Abstract

The origins of financial capability assessed at the country level can be traced back to the socio-economic and quality of life factors. However, the role of national culture should be considered equally important. Hence, differences in national culture are hypothesized to correlate with average financial capability levels at the country level. This study attempts to answer an important question: What is the relationship between culture and financial capability at the country level? The data for this study originate from four diverse sources provided by the World Bank (two datasets), United Nations, and Hofstede Insights. The final dataset includes data from 137 countries. As a measure of financial capability, we use an aggregate index combining financial behavior (account ownership) and financial knowledge. Culture is measured using six dimensions of national cultures from Hofstede Insights: Power Distance, Masculinity, Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism, Long-Term Orientation, and Indulgence. The results show that certain dimensions of culture are strongly correlated with financial capabilities at the country level even after controlling for the level of economic development. Positive relationships between financial capability and three cultural factors—Individualism, Long-Term Orientation, and Indulgence—are noted. In addition, Uncertainty Avoidance is negatively associated with financial capabilities. The observed relationships are non-linear. Specifically, Individualism and Long-Term Orientation are positive correlates of financial capability up to a certain level (the score of 75 and 50, respectively, on the scale 0–100), Individualism is a positive correlate starting at the score of 25, while Uncertainty Avoidance is a negative correlate up to the score of 75.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

At the individual level, consumer financial capability has been shown to correlate with well-being and quality of life (Bialowolski et al., 2022; Taylor et al., 2011; Weida et al., 2020). The role of quality of life indicators including life-expectancy, national income, and education, has been shown to be conducive to creating an environment for financial capability at a country level (Xiao & Bialowolski, 2022). However, beyond that, there are other, national-level factors, whose role in shaping financial capability of a nation has not been sufficiently examined. Undoubtedly, one of such factors is culture. Yet, research focusing on the association between financial capability and country’s culture is limited. This study aims to fill this research gap and combine data on both financial literacy and financial behavior to comprehensively assess the topic of financial capability in the international context.

Unique contributions of this study include examining whether cultural dimensions proposed by Hofstede (2011) are associated with financial capability, which expand the literature of financial capability by adding a potential important determinant. It also enriches the literature of well-being since financial capability is an important determinant of consumer well-being as well. In addition, findings add to the literature of international comparative studies of quality of life since both culture and financial capability are important contributors to the quality of life (Xiao & Bialowolski, 2022).

2 Previous Research and Hypotheses

2.1 National Culture and Its Dimensions

This study adopts theoretical framework developed by Hofstede (2011) to classify culture. Hofstede (2011) claims that “Culture is the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others.” Based on the empirical data collected around the world, Hofstede and colleagues developed six dimensions to measure national culture (Hofstede, 2011; Hofstede et al., 2010). These dimensions include: Power Distance that is related to the different solutions to the basic problem of human inequality; Uncertainty Avoidance that is related to the level of stress in a society in the face of an unknown future; Individualism that is related to the integration of individuals into primary groups; Masculinity that is related to the division of emotional roles between women and men; Long-term Orientation that is related to the choice of focus for people's efforts: the future or the present and past; and Indulgence (versus Restraint) that is related to the gratification versus control of basic human desires related to enjoying life (Hofstede, 2011). These dimensions are widely used in various contexts to measure national culture.

2.2 Financial Capability

Recent trends present a more comprehensive approach to modeling the concept of financial capability. Financial capability is defined differently by various scholars (see a review by Xiao et al., 2022 for details). The most recent approach links the concept with financial knowledge, skills, confidence, and behaviors (Xiao & O’Neill, 2016, 2018; Białowolski et al., 2021). This study defines financial capability as an ability to apply appropriate financial knowledge and perform desirable financial behaviors to achieve well-being (Xiao et al., 2014). Based on this definition, financial knowledge and financial behavior are two important components of financial capability. Although numerous studies have examined factors and consequences of financial literacy and financial behavior (Goyal & Kumar, 2020; Goyal et al., 2021, 2022; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014), little research has examined differences in financial capability between countries or association between culture and financial capability at international level.

2.3 National Culture and Financial Capability

To our knowledge, only several studies based on limited data, approached the link between national culture and financial literacy or financial behaviors using Hofstede’s national culture dimensions. Four studies focused on associations between national culture and financial literacy. Klapper and Lusardi (2020) used data from the 2014 Global Financial Literacy Survey and provided evidence that national financial literacy levels are positively associated with Long-Term Orientation but negatively associated with Uncertainty Avoidance, the two culture dimensions they chose to focus on. De Beckker et al. (2020) used the 2015 OECD/INFE financial literacy survey from 11 countries and two culture dimensions. They found that Individualism shows a negative effect, while Uncertainty Avoidance shows a positive effect on financial literacy. Ahunov and Van Hove (2020) used the same dataset as De Beckker et al. (2020) and found negative effects of Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance and a positive effect of Individualism on financial literacy, while other three culture dimensions did not show any effects. Davoli and Rodríguez-Planas (2020) examined a US nationally representative sample of over 6000 adults from 26 countries of ancestry who participated in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. They linked their data with several datasets including the 2014 Global Financial Literacy Survey. The association between financial literacy in the US and the financial literacy level in their self-reported country of ancestry was found, and the cultural component behind this association included a positive effect of Long-Term Orientation from the country of ancestry.

Three studies examined the association between national culture and financial inclusion. The financial inclusion is usually measured by a bank account ownership, or a variable linked to usage of such an account. In these studies, bank account ownership is considered a proxy of financial behavior. Among these studies, Lu et al. (2021), using data from the 2014 Global Findex, found Individualism (the only cultural dimension examined in that study) to be positively associated with financial service account ownership and its usage. Anyangwe et al. (2022) used data from the 2017 Global Findex and found three positive effects (Individualism, Long-Term Orientation, and Indulgence) and three negative effects (Power Distance, Masculinity, and Uncertainty Avoidance) of culture dimensions on financial behaviors (account ownership, formal saving, and formal debt). Liaqat et al. (2022), using macro data collected from 2004 to 2020 from 81 Belt and Road economies, examined four cultural dimensions. They found two positive effects (Individualism and Masculinity) and two negative effects (Uncertainty Avoidance and Power Distance) of cultural dimensions on financial inclusion (financial access, availability, and usage).

Among seven aforementioned studies that examined the associations between national culture and financial literacy or financial behavior, the associations with cultural dimensions showed mixed patterns. Four studies examined Power Distance and three showed negative effects, while one did not show any effect. Four studies examined Long-Term Orientation and three showed positive effects, while one did not show any effect. Five studies examined Uncertainty Avoidance and four showed negative effects, whereas one showed a positive association. Five studies examined Individualism and four showed positive effects, but one showed a negative one. Three studies examined Masculinity and their results were mixed: first showed a negative, second showed a positive effect, and third showed no effect. Two studies examined Indulgence: one showed a positive effect and the other showed no effect. For four culture dimensions, Power Distance, Long-Term Orientation, Uncertainty Avoidance, and Individualism, we follow the majority of existing studies to propose the hypotheses. For Masculinity and Indulgence, since the existing studies show mixed patterns, we propose null hypotheses. Based on the above literature review and discussions, we propose following hypotheses:

H1

Power Distance is negatively associated with financial capability at international level.

H2

Uncertainty Avoidance is negatively associated with financial capability at international level.

H3

Individualism is positively associated with financial capability at international level.

H4

Masculinity is not associated with financial capability at international level.

H5

Long-Term Orientation is positively associated with financial capability at international level.

H6

Indulgence is not associated with financial capability at international level.

Neither of the studies examined non-linear relationships between cultural dimensions and financial capability or its components. We go one step further and analyze the link between cultural dimensions and financial capability using the approach which allows to identify inflection points and thus elaborate on non-linear associations between culture and financial capability. As there is no research on non-linear patterns in this relationship, we propose a relatively generic hypothesis:

H7

Some cultural dimensions exhibit non-linear relationship with financial capability.

3 Methods

The dataset used in the study was a unique compilation of four datasets from three sources: two from the World Bank, one from the United Nations and one from Hofstede Insights. A global study conducted by the World Bank and supervised by Klapper and Lusardi (2020) allowed to extract information on financial literacy score. The second component of financial capability related to financial behaviors, that is ownership of a bank account, was derived from a global survey conducted by the World Bank. The study measured access to financial products around the world (Demirguc‐Kunt et al., 2015, 2018). National income, education, and life expectancy indicators were from the UN Human Development Report (UNDP, 2015). The cultural dimensions scores were retrieved from Hofstede Insights (https://www.hofstede-insights.com, 2022). There were 80 countries for which all variables were observed. However, after data imputation, final dataset comprised 137 countries (see Fig. 1). Original dataset is available for replication and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KJUUIN.

3.1 Variables

Financial literacy measure used in this study originates from Klapper and Lusardi (2020). They define the financially literate individuals as those who score at least three out of four in their financial literacy test. At the country level, the index is constructed as the share of financially literate individuals among the population of individuals aged 15 or more. The second component of financial capability is bank account ownership. It is also measured at the national level and reflects the percentage of people aged 15 years or older with a bank account (Demirguc‐Kunt et al., 2015, 2018). The aggregate is the financial capability index, which averages financial literacy and financial behavior score at a country level.

Six indexes from the Hofstede culture framework were used as measures of cultural characteristics. Dimensions represent independent preferences for one situation over another that distinguish countries (rather than individuals) from each other. These are Power Distance, Masculinity versus Femininity, Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism versus Collectivism, Long-Term Orientation versus Short-Term Orientation, and Indulgence versus Restraint.

3.2 Control Variables

As earlier studies show, there is a link between country’s level of development and financial capability (Xiao & Bialowolski, 2022). Thus, we decided to use the components of Human Development Index (HDI) as control variables. HDI is considered to be an objective measure of well-being and covers three aspects of life: health reflected by long and healthy life, human capital investment reflected by knowledge, and economic resources reflected by decent standard of living. HDI consists of three dimensions but includes four indicators. The first dimension is measured with life expectancy. The second dimension is assessed with two separate indicators—expected and mean years of schooling. A decent standard of living is captured by the gross national income per capita (UNDP, 2015).

Earlier studies have provided a cross-sectional evidence for a link between financial inclusion, which constitutes part of our financial capability measure, and the incomes of the poorest (Beck et al., 2007). In countries with lower income inequality higher rates of financial inclusion are expected. Thus, in our analyses, we also control for a measure of income inequality (Gini index).

3.3 Analytical Approach

In the initial step, basic statistics for financial capability and its components were computed. The subsequent step was to regress financial capability and its components on national cultural dimensions using a linear regression model. As a significant number of missing data points was identified, multiple imputations were used. Ten randomly generated sets of data were used in the analysis. Imputed data were generated by the chained equations procedure (White et al., 2011). This, under the missing at random (MAR) assumption, allowed to compensate for missingness in controls and cultural dimension variables. In order to obtain final estimates, the Rubin’s formula was applied (Rubin, 1987). It pools the estimates from multiply imputed data. Codes in Stata necessary to replicate the analysis are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/3OV2AV.

Further, in order to examine whether the relationship is curvilinear, multivariate adaptive regression spline (MARS) approach was used. This method helps to identify inflection points in the relationship between a cultural dimension and financial capability (Friedman, 1993). MARS makes an assessment of the relationship between independent variables [in our case, the evaluation of nation’s cultural dimensions (x)] and the outcome variable, that is financial capability or one of its components (y), by aggregating a set of functions (f) to model the relationship between independent variables and the outcome. It takes the following analytical form:

In this approach, base functions (f) can take one of two forms. They can either take the form of a constant function (equal to 1) or alternatively be represented by a hinge function, which is described by the following condition \(f_{i} (x) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\max (0,x - cons_{i} )} \\ {\max (0,cons_{i} - x)} \\ \end{array} } \right.\), where \(cons_{i}\) represents a constant, specific for a given variable i that represents a point, where the relationship between the independent variable and the outcome becomes either steeper of flatter.

To evaluate the robustness of the observed associations between the national culture and financial capability a series of secondary analyses was conducted. We tested the relationship between the national culture and financial capability using (1) single cultural dimensions, (2) including and excluding controls from the analysis, and (3) using data before Imputations (i.e., complete case analysis).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the sample. On average, culture variables ranged from 40.66 (Individualism) to 68.87 (Uncertainty Avoidance). Scores for financial capability, financial knowledge, and financial behavior were 0.53, 0.40, and 0.66, respectively. The average GNI was $23,064 and life expectancy was 75.1 years. The expected and mean schooling were 14.5 and 9.8 years, respectively.

4.2 Results of Regression Analysis

Cultural dimensions are highly correlated with financial capabilities (Table 2). Linear regression results clearly indicate that all dimensions of culture, with the exception of Power Distance and Masculinity, were significant correlates of financial capability. Each point on the scale of Individualism translated into 0.21 points higher score on the financial capability scale. Interestingly, Individualism seemed to have relatively high impact both on the share of financially literate individuals as well as on the proportion of bank account owners. Long-Term Orientation was very significantly related to financial capability—each point on the Long-Term Orientation scale translated into 0.2 points higher score on the financial capability scale. However, when the components of financial capability were analysed separately, Long-Term Orientation demonstrated much stronger link with bank account ownership (coefficient = 0.34) than with the percentage of financially literate individuals (coefficient = 0.06 and not significant). Indulgence was also significantly related to the financial capability index (coefficient = 0.12). Its relationship with bank account ownership was stronger (coefficient = 0.17 but not significant) than with financial literacy (coefficient = 0.08). Inverse relationship between cultural factors and financial capability were observed for Uncertainty Avoidance. Higher Uncertainty Avoidance in a country was predictive of lower financial capability (coefficient = -0.13) but translated less into the financial literacy domain (coefficient = -0.09) than into the bank account ownership (coefficient = - −0.17).

The level of incomes was positively related to financial capability considered as an aggregate but also to its components. Life expectancy and mean schooling in a country were not the factors that demonstrated a significant relationship with either financial capability or its components. However, expected number of years of schooling was correlated with financial capability. This link was particularly apparent for bank account ownership. Gini coefficient was not significantly related with financial capability aggregate but in countries with higher Gini coefficient, lower levels of financial literacy were observed.

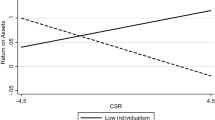

4.3 Results of the MARS Approach

More accurate results regarding the inflection points in the relationship between cultural dimensions and financial capability were identified with MARS approach. From six cultural dimensions, four turned out to be significant in describing financial capability. These were Individualism, Uncertainty Avoidance, Long-Term Orientation, and Indulgence. The analysis confirmed the results of linear regression but also showed presence of certain non-linearities in the relationship between cultural dimensions and financial capability. The positive relationship between Individualism and financial capability breaks when the score for Individualism reaches the level of 70. It shows that achieving the top scores in Individualism is not associated with financial capability beyond a certain point. Even more pronounced effects are present in Long-Term Orientation. In countries exceeding the level of 47 points on the Long-Term Orientation scale, the positive correlation with financial capability disappears. Negative correlations between Uncertainty Avoidance and financial capability, as well as Indulgence and financial capability are present throughout the scale with the exception of countries scoring very high in Uncertainty Avoidance and very low in Indulgence. Consequently, very high Uncertainty Avoidance (above 82 points) and very low Indulgence (below 19 points) do not further imply lower financial capability (Fig. 2).

Non-linear relationship between financial capability and cultural dimensions (only significant are presented) as identified by the MARS approach. Note: The results obtained from a simultaneous estimation of the effects of six Hofstede Dimensions on financial capability. The results from MARS approach support the findings from linear regression indicating that Masculinity and Power Distance are not significant for financial capability

4.4 Robustness

We first tested the relationship between the national culture and financial capability using single cultural dimensions. The results are presented in Table 3 [columns (1)–(6)].

The role of Power Distance was negative when Power Distance was used as the only cultural dimension in the regression. This indicates that other cultural dimensions have larger ability to explain variation in financial capability than the Power Distance. In one-by-one analyses, very strong positive role of Individualism and negative role of Uncertainty Avoidance were confirmed for the financial capability. Interestingly, Long-Term Orientation and Indulgence were not significant predictors of financial capability when included separately. This might indicate that there is a complex pattern of relationships between cultural dimensions and financial capability and all cultural dimensions should be included simultaneously to capture the link between culture and finance at the national level.

Then, the role of controls was tested by excluding them from the analysis [Table 3, columns (7)]. After excluding controls, the role of Uncertainty Avoidance in explaining financial capability was diminished. However, all other cultural dimensions maintained the same direction of relationship with financial capability.

Finally, as a robustness check against missing data patterns, we estimated the primary model without imputations. In this full case scenario [80 observations; Table 3, column (8)], the results were very similar as in the primary model (estimated using multiply imputed data). Four cultural dimensions were related to financial capability and two were not. These secondary analyses provided further evidence for the robustness of the results.

5 Discussion

Among seven hypotheses proposed, five (H2, H3, H4, H5, and H7) are supported and two (H1 and H6) are not supported by the findings.

Our results show that Uncertainty Avoidance, which demonstrates low tolerance for ambiguity and risk-taking behaviors, was negatively linked with financial capability. As people in low uncertainty avoidance cultures are expected to feel more comfortable than those in high uncertainty avoidance cultures in unstructured environments and more openly accept that there is unknown, they might also strive to achieve higher financial capability to mitigate the risks present in the financial domain. Not only are the results consistent with previous research (Klapper & Lusardi, 2020) but also support H2.

The results indicate a positive association between Individualism and financial capability. This supports hypothesis H3 and is also consistent with previous research (Lu et al., 2021). Individualistic cultures require from each member of the society that she/he cares about their finances, and it is an individual responsibility to establish his/her position in the financial domain. In order to achieve high financial status appropriate instruments are needed—a financial compass in the form of financial literacy, as well as a place to accumulate financial resources, namely a bank account. Individuals in collectivistic societies are more inclined to favor relationships and loyalty and thus might not feel a need to organize their finances and have a complete control over this sphere.

Our results show that Masculinity is not associated with financial capability, which is consistent with H4. Previous studies revealed mixed evidence in this realm (Anyangwe et al., 2022; Liaqat et al., 2022). Our findings add evidence for the potential lack of effect of this cultural factor on financial capability. Thus, it does not confirm that in more feminine cultures where cooperation, nurturing and emphasis on the quality of life are expected to grow, an environment conducive for financial capability growth is observed. There is also no evidence that in masculine societies, where larger emphasis is placed on competition, strength or courage, the financial resources become less important. This indicates that management of financial resources in the form of financial capability can be considered a secondary objective from the perspective of Masculinity.

The results also show a positive association between Long-Term Orientation and financial capability. High scores in this cultural dimension are characteristic for cultures that encourage delayed gratification. Thus, individuals living in such cultures might adopt a longer life perspective. This can translate into individual behavior oriented to saving for the future. Presence of Long-Term Orientation was particularly associated with the bank account ownership, which indicates that it translates mostly into financial product ownership and to a lower extent into financial literacy gains. Our results support H5. They are also consistent with previous research (Anyangwe et al., 2022).

Finally, also H7, which concerns non-linear relationship between cultural dimensions and financial capability, is supported by our results. Since no previous studies examined the non-linear relationship between these two phenomena, these findings are new contributions to the literature.

Two hypotheses are not supported by the findings. Among them, H1 predicts that Power Distance is negatively associated with financial capability. Our results show that the association is not statistically significant. However, the coefficient of Power Distance is negative and marginally significant when financial literacy is predicted, which is consistent with previous research (Ahunov & Van Hove, 2020). The result suggests that in a culture when Power Distance is high, consumers may demand less financial knowledge than in a culture that is low in Power Distance.

H6 was not supported by the findings either, since we found that Indulgence is positively associated with financial capability instead of no association as hypothesized. As the existing studies provided mixed evidence (Ahunov & Van Hove, 2020; Anyangwe et al., 2022), the findings here add evidence to show the potential effect of indulging in life on financial capability. Additionally, our results indicate that more indulgent culture is also more likely to emerge in a developed economy.

6 Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications

An international dataset compiled from three sources was used to examine the association between national culture and financial capability. Linear regression results show that Individualism, Long-Term Orientation, and Indulgence are positively, while Uncertainty Avoidance is negatively associated with financial capability. Additional linear regression results show similarities and differences of associations between culture dimensions and the two components of financial capability. Two dimensions show similar patterns, in which Individualism is positively and Uncertainty Avoidance is negatively associated with both financial literacy and financial behavior. Four cultural dimensions show different patterns of associations with financial literacy and financial behaviors. However, in a more detailed analysis, Power Distance turned out to be negatively related to financial literacy. With respect to financial behaviors, Long-Term Orientation and Indulgence show positive effects. Further analyses demonstrate non-linear associations between four cultural dimensions and financial capability. Specifically, on financial capability, the positive effects of Individualism and Long-Term Orientation cease at about a score of 75 and 50, respectively, the positive effect of Indulgence emerges only at the score of approximately 25, and the negative effect of Uncertainty Avoidance ends at about 75.

Limitations of this study need to be acknowledged before implications are discussed. First, compete cases of data were available for 80 countries only (mostly due to limited availability of cultural dimensions). Majority of African countries had some data availability issues. Thus, the sample was skewed in the direction of more developed countries. However, after imputations, data for 137 countries were available for analysis and a lot of missingness from Africa was accounted for. In future research, more countries should be included when data on national culture information becomes available. Second, this study examined the association between culture and financial capability at national level and no causality can be directly implied from the data. Evidence can be only viewed suggestive. To confirm the cause-effect relationship, more sophisticated panel or experimental data are needed (which are not available at this moment). However, the theoretical arguments for causality in the proposed direction are strong as national culture being stable and long-lasting clearly precedes financial behaviors and financial choices. Third, the financial literacy scale that we used focuses on numeracy. Consequently, it measures financial skills rather than financial knowledge. Future research could replicate the analyses using a more balanced measure comprising financial skills, financial knowledge, and financial attitudes. Unfortunately, we are not aware of such an instrument that is available and comparable for a substantial number of countries. Finally, the financial capability variable is composed of two variables, which may not capture the full picture of financial capability. In future research, more variables measuring financial capability should be explored and included in international comparison studies. If available, a more robust measure of financial capability, like the one proposed by Atkinson et al. (2006), could be used. This more comprehensive measure of financial capability might include dimensions like managing money, keeping track of expenses, planning ahead, selecting financial products, and staying informed. Future research could also look at the relationship between financial capability and other variables such as materialism, consumerism, and frugality as well as use break downs by degree of urbanization. Keeping the limitations in mind, results of this study have implications for public policies. Countries aiming to promote financial capability may consider different cultural features since these features may enhance or hamper development of financial capability. For a country high in Individualism, promoting both financial literacy and financial behavior are desirable since the policies may receive support from the culture. For a country low in Individualism, promoting financial capability may be difficult and policy makers may want to design special policies to encourage the development of financial capability for improving financial well-being.

Public policy makers may also consider potential differentiated effects of culture features on financial capability. For example, Uncertainty Avoidance is negatively associated with financial capability. In a country with high Uncertainty Avoidance, conducting financial literacy interventions may encounter more barriers than in a country that is low in this dimension of culture. The policy makers in these coutnries may need to consider additional strategies to overcome barriers when they promote financial literacy education for improving the welfare of the population.

Policy makers may also be aware of the non-linear relationships between culture dimensions and financial capability. For example, the positive association between Long-Term Orientation and financial capability only exists in countries that have the score of Long-Term Orientation of about 50 or lower. Above that score, the association disappears. The finding suggests that among countries that are low in Long-Term Orientation, public policies emphasizing the value of long-term planning may help to promote financial capability. But among countries that are high in Long-Term Orientation, this type of policy may not be effective.

References

Ahunov, M., & van Hove, L. (2020). National culture and financial literacy: International evidence. Applied Economics, 52(21), 2261–2279. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1688241

Anyangwe, T., Vanroose, A., & Fanta, A. (2022). Determinants of financial inclusion: does culture matter? Cogent Economics & Finance. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2073656

Atkinson, A., McKay, S., Kempson, E., & Collard, S. (2006). Levels of Financial Capability in the UK: Results of a baseline survey. Consumer Research, 46, 1–150.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2007). Finance, inequality and the poor. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-007-9010-6

Białowolski, P., Cwynar, A., & Cwynar, W. (2021). Decomposition of the financial capability construct: A structural model of debt knowledge, skills, confidence, attitudes, and behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 32(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1891/JFCP-19-00056

Bialowolski, P., Cwynar, A., & Weziak-Bialowolska, D. (2022). The role of financial literacy for financial resilience in middle-age and older adulthood. International Journal of Bank Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-10-2021-0453

Davoli, M., & Rodríguez-Planas, N. (2020). Culture and adult financial literacy: Evidence from the United States. Economics of Education Review, 78, 102013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.102013

de Beckker, K., de Witte, K., & van Campenhout, G. (2020). The role of national culture in financial literacy: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(3), 912–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12306

Demirguc‐Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & van Oudheusden, P. (2015). The Global Findex database 2014: Measuring financial inclusion around the world. Policy Research Working Paper; No. 7255. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/21865

Demirguc‐Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The Global Findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/29510

Friedman, J. H. (1993). Estimating functions of mixed ordinal and categorical variables using adaptive splines. In S. Morgenthaler, E. Ronchetti, & W. Stahel (Eds.), New directions in statistical data analysis and robustness. Birkhause: Basel.

Goyal, K., & Kumar, S. (2020). Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(1), 80–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12605

Goyal, K., Kumar, S., & Xiao, J. J. (2021). Antecedents and consequences of Personal Financial Management Behavior: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(7), 1166–1207. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-12-2020-0612

Goyal, K., Kumar, S., Xiao, J. J., & Colombage, S. (2022). The psychological antecedents of personal financial management behavior: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(7), 1413–1451. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-02-2022-0088

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede Model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2, 1–26.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Klapper, L., & Lusardi, A. (2020). Financial literacy and financial resilience: Evidence from around the world. Financial Management, 49(3), 589–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12283

Liaqat, I., Gao, Y., Rehman, F. U., Lakner, Z., & Oláh, J. (2022). National Culture and Financial Inclusion: Evidence from Belt and Road Economies. Sustainability, 14(6), 3405. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063405

Lu, W., Niu, G., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Individualism and financial inclusion. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 183, 268–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.01.008

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.1.5

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for non response in surveys. New York: Wiley.

Taylor, M. P., Jenkins, S. P., & Sacker, A. (2011). Financial capability and psychological health. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32, 710–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.05.006

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2015. Human Development Report 2015: Work for Human Development. New York.

Weida, E. B., Phojanakong, P., Patel, F., & Chilton, M. (2020). Financial health as a measurable social determinant of health. PLoS ONE, 15(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233359

White, I. R., Royston, P., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine, 30, 377–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4067

Xiao, J. J., & Bialowolski, P. (2022). Consumer Financial Capability and Quality of Life: A Global Perspective. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-022-10087-3

Xiao, J. J., Chen, C., & Chen, F. (2014). Consumer financial capability and financial satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 118, 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0414-8

Xiao, J. J., Huang, J., Goyal, K., & Kumar, S. (2022). Financial capability: A systematic conceptual review, extension and synthesis. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(7), 1680–1717. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-05-2022-0185

Xiao, J. J., & O’Neill, B. (2016). Consumer financial education and financial capability. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(6), 712–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12285

Xiao, J. J., & O’Neill, B. (2018). Propensity to plan, financial capability, and financial satisfaction. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(5), 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12461

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bialowolski, P., Xiao, J.J. & Weziak-Bialowolska, D. National Culture and Financial Capability: A Global Perspective. Soc Indic Res 170, 877–891 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03221-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03221-7