1618 are not sufficient to determine the sunspot activity in 1618, and the series from 1618 to 1624 includes artificial noise. There is a peak of the annual frequency of HRNSOs in 1618; this implies that 1618 should not be marked as the solar minimum. The 23 HRNSOs rediscovered provide vital clues to understand the new result that 1620 is the sunspot minimum of the first solar cycle observed using telescopes, instead of 1618.

Annual frequency of HRNSOs and sunspot numbers, from 1600 to 1630. The annual frequency of HRNSOs is computed from the Yau catalogue (Yau and Stephenson, 1988), and the annual frequency in 1618 is 15 from the result found in this article. The yearly GSN is from the NOAA website. The recontructed open-magnetic-field sunspot number (OSN) or smoothed OSN is the sunspot number derived from the open magnetic field in the work by Usoskin et al. (2021).

7 Conclusion

Some sunspot records in 1618 are either missing, wrong or incomplete in the previous catalogues, as presented in Section 4.1, 4.5, and 4.12. Consulting the original record in classic Chinese is a good way to know the real historical sunspot observations. Original records in classic Chinese are essential to avoid various errors in text conversions (from classic Chinese to simplified Chinese (see Section 4.1), from Chinese to English (see Section 4.12)) and manual excerpts (see Section 4.5). Without the 23 records rediscovered here, the real sunspot activity in 1618 could not be known. For example, the sunspots on 22 June 1618 were once said to come in and out of the solar disk in some catalogues. The errors should be corrected to improve the credibility of the catalogues. From the records uncovered in this article, we found that there were at least two large sunspot groups in June 1618 and the Chinese reported the two groups as a diffuse object with an impressive size and a round shape. We also found that some simplest HRNSOs correspond to only the titles of the observation logs, and that some Chinese historians used  to record large sunspots with various sizes and shapes. A number of 23 sunspot reports in only one year is unprecedented in history; this confirms the new result about the solar cycle around 1618. When telescopic drawings are absent, sunspot records in classic Chinese provide valuable observations of sunspots.

to record large sunspots with various sizes and shapes. A number of 23 sunspot reports in only one year is unprecedented in history; this confirms the new result about the solar cycle around 1618. When telescopic drawings are absent, sunspot records in classic Chinese provide valuable observations of sunspots.

References

Beijing Observatory: 1988, Ancient Chinese Astronomical Records, Jiangsu Science and Technology Press, Nanjing.

Brook, T.: 2010, The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties.

Carrasco, V.M.S., Gallego, M.C., Arlt, R., Vaquero, J.M.: 2020, On the use of naked-eye sunspot observations during the Maunder minimum. Astrophys. J. 904(1), 60. DOI. ADS.

Eddy, J.A.: 1983, The Maunder Minimum – a reappraisal. Solar Phys. 89(1), 195. DOI. ADS.

Hayakawa, H., Tamazawa, H., Ebihara, Y., Miyahara, H., Kawamura, A.D., Aoyama, T., Isobe, H.: 2017, Records of sunspots and aurora candidates in the Chinese official histories of the Yuán and Míng dynasties during 1261 – 1644. Publ. Astron. Soc. Japan 69(4), 65. DOI. ADS.

Hoyt, D.V., Schatten, K.H.: 1998, Group sunspot numbers: a new solar activity reconstruction. Solar Phys. 179(1), 189. DOI. ADS.

Huang, Y.: 1986, Ming-Shi-Kao-Zheng, Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing. (In Chinese).

Joseph, N., Wang, L.: 1959, Science and Civilization in China, Vol. III, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Neuhäuser, R., Neuhäuser, D.L.: 2016, Sunspot numbers based on historic records in the 1610s: early telescopic observations by Simon Marius and others. Astron. Nachr. 337(6), 581. DOI. ADS.

Usoskin, I.G., Solanki, S.K., Krivova, N.A., Hofer, B., Kovaltsov, G.A., Wacker, L., Brehm, N., Kromer, B.: 2021, Solar cyclic activity over the last millennium reconstructed from annual 14C data. Astron. Astrophys. 649, A141. DOI. ADS.

Vaquero, J.M., Trigo, R.M.: 2015, Redefining the limit dates for the Maunder Minimum. New Astron. 34, 120. DOI. ADS.

Vaquero, J.M., Gallego, M.C., Usoskin, I.G., Kovaltsov, G.A.: 2011, Revisited sunspot data: a new scenario for the onset of the Maunder Minimum. Astrophys. J. Lett. 731(2), L24. DOI. ADS.

Wang, H., Li, H.: 2019, Do records of sunspot sightings provide reliable indicators of solar maxima for 1613 – 1918? Solar Phys. 294(10), 138. DOI. ADS.

Wang, H., Li, H.: 2020, Are large sunspots dominant in naked-eye sunspot observations for 1819 – 1918? Astrophys. J. 890(2), 134. DOI. ADS.

Wang, H., Li, H.: 2021, Uncovering intense ancient solar activity from naked-eye observations of egg-like sunspots. Astrophys. J. 921(2), 159. DOI. ADS.

Willis, D.M., Armstrong, G.M., Ault, C.E., Stephenson, F.R.: 2005, Identification of possible intense historical geomagnetic storms using combined sunspot and auroral observations from East Asia. Ann. Geophys. 23(3), 945. DOI. ADS.

Willis, D.M., Wilkinson, J., Scott, C.J., Wild, M.N., Stephenson, F.R., Hayakawa, H., Brugge, R., Macdonald, L.T.: 2018, Sunspot observations on 10 and 11 February 1917: a case study in collating known and previously undocumented records. Space Weather 16(11), 1740. DOI. ADS.

Wittmann, A.D., Xu, Z.: 1988, A catalogue of sunspot observations from 165 BC to AD 1684. Vistas Astron. 31(1), 127. DOI. ADS.

Xu, Z., Jiang, Y.: 1979, The solar activity of the 17th century viewed in the light of the sunspot records in the local topographies of China. J. Nanjing Univ. Nat. Sci. 1979(2), 31. ADS.

Xu, Z.-t., Jiang, Y.-t.: 1982, The solar activity in the seventeenth century re-assessed in the light of sunspot records in the local gazettes of China. Chin. Astron. Astrophys. 6(1), 84. DOI. ADS.

Xu, Z., Jiang, Y.: 1990, Research and Modern Applications of the Sunspot Records in Ancient China, Nanjing University Press, Nanjing.

Xu, Z., Pankenier, D.W., Jiang, Y.: 2000, East Asian Archaeoastronomy: Historical Records of Astronomical Observations of China, Japan, and Korea, Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, London.

Yau, K.K.C., Stephenson, F.R.: 1988, A revised catalogue of Far Eastern observations of sunspots (165 BC to AD 1918). Q. J. Roy. Astron. Soc. 29, 175. ADS.

Zolotova, N.V., Ponyavin, D.I.: 2015, The Maunder Minimum is not as grand as it seemed to be. Astrophys. J. 800(1), 42. DOI. ADS.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the sound and essential suggestions from the reviewers in the past two years. We are grateful for the editors’ language editing and comments for the article. Those suggestions, language editing, and comments have improved the manuscript substantially. We are grateful for each organization that offer the historical records to us in the past five years. Special thanks to Hunan Library and National Library of China. All the books or archives in this article were copyright free, as they were completed at least 100 years ago. This work gets financial supports from the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11863001 and 12263001), Research Project of Education-Department in Yunnan Province (No. 2019J0400) and Research Project of Chuxiong Normal University (No. BSQD1801). The group Sunspot Number is provided by NOAA, and the data is downloaded from the website www.ngdc.noaa.gov/stp/space-weather/solar-data/solar-indices/sunspot-numbers/group/ Greenwich-heliographic Results are given by NASA, and it is downloaded from the website (https://solarscience.msfc.nasa.gov/greenwch.shtml).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate that they have no conflicts of interest. The data produced by the authors is given in the article directly.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions