Abstract

Migration presents challenges to receiving communities, as it tests their ability to respond to unexpected expenditures and social stresses. Evaluating the local impact of rapid and substantial migration flows is difficult due to the absence of a validated instrument for assessing community support for migration. Our study adapted and validated a Support for Migration Assessment survey (SMA) based on Social Exchange Theory (SET). The validation of the SMA contributes in two significant ways. First, it establishes an instrument that enables the assessment of support for migration (SFM) by considering community-level factors: trust in institutions (TII), overall community satisfaction (OCS), and perceived negative impact on infrastructure (INF). Second, the SMA extends SET to the context of migration to assess support by a receiving community. We recruited 333 survey participants between January and July 2022 using proportional stratified random sampling to measure locals’ perceptions toward the Venezuelan migrant population in Barranquilla, Colombia. The internal consistency of the factors was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha (α) and omega coefficient (ω), resulting in α = 0.88, ω = 0.89 for TII; α = 0.90, ω = 0.92 for OCS; α = 0.87, ω = 0.88 for INF; and α = 0.84, ω = 0.86 for SFM. After conducting exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, construct validity was confirmed based on the model’s goodness of fit (CFI = 0.939, TLI = 0.935, RMSEA = 0.062, SRMR = 0.076). The adapted survey demonstrates adequacy in assessing perceived community support for migration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As the number of forced migrants globally continues to climb with recent conflicts and climate disasters, it is important to consider that all of those displaced people must go somewhere. Significant population increase due to migration puts additional pressure on host communities’ infrastructure (Caron et al., 2022), especially in areas that lack existing resources to meet migrants’ physical, medical, and social needs (Chambers, 1986). The value of considering migrant host community support is underscored in the Global Compact on Refugees (United Nations, 2019), a United Nations-led international document providing guidelines on refugee response. The framework for refugee response developed in the Compact emphasizes the need and proposes processes to strengthen and support host countries and host communities. The Compact establishes indicators to measure progress towards better refugee response but focuses on top-level measurements such as number of donors and use of international humanitarian aid. Understanding how host community members themselves respond, and adapt to rapid in-migration, is also critical to developing insight about how best to support these communities during humanitarian events. This understanding may play a role in minimizing animosity towards the migrant/refugee population.

Building on empirical advances from the field of Tourism and Hospitality studies, we developed a survey to assess local host communities’ support for migration.Footnote 1 Both tourism and migration involve the shared use of resources that, with the massive arrival of people at a destination, may put pressure on the social and infrastructure systems of host communities. This pressure may affect the quality of life and satisfaction of residents by increasing the demand for public services and infrastructure and causing competition for resources. For instance, in the Canary Islands in Spain, the healthcare system has been under intense stress and roads have been overcrowded due to overtourism (Martiny, 2024). Recently, Venice implemented a $5 fee for tourists due to the excessive influx of visitors considering that the city’s narrow streets and infrastructure are not designed to accommodate such a large number of people (Bacon, 2024). In Japan, tourists crowd the narrow, picturesque streets of the area known as Gion, often following tour guides, making it difficult for locals to navigate and enjoy their own communities (Kageyama, 2024). These examples are consistent with what may be experienced in a migrant-receiving context. In general, the sudden increase in the number of people, whether tourists or migrants, can lead to road congestion, strains on social services, overcrowding of public shared spaces like parks, and overuse of common public goods, all of which can cause dissatisfaction among locals.

In this article, we rely on Social Exchange Theory (SET) to develop a unique survey for assessing host community support for migrants by considering community-level factors, derived from similar instruments used to measure tourism industry impacts on destination communities. The instrument was validated with survey data of residents in Barranquilla, Colombia in response to recent in-flows of Venezuelan migrants. Through extensive pilot testing and validation, we have adapted these instruments to characterize host communities’ response to support for migration. We find that the factors analyzed are reliable and valid, demonstrating that SET can be applied to migration studies. After providing a background of the context of Venezuelan migration to Colombia, we explain the adaptation, testing, and validation of a Support for Migration Assessment (SMA) survey based on social exchange theory (SET).

2 Background of Venezuelan Migration to Colombia

Migration from Venezuela has become a challenge for both migrants and receiving societies, predominantly in South America. Currently, Colombia stands out as the country with the highest number (approximately 2.9 million as of May 2024) of migrants and refugees from Venezuela, largely due to its geographical proximity (Fedesarrollo & Acrip, 2018; R4V, 2024). This rapid and large-scale migration raised several challenges in Colombia, including local integration, access to basic services, employment, and security (Bitar, 2022). In general, the local population’s abilities and willingness to support Venezuelan migrants have been tested.

The Colombian government established, and evolved, different protection and documentation strategies and mechanisms that, have allowed the regularization of migrants (Bedoya, 2020; Padilla et al., 2021). While several South American nations shut their borders, Colombia took an alternative approach, issuing special residence permits (PEPs) to Venezuelan migrants (Frydenlund et al., 2021). It allowed them to work and access health care between 2017 and 2020 (Real, 2022; Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, 2020). In 2018, the “Conpes” document was created. The purpose of the Conpes was to implement and strengthen care strategies for migrants and refugees in various areas, such as health, work, security, and housing (Rossiasco et al., 2023). In 2018, the government also established the Administrative Registry of Venezuelan Migrants in Colombia (RAMV), which collected information that served as a basis for formulating humanitarian assistance policy (Bedoya, 2020).

Despite government efforts to integrate Venezuelan migrants and address their needs, there are indications that social tensions have been increasing (Otis, 2020). According to a report prepared by Banco Mundial (2018), the large number of migrants who have moved from Venezuela to Colombia has generated pressures on institutions, infrastructure systems that provide services, the labor market, and the social dynamics. A survey by Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (2021) showed that the arrival of workers from Venezuela generates significant tension in the labor market, mainly in the informal sector. The Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID) study also revealed that, among Colombians, there is a perceived sense that neighborhoods and parks in areas of high concentrations of Venezuelans tend to also house criminal groups composed of Venezuelans, threatening locals’ perceived sense of safety and security. In addition, the survey from BID found that many Colombian citizens disagree with the policy measures taken by the government to integrate Venezuelan migrants. The BID findings affirm that locals are dissatisfied because they feel the government has not implemented enough migration controls.

3 Towards a Measure of Support for Migration

Unlike research on integration (Esses et al., 2017; Khasalamwa-Mwandha, 2021), our research focuses on the early years of forcibly displaced population movements, where local populations do not necessarily think of the migration as long-term or permanent. In that phase of humanitarian response, animosities towards migrants flare (Hangartner et al., 2019). Another field that studies the large and fast arrival of non-locals to a community, with an expectation of a short-term stay and that, in some instances, creates dissatisfaction in the local population, is tourismFootnote 2.

Santana-Gallego and Paniagua (2022) suggest that tourism can be considered a form of temporary migration that differs in terms of the duration of stay and underlying motivations. Both forms of population arrivals can create both challenges and opportunities for host communities. Both tourism and migration involve the transfer of resources between individuals with different characteristics, and although they can bring advantages, they can incur costs (Carrington et al., 2007; Witchayakawin et al., 2020).

Specifically for tourism, there are several benefits, such as generating new business opportunities, boosting employment, and increasing the host country’s monetary income (Lee & Chang, 2008; Paul Nkemngu, 2012). Additionally, tourism facilitates social and cultural exchange, promotes economic diversification, improves infrastructure, and motivates the preservation of natural resources to attract more visitors (Dwyer & Forsyth, 1993). On the other hand, tourism can result in increased expenditures for daily necessities (Kwan & Mccartney, 2005) and escalated property and housing prices (Ansar & Md. Khaled, 2021; Cong et al., 2023). Tourism also can give rise to additional issues, such as crime and the overuse of infrastructure (Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004; Recher & Rubil, 2020).

Migration, in the long-term beyond the initial humanitarian situation, can provide benefits to local communities. The influx of skilled migrant workers can help alleviate labor shortages in the local job market, resulting in economic benefits for the native population (Borjas, 1995; Carrington et al., 2007; Gutiérrez et al., 2020; Segal, 2019). Additionally, Aruj (2008) suggests that working-age migrants can contribute to financing social security programs for native residents in some countries. The presence of migrants can also lead to increased consumption and tax revenues for local governments (Gutiérrez et al., 2020). On the other hand, migration may impact host countries and communities by increasing labor market competition (Gutiérrez et al., 2020), degrading access to services particularly in resource-poor contexts (Burnham et al., 2003), and increasing xenophobic tensions (Rodicio-García & Gorgoso, 2019; Segal, 2019).

While migration is often assessed in the long-term, we need to make a short-term assessment, especially considering the social and infrastructure responses a community provides. This is where studies in tourism facilitate that assessment; by characterizing the community instead of characterizing the migrant. By characterizing migrants we mean, explaining the attitudes of the local population in relation to migrants’ attributes such as their job skills, language difference, race, place of origin, and religion, among others (Bansak et al., 2016; Hainmueller & Hangartner, 2013; Helbling & Kriesi, 2014; Hopkins, 2015). By characterizing the community, we mean explaining the attitudes of the local population in relation to their environment when sharing their space with migrants.

Extensive research has been done to develop survey instruments and models of destination communities’ support for tourism based on Social Exchange Theory (SET) (Alim et al., 2021; Gursoy & Kendall, 2006; Kim & Manoli, 2022; Kim & Park, 2023; Nunkoo, 2016; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2010; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2011; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2012; Nunkoo & So, 2016; Paraskevaidis & Andriotis, 2017; Perić, 2018; Ramkissoon & Nunkoo, 2011; Van Der Steen & Richards, 2021; Vinerean et al., 2021; Yao & Schwarz, 2018). While some researchers view SET through a predominantly economic and rational actor lens, SET can be interpreted more broadly as tangible or intangible exchange that may not necessarily be driven by rational thoughts or actions, but through “sentiment and habit” as well (Emerson, 1976, p. 341). These exchanges can be economic/monetary, but also include gift-giving and doing favors for others, where there are differing expectations of reciprocation that can unfold across different short-term and long-term timeframes and socio-cultural value systems (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). The underlying motivation for SET in tourism survey instruments is measuring locals’ perceptions of both monetary and non-monetary costs and benefits of receiving temporary populations. Previous SET survey instruments in the Tourism and Hospitality field has included measuring “emotional solidarity” with non-locals (Woosnam, 2011, 2012; Woosnam et al., 2009), perceived impact on community growth and recreational activities (Andereck et al., 2005; Lankford & Howard, 1994), feelings of empowerment that locals have a say in the management of their communities (Boley et al., 2014), state of the local economy (Gursoy et al., 2002), and perceptions of cultural disrespect or even threat (Vargas-Sánchez et al., 2011; Ward & Berno, 2011). The broad generalizability of these concepts to other local/non-local contexts motivated our study to evaluate the adaptability of these SET-based instruments to a migration context in which host communities were receiving non-locals in complex, often intangible exchange relationships. In the SET-based Tourism and Hospitality literature, we identified common factors such as trust in government institutions, perceived costs, and community satisfaction that could be extended to a migration context.

In the next section, we describe the factors considered when consolidating several Tourism and Hospitality instruments and adapting these to the migration context. Given some of the notable differences between voluntary tourism and forced displacement, some items were adapted to suit the specific migration context and interests of this study, showing that these are valid in the context of Venezuelan migration.

We relied on social science and Tourism and Hospitality literature to inform the adaptation and design of factors and questions related to key factors that correspond to Support for Migration (SFM) and three community-level factors: (1) Overall Community Satisfaction (OCS), (2) Negative (perceived) Impact on Infrastructure (INF), and (3) Trust in Institutions (TII). These factors were derived from SET and related theories used in Tourism and Hospitality Studies to understand the impact of non-locals into a destination community. The survey tool was tested in the case of Venezuelan migration into Colombia to assess locals’ perceptions of their communities regarding the situation.

3.1 Support for Migration

The factor of support is the central theme in quantitative studies on tourism and, in the case of our study, on migration. We define it as the community’s willingness to live with and support migrants. Literature on tourism has explored how the perceived state of the economy impacts support for tourism, where improved economic standing increases support (Gursoy et al., 2002). One study even found that concern about the economy trumped other potential social or cultural benefits derived from tourism (Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004). Others confirm these linkages between perceived state of the country of community as well as adding that crime, crowding, and traffic (Andereck et al., 2005; Ap & Crompton, 1998) play important roles in declining support for tourism. By contrast, increased investment in community shared resources such as parks, better quality of life, and better selection of local merchants were found to increase support for tourism (Byrd et al., 2009). For the support for migration factor, our survey included questions about the locals’ willingness to live with migrants in their community, their willingness to support employment opportunities for migrants, and their willingness to provide financial assistance.

3.2 Community-Level Factors

3.2.1 Overall Community Satisfaction

Overall Community Satisfaction (OCS) underlies modern tourism literature which seems to have at its core the assumption that to maintain “sustainable” tourism (which in this case means that it can be managed over the long term, not ecotourism as one might think) one must manage the expectations and experiences of the host community in terms of roads, parks, and other tangible investments so that (in return) host community support tourism (or in our case, migration) in their city/region (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2011, 2012). Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (2010) found that residents who were satisfied with their community were more likely to perceive tourism as having positive impacts. The 19 questions for Overall Community Satisfaction factor (see Table 1) were derived from Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (2011) and tailored to the migration context of our research. Our questions explore community experiences and expectations related to satisfaction with the neighborhood, city, transportation, and infrastructure (see appendix 1). This makes them substantially different than Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (2011), who only propose four questions in their model. Additionally, we address experiences and expectations concerning safety, by considering additional evidence that insecurity can affect community satisfaction in Colombia (Romero, 2014).

3.2.2 Negative (Perceived) Impact on Infrastructure

Perceived impact on infrastructure is defined in this study as a community member’s perception of the impact of migration on local infrastructure such as housing, utilities, food, and health services. This factor was also adapted from Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (2011) who argue that higher perceptions of negative impacts lead to lower support in tourism (Gursoy et al., 2002, 2010; Gursoy & Rutherford, 2004; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2010). Our qualitative research in Colombia and other migrant-receiving host communities supports the notion that impacts to infrastructure, whether real or perceived, can affect locals’ support for migration. In Colombia, impacts to the operation and budgets of hospitals caused by Venezuelan migrants seeking emergency medical services after crossing the border dominated the news cycles in recent years, both nationally and globally. Similarly, in other migrant-receiving host communities, the authors have recorded interviews with locals and noted that visibility in the form of lines at ATMs for banking, parks with migrants living in them, and full public buses fuels frustration by locals about migration management.

3.2.3 Trust in Institutions

From a tourism context, Gilson (2003) points out that trust is fundamental to forging relationships between a government and a community, which drives economic growth and fosters outcomes that benefit society as a whole. A lack of trust in public institutions can challenge the management of a government system (Hetherington, 1998) and can compromise the acceptance of tourism in a given area and generate judgments towards certain sectors (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2011). Research by Grzeskowiak et al. (2003) and Widgery (1982) revealed that inhabitants with a high level of trust expressed greater satisfaction with their community compared to those with a low level of trust. In our survey, we operationalized Trust in Institutions as a measure of local’s perception that the government and humanitarian aid agencies were responding appropriately to the migration phenomenon and that they felt their voices were heard in local and national politics. Research in other contexts has demonstrated the important role that government plays in the perception of support for migrants. For example, McLaren (2012) indicates that concerns about migration can undermine trust in political systems. Similarly, research from the European Social Survey (ESS) concludes that higher levels of political trust are associated with greater public support for various migrant groups and more generous refugee policy in Europe (Macdonald & Cornacchione, 2023).

4 Methods

4.1 Qualitative Validation and Transcultural Adaptation

Given that the literature and selected questions were originally in English, but our study was conducted in Colombia, an iterative transcultural adaptation process was crucial to adapt the survey to Spanish specifically in a Colombian migration context. The consent form and questions were translated from English to Spanish and thoroughly reviewed by the research team before receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB). A pilot test was conducted and involved gathering feedback from nine respondents with diverse backgrounds and educational levels in the first round, and input from experts in Sociology, Psychology, and Semiotics in the second round. Their input changed the structure and word choice of certain questions to ensure respondents would understand the question as the research team intended. The third version of the survey was tested with 20 Spanish-speaking participants to ensure clarity, format, and length. After confirming its clarity, the survey underwent a final review by the IRB in both the United States and Colombia.Footnote 3

Upon obtaining approval from the IRBs, the final instrument comprised seven sociodemographic questions and 45 items about the abovementioned factors (see Appendix 1), taking approximately 20 min on average to complete. The response options were provided on different Likert-type scales (see Table 2). The instrument was uploaded to the Survey Monkey platform for responses between January and July 2022.

4.2 Procedure and Ethical Considerations

The subjects were recruited through flyers distributed in various places in the city of Barranquilla, Colombia, and surrounding municipalities to have a balanced sample stratification across gender, age, and economic strata. The Colombian government uses the term stratum (strata, plural) to categorize neighborhoods by overall housing conditions (often related to income level), playing a role in taxation and social aid (1 for those with the lowest income and 6 for those with the highest income). All data collection sites were public, so a letter of authorization from any specific entity was not required to conduct the study. In addition, the research team also advertised the survey via social media platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram.

Only Colombian citizens were recruited to participate in the survey, as the objective was to assess the local response and perspective. Lastly, participants did not receive any compensation or economic benefit, and their participation was completely voluntary.

4.3 Participants

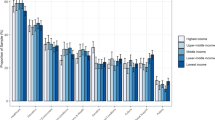

Data was collected using a proportional stratified random sampling method (Iliyasu & Etikan, 2021). This sampling approach ensures that individuals from different demographic groups (age, gender, and economic strata) were represented in the sample. After collecting and filtering the data, the responses of 333 participants, living in Barranquilla and surrounding areas of Colombia, were used. This number met the minimum requirement of 200 for confirmatory factor analysis (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Hair et al., 2014). Figure 1 presents the distribution of the sample by economic stratum, gender, and age. Additionally, a power test was carried out for the sample size collected to have a double validation of a suitable sample size to detect significant effects. The results showed good sample power by meeting a value above 80% (Cumming, 2013; Ellis, 2010).

The criteria for participation required that participants be over 18 years old, not part of a vulnerable population (people with cognitive disabilities, for instance), were Colombian citizens, and had lived 5 years or more in the place of residence. It was done to ensure that responses correspond to people who had experienced, or observed, the migration situation unfold.

4.4 Support for Migration Assessment (SMA) Survey

The survey items were organized into the four factors outlined in Table 1. Overall Community Satisfaction was composed of 19 items, Support for Migration of 6 items, Perceived Negative Impact on Infrastructure of 11 items, and Trust in Institutions of 9 items. Table 1 shows the distribution of items by factor. The survey questions comprised several Likert scales, as shown in Table 2. Appendix 1 provides the complete list of the Support for Migration Assessment (SMA) items’ descriptions.

4.5 Data Analysis

Participants were allowed to respond “I don’t know” if they were unsure or did not want to express their opinion on some questions related to the impact on infrastructure and trust in institutions. These responses were treated as missing values, and to avoid a significant decrease in the sample size, the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) method was used to impute them. The KNN method was selected because it is efficient and reliable for estimating missing values even in Likert-type response scales (Jadhav et al., 2019; Jonsson & Wohlin, 2004).

We used exploratory factor analysis to determine the structure and reliability index. To validate the factorial structure, we used confirmatory factor analysis. The validity of the measurement model was assessed through goodness-of-fit and discriminant validity analysis of the factors. These analyses are described in more detail below.

5 Limitations

This research has some limitations that should be addressed in future studies. First, the research focuses exclusively on the city of Barranquilla, which means that caution should be considered in not generalizing the findings to the Colombian population. The socioeconomic, cultural, and demographic characteristics of Barranquilla may differ from those of other regions of the country. In addition, it is not known at this time how these results would hold up in other South American contexts or in situations of global migration, but it is worth exploring. As we continue to work to apply this research in other migration contexts, we encourage the broader scientific community to consider these aspects to provide a more complete, generalizable, and comparable understanding of the migration phenomenon.

6 Results

6.1 Exploratory Factor Analysis

Initially, polychoric correlations between items within each factor were examined to facilitate the application of the factor analysis technique. This type of correlation matrix was employed due to the ordinal nature of the Likert-type scales used to measure the factors (Holgado–Tello et al., 2010). As a result, items 33, 34, 35, and 36, which were part of the factor Perceived Negative Impact on Infrastructure, and item 37, which belonged to the factor Trust in Institutions, were excluded because they presented low multicollinearity, defined as less than 0.3 (Ricardo-Barreto et al., 2020).

Subsequently, the critical assumptions for factor analysis were evaluated, including Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser Meyer Olkin test (KMO). It was concluded that, for all factors, the correlation matrix differed from the identity matrix and that there was a sufficient correlation between items within each factor to perform the factor analysis (Romero & Mora, 2020). Test statistics of assumptions for each factor are provided in Table 3.

After assessing the basic assumptions, we checked whether the factors were one-dimensional or not (based on the appropriate number of sub-factors to be retained). Subsequently, the principal axis method was used to extract the factor structure. This method was used because it was considered robust to the systematic non-compliance of multivariate normality when working with ordinal scales such as the Likert-type scale (Mavrou, 2015; Oliden & Zumbo, 2008). In addition, varimax rotation was employed, which emphasizes the factor weights to ensure that each item is represented in a single factor, reducing their totality (Martínez & Sepúlveda, 2012).

Support for Migration, Negative Impact on Infrastructure, and Trust in Institutions maintained one-dimensionality, so each was constituted with a first-order factor structure. In other words, all the items belonging to each factor measure the same aspect. On the other hand, Overall Community Satisfaction comprised a second-order factor structure formed by three first-order latent subfactors. These sub-factors were named according to the social context: (1) Community Expectations, (2) Safety and Transportation Satisfaction, and (3) Infrastructure Satisfaction. Item 9 regarding the satisfaction about health services had the same factor loadings on sub-factors 2 and 3, so it was placed only to load on 3 due to the nature of the question and its relationship to the sub-factor.

Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha index (α), an indicator that assesses the degree of correlation among items that are part of the same scale, using polychoric correlation matrices (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Some scholars warn that using Cronbach’s alpha index should be used carefully, considering the assumptions of normality, correlated errors, and equal factor loadings on all items (tau equivalence) (Cortina, 1993; Ventura-León & Caycho-Rodríguez, 2017; Yang & Green, 2011). To compensate for potential issues with Cronbach’s alpha index, we also used the omega coefficient (ω) developed by McDonald (1999) to evaluate internal consistency.

The findings indicated that all the factors of the instrument exhibit sufficient internal consistency with values of α and ω above 0.7 (Campo-Arias & Oviedo, 2008; Oviedo & Campo-Arias, 2005). Therefore, survey items consistently measure the intended factors. Factor loadings and internal consistency indicators for each factor are presented in detail below (see tables 4, 5, 6, 7).

6.2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Based on the exploratory factor analysis results, two measurement models were specified and assessed using confirmatory factor analysis. Measurement Model 1 tested the one-dimensionality of all factors, while measurement Model 2 tested community satisfaction as a multidimensional factor. The diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimation method was used. This method offers more accurate estimates of the model parameters by considering the ordinal nature of the factors and the non-compliance with multivariate normality (Mindrila, 2010). The chi-square statistic (x2) was used to test the goodness-of-fit of the measurement models. However, to avoid depending on its sensitivity to sample size (Santabárbara & López-Antón, 2019), a battery of performance indices was chosen to complement the results. The above included the chi-square ratio over degrees of freedom (x2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). These indicators are less affected than others by sample size and model complexity (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Taasoobshirazi & Wang, 2016; Trejos-Herrera et al., 2018). A model shows a good fit to the data when a value lower than three is obtained for x2/df (Santabárbara & López-Antón, 2019), values above 0.9 for the CFI and TLI indicators and below 0.08 for the RMSEA and SRMR (Morata-Ramírez et al., 2015; Yucel et al., 2020).

The findings indicate that the measurement Model 2 (Fig. 2) better fits the data (meets required thresholds) compared to measurement Model 1 (Table 8). Notably, Model 1 does not meet the required threshold for SRMR.

Measurement Model 2 (three first-order and one second-order factor). Note. Standardized factor loadings and covariances are shown; OCS = Overall Community Satisfaction; IS = Infrastructure Satisfaction; CE = Community Expectations; SR = Safety and Transportation Satisfaction; SFM = Support for Migration; INF = Perceived Negative Impact on Infrastructure; TII = Trust in Institutions

6.3 Validity Indicators

The concepts of convergent and discriminant validity were used to assess construct validity, as suggested by Santabárbara and López-Antón (2019). The convergent validity of a measurement model refers to the degree of certainty that a set of proposed items measure the same factor (Rubia, 2019). For this, the average variance extracted (AVE) of the factor is found and must be greater than or equal to 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). A satisfactory result indicates that the items explain 50% or more of the variability of the factor. On the other hand, discriminant or divergent validity determines whether the latent factors, which theoretically should not be related, are not (Hubley, 2014); i.e., each construct measures a different concept. This type of validity is fulfilled if the square root of the mean variance extracted from each factor is greater than the shared variance between pairs of factors (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Table 9 provides evidence that measurement model 2 not only fits the data well but also demonstrates convergent and discriminant validity among the factors examined. This finding indicates that the model robustly represents the underlying constructs.

7 Discussion

We found that the SET-based survey questions derived from validated instruments from Tourism and Hospitality studies can effectively and reliably be adapted to a migration context, specifically in our case of Venezuelan migration to Barranquilla, Colombia. We call this survey the Support for Migration Assessment (SMA).

Model 2 (Fig. 2) was determined to be the best fit for our survey data. We found that Support for Migration, Negative Impact on Infrastructure, and Trust in Institutions are valid first-order factors with good internal consistency. These results are consistent with the existing literature from Social Exchange Theory and Tourism and Hospitality studies and highlight their importance in the analysis of the perceived impact of forced migration on host communities. Overall Community Satisfaction had a second-order factor structure, consistent with previous tourism research (Filkins et al., 2000; Grzeskowiak et al., 2003; Sirgy & Cornwell, 2001; Sirgy et al., 2000). The finding suggests that, in the context of migration, community satisfaction is a multidimensional construct comprising different aspects, such as community expectations, safety and transportation, and satisfaction with infrastructure. By separately assessing these dimensions, we gain a comprehensive understanding of resident satisfaction, which is essential for informed decision-making and effective community development strategies.

That is not to say that these are the only factors contributing to Overall Community Satisfaction, so they are not intended to be direct policy recommendations. The tests in this study suggest that understanding of these second-order factors can reliably help us to understand Overall Community Satisfaction. The importance of Safety and Transportation in the model is not likely a complete representation of the only elements that influence Overall Community Satisfaction. Integrated Threat Theory, developed on the phenomenon of migrant integration (Stephan & Stephan, 2013) but also used in SET-based tourism research (Ward & Berno, 2011), suggests that both physical and symbolic socio-cultural threats to the host community can shape perceptions of migrants. The survey items referring to safety and transportation may reflect some aspects of physical threats sensed by locals with regards to physically navigating their normal community spaces. This second-order construct could be explored in more depth through future interviews with local host communities to uncover additional factors that contribute to spatial Overall Community Satisfaction. Likewise, the representation of infrastructure in the survey items could be improved to be more comprehensive. The current survey, however, was intended to be comprehensive and yet short enough to avoid respondent fatigue, so these additions would likely need to be parsimonious.

It is important to note here that the model does not establish causal relationships between the four factors (this will be studied in subsequent research). Rather, the confirmatory factor analysis found statistically significant covariance between the factors, which indicates that there is a non-random relationship between them. That is, when one factor changes, the other also tends to change in a predictable direction. This could hint at possible relationships that are congruent with other forms of research and are worth exploring in future studies.

Our research revealed a positive and significant covariance between Trust in Institutions, Community Satisfaction, and Support for Migration. We also found a negative and significant covariance between Trust in Institutions and perceived Negative Impact on Infrastructure. These findings underscore the interrelation of the factors, suggesting that if one factor improves, the others are likely to improve as well. For example, if trust in institutions increases, we may see a rise in community satisfaction and support for migration. However, as mentioned above, these are just initial indications of the factors’ relationships. It is crucial to delve into their causal relationships in future studies as this could significantly impact our understanding of these dynamics.

The SMA survey is a starting point for further analyses that could include latent class analysis, invariance analysis, and structural equation modeling to provide a data-driven decision-support tool for supporting migrant-receiving host communities so that they can continue to welcome migrants for the duration of humanitarian events.

8 Conclusion

Social exchange theory (SET) is based on the premise that human interactions are governed by a (tangible or intangible) cost-benefit analysis, which is particularly relevant when we are investigating shared resources such as infrastructure, public services, and labor opportunities among migrants and host communities. While Tourism and Hospitality studies have made significant headway in using SET to develop instruments to measure community support for tourism and tourism development, the potential for extending these insights to other contexts such as migrant-receiving communities has been largely unexplored.

This research adapted and validated a survey based on SET-based instruments from Tourism and Hospitality studies to measure four factors that allow to assess community’s support for migration. One of this study’s most significant theoretical contributions lies in extending the SET theoretical framework to the migration context, demonstrating that the factors that drive community support in the tourism context are also relevant in the migration context. These findings highlight the multifaceted nature of the drivers of host community support, which would be worth exploring beyond tourism and migration.

Overall, the study provides a valuable starting place for researchers and practitioners interested in understanding host community dynamics in a migration context. We established empirical evidence that the adapted migration survey is valid and internally reliable, which was tested with a Spanish language survey conducted in Barranquilla, Colombia on host communities’ perceptions of the Venezuelan migration situation. Future studies should further explore the causal relationships between factors as well as the extensibility of this survey to other migration contexts and other host community languages. Deeper insights derived from larger and more diverse samples across different migration host community contexts could provide humanitarian response decision-makers with insights about how to prioritize aid to migrants and host communities and identify indicators that local support for migration is declining. This information could help to prevent xenophobic sentiments and even actions towards refugees and migrants.

9 Appendix 1

Items of the Support for Migration Assessment Survey.

Spanish Version.

No. | Preguntas sociodemográficas |

|---|---|

1 | ¿En qué categoría se encuentra su edad? |

2 | Sexo/Identidad de género |

3 | ¿En qué ciudad vive actualmente? |

4 | ¿Ha vivido en esta ciudad por lo menos desde el 2017? |

5 | ¿Cuál es su nacionalidad? |

6 | ¿Cuál es el nivel educativo más alto que ha logrado? |

7 | ¿A cuál estrato socioeconómico pertenece? |

No. | Items |

1 | Su barrio es un lugar deseable para vivir |

2 | Su ciudad es un lugar deseable para vivir |

3 | Cuando piensa en el futuro de su vida aquí en su barrio se siente |

4 | Cuando piensa en el futuro de su vida aquí en su ciudad se siente |

5 | En los últimos 5 años, las condiciones de seguridad en su ciudad han sido |

6 | En los últimos 5 años, las condiciones de movilidad vial en su ciudad han sido |

7 | En los últimos 5 años, las condiciones de servicios públicos en su ciudad han sido |

8 | En los últimos 5 años, las condiciones de acceso a vivienda en su ciudad han sido |

9 | En los últimos 5 años, las condiciones de servicios de salud en su ciudad han sido |

10 | En los últimos 5 años, las condiciones de empleo en su ciudad han sido |

11 | En los últimos 5 años, las condiciones de recreación y deporte de recreación en su ciudad han sido |

12 | Las condiciones futuras de seguridad en su ciudad serán mejores que las actuales |

13 | Las condiciones futuras de movilidad vial en su ciudad serán mejores que las actuales |

14 | Las condiciones futuras de servicios públicos en su ciudad serán mejores que las actuales |

15 | Las condiciones futuras de acceso a vivienda en su ciudad serán mejores que las actuales |

16 | Las condiciones futuras de servicios de salud en su ciudad serán mejores que las actuales |

17 | Las condiciones futuras de empleo en su ciudad serán mejores que las actuales |

18 | Las condiciones futuras de recreación y deporte en su ciudad serán mejores que las actuales |

19 | La satisfacción general que siente sobre su calidad de vida ha mejorado en los últimos 5 años |

20 | Apoya la posibilidad de que los migrantes venezolanos vivan en su barrio |

21 | Apoya la posibilidad de que los migrantes venezolanos vivan en su ciudad |

22 | Apoya que los migrantes venezolanos trabajen en su ciudad: |

23 | Apoya que se les preste ayuda financiera a los migrantes venezolanos en su ciudad |

24 | ¿Cómo le ha afectado a usted, a su familia o a sus amigos la presencia de migrantes venezolanos en su ciudad? |

25 | Los migrantes venezolanos pueden permanecer en su ciudad durante |

26 | La presencia de migrantes venezolanos ha afectado negativamente el manejo de residuos sólidos en su ciudad |

27 | La presencia de migrantes venezolanos ha afectado negativamente el agua en su ciudad |

28 | La presencia de migrantes venezolanos ha afectado negativamente el acceso a parques en su ciudad |

29 | La presencia de migrantes venezolanos ha afectado negativamente la disponibilidad de alimentos en su ciudad |

30 | La presencia de migrantes venezolanos ha afectado negativamente el precio de los alimentos en su ciudad |

31 | La presencia de migrantes venezolanos ha afectado negativamente la atención de urgencias en salud en su ciudad |

32 | La presencia de migrantes venezolanos ha afectado negativamente la atención preventiva en salud en su ciudad |

33 | ¿Por cuánto tiempo cree que los migrantes venezolanos se quedarán en su ciudad? |

34 | ¿Ha sido testigo de cómo los migrantes venezolanos han sido objeto de acoso o ataques? |

35 | ¿Ha sido testigo de cómo los migrantes venezolanos acosan o atacan a los ciudadanos locales? |

36 | Los migrantes venezolanos han modificado los precios de los productos y servicios haciéndolos |

37 | Se siente informado sobre los temas de migración en su ciudad. |

38 | La respuesta del gobierno local ante la realidad de la migración venezolana en su ciudad ha sido |

39 | Con el pasar del tiempo, la respuesta del gobierno local en su ciudad ante la realidad de la migración venezolana ha |

40 | El gobierno local se preocupa por usted y por su ciudad |

41 | La respuesta del gobierno nacional ante la realidad de la migración venezolana en su ciudad ha sido |

42 | Con el pasar del tiempo, la respuesta del gobierno nacional ante la realidad de la migración venezolana ha |

43 | ¿Confía en el gobierno nacional para gestionar los asuntos relacionados con la migración? |

44 | La respuesta de las Organizaciones No Gubernamentales (ONG), fundaciones, organizaciones religiosas o de caridad ante la realidad de la migración venezolana en su ciudad ha sido |

45 | Con el pasar del tiempo, la respuesta las Organizaciones no Gubernamentales (ONG), fundaciones, organizaciones religiosas o de caridad ha sido |

English Version.

No. | Sociodemographic Questions |

|---|---|

1 | Which category includes your age? |

2 | Sex/Gender Identity |

3 | What city do you currently live in? |

4 | Have you lived in this city since 2017? |

5 | What is your nationality? |

6 | What is the highest level of education you have completed? |

7 | Which socioeconomic stratum do you belong to? |

No. | Items |

1 | My town is a desirable place to live. |

2 | My city is a desirable place to live. |

3 | When I think about my future life here in my town, I feel. |

4 | When I think about my future life here in my city, I feel. |

5 | In the last 5 years, the following conditions in my city have been (security) |

6 | In the last 5 years, the following conditions in my city have been (transportation). |

7 | In the last 5 years, the following conditions in my city have been (utilities). |

8 | In the last 5 years, the following conditions in my city have been (access to housing). |

9 | In the last 5 years, the following conditions in my city have been (health services). |

10 | In the last 5 years, the following conditions in my city have been (employment). |

11 | In the last 5 years, the following conditions in my city have been (recreation and sports facilities). |

12 | Future conditions of the following aspects in my community will be better than the current ones (security). |

13 | Future conditions of the following aspects in my community will be better than the current ones (Transportation). |

14 | Future conditions of the following aspects in my community will be better than the current ones (utilities). |

15 | Future conditions of the following aspects in my community will be better than the current ones (access to housing). |

16 | Future conditions of the following aspects in my community will be better than the current ones (health services). |

17 | Future conditions of the following aspects in my community will be better than the current ones (employment). |

18 | Future conditions of the following aspects in my community will be better than the current ones (recreation and sports facilities). |

19 | The overall satisfaction I feel about my quality of life has improved. |

20 | I support the possibility that Venezuelan migrants live in my town. |

21 | I support the possibility that Venezuelan migrants live in my city. |

22 | I support Venezuelan migrants working in my city. |

23 | Do you support financial aid to the Venezuelan migrants in your city? |

24 | How has the presence of Venezuelan migrants in my city affected me, my family, and my friends? |

25 | Venezuelan migrants can stay in my city for: |

26 | Venezuelan migrants’ presence has affected these services (solid waste management). |

27 | Venezuelan migrants’ presence has affected these services (water). |

28 | Venezuelan migrants’ presence has affected these services (access to parks). |

29 | Venezuelan migrants’ presence has affected these services (food availability). |

30 | Venezuelan migrants’ presence has affected these services (food prices). |

31 | Venezuelan migrants’ presence has affected these services (emergency health care). |

32 | Venezuelan migrants’ presence has affected these services (Preventive care services in health). |

33 | For how long I think the Venezuelan migrants will stay in my city |

34 | Have you witnessed how the Venezuelan migrants have been object of harassment or attacks? |

35 | Have you witnessed how the Venezuelan migrants harass or attack the local citizens? |

36 | Venezuelan migrants have modified price products and services by making them: |

37 | You feel that you are well informed about migration issues |

38 | The local government’s response to Venezuelan migration in your city has been. |

39 | With the passing of time, the local government’s response in your city to Venezuelan migration has. |

40 | The local government cares about you and your city. |

41 | The national government’s response to Venezuelan migration’s reality in your city has been. |

42 | With the passing of time, the national government’s response to Venezuelan migration has. |

43 | The non-governmental organizations (ONG) response, religious organizations, or charitable organizations’ response to Venezuelan migration in your city has been. |

44 | With the passing of time, the non-governmental organizations (ONG), religious organizations, or charitable organizations’ response has. |

45 | Do you trust the national government to manage migration-related issues? |

Notes

Throughout this study, we use the word “migrant” and “migration” to broadly describe the phenomena of people moving, with some presumptions of temporariness, into a city or region that is not their own. We are speaking specifically about refugees and other forcibly displaced persons in this context, but use the word “migrant” to avoid conflating the unexpected movement of people with complex migration pathways and bureaucratic processes (to include those who do not have access to refugee status or asylum claims) and borders (to include those who do not flee across international borders but are nonetheless displaced).

Of course, we must recognize that tourism is highly voluntary and can generate significant revenues for destination locations; by contrast, displacement is largely unplanned, and destination (or intermediate transit) locations may be entirely unprepared to receive a large influx of people. We do not want to minimize these significant differences. Our research seeks to build from and adapt the existing validated measures that Tourism and Hospitality Studies have contributed to understanding the impacts of temporary population surges on local communities as a starting point to understand how local communities respond to sudden, large humanitarian movements of populations.

This research was categorized as “minimal risk research” based on the principles outlined in Resolution 8430 of 1993 by the Colombian Ministry of Health Ministerio de Salud. (1993). Resolución # 008430 de 1993 por la cual se establecen las normas científicas, técnicas y administrativas para la investigación en salud. República de Colombia. Retrieved from https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/DIJ/RESOLUCION-8430-DE-1993.PDF.

References

Alim, M. A., Jee, T. W., Voon, M. L., Ngui, K. S., & Kasuma, J. (2021). Tourism Development through communities’ support: Rural communities’ perspective. Geo Journal of Tourism and Geosites, 39, 1473–1482.

Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1056–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.03.001.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Ansar, A., & Md. Khaled, A. F. (2021). From solidarity to resistance: Host communities’ evolving response to the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 6(1), 16.

Ap, J., & Crompton, J. L. (1998). Developing and testing a tourism impact scale. Journal of Travel Research, 37(2), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759803700203.

Aruj, R. S. (2008). Causas, consecuencias, efectos e impacto de las migraciones en Latinoamérica. Papeles De población, 14(55), 95–116.

Bacon, A. (2024). Venice’s plan to charge tourists descended into chaos, showing how much of a headache overtourism has become. Bussiness Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/venice-italy-plan-charge-tourists-turned-chaos-2024-4.

Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (2021). Las dos caras de la integración: Percepciones de colombianos y venezolanos sobre el fenómeno migratorio en Bogotá, Colombia. https://publications.iadb.org/es/las-dos-caras-de-la-integracion-percepciones-de-colombianos-y-venezolanos-sobre-el-fenomeno.

Banco Mundial (2018). Migración desde Venezuela a Colombia: impactos y estrategia de respuesta en el corto y mediano plazo. https://goo.gl/jCFv5R.

Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2016). How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers. Science, 354(6309), 217–222.

Bedoya, M. R. B. (2020). Migración venezolana hacia Colombia respuestas del estado (2015–2019). Revista Internacional De Cooperación Y Desarrollo, 7(2), 9–28.

Bitar, S. (2022). Migration in Colombia and public policy responses. Public Policy Paper Series (34). UNDP Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-11/PNUDLAC-working-paper-34-Colombia-ES. pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

Boley, B. B., McGehee, N. G., Perdue, R. R., & Long, P. (2014). Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a weberian lens. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.005.

Borjas, G. J. (1995). The economic benefits from immigration. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2), 3–22.

Burnham, G. M., Rowley, E. A., & Ovberedjo, M. O. (2003). Quality design: A planning methodology for the integration of refugee and local health services, West Nile. Uganda Disasters, 27(1), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00219.

Byrd, E. T., Bosley, H. E., & Dronberger, M. G. (2009). Comparisons of stakeholder perceptions of tourism impacts in rural eastern North Carolina. Tourism Management, 30(5), 693–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.10.021.

Campo-Arias, A., & Oviedo, H. C. (2008). Propiedades psicométricas de una escala: La consistencia interna. Revista De Salud pública, 10, 831–839.

Caron, R. M., Amorim Adegboye, R., Moreno-Leguizamon, A., Serre-Delcor, C. J., N., & Sherlaw, W. (2022). The impact of migration and resettlement on health. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 904697.

Carrington, K., McIntosh, A. F., & Walmsley, J. D. (2007). Introduction to’The social costs and benefits of Migration into Australia’. The social costs and benefits of Migration into Australia. University of New England.

Chambers, R. (1986). Hidden losers? The impact of rural refugees and refugee programs on poorer hosts. International Migration Review, 20(2), 245–263.

Cong, S., Chin, L., & Abdul Samad, A. R. (2023). Does urban tourism development impact urban housing prices? International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Cumming, G. (2013). Understanding the New Statistics: Effect Sizes, Confidence Intervals, and Meta-Analysis. Routledge.

Del Real, D. (2022). Seemingly inclusive liminal legality: The fragility and illegality production of Colombia’s legalization programmes for Venezuelan migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(15), 3580–3601.

Dwyer, L., & Forsyth, P. (1993). Assessing the benefits and costs of inbound tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 20(4), 751–768.

Ellis, P. D. (2010). The Essential Guide to Effect Sizes: Statistical Power, Meta-Analysis, and the Interpretation of Research Results. Cambridge University Press.

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social Exchange Theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2(1), 335–362. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003.

Esses, V. M., Hamilton, L. K., & Gaucher, D. (2017). The global refugee crisis: Empirical evidence and policy implications for improving public attitudes and facilitating refugee resettlement. Social Issues and Policy Review, 11(1), 78–123.

Fedesarrollo, & Acrip. (2018). &. Informe Mensual del Mercado Laboral: Migración Venezolana a Colombia. http://hdl.handle.net/11445/3688.

Filkins, R., Allen, J. C., & Cordes, S. (2000). Predicting community satisfaction among rural residents: An integrative model. Rural Sociology, 65(1), 72–86.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Frydenlund, E., Padilla, J. J., & Palacio, K. (2021). Colombia gives nearly 1 million Venezuelan migrants legal status and right to work. The Conversation, 3. https://theconversation.com/colombia-gives-nearly-1-million-venezuelan-migrants-legal-status-and-right-to-work-155448.

Gilson, L. (2003). Trust and the development of health care as a social institution. Social Science & Medicine, 56(7), 1453–1468.

Grzeskowiak, S., Sirgy, M. J., & Widgery, R. (2003). Residents’ satisfaction with community services: Predictors and outcomes. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 33(2).

Gursoy, D., & Kendall, K. (2006). Hosting mega events: Modeling locals’ support. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(3), 603–623.

Gursoy, D., & Rutherford, D. G. (2004). Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 495–516.

Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79–105.

Gursoy, D., Chi, C. G., & Dyer, P. (2010). Locals’ attitudes toward mass and alternative tourism: The case of Sunshine Coast, Australia. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 381–394.

Gutiérrez, J. M., Borré, J. R., Montero, R. A., & Mendoza, X. F. B. (2020). Migración: Contexto, impacto y desafío. Una reflexión teórica. Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 26(2), 299–313.

Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2013). Who gets a Swiss passport? A natural experiment in immigrant discrimination. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 159–187.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis (7 ed.). Pearson Education.

Hangartner, D., Dinas, E., Marbach, M., Matakos, K., & Xefteris, D. (2019). Does exposure to the refugee crisis make natives more hostile? American Political Science Review, 113(2), 442–455.

Helbling, M., & Kriesi, H. (2014). Why citizens prefer high-over low-skilled immigrants. Labor market competition, welfare state, and deservingness. European Sociological Review, 30(5), 595–614.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of political trust. American Political Science Review, 92(4), 791–808.

Holgado–Tello, F. P., Chacón–Moscoso, S., Barbero–García, I., & Vila–Abad, E. (2010). Polychoric versus Pearson correlations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables. Quality & Quantity, 44, 153–166.

Hopkins, D. J. (2015). The upside of accents: Language, inter-group difference, and attitudes toward immigration. British Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 531–557.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Hubley, A. (2014). Discriminant validity. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research, 1664–1667.

Iliyasu, R., & Etikan, I. (2021). Comparison of quota sampling and stratified random sampling. Biom Biostat Int J Rev, 10(1), 24–27.

Jadhav, A., Pramod, D., & Ramanathan, K. (2019). Comparison of performance of data imputation methods for numeric dataset. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 33(10), 913–933.

Jonsson, P., & Wohlin, C. (2004). An evaluation of k-nearest neighbour imputation using likert data. 10th International Symposium on Software Metrics, 2004. Proceedings.

Kageyama, Y. (2024). Kyoto’s picturesque geisha district fights back against over-tourism with keep-out signs. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/japan-tourism-kyoto-geisha-ban-1162257d8642a85db447a6f4afdbb249.

Khasalamwa-Mwandha, S. (2021). Local Integration as a durable solution? Negotiating socioeconomic spaces between refugees and Host Communities in Rural Northern Uganda. Sustainability, 13(19), 10831.

Kim, S., & Manoli, A. E. (2022). Does relationship quality matter in policy-making? The impact of government-public relationships and residents’ perceptions on their support towards a mega-sport event. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 14(2), 207–224.

Kim, S., & Park, E. (2023). An integrated model of social impacts and resident’s perceptions: From a film tourism destination. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(2), 395–421.

Kwan, A. V. C., & Mccartney, G. (2005). Mapping resident perceptions of gaming impact. Journal of Travel Research, 44(2), 177–187.

Lankford, S. V., & Howard, D. R. (1994). Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90008-6.

Lee, C. C., & Chang, C. P. (2008). Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tourism Management, 29(1), 180–192.

Macdonald, D., & Cornacchione, T. (2023). Political trust and support for immigration in the European mass public. Political Behavior, 45(2), 491–510.

Martínez, C. M., & Sepúlveda, M. A. R. (2012). Introducción Al análisis factorial exploratorio. Revista colombiana de psiquiatría, 41(1), 197–207.

Martiny, J. (2024). Spain: Canary Islands’ mass protests target overtourism. DW News. https://www.dw.com/en/spain-canary-islands-mass-protests-target-overtourism/a-68922697.

Mavrou, I. (2015). Análisis factorial exploratorio: Cuestiones conceptuales y metodológicas. Revista Nebrija De Lingüística Aplicada A La Enseñanza De Lenguas, 19, 71–80.

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. psychology.

McLaren, L. M. (2012). The cultural divide in Europe: Migration, multiculturalism, and political trust. World Politics, 64(2), 199–241.

Mindrila, D. (2010). Maximum likelihood (ML) and diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimation procedures: A comparison of estimation bias with ordinal and multivariate non-normal data. International Journal of Digital Society, 1(1), 60–66.

Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores (2020). Permiso especial de permanencia (PEP). Retrieved from https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/FOTOS2020/resolucion_cancilleria_nuevo_plazo_de_expedicion_pep_07092020.pdf.

Ministerio de Salud (1993). Resolución # 008430 de 1993 por la cual se establecen las normas científicas, técnicas y administrativas para la investigación en salud. República de Colombia. Retrieved from https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/DIJ/RESOLUCION-8430-DE-1993.PDF.

Morata-Ramírez, M., Holgado-Tello, F. P., Barbero-García, I., & Mendez, G. (2015). Análisis factorial confirmatorio: Recomendaciones sobre mínimos cuadrados no ponderados en función del error Tipo I De Ji-Cuadrado Y RMSEA. Acción psicológica, 12(1), 79–90.

Nunkoo, R. (2016). Toward a more comprehensive use of social exchange theory to study residents’ attitudes to tourism. Procedia Economics and Finance, 39, 588–596.

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2010). Modeling community support for a proposed integrated resort project. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(2), 257–277.

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011). Developing a community support model for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 964–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.01.017.

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2012). Structural equation modelling and regression analysis in tourism research. Current Issues in Tourism, 15(8), 777–802.

Nunkoo, R., & So, K. K. F. (2016). Residents’ support for tourism: Testing alternative structural models. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 847–861.

Oliden, P. E., & Zumbo, B. D. (2008). Coeficientes de fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada. Psicothema, 896–901.

Otis, J. (2020). Large venezuelan migration sparks xenophobic backlash in Colombia. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/12/29/949548865/large-venezuelan-migration-sparks-xenophobic-backlash-in-colombia.

Oviedo, H. C., & Campo-Arias, A. (2005). Aproximación Al uso del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Revista colombiana de psiquiatría, 34(4), 572–580.

Padilla, J., Frydenlund, E., & Palacio, K. (2021). Colombia is letting hundreds of thousands of venezuelans stay. What can other countries learn. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/03/11/columbia-is-letting-hundreds-thousands-venezuelans-stay-what-can-other-countries-learn/.

Paraskevaidis, P., & Andriotis, K. (2017). Altruism in tourism: Social exchange theory vs altruistic surplus phenomenon in host volunteering. Annals of Tourism Research, 62, 26–37.

Paul Nkemngu, A. (2012). Community benefit from tourism: Myth or reality a case study of the Soshanguve township. J Tourism Hospit, 1(105), 2167–02691000105.

Perić, M. (2018). Estimating the perceived socio-economic impacts of hosting large-scale sport tourism events. Social Sciences, 7(10), 176.

R4V (2024). Refugiados y migrantes de Venezuela. https://www.r4v.info/es/refugiadosymigrantes.

Ramkissoon, H., & Nunkoo, R. (2011). City image and perceived tourism impact: Evidence from Port Louis, Mauritius. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 12(2), 123–143.

Recher, V., & Rubil, I. (2020). More tourism, more crime: Evidence from Croatia. Social Indicators Research, 147, 651–675.

Ricardo-Barreto, C. T., Molinares, D. J., Llinás, H., Santodomíngo, J. M. P., Acevedo, C. M. A., Rodríguez, P. D. A., Navarro, C. P. B., & Villa, S. M. V. (2020). Trends in using ICT resources by professors in HEIs (higher education institutions). Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 19, 395–425.

Rodicio-García, M. L., & Gorgoso, M. C. S. (2019). Inserción Sociolaboral De mujeres emigrantes retornadas: Desde Venezuela a España. Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 25(4), 11–21.

Romero, D. (2014). Insecurity or perception of insecurity? Urban crime and dissatisfaction with life: Evidence from the case of Bogotá. Peace Economics Peace Science and Public Policy, 20(1), 169–208.

Romero, K. P., & Mora, O. M. (2020). Análisis factorial exploratorio mediante El uso de las medidas de adecuación muestral kmo y esfericidad de bartlett para determinar factores principales. Journal of Science and Research, 5(CININGEC), 903–924.

Rossiasco, P., de Narváez, P., Aguilera, A., Granados, G., Guerra, P., & Samad, T. (2023). Adapting public policies in response to an unprecedented influx of refugees and migrants: Colombia case study of migration from Venezuela. World development report.

Rubia, J. M. (2019). Review of the criteria for convergent validity estimated through the extracted average variance. Psychologia Avances De La Disciplina, 13(2), 25–41.

Santabárbara, J., & López-Antón, R. (2019). Validación preliminar de la escala de autoeficacia estadística en estudiantes de grado en Medicina españoles: análisis factorial confirmatorio. REIRE Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació, 12(2), 1–13.

Santana-Gallego, M., & Paniagua, J. (2022). Tourism and migration: Identifying the channels with gravity models. Tourism Economics, 28(2), 394–417.

Segal, U. (2019). Globalization, migration, and ethnicity. Public Health, 172, 135–142.

Sirgy, M. J., & Cornwell, T. (2001). Further validation of the Sirgy et al.‘s measure of community quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 56, 125–143.

Sirgy, M. J., Rahtz, D. R., Cicic, M., & Underwood, R. (2000). A method for assessing residents’ satisfaction with community-based services: A quality-of-life perspective. Social Indicators Research, 49, 279–316.

Stephan, W. S., & Stephan, C. W. (2013). An integrated threat theory of prejudice. Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 33–56). Psychology.

Taasoobshirazi, G., & Wang, S. (2016). The performance of the SRMR, RMSEA, CFI, and TLI: An examination of sample size, path size, and degrees of freedom. Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods, 11(3), 31–39.

Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International journal of medical education, 2, 53.

Trejos-Herrera, A. M., Bahamón, M. J., Alarcón-Vásquez, Y., Vélez, J. I., & Vinaccia, S. (2018). Validity and reliability of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Colombian adolescents. Psychosocial Intervention, 27(1), 56–63.

United Nations (2019). Global Compact on Refugees. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/5c658aed4.pdf.

Van Der Steen, T., & Richards, G. (2021). Factors affecting resident support for a hallmark cultural event: The 2018 European Capital of Culture in Valletta, Malta. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism Leisure and Events, 13(1), 107–123.

Vargas-Sánchez, A., Porras-Bueno,, N., & Plaza-Mejía, M. Á. (2011). Explaining residents’ attitudes to tourism: Is a universal model possible? Annals of Tourism Research, 38(2), 460–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.10.004.

Ventura-León, J. L., & Caycho-Rodríguez, T. (2017). El Coeficiente Omega: Un método alternativo para la estimación de la confiabilidad. Revista Latinoamericana De Ciencias Sociales niñez Y Juventud, 15(1), 625–627.

Vinerean, S., Opreana, A., Tileagă, C., & Popșa, R. E. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. Sustainability, 13(22), 12541.

Ward, C., & Berno, T. (2011). Beyond social exchange theory: Attitudes toward tourists. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1556–1569.

Widgery, R. N. (1982). Satisfaction with the quality of urban life: A predictive model. American Journal of Community Psychology, 10(1), 37.

Witchayakawin, P., Chantanupan, R., & Tabash, M. I. (2020). Impacts and benefits from tourism an example from Thailand. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 32(4), 1270–1276.

Woosnam, K. M. (2011). Testing a model of Durkheim’s theory of emotional solidarity among residents of a tourism community. Journal of Travel Research, 50(5), 546–558.

Woosnam, K. M. (2012). Using emotional solidarity to explain residents’ attitudes about tourism and tourism development. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 315–327.

Woosnam, K. M., Norman, W. C., & Ying, T. (2009). Exploring the theoretical framework of emotional solidarity between residents and tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 48(2), 245–258.

Yang, Y., & Green, S. B. (2011). Coefficient alpha: A reliability coefficient for the 21st century? Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(4), 377–392.

Yao, Q., & Schwarz, E. C. (2018). Impacts and implications of an annual major sport event: A host community perspective. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 161–169.

Yucel, S. C., Ergin, E., Orgun, F., Gokçen, M., & Eser, I. (2020). Estudio De validación Y confiabilidad del Moral Distress Questionnaire en idioma turco para enfermeros. Revista Latino-Americana De Enfermagem, 28, e3319.

Acknowledgements

Liss Romero & Lia Castillo (Universidad del Norte, Colombia) helped in the data collection process.

Funding

This research is funded by grant number N000141912624 by the Office of Naval Research through the Minerva Research Initiative; none of the views reported in the study are those of the funding organization.

Open Access funding provided by Colombia Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

The Old Dominion University Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the consent for the Computational Framework for Assessing Absorptive Capacity project with its respective materials and protocols for data collection in Colombia. The Spanish version of the informed consent form provided with the survey for Assessing Host Communities’ Support for Migration is presented below.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Botello, J.G., Palacio, K., Frydenlund, E. et al. Adapting and Validating a Survey to Assess Host Communities Support for Migration. Soc Indic Res 174, 697–720 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03397-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03397-6