Abstract

Previous research indicates a positive relation between social trust, institutional trust and subjective well-being. Besides theoretical assumptions and cross-sectional relations, only few studies so far examined the causal structure between these concepts. However, previous studies showed contradictory results, possibly due to different methods and datasets used. Hence, we analyzed the causal structure between the three concepts on the aggregate country-level using the European Social Survey, which offers a total of 217 observations from 30 countries, nested in nine time-points between 2002 and 2018. We targeted a causal effect by using a multilevel bivariate cross-lagged analysis. This way we analyzed if previous values of the respective explanatory variable predicts future values of the respective criterion variable. Using this method, we were able to (1) separate the relevant within-country from the between-countries effect, (2) control for different effects in different countries, (3) control for covariates as well as for autoregression of the respective criterion variable over time, and (4) control for residual correlation between the respective criterion variables. Our results suggest a causal effect from subjective well-being to social trust, but little evidence for a reverse causal pathway. Further, we found no effect from social trust and subjective well-being on institutional trust and only small but negative effects vice versa. The results suggest treating social and institutional trust not as preconditions of subjective well-being, but rather as independent facets for the quality of life of a society as already implemented by the OECD’s better-life index, amongst others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

One important goal for a society is to increase happiness and well-being amongst its residents (Nussbaum, 2001). From an economic standpoint, increasing the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country leads to higher prosperity. Therefore, the GDP per capita was long considered as the most important indicator for the quality of life of a country (Oishi & Schimmack, 2010). However, as shown by Easterlin (1974), economic growth does not correlate with self-reported well-being in the long run. Today, more and more researchers and politicians put a stronger focus on subjective indicators to measure quality of life, mainly assessed via surveys (Diener et al., 2015). This approach focuses on individuals´ assessment of their own life. The most widely used indicator for this purpose is subjective well-being introduced by Diener (2009), which is composed of positive affect, the lack of negative affect, happiness, and life satisfaction (e.g., Diener et al., 2012; see also Glatz & Eder, 2020).

In order to increase subjective well-being, it seems mandatory to understand its causal structure with key predictors. Among others, social and institutional trust belong to these key predictors, although it is still unclear how these two types of trust are associated with subjective well-being. Therefore, in this study we focus on the causal relation of subjective well-being and social and institutional trust, respectively, as well as on the causal relation between the latter two. While previous studies showed positive interrelations between these three constructs (e.g., Calvo et al., 2012; Helliwell & Putnam, 2004; Nannestad, 2008; Portela et al., 2013; Puntscher et al., 2015; Sønderskov & Dinesen, 2016), the vast majority of studies did not analyze causal pathways, but rather relied on theoretical assumptions. Studies examining causality only analyzed individual data with mixed results (e.g., Daskalopoulou, 2019; Sønderskov & Dinesen, 2016). Theories of social and institutional trust however, have always considered trust as having individual and collective properties (e.g., Delhey & Dragolov, 2016; Putnam, 2001; Putnam et al., 1994), with social mechanisms on the country-level being at least as important to explain trust as individual determinants (see, Newton, 2004). Therefore, social mechanisms on the country-level can be distinct from those on the individual level, which can lead to different results (e.g., Schwartz, 1994). Further, trust on the collective level is qualitatively distinct from the individual level, thus justifying its utility as a distinct concept. Social trust on the individual level measures one´s trust in other people, while on the aggregate level it quantifies the climate of trust in one´s environment. As shown by Glatz and Eder (2020), living in an environment with high social trust is more beneficial for subjective well-being as compared to individual social trust. The same argument could hold for institutional trust, which can be interpreted as an indicator of the quality of institutions on the aggregate country-level (see, Mishler & Rose, 2001). For this reason, we aimed to extend previous research by examining the causal structure between (1) social trust and institutional trust, (2) social trust and subjective well-being and (3) institutional trust and subjective well-being by using longitudinal data on the country-level provided by the European Social Survey. In the following, we will describe the theoretical and empirical relation between social and institutional trust, followed by the theoretical and empirical relation of social and institutional trust with subjective well-being. It should be noted that theoretical models on this topic often do not explicitly differentiate between the individual- and the country-level. Therefore, we review both types of theories and discuss different implications in the discussion, after reporting methods and results of this study.

2 Theoretical and Empirical Relation Between Social and Institutional Trust

Social trust, on the one hand, is the touchstone of social capital as it reflects generalized reciprocity (Putnam, 2001). “I´ll do this for you now, without expecting anything immediately in return and perhaps without even knowing you, confident that down the road you or someone else will return the favor” (Putnam, 2001: 134). The core idea behind this effect is that social trust fosters social cohesion (see, Delhey & Dragolov, 2016). Institutional trust, on the other hand, is conceptually distinct from social trust as it includes trust in governments, political authorities or other social institutions, and serves as an indicator of the quality of institutions (see, Mishler & Rose, 2001; Nannestad, 2008; Sonderskov & Dinesen, 2014).

While social and institutional trust are conceptually distinct from each other (Putnam, 2001: 137), various scholars developed theoretical models addressing how these concepts might be interrelated with each other (Mishler & Rose, 2001; Nannestad, 2008; Putnam et al., 1994; Rothstein & Stolle, 2008). As reviewed by Nannestad (2008), high-quality institutions can diminish the risk associated with trusting others by setting appropriate rules and laws as well as establishing trust-friendly norms, for example, by preventing corruption or facilitating transparency. High-quality institutions are also of great importance for fairness and evenhandedness within a society, thus preventing underprivileged groups to believe that institutions serve mainly the interests of privileged individuals. Rothstein and Stolle (2008) additionally argued that institutions, primarily of law and order, are responsible to detect, stop or punish those who do not follow the law and therefore, those who cannot be trusted. If those institutions are perceived as well-functioning and fair, individuals will “have good reason to refrain from acting in a treacherous manner and thus conclude that most people can be trusted” (Rothstein & Stolle, 2008: 445–446). Summing up, one strand of theories explains institutional trust as a cause of social trust, as high-quality institutions support an environment fostering trust in other people, for example, through rules, norms or more fairness and evenhandedness across a society. A second strand of theories argues that trust in (political) institutions is merely an extension of social trust and deeply rooted in cultural norms (Mishler & Rose, 2001). Based on this assumption, social trust is a preliminary of institutional trust, as trust in other people leads to more trust in smaller civic associations and further in bigger institutions, forming a virtuous cycle of trust (Putnam et al., 1994).

Although multiple studies showed a correlation between social and institutional trust on the cross-sectional level (Dinesen & Bekkers, 2017), only few studies investigated its causal relation. Using instrumental variables, Daskalopoulou (2019) analyzed the causality between social and institutional trust in Greece during the economic crisis. She concluded that social trust positively affects institutional trust, while institutional trust negatively affects social trust, although this latter association seems to be driven mainly through trust in politicians. By utilizing the instrumental variable approach in the US, Brehm and Rahn (1997) concluded that the effect of institutional trust on social trust is substantially stronger, while Mishler and Rose (2001) found no relationship between social and institutional trust in post-communist countries. Thus, contradictory findings could also be traced back to the selection of countries and time periods in previous studies.

The instrumental variable-approach requires to identify an external (instrumental) variable related with the predictor, but unrelated with the criterion, which makes this approach questionable because meaningful instrumental variables are hard to find (Bound et al., 1995; Sønderskov & Dinesen, 2016). The other path to investigate a causal relation is by utilizing longitudinal data. By using a cross-lagged panel model, Sønderskov and Dinesen () analyzed individual panel data from Denmark and found a causal effect of institutional trust on social trust, but not vice versa. Although they rigorously examined two time-lags as well as fixed effects to account for unobserved heterogeneity in a different model, their analysis still shows some weaknesses since they did not account for differences between individuals (random intercepts), which could distort the results, especially since social- and institutional trust are rather time-stable concepts (Glatz & Eder, 2020; Hamaker et al., 2015).

3 Theoretical and Empirical Relation of Subjective Well-Being with Social and Institutional Trust

Importantly, numerous studies point to a positive impact of social and institutional trust on subjective well-being, with the implicit assumption that the former impacts the latter. Kroll (2008) argues that high institutional trust can foster subjective well-being as a subjective measure of the quality of regional institutions, thus preventing to feel powerless and helpless within the society. This general assumption that “good institutions” increase happiness among its citizens is widespread across the literature (Frey, 2008). Conversely, high life satisfaction could increase the legitimacy of political regimes and further foster democracy as argued by Inglehart (1999). Empirically, Hudson (2006) reported a causal effect from institutional trust to life satisfaction in Europe using cross-sectional individual data, while Fu (2018) showed a causal effect from collective institutional trust to individual subjective well-being in China using instrumental variables. Both studies however, did not analyze reverse causality.

Social trust strengthens social cohesion across a society and also facilitates the formation of dense social networks, which have intrinsic value to people and could thus increase subjective well-being (Delhey & Dragolov, 2016; Helliwell & Putnam, 2004: 1436). Further, living in a high trusting environment can elicit a sense of belonging to the community, which itself is an innate human need and thus may increase subjective well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; see, Lu et al., 2019). However, as previous studies have shown, happier individuals spend more time socializing compared to less happy people (Diener & Seligman, 2002; Mehl et al., 2010). Since social contacts and social trust are mutually reinforcing (Growiec, 2009), a reverse causal relation, running from subjective well-being to social trust, seems likely. Empirically, Kuroki (2011) as well as Lu et al. (2019) reported a positive effect of social trust on subjective well-being in Japan and China by using instrumental variables. However, they did not examine causality from subjective well-being to social trust. Guven (2011), on the other hand, used individual longitudinal data from Germany and showed that happiness could predict future social trust within a period of 20 years. He as well, did not examine the opposite causal pathway.

4 The Present Study

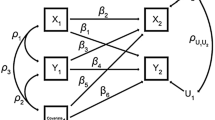

Summarizing, there are theoretical explanations for causal pathways in every direction between the three concepts of interest as reviewed above. Empirical studies so far showed causal pathways in both directions between social and institutional trust, between social trust and subjective well-being, and between institutional trust and subjective well-being (see, Fig. 1). Based on this review, we are hesitant to formulate clear-cut hypotheses, since empirical evidence for any direction on the aggregate level is vague. Therefore, we formulate the following research questions:

-

What is the causal relation between social trust and institutional trust on the country-level?

-

What is the causal relation between social trust and subjective well-being on the country-level?

-

What is the causal relation between institutional trust and subjective well-being on the country-level?

5 Method

For this study, we used aggregate country-level data based on the European Social Survey (ESS). The ESS is conducted every two years via face-to-face interviews and consists of a core module and a rotating module, which changes every two years. The core module contains sociodemographic variables as well as items to measure trust and subjective well-being. In the first wave of the ESS in 2002, 22 countries participated in the survey. Fifteen of these countries participated in every wave of the ESS since then and three countries skipped not more than one wave. We used all current available ESS data starting from the first wave in 2002 up to the latest release of the ninth wave in 2018.Footnote 1 In order to reduce biases due to different sample sizes between countries (see, Table 1), as well as due to sociodemographic differences in the respective samples compared to the population, we used a combination of the sociodemographic and sample weight provided by the ESS. In total, the ESS dataset consists of 217 observations from 30 countries nested in nine time-points.Footnote 2

We used multilevel bivariate cross-lagged models for analysis (as described below), which aimed to regress the predictor in t = 0 on the criterion in t = 1. To keep the gaps between t = 0 and t = 1 uniform, we only used gaps of two years, or one wave in the ESS. Moreover, although there was a total of 217 observations, we could only utilize a smaller number since preceding numbers for a respective time-point are mandatory. For example, although we have information about the criterion in t = 1 in 2002, we have no information about the predictor in t = 0 since the survey did not start before 2002. That said, for Austria for example, we could only utilize six observations (´02–´04, ´04–´06, ´06–´08, ´08–´10, ´14–´16, ´16–´18) due to the mentioned constrains. This leads to an effective sample of 175 observations for the multilevel bivariate cross-lagged analysis.

In this study, we exclusively analyzed data on the country level based on the ESS. Since we do not extrapolate the results to a specific country group population, the sample in this study represents the population. Therefore, we focused on resulting effect estimates and the respective credibility intervals instead of significance testing (Lucas, 2014).

5.1 Social and Institutional Trust

In the ESS, social trust is measured with three items while institutional trust is measured with seven items, which are part of the survey in every wave (see, Table 2). We performed a principal axis factor analysis with varimax rotation for every ESS round to investigate the underlying factors behind the items. Factor loadings for social trust reached a minimum of 0.78. For institutional trust, factor loading reached a minimum of 0.66 and a minimum of 0.70 after the exclusion of “trust in police” (see, Table 2). All exploratory factor analyses yielded two factors with Eigenvalues ≥ 1 and a minimum variance explanation of 64%, representing the factors “social trust” and “institutional trust”. Additionally, we examined measurement invariance for social- and institutional trust as well as subjective well-being using multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (e.g., Cieciuch et al., 2019; see Appendix 1). Based on this analysis, we calculated the mean for all three social trust variables, as well as the mean for six out of the available seven institutional trust variables after excluding “trust in the police” due to low factor loadings. Both social and institutional trust are measured on a scale from 0–10.

5.2 Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being is composed of affective and cognitive aspects. While the affective component is captured by the assessment of happiness, the cognitive component is captured by life satisfaction (Diener et al., 2012). The ESS includes one item for each component (see, Table 2), ranging from “0” (extremely unhappy/dissatisfied) to “10” (extremely happy/satisfied) on a 11-point scale. As both items measure one unique aspect of the same latent factor (Diener & Ryan, 2009), we calculated the mean of both items to measure subjective well-being. The internal consistency of subjective well-being was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.83; see also, Glatz & Eder, 2020). Due to the 0–10 scale, we assumed a metric scale level of the used items to measure social trust, institutional trust and subjective well-being, respectively. However, we encourage the ESS team to use item response theory (see Embretson & Reise, 2013) in the future to empirically test this assumption.

5.3 Procedure/Model

Because “true” causality can only be detected in a controlled experimental setting, we aimed for causal interpretation by using a multilevel bivariate cross-lagged model as described below. This method, however, has shortcomings, which cannot be circumvented by using longitudinal data, since hidden confounding variables can lead to spurious causation. A confounding variable could, for example, lead to higher levels of institutional trust in t = 0 (while not affecting social trust in t = 0) and further to higher levels of social trust in t = 1, inducing a spurious causation. However, we countered this problem by controlling for the logarithm of GDP per capita (log2 of GDP per capita) and the unemployment rate (for both source: World Bank) as prominent impact factors for several constructs, including social and institutional trust as well as subjective well-being (e.g., Bjørnskov, 2012; Dincer & Uslaner, 2010; Glatz & Eder, 2020; Mikucka et al., 2017). We also considered the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) as control variable but did not include it into the model due to high multicollinearity with the log2 of GDP per capita.

Since we are dealing with a rather small sample, but with many time points as depicted in Table 1 and described above, we applied a multilevel bivariate cross-lagged model as described by Schuurman et al. (2016). As noted by Hamaker et al. (2015)and Schuurman et al. (2016), it is necessary to distinguish the (trait like) between- from the (state like) within effect to get unbiased results. To fit the model, we used the equation as shown below. Of note, y is decomposed into a between part for each country i (by = y̅i) and a within part for each country i and time point t (wy = yit—y̅i) (see, Bell et al., 2018). Thus, we aimed to explain y1 of country i in time t with the cross-lagged effect of wy2 of country i in time t − 1 after controlling for by1 of country i, the autoregressive effect of wy1 of country i in time t − 1 and the covariates log2gdp and unemployment in time t of country I, respectively. According to Finch et al. (2019) and due to the small sample size, we only estimated one lag of t − 1 of the cross-lagged as well as the autoregressive part of the equation, since time is measured in fixed intervals of 2 years.

6 Formula

(a) y1ti = α1 by1i + φ1 wy2it − 1 + β1 wy1it − 1 + δ1 log2gdpti + γ1 unemployment ti + ε1ti.

(b) y2ti = α2 by2i + φ2 wy1it − 1 + β2 wy2it − 1 + δ2 log2gdpti + γ2 unemployment ti + ε2ti.

Note: A reading example of the formula with the empirical data is shown in the notes of Tables 4 and 5.

As suggested by Schuurman et al. (2016), we used Bayesian statistic to estimate the models. For this matter, we used the software package brms (Bürkner, 2018; vers. 2.14.4) in R (R Core Team, 2014), which allows to fit two equations simultaneously and thus to control for correlating residual variances between y1ti and y2ti. Since previous empirical research provided evidence for causal effects from social trust to institutional trust (Daskalopoulou, 2019) and reverse (Brehm & Rahn, 1997; Sønderskov and Dinesen 2014, 2016), from social trust to subjective well-being (Kuroki, 2011; Lu et al., 2019) and reverse (Guven, 2011), as well as from institutional trust to subjective well-being (Fu, 2018; Hudson, 2006), we used weak informative priors for the respective cross-lagged effects in our analysis as suggested in the literature (see, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg et al., 2017) by setting those population-level (fixed) effects to an expected mean of 0.20 with a standard deviation of 0.60. However, sensitivity analyses suggested that the results were comparable when using non-informative (default) priors, since the respective effects did not differ by more than 0.01 points.Footnote 3 In addition to controlling for random intercepts between countries, we estimated random slopes of the cross-lagged effects, which are reported in Appendix 2.

We also considered a multilevel vector autoregression (VAR) model for our analysis. Compared to this model, the bivariate cross-lagged models allow us to (1) control for residual correlations between the respective outcome variables, to (2) control for covariates which could distort the results, and (3) to additionally include informative priors as described above. Therefore, we decided to use the multilevel bivariate cross-lagged models for the main analysis. Nonetheless, we additionally analyzed multilevel VAR models using the R package “mlVAR” (Epskamp et al. 2021). As suggested by the authors, we set the contemporaneous estimation to “fixed”. We additionally set the temporal estimation to “fixed” such that only the intercept is random. We first ran the analysis with the original variables “social trust”, “institutional trust” and “subjective well-being”. These original variables represent the respective mean of the construct for each country in each time-point. We additionally ran the analysis with the within-variables of the respective constructs as suggested by Schuurman et al. (2016) and Hamaker et al. (2015). The results of both variations of the multilevel VAR models were basically the same. Importantly, the results were similar to the multilevel bivariate cross-lagged models and led to the same interpretations and conclusion. Regarding the causal effect from social trust to subjective well-being, we found minor differences as reported in the results section. Results of the multilevel VAR models are available upon request from the first author.

6.1 Robustness Test

Within the timeframe of the ESS, the global financial crisis reached Europe in 2007 (see, Alessi et al., 2018), leading to an economic downturn, rising unemployment and a sovereign debt crisis. This exogenous shock also affected institutional trust (Glatz & Eder, 2020) and subjective well-being (Alessi et al., 2018), which could distort our results. For this reason, we provide a robustness test (see, Table 5) in which we removed the time period of the financial crisis. First, we removed the transitions from 2006 to 2008 from the analysis, reducing the sample to effectively 152 observations. In a second step, we additionally removed the transitions from 2008 to 2010 as some countries needed several years to recover from the financial crisis. This reduced the effective sample size to 125 observations. Furthermore, in 2015, the "refugee crisis" arose in Europe with about one million refugees arriving in Europe (Georgiou & Zaborowski, 20172017), which received great media attention. Therefore, in a last step, we also deleted both periods after the beginning of the refugee crisis from the main analysis, namely transitions from 2014 to 2016 as well as from 2016 to 2018, which reduced the sample to 135 observations.

7 Results

We start with descriptive statistics for all countries (see, Table 3) before moving to the main analysis of the multilevel bivariate cross-lagged models (see, Table 4) and subsequently to the robustness test (see, Table 5). For social trust, institutional trust and subjective well-being, within fluctuations for each country are reported. Hence, the mean scores for the respective constructs equal zero. Considering the standard deviations, social trust fluctuated the least over time, followed by subjective well-being, while institutional trust evidenced the strongest fluctuation over time. There was a positive development of social trust over time, starting at − 0.15 points of the general mean and developing to + 0.13 points in 2018. Accordingly, subjective well-being showed a similar positive development from − 0.09 points compared to the general mean in 2002 up to + 0.23 points in 2018. Institutional trust, on the other hand, did not show a steady development, but rather fluctuated disjointed over time. GDP per capita increased as expected, while unemployment showed some fluctuations over time.

The main findings of the multilevel bivariate cross-lagged models are presented in Table 4 and depicted in Fig. 2. First, the autoregressive pathways indicate the “carry-over” or “momentum” effect of a certain construct. Thus, if a country reports a score above-average in t = 0, this “momentum” effect would lead to a score above-average in t = 1 as well. This holds true for all constructs, namely social trust, institutional trust and subjective well-being, although this effect was most pronounced for subjective well-being.

Causal paths between social trust, institutional trust and subjective well-being. Horizontal lines show autoregression of t − 1 on t for the same variable. Cross-lagged lines show the cross-lagged effect of y2 in t − 1 on y1 in time t (and reverse). B coefficients (with standard errors in parenthesis) are reported, credibility intervals are reported in Table 4. All variables are scaled from 0 to 10

Next, the main findings of this study are reported, namely the cross-lagged effects between the three constructs. As shown in the first model, there was no substantial effect from social trust in t = 0 to institutional trust in t = 1. Conversely, a small negative effect from institutional trust to social trust with a B of − 0.12 was found, which was consistent across countries (see, “random slope” in Table 4 as well as Appendix 2). The second model suggested a mutually reciprocal relation between social trust and subjective well-being, since both constructs in t = 0 predicted the other one in t = 1. The causal pathway seemed to be stronger from subjective well-being to social trust (B = 0.22), as compared to the path from social trust to subjective well-being (B = 0.15). Again, this effect was consistent across countries, because positive effects for those causal pathways were evident for all countries (depicted in Appendix 2). The third and last model showed no substantial effect from subjective well-being to institutional trust. Similar to the first model, there was a small negative causal pathway from institutional trust to subjective well-being, which was consistent across countries (see, Appendix 2). The multilevel VAR models also showed consistent results.

Social trust (y1): y1ti = α1 Between social trust + φ1 Within institutional trust t − 1 + β1 Within social trust t − 1 + δ1 log2gdpti + γ1 unemploymentti.

Institutional trust (y2): y2ti = α2 Between institutional trust + φ2 Within social trust t − 1 + β2 Within institutional trust t − 1 + δ2 log2gdpti + γ2 unemploymentti.

Finally, Table 5 shows the results of the robustness tests, which excluded the time periods of the financial crisis as well as of the refugee crisis as exogeneous shocks. All three robustness tests showed similar results as the main analyses. Specifically, regarding institutional trust, there was no causal pathway from social trust and subjective well-being, respectively, to institutional trust, but a small negative effect from institutional trust to both social trust and subjective well-being. Further, all robustness tests suggested a causal pathway from subjective well-being to social trust. On the other hand, all three robustness tests showed no clear sign of a causal effect from social trust to subjective well-being. In this case, the multilevel VAR models paints a slightly different picture with positive effects from social trust to subjective well-being in the first (1) and second (2) robustness test (B = 0.25, SE = 0.14). Confidence intervals, however, show that there is still a > 5% chance that this effect equals (less than) zero (CI: −0.02 to 0.52). In line with the main analysis, the third (3) robustness test of the multilevel VAR models shows no positive effect from social trust to subjective well-being (B = 0.07, SE = 0.11). Based on these results, we cannot infer a causal effect from social trust to subjective well-being, although the results are ambiguous in this manner and the interpretation remains inconclusive.

Social trust (y1): y1ti = α1 Between social trust + φ1 Within institutional trust t − 1 + β1 Within social trust t − 1 + δ1 log2gdpti + γ1 unemploymentti.

Institutional trust (y2): y2ti = α2 Between institutional trust + φ2 Within social trust t − 1 + β2 Within institutional trust t − 1 + δ2 log2gdpti + γ2 unemploymentti.

8 Discussion

By using multilevel bivariate cross-lagged models, the goal of this research was to disentangle the causal pathways between social trust, institutional trust and subjective well-being on the country level by using longitudinal data from the ESS. In summary, we found no causal pathway from social trust and subjective well-being, respectively, to institutional trust. On the other hand, we found small but negative causal pathways from institutional trust to both social trust and subjective well-being. Further, we found a causal pathway from subjective well-being to social trust in the main analysis as well as in the robustness tests. Conversely, we found a smaller causal effect from social trust to subjective well-being in the main analysis, which however vanished in the robustness tests. An additional multilevel VAR analysis showed some support for a causal effect from social trust to subjective well-being in the robustness tests. Based on this inconclusive empirical evidence, however, we cannot infer a causal effect from social trust to subjective well-being on the country-level.

While several theories argued that social trust predicts institutional trust (Mishler & Rose, 2001; Putnam et al., 1994) and vice versa (Nannestad, 2008; Rothstein & Stolle, 2008), we only found a minor, but negative causal pathway from institutional trust to social trust. It should be noted however, that these theories are mainly based on the individual level. Studies on the individual level reported mixed results regarding the causal relation between social- and institutional trust by utilizing instrumental variables or cross-lagged panel analysis (Brehm & Rahn, 1997; Daskalopoulou, 2019; Mishler & Rose, 2001; Sønderskov & Dinesen, 2016). While psychological aspects like personality traits, amongst others, may play a role at the individual level, those individual effects seem to vanish at the country level. Arguably, political events as well as economic outcomes could be the main driver to explain institutional trust at the country level (e.g., Bonasia et al., 2016; Glatz & Eder, 2020; Roth et al., 2011). Despite a societal consent about “good” economic outcomes like low unemployment, expectations on (political) institutions seems to differ between individuals (Mishler & Rose, 2001). Certain political interventions in t = 0 could be welcomed by one group, which strengthens their trust in these institutions, but simultaneously disappoint another group and betray their trust, which could also be the reason for the fluctuating and non-steady development of institutional trust over time. This potential exogenous driver of institutional trust could be the reason why institutional trust could not be predicted and only small negative effects from institutional trust to social trust and subjective well-being on the country level were found.

Regarding the causal relation between social trust and subjective well-being, one strand of theories suggests that social trust fosters social cohesion (Delhey & Dragolov, 2016), which facilitates the formation of dense social networks and thus, increases subjective well-being (Helliwell & Putnam, 2004: 1436). This theoretical assumption is prevalent in the quality-of-life research, since most studies assume that social trust affects subjective well-being (e.g., Glatz & Eder, 2020; Helliwell & Putnam, 2004; Portela et al., 2013; Puntscher et al., 2015). Our data only partially support this assumption. Hence, we cannot assume causality from social trust to subjective well-being. On the other hand, we found an opposite causal pathway from subjective well-being to social trust at the country level. Therefore, our data suggest that a happy society could lead to a higher trust amongst its residents, but not necessarily the other way around. This finding is in line with previous research, which showed that happy individuals spend more time socializing (Diener & Seligman, 2002; Mehl et al., 2010), while social contacts and social trust are mutually reinforcing each other (Growiec, 2009). This is also in accordance with Guven (2011), who showed that happiness predicted future social trust in 20 years using individual panel data.

Regarding institutional trust and subjective well-being, there are theoretical explanations for causal effects in both directions (see, Kroll, 2008; Frey, 2008; Inglehart, 1999) and empirical evidence exists for a causal effect from institutional trust to subjective well-being at the individual level (Fu, 2018; Hudson, 2006). As mentioned above, we found no substantial causal pathway between these two constructs on the country level, which is in line with Glatz and Eder (2020), who analyzed this relation using longitudinal data at the country level and found no effect from institutional trust to subjective well-being. This result points to a different mechanism between the country- and individual-level as described above.

By interpreting our results, we have to take certain limitations into account. First, although longitudinal data could be used to approach causality, “true” causality can only be derived in an experimental setting. Possibly, confounding variables could affect the predictor in the past while subsequently affecting the criterion in the present, which would lead to distorted results. Second, since we used data from the ESS, the generalizability to other countries is limited. Third, the aim of this study was to examine causal pathways on the aggregate country level. Thus, results and mechanism can potentially differ at the individual level. Finally, albeit the ESS provides a large amount of observations, the time frame is limited to 2002 to 2018, which allows to infer short-term causal pathways between the constructs of interest, while the long-term causal pathways remain speculative. Thus, historical questions, such as whether social trust is a necessary prerequisite for building institutional trust, cannot be answered (e.g., Mishler & Rose, 2001).

Despite these limitations, this study offers a new and unique insight into the causal pathways and mechanisms between social trust, institutional trust and subjective well-being. At the country level, we found no substantial causal pathway from institutional trust to social trust and subjective well-being or reverse. However, we found a causal link from subjective well-being to social trust, implying that a happy society could lead to a (socially) trusting society. On the other hand, the data do not fully support the assumption that social trust leads to higher subjective well-being amongst a society. Overall, our findings support the view that neither social nor institutional trust substantially affect subjective well-being at the country level, but rather reflect independent facets to assess the quality of life of a society as already implemented by the OECD with its better life index (Durand, 2015), amongst others.

Notes

The latest release (retrieved on 19. October 2020) of the 2018 ESS wave 9 includes 27 countries. Three more countries will be added to a later date.

Numbers refer to the already prepared dataset for this study (see notes of Table 1).

With one exception where the b changed 0.03 points (see Footnote 4 below), which however did not alter interpretation of the data.

References

Alessi, L., Benczur, P., Campolongo, F., Cariboni, J., Manca, A. R., Menyhert, B., & Pagano, A. (2018). The resilience of EU Member States to the financial and economic crisis. What are the characteristics of resilient behaviour? (No. JRC111606). Joint Research Centre (Seville site).

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bell, A., Jones, K., & Fairbrother, M. (2018). Understanding and misunderstanding group mean centering: A commentary on Kelley et al.’s dangerous practice. Quality and Quantity, 52(5), 2031–2036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0593-5

Benz, A. (2002). Vertrauensbildung in mehrebenensystemen. In R. Schmalz-Bruns & Z. Reinhard (Eds.), Politisches vertrauen soziale grundlagen reflexiver kooperation (pp. 275–291). Nomos: Baden-Baden.

Bjørnskov, C. (2012). How Does social trust affect economic growth? Southern Economic Journal, 78(4), 1346–1368. https://doi.org/10.4284/0038-4038-78.4.1346

Bonasia, M., Canale, R. R., Liotti, G., & Spagnolo, N. (2016). Trust in institutions and economic indicators in the eurozone: The role of the crisis. Engineering Economics, 27(1), 4–12.

Bound, J., Jaeger, D. A., & Baker, R. M. (1995). Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous explanatory variable is weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 443–450.

Brehm, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 999. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111684

Bürkner, P. C. (2018). Advanced bayesian multilevel modeling with the R package brms. The R Journal, 10(1), 395–411. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-017

Calvo, R., Zheng, Y., Kumar, S., Olgiati, A., & Berkman, L. (2012). Well-being and social capital on planet earth: cross-national evidence from 142 countries. PLoS ONE, 7(8), e42793. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042793

Cieciuch, J., Davidov, E., Schmidt, P., & Algesheimer, R. (2019). How to obtain comparable measures for cross-national comparisons. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 71(1), 157–186.

Daskalopoulou, I. (2019). Individual-level evidence on the causal relationship between social trust and institutional trust. Social Indicators Research, 144(1), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2035-8

Delhey, J., & Dragolov, G. (2016). Happier together. Social cohesion and subjective well-being in Europe: happier together-cohesion and SWB. International Journal of Psychology, 51(3), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12149

Diener, E. (2009). Subjective well-being. The Science of Well-Being, 37(1), 11–58.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), The science of happiness and life satisfaction. (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0017

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2015). National accounts of subjective well-being. American Psychologist, 70(3), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038899

Diener, E., & Ryan, K. (2009). Subjective well-being: a general overview. South African Journal of Psychology, 39(4), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630903900402

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415

Dincer, O. C., & Uslaner, E. M. (2010). Trust and growth. Public Choice, 142(1–2), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9473-4

Dinesen, P. T., & Bekkers, R. (2017). The foundations of individuals’ generalized social trust: A review. In P. A. M. Van Lange, B. Rockenbach, & T. Yamagishi (Eds.), Trust in social dilemmas. Series in human cooperation. (Vol. 2). New York: Oxford University Press.

Durand, M. (2015). The OECD better life initiative: How’s life? and the measurement of well-being. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(1), 4–17.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? some empirical evidence. Nations and households in economic growth (pp. 89–125). Academic Press: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-205050-3.50008-7

Embretson, S. E., & Reise, S. P. (2013). Item response theory. Psychology Press.

Epskamp, S., Deserno, M. K., Bringmann, L. F. (2021). mlVAR: Multi-level vector autoregression. R package version 0.5. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mlVAR

Finch, W. H., Bolin, J. E., & Kelley, K. (2019). Multilevel modeling using R. Boca Raton: Crc Press.

Fischer, R., & Karl, J. A. (2019). A primer to (cross-cultural) multi-group invariance testing possibilities in R. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1507.

Frey, B. S. (2008). Happiness: A revolution in economics. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262062770.001.0001

Fu, X. (2018). The Contextual effects of political trust on happiness: Evidence from China. Social Indicators Research, 139(2), 491–516.

Georgiou, M., & Zaborowski, R. (2017). Media coverage of the “refugee crisis”: A cross-European perspective. London: Council of Europe.

Glatz, C., & Eder, A. (2020). Patterns of trust and subjective well-being across europe: New insights from repeated cross-sectional analyses based on the european social survey 2002–2016. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02212-x

Growiec, K. (2009). Zwi˛azek mi˛edzy sieciami społecznymi a zaufaniem społecznym—mechanism wzajemnego wzmacniania? [The relationship between social networks and social trust: A mutually reinforcing mechanism]? Psychologia Społeczna, 4(1–2), 10.

Guven, C. (2011). Are happier people better citizens?: Are happier people better citizens? Kyklos, 64(2), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2011.00501.x

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435–1446. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1522

Hudson, J. (2006). Institutional trust and subjective well-being across the EU. Kyklos, 59(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00319.x

Inglehart, R. (1999). Trust, well-being and democracy. In M. E. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and Trust (1st ed., pp. 88–120). Cambridge: University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511659959.004

Kroll, C. (2008). Social capital and the happiness of nations: the importance of trust and networks for life satisfaction in a cross-national perspective. New York: P. Lang.

Kuroki, M. (2011). DOES social trust increase individual happiness in japan?*. Happiness and Trust. Japanese Economic Review, 62(4), 444–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5876.2011.00533.x

Lu, H., Tong, P., & Zhu, R. (2019). Longitudinal evidence on social trust and happiness in china: causal effects and mechanisms. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00159-x

Lucas, S. R. (2014). An inconvenient dataset: Bias and inappropriate inference with the multilevel model. Quality and Quantity, 48(3), 1619–1649.

Macchia, L., & Plagnol, A. C. (2018). Life satisfaction and confidence in national institutions: Evidence from South America. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9606-3

Mehl, M. R., Vazire, S., Hollera, S. E., & Clark, C. S. (2010). Eavesdropping on happiness: Well-being is related to having less small talk and more substantive conversations. Psychological Science, 21(4), 539–541.

Mikucka, M., Sarracino, F., & Dubrow, J. K. (2017). When does economic growth improve life satisfaction? Multilevel analysis of the roles of social trust and income inequality in 46 countries, 1981–2012. World Development, 93, 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.002

Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2001). What are the origins of political trust?: Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comparative Political Studies, 34(1), 30–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414001034001002

Mulder, J. D., & Hamaker, E. L. (2020). Three extensions of the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28, 1–11.

Nannestad, P. (2008). What have we learned about generalized trust, if anything? Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 413–436. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135412

Newton, K. (2004). Social trust: Individual and cross-national approaches. Portugese Journal of Social Sciences, 3(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1386/pjss.3.1.15/0

Nussbaum, M. C. (2001). The fragility of goodness: luck and ethics in Greek tragedy and philosophy. Cambridge: University Press.

Oishi, S., & Schimmack, U. (2010). Culture and well-being: A new inquiry into the psychological wealth of nations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375561

Portela, M., Neira, I., & del Salinas-JiménezM., M. (2013). Social capital and subjective wellbeing in Europe: A new approach on social capital. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 493–511.

Puntscher, S., Hauser, C., Walde, J., & Tappeiner, G. (2015). The impact of social capital on subjective well-being: a regional perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(5), 1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9555-y

Putnam, R. D. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community (1. touchstone ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster.

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. (1994). Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy (5. print., 1. Princeton paperback print.). Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

R Core Team. (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Roth, F., Nowak-Lehmann, F. and Otter, T. (2011). Has the financial crisis shattered citizens’ trust in national and European governmental institutions? CEPS Working Document, No. 343 (June). Brussels: CEPS.

Rothstein, B., & Stolle, D. (2008). The State and social capital: An institutional theory of generalized trust. Comparative Politics, 40(4), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041508X12911362383354

Schuurman, N. K., Ferrer, E., de Boer-Sonnenschein, M., & Hamaker, E. L. (2016). How to compare cross-lagged associations in a multilevel autoregressive model. Psychological Methods, 21(2), 206.

Schwartz, S. (1994). The fallacy of the ecological fallacy: The potential misuse of a concept and the consequences. American Journal of Public Health, 84(5), 819–824. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.84.5.819

Selig, J. P., & Little, T. D. (2012). Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In B. Laursen, T. D. Little, & N. A. Card (Eds.), Handbook of developmental research methods (pp. 265–278). The Guilford Press.

Sonderskov, K. M., & Dinesen, P. T. (2014). Danish exceptionalism: Explaining the unique increase in social trust over the past 30 years. European Sociological Review, 30(6), 782–795. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu073

Sønderskov, K. M., & Dinesen, P. T. (2016). Trusting the state, trusting each other? The effect of institutional trust on social trust. Political Behavior, 38(1), 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9322-8

Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, M., Peeters, M., Depaoli, S., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Where do priors come from? Applying guidelines to construct informative priors in small sample research. Research in Human Development, 14(4), 305–320.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Measurement invariance was calculated using multigroup confirmatory factor analysis for 217 groups (countries_x_time-points) (as depicted in Table 1). Running this MCFA for 217 groups resulted in optimization problems due to the large sample size, which is why we arranged those groups into four country groups. We calculated models including social trust (three indicators), institutional trust (six indicators) and subjective well-being (two indicators) as described in the method section and compared the unconstrained models with metric models (equal loadings across groups). Although log-likelihood results show significant differences between the models, implying that measurement invariance is not given, this test is prone to high sample sizes (Fischer & Karl, 2019). Therefore, we additionally report the fit indices CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR as well as the relative change between the configural unconstrained model and the metric model. As depicted, the metric model only shows negligible differences to the unconstrained configural model regarding CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR, which is why we assume measurement invariance and continued the analysis.

CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Chi2 | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Country group (1/4) | Configural model | 0.87 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 59,534 | 124,035 |

Metric model | 0.86 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 63,923* | ||

Change model fit | Δ0.01 | Δ0.01 | Δ0.00 | Δ-4,389 | ||

Country group (2/4) | Configural model | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 18,684 | 80,347 |

Metric model | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 20,684* | ||

Change model fit | Δ0.00 | Δ0.00 | Δ−0.01 | Δ−2,000 | ||

Country group (3/4) | Configural model | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 13,154 | 81,953 |

Metric model | 0.95 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 15,672* | ||

Change model fit | Δ0.01 | Δ0.00 | Δ−0.01 | Δ−2,518 | ||

Country group (4/4) | Configural model | 0.94 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 20,638 | 98,404 |

Metric model | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 24,065* | ||

Change model fit | Δ0.01 | Δ0.00 | Δ−0.01 | Δ−3,427 |

Appendix 2

Random slopes of the cross-lagged effects for each country for the main analysis.

Outcome variable | Social Trust (y2) | Institutional Trust (y2) | SWB (y2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Predictor | Institutional Trust (y1 t − 1) | SWB (y1 t − 1) | Social Trust (y1 t − 1) | SWB (y1 t − 1) | Institutional Trust (y1 t − 1) | Social Trust (y1 t − 1) |

AT | − 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.10 | − 0.09 | 0.18 |

BE | − 0.09 | 0.21 | − 0.07 | 0.15 | − 0.08 | 0.14 |

BG | − 0.14 | 0.18 | − 0.02 | − 0.04 | − 0.11 | 0.14 |

CH | − 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.11 | − 0.08 | 0.14 |

CY | − 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.47 | − 0.12 | 0.08 |

CZ | − 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.06 | − 0.06 | 0.13 |

DE | − 0.07 | 0.24 | − 0.06 | − 0.06 | − 0.08 | 0.21 |

DK | − 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.00 | − 0.09 | − 0.10 | 0.14 |

EE | − 0.13 | 0.21 | − 0.03 | − 0.16 | − 0.11 | 0.17 |

ES | − 0.09 | 0.25 | − 0.13 | − 0.22 | − 0.10 | 0.09 |

FI | − 0.13 | 0.24 | − 0.05 | − 0.10 | − 0.09 | 0.12 |

FR | − 0.14 | 0.24 | − 0.08 | − 0.12 | − 0.10 | 0.14 |

GB | − 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.04 | − 0.03 | − 0.09 | 0.16 |

GR | − 0.13 | 0.18 | − 0.14 | 0.04 | − 0.06 | 0.07 |

HR | − 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.05 | − 0.07 | − 0.11 | 0.22 |

HU | − 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.15 | − 0.09 | 0.10 |

IE | − 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.04 | − 0.01 | − 0.08 | 0.17 |

IL | − 0.13 | 0.19 | − 0.03 | − 0.04 | − 0.10 | 0.14 |

IT | − 0.18 | 0.22 | − 0.02 | 0.03 | − 0.14 | 0.17 |

LT | − 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.08 | − 0.01 | − 0.05 | 0.28 |

LU | − 0.12 | 0.21 | − 0.02 | 0.01 | − 0.09 | 0.16 |

NL | − 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.05 | − 0.03 | − 0.07 | 0.18 |

NO | − 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.29 | − 0.10 | 0.14 |

PL | − 0.13 | 0.22 | − 0.04 | 0.08 | − 0.08 | 0.14 |

PT | − 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.00 | − 0.13 | − 0.09 | 0.20 |

RU | − 0.11 | 0.26 | − 0.09 | − 0.20 | − 0.09 | 0.11 |

SE | − 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.01 | − 0.03 | − 0.09 | 0.15 |

SI | − 0.21 | 0.23 | − 0.14 | − 0.16 | − 0.09 | 0.13 |

SK | − 0.13 | 0.09 | − 0.02 | − 0.63 | − 0.06 | 0.20 |

UA | − 0.11 | 0.27 | − 0.01 | 0.02 | − 0.10 | 0.11 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glatz, C., Schwerdtfeger, A. Disentangling the Causal Structure Between Social Trust, Institutional Trust, and Subjective Well-Being. Soc Indic Res 163, 1323–1348 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02914-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02914-9