Abstract

Over the last two decades, involuntary part-time (IPT) employment has become a more and more pressing issue in Europe, especially in the southern countries, where IPT today constitutes most part-time employment. Using INAPP-PLUS data and different discrete choice model estimations, this paper aims to shed light on the factors that explain the IPT growth in Italy, focusing on what influences the IPT status at the individual, household and labour market levels. The main hypothesis is that what influences the IPT work derive from a combination of workers’ individual, household, and job characteristics which may engender limited power during the bargaining process. The empirical results, based on gender-specific models, highlight that characteristics associated with the IPT status significantly changed over time, reporting a convergent path between the gender profiles of IPT employment. However, IPT employment for women still appears to be mainly originated from the gendered division of domestic and care tasks, while this phenomenon seems to be mainly driven by the labour demand side for men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the last two decades involuntary part-time (IPT) employment has become a more and more pressing issue in Europe. After the 2008 crisis, net job destruction coincided with an increase in insecure employment and under-employment in involuntary part-time work (European Commission, 2014). The latter has been notably prominent in the Southern part of the continent, especially in Italy and Spain (Fellini & Reyneri, 2018; Leschke, 2013; Nicolaisen et al., 2019), where IPT represents today the majority of the part-time employment; this is to say that in these countries most of those who work less, would like to work more. The negative consequences of the growth of this phenomenon, however, may not be solely related to the workers’ dissatisfaction in terms of the number of hours of job availability.

Filandri and Struffolino (2019) find that among European countries, involuntary part-time and female involuntary part-time employment, in particular, is an essential element of segregation and dualization of the labour market, especially in terms of in-work poverty.

Despite its growing importance, albeit particularly geographically located, IPT constitutes a recent research area, either among the scientific literature or public debate. Our article aims to support the comprehension of this phenomenon by deepening the knowledge of IPT. The article’s main aim is to analyse the individual, household, and job characteristics related tothe IPT employment. In contrast, structural and macro determinants of this phenomenon are considered in the background of this study. This article also advances the literature by conducting separate analysis for men and women, contributing to a small but growing evidence base on part-time employment for men (Belfield et al., 2017; Gardiner & Gregg, 2017; Nightingale, 2018; O’Dorchai et al., 2007).

Therefore, the two research questions guiding our analysis are as follows. What are the main (micro) drivers of the involuntary part-time employment in Italy, and how did they evolve in the great economic crisis? How do the profiles of involuntary part-time workers, particularly in relation to job and household characteristics, vary according to gender?

While Italy is an emblematic case for analysis of this issue,Footnote 1 this study can also provide a benchmark for figuring out the prospects for the European labour market. As the Italian case suggests, it is possible to expect that the positive trend of unemployment reduction and job creation experienced at the European level, especially in the first two quarters of 2021 according to data from the European Labour Market Barometer, was in part prompted by demand for non-standard occupations. Furthermore, the potential structural labour market modification prompted by the COVID-19 outbreak in the medium and long run will impact the characteristics of the labour markets in most European countries. A recent scenario developed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics concerning the long-run impacts of COVID-19 in the US labour market highlights growing uncertainty connected to a potential increase in insecurity and non-standard jobs in several low-skilled occupations (Ice et al., 2021). Considering the high share of low-skilled workers among IPT workers (Kauhanen & Jouko, 2015; Tilly, 1996; Warren & Lyonette, 2018), studying the evolution of IPT profiles in Italy provides elements to understand the impact of possible trends that the labour market will have to cope with in the near future. This article also advances the literature by conducting separate analyses for men and women, contributing to a small but growing evidence base on part-time employment among men (Belfield et al., 2017; Gardiner & Gregg, 2017; Nightingale, 2018; O’Dorchai et al., 2007).

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review of IPT studies focusing on what mainly influences the IPT status. Section 3 discusses the case of Italy. Section 4 develops the main thesis of the paper and provides a description of both the data and methods adopted. Section 5 shows the results of our empirical analyses and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Literature Review

Traditionally, as Nicolaisen et al. (2019) note, there have been two main types of explanation for why people work part-time. One is related to demand factors and emphasises the influence of market conditions, occupational structures and labour cost (O’Reilly & Fagan, 1998; Tijdens, 2002; Wielers et al., 2014). The other focuses on supply-related factors such as the employee’s work-life balance and education, and the sharing of domestic responsibilities by couples (see, among others, Blossfeld & Hakim, 1997; O’Reilly & Fagan, 1998). Women have always been more inclined/exposed to part-time employment thanks/due to its role in easing the work-life balance (Nicolaisen et al., 2019). This well-known background allows studying the phenomenon of the recent steady and steep increase in involuntary part-time work in Italy through the intersection of these theories. This section aims to identify the drivers of involuntary part-time work focusing on two dimensions: individual and household characteristics; job characteristics.

2.1 Individual and Household Characteristics

An analysis carried out by Borowczyk-Martins and Lalé (2016) on the situation of involuntary part-timers using Current Population Survey (CPS) data, a primary source of labour force statistics on the US population, helps identify the crucial characteristics of these workers. The authors compare the individual socio-economic characteristics of three broad groups, namely part-timers, involuntary part-timers and the unemployed.Footnote 2 The descriptive analysis reveals an interesting convergence between the last two groups in terms of several characteristics such as gender, age distribution, education and marital status.

Compared to voluntary part-timers, involuntary ones are more likely to be male, aged in their prime, with lower education levels and not in a couple. According to the CPS data, around 60% of the individuals who declared they worked in IPT status reported having a high school certificate or had stopped schooling before obtaining this grade, compared to 42% of those who voluntarily chose to work part time. More than a third of voluntary part-timers (37%) are between 16 and 24 years old, an age in which a reduced work commitment makes following alternative pathways—like education—easier. Although an important quota (30%) of involuntary part-timers are in the same age group, the majority are young adults or adults aged 25–54.

Concerning gender evidence indicates that among US employees the well-known strong unbalanced distribution toward female workers that characterises part-time employment is much less pronounced when IPT work is considered (Borowczyk-Martins & Lalé, 2016; Valletta et al., 2020). The CPS data show that the 40% gender divide among voluntary part-timers drops to 10% when the focus is on IPT workers, with female workers still being the largest group (55.3%), but not much larger than the male group (44.7%).

According to the Borowczyk-Martins and Lalé (2016), slightly less than two-thirds of involuntary part-timers are single, divorced or widowed, while among voluntary part-timers around half of them are. However, regardless of their gender an important share of IPT workers live in a couple (Valletta et al., 2020) and given the average age of this group of workers it is possible to assume that many of them live in a household with children of school age. Therefore, like part-time employment, IPT occupations are also driven by within-couple sharing of domestic labour and hence are strictly related to child-related care burdens (Blossfeld & Hakim, 1997; O’Reilly & Fagan, 1998).

Following this line of reasoning, other household features related to the impossibility of reconciling work and family issues and the (un)fair distribution of family and work responsibilities between genders (Blossfeld & Hakim, 1997; Lyonette, 2015; O’Reilly & Fagan, 1998; Rosenfeld & Birkelund, 1995) need to be take into account. Several factors can be considered when analysing the impact of family issues on working careers, but evidence shows the importance of focusing on the relative (motherhood) earnings penalty (Dotti Sani, 2015) to account for different economic bargaining powers within the couple when reconciliation issues need to be addressed. Being the primary or secondary earner in a couple can influence career decisions in the medium and long term (Dotti Sani & Luppi, 2021), therefore affecting the possibility of being a full-time employee.

Another factor that seems to influence the probability of being in part-time employment is the worker’s migration background. This stands out as an important element as migrants tend to be over-represented in part-time positions and work involuntarily as part-timers more often than natives do (OECD, 2010; Rubin et al., 2008).

2.2 Job Characteristics

Nicolaisen et al. (2019) propose a comprehensive typology of part-time workers by looking at their voluntary vs involuntary nature and the quality of their working conditions, identifying three categories connected to the involuntary nature of part-time jobs. Unlike the first typology, which are part-timers with the same working conditions and social protection as full-time workers but who would like or need to work more hours, the other two typologies are part-time jobs marked by bad or terrible working conditions.

While in the primary labour market good part-time work responds to a need to attract and retain core workers who for some reason cannot or will not enter in a full-time contract (see, e.g., Tilly, 1996; Blossfeld & Hakim, 1997; Webber & Williams, 2008), in the secondary labour market part-time jobs are offered with poorer conditions to increase the numerical and financial flexibility firms require to perform in the market (Atkinson, 1984; Tilly, 1996). This type of part-time employment is characterised by low-quality working conditions and social protection, and often by an exceptionally low number of contracted hours (Blossfeld & Hakim, 1997; O’Reilly & Fagan, 1998).

These considerations suggest that while ‘good’ part-time occupations and (temporarily) underemployed part-timers tend to be transversal to the job market, IPT jobs (especially if they present features of insecurity) tend to be concentrated in specific segments of the workforce and industrial sectors.

Regarding the US labour market, Valletta and van der List (2015), analysing Current Population Survey (CPS) monthly data from 2003 to 2016, point out that the prevalence of IPT work is especially high in certain service industries, notably the retail and leisure/hospitality sectors. Similarly, a not recent but still crucial analysis of the quality of part-time work in the UK (Lyonette et al., 2010), based on UK Labour Force Survey data, points in the same direction. In the UK, a high proportion of part-time workers were concentrated in the leisure and hospitality sectors, together with wholesale, retail, motor trade and other community, social and personal occupations. Additionally, beside industrial sectors, research suggests two further differentiations concerning the influence of structural elements on part-time employment: private vs public sectors, and large vs small enterprises. Europe-wide research undertaken by Anxo et al. (2007) at the firms level found that in almost all the countries involved in the analysis there were higher levels of part-time work in the public sector than in the private sector, mainly driven by a higher share of women working in the public sector than in the private one.

Concerning this differentiation, there are opposite findings. Anxo et al. (2007), in their study based on a representative sample of establishments with ten or more employees in 21 European countries, highlighted that larger numbers of part-time workers are found in large organisations. In contrast, using the UK Labour Force Survey Lyonette et al. (2010) found that smaller organisations (under 50 employees) overall represent the predominant type of firms employing part-time workers. Despite this difference between the UK and other European countries, research finds similarities among European countries regarding the types of organisations more likely to employ part-time workers. Overall, organisations are more likely to have part-time workers if they are large companies operating in the service sector. In fact, organisations with a high rate of part-time employment are concentrated in the following sectors: health and social work; education; other community, social and personal services; and hotels and restaurants (Anxo et al., 2007). Although these figures concern the whole subgroup of part-timers and not only of those of an involuntary nature, the derived considerations provide valuable elements for comprehending the latter.

The international literature suggests that IPT workers tend to be young adults living in couples, often with a fragmented family history, poorly educated and with a high probability of having a migrant background. Furthermore, despite the lower probability of IPT workers being women compared to part-time employment in general, IPT work is still driven by the worker’s share of household responsibility and being the second earner.

Regarding labour market determinants, although the picture seems slightly divergent between the US and the European labour markets, IPT workers seem to be more prevalent in large (private) companies operating in specific sectors, such as healthcare, services and hospitality.

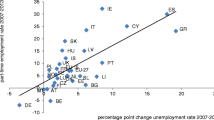

3 IPT in Italy: A Comparison with European Countries and Across Populations

On average, in the OECD countries, 16.3% of part-time workers are involuntary and the share of IPT workers increased substantially between 2007 and 2016. There is, however, a considerable discrepancy between the countries contributing to this average. In countries like Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, the US and Norway, the levels of IPT work are well below 15% of all part-time employees and there was only a slight (or no) increase after 2007 (Nicolaisen et al., 2019). At the other end of the scale, in southern European countries like Greece, Spain and Italy, which were hit harder by the economic crisis, more than half the part-time workers would like to work longer hours and the share of IPT work increased substantially in the same reference period (Nicolaisen et al., 2019).

The last two reports by the Italian National Council for Economics and Labour (CNEL) indicate that the primary effect of the Great Recession on the Italian labour market was a severe rise in IPT work (Fellini & Reyneri, 2018), rather than an increase in insecure full-time jobs. While the overall number of employees in 2018 was slightly higher than in 2008, the composition of the workforce was significantly different. In the post-recession phase, the new phenomenon which characterised the Italian labour market was an increase in part-time jobs, especially involuntary ones (Fellini & Reyneri, 2018). Similarly to other countries, in Italy this growth in IPT jobs mainly interested the tertiary sector (e.g. trade, hospitality, transportation and personal services), with a predominance of ‘bad’ occupations in terms of both remuneration and job mismatch.

However, the tendency toward an increase in part-time occupations, both voluntary and involuntary, started before the Great Recession in Italy. Although Italy can be considered a latecomer in terms of the expansion of part-time occupations (although with a marked catch-up with the growing European trend starting in 2004), the evolution of part-time jobs has followed a different path compared to the European average tendency. The growth in part-time jobs among Italian workers aged 15–64 appears to be particularly related to the sudden rise in part-time employment reported by females in the period 2003–2004. (Fig. 2 in the Appendix).

At the beginning of the century, IPT jobs already represented an important share of part-time employment in Italy (33.3%), a value almost double that reported by the Eurozone as a whole (18.9%) (Fig. 3 in the Appendix). In the following years, and especially during and after the economic crisis, the share of IPT work in part-time employment dramatically rose, reaching an incidence steadily higher than 65% from 2014 onwards (except for a slight reduction in the period 2016–2017). Apart from Spain, which presented a similar behaviour except for a turnaround in 2018, other European countries reacted to the economic crisis differently. Indeed, while a general rising trend of IPT work marked by different intensities is detectable until 2014, in the following years (with some countries beforehand, like Germany and the UK, and some afterwards, like France) a progressive reduction in this type of occupations occurred (Fig. 3 in the Appendix).

On the contrary, Italy has been characterised by an exceptional increase in IPT occupations in the last two decades that interested, in a similar manner, both male and female workers (Fig. 4 in the Appendix). Male IPT workers increased in number by 28.7 percentage points (p.p.) from 2004 to 2019, whereas IPT work grew by 27.6 p.p. among females in the same period. It should be noted that the relative increase in the IPT share of total part-time employment is, however, higher among female workers than male ones: 83% and 61% respectively. In addition, women constitute by far the largest group among IPT workers: in the 15 years considered, women have never been less than two-thirds of total IPT workers. This is easily explained by considering the different ‘attraction’ of part-time occupation between genders. In 2019, more than 30% of women were employed part-time, whereas this share was below 10% among men. Therefore, even considering the lower female participation in the labour market—in 2019 female workers constituted around 42% of the total labour force in Italy (data provided by the Italian National Institute of Statistics)—in absolute terms the number of total female workers in part-time employment was around three-times higher than that of men. In conclusion, even if women are the majority of IPT employees in Italy, it is more likely for a man to be an IPT worker than a voluntary part-time worker.

A further crucial element in the Italian IPT landscape which also shares a thread of similarity with the trend in gender distribution concerns territorial differences. During the last two decades, the highest growth in IPT occupations in total part-time employment concerned the territorial areas in which the phenomenon was less present in 2004 (Fig. 5 in the Appendix).

Considering the magnitude of the impact of COVID-19 on the (Italian) labour market, it is of primary importance to detect the individual characteristics of IPT and how they changed after the last economic crisis impacted the national economy before the pandemic: the Great Recession.

What are the individual characteristics that explain this phenomenon in Italy and how did they change over the last decade and, more particularly, how do they diverge in terms of gender?

Our main hypothesis is that what influences the IPT work derives from a combination of workers’ individual and household features and their professional sector and status, characteristics which engender limited bargaining power that negatively affects workers’ earnings. We expect that workers with more bargaining power in the job market, like those with a degree and high skills, enjoy more freedom of choice in fulfilling their preferences than workers in a weaker position who cope with a greater degree of constraints. In other words, our hypothesis is that, as the literature suggests, Italian IPT workers are, in average terms, in a more insecure condition compared to voluntary part-timers and that their status is detectable by the drivers of IPT.

Furthermore, in bigger firms and in more structured sectors (such as manufacturing and financial and professional services) IPT workers are less likely to be found than in the personal care and service industry, and in small firms.

At the same time, it is possible to assume that individual features impact preferences regarding the number of working hours. As the literature indicates, reconciling work and family life issues constitutes, especially for women, a major shove toward part-time employment since this solution tends to be the outcome of an individual/household strategy (Wielers et al., 2014). However, the embeddedness of this solution in the cultural acceptance of part-time work in different societies could limit women’s perception of the involuntariness of their choice (ibidem). At the same time there are discrepancies in different societies of the part-time outcome in terms of segregation (Barbieri et al., 2019). In this regard, we hypothesise that, considering the familialism tradition in Italian culture and the Italian welfare state (Ferrera, 1996; Saraceno & Keck, 2010) and women’s disadvantage in the labour market (Barbieri, 2011), female IPT workers are exposed to a higher risk of insecurity compared to female PT workers than male IPT workers compared to male PT workers. Female IPT workers are expected to be featured by limited bargaining power compared to their male counterparts, which can lead to a larger and more stable risk of IPT than male workers. For the latter, the IPT risk can be more circumscribed and related to a specific stage of life or particular occupations. Instead, the probability of being in IPT employment can be more transversal and widespread among women.

4 Data and Methods

Our analysis relies on a pooled cross-sectional dataset from the Participation, Labour and Unemployment Survey (PLUS) conducted by the Italian National Institute for Public Policies Analysis (INAPP). These data provide reliable statistics on labour market phenomena which are rare and are more marginally explored than the much better known Eurostat Labour Force Survey, such as on intergenerational mobility, IPT and educational mismatch. The INAPP-PLUS survey also contains information on a wide range of standard individual characteristics and a number of characteristics related to professions and firms for at least 35,000 individuals in each wave. A dynamic computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) approach was used to distribute the questionnaire to a sample of residents aged 18–74 selected through stratified random sampling of the Italian population.Footnote 3 The INAPP-PLUS datasets provide individual weights to account for non-response and attrition issues, which usually affect sample surveys. Similarly to other empirical studies relying on the same dataset (see, among others, Clementi & Giammatteo, 2014; Filippetti et al., 2019; Bonacini et al., 2021), all descriptive statistics and estimates reported in this analysis are weighted using these individual weights.

We use three waves of the INAPP-PLUS survey: one before the crisis (2006), one during the crisis (2011), and one after the crisis (2018).Footnote 4 From the initial samples of individuals, we select those who were both employed and aged between 18 and 64. Then, among the observations satisfying these criteria we focus on individuals declaring they have part-time employment. The INAPP-PLUS survey asks part-timers the following question:

Why do you have a part-time employment…?

1. By your choice or convenience; 2. Because your employer requested it.Footnote 5

We consider those who replied that they had this type of employment because their employer requested it to be involuntary part-timers. As we cannot interpret missing values in any clear direction, we decide to drop observations not responding to this question. Our final sample consists of 1997 observations in the 2006 sample, 2151 in the 2011 one, and 3160 in the 2018 one.

The econometric analysis regarding what influences the probability of having part-time employment involuntarily is developed through estimation of Probit models which present the following specification for each observation i:

where the dependent variable IPT is a dummy equal to 1 if the part-time job is involuntary and 0 otherwise (i.e. voluntary part-time), X is a vector of relevant covariates suggested by the literature. In this analysis we provide two different specifications for the vector X: a vector of individual and household characteristics (i.e. gender, age, citizenship, education level, marital status, employment status of the partner, number of children, presence of disabled family members, tenure status, municipality size and macro-region of residence); a vector of job characteristics (i.e. job relationship tenure, occupation skill level, type of employment contract, firm size and activity sector). A detailed description of the variables used in our analysis is presented in the Appendix (Table 5). The first model specification is labelled as Model 1 and the second model specification as Model 2 henceforth. Model 1 investigates what individuals’ characteristics correlate more with a higher labour market vulnerability in terms of involuntariness of part-time employment, while Model 2 does the same for the occupation and labour demand characteristics.Footnote 6

To explore the extent of gender heterogeneity in our main results, the above-presented econometric analysis is applied by means of separate regressions for men and women on the probability of involuntarily having a part-time job (rather than voluntarily).Footnote 7 In this case, we mainly focus on the main (I)PT ‘gender-related’ factors such as marital status, presence of underage children and partner’s occupational status. Also, to investigate whether characteristics associated with the IPT phenomenon in Italy changed over time, we replicate the analysis for each of the three years considered.Footnote 8

In the end of the econometric analysis, as a robustness check of our main results, we explore what influences the probability of having an IPT employment also exploiting as alternative status the full-time employment. To do that, we estimate multinomial Logit models where the set of covariates adopted remains the same of the main analysis and the dependent variable presents three different outcomes: i) having full-time employment; ii) having a part-time employment voluntarily; iii) having a part-time employment involuntarily. In the estimates, the first outcome (i.e. being full-timers) represents the base one. Again, this econometric analysis is replicated by gender and year. Results of this sensitivity analysis are presented in Sect. 5.3.

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive Statistics

For the sake of brevity Tables 1 and 2 only show the composition of two samples (the 2006 and 2018 ones) and focus on part-timers, differentiating by their voluntary or involuntary nature, presenting a number of individual, household and labour characteristics. These tables allow a double reading of the phenomenon of our interest, a comparison across (and within) genders of the IPT worker’s profiles, also in relation to the characteristics of the overall part-timers, and across time to look at the evolution of IPT worker’s profiles.

Concerning the time trend, Tables 1 and 2 suggest a common trend across genders: between 2006 and 2018, the IPT workers’ profiles became more transversal to the socio-economic and labour market characteristics considered. Albeit presenting different characteristics, female and male IPT workers in the decade considered show a general diffusion concerning several aspects considered. In 2006, those who accepted part-time employment involuntarily were younger than the overall subgroup of part-timers, particularly women, where more than 55% were aged below 35. In 2018, IPT workers, both male and female, are more evenly distributed across age, with the majority of them aged between 26 and 50 years.

In the two years considered, male IPT workers registered an increase in those not married, reaching almost 70%; the opposite is true for women. Female IPT workers show a decrease of nine percentage points between the two periods analysed. However, a significant reduction, higher than ten percentage points, in the share of single-earner IPT workers, those married with an unemployed partner, is detectable in both genders. The presence of children in the household changed significantly in the two waves analysed, not only for IPT workers but in the overall subgroup of part-timers, especially for men. While in 2006, part-time employment, regardless of its involuntary nature, was almost exclusively related to living with one or more children, in 2018, the picture is reversed: nearly 70% and 46.1%, respectively, for male and female IPT workers, live in a household without children. A similar trend, marked by a significantly lower intensity, is also detectable among those who care for a disabled person.

A further significant variation concerns the housing tenure arrangements. The share of homeownership rises by a factor of 3.5 among male IPT workers and 2.6 for their female counterparts, with a percentage higher than 80% in both cases. The predominance of involuntary part-time employment in the south of Italy and the metropolitan area decreases between 2006 and 2018 for male and female workers, showing a more even distribution for both territorial characteristics.

As for labour characteristics, descriptive statistics indicate that the already high share of men and women with low occupational skills employed in IPT conditions in 2006 further enlarged in 2018, contrary to what was observed for the overall subgroup of part-timers, where a more stable trend is detectable. On the other hand, both male and female IPT workers are more likely to be in an open-ended contract in 2018 than in 2006, as a consequences of the relative reduction of those in fixed-term contracts. A further shared trend between genders emerges when looking at company size: the relative share of IPT workers operating in small firms (below 14 employees) increased by fifteen percentage points between 2006 and 2018. Against a more or less stable distribution of part-timers between 2006 and 2018 in terms of economic sectors, IPT employment has been driven by personal services and social services sectors for female workers and personal services and services–distribution sectors in the case of male labourers, with a higher probability of operating in the private sectors compared to public one.

Finally, workers with IPT status report shorter tenure in the same firm and a slightly higher average value of weekly hours worked. Annual gross labour income indicates an interesting change, especially regarding gender. While, in 2006, on average, IPT workers earned more than the part-timers, with limited gender difference, in 2018, this difference is inverse and more pronounced, with IPT average earnings below those of the overall part-timers, especially for women.

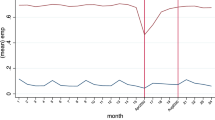

Descriptive statistics highlight a certain similarity in the spread trend of IPT across gender. Figure 1 allows a better understanding of this dynamic regarding age distribution by looking at the relative incidence of IPT on total part-timers, differentiating for gender and years considered.

Figure 1 suggests that, between 2006 and 2018, the relative incidence of IPT employment among women significantly rose, especially among the young population (below 35 years), reaching, for the latter, similar values of the male ones, which, contrary, already showed high percentages in 2006. However, the female distribution remains more or less similar in the two years considered, showing a partial U shape with high incidence in the younger age, an important drop for adult workers, and a slight, especially in 2018, increase among the older population segments. Conversely, male IPT workers, especially in 2018, are more evenly distributed regarding age, showing that the probability of being an IPT occupation is not a trait that interests a specific age group.

5.2 Econometric Analysis

The estimation results in Table 3 confirm most of the preliminary findings presented above, but some noteworthy changes in the IPT drivers occur over time.Footnote 9 The age coefficients confirm the higher probability of involuntary part-time employment in women’s early stages of working careers (i.e. those aged 26–35 years old). In contrast, findings do not point clearly in this direction for male workers except for the year 2018. Furthermore, female graduate workers consistently report—ceteris paribus—a lower probability of being hired involuntarily with a part-time contract, whereas this result is statistically significant only for 2018 for the male counterparts. Living in an owned house, and so having a certain level of household wealth, always seems to make part-time employment more acceptable or at least less involuntary for female workers, even though this effect decreases over the period analysed (especially for male workers). Living in southern regions engenders ceteris paribus a higher probability of IPT work status than living in the north-west of Italy for both male and female workers. The same effect concerns part-timers in the central Italian regions, mainly for male workers after 2011, but also for females in 2018. Instead, municipality size has no significant effect on the dependent variable.

Furthermore, the heterogenous effects on IPT working status by worker’s gender highlight further noteworthy considerations.

First, several drivers of IPT working status are mostly only related to women, while they are generally non-significant for male workers. In particular, marital status, partner’s occupational status and the number of children in the household (especially more than two) rarely influence in statistically significant terms the dependent variable for male workers.Footnote 10 As these variables overall reduce the probability of IPT working status among female workers, our results underscore that women’s willingness to accept part-time employment (and female participation in the labour market generally) is still strongly linked to the presence/necessity of a partner in Italy, with few or no changes in the period analysed.

Second, male and female workers report opposite effects on IPT working status of the presence of a child in the household and of being married to an unemployed partner. Specifically, male workers tend to ‘suffer’ a part-time contract more if they have an unemployed partner (a significant coefficient for 2006) or a child (with respect to having no child, with significant coefficients for 2011 and 2018), whereas the same situation often engenders a lower probability of females being hired involuntarily as part-timers.

The covariates related to individuals’ occupations of Model 2 presented in Table 4 reveal interesting drivers jointly shared by female and male part-timers. An additional year spent in the same firm reduces the probability of IPT working status by approximately 1% regardless the gender. Similarly, being a fixed-term or atypical part-timer is associated with a higher probability of being in IPT employment compared to those with an open-ended contract, and this effect is constant both through the years and gender analysed. Furthermore, the sector of activity suggests that male workers are catching up with their female counterparts concerning the wide-spreading of the phenomenon analysed over time. While IPT in 2006 were mainly related to the Agricultural sector, during and after the great recession, the sector of activity is no longer relevant in explaining IPT working status among male workers in line with what is observed among female ones.

However, the results suggest that, apart from an extemporaneous positive effect related to public employment, the gender profile of IPT workers tends also to differentiate. A low level of skills steadily influences the status of IPT for women but not for men, characterised by the same effect only in 2018, indicating a further element of potential convergence. The estimated coefficients related to company size are quite unstable over time for women, indicating that they are related to the cyclical labour market evolution; on the contrary, for men, part-time involuntariness seems to be transversal to this aspect.

Finally, while characteristics influencing the probability of an IPT employment were quite different by gender in 2006, we observe an important gender-convergence on these drivers over time in the Italian labour market. Looking at the year 2018, female workers report relevant differences on estimated coefficients—with respect to male ones—as regard household characteristics (i.e. partner’s occupational status and number of children) only. This evidence seems to confirm that female workers still suffer cultural and social pressions related to their (expected) domestic and care duties. When covariates of Model 1 and Model 2 are included together in the model specification (Table 6 in the Appendix), this consideration overall holds, and additional significant differences furhter arise. Specifically, the attainment of a university degree (having the Italian citizenship) decreases (increases) the probability of IPT employment for female workers only.

5.3 Accounting for the Full-Time Employment: A Robustness Check

The socio-economic literature suggests that important differences among workers also arise on the probability of having a part-time employment (against having a full-time employment) regardless of whether it is involuntary (Borowczyk-Martins & Lalé, 2016). This evidence appears quite relevant especially when gender disparities represent the main focus (ibidem).

As stated in Sect. 4, we focus here just on the probability of being involuntary (vs voluntary) part-timers, and then on a sample of part-timers only. However, different characteristics and conditions leading toward a full-time employment rather than a part-time one may, to some extent, affect our main results. For this reason, as a robustness check, we present here the estimation results of multinomial Logit models where the dependent variable reports three outcomes, thus adding ‘full-time employment’ to the two ones analysed in the previous sections (i.e. voluntary vs involuntary part-time employment).

Tables 10 and 11 in the Appendix illustrate the marginal effects estimated through the multinomial models. Clearly, this robustness check seems to overall confirm that our main considerations hold when also accounting for the probability of having full-time employment among workers. Nonetheless, these further estimates provide new interesting insights to our main analysis. First, it appears that having one or more children within the household negatively influences the probability of being both voluntary and involuntary part-timers among male workers, especially in more recent years (Table 10). In contrast, coefficients related to the number of children within the household are not generally significant on the IPT status but strongly significant on the PT status for women. Similarly, having one household member with a disability appears to have no effect on the multinomial outcomes analysed for male workers, while it significantly influences PT employment (especially instead of the IPT employment) for women.

Holding a university degree seems to be an element of protection from IPT employment more for women than men, as well as being married (Table 10). The multinomial analysis also confirms the different influences related to living in an owned house, with female workers constantly presenting negative coefficients concerning IPT employment, whereas, among men, this effect is limited only to 2006. Interestingly, including full-time workers also reveals a further element of influence on IPT employment. Living in a metropolitan area, especially among male workers, is related to negative coefficients of being in full-time employment (except in 2011). Coefficients of territorial dummies detected through Probit models are also confirmed here, with workers living in the Italian Central and Southern regions more exposed to IPT employment regardless of the worker’s gender.

Besides confirming the positive effect of job relationship tenure, Table 11 further disentangles the influence related to skill levels. The low (and average) skills seem to influence female IPT employment more than male one. In particular, female workers with a low or average occupation skill level have a much lower probability of being employed with a full-time contract, especially in 2006 and 2018, while low-skilled male workers only tend to have a higher probability of dealing with an IPT status. To be noted, having a low/average occupation skill level started to positively influence with a larger extent the IPT rather than the PT status from 2011 onwards both female and male workers.

Finally, results presented in Table 11 indicate an interesting insight not detected through the Probit analysis. When compared with full-time employment and voluntary part-time occupation, company size influences IPT employment, but exclusively among male workers. Specifically, the larger the firms, the lower the probability of being in IPT occupations. This evidence indicates a further trait of IPT employment transversal to gender. After the great recession, IPT employment is mainly diffused in the services sectors (Production, Distribution, Personal and Social), with a similar trend by gender but with a higher magnitude for women.

6 Conclusions

IPT work is a phenomenon of growing importance, especially in countries like Italy and Spain, but it can severely affect the European labour market in the case of a long economic crisis.

This paper provides a deep analysis of characteristics that influences the IPT employment, focusing on both socio-demographic and job ones at the individual and household level, to understand how they differ by gender and changed over time after the exogenous economic shock related to the Great Recession.

The country-uniqueness of the information collected in the INAPP-PLUS survey and the emblematic importance of the case of Italian IPT work strengthen the significance of the results described in the paper and the relevance of analysing IPT work from a broader perspective.

The main outputs of the econometric analysis are in line with the literature on IPT work and reveals that the IPT status is related to the ‘degree of constraint’ that individual willingness in labour choices has to face, which depends on a combination of individual, household, and labour characteristics. Results of our research on the Italian case show that individual and household characteristics seem to prevail in explaining differences in the voluntariness of part-time status by worker’s gender. Indeed, the role of labour characteristics in influencing IPT working status is often similar between female and male workers. Specifically, our results show that women aged 36 or over (or less than 26), with a high education level, married with an employed partner, or with children or disabled members within the household face a low degree of constraint and tend to choose part-time jobs voluntarily. Conversely, male workers with only one child tend to suffer the IPT working status. Looking at how the characteristics influencing the IPT employment changed over time, our analysis highlights that an important gender-convergence is underway. While characteristics influencing the probability of IPT employment were quite different by gender in 2006, Italian female workers report relevant differences in estimated coefficients as regard household characteristics only in 2018. As regards the role of household characteristics on the IPT status, the multinomial regression analysis, which also considers the full-time condition as employment outcome, provides additional insights which better explain differences by worker’s gender. In fact, since 2011, we observe that potential family care tasks (i.e. presence of children or persons with disability within the household) negatively influence the probability of being part-timer in general among male workers, whereas they significantly influence the PT employment (mainly instead of the IPT employment) for women.

These considerations emphasise the importance of gender-role models in influencing the willingness of individuals in the labour market. In fact, women are more likely to choose part-time jobs because the preference for work-family reconciliation is not equal across genders. Indeed, when expectations of personal fulfilment attached to work are high as a response to cultural expectations and/or individual/household preferences, there is a greater risk of being forced into a part-time position (rather than choosing it). When personal fulfilment does not only depend on work outcomes, IPT work is instead less frequent.

The process of convergence between the gender profiles of IPT employment, drivers also by the diffusion of the phenomenon among male workers, seems to move different processes. IPT employment for women appears to originate from the joint pressures of the gendered division of domestic labour and limited bargaining power, particularly evident in the case of low-skilled workers. On the other hand, IPT employment among male workers seems to be driven mainly by the demand side, suggesting a further element of insecure employment. In other terms, the longitudinal perspective seems to suggest that while IPT employment has increasingly constituted an insecure occupation for both genders, female workers tend to be more exposed to it when their labour market profile is not able to counteract the “dead weight” related to the (unequal) gendered division of domestic labour and childbearing. On the contrary, among male workers, it seems to constitute a further “tool” for expanding occupation while reducing labour costs. Furthermore, the results of the gender and longitudinal analysis seem to suggest that IPT work has internal consistency, indicating that this kind of employment matters in the study of working behaviours and of the labour market in general.

In conclusion, considering the expected profound changes in working structure related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which will probably remain in the long run (Baert et al., 2020; Brynjolfsson et al., 2020), we believe that our results can inform policymaking on preventing a further expansion of IPT occupations, particularly in economic activity sectors more exposed to future changes.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article were provided by the Italian National Institute for the Analysis of Public Policies (INAPP) by permission. Data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author with permission of INAPP.

Notes

The IPT boost was one of the major negative side effects of the economic crisis in Italy (Fellini & Reyneri, 2019), with the total number of workers not decreasing in the period 2007–2018 while the total number of hours worked dropped despite workers’ desired working hours being (apparently) unchanged.

In this study, IPT workers are defined as reporting working less than 35 h a week with the involuntariness resulting from constraints originating on the demand side of the labour market. In particular, they are people who work part time because they were not able to “find full time work or because business is poor”.

The stratification of the INAPP-PLUS survey sample is based on population strata by NUTS-2 region of residence, degree of urbanisation (i.e. metropolitan or non-metropolitan area), age group, sex and employment status (i.e. employed, unemployed, student, retired or other inactive status). One of the key elements in this dataset is an absence of proxy interviews: in the survey only survey respondents are reported to reduce measurement errors and partial non-responses.

It should be noted that four further INAPP-PLUS waves are available for the years 2008, 2010, 2014, and 2016. Nonetheless, we decided to exclude them from our analysis because some variables are missing in the former two waves and for the sake of simplicity for the latter two ones. The 2008 wave does not provide the variable of the number of children in the household but just their presence (i.e. household with children or without). The 2010 wave, it does not provide the variable regarding marital status. However, making the necessary changes to the model specification, as a sensitivity analysis we replicated the econometric analysis on these two waves and the results overall confirm our main findings. More details are available on request.

In line with the literature on the involuntariness of part-time work, this question allows framing IPT work based on individual will. To be noted, the potential drawback of this methodological choice is that the answer to this question may be—to some extent—biased by the respondents' unsatisfaction about their working status. Given the potential reverse causality between these two dimensions and the absence of a longitudinal component, we cannot however investigate the extent of the mentioned measurement error.

Table 6 in the Appendix also provides econometric results for a further model specification (Model 3) considering together all characteristics included in Model 1 and Model 2. Results presented in Table 6 overall confirm what shown in the main analysis of this study. However, we prefer providing results of Model 3 in the Appendix only because they may suffer potential endogeneity bias as job characteristics are strongly related to the characteristics of the profession of the part-time employment.

For the sake of clarity, Table 7 in the Appendix provides results of our main analysis for the full sample of Italian workers.

Since the part-time status of the work relationship is self-declared in the INAPP-PLUS survey, as a sensitivity analysis we tried to reproduce our main analysis on a sample of part-timers with the maximum number of working hours a week being restricted to 35. The results of this sensitivity analysis, shown in the Appendix (Table 9), overall confirm the robustness of our main findings.

Note that the scarce statistical significance of coefficients in the estimates for males might be related in this case to the small number of observations.

References

Anxo, D., Fagan, C., Smith, M., Letablier, M. T., & Perraudin, C. (2007). Part-time work in European companies: Establishment survey on working time 2004–2005. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Atkinson, J. (1984). Manpower strategies for flexible organisations. Personnel Management, 16, 28–31.

Baert S., Lippens L., Moens E., Sterkens P., & Weytjens J. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis and telework: A research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes. GLO Discussion Paper, 532.

Barbieri, P. (2011). Italy: No country for young men (and women): The Italian way of coping with increasing demands for labour market flexibility and rising welfare problems. In H. P. Blossfeld, S. Buchholz, D. Hofäcker, & K. Kolb (Eds.), Globalized labour markets and social inequality in Europe (pp. 108–145). Palgrave Macmillan.

Barbieri, P., Cutuli, G., Guetto, R., & Scherer, S. (2019). Part-time employment as a way to increase women’s employment: (Where) does it work? International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 60(4), 249–268.

Belfield, C., Blundell, R., Cribb, J., Hood, A., & Joyce, R. (2017). Two decades of income inequality in Britain: The role of wages, household earnings and redistribution. Economica, 84(334), 157–179.

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Hakim, C. (1997). Between equalization and marginalization: Women working part-time in Europe. Oxford University Press.

Bonacini, L., Gallo, G., & Scicchitano, S. (2021). Working from home and income inequality: Risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19. Journal of Population Economics, 34(1), 303–360.

Borowczyk-Martins D., & Lalé E. (2016). How bad is involuntary part-time work?. IZA discussion paper series, 9775.

Brynjolfsson E., Horton J., Ozimek A., Rock D., Sharma G., Yi, Tu., & Ye, H. (2020). Covid-19 and remote work: An early look at U.S. data. NBER Working Paper, p. 27344.

Clementi, F., & Giammatteo, M. (2014). The labour market and the distribution of earnings: An empirical analysis for Italy. International Review of Applied Economics, 28(2), 154–180.

Dotti Sani, G. M. (2015). Within-couple inequality in earnings and the relative motherhood penalty. A cross-national study of European countries. European Sociological Review, 31(6), 667–682.

Dotti Sani, G. M., & Luppi, M. (2021). Absence from work after the birth of the first child and mothers’ retirement incomes: A comparative analysis of 10 European countries. Work, Employment and Society, 35(3), 470–489.

European Commission (2014). Employment and social developments in Europe 2014. Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, European Commission.

Fellini I., Reyneri E. (2018). Intensità del lavoro, evoluzione dell’occupazione, polarizzazione, in CNEL (Ed.), XX Rapporto mercato del lavoro e contrattazione collettiva 2017–2018, CNEL.

Fellini I., Reyneri E. (2019). Intensità del lavoro, evoluzione dell’occupazione, polarizzazione, in CNEL (Ed.), XXI Rapporto mercato del lavoro e contrattazione collettiva 2018–2019, CNEL.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The “southern model” of welfare in social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 6(1), 17–37.

Filandri, M., & Struffolino, E. (2019). Individual and household in-work poverty in Europe: Understanding the role of labor market characteristics. European Societies, 21(1), 130–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1536800

Filippetti, A., Guy, F., & Iammarino, S. (2019). Regional disparities in the effect of training on employment. Regional Studies, 53(2), 217–230.

Gardiner, L., & Gregg, P. (2017). Study, work, progress, repeat? How and why pay and progression outcomes have differed across cohorts. Resolution Foundation.

Ice, L., Rieley, M. J., & Rinde, S. (2021). Employment projections in a pandemic environment, in Monthly Labor Review. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2021.

Kauhanen, M., & Jouko, N. (2015). Involuntary temporary and part-time work, job quality, and well-being at work. Social Indicators Research, 120(3), 783–799.

Leschke, J. (2013). Has the economic crisis contributed to more segmentation in the labour market and welfare outcomes? An analysis of EU countries (2008–2010). Revue Française Des Affaires Sociales, 4, 1–19.

Lyonette, C. (2015). Part-time work, work–life balance and gender equality. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 37(3), 321–333.

Lyonette, C., Baldauf, B., & Behle, H. (2010). Quality part-time work: A review of the evidence. Government Equalities Office.

Nicolaisen, H., Hanne, C. K., & Ragnhild, S. J. (2019). Introduction. In H. Nicolaisen, C. K. Hanne, & S. Ragnhild (Eds.), Dualization of part-time work (pp. 1–31). Policy Press, Bristol University Press.

Nightingale, O. (2018). Looking beyond average earnings: Why are male and female part-time employees in the UK more likely to be low paid than their full-time counterparts? Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), 131–148.

O’Dorchai, S., Plasman, R., & Rycx, F. (2007). The part-time wage penalty in European countries: How large is it for men? International Journal of Manpower, 28(7), 571–603.

O’Reilly, J., & Fagan, C. (1998). Part-time prospects: An international comparison of part-time work in Europe, North America and the Pacific Rim. Routledge.

OECD (2010). OECD employment outlook 2010. Moving beyond the job crisis. OECD.

Rosenfeld, R. A., & Birkelund, G. E. (1995). Women’s part-time work: A cross-national comparison. European Sociological Review, 11, 111–134.

Rubin, J., Rendall, M. S., Rabinovich, L., Tsang, F., Van Oranje-Nassau, C., & Janta, B. (2008). Migrant women in the European labour force: Current situation and future prospects. RAND Europe.

Saraceno, C., & Keck, W. (2010). Can we identify intergenerational policy regimes in Europe? European Societies, 12(5), 675–696.

Tijdens, K. G. (2002). Gender roles and labor use strategies: Women’s part-time work in the European Union. Feminist Economics, 8(1), 71–99.

Tilly, C. (1996). Half a job: Bad and good part-time jobs in a changing labor market. Temple University Press.

Valletta, R.G., & van der List C. (2015). Involuntary part-time work: Here to stay?, FRBSF Economic Letter, 19.

Valletta, R. G., Bengali, L., & Van der List, C. (2020). Cyclical and market determinants of involuntary part-time employment. Journal of Labor Economics, 38(1), 67–93.

Warren, T., & Lyonette, C. (2018). Good, bad and very bad part-time jobs for women? Re-examining the importance of occupational class for job quality since the ‘great recession’ in Britain. Work, Employment and Society, 32(4), 747–767.

Webber, G., & Williams, C. (2008). Mothers in “good” and “bad” part-time jobs: Different problems, same results. Gender & Society, 22, 752–777.

Wielers, R., Münderlein, M., & Koster, F. (2014). Part-time work and work hour preferences. An International Comparison. European Sociological Review, 30(1), 76–89.

Funding

Open access funding provided by European University Institute - Fiesole within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11.

Part-time employment as share of total employment by gender and country. EU stands here for the 19-country eurozone, which consists of Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. Total employment refers to the population aged 15–64.

Involuntary part-time employment as share of part-time employment by country. EU stands here for the 19-country eurozone, which consists of Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain. Part-time employment refers to the population aged 15–64.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Busilacchi, G., Gallo, G. & Luppi, M. I Would Like to but I Cannot: What Influences the Involuntariness of Part-Time Employment in Italy. Soc Indic Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03339-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03339-2