Abstract

Against the background of continuing gains in female education and labour market participation and rising migration, we investigate whether women work in occupations which match their educational qualifications and whether migrant women face double penalty in being overqualified for their jobs. Using the data from the European Social Survey covering 2002–2020 with detailed information about occupation and educational attainment, we show that migrant women are significantly more likely to be overqualified in their jobs relative to native women. We explore the role of individual, institutional and workplace factors, as well as attitudes, to explain the overeducation of foreign-born women compared to native-born women. While parental education, workplace and destination country characteristics are all important factors in women’s overqualification, they do not explain the immigrant women’s disadvantage. The overqualification of migrant women is particularly notable amongst low and medium skill groups and in middle income households. These results inform the policy efforts to mitigate the skills waste of migrant women by documenting the gaps, identifying the target groups and suggesting potential channels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Skills waste for migrants has been long documented. Overwhelmingly men have been at the focus of this literature. In this paper, we shift the focus to the other half of the migration story, to immigrant women, who are at an intersection of migrant and gender disadvantage in the labour market. Female migrants comprise slightly more than half of all international migrants in Europe and Northern America (Migration data portal, 2022). However, the evidence on the extent of skill waste and the drivers of skill waste for immigrant women is lacking. This paper addresses the gap in evidence on skills waste in context of gender and immigrant status. We focus on overqualification as our measure of mismatch to capture the skills waste, a situation in which the skills of individuals, who are capable of handling more complex tasks, are underused or wasted (OECD, 2011). In this paper we provide evidence for skills waste through occupation-education mismatch for migrant women across skill groups. We employ a large-scale panel data with more than 121,000 observations across 31 European countries with large immigrant inflows or stocks during the period studied (2002–2020). Importantly, we analyse the drivers of skills waste to guide the policies to mitigate this problem.

In recent times, countries have made big gains in improving access to education and importantly, in reducing the gender gap in access to education. In fact, recent trends have benefitted women more. In 2019, 55% of new entrants into tertiary education were women and if current trends continue, more women than men will graduate with a tertiary degree before they turn 30 (OECD, 2021). This increased education participation is translating into narrowing of gender gap in the labour market; however, women still have lower labour force participation than men and are more likely to work part-time. While the issue of female labour force participation has been widely explored, there has been relatively less attention on the nature of employment of female workers once they participate in the labour force. We address this gap by exploring the extent to which women utilise their educational qualifications in the labour market in Europe, the drivers of the under-utilisation of women’s qualifications and the extent to which they explain the immigrant-native gap.

While the occupation-qualification mismatch has been extensively documented in the literature, the focus has mainly been on men. As noted by Addison et al. (2020) women are distinguished by their absence in these studies. Given the gains in education discussed above, it is even more pertinent to investigate the skills waste in form of underutilisation of qualifications in jobs for women. Addison et al. (2020) show that college-educated females are significantly more mismatched than males in the US. Similarly, waste of skills and qualifications due to job mismatch, the imperfect international transferability of human capital (Aleksynska & Tritah, 2013; Chiswick & Miller, 2009; Tani, 2012), has been consistently shown for migrants (see Piracha & Vadean, 2013 for review). Again, the focus has been on migrant men and we contribute to the literature and policy discussion by providing the evidence for migrant women. Using the data from 31 countries in Europe between 2002 and 2020, we investigate if the migrant women face a significant double penalty (through gender and migrant status) in the labour market. We pay particular attention to the intersectionality, our analysis is informed by immigrant and gender contexts.

We provide cross-country evidence for the extent of over-qualification for immigrant women, extending the studies on immigrant women’s labour participation and employment which have so far focused on single country such as the US (Blau et al. 2013; Fernández and Fogli, 2009; Fortin, 2005). We exploit the panel structure of the data to distinguish between individual, institutional and workplace drivers of women’s overqualification. This, our third contribution, provides guidance for policies that can mitigate the challenge of overqualification for migrant women. Utilisation of women’s skills is expected to increase in an environment that is supportive of women. On the personal front, intergenerational transmission suggests that higher levels of parents’ education will increase the level of qualifications for women (Muzumdar et al., 2019) and reduce gender gaps in children’s education (Dong et al., 2020). It is unclear whether it would lead to better jobs for women and whether it explains the disadvantage for migrant women.

Women are likely to be better matched to their jobs if the institutional structures surrounding the labour markets are supportive of gender equality. We harness the panel structure of the employed data to explore these potential policy relevant levers. Using the variations in women’s educational and unemployment levels and attitudes towards gender equality across countries and over time; we demonstrate their important role in occupation-qualification match. We propose that gender attitudes not only drive the extent of female labour market participation in terms of hours but also influence the choice of occupations and the nature of her employment. For example, females may choose not enter (or remain) in highly skilled occupations, even if they have suitable qualifications, if they have to meet the particular societal expectations about home or family responsibilities. Fortin (2005) explores the effect of gender role attitudes on female employment and part time status in OECD countries. Using the world values survey, the study finds that traditional gender values and work values (such as views about competition) have significant explanatory power in explaining women’s employment status. We use the responses to questions “women should be prepared to cut down on paid work for sake of family” and “men should have more right to job than women when jobs are scarce” to explore the role of gender attitudes in occupation mismatch of migrant women. We note that these factors are relevant to all women (native and migrant), given the focus of the paper on migrant women (relative the native women) they are important context for policy makers. In addition to the above factors, we also explore the role of migrant specific attitude variables.

The other set of variables relate to the structure of jobs. On one hand, institutions such as trade unions and public sector employment could reduce gender inequality by reducing discriminatory practices and policies. On the other hand, Aleksynska and Tritah (2013) find that trade union membership increases the relative risk of overeducation of immigrants, possibly through higher labour market rigidity and higher separation costs. For policy conclusions it is important to know the effect of these institutional settings on underutilisation of immigrant women’s qualifications. We also document the extent of immigrant women’s overqualification across skills groups and household income groups to enable policy-makers to target their efforts.

Understanding the extent of overeducation has implications for debate on gender wage convergence (Blau & Kahn, 2006). If women are in occupations which do not fully utilise their education and skills, returns to additional education will be low and the efforts to close the gender wage gap need to focus on better utilisation of women’s education through appropriate matching in the labour market. Our results show that immigrant women are more likely to be overqualified in the low and medium skill groups. Thus, focusing on these heterogeneities across occupations is important.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the main data source; Sect. 3 explains the empirical strategy and Sect. 4 provides descriptive statistics. Section 5 presents the estimation results; and Sect. 6 provides a discussion of results in terms of policy implications and concluding remarks.

2 Data

To conduct the econometric analysis of occupation-education mismatch of immigrant women within a cross-country framework, we use the most recent data from the European Social Survey (ESS). ESS is a biennial—partly repetitive—cross-section survey conducted in more than 30 countries, including members of the European Union and beyond (e.g. Norway, Switzerland, Turkey or Ukraine). The survey covers all persons aged 15 years old or older who are residents within private households regardless of nationality, citizenship or legal status in the participating countries mainly located in Europe. In addition to the conventional demographic and socioeconomic variables of individuals, the survey provides details about various labour market indicators such as un/employment, labour force participation, detailed occupational groups or total household income (in deciles). It also measures attitudes, beliefs and behavior patterns on various social issues ranging from gender roles, politics or climate change.

We use the individual data from nine waves covering the period 2002–2020 and focus only on women of working age (aged 20–65) who are employed at the time of the survey.Footnote 1 As most of the literature on labour market integration focuses mainly on men without a good reason, we choose to focus on women that represent about half—and even slightly more than half depending on the country—of the populations in the sample. Notwithstanding the general challenges of women integrating into the labour markets, this paper highlights the double challenges that women face as immigrants in the job market and the extent to which these challenges lead to skill wastes in the occupations. We define immigrant as an individual who is born in another country than the country of residence. Focusing only on employed women gives us a sample of more than 121,000 observations composed of native- and foreign-born individuals from diverse origins (more than 150 countries of origin), where the latter group makes up about 9% of the overall sample of women. This sample covers 31 destination countries as listed in the following table. We note that not all countries have participated at each round of the survey, but a large number of them participated in nearly all waves. The survey data comes with sample and design weights that allow conducting cross-country comparable research with a representative data; therefore, all descriptive statistics and estimations in the following use the sample and design weights (Table 1).

The countries in the sample have received large flows of migrants during the past few decades from within and outside of Europe (Brücker et al., 2013), following diverse economic, political and historical developments as well as individual aspirations of migrants (Akgüç & Beblavý, 2019). We use a pooled sample putting together all waves of the survey in order to have a sufficiently large sample that would still allow to take into account variation in various control variables as well as in the outcome variable (i.e., the probability of overqualification in occupation held). The proxy measure for the outcome variable, is explained in the next section.

3 Empirical Strategy

The first step in our empirical analysis is to identify and measure the occupation-education mismatch. We follow the well-established realized matches’ procedure (see Chiswick & Miller, 2010a, 2010b and Aleksynska & Tritah, 2013 for applications of this approach) of comparing the individual’s education level to the mean educational levels within each occupation in a given country. First, the variable ORUi is constructed as follows:

This variable construction is improved (and extended) from the previous papers’ approaches in two ways. First, it takes into account a corrected measure of years of education by calculating the average years of educational attainment by level for each country, which shows variation for the length of each level of education. Second, the constructed mismatch variable takes into account 4-digit occupation codes (in contrast to 1-digit occupation codes as done by others), which allows to measure more precisely the outcome variable and thus captures better the different occupations’ mean years of education as well as its standard deviations within a country. Last but not least, the constructed variable is up-to-date with the most recent waves of the data, reflecting the recent developments in the educational attainment trends as well as occupational changes across countries. We include both men and women in the calculation of ORU, since both genders can (and do) work in the same occupations and hence are the appropriate reference for the average qualification in the occupation.

Table 2 displays a brief overview of the constructed mismatch variable by nativity status (i.e., native- vs. foreign-born women). We observe that slightly more than three quarters of native-born women are correctly matched in their occupations, in the sense that their educational attainment is within one standard deviation range of the average educational attainment in an occupation in a given country. In contrast to that, only two thirds of immigrant women hold occupations that match their educational attainment. Moreover, as anticipated, immigrant women are more likely to be both under—(to a much less extent though) and over-qualified in their occupations compared to the native women, with the latter discrepancy being more substantial (14.3% for native- vs. 23.1% for foreign-born).Footnote 2 One of the main goals of this paper is to identify and understand the sources of this mismatch, however, given that the type of mismatch on the upper end, i.e., overqualification or skill waste, appears to be the most substantial than the underqualification, for the rest of the analysis, we only focus on the overqualification (or skill waste). Moreover, comparing the outcomes for native and immigrant women will help us to understand the role of cultural backgrounds in the observed gaps. For comparison, 15% of native men and 21.3% of migrant men are overqualified. Not only there is a substantial higher probability of overqualification for migrant women, the gap between immigrant and native-born women has worsened over the time (see Appendix Fig. 1).

The empirical approach is to estimate the probability of the incidence of overqualification (i.e., being one standard deviation above the mean educational attainment in an occupation in a given country) using a probabilistic model (probit). Specifically, each binary dependent (outcome) variable (whether a woman is overqualified or not in her occupation, given her educational attainment) \({{\varvec{Y}}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{c}}{\varvec{t}}}\) of individual i in country c at time t is estimated by probit using the following baseline model:

where X includes individual specific characteristics such as age (and squared), educational attainment in levels, civil status including four states (single, married, divorced, widow), household characteristics such as an indicator of area of residence (urban or rural) or number of children. Given the focus of this analysis on female workers, we are particularly interested in how children affect the occupational outcomes.Footnote 3 We also control for parental education (both educational attainment of mother and father in three levels) to account for possible intergenerational and cultural transmission—which are particularly important in the context of immigrant labour market outcomes (e.g. Akgüç & Ferrer, 2015)—effects in the occupational outcomes of women.

Last but not least, we investigate whether workplace characteristics play a role in explaining the risks of overqualification in the job. For this category of controls, we include an indicator for trade union membership, type of organization worked for (public or private), contract duration (permanent or temporary) as well as an indicator for company size (small, medium or large).

Finally, the matrix X also includes destination country fixed effects (\({{\varvec{\eta}}}_{{\varvec{c}}}\)), year effects (\({{\varvec{\mu}}}_{{\varvec{t}}}\)) and a random error term (\({{\varvec{\varepsilon}}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{c}}{\varvec{t}}}\)). All our regressions use pooled cross-sections of the ESS data (individuals across countries over time). We, thus, estimate the probability of overeducation for individuals, controlling for country and year fixed effects.

As the ESS covers many countries comprised of various labour market institutions and integration patterns for immigrants, the distribution of the occupation-education mismatch, in particular the overqualification, of immigrant women displays large variations across destination countries. The proposed empirical strategy exploits this variation to identify the effects of culture and institutions on the incidence of occupational overqualification.

Similar to the strategy by Bredtmann and Otten (2013), we always control the effects of (time-invariant) destination country characteristics on the occupation-education mismatch of women by including country fixed effects in Eq. 1. These fixed effects would capture the time-invariant cultural, institutional and economic context in which women make their occupational decisions and end up in the jobs they hold.

While the size and significance of the country fixed effect provide initial insights into the role of culture and institutions, they do not offer insights into host country institutions that drive the brain waste. We explore the drivers of these host country differences by explicitly controlling for country characteristics, replacing fixed effects by these variables. We focus on two sets of host country variables. The first set of variables consists of female employment rate and average female educational attainment (years of education), and they relate to women’s role in the labour market. The probability of overeducation of migrant women is expected to decrease with feminization (either by having more women employed in the labour market or by having women with more educational attainment in general) of the labour force in the host country labour market. Through these destination country variables, we estimate and test whether, for example, a generally high employment (or high educational attainment) of women in the destination labour market plays an offsetting role in decreasing the chances of skills waste for immigrant women.

The second set of variables refer to the attitudes towards women’s work in the host country. Since the survey includes two relevant questions pertaining to the gender roles in the labour market, we also estimate the effects of these two attitudes variables—namely, one on whether men should have more right to a job than women, and another one on whether women should be prepared to cutdown on work to take on more family responsibilities—on the probability of overqualification of women. The answers to questions “men should have more right to job than women when jobs are scarce” and “women should be prepared to cut down on paid work for sake of family” are coded in an increasing scale corresponding to a range from “agree”, “indifferent” to “disagree.”

Given the focus on migrant women we also include the attitudes towards immigrants in the host country. The two relevant attitude variables in the survey are: (1) immigration is bad or good for the host country’s economy, (2) immigrants make the country worse or better place to live. Both of these variables are measured as a scale from 0 (bad for (1) or worse for (2)) to 10 (good for (1) and better for (2)).

As discussed above, to control for the origin country and possible linkages with the cultural background, we use the parental educational attainment to capture the cultural transmission mechanism. The idea is to capture whether coming from a highly educated parental background leads women to make better occupational choices to decrease the skills waste.

In terms of estimation strategy, we use a multivariate probit regression framework to estimate the binary outcome variable (overqualification). As the raw probit coefficient estimates are hard to interpret, we calculate and report the average marginal effect. The empirical results are mainly organised in a way that a batch of thematic control variables are introduced gradually to investigate their impact on the key coefficient of interest, immigrant status indicator, which describes the gap between native and immigrant women in occupational overqualification (or skills waste).

Finally, we estimate robust standard errors that are clustered at the country level. All empirical analysis is done using appropriate weights as provided by the data.

4 Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 provides summary statistics of the individuals in the sample distinguishing them by native-immigrant status, as defined earlier. Accordingly, native women are about 2 years older than immigrant women, on average. In terms of educational attainment, immigrant women are overrepresented both at the lowest (primary or less) and highest (tertiary) levels, with the difference being the most significant for the higher end of the educational distribution. The civil status shows more or less similar trends for both groups of women. In terms of household characteristics, immigrant women have a slightly higher fertility rate than native women (0.9 vs. 0.8 kids on average, respectively), and are significantly more likely to live in urban areas (42 vs. 28%, respectively).

When we look at the parental educational background, we see a similar pattern as observed for the individuals in the sample: fathers and mothers of immigrant women are overrepresented both at the lowest and highest educational levels compared to the parents of native-born women, again the difference being more substantial at the higher end of the educational attainment. In other words, the share of highly educated parents of immigrants is higher than that of natives.

Looking at the workplace characteristics, we observe that immigrant women are less likely to be trade unions members (23 vs. 31%, respectively) and to have a permanent contract (68 vs. 75%, respectively) than native women. They are also less likely than native women to work in public or state-owned organizations.

While the focus of this analysis is on overqualification (the intensive margin), the labor force participation (the extensive margin) is an important context for the analysis. Immigrant women in Europe have lower labor force participation than native women on average, though there are differences across countries. While this pattern is consistently observed for Northern/Western Europe, overall female labor participation is low in the Southern or Eastern Europe (Schieckoff & Sprengholz, 2021). In the US, 58% of migrant women participated in labor force in 2000 compared to 76% of native women (Blau et al., 2011). Data employed in this paper shows that 68.1% of native women and 65.6% of migrant women participate in the labor force, however, as illustrated in Fig. 5, there are large variations across countries. Labor force participation by marital status, family income, and labor market attitudes (reported in Figs. 2,3, 4), show that women’s labor force participation is positively associated with being single, higher income household and more gender equal attitude about women’s labour force participation.

5 Results

The results of the estimations from Eq. (1) are reported in Table 4. The table reports average marginal probabilities. Reflecting the statistics reported in Table 1, immigrant women have 9% points higher probability of being overqualified. Adding country and year fixed effects brings down the coefficient of the immigrant variable by 0.6% points (from column 2 to 3), but the native-immigrant gap in overqualification remains significant. Controlling for woman's own background characteristics (column 3) shows that as expected, this probability increases with education. Compared to women with primary or less educational attainment, the probability of overqualification is 27% points higher for women with post-secondary education and 36% points higher for women with tertiary education. Being married, perhaps due familial commitments, and living in big cities (which might be associated with better labour market integration of women possibly due to availability of a wider range of occupations options with different educational requirements in larger agglomerations) slightly lowers the probability of overqualification, but it does not explain the disadvantage of immigrant women. Similar pattern is observed when we control for parents' education (in column 5). Although, both mother’s and father’s higher education reduce the probability of overqualification (and mother’s education has higher effect compared to father’s education), even after adding these rich set of controls, immigrant women have a significant higher probability of being in jobs that do not fully utilise their qualifications and result in skills waste. Note that the probability of overqualification reduces with years since migration, however, the effect is small.

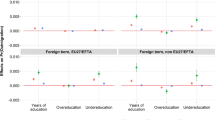

Table 5 reports the role of destination country characteristics relevant for women’s education-occupation mismatch. First, we replace destination country fixed effects with female employment rate and mean years of female education in the destination country in column 1. An increase in female employment rate reduces the probability of women’s overqualification by 19% points while an increase in mean years of female education has a statistically significant but a smaller 2% points decrease. In column 2, we explore the effect of attitudes towards women in labour force. The variable capturing women’s right to job relative to men’s is not found to be statistically significant. In contrast, the decrease in proportion of people who think that women should cut down on work for family reduces the probability of overqualification by 9% points. Again, in both these specifications, our main variable of interest remains significant, migrant women are 10% points more likely to be overqualified. In column 3, we investigate the role of general attitudes towards immigrants in the probability of overqualification of women. Results suggest that although the attitude variable on whether immigrants have a good/bad impact on host economy is not significantly estimated, the second attitude variable indicating that immigrants make the country a better place to live (the higher is the value, the better they make the host a better place to live) has a negative impact, with a nearly 4% points decrease, on the overqualification of immigrants. In other words, in countries with a positive attitude towards migrants, the immigrant women are less likely to be overqualified.

So far, we have investigated the role of woman’s characteristics, parental education, and host country characteristics in the education-occupation mismatch. To help inform policy measures to address the issue of overqualification, we document the prevalence of women’s overqualification across workplaces and occupations groups by turning our attention to the employment side of the story. Results in Table 6 show that these are important aspects. Trade union membership reduces probability of overqualification by 2% points and being on a permanent contract reduces it by 4% points. Women working in a public sector are also better matched to their occupations in terms of their qualifications compared to women employed in private sector. The size of the company does not have a statistically significant effect. While accounting for these workplace attributes reduces the probability of overqualification of migrant women compared to earlier results, immigrant women are still 7% points more likely to be overqualified.

Results in column 2 suggest that the occupation distribution could be an important mediator for migrant women in explaining the incidence of overqualification. Relative to legislators, senior officials, managers (the reference occupational group), professional women have lower probability while women in all other occupations have higher probability of overqualification. Interestingly, there are no significant differences between immigrant and native women once we account for the occupations.

We further explore these differences by occupational skill groups in Table 7. Occupations are divided into low, medium and high skills groups as per ILO ISCO classification of occupations.Footnote 4 According to this classification, low occupation-skill group includes elementary occupations; medium occupation-skill group includes clerks, service, shop and market sale workers, skilled agriculture and fishery workers, craft and related trade workers, plant and machine operators and assemblers; and high occupation-skill group includes legislators, senior officials, managers, professionals, technicians and associate professionals. We run the probit models as described earlier and report the average marginal effects for each of these occupation-skill groups to see whether different patterns are observed across these groups. Results reported in Table 7 show significant heterogeneity across occupation groups. Migrant women have 2% point higher probability of being overqualified in low and medium skill occupations. In these occupations, trade union membership plays important role in reducing occupation qualification mismatch. Public sector and size of the company have a significant effect in medium and high skilled occupations.

The results for high skill occupations show that migrant women as less likely to be overqualified in this group, in contrast to immigrant women working in low- or medium-skill occupations who are statistically significantly more likely to be overqualified in their jobs than native-born women. This contrasting pattern is also evident for Professionals in Table 6. There are few possible explanations for this result. Firstly, the average level of qualification in these occupations are high, reducing the probability of overqualification. Secondly, given the lower labor force participation of migrant women, these women who are highly skilled are likely to be positively selected. Lastly, it is possible that in amongst highly skilled professionals, the gender gap (not the focus of this paper) is more salient than the gap between migrant women and native women.

Additionally, we explore heterogeneities by household income groups as well. For these estimations, we generate three groups by using the total household income variable available in the data. The lowest (highest) income group corresponds to the lowest (highest) 10th decile of the income distribution, while the middle group represents the income distribution between the 20th and 80th deciles. We run the same probit models and estimate the average marginal effects in each of these income groups to see whether overqualification of immigrant women persists across the income distribution. Results reported in Table 8 show that overqualification of migrant women is mainly observed in the middle-income households, but not at the lower end of the income distribution.

We further explore whether selection into labor force affects the extent of overqualification observed in the results. We extended the models by using a Heckman 2-step specification, where we model the probability of overqualification after accounting for labor market participation decision at the first step, which we explain using instruments such as partner’s labor market status and the two cultural variables about gender and work. The results are reported in the Appendix Tables 9 and 10. There is evidence of interdependence between labor force participation and overqualification and migrant women are less likely to participate in the labor force. Migrant women are significantly more likely to be overqualified than native women and this main finding is consistent even after accounting for selection into labor force.

6 Discussion and Concluding Remarks

In times of declining birth rates and low population growth in most advanced economics, full utilisation of the person’s capacities is not only important for the person themselves, but underutilisation of labour force is also a macroeconomic challenge. In the meantime, European economies are increasingly reliant on migrant labour force, but a successful labour market integration and full utilisation of the latter groups’ skills is less than perfect. In this paper, we show the extent of skill waste in these countries, with a particular focus on migrant women who are significantly over-qualified in their jobs compared to native women.

This occupation-qualification mismatch is mainly observed for women with post-secondary education levels in low and medium skilled jobs in workers from middle-income households and migrant background. Identifying these groups of workers is the first step towards tackling the issue of brain waste. Parents’ educational background plays a significant role in decreasing the likelihood woman’s probability of over qualification, possibility due to increasing acceptance and/or integration of women in the labour market over generations. Parental educational background could even possibly translate into better labour market orientation or guidance of individuals by their educated parents, which might likely reduce brain waste. This suggests that over-qualification might lessen over generations as overall education levels increase. However, the problem of over-education is not solely driven by labour supply considerations of the women themselves. Institutional settings in the countries are an important part of ensuring right matching in the labour market.

We find that women’s position in the labour force and attitudes towards women’s participation in the labour force are important drivers. Higher average levels of education and employment of women in labour force reduces the probability of overqualification. Similarly, more supportive attitudes for women’s work have a significant effect in reducing overqualification. Again, this suggests that overall increasing participation of women and changing attitudes over generations will lessen the mismatch problem over time. However, this should not be assumed and policy efforts to foster greater gender quality, both in terms of labour market and societal attitudes will enable better use of women’s skills.

The third set of important drivers are the institutional features of the workplace. Formal structures such as trade union membership, public sector jobs and permanent contracts reduce the probability of overeducation for women. Interestingly, probability of overqualification is lower in medium size companies. The state, both directly through public sector employment and through the setup of workplace relations, plays an important guide role in reducing women’s occupation-education mismatch. This role of the state is particularly important given the occupational distribution of this mismatch. Overqualification of women is highest amongst elementary occupations and for women from middle household income groups. Policies ensuring better match of women’s qualifications to their jobs, thus, will also reduce overall inequality in the labour market. Our investigation of overqualification of women in Europe offers a way forward to addressing this important social and economic issue.

While it can be expected that the skill waste imposes economic costs on the society, estimating the costs of skill waste is a challenge as the wages are determined by the interaction of demand and supply and there will general equilibrium effects of change in matching in the labour market. We are also limited by data; the ESS survey does not have information on individual wages. However, literature provides a guide to costs of migrant skill mismatch. A report by Migration Policy Institute estimates that skills waste of migrants (men and women) in the USA results in more than $39 billion in forgone wages annually and $10 billion in resulting lost tax payments (Batalova et al., 2016). Adalet McGowan and Andrews (2015) estimate that reducing skill mismatch in OECD countries such as Italy and Spain to the best practice level would lead to 10% increase in allocative efficiency. The costs of skill waste of migrant women are important for the individuals, as well as for the society.

Data shows that the gap between over-qualification of immigrant women compared to native women has worsened over time. An important extension of the present analysis in future work would be to explore the changes over time and to understand the factors driving these changes to inform policy makers.

Notes

At the time of writing this paper, a limited 10th wave has been released including only a few countries. The full 10th wave release is expected during 2023.

We test the distributions reported in Table 2. t-tests—allowing for unequal variances for two groups—for the mismatch variable (as a categorical variable with 1 for under, 2 for matched and 3 for over) as well separate t-tests on each category (under, matched and over) suggests that the null hypothesis that the two groups (native-born and immigrants) are statistically the same is rejected in all tests, except for the t-test for underqualification, where we cannot reject the null. Overall, the two groups are statistically the same as far as underqualification is concerned, but statistically different for the incidences of matched and overqualification at the occupation.

We have also run the models with the variable indicating the age of the youngest child at home and the results remain unchanged.

For more details, see the dedicated ILO webpage: https://ilostat.ilo.org/resources/concepts-and-definitions/classification-occupation/

References

Adalet McGowan, M. and Andrews, D. (2015), Skill Mismatch and Public Policy in OECD Countries, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1210, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5js1pzw9lnwk-en.

Addison, J. T., Chen, L., & Ozturk, O. D. (2020). Occupational skill mismatch: Differences by gender and Cohort. ILR Review, 73(3), 730–767.

Akgüç, M. and Ferrer, A. (2015). Educational attainment and labor market performance: An analysis of immigrants in France. IZA Discussion Paper 8925. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Akgüç, M. and Beblavý, M. (2019). What happens to young people who move to another country to find work? In Youth Labor in Transition (pp. 389–418). Oxford University Press.

Aleksynska, M., & Tritah, A. (2013). Occupation–education mismatch of immigrant workers in Europe: Context and policies. Economics of Education Review, 36(C), 229–244.

Batalova, J., Fix, M., and Bachmeier, J.D. (2016). Untapped talent: The costs of brain waste among highly skilled immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, New American Economy, and World Education Services.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2006). The U.S. gender pay gap in the 1990s: slowing convergence. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 60(1), 45–66.

Blau, F. D., Kahn, L. M., Liu, A., & Papps, K. (2013). The transmission of women’s fertility, human capital, and work orientation across immigrant generations. Journal of Population Economics, 26(2), 405–435.

Blau, F. D., Kahn, L. M., & Papps, K. L. (2011). Gender, source country characteristics, and labor market assimilation among immigrants. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 43–58.

Bredtmann, J. & Otten, S. (2013). The role of source- and host-country characteristics in female immigrant labor supply, MPRA Paper 44544, University Library of Munich, Germany.

Brücker, H., Capuano, S., and Marfouk, A. (2013). Education, Gender and International Migration: Insights from a Panel-Dataset 1980–2010. Mimeo. Nuremberg: IAB Institute for Employment Research.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2009). The international transferability of immigrants’ human capital. Economics of Education Review, 28(2), 162–169.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2010a). Does the choice of reference levels of education matter in the ORU earnings equation? Economics of Education Review, 29(6), 1076–1085.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2010b). The effects of educational-occupational mismatch on immigrant earnings in Australia, with international comparisons. International Migration Review, 44(4), 869–898.

Dong, Y., Bai, Y., Wang, W., Luo, R., Liu, C., & Zhang, L. (2020). Does gender matter for the intergenerational transmission of education? Evidence from rural China. International Journal of Educational Development, 77, 102220.

Fernández, R., & Fogli, A. (2009). Culture: An empirical investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility. American economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(1), 146–177.

Fortin, N. M. (2005). Gender role attitudes and the labour-market outcomes of women across OECD countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21(3), 416–438.

Mazumder, B., Rosales-Rueda, M., & Triyana, M. (2019). Intergenerational human capital spillovers: Indonesia's school construction and its effects on the next generation. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 109, pp. 243–49).

Migration data portal, https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/gender-and-migration, Retrieved on 27 July 2022.

OECD. (2011). OECD Employment Outlook 2011, Chapter 4. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/empl-outlook-2011-en.

OECD. (2021). Education at a glance 2021: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en

Piracha, M. & F. Vadean (2013). Migrant educational mismatch and the labor market. In International handbook on the economics of migration (pp. 176–192). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Schieckoff, B., & Sprengholz, M. (2021). The labor market integration of immigrant women in Europe: Context, theory, and evidence. SN Social Sciences, 1(11), 1–44.

Tani, M. (2012). Does immigration policy affect the education-occupation mismatch? Evidence from Australia. Australian Bulletin of Labour, 38(2), 111–141.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and Tables 9, 10.

Notes: The figure reports the incidence of overqualification of immigrant women compared to native women (the dots are the average gaps across countries at a point in time) and the trend line to illustrate better the evolution of the gap over time

Overqualification of migrant and native women over time.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akgüç, M., Parasnis, J. Occupation–Education Mismatch of Immigrant Women in Europe. Soc Indic Res 170, 75–98 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03066-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03066-0