Abstract

Social outcomes from conservation and development activities on a local scale are often assessed using five livelihood assets—Natural, Physical, Human, Financial and Social—and their associated indicators. These indicators, and the variables used to measure them, are typically based on ‘common practice’ with limited attention being paid to the use of alternative indicators. In this article, we present a typical survey of socioeconomic benefits for ecological restoration workers in South Africa, and ask whether the common livelihood indicators used are adequate and sufficient, or whether any relevant indicators are missing. Results from the livelihood survey show the value of income, food and education as strong indicators of financial and human assets, and the importance of open-ended questions in eliciting details of workers’ perceived changes in their livelihoods. However, by complementing the survey results with qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and stakeholder workshops, we show how unconventional livelihood indicators and aspects provide a deeper understanding of changes in livelihoods that are tied to restoration projects. We guide scholars and practitioners to advance their process of selecting livelihood indicators, in particular to include three additional types of indicators: intangible indicators to assess life quality; relative indicators reaching across spatial and temporal scales to capture community outcomes and livelihood resilience; and, political indicators to uncover causal relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The sustainable rural livelihoods framework, perhaps most famously as proposed by Scoones (1998), has been widely applied in various geographical contexts in recent decades as a way to assess social outcomes from conservation and development activities (Sarker et al., 2019; Scoones, 2015). The popularity of this framework goes together with the increasing interest in using sustainability indicators for evaluating the outcomes of such projects, which was already noticed some years ago (Agol et al., 2014). For instance, livelihood frameworks are applied in relation to those who earn a living through the exploitation of natural resources such as forests (e.g. Adams et al., 2016; Barnes et al., 2017), marine life (Masud et al., 2015), or minerals (Horsley et al., 2015). Livelihood approaches are also being used to assess social outcomes stemming from climate change mitigation and adaptation projects (Atela et al., 2015; Reed et al., 2013).

When applying a livelihood perspective,Footnote 1 many scholars and practitioners focus on the five so-called ‘livelihood assets’ or forms of capital, namely the Natural, Physical, Financial, Human and Social. These commonly used assets are assessed by means of a range of indicators, which ultimately determine the kind of data that is collected to assess livelihood vulnerabilities and outcomes. Despite their wide and broad applications, until recently only a few livelihood studies critically reflect on their particular choice of indicators (e.g. Horsley et al., 2015). Some of these scholars take their reflections a step further and develop novel indicators based on participatory approaches (Belcher et al., 2013) or on context-specific literature combined with the evaluators’ own extensive experience (Pandey et al. 2017). We contribute to these valuable studies by explicitly evaluating how commonly used livelihood indicators work in practice and how the process of selecting indicators can be improved. Research of this kind is important to explore the adequacy of such indicators, since they are still uncritically used in many livelihood assessments despite of their known limitations (see Sect. 2).

Scoones (2015) claims that there is no right way of assessing livelihood outcomes. However, we would argue that there might be wrong ways of assessing livelihoods if the validity of the data is compromised. This could happen if, for instance, the indicators used to assess people’s vulnerabilities and outcomes were discordant with the realities on the ground because the indicators were drawn solely from literature. Then we would risk making ‘wrong’ assessments and ultimately mismanage well-meaning interventions by potentially overlooking relevant indicators that would have captured important benefits, costs, changes or challenges.

In this article, we first present a typical livelihood survey applied in practice and then evaluate the applied livelihood indicators. We do this with the overall aim to suggest concrete ways to improve livelihood assessments by proposing guidelines for selection of more accurate and relevant indicators, which can provide a deeper understanding of actual sustainable livelihood strategies and outcomes. As our empirical example, we draw on a livelihood study from South Africa. Here different public programs have been initiated to provide a basic income for people from poor communities by employing them as workers in ecological restoration projects with the aim of improving water quality and quantity while alleviating poverty (McConnachie et al., 2013; Zabala & Sullivan, 2018). Our study investigates the various socioeconomic outcomes for workers involved in such restoration projects. A questionnaire structured around livelihood assets was developed as part of a larger research project with the overall aim of exploring the socio-economic benefits of Ecological Infrastructure (EI). The questionnaire was used in early 2019 to collect data in Western Cape, and the same questionnaire was planned to be applied in Kwa-Zulu Natal (KZN) in late 2019 and early 2020. However, as we planned our data collection in KZN, we decided to broaden the existing focus on worker’s socioeconomic outcomes by conducting a critical evaluation of the typical livelihood indicators used in our questionnaire. While the livelihood questionnaire remained unchanged from its original version to ensure consistency and to evaluate the performance of typical indicators, we added new types of qualitative data (from stakeholder workshops and semi-structured interviews) and reframed our subsequent analysis. Specifically, we address the following three questions:

How do typical livelihood indicators perform in practice?

Which indicators are missing and should be included?

How can improve our selection of livelihood indicators to better capture livelihood outcomes and vulnerabilities in dynamic settings?

Based on our findings we suggest that alternative indicators and perspectives need to be considered when livelihood indicators are developed, applied and analyzed for social assessments. With our concluding recommendations and guidelines, we contribute to important conceptual and practical advancements of commonly used livelihood approaches towards greater accuracy and relevance thereby increasing the practical usability of the approach.

2 Conceptual Framework: Livelihood Assets, Their Indicators and Associated Variables

Analyzing livelihood vulnerabilities and changes is often rooted in the popular sustainable rural livelihood framework introduced by Ian Scoones in 1998. The framework included four specific assets (Natural, Economic/Financial, Human, and Social) and a peculiar category called “and others”. Several scholars use the term ‘capitals’ instead of ‘assets’ and some add at least one more to Scoones’ original four, e.g. Physical assets or Cultural capital (Scoones, 2015).Footnote 2 Among the many graphic representations of the original framework is a simplified and commonly used diagram, namely a central asset pentagon (Fig. 1) that has been widely used for visual presentations of comparative qualitative measures (e.g. Belcher et al., 2013; Liu & Xu, 2016; Manlosa et al., 2019; Pandey et al., 2017).

A typical illustration of a livelihood framework (DFID, 1999)

Despite the appealing look and popular graphic features of the livelihood framework and its assets, the assets are difficult to operationalize in practice. They often provide only a snapshot in time and place, potentially missing important temporal and spatial aspects. Hence, a typical livelihood analysis focuses on the short-term rather than longer term dynamics, making it applicable mostly in a relatively stable context (Sarker et al., 2019). Also, the livelihood literature tends to focus on the individual, household and community scales (Horsley et al., 2015) and less on macro-scale structures and processes (Sarker et al., 2019), such as the impact of global markets and politics, which are often ‘dumped in a box labelled “contexts”’ (Scoones, 2009, p. 181). Similar simplifications have led to several misapplications and misinterpretations, which partly explains why analyses based on livelihood frameworks are accused of being apolitical (Scoones, 2009).

In this article, we focus specifically on the indicators, which are the proxies used to assess the livelihood assets, e.g., education or health as indicators of the Human asset. Such indicators are measured by different variables, such as the percentage of school enrolment. Examples from the existing livelihood literature show a range of typical indicators and associated variables used to assess these quantitatively (e.g. Berchoux et al., 2019; see Table 1). In addition to amount, percentage, ratio and distance (the main units generally used), assessment methods also rely on a scoring of variables on a Likert scale (e.g. Sharifi et al., 2019) or use a combination of measurement methods, as in the study presented in this article.

Just like the livelihood framework, livelihood indicators have been subject to criticisms. Horsley et al. (2015) argue that many studies do not mention any formal criteria for selecting indicators and that several project reports simply address the auditing needs of the sponsoring organizations. Many assessments end up relying on existing data sources, because detailed measurements are costly, time-consuming, and logistically difficult to obtain (Agol et al., 2014). The Social capital in particular and its common indicators, such as networks and norms (e.g. trust) have even been called ‘notoriously difficult to identify and assess’ (Bebbington, 1999, p. 2036). Alternative social indicators have been proposed, for instance by Pandey et al. (2017) who have developed a novel indicator to assess how many households receive help from their social networks or provide help to others. However, ‘help’ is a highly normative and personal indicator, potentially subject to a strong bias due to sensitive self-reporting of one’s needs and status in the respective community (Saito-Jensen et al., 2014). Nevertheless, this indicator can be identified based on area-specific literature and the researchers’ own extensive experience (Pandey et al., 2017), indicating that some studies do take more advanced steps to identify and select livelihood indicators in the attempt to align the conceptual with the practical challenges. The livelihood framework is also accused of not incorporating intangible indicators (Scoones, 2015) or more institutional indicators such as rights and governance (cf. Scoones, 2009, see however Odour, 2020). These and other political aspects are often largely missing (Bebbington, 1999; Sallu et al., 2010), including a critical focus on social access and on attention to the “wealthier” players, whose role is neglected by a focus on the “poor” (Small, 2007). Thus, when applying a livelihood approach in a given context, scholars or practitioners might fail to address why people’s capacities are as they are (Ribot, 2014). For instance, livelihood assets and indicators might be used to explain why people engage in different livelihood strategies (e.g. Pour et al., 2018), but few studies attempt to explain what underlying factors shape different assets, even when recommendations are made to improve these same assets by various means related to the indicators being assessed.

We argue that it is necessary to keep in mind how Scoones (2009) more than a decade ago proposed a somewhat continuous process for improvement of the approach:

‘Planning for and implementing a sustainable livelihoods approach is therefore necessarily iterative and dynamic. [It] requires the active participation of all different interested parties in the processes of defining meanings and objectives, analysing linkages and trade-offs, identifying options and choices and, ultimately, deciding what to do.’ Scoones (2009, 15)

Many livelihood studies fail to follow Scoones’ pledge for several reasons that we will return to in our discussion. As we recap and evaluate our own livelihood approach using an empirical study from South Africa, we provide reflections and encourage others to do the same. Specifically, we deconstruct the central components of livelihood frameworks—namely the assets—and provide a fresh look at the livelihood indicators and the criticisms surrounding them.

3 Methodology: A Livelihood Outcomes Study from South Africa

The livelihood indicators assessed in our study build on two existing and connected studies. In their global review, Rasmussen et al. (2021) provide an extensive overview of the socioeconomic outcomes of Ecological Infrastructure (EI) interventions across geographical regions. The authors identify bundles of positive outcomes, including Justice, Social relations, Property rights, Income, Food security, Health, Education, Employment, Material assets and Natural capital. Most of these bundles thereby correspond directly with some of the typical livelihood assets and indicators shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. For South Africa specifically, the authors show that a large proportion of studies focus on the outcomes of EI interventions in relation to Income, Natural capital and Employment, Social relations, Material assets and Education, but with little or no focus on the remaining bundles of socioeconomic outcomes, which are all more political. Notably, across their dataset, the authors find relatively few studies presenting negative or socially differentiated outcomes, pointing to an important research gap. A study by Olesen et al. (2021) takes point of departure in the review and develops a survey to assess the multiple dimensions of livelihood and well-being among ecological restoration workers in South Africa (Western Cape). The survey questionnaire was designed to capture the expected socio-economic benefits for EI workers, benefits that correspond to common assets and indicators used in livelihood studies, but including questions to capture socially differentiated outcomes and the political aspects of decision-making.

In our study, we evaluate the performance of the abovementioned livelihood indicators to explore their contextual suitability and conceptual adequacy rather than testing our findings to provide statistical generalizations for a wider population, as most studies do. Instead we ask whether the indicators seem sufficiently applicable to local settings, whether important indicators or aspects are missing and whether they capture relevant aspects of change. As these are highly normative questions (what is sufficient, adequate, and relevant, and to whom?), the criteria for our evaluation are tied to the livelihood critique presented in terms of indicator selection, scales, and causality. Based on our findings and reflections, we suggest how livelihood studies—in particular indicator selection—can be improved (Sect. 5).

3.1 Study Site and Data Collection: Survey, Interviews, and Workshops

South Africa is facing immense environmental and hydrological problems related to the spread of invasive alien plant species (IAPS), which has accelerated over the past few decades (Rashid & Siphokuhle, 2020). Public programs for the eradication of IAPS have been established to restore important ecosystem services such as water and biodiversity, including Working for Water (WfW) and Working on Fire (WoF). Among several related initiatives, these programs jointly address poverty alleviation and wetland restoration by employing restoration workers from local poor communities (McConnachie et al., 2013; Neely, 2010; Zabala & Sullivan, 2018). WoF requires more demanding physical activities and therefore training, as these workers are tasked to manage fire and undertake IAPS control in less accessible terrain (Roberts et al., 2012). The criteria for recruitment to WoF teams therefore differ from WfW in terms of age groups and the skills required, and WoF workers are often employed on longer term contracts extending over years rather than months (personal communication, WoF project manager, February 2020). Previous studies have assessed various livelihood outcomes for restoration workers, such as acquisition of skills and employability (Rashid & Siphokuhle, 2020; Roberts et al., 2012; Zabala & Sullivan, 2018), indicating a environmental and social net-worth of such approaches to both control IAPS and alleviate poverty (Rashid & Siphokuhle, 2020).

The data used in this article was collected through a livelihood survey of WfW and WoF workers in November 2019 and February 2020 in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province (Nworkers = 181). Eight workers in total had experience from other restoration programs, and these experiences were also recorded (Nprojects = 189). The survey was conducted at accessible meeting points in the Howick and Wartburg areas, and in the Drakensberg Mountains. The workers, typically organized in teams of 10–12, were purposefully sampled based on feasibility. The teams were identified and selected by contacting a regional manager, who knew where the local teams were working and allowed for their time spent on the survey. All workers in each team visited were surveyed.

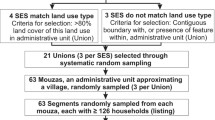

The questionnaire was centered around issues concerning workers’ socioeconomic backgrounds, their motivations for engaging in the project and the benefits they receive from it. These benefits were structured around typical livelihood assets and associated indicators, namely Financial (income, employment), Physical (electricity, cooking and heating facilities, communication devices, access to water), Human (health, in particular food, and education, including environmental awareness and skills), Natural (fertile soil, forest resources), Social (networks, organizations) and Political (decision-making and the distribution of benefits). The majority of the questions were closed-ended, but some with open-ended options to capture individual answers or provide opportunities to specify. Questions regarding perceived improvements in livelihood assets were recorded using a Likert scale. Survey responses were collected by local enumerators (speaking isi-Zulu or English) and by the first author (in English) on Tablets loaded with Qualtrics software. Consent forms were filled out by each worker before the survey started. The results were organized and analyzed in MS Excel for the quantitative data and in Nvivo 12 software for qualitative analysis through thematic coding. Simple percentage calculations of how the livelihood benefits from the restoration projects were perceived by the workers were calculated and are presented in diagrams (Fig. 2).

Examples of socioeconomic benefits for restoration workers involved in EI interventions. The diagrams show how the restoration projects affect workers’ household’s incomes (2a), and how the income from the project affects different aspects of the workers’ household’s livelihoods in terms of different assets measured, for instance, (2b) household health, (2c) access to education (e.g. income used to pay school fees, uniforms) and (2d) environmental awareness. Nprojects = 189. This figure includes eight surveys completed by workers involved in two projects, meaning that Nworkers = 181

Workers are organized into teams led by a contractor or supervisor, who is responsible for organizing the transport, alien plant clearing (tools, herbicide, safety, etc.) and salary payment in accordance with a contract made with the project manager. The project manager is responsible for overseeing the planning and implementation of the projects within a particular region (cf. McConnachie et al., 2013). Semi-structured interviews with twelve WfW contractors, two supervisors (private land and WoF), two managers (WfW and WoF) and one project coordinator (organizing WfW teams) were conducted by the authors in English. Questions primarily concerned the tasks they perform and the challenges and opportunities they face. One spontaneous interview at a local Community Hall with a Social Counsellor Assistant was conducted by the first author. In addition, two stakeholder workshops (29 and 33 participants, respectively) were held with representatives of local authorities, research institutions, restoration project managers, local landowners, and non-governmental organizations. The data used originate from a session facilitating and summarizing discussions regarding the intangible benefits for the restoration workers and how to assess them. All the data were anonymized, stored, and handled in line with the relevant ethical regulations.

4 Results and Analysis: Livelihood Indicators and Assessment of Benefits for Ecological Restoration Workers

4.1 Livelihoods Outcomes Based on Indicators

In the following, the workers’ percieved outcomes from the EI restoration are analysed around the five livelihood assets and are assessed by means of typical livelihood indicators. We take departure in the Financial assets, measured by income and employment, as a central benefit connected to the other livelihood improvements. As we reflect upon our use of the indicators, we discuss how well they capture livelihood changes and whether they are suitable in the particular local context.

Income appears to be a very strong indicator, especially when it is specified in terms of people’s actual use of the money earned through the EI project and when compared to the workers’ previous income situations. Approximately 85% of workers felt that the EI project has ‘greatly improved’ or ‘improved’ their household incomes, while about 13% felt no effect (Fig. 2a). Only two workers feel a ‘moderate decrease’ or ‘great decrease’, since their present salary is considered low in general or relatively low when compared to their previous involvement in EI projects. Many workers spend their project incomes on groceries and their childrens’ schooling, on paying for clothes and on paying debts, insurance and hospital bills. While this sounds promising, the livelihood survey also shows that for many workers their economic situation is still critical in terms of their few sources of income and their many dependents (measured here as children under fifteen years old, combined with a low number of other income-earning people in the household). Likewise, an open-ended question to determine perceived changes in income reveals how several workers previously lived only on pensions or other social grants (e.g. for small children), and that the money earned might still not be enough to secure their basic needs, like daily meals.

Indeed, food was shown to be an extremely valuable and strong indicator in the survey, as it was easy to explain and relate to. The responses were equally clear: when workers rank their top-three purchases from project income, food was ranked first by 143 out of 189 workers (of whom eight had participated in two EI projects and thus evaluated both). Interviews with contractors confirm these main benefits for the workers, emphasizing their ability to become ‘breadwinners’ in their families and support their children’s education.

Several other indicators were intuitive, providing responses with useful information about the workers’ experiences and perceived livelihood changes. Figure 2b–d convincingly show improvement in the workers’ Human asset, as indicated by better household health and education. The effects of the project on household health specifically as an indicator of Human assets showed that almost half the number of workers surveyed feel ‘great improvements’ (Fig. 2b), which can most likely be traced back to food expenses and hospital bills. Household education was also perceived to have improved to a great or moderate extent, with only 17% feeling no effects (Fig. 2c). Another aspect of education, namely the environmental awareness of the EI workers, has improved to a great extent according to eight out of ten workers (Fig. 2d). In terms of skills and competencies (also connected to changes in the Human asset as an educational indicator), close to eight out of ten (77%) of the workers feel there have been ‘great improvements’. Our survey responses show that workers acquire skills ranging from first aid and other safety measures (e.g., handling snakes, fire, and herbicides) to knowledge about the value of water, animals, and the differences between indigenous and alien plant species. Interestingly, the interviews with contractors reveal mixed opinions about the importance of these acquired skills and knowledge for the workers: some contractors claim that such competencies provide better job opportunities, while others claim that they are useless for other positions.

Perceived changes in the workers’ Physical assets show patterns similar to those presented in Fig. 2 (primarily great to moderate improvements), namely in the workers’ means of transportation and communication, as well as their cooking and heating facilities. Effects on sanitation facilities seemed hard for workers to connect directly to the project, and the results show primarily ‘moderate improvements’ (33%) or ‘no effects’ (46%). Sanitation and electricity in rural areas fall under community development and are not issues that individual households can always improve on their own. Social assets measured by workers’ households’ involvement in networks and organizations or groups showed moderate to great improvements (75% and 68%, respectively). However, these indicators were to some extent self-explanatory, as the workers were part of a project team with whom they spent considerable time and became acquainted.

The indicators of workers’ access to soil and forest for timber and access to non-forest products were assessed as indicators of Natural assets. We found that questions about access to forest and fertile soil were rather meaningless, as the workers do not own or manage any substantial land areas or live near forests, apart from private timber concessions or state-owned protected areas. This mismatch with local realities is reflected in responses showing almost eight out of ten feeling no effect on their access to soil or forest. Access to water is particularly interesting for these kinds of restoration projects, since the main environmental aim is to improve the quality and quantity of water (Sect. 3). However, the survey data indicates that workers primarily experience no effects on their access to clean water (58%), an issue to which we return in Sect. 4.2.

Interestingly, most of the workers do feel that they participate in decisions concerning the actual project work (decision-making as an indicator of Political assets). More than three out of four workers (76%) state that they are always or sometimes involved in decisions about the project, for example, about the type of work to be done and about solving any problems that arise; less than one in four (23%) feel that they are never involved. This latter sub-set is spread out across age groups, gender, and teams, which indicates that internal group dynamics or hierarchies could be the underlying reason, an aspect we explore further in the following section.

4.2 Beyond the Direct and Tangible Outcomes

We now turn to our findings primarily stemming from other types of data (from stakeholder workshops and semi-structured interviews) that take our analysis beyond the typical livelihood indicators and variables used in our survey questionnaire.

4.2.1 Knowledge Spillover

As mentioned above, workers often must travel considerable distances, a majority between thirty and sixty minutes by minibus, to get to their actual worksite. This might lead to the conclusion that the workers’ home communities do not benefit from their clearing of alien species for improved water quantity and quality. However, an open-ended question about the household’s skills and competencies revealed a somewhat unexpected outcome: twelve workers told us (without being prompted) that they bring their restoration knowledge home and that some even removed alien species at their own settlements. These workers not only taught their households or extended families how to protect the environment and make water sources safer, some also informed their neighbors. This transfer of knowledge and activities was also pronounced among the contractors: one explained that he had now learned about alien invasive species versus native species, and that he teach his children and started to remove water-intensive weeds in his spare time. Another contractor even took left-over herbicide from the project site to apply at her home. This positive ‘spill-over’ into the workers’ own communities is in line with the discussions at the stakeholder workshops, where it was suggested to focus on the workers’ children to assess changes for future generations in relation to behavior, lifestyle and the sense of community.

4.2.2 Intangible Benefits

Several other indirect and intangible benefits surfaced during the interviews or by the initiative of the interviewee during the survey, such as social respect, the love of nature, being with a lot of people, celebrations and food (during working hours), and the joy of helping out in the community (to prevent fires or save water). Such feelings indicate a sense of community and increased happiness, but typical livelihood indicators (cf. Table 1) rarely capture these benefits. At the stakeholder workshop, similar benefits were mentioned as important, for instance a sense of stewardship, a sense of purpose or meaning, dignity, and increased social cohesion. Along the same lines, some contractors displayed a strong sense of responsibility and pride in what they do, reflected in comments such as ‘getting the job done’ or ‘doing the job well’ when asked about their motivations. This corresponds to outputs from the stakeholder workshops suggesting that other livelihood indicators should be introduced to assess self-esteem, leadership, and a sense of pride through work performance.

4.2.3 Recruitment of Beneficiaries

While contractors express similar motivations, there are other variations between teams that highly shape the benefits for workers, namely in the individual contractors’ recruitment procedures. Most recruit by prioritizing ‘those in need’, meaning the poor and unemployed in their community. Some recruit by specifying certain criteria, such as education, language proficiency, or gender quotas, and some involve their team in recruiting or replacing workers. Two contractors organize their selection of workers by ‘making a list of those willing and unemployed’ or by random draw in order not ‘to do favors’. The remaining six contractors interviewed stated that they are not involved in the recruitment process, as it is the sole responsibility of the social counsellor, who follows a formal procedure based on a priority list with the profiles of potential employees or workers. This list is relies on input from the Department of Health and the Community Ward Committee, who identify those in need (interview at Community Hall, February 2020). However, this formal channel was openly criticized by two contractorsFootnote 3:

‘The counsellor will replace older workers with youth, even when the young workers don’t want to work and spend their income unwisely compared to older workers with kids. Some older workers who are laid off don’t want to leave.’

‘Initially, [workers were] selected with the counsellor, who selects friends and relatives. Now I choose my team based on needs … people sitting on the road ... anyone who needs a job and is willing.’

Recruitment procedures shape internal group dynamics of each restoration team, which again shape workers influence over projects. However, these aspects are not captured by standard survey questions about decision-making as an indicator of Political assets; they are rather revealed through other channels.

4.2.4 Distribution of Benefits

Group dynamics also seems to affect the allocation of benefits from the project. Several workers state that benefits are distributed based on people’s achievements and experience, their work ethics, their position in the community or their different home backgrounds. Some replied that ‘different kinds of treatment arise from different kinds of assigned jobs’ and that ‘some get bonuses and others don't’. Allocation of team responsibilities is particularly interesting in this regard, as contractors have very different strategies. Some make a complete division of labour within the teams (e.g. 1–2 first aiders, 1–2 health and safety representatives, one responsible for herbicide mixing, a separate supervisor). Other contractors take on the responsibility mainly as drivers and supervisors by allocating some tasks to other team members, while other contractors engage in all tasks, including the actual physical labor involved, for example removing invasive alien plants. These different roles of team members may explain the lack of shared decision-making felt by some. Even though the workers’ own perceptions of benefit sharing were not further explored through the standard survey indicators, they show the value of adding more aspects of relative positions of beneficiaries in assessments of livelihood outcomes.

4.2.5 Continuity of Projects

Lastly, a central and critical issue shaping the vulnerability and livelihood outcomes of the EI workers was emphasized during the contractor interviews: the lack of continuity of the EI projects. Eight out of twelve WfW contractors pointed to this problem without being specifically prompted (e.g. about the duration or number of project assignments). The main issue concerns the gap periods between project assignments, that can leave contractors and workers without jobs for up to four or five months. During these periods, workers struggle even more or fail to secure the benefits described above pushing some take out cash loans or seek other (very scarse) job opportunities to cover expenditures for food and their childrens' education. This results in a high turnover of workers when projects start again. Another problem with the lack of continuity is uncertainty regarding the monthly wage, since the assigned work sometimes covers only ten days a month due to bad weather or other logistical complications. The livelihood effects of these gaps are not clear from the typical survey indicators, but were summarized by an experienced contractorFootnote 4:

‘When the [projects] start and stop, they [the workers] sometimes do nothing. It harms the people. If permanent, [the employment] would be much helpful and make people live. If you help someone, don’t drop him … help him stand on his own feet and carry himself’

In contrast to complaints by several contractors, only two workers mention the lack of continuity and stability of the work (and thereby income) in the survey: one mentioned that the income changes from month to month and another stressed that there is a stop in income when the project period comes to an end. None of these statements give rise to any particular attention because the negative consequences and their magnitude are not revealed by static livelihood indicators capturing only a snapshot of peoples’ challenges. However, had the survey included previous workers (those not re-employed) or repeated during a gap period, a deeper understanding of the workers’ vulnerability and livelihood outcomes would have been acquired.

5 Discussion: Selecting Appropriate, Dynamic Livelihood Indicators

Our study reveals some of the obvious advantages of livelihood studies, for instance, by emphasizing the value of indicators that convincingly show changes to income and the strong benefits that are derived. Such results can be used to persuade public institutions and private investors to support restoration programs with social benefits to ensure continuation or even expansion of the projects (Rashid & Siphokuhle, 2020). We have also documented the value of open-ended follow-up questions in eliciting more details about the workers’ perceptions, experiences, and priorities. These details can be used to specify and nuance the more tangible, measurable livelihood outcomes. Such insights are useful in advancing the knowledge base regarding the livelihood benefits derived from ecological restoration, which can then promote communication and support arguments in favor of local involvement and empowerment.

However, even with all these advantages and potentials in mind, our livelihood survey based on commonly used indicators is far from optimal. Several of these indicators prove difficult to operationalize in practice, in particular the Natural assets in the form of water, forest, and soil, but also the Social assets, which are often reduced to engagement in networks and organizations (see Table 1). Political assets are covered by questions on benefit distribution and decision-making, but the results do not reveal why people are (not) able to benefit from or involved in decisions. Survey findings based on typical livelihood indicators might be very useful in displaying important livelihood outcomes in terms of, for instance, income and food security. However, they provide very little explanation of the temporal or spatial dynamics—and thus the long-term vulnerability and resilience—of peoples’ livelihoods. If the most typical and popular livelihood indicators are not sufficient or appropriate, how do we improve livelihood studies? Open ended survey questions and complementary interviews are extremely valuable, as shown, and should be mandatory, but rely more on the initiative of the respondents and the interviewer in a less consistent, comparable and generalizable manner.

Our findings point towards specific types of indicators and especially ways of selecting them, which could improve livelihood assessments by tying indicators more closely to the challenges and opportunities of informants, and thereby capture more critical points more consistently. We briefly summarize our points below before elaborating on each of them in the following sub-sections. Specifically, we see a need to:

-

o

Identify and select livelihood indicators by paying more attention to the local context and structures

-

o

Include

-

o

intangible indicators to capture less measurable outcomes.

-

p

spatial indicators to capture the spill-over of effects at community level

-

q

temporal indicators to capture livelihood outcomes when and if the intervention is changed or discontinue.

-

o

Assign causality and thus responsibility by asking why livelihood assets are at a certain measured level.

5.1 Selecting Contextual Livelihood Indicators

Several assessments applying a livelihood framework seem to use the same standard universal indicators (e.g. health and education as indicators of the Human asset) (Table 1). Using universal indicators is not a problem in itself, but it becomes a problem if they are applied out of (local) context or disguise underlying injustices (e.g. Pasgaard & Dawson, 2019). In this article, we show how the outcomes for restoration workers extend far beyond the commonly observed impacts on natural assets, income and employment. Combining a livelihood framework with other analytical approaches (such as governance principles, see Odour, 2020, or Common Pool Resource, see Barnes et al., 2017) does lead to a more nuanced understanding than applying a single framework alone or a single method of data collection. However, even though many livelihood studies mix and merge approaches, there are complications standing in the way of reaching useful livelihood assessments.

Conservation and development projects, including those tied to ecological restoration, are often led by experts from wealthier parts of the country or world, but involve and target less resourceful communities (Mosse, 2011; Scoones, 2015). Projects therefore run the risk of applying an imprecise understanding of local ways and needs, which ends up drowning in external scholars’ or agencies’ ‘will to improve’ the lives of others (Li, 2007). Claiming to know how others should live, what is best for them, and what they need (Li, 2007) may result in a definitive, predetermined, top-down concept of ‘development’ (Horsley et al., 2015) subject to detailed quantitative measurement. As brought forward by Small (2007) and shown in our study, livelihood frameworks often emphasize the individual or household in the development process, and are thus essentially “microeconomic in orientation” (p. 32), and they are often quantitatively measured through user-friendly indicators communicated in persuasive graphs, such as our diagrams of livelihood benefits. This “measurementality”, where the effectiveness of projects requires standardized quantifiable discrete units, is never neutral (cf. Turnhout et al., 2014)—nor is it always accurate, as our study shows. When conservation and development programs rely on social assessments based on such external standard proxies or indicators, they risk losing track of realities and in the worst case lead to mismanagement of a critical situation.

Instead, participatory development of indicators (e.g. Belcher et al., 2013; Reed & Dougill, 2002) or pilot studies to adapt surveys (e.g. Pour et al., 2018) could better tie indicators to local contexts, but such efforts are not always prioritized or possible within the time and resource constraints of a research or intervention project (Agol et al., 2014). Specific indicators might even be fixed beforehand due to certain research aims (e.g., water security) or donor demands (e.g. evidence of increased employment), leaving little room to adapt or select appropriate and possibly unconventional indicators across time and space, as argued below.

5.2 Considering Intangible Indicators and Spatio-Temporal Scales

As we have learned from a broad array of stakeholders, several intangible benefits, such as dignity and stewardship, are highly relevant and desired livelihood outcomes from EI restoration projects, but the typical and tangible indicators do not capture these benefits. Maneuvering within these constraints, livelihood studies need to ask and reflect on whether potential livelihood indicators are adequate and sufficient instead of relying blindly on typical, tangible and measurable assets, indicators and variables. Our study shows that environmental knowledge and awareness, including associated actions of water conservation and the removal of invasive species, reaches beyond the individual worker and extend into the workers’ home communities, both horizontally (to neighbors) and vertically (across generations). Such observations underline the argument of Berchoux and Hutton (2019), who suggest that forms of community capital should be distinguished from forms of individual or household capital, since they work though different dynamics. A focus on the village or community scale has the disadvantage of disguising inequality within the village (Belcher et al., 2013), while a focus on the household might disguise positive or negative ‘spill-over’ effects to the wider community. Several social scales should thus be assessed. In particular, the connection with the broader community was not explicitly probed in our survey in relation to environmental awareness. Instead, the effects on workers’ home communities appeared unexpectedly in contractor interviews and stakeholder workshops, and when we asked the workers to specify how the particular project affects their household’s skills and competences. This indicates that conventional spatially confined indicators, e.g. those stemming from an individual or household focus, do not automatically embrace the community as well. It seems crucial to include wider scalar concerns when assessing benefits derived from restoration and development projects—and livelihood sustainability in general (Scoones, 2009).

The temporal aspects are also missing in many livelihood assessments, but we document that they are essential. Other studies also point to this lack of long-term benefits for EI intervention workers and acknowledge the limitations of an approach that does not cover changes in assets over time (Olesen et al., 2021). We add to these reflections by underlining the lack of control groups, which could stem from a common bias found in livelihood studies, where assessments focus only on those who actually experience the outcomes (cf. Sarker et al., 2019). Thus, a description of variables and outcomes alone is limiting, not only because it disguises institutional structures and processes (Scoones, 2009), but also because it hides the actual vulnerabilities of the whole community over time. Amplifying temporal perspectives would extend the focus on people’s livelihood outcomes to include their resilience and transformative capacity (cf. Sarker et al., 2019), as studied by Peng and Guo (2020) for understanding the dynamics of hoursehold disater resilience in rural China.

Besides paying attention to other groups in a community, it is equally important to keep the poverty or vulnerability ‘baselines’ of those surveyed as a point of reference (Ribot, 2014; Scoones, 2015). In our study, we hear about basic food sufficiency and other essentials, and about providing jobs for people who would otherwise spend their days ‘sitting on the road’. Avoiding hopelessness and crime can be seen as a positive externality, as the workers ‘miss’ the opportunity to waste their lives or get into trouble (see also McConnachie et al., 2013). Such reference points for alternative livelihood outcomes are not captured by typical indicators, which might instead end up showing persuasive positive numbers and graphs with green-colored benefits (Fig. 2) misrepresenting the lived (in)stability and vulnerability of intended the beneficiaries. In other words, and in a relative sense, we are not talking about lifting people out of poverty, but perhaps about gradually moving some of them from deep poverty (and despair) to a different level of poverty. Importantly, this relative improvement in livelihoods might only last as long as the restoration programs run, as explained above (see also McConnachie et al., 2013). Thus, livelihood indicators should situate observed changes by asking questions that connect diverse types of outcomes to the wider community in time and place, including taking into account the existence and content of “exit strategies” for the intervention (Agol et al., 2014).

5.3 Identifying Causality and Assigning Responsibility

A stronger emphasis on causality and causal mechanisms in the assessment of socioeconomic effects of EI projects may entail a closer look at the institutions and actors that shape people’s access to benefits (cf. Ribot, 2014; Sallu et al., 2010), instead of just assessing the changing levels of the five livelihood assets. Assigning a cause indicates responsibility (Ribot, 2014) that often falls back on the implementing institutions, or it may have roots in deeper formal or informal structures and processes, such as historical dispossession or existing elite systems (e.g. McConnachie et al., 2013). We see this very clearly in our study, where the recruitment process (and thus the allocation of incomes) varies between different contractors instead of following the prescribed procedures. Even though the recruitment process is essential for the allocation of benefits, typical livelihood indicators did not capture this. Assigning responsibility for potentially unfair benefit distributions to the institutions and structures that shape them will rarely happen without the inclusion of sensitive questions to capture the “why”. Actions to address the causes seem even further away, as these same institutions may be part of the project assessments and therefore might hesitate to nuance or expand indicators in a more political direction, as they would prefer to report successes rather than failures (Saito-Jensen & Pasgaard, 2014). Thus, the apolitical nature of typical livelihood assets, if applied in isolation and out of tune with the local context, tends strongly to overlook the deeper structural and procedural conditions that shape livelihood outcomes (cf. Small, 2007). More than a decade has passed since Scoones (2009) summed up the various shortcomings of a simplified use of livelihood frameworks and suggested a more political approach, but it seems like little has changed.

5.4 A Way Forward for More Selecting More Appropriate Livelihood Indicators

Being well aware of the powerful appeal of diagrammatic representations and of the risks of simplifications, we have tied our key lessons to the livelihood framework in the hope of igniting a deeper, broader and reflexive use of its popular indicators. While it may seem counter-intuitive to focus on the indicators after all the criticisms aired in this paper, we do so because assessing indicators is a widely accepted and used method due to their appealing features. Thus, instead of inventing another new livelihood framework—or rejecting the existing frameworks all together—we propose a set of specific and actionable guiding questions to accompany its application with specific focus on the livelihood indicators (Fig. 3).

When a social assessment based on a livelihood approach is planned, the questions presented in Fig. 3 could guide researchers, students, and practitioners to start with reflections on the adequacy and sufficiency of their pre-selected indicators, typically drawn from the literature (e.g. Masud et al., 2015). They should ask themselves, local experts, and representatives of the group to be surveyed whether the envisaged indicators make sense in the local sociopolitical context (step 1) and whether any (intangible) indicators are missing (step 2). When indicators that are more proper are selected, one should keep in mind the dynamic scales and resilience of livelihood outcomes, as the approach is developed and applied. For instance, more spatial indicators should capture interactions and potential outscaling from the involved individuals to households and communities (step 2), while more temporal indicators should address people’s ability to respond to shocks and stresses over time (step 4), capturing central elements of whether livelihood changes are indeed sustainable in terms of vulnerability and adaptation capacity (Adger, 2006; Scoones, 2009). Asking why livelihood assets are at their presumed, initial, or measured level is a central question throughout the data collecting process, complementing the typical focus on the relationship between assets, strategies and outcomes (Fig. 1). All questions should be repeated at different phases of a livelihood approach in an iterative way, e.g., during a literature review, after pilot studies or analyses and, importantly, when disseminating the results. Importantly, this process of selecting indicators may be adapted and applied to other frameworks and approaches to capture for instance human-nature relations or incentives for community engagement, which work along similar types of assets.

6 Conclusion

An active and dynamic participation of all stakeholders involved in planning and implementing sustainable livelihood approaches would be ideal, but such an approach seems to lack a specific direction and guidelines, and is not feasible within the practical constraints faced by many conservation and development scholars and practitioners. Based on our study, we instead call for more context-specific, intangible, dynamic, and political indicators to avoid insufficient, superficial, static and apolitical livelihood assessments. We build this call on post-assessment evaluations and data triangulations showing how conventional livelihood indicators can indeed provide valuable knowledge, but also lead to or confirm wrongful assumptions and misinterpretations. By following—and hopefully adapting and extending our guiding questions for selecting more appropriate livelihood indicators—livelihood assessments could become more contextually and methodologically sound, while also provide more valuable results and lessons to a broader audience.

Notes

Besides social assessments and studies of impacts from conservation and development activities, we also draw upon studies of livelihood impacts stemming from changing environmental conditions to expand the methodological and theoretical lessons learned.

In this article, we use the broad terms ‘livelihood framework’ and ‘livelihood approach’ interchangeably, and we use ‘assets’ unless we are referring directly to a source using ‘capitals’.

Interview, female contractor (November 2019) and male contractor (February 2020), respectively.

Interview, male contractor, February 2020.

References

Adams, C., Rodrigues, S. T., Calmon, M., & Kumar, C. (2016). Impacts of large-scale forest restoration on socioeconomic status and local livelihoods: What we know and do not know. Biotropica, 48(6), 731–744.

Adger. (2006). Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006

Agol, D., Latawiec, A. E., & Strassburg, B. B. N. (2014). Evaluating impacts of development and conservation projects using sustainability indicators: Opportunities and challenges. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 48, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2014.04.001

Atela, J. O., Minang, P. A., Quinn, C. H., & Duguma, L. A. (2015). Implementing REDD+ at the local level: Assessing the key enablers for credible mitigation and sustainable livelihood outcomes. Journal of Environmental Management, 157, 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.04.015

Barnes, C., Claus, R., Driessen, P., Dos Santos, M. J. F., George, M. A., & Van Laerhoven, F. (2017). Uniting forest and livelihood outcomes? Analyzing external actor interventions in sustainable livelihoods in a community forest management context’. International Journal of the Commons, 11(1), 532–571.

Bebbington, A. (1999). ’Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development, 27, 2021–2044.

Belcher, B., Bastide, F., Castella, J. C., & Boissiere, M. (2013). Development of a village-level livelihood monitoring tool: A case-study in Viengkham District, Lao PDR. International Forestry Review, 15(1), 48–59.

Berchoux, T., & Hutton, C. W. (2019). Spatial associations between household and community livelihood capitals in rural territories: An example from the Mahanadi Delta, India. Applied Geography, 103, 98–111.

Berchoux, T., Watmough, G. R., Hutton, C. W., & Atkinson, P. M. (2019). Agricultural shocks and drivers of livelihood precariousness across Indian rural communities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 189, 307–319.

DFID (1999). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheet’. Department for International Development. London, UK.

Horsley, J., Prout, S., Tonts, M., & Ali, S. H. (2015). Sustainable livelihoods and indicators for regional development in mining economies. Extractive Industries and Society-an International Journal, 2, 368–380.

Li, T. M. (2007). The Will to Improve. Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Duke Univerity Press - Durham and London.

Liu, Y. H., & Xu, Y. (2016). A geographic identification of multidimensional poverty in rural China under the framework of sustainable livelihoods analysis. Applied Geography, 73, 62–76.

Manlosa, A. O., Schultner, J., Dorresteijn, I., & Fischer, J. (2019). Capital asset substitution as a coping strategy: Practices and implications for food security and resilience in southwestern Ethiopia. Geoforum, 106, 13–23.

Masud, M. M., Kari, F., Yahaya, S. R. B., & Almin, A. Q. (2015). Livelihood assets and vulnerability context of marine park community development in Malaysia. Social Indicators Research, 125, 771–792.

McConnachie, M. M., Cowling, R. M., Shackleton, C. M., & Knight, A. T. (2013). The challenges of alleviating poverty through ecological restoration: Insights from South Africa’s “Working for Water” program. Restoration Ecology, 21, 544–550.

Mosse, D. (2011) Adventures in Aidland: The Anthropology of Professionals in International Development. Berghahn Books

Neely, A. H. (2010). “Blame it on the weeds”: Politics, poverty, and ecology in the New South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 36(4), 869–887.

Odour. (2020). Livelihood impacts and governance processes of community-based wildlife conservation in Maasai Mara ecosystem, Kenya. Journal of Environmental Management, 260, 110133.

Olesen, R. S., Rasmussen, L. V., Fold, N., & Shackleton, S. (2021). Direct and indirect socio-economic benefits from ecological infrastructure interventions in the Western Cape, South Africa. Restoration Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13423

Pandey, R., Jha, S. K., Alatalo, J. M., Archie, K. M., & Gupta, A. K. (2017). Sustainable livelihood framework-based indicators for assessing climate change vulnerability and adaptation for Himalayan communities. Ecological Indicators, 79, 338–346.

Pasgaard, M., & Dawson, N. (2019). Looking beyond justice as universal basic needs is essential to progress towards ‘safe and just operating spaces.’ Earth System Governance, 2, 100030.

Pour, M. D., Barati, A. A., Azadi, H., & Scheffran, J. (2018). Revealing the role of livelihood assets in livelihood strategies: Towards enhancing conservation and livelihood development in the Hara Biosphere Reserve. Iran. Ecological Indicators, 94, 336–347.

Rashid, H., & Siphokuhle, M. (2020). Evaluating the environmental and social net-worth of controlling alien plant invasions in the Inkomati catchment, South Africa. Water Sa, 46, 54–65.

Rasmussen, L., Fold, N., Olesen, R., & Shackleton, S. (2021). Socio-economic outcomes of ecological infrastructure investments. Ecosystem Services, 47, 101242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101242

Reed, M. S., G. Podesta, I. Fazey, N. Geeson, R. Hessel, K. Hubacek, … A. D. Thomas (2013). Combining analytical frameworks to assess livelihood vulnerability to climate change and analyse adaptation options. Ecological Economics 94: 66–77.

Reed, M. S., & Dougill, A. J. (2002). Participatory selection process for indicators of rangeland condition in the Kalahari. Geographical Journal, 168, 224–234.

Ribot, J. (2014). Cause and response: Vulnerability and climate in the Anthropocene. Journal of Peasant Studies, 41, 667–705.

Roberts, D., R. Boon, N. Diederichs, E. Douwes, N. Govender, A. McInnes, … M. Spires (2012). Exploring ecosystem-based adaptation in Durban, South Africa: "learning-by-doing" at the local government coal face. Environment and Urbanization 24: 167–95.

Saito-Jensen, M., & Pasgaard, M. (2014). Blocked learning in development aid? Reporting success rather than failure in Andhra Pradesh, India. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 10, 4–20.

Saito-Jensen, M., Rutt, R. L., & Chhetri, B. B. K. (2014). Social and environmental tensions: Affirmative measures under REDD plus carbon payment initiatives in Nepal. Human Ecology, 42, 683–694.

Sallu, S. M., C. Twyman, and L. C. Stringer (2010). Resilient or vulnerable livelihoods? Assessing livelihood dynamics and trajectories in rural botswana. Ecology and Society 15.

Sarker, M. N. I., Cao, Q., Wu, M., Hossin, M. A., Alam, G. M. M., & Shouse, R. C. (2019). Vulnerability and livelihood resilience in the face of natural disaster: A critical conceptual review. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 17, 12769–12785.

Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable rural livelihoods. A framework for analysis. IDS working paper 72

Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36, 171–196.

Scoones, I. (2015). Sustainable Livelihoods and Rural Development. Fernwood Publishing / Practical Action Publishing.

Sharifi, Z., Nooripoor, M., & Azadi, H. (2019). Zoning the villages of central district of Dena county in terms of sustainability of livelihood capitals. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 21(5), 1091–1106.

Small, L.-A. (2007). The sustainable rural livelihoods approach: A critical review. Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne D’études Du Développement, 28, 27–38.

Turnhout, E., Neves, K., & de Lijster, E. (2014). ‘Measurementality’ in biodiversity governance: Knowledge, transparency, and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Environment and Planning A, 46(3), 581–597.

Zabala, A., & Sullivan, C. A. (2018). Multilevel assessment of a large-scale programme for poverty alleviation and wetland conservation: Lessons from South Africa. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 61, 493–514.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank each and every restoration worker, contractor and manager for participating in our survey and interviews. We extend special thanks to Ed Gevers, Ivan Claws and Sphamatiola Zwaye for invaluable help in facilitating our fieldwork, and to Zama, Jadir and Sibonelo for assisting with the data collection. This paper was written as part of the project ‘Socio-Economic Benefits of Ecological Infrastructure’ (grant no. DFC File No. 17-M07-KU, funded by the Danish International Development Agency). We would like to thank our South African colleagues in SEBEI for introducing us to stakeholders and support us in the preparation for the field work undertaken. In particular, we would like to thank Nadine Methner, Stephanie Midgley, Alanna Rebelo, Petra Holden and Shaeden Gokool.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Aarhus Universitet.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pasgaard, M., Fold, N. How to Assess Livelihoods? Critical Reflections on the Use of Common Indicators to Capture Socioeconomic Outcomes for Ecological Restoration workers in South Africa. Soc Indic Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03433-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03433-5