Abstract

Exogenous events have the potential to affect citizens’ risk-perceptions, (in)security sentiments, electoral choices, policy preferences and institutional trust levels. It has been shown that migrant and refugee flows also affect citizens’ trust and policy preferences. The 2015 refugee crisis as it has come to be known, shook Europe’s cohesion and tested the existing immigration and asylum policies as well as acted as a further stimulus to populist/right wing Eurosceptic parties with an agenda of anti-immigrant restrictive policies. Expectedly, it has attracted considerable attention in the relevant literature. Building on existing studies that examine various aspects associated with the 2015 refugee crisis, the present paper examines its effect on institutional trust levels in Europe. Specifically, it focuses on trust towards the national government, the EU and the two state security services the police and the armed forces. To this effect, the study draws data from successive Eurobarometer surveys before and after the crisis. Employing segmented-type regression models as well as Oaxaca decomposition models it probes into the 2015 refugee crisis’ impact on the levels of institutional trust using over 400,000 responses to the relevant Eurobarometer questions. The results reported herein suggest the presence of “a rally around the flag effect”. Nonetheless, macroeconomic factors such as GDP growth and unemployment as well as differences in behavioural responses also explain a large part of the observed gap in trust before and after the 2015 refugee crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Institutional trust is trust in state’s institutions and organizations and includes trust towards international and intergovernmental organizations such as the UN or the EU (inter alia: Arpino & Obydenkova, 2020; Brosius et al., 2019; Harteveld et al., 2013; Hobolt & Wratil, 2015). As noted by Ervasti et al. (2019), trust in institutions is an essential component that contributes to the smooth functioning of a country and facilitates interactions between citizens and governmental institutions. The factors that influence and determine citizens’ levels of institutional trust have drawn considerable attention in the relevant literature (inter alia: Alesina & La Ferrara, 2002; Bjornskov, 2006; Keele, 2007; Newton & Zmerli, 2011; Uslaner, 2002). Although a thorough review of the extant literature on this theme is well beyond our scopes here, for our purposes it suffices to note that such institutional trust determinants include individuals’ demographic characteristics such as for instance age, gender, household type, educational level (inter alia: Kim et al., 2022; Uslaner, 2008). Similarly self-assessed well-being and the household’s economic situation, political self-placement across the left–right spectrum, ideological and political orientations, also have been cited as determinants that explain divergences in trust (inter alia: Bobzien, 2023; Tormos, 2019; Caïs et al., 2021).

Additionally, apart from the cohort of individual traits and characteristics, reported empirical evidence indicates that institutional trust is affected by exogenous events that affect citizens’ political behaviour, political attitudes and attitudes towards state institutions, electoral choices, value formation, risk-perceptions, (in)security sentiments, policy preferences and institutional trust (inter alia: Berrebi & Klor, 2008; Bozzoli and Müller, 2011; Arvanitidis et al., 2016; Hall & Werner, 2022; Bove & Di Leo, 2020). Such events include international crises, war and conflict, terrorist incidents, civil unrest and strife as well as the recent pandemic (inter alia: Helbling et al., 2023; Davvetas et al., 2022; Bækgaard et al., 2020; Economou & Kollias, 2019, 2023; Knudsen et al., 2023; Getmansky & Zeitzoff, 2014).

Both in Europe as well as in the United States migration and migration policies consistently rank high in the agenda of the political discourse (Mihalik & Bardovic, 2019). In 2015, European countries were confronted with an unprecedented surge in asylum applications by a record of 1.3 million mainly Syrian refugees and migrants from other countries of origin.Footnote 1 It has been shown that migrant and refugee flows affect citizens’ trust and policy preferences. For instance, as reported by Vasilakis (2018), the massive arrival of refugees in Greece had a positive and significant effect on voting behavior that favored extreme-right parties. Similarly, in the case of trust and attitudes towards the EU, findings indicate a strong and consistent association between opposition to inward irregular immigration and euroscepticism (inter alia: Scipioni et al., 2019; Vreese, 2017; Stockemer et al., 2018, 2020). Koos and Seiber (2019) report findings showing that on a country level factors such as a strong welfare state increases solidarity towards immigrants whereas on an individual level a precarious economic background and right-wing political orientation result in lower solidarity with immigrants and refugees.

The 2015 refugee crisis as it has come to be known, shook Europe’s cohesion and tested the existing immigration and asylum policies. It also acted as a further stimulus to populist/right wing Eurosceptic parties with an agenda of anti-immigrant restrictive policies. The crisis involved more than one million people seeking humanitarian protection in the EU because of the ongoing civil war in Syria as well as the atrocious violent activities of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq at the time. Expectedly, the 2015 refugee crisis has attracted considerable attention in the relevant literature with published papers focusing on different aspects its impact (inter alia: Brug & Harteveld, 2021; Holmes & Castañeda, 2016; Chouliaraki & Zaborowski, 2017; Niemann & Zaun, 2018; Thielemann, 2018).

Building on this strand of the literature, the present paper addresses the association between immigration flows and citizens’ attitudes towards national governments as well as the EU from a different angle. Specifically, it examines whether the 2015 refugee crisis affected the levels of trust towards governments and the EU. Additionally, the empirical analysis that follows also examines whether the unprecedent 2015 surge of refugees and migrants affected EU citizens’ trust towards the armed forces and the police. Both are the two pillars of states’ internal and external security and are involved in the patrol and protection of borders as well as internal law and order. As Charotte (2023) observes, irregular migration is increasingly framed as a security issue by EU’s institutions with the adoption of the concomitant policies and measures. Asderaki and Markozani (2021) point out that the 2015 refugee crisis has reinforced the securitization of the discourse and the legitimation of this discourse by the public. In a similar vein, Léonard and Kaunert (2020) also note that the 2015 refugee crisis has contributed towards a further spiraling of the securitization of the challenge posed by increasing migration flows. Τo the extent to which the surge of refugees and irregular immigrants is perceived by the EU and European citizens as a security challenge, then this perception may have influenced citizens’ trust towards these two state apparatuses. To the best of our knowledge, this is an issue that hitherto has not been empirically examined. The data used to examine the effect on EU citizens’ institutional trust levels are drawn from successive Eurobarometer surveys conducted before and after 2015. The empirical strategy to probe into the issue at hand adapts two methodologies. It first employs segmented-type regression models. As an additional step in the empirical analysis, Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition models are also estimated. The data used is briefly presented in the section that follows while in section three a bird’s eye view of the empirical methodologies used in the analysis is offered. The findings from the estimations are presented and discussed in section four while section five concludes the paper.

2 The Dataset and Descriptive Statistics

To probe into the issue at hand, data for the EU28 countries—Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Republic of Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the UK—are drawn from the Eurobarometer surveys for the time period 2010–2021. Since the UK exited the EU in 2020, we opted to include it in the analysis. The sample was chosen mainly based on the availability of information for the dependent variables, i.e. institutional trust indicators. While information for institutional trust is also available for the latest waves for 2022, there were no available data on the number of refugees for 2022, so these waves were not included in the empirical analysis that follows.

In order to compile a dataset with a large time span, all Eurobarometer waves that include information on institutional trust comprise the final sample. These are: 74.2 (2010), 75.3 and 76.3 (2011), 77.3 and 78.1 (2012), 79.1 and 80.1 (2012), 79.3 and 80.1 (2013), 82.3 (2014), 83.3 (2015), 85.2 and 86.2 (2016), 87.3 and 88.3 (2017), 89.1 and 90.3 (2018), 91.5 and 92.3 (2019), 93.1 (2020), 94.3 and 95.3 (2021). The empirical analysis concentrates on the following questions included in the Eurobarometer surveys that reflect respondents’ trust towards the national government, the EU, and the two state security apparatuses i.e. the police force and the armed forces. The question respondents reply to is as follows:

“I would like to ask you a question about how much trust you have in certain institutions. For each of the following institutions, please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it:

-

The police,

-

The army,

-

The national government,

-

The European Union”.

The respondents’ answers are categorised between “tend to trust” and “tend not to trust”. It should be noted here that the questions regarding trust towards the police and the armed forces were not included in the Eurobarometer surveys between 2011 and 2013. Thus, the econometric modelling for trust towards the police and the armed forces, involves the years 2010 and 2014–2021. In addition to the main question of interest and in line with the extant literature a number of respondents’ demographic characteristics are drawn from the surveys and are introduced as independent variables in the estimations. These indicators are the age of the respondents, their household type, the number of children in the household as well as their nationality. Furthermore, respondents’ socioeconomic characteristics such as educational level, employment class, economic hardship are included in the empirical models since they have been shown to affect individuals’ institutional trust levels. Moreover, macroeconomic indicators, drawn from the World Bank’s database are also included in the regression models. These are the unemployment rate and the annual GDP growth rate which are found to impact citizens’ (dis)satisfaction towards the national government and/or the EU and hence influence their institutional trust. Finally, the annual refugee population in a country is the main independent variable of interest in order to examine whether it affects institutional trust. However, the indicator of refugee population is likely to be an underestimation of the actual refugee inflows in the years following 2015, since there are delays in the acquisition of refugee status and in recording the number of people arriving in Europe. Both the dependent and independent variables are presented in Table 1.

In Table 2 the mean values of all dependent and independent variables are presented. The mean values are depicted for the entire period under scrutiny here, as well as for the two disaggregated sub-periods before and after the crisis. Specifically for 2010–2015 and for 2016–2021 respectively. The effect exerted by the total refugee population on the dependent variables is the principal focus of interest. As can be seen, the mean number of refugees in the EU-28 member countries in 2010 is 64,174 individuals. While the indicator might greatly underestimate the actual number of refugees in the European area, still its rapid growth in the years that follow can capture the effects on citizens’ trust levels towards the national government, the EU, the police and the armed forces. In 2015 a total of 55,591 refugees are recorded, while by 2016 the number is increased to 89,014 refugees. The number of refugees continued to increase in the following years in a steady upward trend.

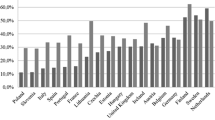

Focusing at the four institutional trust indicators it is evident from Table 2, that in all cases the mean value is higher for the years following 2015. Trust towards the police is expressed by 67% of the respondents during 2010–2015 while the respective percentage is 72.1% in 2016–2021. A comparatively smaller increase is recorded in the case of the armed forces: from 74 to 77% of the respondents tend to trust the armed forces. The largest increases in trust are observed in the case of trust towards national governments and the EU. Trust towards the national government increases from 33 to 40% in the post-2015 Eurobarometer surveys. Similarly, trust towards the EU increases from 46% of the respondents to 51%. As a preliminary step in the empirical examination of whether the 2015 refugee crisis impacted respondents’ institutional trust levels as expressed in their answers recorded by the Eurobarometer surveys, we apply chi-squared tests of independence and two tailed t-statistics for the equality of means between the treatment (2016–2021) and control (2010–2015) groups. This allows as to test whether mean institutional trust levels are significantly different between the two respective time periods. As shown in Table 2, significant test values (at the 1% level of statistical significance) are found in all cases and for both tests. It suggests that there is a statistically significant difference in institutional trust before and after 2015 that justifies the decomposition of the two groups in the next steps of the empirical analysis that follows in section four. Finally, Fig. 1 visually depicts the mean scores of respondents’ institutional trust towards the national government, the EU, the police and the armed forces (Fig. 1A–D respectively) by year, with the cut-off point set in 2015. All four figures exhibit a broadly similar pattern in time. In all cases a visually detectible discontinuity jump is present at the cut-off point of the 2015 refugee crisis.

3 The Methodology: a Bird’s Eye View

In this section, we briefly present the empirical methodologies used to examine whether the 2015 refugee crisis has affected institutional trust levels in the EU-28 countries. The four dependent variables are binary, qualitative variables: tend to trust/tend not to trust the national government, the EU, the police and the armed forces. Hence as a first step in the empirical investigation of the issue at hand, we opt to use logit models with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors. The models are estimated for the pooled sample period 2010–2021, separately for each dependent institutional trust indicator. A dummy variable for the years before and after 2015 and an interaction dummy between the latter and the refugee population are included in the estimated models to capture any effect on the dependent variables.

The second step of the empirical analysis aims to examine and quantify the relative contribution of each determinant upon individual institutional trust levels as expressed by respondents in the Eurobarometer surveys. To this effect, the standard Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition model that is widely used in similar studies is adopted (Blinder, 1973; Jann, 2008; Oaxaca, 1973). It is based on Powers et al. (2011) who provide an extension for nonlinear models. In our case, the decomposition of individual trust (the Y variables) between the time periods 2016–2021 (period A) and 2010–2015 (period B) is estimated as follows:

As seen in the previous section in Table 2, the chi-squared tests of independence and the two tailed t-statistics for the equality of means between the treatment (2016–2021) and control (2010–2015) groups, indicated that there is a statistically significant difference in institutional trust before and after 2015. This finding justifies the decomposition of the two groups. The decomposition model as depicted in Eq. (1) can provide information on the gap in the mean values of the dependent indicators between the two groups of interest. In our case, the two time periods and the concomitant Eurobarometer surveys before and after the 2015 refugee crisis. Moreover, the model also provides information on the percentage contribution in the gap that may be attributed to the differences in the observed characteristics (namely the predictors). This is known as the explained part and the gap contribution that may be attributed to the varying effects (coefficients) of these characteristics, known as the unobserved part (Malchow-Møller et al., 2009; Tzogiou et al., 2021).

The term \(\left( {\overline{{F\left( {X_{period A} \beta_{period A} } \right)}} - \overline{{F\left( {X_{period B} \beta_{period A} } \right)}} } \right)\) of Eq. (1), is the explained part or the characteristics effect. The explained part refers to the differences in the characteristics (or endowments) between the two different time groups. As Powers et al. (2011) suggests, the explained component provides information regarding the expected difference in mean outcomes if the individuals in the 2016–2021 group had a similar distribution of covariates with respondents from the period 2010–2015. In this case, a positive estimated coefficient for an independent variable indicates the expected reduction in the institutional trust gap between the two time periods, if the distribution of the independent variable during 2016–2021 was equal to the one during 2010–2015 (Sia et al., 2014; Tzogiou et al., 2021).

The second term \(\left( {\overline{{F\left( {X_{period B} \beta_{period A} } \right)}} - \overline{{F\left( {X_{period B} \beta_{period B} } \right)}} } \right)\) in Eq. (1) captures the unexplained component or the coefficients effect. The unexplained component refers to the expected difference in the institutional trust gap stemming from the differential behavioural or cultural responses to an independent indicator. In other words, each coefficient provides information on whether the behavioural/cultural response to the respective indicator during 2010–2015 was similar to the one during 2016–2021. In this case, a negative coefficient reveals the expected increase in the aforementioned gap (Abdulloev et al., 2014; Powers et al., 2011; Sia et al., 2014).

The decomposition models are popular since they can disaggregate each indicator’s contribution to the gap in the mean values of the dependent variable, but they have been subject to criticism due to certain drawbacks (Rahimi and Nazari, 2021). Specifically, the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition modelling technique is sensitive to model specification and to misspecification bias (Rahimi and Nazari, 2021; Powers et al., 2011). The non-linear Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition models as proposed by Powers et al. (2011) and Yun (2004, 2005) attempts to overcome the “identification” problem, that is causing sensitivity in the estimations based on the choice of the reference group for dummy independent indicators. In addition, the model surpasses the “indexing” problem, namely the sensitivity of estimates based on the choice of the reference and the comparison groups and the “path dependence” problem due to which the order in which the independent variables are added to the regression model affects the estimates (Gardeazabal & Ugidos, 2004; Tzogiou et al., 2021).

4 Findings and Discussion

As already pointed out in section two, the questions regarding trust towards the police and the armed forces were not included in the Eurobarometer questionnaires between 2011 and 2013. Hence all regression models presented here were estimated for the remaining years. The number of observations is 454,560 for the trust variables towards the national government and the EU and 315,844 for trust towards the police and the armed forces.

4.1 Logit Regression Results

The Logit regression findings for trust towards the national government, the EU, the police and the armed forces are presented in Table 3. As a first broad observation, the models presented in Table 3 seem to have a satisfactory fit. Starting from the main independent indicators of interest, the number of refugees seems to exert a significant impact in all dependent variables. All the coefficients are expressed in odds ratios. The refugee population seems to be positively associated with all institutional trust indices. Specifically, an increase by 1% in the refugee population is associated with 1.013 times higher chances to trust the government and 1.018 higher chances to trust the EU. Similarly, an increase in the refugee population during the years 2016–2021 is also associated with higher chances to trust the government (1.017 times higher) and the EU (1.067 times higher). The same effect is present in the case of trust towards the police and the armed forces. An increase by 1% in the refugee population is associated with 1.09 times higher chances to trust the police and 1.032 higher chances to trust the army respectively. Although the estimated effects are low in magnitude, they do indicate that a strengthening of trust towards the two state security services responsible for internal and external security is more likely to be recorded from 2016 onwards, i.e. in the post-2015 period. Similarly, the year dummy disaggregating the two time periods indicates that from 2016 onwards, there is a higher chance to trust the police (1.506 times higher) and the army (1.058 times higher) in comparison to the years before. The interaction dummy between the refugee population and the time period dummy (Refugees (ln)*Year dummy) is also associated with 1.017 higher chances to trust the national government, 1.067 higher chances to trust the EU and 1.014 times higher chances to trust the armed forces. However, the reverse effect is detected for trust towards the police. An increase in the number of refugees for the years 2016 and onwards, is associated with 0.977 times lower chances to trust the police. Nonetheless, once again the magnitude of the effect in all four cases is low.

In broad terms, the remaining estimated coefficients are in line with conventional wisdom expectations. An increase in GDP growth is associated with higher chances to trust the national government, the EU and the armed forces while the effect on trust towards the police is not statistically significant. Noteworthy is that an increase in national unemployment rates reduces trust towards the national government and the EU but increases trust towards the police and the armed forces. Once again however, the magnitude of the effect is rather small as can be seen from the odds ratios in Table 3. Respondents with higher education status exhibit greater odds to trust the national government, the police and the armed forces while no statistically significant effect is traced in the case of trust towards the EU. Higher odds to trust the institutions under consideration are found for all employment status categories in comparison to their unemployed counterparts. Except for trust towards the EU, age also exerts a positive effect on the levels of trust albeit, once again the magnitude of the effect is quite small.

4.2 Oaxaca Decomposition Results

The Oaxaca decomposition models can provide some further useful insights into the aspects of institutional trust disparities. The decomposition models can shed light on the factors that widen or reduce the gap in institutional trust before and after the 2015 refugee crisis. The estimated regressions are presented in Table 4A, B for trust towards the national government and the EU and Table 5A, B for trust towards the police and the armed forces.

As can be seen in Table 4, the mean gap in trust levels is 6.7% for government trust and 5.7% for the EU trust. The positive values indicate that trust recorded in the Eurobarometer surveys towards the national government and the EU is increased in the 2016–2021 period compared to the period 2010–2015. Trust towards the government is more than explained by differences in sample characteristics (by 122.8%). Differences in behavioural responses tend to counteract by reducing the government trust gap (− 22.8%). On the contrary, EU trust is explained by both differences in characteristics (46.65%) and by differences to cultural and behavioural responses (53.35%). The remaining 38% is explained by differences in behavioural or cultural differences, that is differences in the estimated coefficients.

The refugee indicator exerts a differential effect upon these two institutional trust indicators. If the percentage of refugee population was at the levels reported prior to 2015, then the trust towards the government would be similar which implies that the gap would decrease. However, equalising the percentage of refugee population before and after 2015 would increase the gap in EU trust. Similarly, equalising GDP growth between the two time periods, would reduce the trust gap for the government (by 2.95%) and for the EU (by 8.93%) respectively. If the unemployment levels were similar, thus higher as in the period 2010–2015, the trust levels between the two periods are expected to be more uniform and the gap in both trust indices to be lower (by 81.84% for national government trust and by 47.80% for the EU). Once again, the macroeconomic indicators seem to explain most of the trust gap that is attributed to differences in characteristics. Most of the labour market performance indicators tend to increase the gap (if equalised between the two periods), however equalising educational level and economic hardship would decrease both trust gaps.

Turning to the lower part of Table 4 that presents the gap attributed to differences in coefficients, it is evident, that most of the gap is driven by the contribution of the macroeconomic factors. In detail, equalizing the behavioural responses of the two sub-samples towards the refugee population, would decrease the trust by 87.49% towards the government and by 141.63% towards the EU. Equalizing responses to GDP growth would increase the gap by 9.72% for the national government and by 23.45% for the EU. However, equalising the unemployment responses to those estimated for the period 2016–2021 (where unemployment is lower), the trust gap towards the government would increase by 35.43% but the trust gap towards the EU would decrease by 1.30%. Equalising responses towards economic hardship and educational level, both tend to decrease the EU trust gap.

In Table 5A, B, the Oaxaca decomposition results in the case of trust towards the police and the armed forces are presented. The average gap in trust levels is 4.5% for the police trust and 2.7% for the army trust variables of interest. It indicates that on average more respondents tend to trust the two institutions from 2016 onwards. Trust towards the police is mainly driven by differences in the characteristics, with differences in the dependent variables explaining about 62% of the observed gap. The remaining 38% is explained by differences in behavioural or cultural differences, that is differences in the estimated coefficients. On the contrary, the gap in trust towards the armed forces before and after 2015 is mainly explained by differences in behavioural/cultural factors (83%) and to a lesser extent by differences in the distribution of the dependent variables (17%).

The number of refugees tends to decrease the gap by 29% for police trust and by approximately 18% for army trust. The refugee population seems to have the highest contribution in explaining the gap in individual stances in both cases. These findings mean that if respondents from the 2016–2021 Eurobarometer surveys faced the same percentage of refugees as respondents from 2010 to 2015, then their trust levels would be lower (the 2016–2021 would show less trust) and the gap in trust would be less.

Similarly, GDP growth rates between the two time periods tend to decrease the gap in police trust but increase the gap in the army trust. If respondents experienced the same unemployment between the two-time periods, then the gap would be increased in trust to the police and the army. The rest of the independent variables have a smaller contribution in explaining the observed gaps. Differences in the distribution of the employment status characteristics tend to decrease the gaps in most cases. Differences in educational levels tend to increase the gaps in trust.

Turning to the examination of the factors that contribute to the gap due to differences in coefficients between the two time periods, the results also reveal some interesting patterns. Equalizing behavioural responses of the sample between the two periods towards the refugee population would increase the gap in army trust. In other words, if the Eurobarometer surveys’ respondents of the 2016–2021 period had the same behavioural responses as the respondents of the 2010–2015 period towards the refugee population, then their army trust would be even higher. Once again, the macroeconomic variables seem to exhibit the highest contributions to the gap driven by cultural and behavioural responses.

5 Concluding Remarks

The paper examined the impact of the so called 2015 refugee crisis on individual trust towards institutions. Specifically, it focused on Eurobarometer respondents’ trust towards the national government, the EU and the two state security services, namely the police and the armed forces. The data used in the preceding empirical analysis was drawn from successive Eurobarometer surveys that had available information on individual trust towards these institutions. The sample was disaggregated into two periods 2010–2015 and 2016–2021 respectively, i.e. before and after the 2015 refugee crisis. The empirical evidence revealed a gap in institutional trust indices before and after the crisis year. In addition to the effect of the 2015 refugee crisis, the paper also examined the relevant contribution of several macroeconomic and microeconomic factors to the observed trust gap.

As an overall observation based on the results reported herein, it seems that the number of refugees is associated with higher chances to trust the police, the armed forces, the national government and the EU. The increase in the number of the refugees’ population from 2016 onwards is associated with a higher probability to trust the security services, the government and the EU. Although all the estimated effects are low in terms of magnitude, they nonetheless indicate a strengthening of the public sentiment towards institutions that have a role in the mediating and restricting the flaw of migrants and refugees. Thus, one could tentatively conclude that the findings appear to render support in favour of a “rally-around-the flag” effect when it comes to the levels of trust recorded in respondents’ answers to the relevant questions in the Eurobarometer surveys. Expectedly, improved economic performance as encapsulated by the growth rate of GDP also has an augmenting effect on institutional trust level. On the other hand, an increase in the unemployment rate seems to be associated with lower trust levels towards the national government and the EU but not so in the case of trust towards the security services. In general, the more educated and well-off Eurobarometer respondents are, they tend to exhibit higher institutional trust.

The decomposition analysis also shows that trust levels increased since 2016 for all trust indicators examined herein. The macroeconomic indicators seem to explain most of the observed trust gap. The refugees’ population also explains a large part of the observed gap in trust levels. Equalising the percentage of refugees before and after 2015 would decrease the gap in institutional trust towards the army, the police and the government, but it would increase the gap in trust towards the EU. Differences in the reactions towards the refugee populations between the time periods examined also tend to increase the gap in army trust but they tend to decrease the gap in trust towards the government and the EU. National economic conditions also explain a large part of the gap, in terms of both differences in characteristics and differences in reactions to these characteristics.

Overall, the empirical results reveal a “rally around the flag” finding, with increased support to national institutions (government, police, armed forces), but less support to EU institutions. It appears that the results reported herein accord with those of previous studies showing that events that have the potential to increase citizens’ risk perceptions and insecurity have a tendency to augment national identity feelings and generate a “rally around the flag” reaction.

The results reported herein accord with conventional wisdom and are in line with previous research findings showing that geopolitical shocks, in this case the 2015 refugee crisis, tend to affect institutional trust levels and subsequently the public’s attitudes towards intergovernmental organizations such as the EU, states and states’ institutions. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the methodological modelling followed herein has shortcomings that need to be mentioned. The sample formulation was based on the availability of institutional trust information in all Eurobarometer waves. The aim was to compile a dataset with the longest time span possible, in order to better capture the effects of the upward trend in refugee inflows after 2015. This data formulation limits the availability of information on significant trust determinants, including individual political values, political self-placement and policy preferences that have been shown in the relevant literature to affect citizens’ institutional trust levels. Additionally, the number of refugees variable is probably underestimated. Consequently, the effects reported above may also underestimate the impact of the refugee crisis on institutional trust. Even so, the results of the models shed some additional light on the relationship between the refugee inflows and the formation on trust towards institutions in the EU countries.

References

Abdulloev, I., Gang, I. N., & Yun, M.-S. (2014). Migration, education and the gender gap in labour force participation. European Journal of Development Research, 26, 509–526.

Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trusts others? Journal of Public Economics, 85(2), 207–234.

Arpino, B., & Obydenkova, A. (2020). Democracy and political trust before and after the Great Recession 2008: The European Union and the United Nations. Social Indicators Research, 148, 395–415.

Art, D. (2018). The AfD and the end of containment in Germany? German Politics and Society, 36(2), 76–86.

Arvanitidis, P., Economou, A., & Kollias, C. (2016). Terrorism’s effects on social capital in European countries. Public Choice, 169(3–4), 231–250.

Asderaki, F., and E. Markozani (2021). The Securitization of Migration and the 2015 Refugee Crisis: From Words to Actions, in The New Eastern Mediterranean Transformed, edited by Tziampiris, A. and F. Asderaki. Cham: Springer.

Bækgaard, M., Christensen, J., Madsen, J. K., & Mikkelsen, K. S. (2020). Rallying around the flag in times of covid-19: Societal lockdown and trust in democratic institutions. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration. https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.32.172

Berrebi, C., & Klor, E. (2008). Are voters sensitive to terrorism? Direct evidence from the Israeli electorate. American Political Science Review, 102(3), 279–301.

Bjornskov, C. (2006). The multiple facets of social capital. European Journal of Political Economy, 22(1), 22–40.

Blinder, A. S. (1973). Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. The Journal of Human Resources, 8(4), 436–455.

Bobzien, L. (2023). Income inequality and political trust: Do fairness perceptions matter? Social Indicators Research, 169, 505–528.

Bove, V., & Di Leo, R. (2020). COVID-19, security threats and public opinions. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 26(3), 20200033.

Brosius, A., van Elsas, E., & de Vreese, C. (2019). Trust in the European Union: Effects of the information environment. European Journal of Communication, 34(1), 57–73.

Brug, W., & Harteveld, E. (2021). The conditional effects of the refugee crisis on immigration attitudes and nationalism. European Union Politics, 22(2), 227–247.

Caïs, J., Torrente, D., & Bolancé, C. (2021). The effects of economic crisis on trust: Paradoxes for social capital theory. Social Indicators Research, 153, 173–192.

Charotte, D. (2023). The nexus between asylum seekers and defence spending in European NATO member states: A quantitative study of securitisation dynamics. Defence Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2023.2296893

Chouliaraki, L., & Zaborowski, R. (2017). Voice and community in the 2015 refugee crisis: A content analysis of news coverage in eight European countries. The International Communication Gazette, 79(6–7), 613–635.

Davvetas, V., Ulqinaku, A., & Abi, G. S. (2022). Local impact of global crises, institutional trust, and consumer well-being: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of International Marketing, 30(2), 73–101.

Economou, A., & Kollias, C. (2019). Security policy preferences of EU citizens: Do terrorist events affect them? Public Choice, 178, 445–471.

Economou, A., & Kollias, C. (2023). In NATO We Trust(?): The Russian Invasion of Ukraine and EU27 Citizens’ Trust in NATO. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 29(2), 129–144.

Ervasti, H., Kouvo, A., & Venetoklis, T. (2019). Social and institutional trust in times of crisis: Greece, 2002–2011. Social Indicators Research, 141, 1207–1231.

Gardeazabal, J., & Ugidos, A. (2004). More on identification in detailed wage decompositions. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(4), 1034–1036.

Getmansky, A., & Zeitzoff, T. (2014). Terrorism and voting: The effect of rocket threat on voting in Israeli elections. American Political Science Review, 108(3), 588–604.

Hall, J., & Werner, K. (2022). Trauma and trust: How war exposure shapes social and institutional trust among refugees. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 786838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.786838

Harteveld, E., Meer, T., & Vries, C. (2013). In Europe we trust? Exploring three logics of trust in the European Union. European Union Politics, 14(4), 542–565.

Helbling, M., Meierrieks, D., & Pardos-Prado, S. (2023). Terrorism and immigration policy preferences. Defence and Peace Economics, 34(5), 646–659.

Hobolt, S., & Wratil, C. (2015). Public opinion and the crisis: The dynamics of support for the Euro. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(2), 238–256.

Holmes, S. M., & Castañeda, H. (2016). Representing the ‘European Refugee Crisis’ in Germany and Beyond: Deservingness and Difference Life and Death. American Ethnologist, 43(1), 12–24.

Jann, B. (2008). The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. The Stata Journal, 8(4), 453–479.

Jeannet, A., Heidland, T., & Ruhs, M. (2023). A need for control? European Political Science Review: Political trust and public preferences for asylum and refugee policy. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000012

Keele, L. (2007). Social capital and the dynamics of trust in government. American Journal of Political Science, 51(2), 241–254.

Kim, Y., Sommet, N., Na, J., & Spini, D. (2022). Social Class—not income inequality—predicts social and institutional trust. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(1), 186–198.

Knudsen, E., Nordø, D. Å., & Iversen, M. H. (2023). How rally-round-the-flag effects shape trust in the news media: Evidence from panel waves before and during the covid-19 pandemic crisis. Political Communication, 40(2), 201–221.

Koos, S., & Seibel, V. (2019). Solidarity with refugees across Europe: A comparative analysis of public support for helping forced migrants. European Societies, 21(5), 704–728.

Léonard, S., & Kaunert, C. (2020). The securitisation of migration in the European Union: Frontex and its evolving security practices. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(6), 1417–1429.

Malchow-Møller, N., Munch, J. R., Schroll, S., & Skaksen, J. R. (2009). Explaining cross-country differences in attitudes towards immigration in the EU-15. Social Indicators Research, 91(3), 371–390.

Mihalik, J. and J. Bardovic (2019). [Eds] Migration: The Challenge of European States, ibidem Press, Stuttgart.

Newton, K., & Zmerli, S. (2011). Three forms of trust and their association. European Political Science Review, 3(2), 169–200.

Niemann, A., & Zaun, N. (2018). EU refugee policies and politics in times of crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(1), 3–22.

Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14(3), 693–709.

Powers, D. A., Yoshioka, H., & Yun, M. S. (2011). Mvdcmp: Multivariate decomposition for nonlinear response models. The Stata Journal, 11(4), 556–576.

Rahimi, E., & Hashemi Nazari, S. S. (2021). A detailed explanation and graphical representation of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition method with its application in health inequalities. Emerging Themes Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-021-00100-9

Rommel, I. (2017). We are the People”. Refugee–’crisis’, and the drag-effects of social habitus in German Society. Historical Social Research/historische Sozialforschung, 42, 133–154.

Scipioni, M., Tintori, G., Alessandrini, A., Migali, S. and Natale, F. (2019). Immigration and trust in the EU, EUR 30042 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, ISBN 978-92-76-14661-2, https://doi.org/10.2760/76114

Sia, D., Onadja, Y., Nandi, A., Foro, A., & Brewer, T. (2014). What lies behind gender inequalities in HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan African countries: Evidence from Kenya. Lesotho and Tanzania, Health Policy and Planning, 29(7), 938–949.

Stockemer, D., Niemann, A., Rabenschlag, J., Speyer, J., & Unger, D. (2018). Immigration, anti-immigrant attitudes and Eurosceptism: A meta-analysis. French Politics, 16(3), 328–340.

Stockemer, D., Niemann, A., Unger, D., & Speyer, J. (2020). The ‘refugee crisis’, immigration attitudes, and euroscepticism. International Migration Review, 54(3), 883–912.

Thielemann, E. (2018). Why refugee burden-sharing initiatives fail. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(1), 63–82.

Tormos, R. (2019). Measuring personal economic hardship and its impact on political trust during the Great Recession. Social Indicators Research, 144, 1209–1232.

Tzogiou, C., Boes, S., & Brunner, B. (2021). What explains the inequalities in health care utilization between immigrants and non-migrants in Switzerland? BMC Public Health, 21, 530–545.

Uslaner, E. (2002). The Moral Foundations of Trust. Cambridge University Press.

Uslaner, E. (2008). The foundations of trust: Macro and micro”. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 32(2), 289–294.

Vasilakis, C. (2018). Massive migration and elections: Evidence from the refugee crisis in Greece. International Migration, 56(3), 28–43.

Vreese, C. (2017). How changing conditions make us reconsider the relationship between immigration attitudes, religion, and EU attitudes. European Union Politics, 18(1), 137–142.

Yun, M.-S. (2005). A simple solution to the identification problem in detailed wage decompositions, Economic Inquiry, 43: 766–772. With Erratum, Economic Inquiry 44: 198.

Yun, M.-S. (2004). Decomposing differences in the first moment. Economics Letters, 82, 275–280.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge insightful comments and constructive suggestions by two anonymous referees as well as comments by participants of the conference “The National Security State: Institutional Causes and Consequences”, Department of Economics, New York University, 27-28 April 2023. The usual disclaimer applies.

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose nor any conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Economou, A., Kollias, C. The 2015 Refugee Crisis and Institutional Trust in European Countries. Soc Indic Res 173, 377–396 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03348-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03348-1