Abstract

This study focuses on housing inequalities across diverse social groups with respect to two housing indicators: subjective housing discrimination; and objective housing deprivation. By scrutinizing the correspondence in inequalities between the two indicators, we enhance the measurement of housing inequality and at the same time we shed light on the relationship between subjective and objective dimensions of housing— a relationship that has received little empirical examination so far. Existing research suggests that housing discrimination can contribute to housing deprivation through two channels: inadequate information and limited economic resources. Our focus is the post-2008 housing market crash era in Ireland. We use two separate large-scale individual-level surveys, the QNHS (2004, 2010, 2014) for analysing housing discrimination and SILC (2014, 2015) for analysing housing deprivation. Our findings reveal a robust convergence between perceptions of housing discrimination and objective housing deprivation across various social groups. Traditionally vulnerable groups—such as young individuals, those with disabilities, non-natives (excluding EU citizenship holders), single parents, and individuals without children—experience both discrimination and deprivation. Notably, certain groups exhibit persistent disparities in discrimination and disadvantage, even after considering factors like human capital, regional and tenure differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Housing extends its relevance far beyond mere security and shelter, playing a pivotal role in shaping overall health and well-being (Clapham et al., 2017). Not only the ownership of the house (Miao & Wu, 2023) but also the quality of the dwelling (Howden-Chapman et al., 2023), as well as experiences connected to housing such as eviction (Hoke & Beon, 2021), exert a substantial impact. As it perpetuates inequalities by influencing health, wealth, educational, and occupational outcomes, the examination of housing is of extreme relevance, and the measurement of housing outcomes is a challenging field of study.

This study explores subjective housing discrimination and objective housing deprivation and the convergence of these two dimensions across distinct social groups. Housing discrimination pertains to an individual’s perception of facing discrimination while seeking housing, while housing deprivation encompasses inadequacies in a range of items related to housing quality. By jointly focusing on these two dimensions of the housing phenomenon, we aim to jointly fill two main gaps. First, from a methodological standpoint, our approach enables us to enhance the validity of our measurement of the degree of housing inequality. While we do not have linked subjective and objective indicators for the same individuals, we triangulate subjective self-reported discrimination with objective deprivation measures for specific/defined social groups over the same time period in the same context. In fact, the triangulation of subjective and objective indicators is common practice in social research (for recent examples see Heylen, 2023 and Oh et al., 2022). On the other hand, looking at the occurrence of housing discrimination and deprivation across distinct social groups also allows us to identify those groups who deserve particular attention and policy intervention. Second, from a substantive standpoint, while theoretical considerations linking discrimination and quality have been often made in the housing literature (Galster, 1992), there is a lack of empirical evidence. In particular, it has been posited that socioeconomic resources, geographical position, and housing tenure are common causes of these two conditions, and we seek to estimate the prevalence of discrimination and deprivation, as well as their correspondence, after accounting for these factors.

We set our study in Ireland and draw on individual-level data from multiple waves of two representative datasets. Ireland is a particularly convenient case study because of the dramatic and rapid changes that the housing market has witnessed over the last decade with high volatility in private and social housing supply as well as on sales and rental prices. Moreover, in recent years, the investigation of housing discrimination and its consequences has gained greater urgency due to the significant shortage of housing and affordability challenges experienced in this country, as well as in many other countries all over the globe.

This article aims at contributing to existing research in three ways. First, it provides new evidence of perceived discrimination coming from survey data; and second, it focuses on a wide number of minority groups. These are important additions to existing research on housing discrimination which is very much populated by field experiments focusing on discrimination enacted by selected groups against specific minority groups (especially focusing on ethnic and gender dimension). Survey data, differently from experiments, allows the identification of the prevalence of housing discrimination in society. Third, most importantly, this article contributes to existing research by providing evidence on the extent to which the same social groups experience both discrimination and deprivation in housing, which implies a situation of double disadvantage.

2 Housing Discrimination, Housing Deprivation, and the Link Between the Two

2.1 Housing Discrimination

Discrimination, defined as unequal treatment based on ethnicity, age, sex, or disability, has a profound impact on the housing sector (Pager & Shepherd, 2008; Small and Pager, 2020). This is especially evident in the allocation of rented and sold properties (Auspurg et al., 2019; Flage, 2018; Rosen et al., 2021).

Two primary mechanisms of discrimination, initially identified in labour market research, are taste-based and statistical discrimination. Taste-based discrimination (Becker, 1957) occurs when sellers, landlords, and real estate agents favour members of their own group and assign a price to this preference. If these preferences are widespread, minorities may have to pay more for housing or be relegated to lower-quality accommodation. Statistical discrimination (Arrow, 1972) happens when sellers, landlords, and agents, seeking “high-quality” tenants or buyers, rely on stereotypes due to imperfect information about clients. Ghekiere et al. (2022) expanded these concepts to housing, distinguishing between agent taste-based, owner taste-based, and neighborhood taste-based discrimination. This framework suggests that all parties involved in housing allocation might discriminate against renters or buyers based on explicit or perceived prejudices, resulting in lower quality and segregated housing for these groups.

A substantial body of empirical literature has aimed to detect and understand these discrimination mechanisms through field experiments, such as fictitious applications, audits, phone calls, and especially correspondence tests. Flage (2018) summarized extensive evidence of discrimination in the housing market in the US (e.g., Ewens et al., 2014; Hanson & Hawley, 2011; Hanson & Santas, 2014) and Europe (e.g., Auspurg et al., 2017; Baldini & Federici, 2011; Bosch et al., 2010). Most studies have focused on ethnic discrimination against non-native applicants and gender discrimination against male applicants, while disability and age discrimination are less explored (e.g., Fumarco, 2017). A meta-analysis by Auspurg et al. (2019) showed that although ethnic discrimination in rental housing has decreased over time, it remains significant in most Western countries. At the same time, reviewing research on discrimination against short-time renters in sharing economic platforms, Abramova (2024) showed that the traditional forms of discrimination are still in place in the gig economy. Recent field experiments are exploring the intersectional nature of discrimination, highlighting multiple layers of discrimination (e.g., Ghekiere et al., 2022).

There are few direct studies of discrimination in the housing market in Ireland. Using a field experiment, Gusciute et al. (2020) found evidence of ethnic discrimination in the private rental housing market in Ireland: 40% of Irish applicants were invited to a viewing, 35% of Polish applicants, and just 25% of Nigerian applicants. The study also found gender discrimination against men and an intersectional effect whereby ethnic minority men were the least likely to receive invitations to view.

Despite being the gold standard in discrimination research, field experiments have limitations (Aliu, 2024; Auspurg et al., 2019; Ross & Turner, 2005). They often lack generalisability to the overall population as they measure discrimination enacted only in specific settings, such as online platforms or by specific groups (e.g. letting agents). Additionally, field experiments tend to focus on the initial step of housing allocation, such as screening or invitations for viewings, missing discrimination present in other dynamics of housing, and tend to focus on only one or two protected grounds (mostly ethnicity and gender). For Ireland, documentary analysis of legal cases complemented with qualitative interviews (Hearne & Walsh, 2021) indeed revealed ethnic minorities, single parents, and individuals with disabilities facing multiple forms of discrimination in both seeking and maintaining tenancies based on receipt of housing assistance.

A method that can potentially complement evidence from field experiments in investigating the prevalence of housing discrimination involves using representative survey data to study self-reported experiences. Although highly educated individuals tend to report discrimination more frequently (Bond et al., 2010), perceived discrimination is crucial as it correlates with health, life satisfaction, and social integration outcomes (Cross et al., 2023; Safi, 2010; Yang et al., 2016). Most research on perceived discrimination focuses on the labour market (e.g., Rafferty, 2020), with few studies examining the housing market (Aliu, 2024; Dion, 2001). There is evidence linking perceived discrimination to residential segregation (Dill & Jirjahn, 2014), emphasising the relationship between discrimination and limited housing choices. Additionally, studies on price discrimination in the US housing market have found that ethnic minorities often pay a premium for properties, all else being equal (Bayer et al., 2017; Ihlanfeldt & Mayock, 2009). Overall, while experimental research on housing discrimination is evolving, particularly in the areas of ethnicity and gender, the use of self-reported measures to understand discrimination prevalence across various social groups is much more underdeveloped.

2.2 Housing Deprivation

Housing deprivation is conceived as the experience of accommodation problems: bad conditions of the dwelling, inadequate equipment and facilities, unaffordable costs of utilities, and poor-quality neighbourhoodsFootnote 1 (Nolan & Winston, 2011). As an enforced lack of items, housing deprivation is a dimension of material deprivation (Whelan & Maître, 2012). This measure is also related to the concept of adequate housing in the human rights literature which includes the (physical) quality of housing alongside accessibility, affordability, security of tenure, cultural adequacy, quality, and location (neighbourhood quality and access to services).

Housing quality conditions have been investigated with regard to both between-countries and within-countries variations. As for cross-country differences, we limit ourselves to the position of our case study in comparison with other European countries. As for within-countries variations, we consider inequalities in housing deprivation across different social groups.

As of 2014 (Kennedy & Winston, 2019), Ireland was with the other EU15 countries among the ones with the best housing quality, having an intermediate position within this cluster, and performing particularly well in terms of overcrowding. Showing a share of households reporting bad quality of dwellings around 20%, values are in line with countries such as Germany and Denmark. In a more recent study by Clair et al. (2019) leveraging on a composite measure of housing precariousness also including deprivation, Ireland is instead found to lie in the middle of the distribution of precariousness. Borg (2015) investigated to what extent the characteristics of the rental sector can account for between-country differences in housing deprivation, distinguishing countries with an integrated rental system (characterized by small differences between the profit and non-profit rental sectors) and with a dual rental system (characterized instead by significant differences between the profit and non-profit rental sectors). She found a negative macro association between the share of the integrated rental sector and housing deprivation, which can be explained mostly by the lower likelihood of homeownership among low-income households and the competition between public and private sector in providing decent quality. In her analysis, Ireland proved to be a country with a relatively low level of integrated rental sector but also relatively low levels of housing deprivation. A more comprehensive institutional explanation of the Irish case was advanced by Norris and Domański (2009), who showed that Ireland is unique as all the three main societal institutions (state, market, and family) are relevant players in the housing provision, and this concurs in lowering the intensity of poor housing outcomes.

Moving instead to within country variations in housing deprivation, past research on material deprivation has explored the extent to which social groups defined by sociodemographic characteristics experience housing deprivation. In the European context, previous research has identified structurally vulnerable groups – defined in terms of gender, age, disability, ethnicity, and household structure – to be particularly exposed to housing deprivation because of their limited access to necessary economic resources. This is especially true in those countries, such as Ireland, where market institutions play a greater role in household welfare (Whelan & Maître, 2012). However, the ability to obtain economic resources is partly mediated by characteristics such as education, employment and occupation which are positively associated with income – and which are unevenly distributed across these groups. To make two examples: looking at age, working-age population may be in a better position to have sufficient resources to maintain or improve their dwellings’ quality than retired population; similarly, looking at household structure, individuals who are in two earners households are obviously better shielded against housing deprivation. However, it is worth noting that mechanisms other than access to economic resources may underlie housing deprivation – including discrimination. Lastly, different housing tenures might entail different overall characteristics of the dwellings, and thus influence housing deprivation. In this regard, Watson and Corrigan (2019) found for most indicators that renters have two times the odds of experiencing bad quality housing than homeowners, but private renters enjoy better housing quality than renters through social housing.

2.3 Linking Discrimination and Deprivation in Housing

According to Galster (1992), housing discrimination could be a driver of housing deprivation via one direct and one indirect effect. First, individuals who were discriminated against in the housing search process have limited information about desirable characteristics of the neighbourhood and dwelling. Second, discrimination is tightly connected with economic disparities and consequently individuals who were discriminated against might lack the economic resources to obtain decent living conditions in their dwellings.

Indeed, as also outlined when reviewing housing discrimination literature, existing research indicates that discrimination in housing brings long-lasting consequences on housing preferences and disparities in the quality of residential conditions (Osypuk & Acevedo-Garcia, 2010; Greenberg et al., 2016; Rothstein, 2017; Rosenblatt & Cossyleon, 2018). To exemplify this reasoning, in two recent contributions to the US case, Christensen and Timmins (2022, 2023) found that minority buyers are steered toward residential areas and this exposes them to worse economic, health, and social conditions, and that constraints in housing search due to discrimination cost around 3–4% of income.

Assessing the causal link between discrimination and deprivation and evaluating the role of direct and indirect mechanisms is beyond the aims of the present paper. Instead, we are interested in describing the occurrence of these two negative conditions across social groups, which represents a condition of double disadvantage in the case the same groups experience both conditions. The association between these two dimensions across different sociodemographic groups has not been empirically analysed and we aim to do so in the Irish context, which represents a compelling case study.

3 The Irish Context

For the majority of the 20th century, owner occupancy prevailed as the primary form of tenure in the Irish housing sector. Simultaneously, there existed a substantial social housing system, notable for its early implementation of tenant purchase scheme. This contributed further to high levels of homeownership. In recent decades, however, social housing has dwindled as a percentage of the overall housing stock, resulting in markedly increased pressures on the private rented market. According to Census data, the proportion of households in the private rented sector increased from approximately 10 per cent in 2006 to 19 per cent in 2016, and has remained roughly at the same level today (CSO, 2007, 2023).

The construction of residential property came to a standstill after the onset of the Great Recession of 2008 where the annual average of units being built fell from almost 85,000 units over the period 2005–2007 to a low 8,000 units by 2013 (Egan & McQuinn, 2022). Rents and sales prices collapsed in this period, but so too did household income, resulting in a significant increase of people struggling to meet housings costs (Corrigan et al., 2019). Over the course of the recovery, the rapidly growing population combined with over a decade of under-investment has resulted in rapid rental and sales price inflation and a homelessness crisis. Nationwide rental price data compiled by the Residential Tenancies Board shows that the standardised average rent increased by 45% from the first quarter of 2011 to the second quarter of 2018 (O’Toole et al., 2019). At the same time, residential property prices increased of about 35% over the same period and the most recent figure shows an increase of roughly 75% between 2011 and March 2023 (CSO 2023). Even greater proportional increases (approximately 80 per cent) were recorded in Census data on the homeless population between 2011 and 2016.

It is worth noting that the minority groups we consider in this paper are not distributed across tenure statuses in the same way as the majority population. In fact, many are heavily concentrated in the private rented sector. This is particularly true for non-Irish nationals, whose recent arrival in Ireland makes them unlikely to be homeowners (Barret et al., 2017), and ineligible for social housing.

4 Data & Measures

4.1 Housing Discrimination

The analysis of housing discrimination in this study relies on data from the Quarterly National Household Survey (QNHS). The QNHS is a highly reliable and nationally representative household survey, gathering extensive information from a sizable sample of individuals aged 15 and above, ranging from approximately 15,000 to nearly 25,000 respondents across various years. To ensure more robust estimates, the data from waves 2004, 2010, and 2014 were pooled together, resulting in a total sample of over 56,000 individuals. We control for year in the models, to take account of period effects given that attitudes towards out-groups and discrimination are likely to be influenced by the changing economic context and housing market (McGinnity & Kingston, 2017; McGinnity et al., 2017).

Crucially, the survey incorporates the ‘Equality module’, which specifically collects data on the experiences of discrimination in different domains, including in access to housing. Participants aged 18 and over were asked, ‘In the past two years, have you personally felt discriminated against while you were looking for housing or accommodation?’ The potential responses were: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Not applicable’ (if not involved in searching for housing/accommodation during the previous two years), and ‘Don’t know’ (excluded from the analysis as they were involved in the search but uncertain about discrimination).

By considering only individuals who were actively seeking accommodation during the study period, the final analytical sample consisted of 14,829 participants. The study’s outcome variable categorized respondents as either ‘Not having felt discriminated against’ (coded as 0) or ‘Having felt discriminated against’ (coded as 1). This dichotomous outcome was then modelled using logistic regression.

While the survey is of high quality, one potential source of bias concerns the period in which information refers to. The experience of discrimination refers to the two years preceding the survey. Differently, other information pertains to the time of the survey interview. While this is not a problem for most characteristics considered, it could be an issue for that information that tend to vary over time, including housing tenure and employment status.

For example, housing tenure reflects the housing arrangement at the time of the interview, as said. This means that individuals who experienced discrimination while looking for accommodation might have ended up in a different housing arrangement than what they were seeking. For instance, someone who faced discrimination while trying to buy a house might have chosen to rent instead. Additionally, ‘indirect’ housing discrimination might occur when individuals attempting to buy a house encounter difficulties in securing a mortgage, leading to discrimination in financial services (which is reported separately in the ‘Equality module’). The consequences of such discrimination would also affect housing access. Consequently, discrimination in access to owner-occupied housing could be underreported in the survey data.

4.2 Housing Deprivation

The analysis of housing deprivation, on the other hand, is based on data from the 2014 and 2015 Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC). The SILC is an annual household survey conducted by CSO since 2003 and serves as the official data source for estimating income, living conditions, poverty, and social exclusion (CSO, 2017b).

We pooled together the SILC data for 2014 and 2015 which resulted into a total sample of 10,938 households and 27,871 individuals. Pooling was necessary given that the number of some of the groups of interest, such as migrants by nationality, was too small in only one wave. To ensure representation of the total Irish population, we use household and individual weights (see Lafferty & McCormack, 2015, p. 13–14). Consistent with the approach used for analysing housing discrimination, the unit of analysis for housing deprivation is individuals aged 18 and over.

Housing deprivation specifically focuses on the structural conditions and amenities available within the house. We employed factor analysis to assess the measures of housing conditions present in the SILC data. This analysis revealed that four items are closely related and loaded onto one factor, which we refer to as “housing deprivation”. These items are as follows:

-

Leaking roof, damp walls/floors/foundation, or rot in window frame or floor;

-

Problems with the dwelling: too dark, not enough light;

-

Deprived of central heating;

-

Deprived of double glazing.Footnote 2

In this study we considered a household to experience housing deprivation if at least one of the four items have been selected. We also identified a second, very basic, dimension of housing deprivation consisting of lack of bath/shower and toilet facilities. However, we decided not to consider this form of deprivation as it is extremely rare and would not allow analysis across subgroups.

4.3 Social Groups Definition

As said, we consider discrimination and inequality in housing for a number of social groups defined by gender, age, disability, nationality, and family status. The groups are defined as follows.

Gender distinguishes between male and female. Age is grouped in classes as follows: 18–34; 35–44; 45–54; 55–64; and 65+. Individuals are considered to have a disability if they have been limited or strongly limited in their daily activities because of health issues for at least the last six months.

Concerning nationality, we distinguishing between Irish; the United Kingdom; old EU, namely the Member States which acceded before 2004 excluding Ireland and the UK (these include Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden); new EU, namely the Member States that acceded between 2004 and 2007 (these include Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia); and non-EU countries.

Regarding household composition, individuals have been classified into four distinct categories according to their household characteristics. Precisely, these categories encompass single-person households composed of adults who live alone; lone parent households, comprising one individual aged 18 or above who is the sole parents of children (below 18) in the household; households comprising two or more adults but no children below 18 years old; and households with two or more adults and children under 18.

4.4 Correlates of Social Group Membership, Discrimination and Deprivation

As said, membership to social groups such as young people, people with disabilities, non-natives (non-EU citizens), lone parents and childless singles in Ireland is linked to other relevant characteristics which are likely related to discrimination and deprivation. These characteristics include individual and family aspects such as human capital and socio-economic status, as well as contextual aspects and the housing market such as the area of residence and housing tenure. Therefore, we study whether social groups experience housing discrimination and deprivation net of compositional factors. As a general rule, we did our best to harmonize measures across the two datasets used.

We measure human capital through the level of education and distinguish between lower secondary or lower education; higher/post-secondary education; and tertiary education. Roughly 1% of the observations did not have valid information on education, therefore we included these observations in the analyses in a residual missing category. Socio-economic status is captured by employment status, which distinguishes between employed; unemployed; inactive; and student. Students are identified as a separate group in the analysis because they tend to occupy a distinctive section of housing market and there is previous evidence that they are exposed to poorer quality housing (HEA 20152019). [Moreover, only for the housing deprivation analyses, we consider household income coded in quintiles. Unfortunately, the QNHS data we use for housing discrimination does not include this information.

Contextual differences and the housing market are captured via: the degree of urbanization of the area of residence that distinguishes between rural versus urban areas; the region of residence coded as South/East of Ireland; Border, Midlands, West of Ireland; and Dublin; housing tenure distinguishes between homeowners (with or without a mortgage); Local Authority renters; and renters in the private sector.Footnote 3

5 Results

5.1 Inequality in Tenure Across Social Groups

First, we investigate the heterogeneity in housing tenures across social groups as of 2014/2015, using the SILC samples. As mentioned above, housing tenure represents as an important contextual element that has been shown to be associated with the quality of housing (Watson & Corrigan, 2019). Specifically, homeownership is associated with the better housing conditions while renting through social housing is associated with the worst conditions, with private renting falling somewhere in the middle.

Table 1 shows that, overall, roughly two third of the population live in owner-occupied housing, just under 10 per cent of the population is located in social housing while the remaining 17% are private renters. However, there is great variation across social groups. Homeownership is somehow evenly represented across social groups, the most significant exceptions being migrants from new EU Member States (9.1%) and non-EU countries (20.2%) as well as lone parents (30.7%). Certain groups are particularly over-represented in the private rented sector, these include particularly young people aged 18–34 (33%), lone parents (35.8%) and migrants, except those from the UK. Also in this case, the figures for migrants from new EU Member States and non-EU countries are striking with 85.8% and 75.8%, respectively, renting in the private sector. Migrants and young people represent ‘new’ entrants to the housing market and are particularly affected by entry barriers to the mortgage market. Eligibility rules for social housing also tend to disadvantage non-Irish nationals such that they have to rely on the private rental sector. The eligibility criteria on access to social housing support for non-Irish nationals is described in Circular Housing 41/2012 (DECLG, 2012). It shows that while there is no difference in eligibility criteria between Irish nationals and UK nationals, there are some restrictions tight to employment status for EEA nationals, and to the length of residence (with a minimum of five years) and having a current valid stamp for non-EEA nationals.Footnote 4

Finally, concerning local authority renting, people with a disability (15.3%) and especially lone parents (33.5%) are significantly over-represented in such housing arrangement, a pattern likely to be influenced by the high levels of income poverty among these two groups (Watson & Corrigan, 2019) and the priority banding set by local authorities.

To sum up, with the only exception being gender, for all the social groups under scrutiny we found differences in distribution of housing tenure. Overall, young people, people with a disability, migrants from new EU Member States and non-EU countries as well as lone parents emerge to be located in the housing arrangements associated with the less advantaged housing conditions.

Given the stark differences across groups in housing tenure, in subsequent multivariate analyses we investigate whether groups differences in housing discrimination and deprivation can be explained by variation in housing tenure.

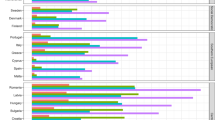

5.2 Housing Discrimination

We turn now to the core of this paper and analyse the experience of discrimination in looking for housing or accommodation across groups. Overall, housing discrimination was reported by about 4% of those seeking accommodation, although with large differences across groups. Table 2 reports logistic regression models where coefficients are expressed in odds ratios, for the risk of experiencing discrimination in looking for housing or accommodation. The models presented include the relevant variables step by step. In the first model we only include the social groups of our interest – this implies that the coefficients associated to one characteristic are already net of compositional effects due to the other characteristics; in the second model we control for level of education and employment status of individuals; the third model controls for the region where people live and survey year; finally, the last model includes housing tenure. Proceeding in this way allows us to explore how compositional factors in terms of human capital and socio-economic status, the context and housing tenure account for the experience of discrimination of certain groups.

Starting with gender, we observe an odds ratio of about 1, meaning that females do not experience a substantively different risk of discrimination compared to male. This holds across all the four models, i.e. irrespective of possible compositional differences characterising the groups of men and women.

Moving to age, Model 1 shows a clear gradient for which the younger the individual the higher the likelihood of reporting housing discrimination. For example, the youngest group is about 6 times more likely to be discriminated compared to the over 65 group (the reference group). Individuals aged 35–44 and 45–54 are also strongly discriminated, reporting odds ratios of 4.6 and 4.3 respectively. When we consider compositional factors in terms of socioeconomic background (Model 2), age inequality strengthens. Specifically, the youngest group becomes 11.5 times more likely to be discriminated compared to the oldest group (Model 2). This is because younger people tend to have a higher level of education and not to be economically inactive/retired. Because these characteristics are associated with lower discrimination, if we do not take into account compositional differences between younger and older individuals, we would underestimate age inequality. Similar results emerge once we control for the region where people live (Model 3). Because younger people live in contexts subjected to less discrimination, once we consider this characteristic discrimination increases for them. Compared to individuals older than 65, younger groups have between 9 (45–54) and 14 (18–34) times higher likelihood of experiencing discrimination. Finally, housing tenure, emerges to be very important in accounting for age inequality as it decreases the age gradient for all age groups (Model 4). The reduction in the effects can be explained by the fact that older people are overrepresented among the less discriminated group of homeowners (92 per cent of the over 65 group are homeowners) compared to young people who are more likely to be private renters (54 per cent of under 34 years old) (see Table 1).

People with disability report higher discrimination levels that people without disability – odds ratio of 2.8 in Model 1. This disadvantage is only partly offset by compositional factors, most importantly by human capital and socioeconomic status. In fact, people with disability have lower levels of education and are more likely to be inactive which make them more exposed to discrimination. Once we account for all compositional characteristics, people with disability are almost twice (1.8) as likely to experience discrimination than people without disability (Model 2–4).

A further line of social stratification is represented by the migration status of individuals, here captured by the nationality of individuals. Groups for which we observe higher risks of discrimination as compared to the Irish nationals are people from Old EU Member States (odds ratio of 2) and especially people from non-EU countries (odds ratio of 2.5). However, once we take into account compositional differences, group differences decrease and turn to be statistically non-significant. Housing tenure plays a particularly relevant role in accounting for group differences.

Finally, family status emerges to be relevant for housing discrimination. Individuals in families with two or more adults and no children (the reference group) appear to be the less discriminated. On the contrary, lone parents are the most at risk: 5 times as likely as the reference group to report housing discrimination (Model 1). Individuals in one-person families and in families with two or more adults and children fall in the middle – however, differences in discrimination for these groups is explained by compositional factors (Model 2–4). Conversely, even after controlling for compositional factors lone parents remain roughly 3 times more at risk of discrimination as compared to the reference group (Model 4).

Results presented above have shown that certain groups are far more at risk of discrimination than others. Specifically, the groups who are particularly disadvantaged when looking for housing are individuals under 54 who are significantly more likely to report discrimination as compared to older adults; individuals with a disability compared to individuals without a disability; and lone parents.

In the next section we investigate whether the same groups which are disadvantaged with respect to discrimination in looking for housing or accommodation are also disadvantaged in terms of housing quality as measured by housing deprivation.

5.3 Housing Deprivation

Overall, 25% of the population experience housing deprivation – with marked differences across groups. We employ the exact same modelling strategy than for the housing discrimination analysis. Table 3 reports four stepwise logistic regression models where a derived, objective measure of housing deprivation is expressed in odds ratios: in the first model we include the relevant social groups, thus accounting only for between groups compositional differences; in the second model we add level of education, employment status, and household income; in the third model, we add the degree of urbanization, region of residence, and survey year; lastly, in the fourth model we add housing tenure. Just like for housing discrimination, with this analysis we explore how compositional factors in terms of human capital and socio-economic status, the context and housing tenure account for the experience of deprivation of social groups denoted by gender, age, disability, nationality, and family status. Variables and categories are identical to the housing discrimination models, the two only differences being the inclusion in the models of household income and degree of urbanization of the area of residence of the respondents.

Looking at gender, we do not detect differences in the likelihood of experiencing housing deprivation, and this result is consistent across all model specifications.

A gradient in housing deprivation is instead observed when looking at age, with younger people more deprived than older people. Compared to the over 65 group, the 18–34 group is about 1.5 times more likely to be housing deprived and this difference holds across model specifications. Instead, groups in between (35–44, 45–54, and 55–64) have an odds ratio that is closer to 1 in the baseline model, which slightly strengthens when controlling for socio-economic characteristics (Model 2) and contextual characteristics (Model 3) that are positively correlated with housing deprivation. Finally, most age group differences loose magnitude and statistical significance when adding housing tenure differences (Model 4), as a result of the housing tenure gradient, for which younger people are more likely to be in the disadvantaged housing tenures (see Table 1).

People with a disability are more at risk of being deprived in their housing conditions – odds ratio of about 1.8 in model 1. This disadvantage is not offset when adding all the correlates in the subsequent models.

We observe different patterns of risks of housing deprivation associated with the nationality of the individuals, considering Irish citizens as the reference category. First, UK nationals living in Ireland are not observed to be at higher risk of housing deprivation than Irish nationals, and this holds true across all model’s specifications. Second, Old EU nationals are slightly more at risk of housing deprivation than Irish nationals, and the difference is detectable (odds ratio 1.6 in model 3) if we account for compositional differences in the area of living. Thirdly and interestingly, New EU nationals are less likely than Irish nationals (odds ratio 0.7 in model 2 and 3, odds ratio 0.5 in model 4) to experience housing deprivation if we control for correlates of housing deprivation. This finding is interesting if we consider that most of this groups is not composed by homeowners (see Table 1) and thus is likely to be due to differences in the dwelling conditions of this group compared to the Irish nationals. Fourth, Non-EU nationals have a greater risk of housing deprivation (odds ratio 1.6 in model 1). However, this difference decreases and becomes statistically not significant when considering compositional differences in socio-economic conditions (Model 2), and disappears when considering housing tenure (Model 4).

Lastly, moving to differences associated with family status, we observe that individuals in families with two or more adults without children (the reference group) as well as those with children are the least disadvantaged in housing quality conditions. Lone parents are at higher risk of housing deprivation than families with two adults (odds ratio 1.7 in model 1), but this difference is found to be driven by compositional differences in correlates. On the contrary, individuals in one-person households without children are around two times more likely than those in families with two adults, and these differences are consistent across all model specifications.

Results of this final step of the analysis have shown the social stratification of housing deprivation risk in the Irish context. Even after accounting for human capital, regional, and tenure differences, the groups who are particularly disadvantaged are individuals aged 18–34 compared to older individuals; individuals with a disability compared to individuals without a disability; and individuals in one-person households compared to individuals in two-adults household arrangements.

6 Discussion

This article set out to study housing inequalities in two dimensions of housing, namely discrimination in access to housing and the quality of housing. Specifically, the key contribution of this manuscript to housing literature is the evaluation of whether social groups that are disadvantaged in one dimension of housing are also disadvantaged in the other dimension.

Concerning housing discrimination, existing literature suggests two main mechanisms for discrimination: taste-based discrimination, according to which the potential landlord, seller or estate agent discriminate against people who do not belong to their own social group; and statistical discrimination, where the potential landlord, seller or estate agent infer the trustfulness of the client based on the stereotypes associated to the groups the client belongs to. Our results support the existence of discrimination for traditionally vulnerable groups, namely young individuals, lone parents, people with a disability and non-natives are more at risk of discrimination while looking for housing or accommodation. Unfortunately, however, the data at hand do not permit to identify which discrimination mechanism (taste-based or statistical) is at play.

Our results are only partially in line with existing experimental literature on housing discrimination. On the one hand, contrary to existing research set in our same context (Flage, 2018; Gusciute et al., 2020) and in others (Ghekiere et al., 2022), we do not find gender differences in the experience of discrimination; on the other hand, we confirm inequality based on nationality as repeatedly found by existing research (Auspurg et al., 2019; Ewens et al., 2014; Hanson & Santas, 2014). Unfortunately, there are very few studies that look at housing discrimination by disability or age and no studies that look at family status.

We believe that the current article provides two novel contributions to existing literature on housing discrimination. First, by resorting to self-reported discrimination in survey data, it investigates the experience of discrimination for a wide range of social groups beyond gender and nationality. Second, it goes beyond existing experimental research which, while representing a gold standard in terms of internal validity, it falls short in identifying the prevalence of housing discrimination in society. Overall, our study suggests future research to enlarge the scope of discrimination research in housing search process.

Concerning housing deprivation, existing research has shown that structurally vulnerable groups are particularly at risk of housing deprivation because they lack the economic resources needed to access good quality housing (Whelan & Maître, 2012; Watson & Corrigan, 2019). Our results are in line with past research showing that more vulnerable groups, including young individuals, people with a disability, people from new EU countries and individuals in one-person households are at a higher risk of housing deprivation.

Importantly, the disadvantage of some groups holds true also after controlling for a set of socioeconomic indicators aimed at capturing their economic resources. Such result tells us that the disadvantage of those groups is not explained by the lack of economic resources needed to access better housing conditions. Unfortunately, we are not in the position to investigate the reasons behind such inequalities in accessing good quality housing. However, one can speculate that group differences in housing deprivation which remain unexplained after controlling for economic variables could be a consequence of discrimination. In fact, people who are discriminated because of their group membership in accessing good quality housing might require to look for lower quality housing as a strategy to overcome discrimination, although having the resources to access good quality housing. This might be the case if the groups which we have identified experiencing higher risks of housing deprivation are also those at a higher risk of experiencing housing discrimination.

6.1 Triangulating Subjective Housing Discrimination and Objective Housing Deprivation

In this section, we jointly evaluate the results of the analyses on housing discrimination and deprivation for overall picture of inequality across social groups in housing in the Irish context. In particular, we are interested in the co-occurrence of subjective housing discrimination and objective housing deprivation for social groups denoted by gender, age, disability, nationality, and family status.

Two preliminary remarks derived from the analyses above must be acknowledged. First, the two phenomena show a different prevalence in the overall population in the period observed: subjective discrimination while looking for housing was a concern for around 4 per cent of the population, objective deprivation in housing conditions affected 25 per cent of the population. Second, across all social groups, differences in risk of housing discrimination are larger in magnitude than differences in risk of housing deprivation.

First, we did not observe gender differences in neither the risk of self-reported housing discrimination nor the risk of objective housing deprivation. However, we do find higher levels of discrimination and greater deprivation before income controls for lone parents who are predominantly female. Second, we observed an age gradient to the disadvantage of the younger groups both for what concerns housing discrimination and housing deprivation. However, while we found that middle aged individuals are more likely to experience housing discrimination than the elders, this same groups turned out to be shielded against housing deprivation. According to our analyses, the only group that we found to be disadvantaged both in housing discrimination and deprivation is those made up by young adults aged 18–35. The double disadvantage of this group remains even after controlling for socioeconomic conditions, context, and tenure characteristics. Third, we found evidence of a double disadvantage associated with disability: individuals with a disability were found to have stronger risk of experiencing both housing discrimination and housing deprivation. Also in this case, the double disadvantage is not accounted by compositional differences in correlates of housing outcomes between individuals with and without a disability. Fourth, we observed a clear divide in the association of nationality with both housing discrimination and housing deprivation. On the one side, individuals with UK, or New EU nationalities were found to be not disadvantaged for both outcomes compared to Irish citizens. Rather, New EU citizens are even less likely to be deprived as compared to Irish citizens, which might be due to their greater location in newer build housing. On the contrary, individuals with Old EU and Non-EU nationalities were found to be disadvantaged for both outcomes. However, the observed differences are largely due to compositional differences in other correlates, namely socioeconomic, contextual and tenure conditions. In sum, Old EU and Non-EU citizens are doubly disadvantaged but this is largely due to differences in economic prospects, location, and housing market. Fifth, for family status we found that individuals in two-adults arrangements are shielded against discrimination and deprivation in housing. Instead, single individuals (lone parents and individuals in one-person households) are disadvantaged in both outcomes, thus being doubly disadvantaged. However, when accounting for compositional differences lone parents are still more likely to be discriminated but not housing deprived; on the contrary, individuals in one-person households are doubly disadvantaged even after controlling for socioeconomic status and contextual characteristics; and only when considering the different distribution in housing tenures lone parents are no more disadvantaged in housing deprivation.

All in all, considering the co-occurrence of inequalities we identify four groups, that are simultaneously discriminated and deprived: young adults, individuals with a disability, lone parents and childless singles.

6.2 Concluding Remarks

Being discriminated in the housing search process and experiencing inadequate dwelling conditions are two forms of disadvantage of utmost importance in housing studies. Several works in different geographical contexts separately look at the two phenomena, often times speculating that discrimination might be a driver of subsequent deprivation. What is more, these two negative conditions are the result of special needs or impairments encapsulated in sociodemographic characteristics such gender, age, disability, ethnicity, and household structure. In this contribution, focusing on the Irish context in the decade 2004–2015, we investigate the extent to which these conditions cooccur across social groups, triangulating subjective and objective indicators from two individual level data sources. We indeed document that there is a not straightforward association between the two conditions: some groups such as those with foreign nationality are discriminated against in the housing process, but they do not end up in low quality dwelling more often than natives; other groups such as young adults, people with disabilities or single-headed households are doubly disadvantaged, as they experience both housing discrimination and housing deprivation.

In this contribution we have established a certain degree of correspondence between housing discrimination and deprivation across population groups. However, while we can conclude that the groups which experience discrimination also tend to experience deprivation, we cannot say whether individuals who experience discrimination also experience deprivation, and to what extent. An important limitation of this study derives for the lack of data providing information on both housing discrimination and deprivation for the same individual or household. Further research should address this problem of data limitation to confirm, and better evaluate, the association between discrimination and deprivation.

Furthermore, more research is needed to better understand the dynamics in place. In particular, longitudinal data would be necessary to disentangle patterns of inequality in housing transitions (Ayala Navarro, 2007). In this case, isolating the unique role of housing discrimination in enhancing the risk of ending up in housing deprivation could be possible. More broadly, a closer investigation of mechanisms linking discrimination and further outcomes in the housing sphere is needed.

While our case study is the post housing crash Ireland, the topic under investigation is still relevant for Ireland as well as for many other Western countries. In fact, European countries, but also the US, are now facing a severe housing crisis characterised by housing shortage and affordability problems. This can only worsen the situation of vulnerable groups putting them at risk of experiencing even higher discrimination and deprivation in housing. Further research is needed to investigate the prevalence and correspondence between housing discrimination and deprivation in countries other than Ireland and in more recent periods of time.

Notes

In some studies, also tenure unstable conditions and unaffordability of rental costs are considered part of housing deprivation. In this study, we consider these characteristics as not directly belonging to housing deprivation. See Palvarini and Pavolini (2010) for a discussion of different definitions of housing deprivation.

Other items included in the factor analysis but which do not load on our factor are “Number of rooms available to the household” and “Dwelling type”.

Some of those renting privately will be in receipt of housing payments from the State, through the Rent Supplement scheme operating at the time. Those renting from voluntary housing associations are included with the local authority renters.

The circular distinguishes also the situation of non-Irish nationals with an Irish citizen spouse/civil partner.

References

Abramova, O. (2024). Discrimination on sharing economy platforms: A systematic review of cases and coping strategies. Journal of Business and Management Studies, 6(3), 69–84.

Aliu, I. R. (2024). Gender, ethnicity and residential discrimination: Interpreting implicit discriminations in Lagos rental housing market. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 39(1), 77–102.

Arrow, K. J. (1972). Gifts and exchanges. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 1(4), 343–362.

Auspurg, K., Hinz, T., & Schmid, L. (2017). Contexts and conditions of ethnic discrimination: Evidence from a field experiment in a German housing market. Journal of Housing Economics, 35, 26–36.

Auspurg, K., Schneck, A., & Hinz, T. (2019). Closed doors everywhere? A meta-analysis of field experiments on ethnic discrimination in rental housing markets. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(1), 95–114.

Ayala, L., & Navarro, C. (2007). The dynamics of housing deprivation. Journal of Housing Economics, 16(1), 72–97.

Baldini, M., & Federici, M. (2011). Ethnic discrimination in the Italian rental housing market. Journal of Housing Economics, 20, 1–14.

Barrett, A., McGinnity, F., & Quinn, E. (Eds.). (2017). Monitoring report on Integration 2016. ESRI/The Department of Justice and Equality.

Bayer, P., Casey, M., Ferreira, F., & McMillan, R. (2017). Racial and ethnic price differentials in the housing market. Journal of Urban Economics, 102, 91–105.

Becker, G. (1957). The economics of discrimination. University of Chicago Press.

Bond, L., McGinnity, F., & Russell, H. (2010). Introduction: Making Equality Count. In L. Bond, F. McGinnity, & H. Russell (Eds.), Making Equality Count: Irish and International Research Measuring Equality and discrimination. Liffey.

Borg, I. (2015). Housing deprivation in Europe: On the role of rental tenure types. Housing Theory and Society, 32(1), 73–93.

Bosch, M., Carnero, M. A., & Farré, L. (2010). Information and discrimination in the rental housing market: Evidence from a field experiment. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 40(1), 11–19.

Christensen, P., & Timmins, C. (2022). Sorting or steering: The effects of housing discrimination on neighborhood choice. Journal of Political Economy, 130(8), 2110–2163.

Christensen, P., & Timmins, C. (2023). The damages and distortions from discrimination in the rental housing market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 138(4), 2505–2557.

Clair, A., Reeves, A., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2019). Constructing a housing precariousness measure for Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(1), 13–28.

Clapham, D., Foye, C., & Christian, J. (2017). The concept of subjective well-being in housing research. Housing Theory and Society, 35(3), 261–280.

Corrigan, E., Foley, D., McQuinn, K., O’Toole, C., & Slaymaker, R. (2019). Exploring affordability in the Irish housing market. The Economic and Social Review, 50(1), 119–157.

Cross, R. I., Huỳnh, J., Bradford, N. J., & Francis, B. (2023). Racialized housing discrimination and population health: A scoping review and research agenda. Journal of Urban Health, 100(2), 355–388.

CSO (Central Statistics Office). (2007). Census 2006 volume 6 – housing. Central Statistics Office.

CSO (Central Statistics Office). (2017a). Census of Population: Profile 1 housing in Ireland. Central Statistics Office.

CSO (Central Statistics Office). (2017b). Survey on Income and living conditions, 2015. Central Statistics Office.

CSO (Central Statistics Office). (2023). Residential Property Price Index March 2023. Central Statistics Office.

DECLG (Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage) (2012). Circular Housing 41/2012 - Access to Social Housing Supports for non-Irish nationals.

Dill, V., & Jirjahn, U. (2014). Ethnic residential segregation and immigrants’ perceptions of discrimination in West Germany. Urban Studies, 51(16), 3330–3347.

Dion, K. L. (2001). Immigrants’ perceptions of housing discrimination in Toronto: The Housing New canadians Project. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 523–539.

Egan, P., & McQuinn, K. (2022). Examining the response of house prices to supply using a Markov regime switching approach: The case of the Irish housing market. ESRI Working Paper, 732. Dublin: ESRI.

Ewens, M., Tomlin, B., & Wang, L. C. (2014). Statistical discrimination or prejudice? A large sample field experiment. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(1), 119–134.

Flage, A. (2018). Ethnic and gender discrimination in the rental housing market: Evidence from a meta-analysis of correspondence tests, 2006–2017. Journal of Housing Economics, 41, 251–273.

Fumarco, L. (2017). Disability discrimination in the Italian rental housing market: A field experiment with blind tenants. Land Economics, 93(4), 567–584.

Galster, G. C. (1992). Research on discrimination in housing and mortgage markets: Assessment and future directions. Housing Policy Debate, 3(2), 637–683.

Ghekiere, A., Martiniello, B., & Verhaeghe, P. P. (2022). Identifying rental discrimination on the flemish housing market: An intersectional approach. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 46(12), 2654–2676.

Greenberg, D., Gershenson, C., & Desmond, M. (2016). Discrimination in evictions: Empirical evidence and legal challenges. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 51, 115.

Gusciute, E., Mühlau, P., & Layte, R. (2020). Discrimination in the rental housing market: A field experiment in Ireland. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(3), 613–634.

Hanson, A., & Hawley, Z. (2011). Do landlords discriminate in the rental housing market? Evidence from an internet field experiment in US cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 70, 99–114.

Hanson, A., & Santas, M. (2014). Field experiment tests for discrimination against hispanics in the US rental housing market. Southern Economic Journal, 81(1), 135–167.

Hearne, R., & Walsh, J. (2021). Housing assistance and discrimination: A scoping study on the Housing Assistance Ground under the Equal Status acts 2000–2018. IHREC.

Heylen, K. (2023). Measuring housing affordability. A case study of Flanders on the link between objective and subjective indicators. Housing Studies, 38(4), 552–568.

Higher Education Authority (2019). Eurostudent Survey VII: report in the Social and Living Conditions of Higher Education students in Ireland 2019.

Higher Education Authority (2015). Report on Student Accommodation Demand and Supply.

Hoke, M. K., & Boen, C. E. (2021). The health impacts of eviction: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health. Social Science & Medicine, 273, 113742.

Howden-Chapman, P., Bennett, J., Edwards, R., Jacobs, D., Nathan, K., & Ormandy, D. (2023). Review of the impact of housing quality on inequalities in health and well-being. Annual Review of Public Health, 44, 233–254.

Ihlanfeldt, K., & Mayock, T. (2009). Price discrimination in the housing market. Journal of Urban Economics, 66(2), 125–140.

IHREC (Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission) (2017). Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission Annual Report 2016.

Kennedy, P., & Winston, N. (2019). Housing deprivation. Absolute poverty in Europe (pp. 137–158). Policy.

Lafferty, P., & McCormack, K. (2015). A Review of the Sampling and Calibration Methodology of the Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) 2010–2013.

McGinnity, F., & Kingston, G. (2017). An Irish welcome? Changing Irish attitudes to immigrants and Immigration: The role of recession and immigration. The Economic and Social Review, 48(3), 253–279.

McGinnity, F., Grotti, R., Kenny, O., & Russell, H. (2017). Who experiences discrimination in Ireland? Evidence from the QNHS Equality modules. ESRI and The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (IHREC).

Miao, J., & Wu, X. (2023). Social consequences of Homeownership: Evidence from the Home Ownership Scheme in Hong Kong. Social Forces, 101(3), 1460–1484.

Nolan, B., & Winston, N. (2011). Dimensions of housing deprivation for older people in Ireland. Social Indicators Research, 104(3), 369–385.

Norris, M., & Domański, H. (2009). Housing conditions, states, markets and households: A pan-european analysis. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 11(3), 385–407.

O’Toole, C., Allen-Coghlan, M., & Martinez-Cillero, M. (2019). The RTB Rent Index, quarter 4 2018, Indices Report 2018Q4. RTB.

Oh, V. Y., Yu, Z., & Tong, E. M. (2022). Objective income but not subjective Social Status predicts short-term and long-term cognitive outcomes: Findings across two large datasets. Social Indicators Research, 162(1), 327–349.

Osypuk, T. L., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2010). Beyond individual neighborhoods: A geography of opportunity perspective for understanding racial/ethnic health disparities. Health & Place, 16(6), 1113–1123.

Pager, D., & Shepherd, H. (2008). The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 181–209.

Palvarini, P., & Pavolini, E. (2010). Housing deprivation and vulnerability in Western Europe. In C. Ranci (Ed.), Social Vulnerability in Europe (pp. 126–158). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Rafferty, A. (2020). Skill underutilization and under-skilling in Europe: The role of workplace discrimination. Work Employment and Society, 34(2), 317–335.

Rosen, E., Garboden, P. M., & Cossyleon, J. E. (2021). Racial discrimination in housing: How landlords use algorithms and home visits to screen tenants. American Sociological Review, 86(5), 787–822.

Rosenblatt, P., & Cossyleon, J. E. (2018). Pushing the boundaries: Searching for housing in the most segregated metropolis in America. City & Community, 17(1), 87–108.

Ross, S. L., & Turner, M. A. (2005). Housing discrimination in metropolitan America: Explaining changes between 1989 and 2000. Social Problems, 52(2), 152–180.

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright Publishing.

Safi, M. (2010). Immigrants’ life satisfaction in Europe: Between assimilation and discrimination. European Sociological Review, 26(2), 159–176.

Small, M. L., & Pager, D. (2020). Sociological perspectives on racial discrimination. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(2), 49–67.

Watson, D., & Corrigan, E. (2019). Social housing in the Irish housing market. The Economic and Social Review, 50(1), 213–248.

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2012). Understanding material deprivation: A comparative European analysis. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(4), 489–503.

Yang, T. C., Chen, D., & Park, K. (2016). Perceived housing discrimination and self-reported health: How do neighborhood features matter? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(6), 789–801.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge that the original research on which the paper is based was funded by the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Trento within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grotti, R., Russell, H., Maître, B. et al. The Experience of Housing Discrimination and Housing Deprivation Across Social Groups in Ireland. Soc Indic Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03438-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03438-0