Abstract

The Human Development Index (HDI) produced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has been in existence since 1990. In its annual Human Development Reports (HDRs) the UNDP provides rankings of countries based on the HDI, and the idea is that these will help bring about positive change as countries compare their performance in the rankings with what they see as their peers. The HDRs are widely reported in the media, and previous research has suggested that the extent of newspaper reporting of the HDI (i.e. number of articles) is greater for those countries at the bottom and top end of the rankings. However, there are gaps in knowledge about how the HDI is reported in these media outlets. For example, to what extent does newspaper reporting of the HDI equate it to terms such as ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’, and how does this relate to the ranking of countries based on the HDI? This is the question addressed by the research reported in this paper. Results suggest that newspaper do often associate the terms ‘quality of life and ‘well-being’ with the HDI, and that the association appears to be stronger for countries towards the top-end of the rankings (i.e. those that have more ‘human development’) compared to those at the bottom-end of the rankings. This suggests that the association between reporting of the HDI and ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ is a narrative that is perceived by the media to suit the developed rather than developing world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Human Development Index (HDI) was developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and it is often claimed that the motive behind its creation was a desire to move the development discourse away from economics and towards a more balanced vision of ‘human development’ (Anand & Sen, 1994; Kelly, 1991; Moldan, 1997; Ogwang, 2000; Sagar & Najam, 1998). The HDI was designed as an index to capture the vision of human development espoused by the UNDP and was intended to be for human development what GDP/capita and related indicators are for economic development (Oulton, 2012). The use of a single index to ‘capture’ human development has the advantage of allowing for a ranking of countries in a ‘league table’ format, with best performers at the top and worst at the bottom. This device allows countries to compare their performance in human development against those they consider to be their peer group (Ogwang, 2000), and the table typically appears first amongst many other tables of indicators at the end of the Human Development Reports (HDRs) published by the UNDP (Böhringer & Jochem, 2007; Wilson et al., 2007). One of the interesting aspects to the HDI is how it is interpreted. The definition of human development provided by the UNDP is centred on a “process of enlarging people’s choices”, and the HDI was designed to capture the three foundation stones (health, education and income) upon which these choices are founded. However, there are similarities here with other terms such as quality of life and well-being. Indeed, the HDRs, especially from 2010 onwards (2010 being the 20th anniversary of the launch of the first HDR), make a strong association between human development and well-being although the link between the two is not always clear. The following quotes from HDR 2010 provide examples (emphases are those of the author):

“The 1990 HDR began with a clear definition of human development as a process of “enlarging people’s choices,” emphasizing the freedom to be healthy, to be educated and to enjoy a decent standard of living. But it also stressed that human development and wellbeing went far beyond these dimensions to encompass a much broader range of capabilities, including political freedoms, human rights and, echoing Adam Smith, “the ability to go about without shame.” (HDR 2010; page 2).

“The central contention of the human development approach, by contrast, is that wellbeing is about much more than money: it is about the possibilities that people have to fulfil the life plans they have reason to choose and pursue.” (UNDP HDR, 2010; page 9).

The first of these would appear to suggest that human development is related to but different from well-being while the second appears to suggest that the two are interwoven. While not wishing here to delve into all the intricacies of these debates in the academic literature, Jayawickreme et al. (2012) have provided an intriguing analysis of the relationship between human development and well-being. They refer to human development as espoused by the UNDP, with the HDI being a reflection of that, as an example of a ‘needs-based’ theory to well-being in that the emphasis is upon identifying and cataloguing goods required for ‘well-being’ and a ‘happy life’. While Jayawickreme et al. (2012) acknowledge that such a ‘needs based’ theory does not necessarily discount what people may want or like to have, it does place a vision of ‘need’ at the heart of well-being and the HDI is a practical reflection of that emphasis created. In effect the HDI comprises an assessment of the ‘inputs’ (health, education, income) required to achieve well-being rather than being an index of well-being per se. The assumption is that having those ‘inputs’ in place would help create ‘well-being’ almost as an output. As Jayawickreme et al. (2012) have noted:

“[The HDI] lacks psychological variables and we maintain that variables other than life expectancy and education are important for well-being. From a psychological perspective, we recommend that measures of personality, strengths, talents, and values of a nation (or an individual) should be used to index positive or negative changes in endogenous inputs.”

While these arguments about the nexus between well-being, quality of life and human development have been well-covered within the academic literature a question can be asked about how others outside of the research community have interpreted the HDI? This matters as the HDI, along with the country rankings based upon it, have been designed primarily as a device for the promotion of the UNDP’s vision of human development, and its assessment of the ‘state of play’ of countries as seen through that lens, to a diverse range of stakeholders, including politicians, policy makers, leaders in the private/public/third sectors, the media and the public. The HDI and the rankings of countries based upon it were created primarily as devices to help bring about positive change; or perhaps more accurately, what the UNDP regards as positive change as seen through the lens of the HDI. Like all indices, it is fundamentally a communication tool, and its success can only be judged in terms of whether it has impact such as raising awareness of the UNDP’s vision of human development and bringing about positive change in the lives of people. Hence the intended ‘consumers’ of the HDI rankings represents a very diverse group, and this includes the media. However, the media reporting of indices and indeed how this could influence interventions by governments and others remains a relatively under-explored field of study. For example, one of the few empirical studies to explore the influence of index-based country rankings on government policy is that provided by Doshi et al. (2019) for the Ease of Doing Business (EDB) Index.

While the media reporting of the HDI remains a relatively unexplored field, there has been some research on how newspapers, as one subset of the media, have reported the HDI as well as factors that may influence the extent of reporting. For example, Morse (2011a, b, 2013) has explored various aspects of the reporting of three indices, one of which was the HDI, in the UK national press between January 1990 and December 2009. Reporting of the indices was assessed by the number of newspaper articles published each year mentioning the index at least once, and results showed that all three indices had an increasing presence in the press since the 1990s. This author also noted how the HDI was sometimes associated with the notion of ‘quality of life’ in some of the articles and how it was often used as an authoritative (i.e. the HDI was produced by a highly-respected body – the UNDP) device to provide support to wider discussions of development, aid, conflict etc. Morse (2016) assessed the newspaper reporting of 24 indices, including the HDI, up to 2012, and showed how various factors could influence the extent of reporting such as the length of time the index had been in existence as well as its focus. Indeed, Morse (2014, 2018) noted how countries at the top and bottom ends of the HDI rankings attract more press attention compared to those towards the middle of the tables, and also how changes in the methodology of the HDI can generate significant changes in country rank which itself can result in more press attention. Morse (2018) has noted how the media emphasis on countries at the top and bottom ends of the HDI rankings chimed with the ‘extremity hypothesis’ formulated by Heath (1996) which assumes that people are more likely to transmit information regarding what they regard as the extremes of ‘good’ or ‘bad’; perhaps because people value ‘sensationalism’ and ‘surprisingness’ or think that others do so. Hence countries ranked at the top of the HDI tables equate to ‘good news’ stories while those towards the bottom end of the table equate to ‘bad news’ stories. However, in all these analyses much can presumably depend on how ‘media reporting’ is assessed. In the examples above this was achieved by simply counting the number of newspaper articles that mentioned the HDI at least once, but this approach did not take into account the length of the articles (e.g. number of words published).

Nonetheless, given the points made above about the HDI being a measure of needs (or inputs) for the achievement of well-being rather than being an index of well-being per se, a reasonable question to ask is whether the media use the HDI as a representation of well-being and quality of life? This is a complex question to unpack, but a starting point would be to explore the extent to which the HDI and ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ are associated within the media; how often do the terms appear together? It could reasonably be hypothesised that the use of these terms in the media may reflect their use in the HDRs as, after all, it is these reports that are the main vehicle for dissemination of the HDI and what it represents by the UNDP. It is these questions that were at the heart of the research reported here.

The paper begins by setting out the methodology used in the study, and this section includes a brief background to the HDRs, how the UNDPs vision of ‘human development’ relates to other published definitions of Quality of Life and well-being, and the structure and assumptions behind the HDI. The methodology section also sets out how the data were collated for a sample of 135 countries and the nature of the statistical analysis that was employed. The results section is in three main parts. Firstly, the section presents the results of analysis of the frequency of use of the terms Quality of Life and well-being in the HDRs published between 1991 and 2022. Secondly, the results present an analysis of newspaper reporting of the HDI from 1991 to 2022 across the sample of 135 countries for which published values of the HDI, and rankings based on them, are available. Finally, the section presents results from an analysis of the frequency of the terms ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Wellbeing’ used in newspaper articles that have reported the HDI. The paper ends with a discussion of the results and sets out some conclusions and suggestions for further research.

2 Methodology

2.1 Human Development Index: A Brief Background

The state of human development across the world has been set out since 1990 in the HDRs published, mostly annually, by the UNDP, and included within these reports is a ranking of countries based on their values of the HDI. Table 1 lists the years of publication, the theme of each HDR and the number of countries included in the HDI ranking. The HDR was not published for some years (2012 and 2017) and just one combined report was published for the periods of 2007/08 and 2021/22. In its very first HDR the UNDP provided a definition of human development, and this has been set out in Table 2 alongside some published definitions of Quality of Life and well-being from a variety of sources. The examples provided in Table 2 are by no means exclusive or necessarily the most widely adopted, but it can be seen that there are overlaps with human development.

The UNDP’s vision of human development drew heavily from the work of a Nobel Prize winner in economics, Amatyra Sen, who explored the importance of ‘capabilities’ in development (Anand & Sen, 1994; Sen, 1999). Since its inception in 1990 the HDI has comprised the following three elements (Anand & Sen, 1994; Cherchye et al., 2008):

-

1.

Life Expectancy. Included as a proxy measure for health and it is assumed in broad terms that the higher the life expectancy then the better the level of health in a country (Riley, 2005). The basis for including this component is that people cannot improve their livelihood unless they are healthy.

-

2.

Education. It is assumed here that with more education people can have more income and can also make better use of the income they have.

-

3.

Income. It is assumed that people need financial capital to help improve their livelihood options through the purchase of goods and services.

All three have consistency been allocated an equal ‘weighting’ in the HDI, although this decision has been questioned by many researchers (Lind, 2010; Blancard & Hoarau, 2011; Ravallion, 2012; Tofallis, 2013; Pinar et al., 2017). In the view of the UNDP, economics should be treated as part of the foundation needed to provide essential choices rather than being the sole concern (Anand & Ravallion, 1993; Aturupane et al., 1994; Cilingirturk & Kocak, 2018; Streeten, 1994). Hence the HDRs often carry numerous expressions along the lines of the following:

“According to this concept of human development, income is clearly only one option that people would like to have, albeit an important one. But it is not the sum total of their lives. Development must, therefore, be more than just the expansion of income and wealth. Its focus must be people.” (UNDP HDR, 1990; page 10).

However, the inclusion of just three components to span ‘capability’ has been criticised and Nussbaum (2011), for example, suggests that 10 ‘core’ capabilities are important in human development, including being able to laugh and play. There have also been many calls for the UNDP to encompass wider ‘sustainability’ dimensions within the HDI such as the environment (Bravo, 2014; Hickel, 2020; Morse, 2004; Neumayer, 2001, 2012; Sagar & Najam, 1998), flows rather than stocks (Hou et al., 2015), the use of thermodynamic optimisation approach (Umberto & Giulia., 2021), the relative efficiency of converting commodities to capabilities (Assa, 2021) and ‘human values’ (proxied by an index of corruption; Sharma & Sharma, 2015). Some have even called for a replacement of the HDI by another index (Hou et al., 2015). But one of the key concerns of the UNDP has been a desire to keep the HDI as simple and as straightforward as possible (Carlucci & Pisani, 1995; Booysen, 2002; Ranis et al., 2006; Stapleton & Garrod, 2007; Nguefack‐Tsague et al., 2011). An index of human development based on the core capabilities set out by Nussbaum (2011), for example, would be highly complex. Hence to date none of these have been adopted by the UNDP within a revised HDI. Indeed, the UNDP have consistently rejected any change to the HDI, and it has remained as an index that aims to measure some of the ‘needs’ required for well-being rather than being a measure of the ‘well-being’ of a nation.

2.2 Sample of Countries and Calculating Adjusted Rank

While a ranking of countries using the HDI was first published in the HDR of 1990 this was in many ways a pilot study that only included 130 countries. Hence the focus here is upon the HDI published in the HDRs between 1991 and 2021/2022 (Table 1) although there were two years (2012 and 2017) where no HDRs were published, and two occasions where years were combined into one report: 2007/2008 and 2021/2022. However, there have been many changes in the countries included in the HDI rankings over those years as some have disintegrated into smaller states (e.g. USSR) and others are missing for some years because of war and natural disasters. Hence it was necessary to select only those countries which had appeared in all the HDI rankings between 1991 and 2022, and the list of countries included in the analysis are shown in Table 3. Each of the 135 countries in Table 3 has a total of 28 published rankings based on the HDI.

One of the challenges of analysing changes in country rank based on the HDI is that the number of countries included in the published rankings varies over time (Table 1). Hence a country could easily find itself moving up or down a ranking from one year to the next because of the addition or removal of countries. For example, Niger was ranked at 187 in the HDR of 2014, 188 in HDR 2015 and 189 in HDR 2018, 2019 and 2020. In all these published tables Niger was the bottom-ranked country, so the ranks of 187, 188 and 189 spanning these years are simply a reflection of changes in the number of countries included in the table. Therefore, some allowance needs to be made for changes in the number of countries in the HDI tables by calculating an adjusted rank for each of them. The published rankings were transformed to a fixed scale (adjusted rank) so that 1 is given to the top-ranked country and 2 is given to the bottom-ranked country. That way, even if the published rankings fluctuated the country that appeared at the bottom of the table would still have a value of 2. This can be readily achieved using the original (published) rank of a country in the tables as follows:

This adjustment was made to the rank of all countries in the published table prior to the selection of the samples for the indices. As noted above, there are many criticisms of the HDI in the literature but for this research the focus was upon the ‘headline’ country rankings as published in the HDRs as these are the rankings that were distributed by the UNDP to the media and other stakeholders. It should also be noted that the retrospective rankings of the HDI that have often appeared in the HDRs, especially following a change in index methodology, were not included.

2.2.1 Frequency of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Well-Being’ in the Human Development Reports and Newspaper Articles

For the HDRs, the total number of words in each of them (1991 to 2021/22) was assessed along with the number of mentions of the terms ‘Quality of Life’ and two variants (hyphenated and non-hyphenated) of well-being. Frequency of mentions of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Well-being’ were assessed by dividing the number of mentions of the terms in the HDR by the word count for the HDR.

For newspapers, there are various approaches that could be used to assess the extent of coverage of the HDI, and the following three were employed here for each of the countries in the sample:

-

(a)

Number of articles that mention the HDI at least once.

-

(b)

Length of the articles (i.e. their word count) found under (a).

-

(c)

Average length of the articles (i.e. b divided by a).

These metrics do represent a relatively simple means for the assessment of newspaper reporting of the HDI for each country between 1991 and 2022 and they can be readily gleaned using software and access to an historical and global database of newspaper articles. For the research reported here the analysis was undertaken using the Nexis database (www.lexisnexis.com/en-us/professional/nexis/nexis.page). The search was restricted to newspapers (all languages) and the custom search dates were from 01/01/1991 to 31/12/2022.

The first of these metrics (number of newspaper articles) has been employed in many of the published papers to date (e.g. Morse, 2011a, b), and is an aggregate figure derived by summing the number of newspaper articles that mention the HDI and respective country at least once that were published between the years 1991 and 2022. For example, for Albania (the first country listed in Table 3) the total number of newspaper articles published between 1991 and 2022 (a total of 32 years) that mentioned the HDI and Albania at least once was 39. But just using an aggregate value for number of newspaper articles does not take into account the length (i.e. number of words) of those articles. An article that is, in essence, a brief report of the HDI rankings for that year, comprising perhaps a paragraph, is counted the same as a more in-depth article. Hence the second approach (word count of the articles) was also included. For Albania, the total number of words in the 39 newspaper articles that mention the HDI and that country at least once was 46,897. This yields an average article word count of 46,897/39 = 1,202. It does need to be noted here that those articles may well mention other countries besides Albania. Also, it is often the situation that the same article would be published in various publications, and in that case they were counted as separate articles.

Newspaper articles that mentioned the HDI at least once were also searched for mentions of ‘Quality of Life’ and the two variants (hyphenated and non-hyphenated) of ‘well-being’. The frequency of mentions of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘well-being’ were assessed by dividing the counts of the terms by the total number of words in the newspaper articles. For example, in the case of Albania there were 9 and 10 mentions respectively of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Well-being/wellbeing’ in newspaper articles published between 1991 and 2022. As the total word count of all the newspaper articles for this country was 46,897, these equate to a frequency of 0.1919 and 0.2132 mentions of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Well-being/wellbeing’ per 1,000 published words. However, it does need to be stressed that the conceptualisation and thus meaning of ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ are unlikely to be consistent across journalists, and indeed the readers of the articles. Hence the counts given here are for the use of the terms by journalists and no accommodation has been made to allow for any diversity in conceptualisation amongst them.

2.3 Data Analysis

Data analysis was mostly undertaken using least squares regression, with the independent variable being the mean adjusted rank of the HDI for each country in the sample. The mean adjusted rank for each country in the sample was used as the rank of most countries does not change that much over the 28 HDRs. The use of a least squares regression approach allows for the fitting of some simple models and thus the identification of patterns across the mean adjusted ranks of countries. A number of dependent variables for each country were used in the regressions. As noted above, the first group of these (total number of articles, total number of words for those articles and mean article length) were used to Assessed newspaper coverage of the HDI for each of the countries in the sample. The other two dependent variables for each country in the sample were:

-

The frequency of mentioning the term ‘Quality of life’ in articles that mention the HDI at least once.

-

The frequency of mentioning the term ‘Well-being’ (and ‘wellbeing’) in articles that mention the HDI at least once.

In both these metrics, frequency was expressed in terms of mentions of Quality of Life and well-being per 1,000 published words in the newspaper articles.

As the values for the three variables used to assess newspaper coverage can be very large, and there can be outliers, it was decided to take a logarithmic transformation. In each case the transformation was made as follows:

Z is the transformed value while x is the original value.

In terms of the choice of model, two were used here (where X is the mean adjusted rank for the countries in the sample):

The inclusion of the quadratic model was to test whether the dependent variables tended to be higher/lower for countries at the extremes of the rankings (top and bottom of the tables) relative to those countries towards the middle.

3 Results

3.1 Human Development Reports, Quality of Life and Well-Being

The length of the HDRs in terms of word count is summarised as Fig. 1a. The word count of the HDRs has fluctuated over time, but there was a marked increase as of HDR 2000; the HDR that marked the 10th anniversary since the first HDR published in 1990. The number of words and frequency of mention of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Well-being’ in the HDRs are presented in Fig. 1b and c respectively. ‘Quality of Life’ is a term not used all that much in the HDRs, but ‘well-being’ is much more prominent. The frequency of mention of well-being (mentions/1000 words) is shown as Fig. 1c. While the term has appeared in all the HDRs since 1990, there was a marked increase in its frequency of use since the HDR of 2010. The latter report represented the 20th anniversary since the publication of the first HDR in 1990 and was entitled ‘The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development’. Indeed, the period around 2010 witnessed something of a surge in the ‘Beyond GDP’ debate sparked by a number of agencies.

a Word count for each of the published human Development Reports (HDR) b Number of times the phrases ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Well-being’ are mentioned in the HDRs published since 1990. b Frequency (number of mentions per 1000 words) of mentioning the term ‘well-being’ in the HDRs published since 1990. Note: Searches were made for both hyphenated and non-hyphenated variants of ‘well-being’

3.2 Adjusted Ranks of Countries

Figure 2 is a plot of the standard deviation in adjusted rank for each country in the sample of 135 against the mean adjusted rank for that country. The standard deviation and mean adjusted ranks for each country was based on 28 published rankings of the HDI. The standard deviation does have a statistically significant (P < 0.001) relationship with the mean, with the ‘best fit’ (least-squares) model being quadratic in nature. The standard deviations tend to be higher for countries ranked towards the middle of the HDI tables, and lower for countries at the top and bottom of the tables. This suggests that countries towards the top and bottom-end of the rankings tend to be relatively stable in terms of their ranks; they stay in more or less the same place. Countries towards the middle of the HDI rankings have greater volatility in rank. However, the coefficient of variation (standard deviation as a percentage of the mean) of the adjusted rank for these countries is low (average of 3%) suggesting that there is relatively little volatility across all the rankings. Hence, the mean adjusted rank of each country could be used as a reasonable measure of ‘location’ for the period 1991 to 2022.

The line represents the least-squares regression equation (quadratic) of the form: St Dev adjusted rank = −0.3132 + 0.4974 Mean adjusted rank—0.1661 Mean adjusted rank.2 The sample of countries used for the analysis is presented as Table 3.

Term | Coefficient | SE | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|

Constant | −0.3132 | 0.0457 | −6.86*** |

Mean adjusted rank | 0.4974 | 0.0631 | 7.88*** |

Mean adjusted rank2 | −0.1661 | 0.0211 | −7.89*** |

The time period for the calculation of the mean and standard deviation was the Human Development Report of 1991 to that of 2021/22 as summarised in Table 1. The number of published HDI tables used to calculate the adjusted ranks was 28 .

3.3 Newspaper Reporting of the HDI

The total number of articles that mention the HDI at least once for all of the 135 countries in the sample between January 1991 and December 2022 are shown plotted as Fig. 3. The numbers are relatively low from 1991 to 2006 but show an increase as of 2007 and that is especially marked from 2009.

Figure 4 comprises three graphs which plot different aspects of newspaper reporting of the HDI against the mean adjusted rank for each country. The three aspects are total number of articles published that mention the HDI at least once (Fig. 4a), the total word count of all those articles (Fig. 4b) and the average word count per article (Fig. 4c). In all three cases, the dependent variable is the logarithm of the article and word counts. Also shown in these graphs are the best-fit quadratic regression models, and the details of these are shown in Table 4a, b and c. Table 4 comprises results for the raw and transformed (logarithmic) count data, and two regression models (linear and quadratic). Based on the transformed count data, the quadratic regressions for number of articles and number of words were statistically significant at P < 0.001 (adjusted R2 of 19.17% and 14.97% respectively), while for average word/article the statistical significance was P < 0.01 (adjusted R2 = 7.86%). None of the linear models were statistically significant at P < 0.05. These results suggest that for the number of articles and total word count, the figures were higher for those countries towards the top and bottom end of the HDI rankings. This is in agreement with the ‘extremity hypothesis’ of Heath (1996) that media interest would tend to be greater at the extremes of good and bad news. However, in terms of the average word count per article the situation is reversed, with the average lengths of articles being lower for those countries at the top and bottom end of the rankings. It is the articles towards the middle of the rankings that tend to have higher article lengths.

Number of newspaper articles a, number of words in the newspaper articles b and average newspaper article length c as a function of mean adjusted rank for countries in tables based on the Human Development Index. Lines are the ‘best fit’ (least squares) regression models shown in Table 4

3.4 Frequency of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Wellbeing’ in Newspaper Articles on the HDI

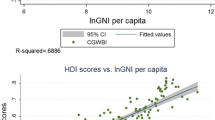

Figure 5a and b present the frequency (per 1000 words) at which the terms ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ are mentioned in newspaper articles that mention the HDI at least once as a function of mean adjusted rank for countries. The lines in these graphs are the ‘best fit’ (least squares) regression models (linear and quadratic), the details of which are presented in Table 5a and b. The picture is a complex one and suggests that the relationship between frequency of mention of ‘Quality of Life’ and average adjusted rank can be described in terms of both a quadratic (P < 0.001; adjusted R2 = 45.47%) and linear model (P < 0.001; R2 = 34.29%). Taking these models together, this picture suggests that the frequency for ‘Quality of Life’ tends to be higher for countries at the top and bottom end of the HDI rankings (quadratic model), but with the frequency being higher at the top relative to the bottom end (linear model). For the frequency of ‘well-being’ the pattern is somewhat simpler, with the linear regression model being the only one that is statistically significant (P < 0.001; R2 = 20.86%), and this suggests a greater frequency of mentioning ‘well-being’ for those countries towards the top end of the rankings relative to those at the bottom end of the rankings.

Frequency of mention (per 1000 words) of quality of life a and wellbeing b in newspaper articles as a function of mean adjusted rank for countries in tables based on the Human Development Index. Lines are the ‘best fit’ (least squares) regression models shown in Table 5. Note: Searches were made for both hyphenated and non-hyphenated variants of ‘well-being’

4 Discussion

The results point to a number of intriguing conclusions. Firstly, the extent of reporting of the HDI by newspapers does seem to have a relationship with the mean adjusted HDI rank of countries, although the nature of this relationship does depend on the measure of reporting used. If based on the number of newspaper articles and the total number of words across those articles then the relationship has a quadratic (‘U’) shape as shown in Fig. 4a and b, with a greater extent of reporting for those countries at the top and bottom end of the HDI rankings compared to those countries that are ranked towards the middle. However, there is no suggestion from Fig. 4a and b that the reporting metrics are higher for those at the top of the rankings relative to those at the bottom. This finding matches that of Morse (2014, 2018), and provides further support for the theory put forward by Heath (1996) that the ‘extremes’ of good and bad tend to attract most attention from the media. Indeed, the notion that the media often portrays a so-called ‘negativity’ bias has long been established (Boydstun et al., 2018; Garz, 2014; Haskins & Miller, 1984; Kätsyri et al., 2016; Kollmeyer, 2004; Soroka, 2006). Aday (2010; page 146) has commented:

“Indeed, one reason for the persistence of a negativity bias across news genres can be traced to the fact that conflict is what Herbert Gans (1980) found to be a fundamental news norm, something that journalists look for in defining a story as newsworthy. ‘‘Good news’’ is generally seen as less interesting to viewers than ‘‘bad news,’’ especially on television.”

Soroka (2006) has suggested that ‘Prospect Theory’ may play a role here as people tend to care more about losses than gains of an equal magnitude and as a result:

“Journalists will thus regard negative information as more important, not just based on their own (asymmetric) interests, but also on the (asymmetric) interests of their news-consuming audience. Observed trends in media content are, in this view, a product of asymmetric reactions to information at the individual level.” (Soroka, 2006; page 374).

Sensationalism, magnifying negative and positive aspects of a story, can sell more copies of newspapers and attract more listeners and viewers for the broadcast media (McCluskey et al., 2016). But there is also evidence there can be more nuance here and the media can also have a positivity bias for some information. For example, Lott and Hassett (2014) found a positivity bias when it came to reporting changes in GDP and a negativity bias when it came to reporting unemployment.

However, while the ‘U’ shape relationship between newspaper reporting of the HDI and mean rank of the HDI holds for two of the measures of reporting (number of articles and number of words) it does not hold when the mean article size (mean number of words per article) is used (Fig. 4c). Here the ‘best fit’ model is also quadratic in nature but in this case the model suggests that countries ranked towards the top and bottom of the HDI tables tend to have smaller average article lengths compared to those towards the middle of the rankings. There are various potential explanations for this. For example, as the countries in the middle of the rankings also tend to have greater variability in rank it is possible that the longer articles are linked to that variability, with journalists perhaps analysing the changes and the reasons behind them. Alternatively, it may well be that at the extremes of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ there is a tendency to report the fact rather than dissect it. This is certainly an area that warrants more research.

A second conclusion relates to the use of the terms ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ in both the HDRs and in newspaper reporting of the HDI. The term ‘Quality of Life’ hardly features in the HDRs; it is mentioned but typically less than 10 times per HDR for all the published HDRs. ‘Well-being’ is a term much more often used in the HDRs than ‘Quality of Life’, especially from 2010 onwards. The 2010 HDR marked the 20th anniversary of the first HDR published in 1990 and it is replete with discussion of the meaning of human development and how it differs from a narrower focus on economic development. It is perhaps no coincidence that 2010 is just a few years after the 2007 conference entitled ‘Beyond GDP’ hosted by the European Commission, the European Parliament, Club of Rome, OECD and WWF, and the 2009 communication of the European Commission entitled ‘GDP and beyond Measuring progress in a changing world’. HDR 2010 was published just after the economic crash of 2009, and in those post-crash years there did seem to be much interest in non-monetary based growth.

In terms of newspaper reporting of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Well-being’ in newspaper articles that mention the HDI at least once, there does seem to be a wide use of both these terms. There is no space here to provide all the context for their usage within the articles, but the following are a few examples:

“The ratings, known as the human development index, rank countries not by their wealth, but by the quality of life average Citizens face.” St. Petersburg Times (Florida) April 23, 1992.

“Human Development Index is a mix of quality of life measures, including health, education and economics, to rank the well-being of people country by country.” Sydney Morning Herald (Australia) September 29, 2001.

“The index [HDI] assesses the level of well-being, taking into account three main dimensions. These include life expectancy, adult literacy and enrolment at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels, in addition to the standard of living, measured by purchasing power parity.” Gulf Daily News January 26, 2009.

“The HDR assesses progress by using three main measures of well-being—income, life expectancy and education—to compile a human development index (HDI).” Daily Times (PK) November 5, 2010.

“The HDI represents a push for a broader definition of well-being and provides a composite measure of three basic dimensions of human development: health, education and income.” The Daily Observer (Banjul) January 14, 2011.

“All in all, the countries of the Sahel perform poorly on the UN Development Programme’s Human Development Index, a measurement of a country’s economic and social well-being.” Daily News Egypt, February 10, 2014.

“Yet the HDI is a comparative measure of life expectancy, literacy level, education and standard of living for nations of the world. It is also a standard means of measuring people’s well-being, especially in child welfare.” This Day (Lagos), June 01, 2014.

In the above examples there are interpretations of the HDI, and indeed its components, as being a measure of ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ and in one case it is even regarded as a measure of “child welfare”. In these examples there is no distinction being made between the HDI as gauging the ‘needs’ (inputs) that may be required for ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ and the HDI as a measure of them; it is the latter perspective which dominates.

The relationships between the frequency at which Quality of Life and well-being are used in these articles and the mean adjusted rank of countries based on the HDI are intriguing, and the pattern is different for that seen for reporting of the HDI set out in Fig. 4. For both Quality of Life and well-being (Fig. 5a and b) there is a suggestion that the terms are used more frequently in articles that mention countries having higher HDI ranks (i.e. those that are more developed) relative to those having lower ranks (i.e. are less developed). This difference between the top and bottom end of the rankings is most apparent in Fig. 5b (well-being) where the only statistically significant model is a linear one but is also apparent in Fig. 5a (Quality of Life) where there are two models (quadratic and linear) that are statistically significant. Hence, while both these terms have wide application across newspaper articles that mention the HDI, there does seem to be a greater frequency of their use for countries in the more developed world. Does this suggest that these terms suit a more developed world narrative of the HDI being a measure of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Well-being’? Maybe the journalists feel that this association is one that would resonate better with their readership in those countries than a notion of ‘human development’. Indeed, the UNDP also use ‘well-being’ throughout the HDRs’ but especially those from 2010 onwards, so it is easy to see how the journalists can pick up on that association and use it within their own reporting. But why is there not the same degree of association with ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ in newspaper reporting for countries towards the bottom end of the HDI rankings? This is certainly a question that would warrant more research to explore.

Finally, a reasonable question to ask here is whether media reporting of the HDI matters? Is there any evidence that media reporting of the HDI and the country rankings based upon it has an impact on those with the power to bring about change? Research on the impact of media reporting of indices is at a very embryonic stage of development and literature is scarce. Nonetheless, the importance of this topic has been noted, and Lowrey and Hou (2021; p 37) have concluded with regard to scholarship on the emergence, development, acceptance and persistence of indices:

“These processes are relevant to journalism, not only because of the growing popularity of big data and data visualization but because journalists derive legitimacy and authority from the political-economic institutions that produce most of the data sets. When this dependence is strong, it does little to encourage journalists’ critical thinking. Also, quantitative accounts and data categories, and the scientific practices used to create them, have an aura of authoritative objectivity, and this appeals to beleaguered journalists and news outlets, beset with charges of bias and challenges to their authority.”

Such an “aura of authoritative objectivity” when it comes to indices such as the HDI produced by highly-respected international bodies such as the UNDP can be used by journalists to create a degree of trust in the mind of the reader that truth is being spoken. This matters as:

“Simply put, a significant proportion of the public feels that powerful people are using the media to push their own political or economic interests, rather than represent ordinary readers or viewers. These feelings are most strongly held by those who are young and by those that earn the least.” (Newman & Fletcher, 2017; page 5).

But there are also dangers here with indices seen as ‘abstract constructs’:

“Abstract constructs, through their aggregation of particulars, can efficiently offer new perspectives on the overall landscape. But the processes of commensuration and abstraction can also lead to broad constructs that frame public discussion and public life in simple, powerful ways, becoming unquestioned and naturalized.” Lowrey and Hou (2021; page 47).

Hence indices such as the HDI, even when produced by trusted organisations like the UNDP, are still ‘filtered’ through the interpretations of journalists and reporting may not necessarily chime with what others, including experts, feel is the case. For example, with measures of economic performance it has long been noted that news coverage of them does not necessarily follow the pattern suggested by the information (Boydstun et al., 2018; Soroka, 2006; Soroka et al., 2018). Maybe the same is happening with media interpretation of the HDI, especially for the developed world countries, where higher values for the HDI seem to be equated to greater quality of life and well-being. While the UNDP appear to be content with equating ‘human development’ with ‘well-being’, although perhaps less so with the notion of ‘quality of life’, others may have a less sanguine approach and view the HDI more as an index that attempts to cover the needs (as defined in the HDI—health, education, income) required to achieve well-being rather than being an index of well-being per se. (Jayawickreme et al., 2012). The assumption being made is that having these needs in place generates ‘well-being’, but the story is far more involved than that although the newspaper reporting would appear to suggest otherwise.

5 Conclusions

A number of conclusions can be drawn from the research presented here. Firstly, there does appear to be a relationship between the extent of newspaper reporting of the HDI and the ranking of countries based on the HDI, but the nature of that relationship does depend on the way in which the reporting is assessed. Using number of articles and word count as the metrics does suggest a ‘U’ (quadratic) shaped relationship with countries at the top and bottom of the rankings have more newspaper coverage than those in the middle of the rankings. This matches the pattern seen in other published studies and resonates with the ‘extremity’ hypothesis proposed by Heath (1996) where media attention is greater for those countries at the extremes of the ranking. But using mean article count as the metric presents a different pattern, with countries towards the middle of the rankings having higher average word counts per article than those at the top and bottom. There are various potential explanations for this pattern, and it would certainly warrant further research to explore which are the most likely.

Secondly, the association of the HDI with the terms ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ is common in newspaper reporting, and the index is typically assumed to be a measure of ‘quality of life’ and well-being in countries. The linear nature of the models that emerged from the regression analysis point to a greater frequency of the use of the terms ‘Quality of Life’ and well-being in newspaper articles for countries towards the top of the HDI rankings. (i.e. Those that have better human development) relative to those at the bottom-end of the rankings. This may suggest that the association between reporting of the HDI and ‘quality of life’ and ‘well-being’ is a narrative, at least from the perspective of the journalists writing these stories, that better suits the developed rather than developing world, but why this is so warrants more research. Indeed, research on the media reporting of the HDI, the interpretations and any biases that may be involved, and how these impact upon those with the power to bring out change is at a very early stage and more work is needed to understand the influences that may be involved. The media is, after all, a major vehicle by which devices such as the HDI rankings find their way to a wider audience, and how they report them does make a difference and needs to be given far more consideration in research.

References

Aday, S. (2010). Chasing the bad news: An analysis of 2005 Iraq and Afghanistan war coverage on NBC and fox news channel. Journal of Communication, 60, 144–164.

Anand S and Sen AK 1994. Human Development Index: Methodology and Measurement, Human Development Report Office Occasional Paper, UNDP, New York.

Anand, S., & Ravallion, M. (1993). Human development in poor countries: On the role of private incomes and public services. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(1), 133–150.

Assa, J. (2021). Less is more: The implicit sustainability content of the human development index. Ecological Economics, 185, 107045.

Aturupane, H., Glewwe, P., & Isenman, P. (1994). Poverty, human development and growth: An emerging consensus? The American Economic Review, 84(2), 244–249.

Blancard, S., & Hoarau, J.-F. (2011). Optimizing the new formulation of the United Nations’ human development index: An empirical view from data envelopment analysis. Economics Bulletin, 31(1), 989–1003.

Böhringer, C., & Jochem, P. E. P. (2007). Measuring the immeasurable-A survey of sustainability indices. Ecological Economics, 63(1), 1–8.

Booysen, F. (2002). An overview and evaluation of composite indices of development. Social Indicators Research, 59(2), 115–151.

Boydstun, A. E., Highton, B., & Linn, S. (2018). Assessing the relationship between economic news coverage and mass economic attitudes. Political Research Quarterly, 71(4), 989–1000.

Bravo, G. (2014). The human sustainable development index: New calculations and a first critical analysis. Ecological Indicators, 37, 145–150.

Carlucci, F., & Pisani, S. (1995). A multivariate measure of human development. Social Indicators Research, 36, 145–176.

Cherchye, L., Ooghe, E., & Van Puyenbroeck, T. (2008). Robust human development rankings. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 6(4), 287–321.

Cilingirturk, A. M., & Kocak, H. (2018). Human development index (HDI) rank-order variability. Social Indicators Research, 137, 481–504.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2, 253–260.

Doshi, R., Kelley, J. G., & Simmons, B. A. (2019). The power of ranking: The ease of doing business indicator and global regulatory behavior. International Organization, 73, 611–643.

European Commission. (2009). GDP and beyond. Measuring progress in a changing world. Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament. European Commission, Brussels.

Felce, D., & Perry, J. (1995). Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 16, 51–74.

Garz, M. (2014). Good news and bad news: Evidence of media bias in unemployment reports. Public Choice, 161, 499–515.

Haskins, J. B., & Miller, M. M. (1984). The effects of bad news and good news on a newspaper’s image. Journalism Quarterly, 61(1), 3–13.

Heath, C. (1996). Do people prefer to pass along good or bad news? Valence and relevance of news as predictors of transmission propensity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 68(2), 79–94.

Hickel, J. (2020). The sustainable development index: Measuring the ecological efficiency of human development in the Anthropocene. Ecological Economics, 167, 106331.

Hou, J., Walsh, P. P., & Zhang, J. (2015). The dynamics of human development index. The Social Science Journal, 52, 331–347.

Jayawickreme, E., Forgeard, M. J. C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2012). The engine of well-being. Review of General Psychology, 16(4), 327–342.

Kätsyri, J., Kinnunen, T., Kusumoto, K., Oittinen, P., & Ravaja, N. (2016). Negativity bias in media multitasking: The effects of negative social media messages on attention to television news broadcasts. PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0153712.

Kelly, A. C. (1991). The human development index: ‘Handle with care.’ Population and Development Review, 17(2), 315–324.

Kollmeyer, C. J. (2004). Corporate interests: How the news media portray the economy. Social Problems, 51(3), 432–452.

Kuyken, W., & Group, T. W. (1995). The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the world health organization. Social Science and Medicine, 41, 1403–1409.

Lind, N. (2010). A calibrated index of human development. Social Indicators Research, 98, 301–319.

Lott, J. R., Jr., & Hassett, K. A. (2014). Is newspaper coverage of economic events politically biased? Public Choice, 160, 65–108.

Lowrey, W., & Hou, J. (2021). All forest, no trees? Data journalism and the construction of abstract categories. Journalism, 22(1), 35–51.

McCluskey, J. J., Kalaitzandonakes, N., & Swinnen, J. (2016). Media coverage, public perceptions, and consumer behavior: Insights from new food technologies. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 8, 467–486.

Moldan, B. (1997). The human development index. In B. Moldan, S. Billharz, & R. Matravers (Eds.), Sustainability indicators: A report on the project on indicators of sustainable development (pp. 242–252). John Wiley and Sons.

Morse, S. (2004). Indices and indicators in development. An unhealthy obsession with numbers? Earthscan: London.

Morse, S. (2011a). Harnessing the power of the press with three indices of sustainable development. Ecological Indicators, 11(6), 1681–1688.

Morse, S. (2011). Attracting attention for the cause. The reporting of three indices in the UK national press. Social Indicators Research, 101, 17–35.

Morse, S. (2013). Out of sight, out of mind. Reporting of three indices in the UK national press between 1990 and 2009. Sustainable Development, 21, 242–259.

Morse, S. (2014). Stirring the pot. Influence of changes in methodology of the human development index on reporting by the press. Ecological Indicators, 45, 245–254.

Morse, S. (2016). Measuring the success of sustainable development indices in terms of reporting by the global press. Social Indicators Research, 125, 359–375.

Morse, S. (2018). Focussing on the extremes of good and bad: media reporting of countries ranked via index-based league tables. Social Indicators Research, 139, 631–652.

Neumayer, E. (2001). The Human development index and sustainability–A constructive proposal. Ecological Economics, 39, 101–114.

Neumayer, E. (2012). Human development and sustainability. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 13(4), 561–579.

Newman, N., & Fletcher, R. (2017). Bias, bullshit and lies audience perspectives on low trust in the media. Digital News Project Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism with the support of Google and the Digital News Initiative., 31, 73579.

Nguefack-Tsague, G., Klasen, S., & Zucchini, W. (2011). On weighting the components of the human development index: A statistical justification. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 12(2), 183–202.

Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Harvard University Press.

Ogwang, T. (2000). Inter-country inequality in human development indicators. Applied Economics Letters, 7, 443–446.

Oulton N 2012. Hooray for GDP! Occasional Paper 30. Centre of Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Pinar, M., Stengos, T., & Topaloglou, N. (2017). Testing for the implicit weights of the dimensions of the human development index using stochastic dominance. Economics Letters, 161, 38–42.

Ranis, G., Stewart, F., & Samman, E. (2006). Human development: Beyond the human development index. Journal of Human Development, 7(3), 323–358.

Ravallion, M. (2012). Troubling trade-offs in the Human Development Index. Journal of Development Economics, 99, 201–209.

Rejeski, W. J., & Mihalko, S. L. (2001). Physical activity and quality of life in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56A, 23–35.

Riley, J. C. (2005). Poverty and life expectancy. Cambridge University Press.

Sagar, A. D., & Najam, A. (1998). The human development index: A critical review. Ecological Economics, 25(3), 249–264.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

Sharma, H., & Sharma, D. (2015). Human development index-revisited: Integration of human values. Journal of Human Values, 21(1), 23–36.

Soroka, S. N. (2006). Good news and bad news: Asymmetric responses to economic information. The Journal of Politics, 68(2), 372–385.

Soroka, S., Daku, M., Hiaeshutter-Rice, D., Guggenheim, L., & Pasek, J. (2018). Negativity and positivity biases in economic news coverage: traditional versus social media. Communication Research, 45(7), 1078–1098.

Stapleton, L. M., & Garrod, G. D. (2007). Keeping things simple: Why the human development index should not diverge from its equal weights assumption. Social Indicators Research, 84(2), 179–188.

Streeten, P. (1994). Human development: Means and ends. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 232–237.

Tofallis, C. (2013). An automatic-democratic approach to weight setting for the new human development index. Journal of Population Economics, 26, 1325–1345.

Umberto, L., & Giulia, G. (2021). The gouy-stodola theorem: From irreversibility to sustainability—the thermodynamic human development index. Sustainability, 13(7), 3995.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (1990). Human Development Reports. Available at https://hdr.undp.org/

Wilson, J., Tyedmers, P., & Pelot, R. (2007). Contrasting and comparing sustainable development indicator metrics. Ecological Indicators, 7(2), 299–314.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work and does not have any relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The author also has no conflict interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical statement

The research in the paper did not involve any human subjects or animals and the author has no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morse, S. Quality of Life, Well-Being and the Human Development Index: A Media Narrative for the Developed World?. Soc Indic Res 170, 1035–1058 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03230-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03230-6