Abstract

This study utilized instrumental variable techniques and the Driscoll-Kraay estimator to examine the effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality using a comprehensive panel dataset from 43 sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The findings from our empirical analysis indicated that natural resources and democracy indices such as electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian drive income inequality in SSA. Regional comparative analysis also showed that the democracy indices increase income inequality in West, Central, and Southern Africa while having a neutral effect on income inequality in Eastern Africa. Natural resources were revealed to reduce income inequality in West and Southern African countries while increasing income inequality in Eastern Africa. In the case of Central Africa, natural resources play an insignificant role in income inequality. The interactive effect analysis indicates that the democracy indices interact with natural resources to increase income inequality in SSA. Finally, the democracy indices interacted with natural resources to drive income inequality in Eastern and Southern African countries while exerting an insignificant effect on income inequality in West and Central African countries. The policy implications of the findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper investigates the direct and interactive role of natural resources and democracy on income inequality in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The pursuit of development in many developed and developing countries is increasingly dependent on natural resources, both renewable and non-renewable. It is well known that natural resources have a wide range of effects on vital global systems, such as political and economic systems (Gylfason, 2001; Havranek et al., 2016; Humphreys et al., 2007; Toews, 2006; Young, 1989). In many developing countries, access to natural resources improves productivity, boosts economic growth, promotes export opportunities, creates employment, and decreases poverty (Asif et al., 2020; Dinye & Erdiaw-Kwasie, 2012; Ebeke & Etoundi, 2017; Schandl et al., 2018). To the local communities, natural resources can provide employment opportunities, infrastructure development, and involvement in decision-making (Ojha et al., 2016; Shereni & Saarinen, 2021). Moreover, natural resource endowments contribute to fiscal revenue income, poverty reduction, and the creation of jobs.

Resources in abundance can indeed be a blessing. For example, Norwegian petroleum production has added some US$2,010 billion to the country’s GDP over the past half-century, and the sector now accounts for 21% of the country’s total value creation (Nwankwo & Iyeke, 2022). By drawing effectively on its vast copper reserve, Chile has also experienced astonishing economic growth in the Global South in real terms compared to the rest of Latin America (Fernandez, 2021; Pietrobelli et al., 2018). However, the case is different in SSA. Natural resources in SSA are plentiful and diverse. African resources are, in fact, among the most varied on the planet (Dwumfour & Ntow-Gyamfi, 2018; Mlambo, 2019; Sachs & Warner, 2001). However, the abundance of natural resources in SSA has been the subject of many debates concerning the level of development in the region in comparison with other parts of the world (Erdogan et al., 2020; Zallé, 2019a). In other words, the contribution of natural resources to the development trajectory of SSA countries is still contentious. Due to this, the region has become a textbook case of the resource curse, characterized by natural resource abundance, low economic development, and mismanagement of natural resources (Badeeb et al., 2017; Dwumfour & Ntow-Gyamfi, 2018; Frynas et al., 2017). In this context, the term resource curse refers to the phenomenon of countries with abundant natural resources growing more slowly than those without abundance.

While the existing literature has extensively explored the effect of natural resources on economic growth (Epo et al., 2020; Haseeb et al., 2021; Hayat & Tahir, 2021; Zallé, 2019a), the effect of natural resources on income inequality remains limited in the empirical literature (Alvarado et al., 2021; Hartwell et al., 2019). Theoretically, the effect of natural resources on income inequality remains ambiguous. Based on the resource curse hypothesis, one stream of the literature argues that natural resources can widen income inequality. For example, Hartwell et al. (2019) argue that natural resources can widen income inequality by stifling export diversification. The authors indicated that in the presence of abundant natural resources, countries tend to over-depend on the exportation of primary goods, limiting export diversification and industrialization, thereby increasing income inequality. In addition, Alvarado et al. (2021) argue that natural resources can worsen income inequality through natural resources’ prices. Thus, while natural resources abundant regions/countries tend to depend heavily on natural resources, a decrease in the price of natural resources would decrease the income of the factor such as labor that is intensively used in the extraction of natural resources and, thus, widens income disparity (Alvarado et al., 2021). Also, a decrease in the price of natural resources will reduce the government revenue needed to implement pro-poor infrastructures and policies and thus widen income inequality.

Similarly, a decrease in the price of natural resources could worsen terms of trade by generating or enforcing a negative trade balance, causing an imbalance of payments, or widening existing imbalances in international payments (Anderson & Yotov, 2016; Henry, 2019; Papyrakis & Gerlagh, 2004). In their study, Anderson and Yotov (2016) elaborate on how worsened terms of trade could lead to declining employment and income levels of people employed in the natural resource sector. Drawing insights from these studies, there could also be flow-on effects causing fluctuations in consumption and aggregate demand, especially if a resource-rich country does not have other means to smoothing consumption and economic activities. Moreover, due to forward–backward linkages of economic activities to industries, changes in terms of trade resulting from changes in prices could have a pronounced effect on income inequality, especially if the proportion of natural resources in the gross domestic product is large. Contrarily, some scholars believe that natural resource abundance can reduce income inequality. Hartwell et al. (2019) added that natural resource abundance could improve income equality by raising the income of low-skilled workers in the extractive natural resources sectors. Similarly, Alvarado et al. (2021) argue that when the price of natural resources increases, it raises labor income, thus reducing income inequality.

In discussing the effect of natural resource abundance on income inequality, the role played by a countries’ political institutions or system cannot be overlooked. For instance, Hartwell et al. (2019) stated categorically that the contribution of natural resource abundance in reducing income inequality depends on countries’ political institutions and, for that matter, democracy. Thus, the existence of political institutions that ensures effective redistribution of natural resource rent to benefit poorer people, which form the majority of the population, rather than concentrating such rents in the hands of a few wealthy people, can bridge the income gap (Hartwell et al., 2019; Parcero & Papyrakis, 2016a). Anderson and Aslaksen (2008) claim that the resource curse is more prevalent in countries practicing presidential democracy than those with parliamentary democracy as their preferred form of government. In recent studies that have examined the relationship between democracy and the resource curse, it was found that high rents in government budgets make it possible for governments to maintain low tax rates, relieving accountability concerns (Azfar et al., 2018; Badeeb et al., 2017; Farhadi et al., 2015). The poor accountability systems and a lack of citizen involvement in national budgets make it easier for corrupt officials to divert natural resources’ income.

A critical examination of the existing studies reveals that studies have examined either the effect of natural resources on economic growth or democratic governance in different regions and countries (Caselli & Tesei, 2016; Hartwell et al., 2019; Ross, 2015). However, a paucity of empirical studies has examined the effect of natural resource abundance and democracy on income inequality in tandem (for instance, see Hartwell et al., 2019). Additionally, the results of the existing studies investigating either effect of the resource curse or democracy on income inequality are inconsistent and inconclusive (Ahmadov, 2014; Kim et al., 2020; O’Connor et al., 2018; Parcero & Papyrakis, 2016a; Smith, 2015). In addition, there have also been few studies that have addressed the resource curse, democracy, and inequality in SSA (Bergougui & Murshed, 2020; Mlambo, 2022; Smith, 2015). Thus, to our knowledge, the joint effect of the natural resource curse and democracy on income inequality in SSA has not been given the needed attention.

Another limitation in the existing literature is that they failed to examine the interactive effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality. The argument is that political institutions, especially democracy, condition the effect of natural resource abundance on income inequality. Given the fundamental role of political institutions (democracy) on countries’ redistributive policies, how democracy conditions natural resources to affect income inequality has only been superficially incorporated into the political economy discussions and the existing empirical studies (Hartwell et al., 2019). Hartwell et al., (2019; page 532) hypothesize that “democratic institutions prevent extreme income polarization in a country blessed with natural resource endowments.” Empirically, these authors demonstrated that resource rents have a neutral effect on income inequality unless one considers political institutions, indicating that democratic countries tend to minimize resource-related inequality relative to more authoritarian states.

Another loophole in the existing studies relates to how democracy as a variable was measured. Prominently studies on the effect of democracy on income inequality have relied on using Polity II/IV Project, Freedom House, or the International Country Risk Guide democracy variable (Balcázar, 2016; Hartwell et al., 2019; Reuveny & Li, 2003). The democracy variables from these databases have been criticized for their reliability and validity, coding, aggregation, coverage, and sources (see Coppedge et al., 2011). For instance, it has been argued that democracy variables from these reputable databases are not sensitive to the relevant time changes or changes in the quality of democracy across countries (Coppedge et al., 2011). Additionally, as democracy is a multi-dimensional concept, Coppedge et al. (2011) argue that democracy variables from these databases are narrowly defined to imply elections, and the aggregation approach to derive a democracy index poses a challenge to the meaning and accuracy of what democracy means at large. Thus, democracy goes beyond the mere definition of an election, and for that matter, valid, reliable, and precise democracy indices are needed for empirical research to draw valid conclusions and policy suggestions. As recommended in the work of Hartwell et al. (2019), using an aggregated measure of democracy limits understanding of how democracy affects natural resources and income inequality relationship; therefore, further studies using varieties of high-level democracy indices would contribute significantly to understanding how different high-level democracy indices affect income inequality and further conditions natural resources to affect income inequality.

This study, therefore, fills the identified research gaps and offers more comprehensive insights into the direct and indirect effects of natural resources and democracy on income inequality in SSA. Specifically, the following research questions are addressed in this study:

-

1.

Do natural resources contribute to income inequality reduction in SSA?

-

2.

Does institutionalized democracy improve income inequality reduction in SSA?

-

3.

Does democracy condition natural resources to improve income inequality in SSA?

-

4.

Does the direct and indirect effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality differ among the sub-regions within SSA?

Our study, therefore, contributes to the existing literature on natural resources, democracy, and inequality in the following ways. First, our study contributes to the literature by examining the empirical relationship between resource curse, democracy, and inequality in the SSA region. SSA is an interesting case for this study because the region has a high-income inequality while being rich in natural resources. Moreover, some countries in the region are experimenting with democracy and are at different stages of democracy. Second, our study enriches the literature by using five high-level democracy indices, including electoral democracy, liberal democracy, participatory democracy, deliberative democracy, and egalitarian democracy, to examine their respective effect on income inequality in SSA and how they further condition natural resources to affect income inequality in SSA. These democracy indices are sourced from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) database developed by Coppedge et al. (2018). The V-Dem overcomes most of the limitations in the previous democracy variables, which have been applied to existing empirical studies. Third, our paper contributes to the literature by exploring how the democracy indices moderate natural resources to affect income inequality in SSA. This conditional effect analysis is critical since it will contribute to discussions on how natural resource rent in democratic countries affects income inequality relative to autocratic countries. In addition, it will contribute to the understanding of how political institutions shape the redistribution of natural resource rent to the benefit of poorer people rather than concentrating such rents in the hands of a few wealthy people. Fourth, as natural resources and democratic regimes differ among sub-regions in SSA, we avoid the assumption of homogeneity in our sample and comparatively analyze how the effect of natural resources and democracy on income inequality differs among the sub-regions in SSA. Finally, our study is timely since its findings will contribute significantly to the design and implementation of policies that seek to address income inequality, which is one of the central tenants of the sustainable development goals in SSA.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 discusses the literature review, and Sect. 3 discusses the methodology and data. The empirical results and discussions are presented in Sect. 4, and the discussion and policy implications appear in Sect. 5.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Natural Resources and Income Inequality

Generally, societies endowed with abundant natural resources should have higher economic performance and enhance the socio-economic well-being of their citizenry. This is because renewable or non-renewable natural resources are central to human existence, and benefits could be invested to improve physical and human capital (Anyanwu et al., 2021; Davarzani, 2022; Sebri & Dachraoui, 2021). However, over the past decades, several empirical evidence and theory have shown that natural resource endowments do not necessarily or always translate into political and economic development, income parity, poverty reduction, and democratic outcomes (Scognamillo et al., 2016; Lessmann & Steinkraus, 2019; Shaygan Mehr, 2022; Khan et al., 2022; Brooks, 2022; Postigo et al., 2021). This phenomenon is termed the ‘paradox of resource curse’ or ‘paradox of plenty’ (see Gelb, 1988; Auty, 2002; Chekouri et al., 2017; Awoa, 2022). In light of this, research on the linkages between natural resources, socio-economic development, and democracy, though it has received enormous attention in the literature and among policymakers, remains a contested field.

The relationship between natural resource abundance and income inequality can be examined from the natural resource curse lens (Havranek et al., 2016; van der Ploeg & Poelhekke, 2017). Theoretical and empirical findings on natural resources’ impact on income inequality have revealed a striking heterogeneity (Bearce, 2011; Rapanyane, 2021; Anyanwu et al., 2021; Tshinu, 2022; Mlambo, 2022). Theoretically, Bourguignon and Morrison’s (1990) and Spilimbergo et al. (1999) models highlight that resource endowment worsens income inequality. Carmignani (2013) confirmed earlier results in his study that used cross-sectional data from 1970 to 2010 in 84 countries. Also, utilizing growth regressions and cross-country data between 1980 and 1995, Atkinson and Hamilton (2003) provided evidence that mismanagement of natural resources by governments negatively impacts income inequality. Similarly, using cross-sectional data, (Gylfason & Zoega, 2003) discovered that oil resource endowment positively correlates with income inequality. In their study, Gylfason and Zoega indicate that unequal distribution of natural capital in an economy widens income gaps. The natural resource curse has also been found in ethnically divided societies through increasing rent-seeking contests and civil conflicts (Hodler, 2006; Brunnschweiler, 2008; Kopiński et al., 2013). Alesina and Glaeser (2004) mention that the resource curse is more prominent in divided societies and ethnically polarised regions than in homogeneous ones. Further, Leamer et al. (1999) mention that the abundance of natural resources, such as land, might sometimes result in lower human capital formation, leading to higher levels of income inequality. This supports recent findings from Cockx and Francken (2016), who concluded that education spending does not increase more in resource-rich countries. To sum it up, Gavin and Hausmann (1998) link the widening income inequality gap in natural resource-rich countries to; (i) less labor productivity and wages,(ii) sunk capital, and (iii) volatility in the natural resource market. Other equally important factors in the resource curse debate include revenue mismanagement and poor governance (Adams et al., 2019; Mlambo, 2022; Hussain et al., 2021), corruption (Frynas & Buur, 2020; Kordbacheh & Sadati, 2021), socio-economic, political crisis and regional conflicts (Adhvaryu et al., 2018; Bruch et al., 2019). Amidst these studies with positive correlations between natural resource abundance and income inequality, others have shown a negative relationship.

Elsewhere, Goderis and Malone (2011), using fixed-effects estimation and a panel of 90 countries from 1965 to 1999, revealed that the discovery of a large number of natural resources potentially limits income inequality permanently. Smith (2015) examined oil discovery data from three developed countries and showed that the resource boom either has no significant impact on income inequality or can reduce income inequality. Smith concludes that the impact of the natural resource boom is highly dependent on the location and the quality of available institutions. According to (Ross, 2015), another way natural resource abundance bridges the income inequality gap is when revenues generated are used to create additional public sector jobs. Ross contends that horizontal income inequality is reduced when natural resource extraction commences in a poorer region than the rest of the country. Kim and Lin (2018), who employed cross-country data, demonstrated that oil abundance lowers income inequality due to higher educational attainment and improved health. Mehlum et al. (2006) and Hartwell et al. (2019) also found that natural resource abundance can raise incomes in a producer-friendly institutional environment.

2.2 Democracy and Income Inequality

Adding to the above discussion, resource curse debates have gained popularity in political regime studies. On the redistributive and equality effect of democracy, Acemoglu, Naidu, Restrepo, and Robinson (2015) argue that democracy can increase redistribution and reduce income inequality; however, this assumption can fail if democracy is captured by the wealthier proportion of the population, caters for the preference of middle-class and opens up disequalizing opportunities. Democracy, in principle, should ensure the protection of everyone, particularly the poor, through the redistribution of resources equitably via taxation and the provision of public services (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2006; Acemoglu et al., 2019). This stems from the fact that democracy reallocates powers among elites, middle classes, and poorer segments of society, encouraging egalitarian resource distribution (Lipset, 1959; Meltzer and Richard, 1981). However, the link between democracy and income inequality is inconclusive, with mixed findings (Sirowy and Inkeles, 1990; Gradstein et al., 2001). Ziblatt (2008), in his study, found that democracy fails to reduce income inequality in low-capacity states compared to high-capacity states. This is because elites in most low-capacity democratic states escape taxes, limiting the ability to implement redistributive policies and provide public goods and transfers. On the other hand, Bahamonde and Trasberg (2021) counter this point by arguing that high-capacity democratic settings increase income inequality through two policy streams-financial development and larger foreign direct investment (FDI) flows. According to them, larger FDI flows affect market inequality by increasing the demand for skilled workers and creating a sector of high-wage earners and a large low-wage backyard sector.

Andersen and Aslaksen (2008) found that the resource curse is more prominent in countries practicing presidential democracy, unlike countries inclined to a democratic parliamentary system of governance. Adams et al. (2019) also contend that the natural resource curse mostly occurs in developing countries. For instance, Kolstad and Wiig (2009) and Frankel (2010) showed that the natural resource curse contributes to a weakening democratic process in SSA. Supporting this argument, Van Gyampo (2016) and Gyimah-Boadi and Prempeh (2012) illustrate gaps in legislative and regulatory frameworks and institutions that underpin inadequacies in Ghana’s democratic dispensation. Bhattacharyya and Hodler (2010) state that the quality of institutions positively impacts resource-curse escape. Another study by Arezki and Gylfason (2013), who employed both OLS and the dynamic system GMM approach for 29 SSA, found that higher resource rents trigger corruption, especially in less democratic countries.

In another study, Balcázar (2016) used comparable micro-data and pseudo-panels to illustrate that democracy offsets income inequality and associated issues. In Latin America, Huber and Stephens (2012) found that income inequality declines after an extended period of economic growth and democratization. Finally, Acemoglu et al. (2015) and Acemoglu and Robinson (2008) point out that democracy can reduce income inequality when holding political power and controlling the political process is prevented. These studies conclude that the quality and coverage of democratic institutions matter more than their presence.

3 Methodology and Data

3.1 Specification of the Empirical Model

In this study, we augment the popular Kuznets (1955) income inequality-economic growth framework with natural resource and democracy variables. The Kuznets (1955) curve is an important framework that postulates an inverse relationship between income inequality and economic growth. Therefore, in this study, we specify that income inequality is a function of economic growth, economic growth squared, natural resources, democracy, and other control variables that affect income inequality. Equation (1) is the reduced-form static model for estimating the effect of natural resources and economic growth within the Kuznets (1955) income inequality-economic growth framework.

To contribute to the political economy literature, we hypothesize that democracy conditions natural resources to affect income inequality. This argument stems from the fact that a country’s political institutions and, for that matter, democracy is an important mechanism for transforming resource rents or resource abundance to reduce income disparity (Hartwell et al., 2019). We test how democracy conditions natural resources to affect income inequality in SSA. Equation (2) is the empirical model for estimating the interactive effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality.

From Eq. (2), we differentiate income inequality with respect to natural resources to obtain Eq. (3). Therefore, Eq. (3) is the marginal effect equation for calculating the marginal or net effectsFootnote 1 of natural resources on income inequality based on the interaction between natural resources and democracy. In this paper, we evaluated the net effect of natural resources on income inequality at the maximum values of democracy variables.

where \(i=1\dots \dots ..N\) and \(t=1990\dots \dots . 2017.\). \(lngdp\) is the natural logarithm of GDP per capita; \({lngdp}^{2}\) is the natural logarithm of GDP per capita squared; \(lntnresou\) is the natural logarithm of natural resources; \(demo\) is a democracy variable, and \(X\) is the natural logarithm of a set of control factors that potentially affect income inequality. \({\alpha }_{1}\) is the constant parameter. \({\theta }_{1}\) is the coefficient of economic growth to be estimated; \({\theta }_{2}\) is the coefficient of economic growth squared to be estimated; \({\theta }_{3}\) is the coefficient of natural resources to be estimated; \({\theta }_{4}\) is the coefficient of democracy to be estimated. \({\delta }_{2}\) is the coefficient of the interaction term of democracy and natural resources to be estimated; \({\gamma }_{1}\) the coefficient of the set of control variables to be estimated and \({\varepsilon }_{it}\) is the stochastic error term. In this study, we expect \({\theta }_{1}>0 and {\theta }_{2} <0;\) \({\theta }_{3} <0\) and\({\theta }_{4} <0\). Following existing studies, we account for seven (7) control variables that affect income inequality. These variables include trade openness, foreign direct investment, government expenditure, education, inflation, domestic investment, and foreign aid (Acheampong et al., 2021; Anderson et al., 2017; Bergh & Nilsson, 2010; Chong et al., 2009; Enowbi Batuo et al., 2015; Glomm & Ravikumar, 2003).

3.2 Estimation Strategies

Estimating the above equations with the ordinary least-squares (OLS) technique can generate biased results because of its inability to account for the endogeneity issue. Thus, in the presence of endogeneity, OLS can cause attenuation bias by downward biasing the estimates (for instance, see Acemoglu et al., 2001). Endogeneity can emanate from reverse causality, measurement errors, and variable omission bias. This study employs instrumental variable (IV) regression techniques to address potential endogeneity in our empirical models. Thus, the empirical models are estimated using the Baum, Schaer, and Stillman (2002) instrumental variable generalized method of moment (IV-GMM). The application of the IV-GMM is essential since its estimates are robust to autocorrelation, and even in the presence of unknown heteroscedasticity, it can generate consistent estimates since it uses the orthogonality condition (Baum et al., 2002). Applying the IV-GMM requires an exogenous instrument for the endogenous variable. However, Stock, Wright, and Yogo (2002) argue that finding the appropriate exogenous instrument for applied research is challenging. Therefore, in this study, we use lags 1 and 2 of the democracy variables as an instrument for the democracy indices (the endogenous variables).

Some econometricians, including Baum et al. (2012) and Stock et al. (2002), indicate that appropriate instruments for identifying the empirical model should have a correlation with the endogenous variable, satisfy orthogonality conditions, and must be appropriately excluded from the model so that their effect on the main dependent variable is only indirect. Although we use lags 1 and 2 of democracy as instruments in the IV-GMM model, they may not satisfy these conditions simultaneously. Regarding these arguments, we further apply the Lewbel (2012) two-stage least squares (TSLS) technique, which is used when the sources of identification, such as having appropriate external instruments are not available or weak. The Lewbel (2012) TSLS approach is important for identifying structural parameters in the regression models with endogenous or mismeasured regressors. The Lewbel (2012) TSLS estimator generates internally constructed heteroskedasticity-based instruments. These internal heteroskedasticity-based instruments are generated from the auxiliary equation residuals, which are multiplied by each of the included exogenous variables in mean-centered form. It is argued that the estimate from the Lewbel (2012) TSLS technique does not rely on satisfying standard exclusion restrictions. Lewbel (2012) argues that the estimates from Lewbel TSLS estimator without any external instruments are very close to those obtained using external instruments.

In addition to the IV estimators, we also estimated Eqs. (1–2) using the Driscoll-Kraay estimation technique. The Driscoll and Kraay (1998) estimation technique, based on a nonparametric time series covariance matrix estimator, assumes that the error structure is heteroscedastic, autocorrelated up to some lag, and perhaps correlated between the panels. Also, the Driscoll–Kraay nonparametric estimator produces robust results in both cross-sectional and temporal dependence (Hoechle, 2007). The Driscoll–Kraay estimation technique can also handle missing data series and works with balanced and unbalanced panels (Hoechle, 2007).

3.3 Data Description

This study employs a comprehensive panel dataset for 43 SSAFootnote 2 from 1990 to 2017 to examine the effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality. This study uses the income inequality data from Solt’s (2016) Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) for the dependent variable. This study used the SWIID Post-tax/transfer Gini index of income inequality as a proxy for income inequality. It combines and standardizes inequality data from various income inequality databases such as the World Income Inequality Database, Luxembourg Income Studies, and World Income Distribution Data (Solt, 2016). The SWIID Gini coefficient has been widely used in applied research (Acheampong et al., 2021; Brueckner & Lederman, 2018; Jauch & Watzka, 2016).

To contribute significantly to the literature, this study uses five high-level democracy indices, including electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian democracy, which are used in this study. The definitions of each of the democracy indices, according to Coppedge et al. (2011), are presented in Table 1. Also, in this study, we use total natural resource rents (% of GDP) as an indicator of natural resources. Total natural resources rents are the sum of oil rents, natural gas rents, coal rents (hard and soft), mineral rents, and forest rents.

For the control variables, we follow the income inequality literature to include trade openness, foreign direct investment, government expenditure, education, inflation, domestic investment, and foreign aid as control variables in the empirical model (Acheampong et al., 2021; Anderson et al., 2017; Bergh & Nilsson, 2010; Chong et al., 2009; Enowbi Batuo et al., 2015; Glomm & Ravikumar, 2003). The democracy indices were sourced from Coppedge et al. (2018) and income inequality data from Solt (2016) SWIID. The remaining variables were sourced from the World Development Indicators database. Except for the democracy indices, the remaining variables are transformed into natural logarithms for the estimation.

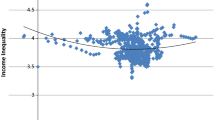

The simple bivariate correlation analysis suggests that the democracy indices positively correlate with income inequality (see Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) while natural resources negatively correlate with income inequality (see Fig. 6). The bivariate correlation analysis is not robust for us to generate inference about the effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality in SSA. Section 4 presents robust empirical results about the impact of democracy and natural resources on income inequality using advanced econometric techniques while accounting for the effect of trade openness, foreign direct investment, government expenditure, education, inflation, domestic investment, and foreign aid. The descriptive statistics and the variables descriptions are provided in Table 2.

4 Results and Discussions

In this section, we present and discuss the results of the study. Table 3 shows the estimates of the whole sample (SSA) based on the IV-GMM (models 1–5), the Lewbel 2SLS (models 6–10), and the Driscoll-Kraay (models 11–15) estimation methods. In all the estimations, the dependent variable is income inequality. The various models are distinguished by the five democracy variables used in the study (electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian).

The results show that the natural resource rent variable coefficient is positive in all the estimated models and across the estimation methods. The results imply that ceteris paribus, an increase in natural resource rent exerts an increasing effect on income inequality. Specifically, the results suggest that based on the IV-GMM estimations, a 1% increase in education could increase income inequality within the range of 0.035%-0.042% ceteris paribus. In the Lewbel 2SLS and the Driscoll-Kraay estimations, ceteris paribus, a 1% increase in natural resource rent could increase income inequality within the range of 0.031%-0.062% and 0.035%-0.041%, respectively. In essence, natural resource is a bane to income distribution in SSA, and the resource curse is apparent in the region.

Several studies have shown that SSA has not benefited much from natural resource rent, emphasizing an apparent existence of a resource curse in the region (see Dwumfour & Ntow-Gyamfi, 2018; Henry, 2019). A plausible explanation for the seeming resource curse may emanate from mismanagement that bedevils a number of spheres in the region. This has been occasioned by governments’ inability to manage resource rents sustainably (Adams et al., 2019; Mlambo, 2022). In their work, Atkinson and Hamilton (2003) explain that countries with natural resources where growth lags are those where the combination of natural resource, macroeconomic, and public expenditure policies have led to a low savings rate. This is plausibly the case of SSA, where the general populace may not benefit much from the natural resource rent that comes into their countries. One way the populace benefits from natural resource rent is by creating jobs from these rents (Ross, 2007). However, many governments in the region have failed to provide adequate jobs from the rents. Other factors that could explain the resource curse situation in SSA (in relation to its affecting income inequality) are corruption and perennial conflicts in many places where these resources are exploited (Frynas & Buur, 2020; Adhvaryu et al., 2018; Bruch et al., 2019). Our results largely buttress those of Bourguignon and Morrison (1990), Carmignani (2013), and Gylfason and Zoega (2002).

The democracy variables generally show positive coefficients (Table 3). Together, the democracy variables suggest that all other things being equal, an increase in democracy increases income inequality. Since democracy generally connotes “rule by the people,” one would expect the populace to generally benefit from democracy, which should influence their political, social and economic (including income distribution) exigencies. The story in a developing region like SSA might be different, as the region is experimenting with democracy. It has been argued in some circles that young democracies, like those in SSA, do not have the wherewithal (institutional framework and prowess) to enforce accountability, and as a result, the institutions fall prey to the dictates of a few political elites rather than meeting the interests of the general population (Gill et al., 2019). This corroborates the widely held notion that democracy in Africa benefits a few elites, especially the educated with political affiliations. In their work, Acemoglu et al. (2015) describe instances whereby the elites invest in de facto power and effectively capture state power devices. Acemoglu et al. (2015) also argue that democracy may transfer political power to the middle class instead of the poor, who form a chunk of the population, and if this happens, redistribution of income and reduction in inequality may only occur when the middle class is in support. The results may also be explained by corruption that channels enormous developmental resources into individual pockets. In SSA, many of the corrupt cases emanate from political arenas. It seems that democracy paves the way for some people to acquire political positions and affiliations to embezzle state resources. Many commentators have also emphasized that many politicians in Africa do not really have the interests of the masses at heart but their parochial interests. In many countries, political opponents oppose pro-poor policies by incumbent governments because these policies would increase the social capital of the incumbent government for re-election. In many instances, political opponents only come to the utmost consensus when passing legislation that benefits them directly, like salary and allowance increments.

Regarding the control variables, the education variable registers a statistically significant coefficient (at the 1% significance level) in all the estimated models across the three estimation methods. This implies that, all other things being equal, an increase in education worsens inequality in the SSA region. The results of the impact of education on income inequality run contrary to expectation, as education is considered important in promoting economic growth (Barro, 2013; Hanushek, 2013), which could likely reduce income inequality. However, the theoretical link between education and income inequality is unclear. For example, Knight and Sabot (1983) argue that the impact of education on income inequality can have two effects; “composition” and “wage compression” effects. With the expansion in education, income distribution favors the people with more education, and the ‘‘composition’’ effect posits that increasing education initially tends to raise income inequality. However, the supply of an educated labor force increases with increasing education, and the “wage compression” effect posits that this reduces the premium on education and hence lowers income inequality. Considering that education in SSA countries is relatively low and has only expanded in the last couple of decades, our results affirm the “composition” effect hypothesis. Getting employment and lucrative ones are skewed toward the few people with more education. SSA is also characterized by major disparities in educational attainment, and this exacerbates the income inequality situation (Turnovsky, 2011). In his model, Turnovsky (2011) shows that human capital (skilled labor resulting from education) is used more intensively in the human capital sector, increasing productivity and raising income inequality. Empirically, the results of this study buttress those of Acheampong et al. (2021) for SSA.

In all the estimated models and across all estimation methods, foreign aid is negatively and statistically significant at a 1% level (Table 3). The results suggest that increasing foreign aid significantly reduces income inequality ceteris paribus. Foreign aid is an injection of capital into the economy and, if used economically, can help governments alleviate inequality and poverty. In most SSA countries, annual budgets are largely supplemented by foreign aid. Hence, foreign aid serves as a significant component of government finances and expenditures. Some studies have also found that foreign aid correlates positively with economic growth (Asteriou, 2009; Karras, 2006), which in turn (is likely to) reduce income inequality. Some have, however, argued that foreign aid might only be a short to medium-term panacea to the woes of underdevelopment and that it is not a sustainable developmental anchor (Feeny, 2005; Sothan, 2018). Although this finding buttresses that of Alvi and Senbeta’s (2012) results, it contradicts those of Chong et al. (2009) and Herzer and Nunnenkamp’s (2012) findings.

The coefficient of the domestic investment (lngcf) variable enters negatively and is statistically significant. This indicates that, all other things being equal, an increase in domestic investment reduces income inequality. It is unsurprising that an increase in domestic investment reduces income inequality as domestic investment is considered an important source of growth and an effective instrument of job creation (Adams & Opoku, 2015). Also, the inflation variable is found to have negative and statistically significant coefficients in all the estimated models. This suggests that an increase in the general prices of goods and services reduces income inequality. This is quite counter-intuitive as inflation is generally expected to worsen inequality as it reduces the purchasing power of people, especially the poor. However, the effect of inflation on income inequality in the literature has been mixed, as some find inflation to be a regressive tax, others find it to be a progressive tax, while some find it to be unrelated to income distribution (Galli and Van Der Hoeven (2001). Galli and Van Der Hoeven (2001) showed that an increase in inflation could decrease and, at the same time, increase income inequality, which depends on the initial level of inflation. When initial inflation is high, decreasing inflation might decrease income inequality; when initial inflation is low, instead, reducing inflation might come at the cost of greater income inequality.

The government expenditure variable is found to have positive and statistically significant coefficients, suggesting that an increase in government expenditure increases income inequality ceteris paribus. Generally, one would expect an increase in government expenditure would reduce income inequality; however, this depends on whether it benefits the general population or supports pro-poor activities. Glomm and Ravikumar (2003) argue that the effectiveness of government expenditure on income distribution is ambiguous, as it depends on what the chunk of government spending is on. If a chunk of government expenditure goes into the military, it will not affect the populace much/directly. Corruption, which is common in SSA, could also bloat government expenditure, but the effect of the spending on the populace’s well-being may be minimal. Barro (1991) and Fischer (1991) also argue that an increase in government expenditure can negatively affect economic factors (including income distribution) through distortions emanating from taxation and crowding out of private investment. In SSA, governments usually borrow from both the domestic and foreign markets, and these loans are mainly serviced by taxation. An increase in taxation will reduce people’s real income and hence their purchasing power, exacerbating the income inequality situation that is prevalent in the region. Acheampong et al. (2021) found a similar outcome for the same region.

The effect of trade openness on income inequality is negative and statistically significant (except in models using Driscoll-Kraay, where it is largely statistically insignificant). The implication is that the openness of the economy to trade generally reduces income inequality. This is the case as trade generates vast employment opportunities for people, especially if the commodity traded involves intensive utilization of a factor in which a country is well endowed. Hence, when trade involves the services of a significant number of people in a country, including the poor, it provides a means of income for them, reducing income inequality. Our results bolster the findings of Dobson and Ramlogan-Dobson (2012) and Munir and Bukhari (2019). The foreign direct investment variable coefficients are statistically insignificant in all the estimated models (Table 3), indicating that foreign direct investment is not important in explaining variations in income inequality or income distribution in SSA. This may be explained because foreign direct investment flows to SSA mainly go to areas (mining and other natural resources exploitation) that employ just a handful of the populace. In many instances, the essential staff accompanying multinational corporations when they move to SSA are people from the origin countries. Hence, most people of the resource host region do not benefit directly from foreign direct investment inflows. Similarly, the results (Table 3) show that the coefficients of GDP (proxying economic growth) and its square are statistically insignificant; hence they do not explain income inequality. This is not surprising as, in the last couple of decades, economic growth rates have increased in lots of countries in the SSA region; however, this growth has not been accompanied by rising employment and incomes to a large extent. The implication is that economic growth in many of these countries is not driven by the majority poor and are hence not very much affected by it.

4.1 Does the Effect of Democracy and Natural Resources Differ among the Regions in SSA?

To account for the potential and obvious heterogeneity among countries in the SSA region, we perform a subsample analysis to ascertain whether the results differ. We disaggregate the full sample into the four sub-regions in SSA, namely, Central, Eastern, Southern, and West Africa. Table 4 shows the results for West Africa (models 1–5) and Eastern Africa (models 6–10). Table 5 shows the results for Central Africa (models 1–5) and Southern Africa (models 6–10).Footnote 3

Although natural resource is seen to increase income inequality for the full sample, the subsampling analyses show some disparities. Tables 3 and 4 show that the natural resources rent variable has negative and statistically significant coefficients for the West and Southern African subsamples. This suggests that for West and Southern Africa, an increase in natural resource rent is associated with a decrease in income inequality. Generally, countries in these subregions have been better able to leverage the rents from natural resources to reduce income inequality. For Eastern Africa, the coefficients of natural resources rent are still positive (and statistically significant), and they turn statistically insignificant (though still positive) for Central Africa. The effect of the democracy variables on income inequality for the subsamples largely remains the same (positive) as the full sample, except the coefficients turning statistically insignificant for the Eastern African sample (Tables 5 and 6).

Considering the control variables, the coefficients of trade openness enter negatively and statistically significant for West and Central African samples (Tables 5 and 6); these are results similar to those of the full sample (Table 3). This suggests that an increase in trade openness in these sub-regions could reduce income inequality. However, for the Eastern and Southern African samples, the coefficients are statistically insignificant, implying that trade openness does not significantly affect income inequality. As trade openness has the potential to increase job opportunities, it can also lead to job losses if an economy is import-dependent and is dumped with foreign goods. This can kill domestic industries, and the economy would not benefit much from trade openness.

Also, if what an economy trades in does not involve the services of a chunk of the people, the effect on income distribution may be minimal or insignificant. Similar to the full sample results, the effect of foreign direct investment is largely statistically insignificant for all the sub-regions except in the Central African sample, which shows that an increase in foreign direct investment is associated with a decrease in income inequality. Regarding the inflation variable, the results show that the negative coefficient registered by the full sample is most likely driven by the Eastern African sample. This is the case as the inflation coefficient is large and statistically insignificant (though negative) in all the subsamples except the Eastern African sample, where it is negative and statistically significant. Akin to the full sample results, the education variable is positive and statistically significant in all the subsamples (Tables 4 and 5), indicating that education increases the income inequality situation in all the sub-regions. Although for the full sample, an increase in government expenditure is found to increase income inequality, for the subsample, this situation is only found in West Africa. Government expenditure is found to have no effect in the Eastern African sample. In the Central and Southern African samples, an increase in education reduces income inequality.

Though the effect of economic growth on income inequality is statistically insignificant for the whole sample, the subsampling results indicate that an increase in economic growth (lngdpc) reduces income inequality in West and Central Africa (see Tables 4 and 5, respectively). This is the case as the coefficient of economic growth is negative and statistically significant. Also, the squared economic growth coefficient is positive and statistically significant for West and Central Africa. Contrary results are, however, found in Eastern and Southern Africa, where economic growth registers positive coefficients and economic growth squared negative coefficients. This implies that in Eastern and Southern Africa, an increase in economic growth increases income inequality; however, higher levels of economic growth tend to reduce inequality. The results of Eastern and Southern Africa buttress the Kuznets hypothesis’s theoretical underpinnings. The Kuznets hypothesis suggests that as economies develop and the level of economic growth increases, income inequality will first increase, then reach a maximum, and then fall after a certain income threshold (economic growth) is reached (Kuznets, 1955). The relationship between economic growth and income inequality exhibits an inverted “U-shaped” relationship for Eastern and Southern Africa. However, West and Central Africa’s results depict a rather “U-shaped” relationship where income inequality declines at the initial economic growth stage but rises after a certain threshold of economic growth (Tables 5 and 6).

The coefficient of foreign aid is only negative (and statistically significant) in the West African sample (Table 5), indicating that the West African sample drives the full sample results. In the Central African sample, it is found to be positive and statistically significant. For the other subsamples, it is statistically insignificant. Lastly, as a domestic investment generally increases income inequality in the West African sample, it reduces inequality in the Southern African sample. However, the coefficients of domestic investment are statistically insignificant in the Eastern and Central African samples.

4.2 Does Democracy Condition Natural Resources to Reduce Income Inequality in SSA?

Considering that income distribution and management of natural resource rents are largely political factors, we examine how democracy interacts with natural resource rent to affect income inequality in this subsection. Table 6 displays the results for the full sample, while Tables 7 and 8 show the results for the subsamples. Table 6 shows that the coefficients of the interactive term between all the democracy variables and natural resources are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. In addition, the net effect estimates based on Eq. (3) indicate that at the maximum value of electoral (0.840), liberal (0.730), participatory (0.545), deliberative (0.789), and egalitarian (0.698) democracies, natural resources increase income inequality by 0.051, 0.056, 0.057, 0.050 and 0.059 respectively. These results suggest that when democracy increases, natural resource rent worsens income inequality.

From the entire SSA sample, the interacting and net effect results imply that natural resources substantially drive income inequality in highly democratic countries. In other words, although natural resource rent worsens income inequality, this does not improve even if democracy increases. These results also demonstrate that in democratic countries, natural resources rent is associated with high-income inequality relative to more authoritarian countries. The fact that many countries in SSA are at the early stages of their democratic expedition may account for this. For many of these countries, democracy is under experimentation, and it has not gotten to the stage to reap the full benefits. This is unlike some advanced countries that have practiced democracy for centuries. Also, dispensing democracy comes at a huge cost for some SSA countries, and it is fraught with many challenges, including corruption. All these challenges aggravate the worsening effect of natural resource rent on income inequality. This contradicts Hartwell et al., (2019; page 532) hypothesis that “democratic institutions prevent extreme income polarization in a country blessed with natural resource endowments.” Thus, our interactive results contradict Hartwell et al.’s (2019) findings that democracy interacts with natural resources to reduce income inequality.

Comparatively, the results in Tables 7 and 8 show that the Eastern and Southern Africa subsamples exhibit similar interactive effects of natural resource rent and democracy on income inequality as the full sample; that is, in the presence of democracy increase in natural resource rent increases income inequality. However, the West and Central Africa subsamples show statistically insignificant interactive effects. In the West Africa region, the net effect results show that at the maximum value of electoral (0.792), liberal (0.710), participatory (0.489), deliberative (0.699), and egalitarian (0.644) democracies, natural resources significantly reduce income inequality by 0.039, 0.038, 0.046, 0.034 and 0.034 respectively. In the Eastern Africa region, the net effect estimate suggests that at the maximum value of electoral (0.840), liberal (0.730), participatory (0.545), deliberative (0.789), and egalitarian (0.698) democracies, natural resources significantly increase income inequality by 0.029, 0.031, 0.040, 0.032 and 0.052 respectively. Also, in the central Africa region, the net effect results show that at the maximum value of liberal (0.592), participatory (0.436), deliberative (0.559), and egalitarian (0.511) democracies, natural resources significantly reduce income inequality by 0.059, 0.044, 0.021 and 0.021 respectively. Finally, in Southern Africa, the net effect estimate suggests that at the maximum value of electoral (0.790), liberal (0.671), participatory (0.535), deliberative (0.695), natural resources insignificantly increase income inequality by 0.004, 0.005, 0.004, and 0.007 respectively while at the maximum value of egalitarian (0.549) democracy, natural resource insignificantly reduce income inequality by 0.002. These net effect results suggest that the effect of natural resources on income inequality conditioned by democracy differs among the SSA sub-regions.

5 Conclusion and Policy Implications

Prior studies have examined the effect of democracy or natural resources on income inequality. However, these studies have failed to account for how different democracy indices, such as electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian democracy, affect income inequality. We argue that using the disaggregated indicator of democracy would yield insightful results about the effect of democracy on income inequality. Another knowledge gap in the existing studies is that they have been silent on how democracy conditions natural resources to affect income inequality, especially in SSA. Examining the interactive effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality would help understand how natural resources in high-democratic countries affect income inequality. With these research gaps, this study adds to the literature by investigating the direct and indirect effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality using a comprehensive panel dataset for 43 SSA from 1990 to 2017. To present reliable conclusions and contribute to policy formulation, this study utilized instrumental variables techniques (IV-GMM and Lewbel TSLS) and Driscoll and Kraay estimator to estimate the effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality.

The findings from our empirical analysis are summarised in five (5) parts. First, the results indicated that democracy indices such as electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian democracy drive income inequality in SSA. Second, the findings also indicated that natural resources directly spur income inequality in SSA. Third, our regional analysis showed that democracy indices increase income inequality in West, Central, and Southern Africa while having a neutral effect on income inequality in Eastern Africa. The comparative analysis further showed that natural resources reduce income inequality in West and Southern African countries while increasing income inequality in Eastern Africa. In the case of Central Africa, natural resources play an insignificant role in income inequality. Fourth, the interactive effect analysis indicates that electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian democracy interacts with natural resources to increase income inequality, suggesting that in highly democratic countries, natural resources drive income inequality and vice versa. Finally, from the regional analysis, the democracy indices interacted with natural resources to increase income inequality in Eastern and Southern African countries while exerting an insignificant effect on income inequality in West and Central African countries.

From a theoretical and policy perspective, our findings add to the existing argument that democracy in SSA benefits a few elites, especially the educated with political affiliations. In SSA, democracy is expected to benefit poorer households by transferring political power from the high-income class to the lower-income groups, which comprise a significant proportion of the SSA population. However, congruent with Acemoglu et al.’s (2015) observation, democracy in SSA is rather transferring political power to the middle class instead of to the poor, which form a chunk of the population, and this has resulted in the widening of income disparity between wealthy households and the poorer households. In SSA, democracy paves the way for some people to acquire political positions and affiliations to amass wealth from state resources. Many commentators have emphasized that many politicians in SSA do not really have the interests of the masses at heart but their parochial interests. Our results call for democratic leaders in SSA to focus on formulating and implementing pro-poor policies that would increase economic opportunities for the poor and vulnerable people, enhancing their capability to function effectively in society rather than politicians passing legislation such as increasing allowances and salaries that benefit them directly.

Our study has also shown that natural resources have been associated with higher income inequality in SSA. One way of ensuring that natural resource rent positively affects income distribution is the creation of jobs from the rents (Ross, 2007). However, many governments in the SSA have failed to provide adequate employment from natural resources rent. Additionally, natural resources rent benefits the elite population with the political power to influence government policies at the expense of the poorer population. Our interactive effect analysis further substantiates this, highlighting that natural resources rent in highly democratic countries widens income inequality and vice versa. For this reason, governments in SSA need a distributive system that will ensure the effective utilization of resource rents for the benefit of all people, particularly those in the lower-income brackets.

This study contributes significantly to knowledge and policy; however, there a still some avenues for future research. Our study only examined the effect of democracy and natural resources on SSA and its subregions without probing further if the conclusion reached in this paper would differ between resource-rich and non-resource-rich countries. Future studies can comparatively examine the effect of democracy and natural resources on income inequality among resource-rich and non-resource-rich countries. Additionally, our study is limited to using an aggregate variable of natural resources; therefore, future studies can examine if the oil rent, mineral rent, and forest rent would affect income inequality differently. Finally, a future study can extend our approach and argument to different regions not considered in this study.

Notes

See Appendix Table 9 for countries included in this study.

Considering that the results are generally similar across the three estimation methods (IV-GMM, Lewbel 2SLS, Driscoll-Kraay) used, we employ the Driscoll-Kraay for the subsample estimations. The main reason for settling on Driscoll-Kraay is its ability to accommodate cross-sectional dependence, which is common with panel data.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2006). Modeling inefficient institutions. In: Blundell, R., Newey, W., Persson, T. (Eds.), Advances in Economic Theory. Proceedings of 2005 World Congress. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY.

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 47–100.

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2015). Democracy, redistribution, and inequality. In Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2, pp. 1885–1966). Elsevier.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). Persistence of power, elites, and institutions. American Economic Review, 98(1), 267–293.

Acheampong, A. O., Dzator, J., & Shahbaz, M. (2021). Empowering the powerless: Does access to energy improve income inequality? Energy Economics, 99, 105288.

Adams, D., Ullah, S., Akhtar, P., Adams, K., & Saidi, S. (2019). The role of country-level institutional factors in escaping the natural resource curse: Insights from Ghana. Resources Policy, 61, 433–440.

Adams, S., & Opoku, E. E. O. (2015). Foreign direct investment, regulations and growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy, 47, 48–56.

Adhvaryu, A., Fenske, J. E., Khanna, G., & Nyshadham, A. (2018). Resources, conflict, and economic development in Africa (No. w24309). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ahmadov, A. K. (2014). Oil, democracy, and context: A meta-analysis. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1238–1267.

Alesina, A., Glaeser, E., & Glaeser, E. L. (2004). Fighting poverty in the US and Europe: A world of difference. Oxford University Press.

Alvarado, R., Tillaguango, B., López-Sánchez, M., Ponce, P., & Işık, C. (2021). Heterogeneous impact of natural resources on income inequality: The role of the shadow economy and human capital index. Economic Analysis and Policy, 69, 690–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2021.01.015

Alvi, E., & Senbeta, A. (2012). Does foreign aid reduce poverty? Journal of International Development, 24(8), 955–976.

Anderson, E., Jalles D’Orey, M. A., Duvendack, M., & Esposito, L. (2017). Does government spending affect income inequality? A meta-regression analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys, 31(4), 961–987.

Anderson, J. E., & Yotov, Y. V. (2016). Terms of trade and global efficiency effects of free trade agreements, 1990–2002. Journal of International Economics, 99, 279–298.

Anyanwu, U. M., Anyanwu, A. A., & Cieślik, A. (2021). Does abundant natural resources amplify the negative impact of income inequality on economic growth? Resources Policy, 74, 102229.

Arezki, R., & Gylfason, T. (2013). Resource rents, democracy, corruption and conflict: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Economies, 22(4), 552–569.

Asif, M., Khan, K. B., Anser, M. K., Nassani, A. A., Abro, M. M. Q., & Zaman, K. (2020). Dynamic interaction between financial development and natural resources: Evaluating the ‘resource curse’hypothesis. Resources Policy, 65, 101566.

Asongu, S. A., Le Roux, S., & Biekpe, N. (2017). Environmental degradation, ICT and inclusive development in sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Policy, 111(December), 353–361.

Asteriou, D. (2009). Foreign aid and economic growth: New evidence from a panel data approach for five South Asian countries. Journal of Policy Modeling, 31(1), 155–161.

Atkinson, G., & Hamilton, K. (2003). Savings, growth and the resource curse hypothesis. World Development, 31(11), 1793–1807.

Auty, R. (2002). Sustaining development in mineral economies: The resource curse thesis. Routledge.

Awoa, P. A., Ondoa, H. A., & Tabi, H. N. (2022). Women’s political empowerment and natural resource curse in developing countries. Resources Policy, 75, 102442.

Azfar, O., Kahkonen, S., Lanyi, A., Meagher, P., & Rutherford, D. (2018). Decentralization, governance and public services: the impact of institutional arrangements. In Devolution and development (pp. 45–88). Routledge.

Badeeb, R. A., Lean, H. H., & Clark, J. (2017). The evolution of the natural resource curse thesis: A critical literature survey. Resources Policy, 51, 123–134.

Bahamonde, H., & Trasberg, M. (2021). Inclusive institutions, unequal outcomes: Democracy, state capacity, and income inequality. European Journal of Political Economy, 70, 102048.

Balcázar, C. F. (2016). Long-run effects of democracy on income inequality in Latin America. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 14(3), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-016-9329-3

Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 407–443.

Barro, R. J. (2013). Inflation and economic growth. Annals of Economics and Finance, 14(1), 301–328.

Baum, C. F., Schaer, M. E., & Stillman, S. (2002). Instrumental variables and GMM: Estimation and testing. Working Paper. Boston College Economics.

Bearce, D. H., & Laks Hutnick, J. A. (2011). Toward an alternative explanation for the resource curse: Natural resources, immigration, and democratisation. Comparative Political Studies, 44(6), 689–718.

Bergh, A., & Nilsson, T. (2010). Do liberalisation and globalisation increase income inequality? European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 488–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.03.002

Bergougui, B., & Murshed, S. M. (2020). New evidence on the oil-democracy nexus utilising the varieties of democracy data. Resources Policy, 69, 101905.

Bhattacharyya, S., & Hodler, R. (2010). Natural resources, democracy and corruption. European Economic Review, 54(4), 608–621.

Bourguignon, F., & Morrisson, C. (1990). Income distribution, development and foreign trade: A cross-sectional analysis∗. European Economic Review, 34(6), 1113–1132.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. M., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82.

Brooks, S. M., & Kurtz, M. J. (2022). Oil “rents” and political development: What do we really know about the curse of natural resources? Comparative Political Studies, 55(10), 1698–1731.

Bruch, C., Jensen, D., Nakayama, M., & Unruh, J. (2019). The changing nature of conflict, peacebuilding, and environmental cooperation. Envtl. L. Rep. News and Analysis, 49, 10134.

Brueckner, M., & Lederman, D. (2018). Inequality and economic growth: The role of initial income: The World Bank.

Brunnschweiler, C. N. (2008). Cursing the blessings? Natural resource abundance, institutions, and economic growth. World Development, 36(3), 399–419.

Carmignani, F. (2013). Development outcomes, resource abundance, and the transmission through inequality. Resource and Energy Economics, 35(3), 412–428.

Caselli, F., & Tesei, A. (2016). Resource windfalls, political regimes, and political stability. Review of Economics and Statistics, 98(3), 573–590.

Chekouri, S. M., Chibi, A., & Benbouziane, M. (2017). Algeria and the natural resource curse: Oil abundance and economic growth. Middle East Development Journal, 9(2), 233–255.

Chong, A., Gradstein, M., & Calderon, C. (2009). Can foreign aid reduce income inequality and poverty? Public Choice, 140(1), 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9412-4

Cockx, L., & Francken, N. (2016). Natural resources: A curse on education spending? Energy Policy, 92, 394–408.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, S., Hicken, A., et al. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: A new approach. Perspectives on Politics, 9(2), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711000880

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Lindberg, S. I., Skaaning, S.-E., Teorell, J., Altman, D., et al. (2018). V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v8. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Davarzani, F. (2022). The impact of income inequality on domestic investment in resource-rich countries.

Dinye, R. D., & Erdiaw-Kwasie, M. O. (2012). Gender and labour force inequality in small-scale gold mining in Ghana. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 4(10), 285–295.

Dobson, S., & Ramlogan-Dobson, C. (2012). Why is corruption less harmful to income inequality in Latin America? World Development, 40(8), 1534–1545.

Driscoll, J. C., & Kraay, A. C. (1998). Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(4), 549–560.

Dwumfour, R. A., & Ntow-Gyamfi, M. (2018). Natural resources, financial development and institutional quality in Africa: Is there a resource curse? Resources Policy, 59, 411–426.

Ebeke, C. H., & Etoundi, S. M. N. (2017). The effects of natural resources on urbanisation, concentration, and living standards in Africa. World Development, 96, 408–417.

Enowbi Batuo, M., Esfandiar Maasoumi, P. A. P., & Asongu, S. A. (2015). The impact of liberalisation policies on income inequality in African countries. Journal of Economic Studies, 42(1), 68–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/jes-05-2013-0065

Epo, B. N., & Nochi Faha, D. R. (2020). Natural resources, institutional quality, and economic growth: An African tale. The European Journal of Development Research, 32(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-019-00222-6

Erdoğan, S., Yıldırım, D. Ç., & Gedikli, A. (2020). Natural resource abundance, financial development and economic growth: An investigation on Next-11 countries. Resources Policy, 65, 101559.

Farhadi, M., Islam, M. R., & Moslehi, S. (2015). Economic freedom and productivity growth in resource-rich economies. World Development, 72, 109–126.

Feeny, S. (2005). The impact of foreign aid on economic growth in Papua New Guinea. Journal of Development Studies, 41(6), 1092–1117.

Fernandez, V. (2021). Copper mining in Chile and its regional employment linkages. Resources Policy, 70, 101173.

Fischer, S. (1991). Growth, macroeconomics, and development. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 6, 329–364.

Frankel, J. A. (2010). The natural resource curse: a survey (No. w15836). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Frynas, J. G., & Buur, L. (2020). The resource curse in Africa: Economic and political effects of anticipating natural resource revenues. The Extractive Industries and Society, 7(4), 1257–1270.

Frynas, J. G., Wood, G., & Hinks, T. (2017). The resource curse without natural resources: Expectations of resource booms and their impact. African Affairs, 116(463), 233–260.

Galli, R. & Van Der Hoeven, R. (2001), Is inflation bad for income inequality? The importance of the initial rate of inflation, Geneva employment sector, International labour organization (ILO) employment working paper no. 29, Geneva.

Gavin, M., & Hausmann, R. (1998). Nature, development and distribution in Latin America: evidence on the role of geography, climate and natural resources. IADB, Research department working paper, (378).

Gelb, A. H. (1988). Oil windfalls: Blessing or curse? Oxford University Press.

Gill, A. R., Hassan, S., & Viswanathan, K. K. (2019). Is democracy enough to get early turn of the environmental Kuznets curve in ASEAN countries? Energy and Environment, 30(8), 1491–1505.

Glomm, G., & Ravikumar, B. (2003). Public education and income inequality. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(2), 289–300.

Goderis, B., & Malone, S. W. (2011). Natural resource booms and inequality: theory and evidence. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(2), 388–417.

Gradstein, M., Milanovic, B., & Ying, Y. (2001). Democracy and Income Inequality: An Empirical Analysis. Policy Research Working Paper; No. 2561. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/19685. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Gyimah-Boadi, E., & Prempeh, H. K. (2012). Oil, politics, and Ghana’s democracy. Journal of democracy, 23(3), 94–108.

Gylfason, T. (2001). Natural resources, education, and economic development. European Economic Review, 45(4–6), 847–859.

Gylfason, T., & Zoega, G. (2003). Inequality and economic growth: Do natural resources matter? Inequality and Growth: Theory and Policy Implications, 1, 255.

Hanushek, E. A. (2013). Economic growth in developing countries: The role of human capital. Economics of Education Review, 37, 204–212.

Hartwell, C. A., Horvath, R., Horvathova, E., & Popova, O. (2019). Democratic institutions, natural resources, and income inequality. Comparative Economic Studies, 61(4), 531–550. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-019-00102-2

Haseeb, M., Kot, S., Iqbal Hussain, H., & Kamarudin, F. (2021). The natural resources curse-economic growth hypotheses: Quantile–on–quantile evidence from top Asian economies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279, 123596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123596

Havranek, T., Horvath, R., & Zeynalov, A. (2016). Natural resources and economic growth: A meta-analysis. World Development, 88, 134–151.

Hayat, A., & Tahir, M. (2021). Foreign direct investment, natural resources and economic growth: A threshold model approach. Journal of Economic Studies, 48(5), 929–944. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-03-2020-0127

Henry, A. (2019). Transmission channels of the resource curse in Africa: A time perspective. Economic Modelling, 82, 13–20.

Herzer, D., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2012). The effect of foreign aid on income inequality: Evidence from panel cointegration. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 23(3), 245–255.

Hoechle, D. (2007). Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. The Stata Journal, 7(3), 281–312.

Hodler, R. (2006). The curse of natural resources in fractionalised countries. European Economic Review, 50(6), 1367–1386.

Humphreys, M., Sachs, J. D., Stiglitz, J. E., Humphreys, M., & Soros, G. (2007). Escaping the resource curse. Columbia University Press.

Hussain, M., Ye, Z., Bashir, A., Chaudhry, N. I., & Zhao, Y. (2021). A nexus of natural resource rents, institutional quality, human capital, and financial development in resource-rich high-income economies. Resources Policy, 74, 102259.

Jauch, S., & Watzka, S. (2016). Financial development and income inequality: A panel data approach. Empirical Economics, 51(1), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-1008-x

Karras, G. (2006). Foreign aid and long-run economic growth: Empirical evidence for a panel of developing countries. Journal of International Development: THe Journal of the Development Studies Association, 18(1), 15–28.

Khan, A. A., Luo, J., Safi, A., Khan, S. U., & Ali, M. A. S. (2022). What determines volatility in natural resources? Evaluating the role of political risk index. Resources Policy, 75, 102540.

Kim, D.-H., Chen, T.-C., & Lin, S.-C. (2020). Does oil drive income inequality? New panel evidence. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 55, 137–152.

Kim, D. H., & Lin, S. C. (2018). Oil abundance and income inequality. Environmental and Resource Economics, 71, 825–848.

Knight, J. B., & Sabot, R. H. (1983). Educational expansion and the Kuznets effect. The American Economic Review, 73(5), 1132–1136.

Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2009). Is transparency the key to reducing corruption in resource-rich countries? World Development, 37(3), 521–532.

Kopiński, D., Polus, A., & Tycholiz, W. (2013). Resource curse or resource disease? Oil in Ghana. African Affairs, 112(449), 583–601.

Kordbacheh, H., & Sadati, S. Z. (2022). Corruption and banking soundness: Does natural resource dependency matter? Journal of Financial Crime, 29(1), 293–308.

Kuznets, S. (1955). Economic growth and income inequality. The American Economic Review, 45(1), 1–28.

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy1. American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69–105.

Leamer, E. E., Maul, H., Rodriguez, S., & Schott, P. K. (1999). Does natural resource abundance increase Latin American income inequality? Journal of Development Economics, 59(1), 3–42.

Lessmann, C., & Steinkraus, A. (2019). The geography of natural resources, ethnic inequality and civil conflicts. European Journal of Political Economy, 59, 33–51.

Lewbel, A. (2012). Using heteroscedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasured and endogenous regressor models. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 30(1), 67–80.

Mehlum, H., Moene, K., & Torvik, R. (2006). Institutions and the resource curse. The Economic Journal, 116(508), 1–20.