Abstract

Recent studies suggest that South Africa has experienced increased income polarization and is dealing with a struggling middle class. However, with some studies reporting a strong middling tendency, there seems to be a large discrepancy between how people perceive their social position and their actual economic status. Surprisingly, even with the most unequal society label, South Africa has received little attention on the dynamics behind how people perceive their social status. This study uses an ordered probit regression to analyze the determinants of individuals’ subjective social status in South Africa. Results show that objective factors, education, and occupation status positively influence subjective social status. However, subjective social mobility and class imagery are as crucial, confirming the multidimensionality behind subjective social status. Given the high-income polarization and racial inequality in South Africa, the study also showed that factors driving subjective social status are heterogeneous for different race and income groups. The results confirm this and find that discrepant objective and subjective factors influence different populations’ and income groups’ subjective social status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This article explores the determinants behind subjective social status in a highly unequal setting. The country of South Africa is regarded as the most unequal society in the world, with high-income polarization and racial inequality dominating policy discussions (Francis & Webster, 2019; Schotte et al., 2018). While objective inequality has received much research attention, little is known about the dynamics behind subjective social status in this highly unequal setting. Previous studies in South Africa point to a strong middling tendency among individuals when placing themselves in society (Burger et al., 2015; Kirsten et al., 2022), an attribution that vastly contradicts the high objective inequality led by income polarization and a struggling middle class. In this case, understanding the drivers behind perceived social placement is particularly important.

South Africa also has unprecedented racial inequality and extended periods of colonialism and apartheid regimes. Historically, most production factors have been in the hands of a few (mostly white) individuals, while other population groups had to settle as dependent low-skilled laborers. Not only have these discriminating regimes driven racial class wedges in South Africa, but it has also influenced the subjective social status of individuals from the different social groups. Herein lies a vital contribution of this study: analyze the factors influencing individuals’ subjective social status in South Africa. Specifically, it investigates how determinants of subjective social status may vary by population sub-group and income group. This line of inquiry is particularly important for policymakers since policy responses (based on specific determinants of subjective social status) may not affect all sub-population groups or income groups in the same way.

The rest of the paper is structured with a detailed assessment of the theoretical background for subjective social status. After that, sections three and four cover the descriptive and empirical analysis of the dynamics behind perceived social status in South Africa.

2 Literature Review

There is an ongoing debate about what drives subjective social status (Kim & Lee, 2021). While objective factors like income, occupation, and education play a vital role, they do not fully account for how individuals perceive their societal position, and many studies have referred to the multidimensional nature of how individuals perceive their social rank (Andersen & Curtis, 2012; Evans & Kelley, 2004; Evans et al., 1992; Goldman et al., 2006; Haddon, 2015; Hout, 2008; Lindemann & Saar, 2014). For example, some studies show that class imagery, that is, the view individuals have of the class structures, influences perceived social status (Evans et al., 1992, 2013; Oddsson, 2018). At the same time, other studies show that perceived intergenerational mobility strongly influences individuals’ social position (Gugushvili, 2020; Kelley & Kelley, 2009). In particular, these subjective factors are linked under a similar decision-making process, further explaining the multidimensional process behind how people see themselves in society (Kim & Lee, 2021).

Popular support for this multidimensionality is a strong middling tendency, where most people tend to choose the middle of the social stratum when placing themselves in society, regardless of their economic position (Chen & Fan, 2015; Evans & Kelley, 2004; Sudo, 2019). Highly linked with the reference theory (Merton, 1968), people tend to compare themselves to individuals around them with similar life conditions, normally consisting of family, friends and co-workers from the same social class. This type of reference group homogeneity leads to a middling tendency mainly driven by perceived equal status within the homogenous reference groups or people’s under or overestimated social positions because of the comparison with those they perceive above or below them. For example, a family doctor might see specialists and Nobel laureates in the medical field above himself/herself; the doctor would then underestimate their societal position and place themselves towards the middle of society. While a unskilled factory worker might perceive himself/herself above those around them who are struggling for a steady job and would therefore overestimate their position, placing themselves in the middle of society (Evans & Kelley, 2004). This homogeneity within reference groups could provide an incomplete frame of society, further creating distance between subjective self and objective factors. We aim to further this literature and contribute to the yet relatively unexplored research field around the dynamics behind subjective social status in a highly unequal setting. Since South Africa is struggling with extreme levels of income and racial inequality yet has a strong middling tendency, it presents a captivating dilemma of perceptions versus reality in the most unequal society in the world.

Only a handful of studies have assessed the determinants behind subjective social status in the South African context. For example, Posel and Casale (2011) descriptively found, using the National Income Dynamic Study (NIDS) data, that perceived social positions differ significantly from objective factors. For those who rank among the wealthiest quintile in South Africa, only 6% self-identify among the richest, while 63% identified in the middle and 32% positioned themselves in the lower class. Those in the middle third income quintile mostly see themselves as poor (58%), while the rest see themselves in the middle. Posel and Casale (2011) also show that those in the bottom third of the income quintile have the highest correlation between objective and subjective class positions, with 69% of the bottom income group placing themselves in the lowest societal positions.

Furthermore, a study by Seekings (2007), using regional data for Cape Town, found a clear but inexact relationship between objective and subjective class schemes, finding neighborhood incomes, mediated class positions, and race all play a vital role in causing variation between objective and subjective social positioning. Seekings (2007) shows Africans are far more likely to report they belong to the lower class, while Coloureds tend to identify in the working class and Whites predominantly in the middle class. Similarly, using NIDS panel data for South Africa, Burger et al. (2015) showed there is still a large gap between subjective and objective class measures, especially for the black middle class. The end of apartheid was marked by the emergence of a new black middle class that has grown consistently over the last two decades. However, very few of these individuals place themselves in the middle class due to the reluctance to self-identify in the predominantly White middle class. Therefore, the racial and income impact on the discrepancy between objective factors and subjective social status needs further assessment.

However, the studies mentioned above (Seekings, 2007; Posel & Casale, 2011; Burger et al., 2015) are mainly based on unrepresentative samples of specific demographic groups or certain cities or do not provide a detailed assessment of the determinants behind subjective social status for the South African population. Thus, these findings are insufficient to identify a holistic view of subjective social status in a South African society still suffering from high racial and income inequalities (Bhorat et al., 2019; Leibbrandt et al., 2010, 2012).

This study aims to add value to this research field and, in detail, assess the determinants behind subjective social status in South Africa while furthering the discussion by assessing how people from different races and income groups determine their subjective social status. By using the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) Social Inequality dataset, a dataset rarely used in South African literature, we attempt to provide a holistic view of subjective social status dynamics. Understanding the dynamics of what drives people’s perceived status in a highly unequal society should provide insights into how people from different race and income groups view their subjective social status. This study could help policymakers understand the dynamics behind subjective social status in a diverse and unequal society and provide vital information about perceived social rank among South Africans belonging to different social groups.

3 Data and Methodology

3.1 Data

The study uses the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) dataset. The ISSP Social Inequality series is a multi-national survey conducted in various countries, including South Africa. The ISSP dataset is one of the most comprehensive to study individuals’ perceptions about various social structures and includes information about individuals’ subjective social positions, social policy perceptions, redistribution preferences, intergenerational mobility, fairness, and inequality perceptions (ISSP Research Group, 2017; Kuhn, 2019). The survey, however, is only available for 2009 in South Africa. The 2009 ISSP survey consists of 3502 households and captures a wide range of individual and household-level data representing the South African population. The following section describes the variables used in the study.

3.1.1 Subjective Social Status

The dependent variable in the study is individuals’ subjective social status, measured using the ISSP question that states: In your society, there are groups that tend towards the top and groups that tend to be towards the bottom. Below is a scale that runs from top to bottom. Where would you put yourself now on this scale? (ISSP Research Group, 2017). For regression purposes, scores ranging from 0 to 100 are assigned for the ten-step ladder question (Evans & Kelley, 2004). This ten-step ladder question has been a highly used measure of subjective social status (Adler et al., 2000; Goldman et al., 2006; Ostrove et al., 2000; Singh-Manoux et al., 2003).

3.1.2 Objective Factors

Objective factors are the most significant determinants of where people see themselves (Evans & Kelley, 2004; Goldman et al., 2006; Haddon, 2015; Oddsson, 2018). This study includes income, education, and occupation status as measures of economic status. The household income measure is motivated by heavy income polarization (Visagie & Posel, 2013).Footnote 1 Empirical studies show that, since 1994, the welfare of the middle class has declined, suffering from low wage growth, stagnated education levels, and automation of semi-skilled jobs (Bhorat et al., 2019). The study by Bhorat et al. (2019) refers to this struggling middle-income group as households falling between the 30th and 70th percentiles. The study similarly uses the middle 40 percentile as a reference middle measure for the income group classification, with those in the bottom and top 30 percentiles making up the lower and upper-income groups. Education is a categorical variable separated into three groups, primary education or less, upper secondary education, and university education. While occupation level is grouped into three separate groups: those who are low-skilled, semi-skilled, and skilled occupations.Footnote 2 Given the strong possibility that different race and income groups could influence the relationship between objective and subjective social status, the model also includes interaction terms. These include an interaction term between race and occupation, race and education, income group and occupation, and income group and education.

3.1.3 Class Imagery

Given the multidimensionality behind subjective social status, the study also includes other subjective factors. Class imagery is measured using the ISSP survey question, asking individuals to choose between five diagrams on how they would view the social structure in their country. The literature can also support a graphical demonstration to measure class imagery (Castillo, 2011; Oddsson, 2018). Individuals can choose between five diagrams on how they perceive South African society (refer to Fig. 1). Individuals who chose type A believe that most of society is at the bottom, very few at the top, and almost no one in the middle.

Similarly, individuals who view society as type A also perceive inequality as too high. As individuals move from type A to type E, they view more people in the middle and top positions and less at the bottom, perceiving less social inequality. In terms of the scoring system used, the study conducted preliminary analysis on both the Likert equal interval scoring (0, 25, 50, 75, and 100) and the unequal intervals as proposed by Evans et al. (1992) and Evans and Kelley (2004).Footnote 3 Using both the Likert and unequal intervals led to similar results. The study uses the most conventional measure—the Likert equal interval scoring.

3.1.4 Subjective Social Mobility

Subjective social mobility relates to how individuals perceive their social status compared to their parents. It is measured using the ISSP survey, as respondents compare their current job status to that of their fathers when they were teenagers (Kelley & Kelley, 2009). In the ISSP Social Inequality survey, the question stated, please think about your present job (or your last one if you don’t have one now). If you compare this job to the job your father had when you were < 14/15/16 > , would you say that the level of status of your job is (or was). Respondents are then provided with five response options that include (1) much higher than your father’s, (2) higher, (3) about equal, (4) lower, and (5) much lower than your father’s. These scores were then recorded, so downward mobility took the lowest scores (1 and 2), while those that were immobile scored in the middle (3), and those who experienced upward mobility had the highest scores (4 and 5). The five categories were then assigned scores from 0 to 100 for descriptive purposes and are consistent with the literature (Kelley & Kelley, 2009). In order to further assess the nature of the subjective social mobility measure, a categorical variable for perceived mobility was created, taking the value of upward, downward, or no mobility. The categorical variable was used to determine the separate impact of upward and downward perceived mobility on subjective social status, while no perceived mobility was used as the reference category.

3.1.5 Control Variables

Consistent with the literature, gender (Yamaguchi & Wang, 2002), age (Lindemann, 2007; Oddsson, 2018), and race (Shaked et al., 2016) were also used in the study to determine the factors behind subjective social status. Table 1 summarises all the variables used in this study.

3.2 Methodology

This study used an ordered probit model to examine the determinants of subjective social status. An ordered probit model is motivated by the possibility that the social strata do not represent equal intervals on a given social hierarchy (Greene, 1991). The ordered probit model is also the best-fit model when the dependent variable is ordinal, as with the subjective social status variable. The model is expressed as follows:

where \(\gamma_{i}^{*}\) is the ordinal latent variable, \(x_{i}\) a vector of explanatory variables, \(\beta\) and the vector of unknown parameters and \(\varepsilon_{i}\) is the randomly distributed error term. The number of outcomes is represented by \(j\), and this case sums up to 10. The different cut-off points are shown by \(\alpha_{j - 1}\) and \(\alpha_{j}\). Various studies have reported similar findings using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method (Evans & Kelley, 2004; Knell & Stix, 2017). This study, therefore, also used OLS regression as a robustness check to confirm underlying results (results available upon request). Furthermore, studies show that using the ordered probit model could violate the parallel-line assumption. The Likelihood Ratio (LR) test popularised by Wolf and Gould (1998) and Long and Freese (2006) was used to test this assumption. The results for the LR test indicate that the parallel assumption is violated, and further measures need to be put in place. There are various ways to account for the violation of the parallel line assumption. A generalized ordered probit model can account for this violation (Williams & Quiroz, 2019). However, as Mahmood et al. (2019) indicated, the generalized ordered probit model is susceptible to low-frequency datasets where low-frequency counts in the ordinal dependent variable make it challenging to use the generalized ordered probit model. Due to the low frequency in this paper, similar to Mahmood et al. (2019), the study uses the multinomial model to account for possible violations of the parallel line assumption. Results for the multinomial model can be found in the appendix.Footnote 4

4 Descriptive Analysis and Empirical Results

Table 2 shows the distribution of subjective social status by different social groups. There is a sample-size discrepancy within the table due to an absence of responses for some variables. For example, education and occupation had 20 and 206 missing values because respondents did not know, refused to answer, or marked the question as not applicable. There were 86 missing values for the work-status variable due to the exclusion of the option of other reasons for not being in the labor force (like temporarily sick) and some respondents refusing to answer the work-status question. Furthermore, subjective social mobility had 1261 missing values due to a significant number of respondents indicating that they have never had a job or never knew what their father did, while some indicated they do not know how to answer the question. In line with the literature, respondents who could not identify their perceived social mobility were removed from the analysis (Engelhardt & Wagener, 2014; Kelley & Kelley, 2009). Lastly, there were 83 respondents for whom the class imagery questions were not applicable, or they could not choose.

Observing subjective social status in Table 2, consistent with most of the literature on subjective status analysis, there is a middling tendency when individuals self-select their status in society (Evans & Kelley, 2004; Evans et al., 1992; Posel & Casale, 2011). For example, within South Africa, 64% of individuals chose a middle to the higher middle position in society (rung 4 to 7). Looking at gender differences, surprisingly, there is no difference between males’ and females’ subjective social status. For the geographical location, individuals living in rural households tend to choose lower societal positions than urban-dwelling individuals. Table 2 also reports the relationship between subjective social status and objective economic outcomes. For example, the more educated an individual is, the higher their subjective social status. The positive correlation with subjective social status is also the case for different occupational skill levels, with semi-skilled and skilled individuals choosing a higher position than a low-skilled individuals. These initial findings confirm the blended model used by Evans and Kelley (2004), while even with the marked tendency for choosing a middle position, economic objective factors still lead to variation within the choice of perceived social status.

Observing the relationship between subjective social status and other subjective factors yields some interesting primary findings. It is expected that subjective social mobility should positively influence subjective social status. A perceived positive relationship between subjective social status and subjective social mobility confirms this. We find almost no movement in class imagery as individuals perceive an unequal society. Therefore, the middling tendency dominates even with different perceived class imagery levels. The initial findings are not yet enough to indicate how these subjective factors influence individuals’ subjective social status, and additional empirical analysis needs to be conducted to make better sense of these initial findings.

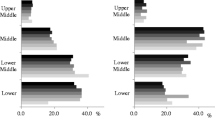

This paper also aims to decompile the determinants of subjective social status by race and income groups in a South African context. Figures 2 and 3 show individuals’ positions decompiled by these groups. Looking at the subjective social status by race, one can observe a bottom-heavy middling status for Africans and Coloureds, and a top-heavy middling status for the White and Indian population. For example, Africans tend to see themselves in the lower or middle position in society, with a small amount at the top. The same can be seen with the Coloured population. This is different from the White population, where a majority would see themselves at the middle to top of society, and only a few would see themselves on the lower rungs. Similarly, for Indians, we observe more people placing themselves on the top or middle positions, with only a small amount at the bottom. However, there is still a middling tendency for all race groups, and these findings align with the literature (Seekings, 2007; Posel & Casale, 2011).

Figure 3 reports the subjective social status of households in different household income percentiles. In this study, the population is divided into three income groups, namely, the bottom 30% (percentile 0–30), the middle 40% (percentile 30–70), and the top 30% (percentile 70–100). Using this classification, Fig. 3 clearly shows that individuals in the middle of the income distribution view themselves on higher steps than individuals in the bottom 30% but on lower steps than those within the top 30%. These preliminary results indicate that income does play a role in determining society’s subjective status, as confirmed by most prior empirical studies (Haddon, 2015; Lindemann & Saar, 2014; Oddsson, 2018). Furthermore, the same income classification was used in the regression results.

5 Empirical Results

The following section deals with the empirical analysis of this paper. The section first shows the ordered probit model results for the full sample. The study further decompiles the model for different race and income groups.

Table 3 reports the stepwise regression results for the full sample ordered probit model. Firstly, observing the impact of objective factors like occupation and education shows that both are positive and significant determinants of subjective social status. For example, individuals with semi- and high-skilled occupations tend to perceive themselves higher up the social ladder than those with low-skilled jobs. Secondary or university education was associated with higher subjective social status levels than primary education. These findings are in line with the international literature on the objective predictors of subjective social status (Evans & Kelley, 2004; Hout, 2008; Singh-Manoux et al., 2003), and confirm that even with a strong middling tendency among South Africans, the significance of objective factors driving subjective social status.

Furthermore, Model 1 also adds control variables, age and gender. The results show that gender does not influence subjective social status, and age is positive and significant in the first two models but insignificant in the third and final model. With the high levels of youth unemployment and gender inequality, it is expected that gender and age are negatively related to individuals’ subjective social status. However, this is not the case, and being female or young does not tend to influence individuals’ subjective social status in South Africa. This might be explained by Seekings and Nattrass (2008), who show that individuals base their social status on other members’ status in the household. For instance, unemployed youth or stay-at-home mothers could have someone in the family working; thus, they see themselves as higher than their actual economic position. These findings contrast with international studies (Haddon, 2015; Lindemann & Saar, 2014) and point to the unique nature of the dynamics behind people in South Africa choosing certain societal positions.

Since South Africans still have a strong middling tendency, objective factors might not explain all the variation between subjective social status. Model 2 includes additional subjective factors to determine the significance of subjective social mobility and class imagery in the perceived social status model. The results show that subjective social mobility is a positive and significant determinant of subjective social status (consistent with findings from Kelley & Kelley, 2009). However, the relationship between perceived mobility and subjective social status needs to be further assessed, explicitly assessing the separate impact of upward and downward mobility perceptions on subjective social status. This is done by using a categorical perceived mobility variable that takes the value of either upward, downward, or no perceived mobility and is included in the regression model (results in the appendix). The results show that while the subjective social status of those who perceive downward mobility is statistically different from those with no mobility (the reference category), the upward perceived mobility variable is insignificant. Those who perceive upward mobility do not see themselves on higher social steps than those who perceive no mobility. This indicates that subjective social status is more sensitive for those who perceive they have moved down the social ladder, making the relationship between subjective social status and perceived mobility downward dominant. This could be explained by the stratification dynamics in South Africa, with extreme levels of poverty and a struggling middle class (Bhorat et al., 2019; Schotte et al., 2018). Those who moved down the social ladder or perceived they moved down the social ladder are mainly people at the lower end of the income distribution, and this downward movement negatively influences their perceived social status.Footnote 5 Also, given the increasing inequality between those at the top and middle of the income distribution, those at the top have moved further up the social ladder. This movement might not have led them to perceive higher mobility since their parents were already on high social steps, possibly explaining some of the similarities of social status between those who perceive upward mobility and those who perceive no mobility. Furthermore, class imagery is, as expected, negative and significant, meaning people who view the class structure as more inegalitarian (unequal) would choose a lower position in society. These findings align with Evans et al. (2013) and Oddsson (2018).

Overall, model 1 and 2 confirms the significance of objective and subjective factors driving perceived social status among South Africans, reaffirming the multidimensionality behind subjective social status. It should also be noted that, as we add these subjective indicators to the model, the semi-skilled occupation variable becomes insignificant. After controlling for subjective indicators, being semi-skilled does not influence subjective social status, but only if one holds high-skilled occupations. This confirms that being semi-skilled instead of low-skilled is not enough to convince people to place themselves higher in society and maybe demonstrates the struggling nature of the middle class in South Africa (Bhorat et al., 2019).

Finally, model 3 includes different race and income groups as a determinant of subjective social status. Race is expected to be an essential indicator of subjective social status in South Africa, in line with the history of colonialism and apartheid that has influenced the perceived social status in which individuals from different race groups see themselves (Seekings, 2007). With Africans as the reference group, the results are positive and significant for Coloured, Indian, and White population groups, which means that Africans tend to see themselves on a lower step of society than other race groups (consistent with other South African-focused studies, Seekings, 2007 and Posel & Casale, 2011).

For the income group, results show that the middle 40% and top 30% would see themselves as higher than the bottom 30%. Therefore, belonging to different income groups does matter when determining subjective social status, consistent with the literature (Lindemann & Saar, 2014; Singh-Manoux et al., 2003). While both race and income classifications seem to drive subjective social status, their significance could be due to the high racial and income divisions in South Africa that have been debated as fundamental driving forces behind the psyche of how people make choices about their class status (Roberts, 2014). This could influence the relationship between objective factors and subjective social status and creates a need to assess the relevance of objective factors in the subjective social status model for different social groups.

Table 8, in the appendix, reports on the interaction effects to assess how different race and income groups could influence the relationship between subjective social status and objective factors, precisely occupation and education. While many of the interaction effects were found to be insignificant, some showed significance.Footnote 6 This indicates that classification by race and income group plays a significant role in the relationship between objective and subjective social status and provides a motivation that these varying factors behind subjective social status need further exploration. Tables 4 and 5 show subjective social-status determinants for different race and income groups.

Table 4 shows the results for the ordered probit model by race. The table shows that semi-skilled occupations influence subjective social status only for Indians, which means that for Africans, Coloureds, and Whites, being semi-skilled does not influence subjective social status. Due to the lingering legacy of apartheid, Africans and Coloureds generally see themselves at the bottom of the social ladder and might need more than a semi-skilled job to make them feel they can choose a higher social position. We can see this with the highly skilled variable being significant for Africans and Coloureds, while for Whites, occupational status is not a significant predictor of subjective social status.

Education plays a positive and significant role for all race groups. The higher an individual’s education, the higher their perceived social status, regardless of race, and consistent with the literature (Chen & Williams, 2018; Evans & Kelley, 2004; Singh-Manoux et al., 2003). Subjective social mobility is significant only for Indians. At the same time, class imagery is also significant and negative, but only for Africans and Coloureds, meaning that individuals in these previously disadvantaged population groups value how they view society when choosing their subjective social status. This is not surprising since Africans and Coloureds make up the largest share of those living in poverty and aligns the important role inequality perceptions play for those from low-income groups (Oddsson, 2018).

Interestingly, class imagery does not matter for Whites and Indians, who tend to see themselves on higher steps in society (refer to Fig. 2), indicating that individuals who see themselves on a higher step do not consider the structure of society but assign more conceptual weight to other factors. Lastly, the control variables age and gender were also assessed, with both gender and age being insignificant across all race groups, confirming the relative insignificance of these personal characteristics driving perceived social status.

This study also aims to decompile the determinants of subjective social status by different income groups. The results in Table 5 show that the importance of objective factors in determining subjective social status differs by income group. For instance, the middle-income group is the only group were occupation status shapes subjective social status. Occupation status does not shape subjective social status for individuals in lower and top income positions, which might explain why these individuals in the bottom and top income groups still consider themselves in the middle of society. Likewise, with different race groups, education is highly significant for all the income groups, except for the top income group, and confirms the importance of education in explaining individuals’ subjective social status. Also, the insignificance of occupation and education for the top income groups highlights the multidimensionality of how subjective social status is determined. It could be that those at the top of the income distribution are much more attentive to their income and place less focus on other objective and subjective factors when determining their social status. Furthermore, observing class imagery is only significant for the lower-income group. This further points to varying factors that influence the subjective social status of people in different population and income groups.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study aimed to assess the dynamics behind people’s perceived social status. While South Africa suffers from extreme levels of inequality, mainly led by the increasing income polarization and a struggling middle class, social perceptions about status still strongly point to a middling tendency. A dynamic that drives the variation between individuals’ social placement and their actual economic status. International studies like Evans and Kelley (2004), Hout (2008) and Lindemann and Saar (2014) show that objective factors determining subjective social status are vital but also confirms that perceived social status is a multidimensional concept reaffirmed by individuals’ middling tendencies when choosing their social position. While the dynamics behind individuals’ subjective social status have been assessed for various developed countries, there remains little evidence on what drives people’s perceived social status in a developing African country case. Using the 2009 ISSP Social Inequality survey, the study assesses the dynamics behind subjective social status in South Africa. We hypothesize that different population and income groups would have varying factors influencing their perceived social status in a highly unequal society.

While we found a strong middling tendency among South Africans, the study found that objective factors, education, and occupation status are significant in determining an individual’s subjective social status, similar to findings of other international studies (Evans & Kelley, 2004; Haddon, 2015; Oddsson, 2018). The higher the education and occupation status, the higher people perceive their social status. The results also show that subjective social mobility and class imagery perceptions influence people’s subjective social status, confirming the multidimensionality among subjective social status perceptions. Consistent with findings from Kelley and Kelley (2009), the lower people view their social mobility, the lower they see themselves, and the more unequal people view society’s structure, the lower they see themselves in society. However, it should be noted that the relationship between perceived social mobility and subjective social status is significant but only for those with low perceived mobility. Meaning those who perceive that their social status has decreased see themselves on lower social steps than those who perceive no mobility, while upward-mobility perceptions are insignificant in driving subjective social status.

We also tested the hypothesis that the dynamics behind subjective social status are heterogeneous for different races and income groups. Conducting separate ordered probit models shows that the relationship between perceived social status and objective factors differs by race and income group. For instance, Africans and Coloureds are indifferent to low or semi-skilled occupations and tentatively choose a lower social status. Only when they have a highly skilled job would they choose a higher social status. Education is significant for all race groups, highlighting the importance of education as a driver for individuals to see themselves moving up the social ladder. Subjective social mobility and class imagery are also significant for Africans, Coloureds, and Indians, but not for Whites. This indicates that the lingering legacy of apartheid and the connection between subjective dynamics are more robust for those who were discriminated against in past regimes.

The study also assesses the determinants of individuals’ subjective social status in different income groups. For example, individuals who fall in the middle-income group put more weight on their occupation status than those at the top and bottom of the distribution. However, education remains significant for most income groups and reiterates the importance of education as a predictor of subjective social status. Class imagery is also significant for those at the bottom of the income distribution. None of the variables are significant for those at the top of the distribution and indicates the multidimensionality of how individuals determine their social status.

There are some limitations of this study. Firstly, some variables, like subjective social mobility, are only included in the 2009 ISSP Social Inequality survey, restricting the assessment to a cross-sectional analysis. Moreover, a large share of the sample, largely unemployed, has been removed from the regression analysis. Mainly because of the difficulty identifying their occupation status and the fact that most of the unemployed could not answer the subjective social mobility question due to never having a job. Future studies could be dedicated to increasing sample sizes by including the unemployed through alternative measures of occupation status and subjective social mobility.

Overall, the results provided vital insight into the determinants of subjective social status in South Africa. The results confirm the varying factors behind the determination of subjective social status for different populations and income groups. With the high and persistent racial inequality and increasing income polarization, yet a strong middling tendency, the study provides valuable insights into how individuals from different population and income groups determine their perceived social status in this highly unequal society while also informing the government about people’s mobility, inequality, and stratification perceptions that add supportive information for established objective measures (Kroll & Delhey, 2013). Also, since perceptions about one’s social status tend to influence subjective well-being, mental health, and voting behavior, understanding the dynamics of subjective social status is vital for policymakers and future subjective indicator research in South Africa.

Notes

Household income is measured as an income rank measure in the ISSP dataset that asks the household respondent a question about the households’ relative rank position with the distribution of factual income.

The.

The unequal intervals focus on assigning higher scores to account for the degree of inequality (0, 47, 80, 93 and 100).

In order to estimate the multinomial probit model the dependent variable, the 10- step subjective social status rank measure, was recoded into three grouped categories, a lower group (step 1 to 3), middle group (step 4 to 6), and higher group (step 7 to 10). With the base category for the analysis being the middle group and the choice of three categories motivated by literature (Burger et al., 2015; Sosnaud et al., 2013).

We also assessed the class decomposition of those who have downward mobility perceptions and shows that around 88% of those who perceive lower mobility belongs to the lower and middle income groups.

We also performed an f test on the joint significance of the interaction effects and found the p value to be 0.000. Meaning we can reject the null hypothesis that interaction terms coefficients are equal to zero and confirm that some of the interaction effects should be significant in explaining subjective social status.

References

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Andersen, R., & Curtis, J. (2012). The polarising effect of economic inequality on class identification: evidence from 44 countries. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(1), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2012.01.002

Bhorat, H., Oosthuizen, M., Lilenstein, K., & Thornton, A. (2019). The rise of the “missing middle’ in an emerging economy: The case of South Africa. University of Cape Town.

Burger, R., Steenekamp, C., Van der Berg, S., & Zoch, A. (2015). The emergent middle-class in contemporary South Africa: Examining and comparing rival approaches. Development Southern Africa, 31(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2014.975336

Castillo, J. C. (2011). Legitimacy of inequality in a highly unequal context: Evidence from the Chilean case. Social Justice Research, 24(2011), 314–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-011-0144-5

Chen, Y., & Fan, X. (2015). Discordance between subjective and objective social status in contemporary China. Journal of Chinese Sociology, 2(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-015-0017-7

Chen, Y., & Williams, M. (2018). Subjective social status in transitioning China: Trends and determinants. Social Science Quarterly, 99(1), 406–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12401

Engelhardt, C., & Wagener, A. (2014). Biased perceptions of income inequality and redistribution (June 12, 2014). CESifo Working Paper Series No. 4838. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2463129

Evans, M. D. R., Kelley, J., & Kolosi, T. (1992). Images of class: Public perceptions in

Evans, M. D. R., & Kelley, J. (2004). Subjective social location: Data from 21 nations. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 16(1), 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/16.1.3

Evans, M. D. R., Kelley, J., & Sikora. J. (2013). Images of class and its effects on subjective social location: Public perceptions around the world and their consequences. Paper presented at the American Sociological Association Meeting, August 10, New York.

Francis, D., & Webster, E. (2019). Poverty and inequality in South Africa: Critical reflections. Development Southern Africa, 36(6), 788–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2019.1666703

Goldman, N., Cornman, J. C., & Chang, KegreenM. (2006). Measuring subjective Social Status: A case study of older Taiwanese. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 21(2006), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-006-9020-4

Greene, W. H. (1991). Econometric analysis. Macmillan.

Gugushvili, A. (2020). Social origins of support for democracy: A study of intergenerational mobility. International Review of Sociology, 30(2), 376–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2020.1776918

Haddon, E. (2015). Class identification in New Zealand: An analysis of the relationship between class status and subjective social location. Journal of Sociology, 51(3), 737–754. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783314530529

Hout, M. (2008). How class works: Objective and subjective aspects of class since the 1970s. In A. Lareau & D. Conley (Eds.), Social class: How does it work? (pp. 25–64). Russell Sage Foundation.

ISSP Research Group. (2017). International social survey programme: Social inequality IV—ISSP 2009. ZA5400 Data file Version 4.0.0. [GESIS Data Archive]. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12777

Kelley, S. M. C., & Kelley, C. G. E. (2009). Subjective social mobility: Data from 30 nations. In M. Haller, R. Jowell, & T. Smith (Eds.), Forthcoming as chapter 6 in charting the globe: The international social survey programme (pp. 1984–2009). Routledge.

Kim, J. H., & Lee, C. S. (2021). Social capital and subjective social status: Heterogeneity within East Asia. Social Indicators Research, 154(2021), 789–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02548-9

Kirsten, F., Botha, I., Biyase, M., & Pretorius, M. (2022). The impact of subjective social status, inequality perceptions, and inequality tolerance on demand for redistribution. The Case of a Highly Unequal Society, Studies in Economics and Econometrics, 46(2), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03796205.2022.2126998

Knell, M, & Stix, H. (2017). Perceptions of inequality. Oesterreichische Nationalbank Working Paper series no 216.

Kroll, C., & Delhey, J. A. (2013). Happy nation? Opportunities and challenges of using subjective indicators in policymaking. Social Indicators Research, 114, 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0380-1

Kuhn, A. (2019). The subversive nature of inequality: Subjective inequality perceptions and attitudes to social inequality. European Journal of Political Economy, 59(C), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2019.04.004

Leibbrandt, M., Woolard, I., Finn, A., & Argent, J. (2010). Trends in South African income distribution and poverty since the fall of apartheid. Oecd Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers 101. OECD.

Leibbrandt, M., Finn, A., & Woolard, I. (2012). Describing and decomposing post-apartheid income inequality in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 29(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2012.645639

Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2006). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata (2nd ed.). Stata Press.

Lindemann, K. (2007). The impact of objective characteristics on subjective social status. Trames, 11(61/56), 54–68.

Lindemann, K., & Saar, E. (2014). Contextual effects on subjective social status: Evidence from European Countries. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 55(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715214527101

Mahmood, T., Yu, X., & Klasen, S. (2019). Do the poor really feel poor? Comparing objective poverty with subjective poverty in Pakistan. Social Indicators Research, 142(2019), 543–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1921-4

Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structure. Free Press.

Oddsson, G. (2018). Class imagery and subjective social location during Iceland’s economic crisis, 2008–2010. Sociological Focus, 51(1), 14–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2017.1341251

Ostrove, J. M., Adler, N. E., Kuppermann, M., & Washington, A. E. (2000). Objective and subjective assessments of socioeconomic status and their relationship to self-rated health in an ethnically diverse sample of pregnant women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 613–618. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.613

Posel, D. R., & Casale, D. M. (2011). Relative standing and subjective well-being in South Africa: The role of perceptions, expectations and income mobility. Social Indicators Research, 104(2011), 195–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9740-2

Roberts, B. J. (2014). Your place or mine? Beliefs about inequality and redress preferences in South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 118(2014), 1167–1190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0458-9

Schotte, S., Zizzamia, R., & Leibbrandt, M. (2018). A poverty dynamics approach to social stratification: The South African case. World Development, 110(C), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.024

Seekings, J., & Nattrass, N. (2008). Class, race, and inequality in South Africa. Yale University Press.

Seekings, J. (2007). Perceptions of class and income in post‐apartheid Cape Town. Centre for Social Science Research Working Paper No. 198, Cape Town.

Shaked, D., Williams, M., Evans, M. K., & Zonderman, A. B. (2016). Indicators of subjective social status: Differential associations across race and sex. SSM—Population Health, 2(2016), 700–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.09.009

Singh-Manoux, A., Adler, N. E., & Marmot, M. G. (2003). Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 1321–1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00131-4

Sosnaud, B., Brady, D., & Frenk, S. M. (2013). Class in name only: Subjective class identity, objective class status, and vote choice in American Presidential Elections. Social Problems, 60(1), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1525/SP.2013.60.1.81

Sudo, N. (2019). Why do the Japanese still see themselves as middle class? The impact of socio-structural changes on status identification. Social Science Japan Journal, 22(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jyy047

Visagie, J., & Posel, D. (2013). A reconsideration of what and who is middle class in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 30(2), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2013.797224

Williams, R. A., & Quiroz, C. (2019). Ordinal regression models. In P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, & R. A. Williams (Eds.), SAGE research methods foundations. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036885901

Wolf, R., & Gould, W. (1998). An approximate likelihood-ratio test for ordinal response models. Stata Technical Bulletin, StataCorp LP, 7(42). https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:tsj:stbull:y:1998:v:7:i:42:sg76

Yamaguchi, K., & Wang, Y. (2002). Class identification of married men and women in America. American Journal of Sociology, 108(2), 440–475. https://doi.org/10.1086/344813

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Johannesburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Appendix Tables

6,

7 and

8.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kirsten, F., Botha, I., Biyase, M. et al. Determinants of Subjective Social Status in South Africa. Soc Indic Res 168, 1–24 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03122-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03122-9

Keywords

- Social and economic stratification

- Equity, justice, inequality, and other normative criteria and measurement

- Sociology of economics