Abstract

This paper compares the monetary and living standards approaches to poverty using Australian data for the period 2006–2017. The aim is to highlight the conceptual and empirical strengths and weaknesses of the two approaches and identify the similarities and differences that emerge when both are applied to examine what happened over the period and to a limited degree, why. The acknowledged limitations of estimating poverty rates by comparing household income with a poverty line have to a degree been addressed by developments in deprivation research that have generated estimates that are more directly related to living standards, more democratic and more credible. But this approach also has limitations, so its growing popularity need not signify the end of poverty line studies. This paper compares the two approaches, with specific attention paid to ensuring that the estimates are internally consistent over time and comparable at a point in time. Both show a consistent pattern of modest improvement in social disadvantage over the period examined, but they reveal different aspects of change. The monetary approach highlights the role of housing costs in driving changes in poverty, while the more nuanced explanation generated by estimates of deprivation provides detailed insights. The results suggest that each has a positive role to play in better understanding the nature of poverty and identifying the factors driving change over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Poverty research in high-income countries has long been dominated by a focus on income, but on-going concerns about its identification and measurement have undermined the credibility of estimated poverty rates and provided policy makers with an excuse to ignore them. However, measuring poverty remains important and will become more so under the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), which require all participating countries to: ‘reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions’ by 2030. This will require countries to develop their own poverty measures to assess their performance and does not preclude non-monetary measures. Australia is a signatory to the SDGs but currently seems a long way from developing its own measures and using them to assess its poverty reduction performance.

Australian poverty research remains dominated by income-based poverty line studies (see Rodgers et al., 2009; Saunders, 2017; Davidson et al., 2020; Azpitarte & Kalb, 2019) although considerable attention has recently been paid to exploring the dynamics and persistence of poverty using longitudinal data from the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey (Rodgers & Rodgers, 2009; Wilkins, 2017: Chapter 3) The HILDA data has also been used to develop multidimensional measures that draw on the concept of social exclusion (Azpitarte, 2014; Martinez & Perales, 2017; Scutella et al., 2009), or on Sen’s notion of capability (Sen, 1985)–see Bessell, 2015; Sollis, 2019).Footnote 1 Interest in Australian poverty reflects its heavily targeted social security system that provides safety net social assistance benefits rather than the income-replacing earnings-related benefits that are a feature of many European social insurance schemes. However, successive governments have been reluctant to acknowledge that poverty exists or develop social policies designed to combat it (however defined) and the monetary approach seems incapable of generating the evidence needed to convince policy makers of the need to act.Footnote 2

The living standards approach has addressed some of the limitations of the monetary approach to produce evidence that is intellectually more compelling and politically more credible. The consensual approach to measuring deprivation builds on pioneering work by Townsend (1979), has been popularised by Mack and Lansley (1985) and further refined in a series of studies (Gordon & Pantazis, 1997; Pantazis et al., 2006), culminating in the UK Poverty and Social Exclusion Study (UK-PSE) (Dermott & Main, 2018) that has been described as ‘hugely influential nationally and internationally’ (Bailey & Bramley, 2018: 1). The deprivation approach identifies those unable to achieve an acceptable standard of living, assessed using prevailing community norms and perceptions. Whereas the key component of the monetary approach is a poverty line, the deprivation approach identifies items that are widely seen as essential (or necessary, the terms are used interchangeably here) pre-conditions for inclusion and then establishes who does not have and cannot afford these items. A key difference is that whereas poverty lines are set and adjusted over time by experts, social necessities are identified by drawing on the experiences and attitudes of members of the community. Saunders et al. (2008) and Saunders and Wong (2012) have adapted and applied the consensual approach to Australia using data collected in specially designed surveys and a new deprivation module has been included in recent waves of the HILDA survey.Footnote 3

Unlike the monetary approach which presumes (but never demonstrates) that those with incomes below the poverty line are poor, those unable to afford essential items in the living standards approach are ‘in effect, excluded from ordinary living patterns and activities’ (Townsend, 1979: 31) and thus more demonstrably poor. The shift from available resources to observable outcomes injects estimates of deprivation with the credibility that poverty rates lack, making them harder to dismiss without questioning community views on what poverty means–to those who experience it, not to those who study it. By basing its measurement on a community consensus, the living standards approach is also more democratic and (arguably) less influenced by experts, and hence more likely to be heeded by policy makers wary about the motives of experts and about the vagaries of the poverty line.

Studies have developed a composite measure of ‘consistent poverty’ that includes both income poverty and material deprivation dimensions (see Nolan & Whelan, 1996; Maître, Nolan and Whelan, 2006; Saunders and Naidoo, 2009). These measures are consistent with the SDG poverty reduction targets, are incorporated into the EU social agenda and have been adopted in modified form in recent national efforts to combat poverty.Footnote 4 A common research finding is that the overlap between the monetary and living standards measures is low (see Perry, 2002; Hick, 2014; Saunders & Naidoo, 2019a, b), indicating that the two approaches reveal different aspects of the same underlying problem. However, the fact that the approaches are different indicates nothing about which is superior. It is, however, possible to examine these differences to shed light on the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach. This provides the motivation for this paper, which applies the monetary and living standards approaches to examine recent Australian experience. By holding the broad economic context and policy settings fixed and adopting a comparative perspective, the paper better highlights the weaknesses and contributions of each approach and provides a better understanding of the factors contributing to poverty and driving change.

The paper is organised as follows: Sect. 2 describes the conceptual and practical elements of the two approaches, specifically when applied to examine changes over time. Section 3 provides background information on the Australian experience and describes our data sources, methods and measures. Section 4 presents and compares the results showing how income poverty and material deprivation changed, and the implications of the findings are discussed and compared in the final section.

2 The Monetary and Living Standards Approaches

The three main criticisms of the monetary approach relate to the narrow focus of its income metric, the arbitrary nature of the poverty line and the use of the household as the unit of analysis. The significance of the first criticism depends on the use to which the estimates are to be put. If the aim is to identify who is most in need of additional income support, then the income metric is highly appropriate. If, however, the goal is to identify pockets of disadvantage in order to gain a broader understanding of its causes and consequences and guide a wider policy response, then a focus on income alone may be unduly narrow. The use of an income metric does thus not automatically imply that it is inappropriately narrow. The setting of the poverty line always requires a judgement to be made and will be criticised by those who favour an alternative. But most of these critics are opposed to any poverty line not just to a specific choice, and they rarely suggest an alternative. Their aim is to discredit poverty research altogether rather than raise concerns about any specific component. The force of this criticism is further eroded by Atkinson (1987), who shows that one can experiment with a range of poverty lines and test for stochastic dominance in the results. Even so, where the poverty is set determines the measured poverty rate but also affects the credibility of the estimates, but there is no agreed method for setting the line or for reaching a consensus on how to choose between alterative options.Footnote 5

The third weakness, relating to the choice of household as the unit of analysis raises several issues. These concern the relevance of the assumption of intra-household income sharing and the use of an equivalence scale to adjust incomes for differences in household need. The former assumption is known to be problematic although difficult to substantiate without new data, and there are questions about whether (and how) policy should seek to address unequal intra-household income sharing (which will vary between households). The equivalence adjustment conventionally uses a simplified scale that has widespread acceptance for being ‘reasonable’, albeit with little hard evidence to support it.Footnote 6 These assumptions, when combined with person-weighting, allow the percentage of individuals living in households with income below the poverty line to be estimated (the headcount poverty rate). However, no attempt is made to establish that those so identified are actually experiencing poverty. This has led agencies like the EU Statistical Office (Eurostat) to refer to the estimates as measuring the ‘risk of poverty’ rather than its existence (see Atkinson et al., 2017: 46).

The method used to measure deprivation is the consensual approach. It emerged and has evolved to address criticisms directed at Townsend’s original application (see Piachaud, 1981; McKay, 2004; Hick, 2012) and now embodies both methodological refinements (summarised by Gordon, 2006, 2017, 2018) and new ways of collecting, analysing and interpreting the data used to measure deprivation (see Hick, 2016).Footnote 7 They have produced new ways of identifying ‘socially perceived necessities’ and better establishing that their absence reflects a lack of affordability rather than individual choice or preference.Footnote 8 The main attraction of the consensual approach is its ability to identify items that attract majority support for being ‘essential for all’ in society at a particular point in time. However, Gutfleisch and Andreβ (2020) have noted that this is a demanding task because it requires people to abstract from their own views and experiences to reflect on and assess what others need–including others that they may have little in common with. Despite the difficulty, studies show that many items attract widespread support (often in excess of 90 per cent) for being ‘essential for all’. However, because these items reflect prevailing norms and attitudes, their identification should be revisited regularly to ensure it reflects contemporary views about minimal living standards. Such revision ensures that the approach is embedded in existing norms and practices and is thus relative in the sense envisaged by Townsend (1987).

Once the items that satisfy the consensual criterion are identified, further tests are applied to assess their reliability, validity and additivity (see Guio et al., 2012, 2016; Gordon, 2017). These tests confirm the relevance of each item and the ability of the list as a whole to capture poverty. Deprivation can be measured by setting a threshold and calculating the percentage that falls below it, or by deriving an index score using the ‘counting approach’ (Atkinson 2015)–in aggregate or for specific groups (see Saunders and Naidoo 2017; Patsios et al., 2018).

When combined with the democratic determination and statistical verification of the essential components of a minimally acceptable standard of living, the living standards approach is more direct and has increased credibility compared with the monetary approach. That, at least, is the claim–but how well does it stack up? Concerns have been raised about whether the consensual approach is able to identify a consensus or simply reflects people’s own experience (including their ownership of relevant items or participation in social activities). This issue has been examined by Gutfleisch and Andreβ (2020) who conclude (p. 498) that lists of identified necessities are better described as ‘majoritorian’ rather than ‘consensual’ because; ‘necessity evaluations are affected by what people have or do’ (see also Van Den Bosch, 2001: Chapter 3). Other studies have questioned whether preference adaption causes people to ‘live with their lot’, and to indicate that they do not want items that they do not have, although the evidence on preference adaption is mixed (see Halleröd, 1997; Abe, 2018; Crettaz and Suter, 2013).

Another debate relates to whether items should be weighted when aggregated to form a deprivation measure. These weights could reflect ownership rates (prevalence weighting) or the strength of support for the item being essential (preference weighting) or some alternative scheme.Footnote 9 The idea that those who lack items that most others have or that most people think everyone should have face greater deprivation has intuitive appeal. On an empirical level, Gutfleisch and Andreβ (2020: 497) argue that the items have different discriminatory power and ‘should be differently weighted’. However, the use of weights has been rejected by proponents of the consensual approach, on the grounds that if the items have a high degree of statistically reliability as indicated by the Cronbach alpha statistic, ‘there is little additional information that any differential weights could add’ (Guio et al., 2012: 23; see also Gordon et al., 2012: 1209 and, in the context of child deprivation, Guio et al., 2018: 856). If weights are applied, then deprivation can vary either because more people cannot afford an item or because the weight attached to the item has increased, possibly reflecting a change in attitudes or increased ownership–including among those who are not deprived. Whatever the reason, interpreting change becomes more difficult and in some instances, will be conditional. This issue warrants further examination, although attempts to apply alternative weighting schemes have found that it makes little practical difference to the overall findings (see Halleröd et al., op. cit.).

One clear advantage of the living standards approach is that it negates the need to apply an equivalence scale to adjust for differences in need, since these will be automatically reflected in the ability of the household to achieve a minimal standard of living given the economic resources available to it. If two households have identical resources but different needs, they will be able to achieve different standards of living and will be shown to have different levels of deprivation (as long as the items include some that relate to the needs in question). Another advantage of the consensual approach is that it can be applied to individuals (e.g. to different genders, or to adults and children: see Nandy & Main, 2015) and can thus be used to test the intra-household sharing assumption that is a contested cornerstone of the monetary approach (see Cantillon, 2013; Guio and Van Den Bosch, 2018).

These are significant advantages, although the consensual approach is not free of criticism. The replacement of income by a living standards metric comes at a cost in terms of operational complexity and the interpretation and implications of findings. Whereas the monetary approach indicates how much additional income is needed by those identified as poor (the absolute poverty gap), there is no clear guidance about how much (or what form of) additional support is needed to combat deprivation. Should individual (item-specific) deprivations be addressed directly or are they just an indicator of unacceptable living standards that require a broader approach that addresses the affordability issue? Berthoud and Bryan (2008: 14–15) caution against placing too much emphasis on results for individual items, arguing that:

… it is a tall claim that deprivation indicators provide a more reliable measure than income–however ‘scientific’ the approach to their construction … deprivation indicators make an enormous contribution to our understanding of poverty. But they are just indicators, and it is unhelpful to treat them too literally as direct measures of people’s experience

Although the statistical testing of indicator properties has increased their robustness and relevance, it is still not clear whether they now meet this challenge–particularly since the actual living conditions of those identified as deprived are not observed directly, only inferred from responses about whether they have an item and if not, why. Despite the need for caution, a clear advantage of the deprivation approach is that it reveals what kinds of items those in greatest need are having to forego, and thus provides valuable new information that can help policy makers develop appropriate policy responses.

Finally, there is the issue of thresholds. Most deprivation measures set a threshold to derive a deprivation rate, but this raises similar concerns to those expressed about the arbitrary nature of a poverty line. Townsend tried to address this concern by identifying the income level below which deprivation rises sharply and setting this as his poverty line, but his ‘scientific’ approach was subject to widespread criticism. Despite this, the PSE-UK study has refined the approach by setting a threshold that maximises the difference between ‘poor’ and ‘not poor’ groups while minimising the differences within each group (see Gordon, 2006: 43–44). Weighting avoids the need to set a threshold but introduces a new raft of problems as the earlier discussion indicates. A better approach is to supplement threshold-based incidence rates with an index that summarises the overall level of deprivation. Despite its many attractions the living standards approach, like the monetary approach, has both strengths and weaknesses. What these are and how they balance out requires a robust empirical comparison, as is now presented.

3 Background, Sources and Methods

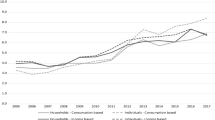

The Australian economy performed strongly throughout the period covered by this analysis. Between 2006 and 2017, the economy grew at an annual average rate of 2.75%, average living standards as measured by household disposable income per capita increased by 17.0% in real terms and the rise in median equivalised household disposable income of over 59% was well in excess of the 34% rise in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), although house prices rose somewhat faster than other prices (see Fig. 1).Footnote 10 The global financial crisis caused unemployment to rise to 5.6 per cent in mid-2009 but that was quickly reversed by fiscal stimulus measures. Inequality was relatively stable throughout the period, the Gini coefficient varying between 0.30 and 0.32–by less than the 3 percentage-point change identified by Atkinson (2015: 52–3) as being ‘sanguine’ for policy purposes.Footnote 11 The period also pre-dates the onset of the covid pandemic and thus avoids its flow-on consequences.

The monetary approach was operationalised following widely accepted practice by setting a range of poverty lines, each set at a fixed percentage of equivalised median disposable household income (EDY).Footnote 12 One problem with this approach is that movements in poverty rates can be driven by changes in median income to produce seemingly perverse results. For example, Jenkins (2016: Fig. 7.7) shows that the decline in relative poverty in the UK following the financial crisis was largely a consequence of the crisis-induced decline in median income. One response to this (adopted by Jenkins, and others including Smeeding, 2016 and Saunders et al., 2016) is to include a measure of anchored poverty based on a poverty line that is adjusted in line with movements in prices but not incomes.Footnote 13 The robustness of the estimates is assessed using poverty lines set at 40%, 50% and 60% of the median, while 2005–06 is set as the base year when deriving the anchored poverty rates. All estimates are person-weighted and poverty rates thus refer to the percentage of individuals living in households with income below the poverty line.

Poverty is estimated both before (BHC) and after (AHC) housing costs are deducted from disposable income, where housing costs include mortgage repayments or rent and other unavoidable housing-related costs such as property taxes or renovation costs.Footnote 14 The AHC measure captures the impact of the traditionally high rate of home ownership in Australia that lowers housing costs for older (often mortgage-free) households, allowing them to avoid poverty despite receiving a government pension that is low by OECD standards (OECD, 2019).Footnote 15

Poverty is estimated using unit record data from the Survey of Income and Housing (SIH) currently conducted every second year by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (see, for example, ABS, 2020). The ABS surveys are conducted throughout the financial year beginning on 1 July and (until recently) collect information on weekly income at the time of the survey and annual income over the previous financial year. The weekly income data are used here.Footnote 16 The ABS has made a series of changes to its income measure in recent surveys but a common definition (that applying in 2005–06) has been applied here to avoid any distortion. Households reporting zero or negative income and those containing any self-employed persons have been removed from the sample.Footnote 17

The living standards approach has been applied using the consensual approach outlined earlier. This produces estimates that are also relative because as noted earlier and by Mack (2018), the items seen as necessary by a majority in the community reflect prevailing perceptions of what is needed to achieve an acceptable standard of living. These items may change over time to reflect changes in item accessibility, ownership, usage and cost, as well as in response to movements in overall living standards However, it is expected that these changes will be less pronounced and occur less frequently than changes in median income.Footnote 18

The deprivation estimates are derived from surveys conducted in 2006, 2010 and 2017.Footnote 19 These surveys replicate the British surveys referred to earlier, appropriately modified to make them compatible with Australian circumstances.Footnote 20 The first two surveys were conducted by mail on a random sample of 6,000 Australians drawn from the electoral roll, both achieving a response rate close to 47 per cent.Footnote 21 Access to the electoral rolls was not available in 2017, so the questionnaire was sent to those who had completed the 2010 survey (and to a smaller follow-up sample of those who completed both the 2006 and 2010 surveys). This resulted in a decline in the response rate (from 47 per cent to around 32 per cent after allowing for incorrect addresses) and probably magnified any unobservable response biases that were present in the two earlier surveys. Details of the recruited and examined samples in each year are presented in Table 1.

The main observable bias in the responding samples in all three years relates to age. In 2010, for example, those aged under-30 account for only 12 per cent of the sample but represent 20 per cent of the population, while the those aged 65 and over account for 23 per cent of the sample but only 18 per cent of the population.Footnote 22 Both misrepresentations are magnified in the 2017 sample. One consequence of using a follow-up approach to recruit the 2017 sample was that all respondents would be at least 25 years of age (7 years above the eligibility voting age of 18 that defined the 2010 respondents), while others would be well into their 70 s and 80 s. In order to avoid placing undue pressure on the latter group and to maximise overall comparability, the sample in all years was restricted to those aged between 25 and 74 years (see the final column of Table 1). This has the added advantage of reducing the age bias in the samples, which was further addressed by re-weighting the data by age (and gender) using national demographic data.

The surveys include a list of items and ask three questions about each of them: Is the item essential for all Australians? Do you have it? and If not, is this because you cannot afford it? The items differ somewhat from year to year, but we focus on the 36 items that are common to all three surveys. The first step in the consensual approach involves identifying items that receive majority support (at least 50% of the weighted total sample) for being essential ‘for all Australians’. Nine items failed to reach this level of support in all three years and were dropped from the analysis. Of the remaining 27 items, support for 24 exceeded the majority support threshold in 2006 and 2010 and 25 items in 2017, 22 of which were the same items in all three years.

The five items that changed status over the period are shown in Table 2. Three items relate to the use of internet-based communication technology and reflect how rapid change in this area has impacted on patterns of community attitudes to their ownership and use. These findings illustrate that the consensual method can identify changes in the availability and use of items and capture changes in community views about which items are essential, even over relatively short periods.

Statistical tests of reliability and validity were conducted on the items that satisfied the consensus criterion.Footnote 23 The reliability tests led to the removal of one item (a television) in 2006 and 2010, while the validity tests suggested the removal of one item (a television) in 2006, no items in 2010 and three items (a substantial daily meal; a washing machine; and a separate bed for each child) in 2017.Footnote 24 This left 18 ‘core’ items that satisfied the consensus, reliability and validity tests in all three years, supplemented by an additional 5 items in 2006 and 2010 bringing the total to 23 in those years, and by a (different) 4 items in 2017 bringing the total for that year to 22. The Cronbach alpha statistics for the final list of items are 0.850 (in 2006), 0.856 (in 2010) and 0.852 (in 2017)–all virtually identical and well above the acceptable minimum of 0.7 recommended for social research studies and high enough to suggest that weighting the items will add little to their overall explanatory power. The items used to estimate deprivation in each year are shown in the Appendix.

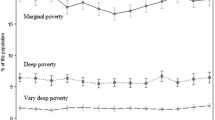

Results are presented for four measures of deprivation: those deprived of no essential items (DEP = 0), those deprived of at least 3 (DEP ≥ 3) or at least 5 (DEP ≥ 5) essential items, and the (unweighted) mean deprivation score (MDS) across all items. As noted earlier, the decision to set deprivation thresholds at 3 or 5 items is arbitrary, although the use of alternative thresholds allows the sensitivity of the estimates to be assessed. Thresholds of at least 3 and at least 5 items also produce deprivation rates in the base year (2006) that are close to the (BHC) poverty rates in that year with poverty lines set at 50% and 60% of median income, respectively. This similarity makes it easier to interpret the results and discern patterns in movements over time since the base year.

It is possible to derive deprivation measures that correspond to the anchored poverty rates by holding the list of essential items unchanged at the base year and estimating deprivation in all three years using this list. However, as the earlier discussion (and Table 2) indicates, there were relatively few changes in the list of identified essentials over the sample period and almost no change in the total number of items. Since it is the number of items that drives the deprivation measures employed here, anchored deprivation rates are not presented but are very similar to those shown (identical in the first two years). Further details are available on request from the authors.

4 Results

4.1 Poverty

Relative and anchored BHC and AHC poverty rates are shown in Table 3. For ease of exposition, the discussion adopts the following terminology: RB40 (and respectively, AB40) refer to the relative (and respectively, anchored) BHC poverty rate at 40% of the median, RB50 (and respectively, AA50) refer to the relative (and respectively, anchored) BHC poverty rate at 50% of the median, and so on–the letters (R and A, and B and A) signifying the poverty measure (relative or anchored, and measured before or after housing costs) and the numbers (40, 50 and 60) where the poverty line is set (the percentage of median income).Footnote 25

Relative BHC poverty declined over the period except at the lowest (40% of the median) poverty line. When the most common (in Australia) RB50 measure is used, the decline was by 2.3 percentage points or 21.5% in proportionate terms, with most of it concentrated in the period after 2010.Footnote 26 Poverty also declined (though by less) using the RB60 measure, with the decline again concentrated in the post-2010 period. However, those in deepest poverty missed out on these implied income gains, with RB40 poverty increasing over the period by an amount that although small in absolute terms, is greater proportionately (31 per cent) than the decline in RB50 poverty. The anchored poverty rates are all below the relative rates reflecting the growth in real incomes over the period (Fig. 1) and the anchor point being the initial year.Footnote 27 AB50 poverty declined by over 5 percentage points, while AB60 poverty declined by more than half (over 10 percentage points)–a substantial change over a relatively short period. However, those in deepest poverty again missed out, with AB40 poverty hardly changing.Footnote 28

The lower panel of Table 3 indicates that the picture changes markedly when housing costs are taken into account.Footnote 29 Both RA40 and RA50 poverty increased, while RA60 poverty hardly changed. Much of the gain in BHC relative poverty resulting from the growth in income over the period was thus offset (or, for the very poorest, compounded) by rising housing costs. All three anchored AHC poverty rates still show a decline, although by less than the BHC measures at the two higher poverty lines. The decline in RB50 poverty of 1.8 percentage points after 2010 shown in the top panel of Table 3 drops to 0.3 percentage points when the anchored poverty measure is used and to 0.4 percentage points when account is taken of housing costs.

This and other results in Table 3 highlight the sensitivity of headcount poverty rate estimates to how poverty is measured–an issue that is particularly relevant in a country like Australia that relies heavily on targeted social security benefits that (by accident more than by design) are set close to 50 per cent of median income in many instances (particularly the age pension). Also of interest, is that the differing fortunes of those below the three poverty lines are consistent with increasing income inequality at the lower end of the distribution. This effect was offset to a degree by changes in housing costs, which impacted more negatively on those with incomes between 50 and 60% of the median than on those with incomes below 40% of the median.

The single most striking feature of Table 3 is the impact of housing costs on poverty, whether measured relatively or on an anchored basis. For example, in 2017–18, taking account of housing costs produces a larger change in the RB50 poverty rate (4.7 percentage points) than the shift from the relative to the anchored measure (3.1 percentage points). This highlights how the debate over whether poverty is relative or ‘absolute’ (measured using an anchored poverty line) has been a distraction, diverting attention away from factors like housing costs that have had a greater impact on driving changes in poverty–at least over the period considered here.

Our analysis leads us to concur with Jenkins (2016: 149) who concludes his analysis of UK poverty trends by noting that: ‘Clearly, the choice of low-income cut-off makes a substantial difference to estimates of both the prevalence of poverty in recent years, and its trend over time’. However, although it is true that how poverty is measured affects the picture at a point in time and how things have changed over time, our results also indicate that some findings are robust across all measures. The most significant of these is that those in deepest poverty have fared worst overall, while for many low-income Australians, the rise in income experienced over the period was barely sufficient (at best) to offset rising housing costs. Finally, it is important to note that the results are being driven more by changes in housing costs than by changes in house prices. Thus, housing costs at for those with median income, increased over the period by 57.9%—far greater than the increase in the difference between the rise in the overall CPI (33.1%) and the increase in the non-Housing CPI (26.4%). Home buyers faced higher prices but following financial market deregulation had access to higher mortgages and it was the interest payments on these that drove housing costs upwards (supplemented by demand-driven increases in rents for the growing number of renters who were unable to afford to buy a house).

4.2 Deprivation

Changes in aggregate deprivation over the period are summarised in Table 4.Footnote 30 As explained earlier, results are presented only for deprivation defined relatively (using the items identified as essential in each year) since the anchored results are very similar given the stability in the number of items identified as essential.Footnote 31 All four deprivation measures indicate a decline in deprivation, spread fairly evenly between the pre-2010 and post-2010 periods. There is a steady and considerable increase in the percentage experiencing no deprivation (DEP = 0), while the DEP ≥ 3 and DEP ≥ 5 measures decline by 5 and 3 percentage points, respectively. The sum-score deprivation index also fell by 23.9% in proportionate terms, almost identical to the proportionate decline in RB50 poverty shown in Table 3. The results suggest little change in inequality when measured using a deprivation metric, with all measures displaying similar improvement.Footnote 32 However, while overall deprivation improved, it remained severe amongst those most disadvantaged in 2017, when around one-in-twelve households were deprived of 5 or more items regarded by a majority of the community as being essential for all. Consistent with the poverty estimates, these households began the period in the worse circumstances and missed out on the subsequent rise in living standards that others experienced.

Is there any evidence from these deprivation results to confirm the important role that rising housing costs played in exacerbating poverty over the period? Not really, although perhaps not surprisingly. In order to explore this issue, we focus on the 5 essential items that are related to housing (see Appendix): a decent and secure home; heating in at least one room of the house; secure locks on doors and windows; a roof and gutters that do not leak; and home contents insurance. Two of these items (adequate heating and home contents insurance) are not included in the definition of housing costs used in the AHC poverty measure and the deprivation rates of the other three housing-related items fell over the period. However, the main rationale for the use of the AHC poverty measure is that housing costs are fixed for most people in the short-run and are hence unavoidable (see Johnson & Webb, 1992). When combined with the logic of the consensual approach, this argument implies that the short-run impact of higher housing costs would most likely be not an increase in housing-related deprivation, but an increase in non-housing deprivation driven by the decline in the housing affordability. The finding that housing deprivation did not increase is thus not inconsistent with rising house prices having undermined the ability of people to meet their basic needs from the resources available to them, although the absence of any evidence that non-housing deprivation increased casts doubt on this explanation.Footnote 33

5 Summary and Conclusions

The results in Tables 3 and 4 indicate that most Australian poverty and deprivation rates declined by modest amounts over the period examined. Deprivation fell across the board—for social activities like going out for a meal with friends, children being able to participate in school trips or having a holiday—and for possessing material items like a mobile phone or washing machine or being able to save for emergencies. Poverty also declined, but the falls were less equally spread with the poorest missing out and with much of the gains for all groups being offset by rising housing costs. Since these rises were concentrated in the latter part of the period examined, it is possible that the flow-on consequences for deprivation had not emerged by the sample end-point in 2017. If there is any truth in this explanation, it suggests that living standards buffers can protect vulnerable groups from income falls that might otherwise send them into (or keep them in) income poverty. These aggregate observations do not detract from the value of having access to the detailed (item-specific) profile of deprivation. This highlights a strength of the deprivation approach, which is its ability to build a picture of how living standards are changing, just as the ability to identify the role of factors like housing costs are a strength of the monetary approach.

Whilst there is clear evidence of progress in tackling social disadvantage in Australia, the degree of improvement—whether measured indirectly using the monetary approach or more directly using the living standards approach, and whether measured relatively to reflect rising incomes and changing community perceptions, or on an anchored basis that reflects only rising prices and holds community perceptions fixed–the measured gains were modest given the strong economic performance achieved over the period. While the real incomes of many of those in poverty increased, they did not keep pace either with the income rises experienced by those close to (and above) the median, or with rising housing costs. Deprivation rates fell but there were still many households unable to afford items that a large proportion of the population regard as essential for all Australians. Our results thus reinforce the conclusion reached recently by Martinez and Perales (2017: 494) that: ‘the ongoing spell of economic growth in Australia will be remembered historically as a lost opportunity to balance the social system’. The Australian economy has performed well but not all boats were lifted by the rising tide.

It was noted at the outset that comparing the results produced by two alternative approaches to identification and measurement of the same phenomena cannot, by itself, indicate which is superior. The aim of this paper was not to make such a choice, but rather to highlight the key features of the monetary (poverty) and living standard (deprivation) approaches in order to better understand their relative contributions to understanding what has happened, and why. The results provide a basis for reflecting on the conceptual and empirical strengths and weaknesses of the two approaches. Despite concerns over its conceptual foundations, the monetary approach provides valuable information not only about the extent of poverty and who is most affected, but also about needed policy responses, not only in relation to raising the incomes of the poor but also designed to ease the financial pressures associated with rising housing costs. Income data is routinely collected by national statistical agencies and made readily available to researchers, who can estimate poverty rates and check their sensitivity to changes in key assumptions. Money also speaks a language that all can understand so analysing the issue using a monetary metric aids the dissemination of findings and can help build a consensus around the need for action.

The deprivation approach is grounded in Townsend’s articulation of poverty as lacking the resources needed to participate fully in one’s society as reflected in prevailing community norms. It views deprivation as an outcome of poverty and has a more direct focus on achievements than the monetary approach, where the focus is on resources. The items used to measure deprivation highlight the dimensions within which any shortfalls exist, and statistical tests ensure that as a group, they capture what it means to be poor. These are formidable strengths that address many of the limitations of the monetary approach, although the living standards approach is not without its limitations. There is a need to examine the impact of how questionnaires are designed, participants recruited, surveys conducted, findings generated, and results interpreted. The living standards approach has undoubted benefits but should be exposed to a similar degree of scrutiny as poverty line studies have experienced for decades before any definitive conclusions can be reached. The results presented here highlight the robustness of the consensual approach and illustrate the many advantages that its more direct focus provides.

Data availability

All data and materials as well as software application or custom code support the published claims and comply with field standards.

Notes

Sen’s theoretical work on capability and functioning (see Sen, 1985) that draws on the concepts of freedom and opportunity in a multidimensional framework represents a third major strand of poverty research, although space prevents us extending the current analysis to include empirical applications of the capability approach. This is an area where further work is warranted.

Examples include the ‘indicator dashboard’ used in Canada or as one component of a multidimensional index, as in New Zealand. Details of the Canadian indicator dashboard is available at: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/topicsd-start/poverty. The New Zealand child poverty measure is discussed in StatsNZ (2019).

The relevance of any line for different households will also depend on the appropriateness of the equivalence scale.

We follow convention and use the ‘modified OECD scale’ (see below) since this is the most widely used scale in poverty research (although it is not used by the OECD itself). The OECD scale assumes that needs only vary between adults and children, and with household size. This means, for example, that the needs of an 18 year-old boy and a 72 year-old woman with a severe disability are assumed to be the same.

The poverty measurement guide recently produced by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) includes a range of deprivation measures and has been endorsed by the Conference of European Statisticians: see https://www.unece.org/stats/ces.html.

The role of choice is not avoided entirely. For example, poorer households may choose not to have children because they cannot afford to, and when asked if they do not have items relating to the needs of children will respond negatively. But if also asked if this is because they cannot afford the items, they should answer negatively and hence will not be identified as deprived.

One possibility that has not been explored would be to weight items by an estimate of their cost, as derived in research on budget standards, that also focuses on minimum standards of living (see Bradshaw et al., 2008).

The ‘Housing’ component of the CPI includes the price of new dwellings purchased by owner-occupiers but excludes mortgage interest repayments and so does not correspond to the definition of housing costs used later. It does, however, include the other components of our measure of housing costs and is used later to anchor the after-housing costs (AHC) poverty line.

The relative stability of income inequality negates the need to apply distribution-sensitive measures (see Datt, 2019) since this would make little difference to the pattern of findings.

This is consistent with a relative conceptualisation of poverty, although this does not automatically imply that its measurement should be adjusted for movements in income. Even if it does, Kangas and Ritakallio (2007) show that different income measures can impact greatly on how estimated poverty rates vary between countries and over time.

The term ‘anchored’ poverty is more appropriate than ‘absolute’ poverty because the choice of anchor point is arbitrary and will affect the estimated levels of poverty (but not the trend).

The distinction between BHC and AHC poverty has been a feature of Australian poverty studies since they began in the 1960s and the use of both measures was recommended by the Commission of Inquiry into Poverty (1975). For consistency, anchored poverty lines are updated in line with movements in the CPI minus the ‘Housing’ component. The same equivalence scale is applied when estimating both BHC and AHC poverty, although a case can be made to vary it given that housing is a key determinant of economies of scale in housing provision and costs. This would further complicate the comparisons and has not been pursued.

Reported incomes in each quarter have been adjusted in line with quarterly within-year CPI movements so that they are all based at the mid-point of each year. This adjustment uses the CPI minus the ‘Housing’ component when estimating AHC poverty.

These exclusions reflect concern over the reliability of the incomes reported by those reporting no or very low incomes and because of the problems of distinguishing between private and business income for the self-employed. The vast majority of the exclusions are self-employed, a group that is often removed when estimating poverty and has been shown to be problematic when estimating deprivation (see Horemans and Marx, 2017).

This implies that deprivation rates will be more stable than poverty rates in both directions, raising less when incomes rise rapidly but declining less when they fall. Deprivation will also lag behind short-run movements in income because items acquired previously will act as a buffer, allowing living standards to be maintained when incomes fall but also taking time to acquire when incomes rise.

Ideally, one would use the same data source to estimate both poverty and deprivation, but this is not possible currently in Australia because no single data source contains the relevant information in the detail required to produce robust estimates of both. This also prevents the estimation of overlaps, which requires a single data source.

This includes using interviews with low-income Australians to help identify items relevant to their needs (see Saunders and Sutherland, 2005).

Details of the first two surveys and the responses generated are provided in Saunders, Naidoo and Griffiths (2008) and Saunders and Wong (2012), respectively. Because voting is compulsory in Australia, the federal electoral roll covers virtually all adult (aged 18 +) Australians and thus provides an excellent sampling frame for national studies.

Part of the under-representation of younger people reflects some reluctance to (or delay in) registering for the electoral roll, although this is not large enough to explain the shortfall.

The survey data were not suitable for conducting the additivity tests described by Guio et al. (2016) and Gordon (2017).

A binary variable was defined according to whether people didn’t have enough to get by on (= 1) or had enough or more than enough (= 0) and binomial logistic regressions were run with each essential item as dependent variable and the ‘income managing’ dummy variable as independent variable. Items failed the validity test if the coefficient on the income managing variable was not statistically significant.

The medians are derived from the distributions that are relevant to each income measure.

Statements about the degree of concentration take account of the greater length of the gap between the final two years than between the initial two years.

The movements in median incomes and consumer prices over the period were such that by 2017–18 the anchored line was 15.3% below the relative line, or just over 42% of median equivalised income.

Part of the explanation for this finding is the decision to index social security payments for the unemployed (Newstart Allowance) to the CPI rather than to a measure of average earnings which applied to most other major social security payments. Another key determinant of low-income growth is the change in the independently-set minimum wage, which increased from $13.37 per hour in July 2006 to $18.29 in July 2017 or by 36.8%, only slightly higher than the increase in the CPI over the period.

The anchored BHC and AHC poverty lines increased over the period by 33.0% and 26.4%, respectively, indicating that housing prices rose more rapidly than non-housing consumer prices.

Deprivation rates for individual items in 2017–18 vary from below 1% (a television; up to date schoolbooks) to almost 20% (up to $2,000 in emergency savings). Details of the item-specific deprivation rates in each year are available on request from the authors.

The values of the four anchored deprivation measures in 2017–18 are: 72.0 (DEP = 0), 13.4 (DEP ≥ 3), 6.9 (DEP ≥ 5) and 0.93 (MDS).

Detailed examination of changes in the deprivation rates of individual items indicates that there is only one item (heating in at least one room of the house) that experienced a rise in deprivation over the period greater than 3 percentage points. This was concentrated in the post-2010 period and reflects substantial increases in gas and electricity prices.

This may be due to the lagged response of deprivation to income movements, discussed earlier, although this seems unlikely given the length of the sample period. Only two items experienced a rise in deprivation greater than 2 percentage points: heating in at least one room in the house, which increased by just under 7 percentage points, and a telephone/landline, which increased by 2 percentage points.

References

Abe, A. K. (2018). Developing deprivation index for children taking into account of adaptive preferences. Child Indicators Research, 12(2), 647–665.

Atkinson, A. B. (1987). On the measurement of poverty. Econometrica, 55(4), 749–764.

Atkinson, A. B. (2015). Inequality. What can be done? Harvard University Press.

Atkinson, A. B., Guio, A.-C., & Marlier, E. (2017). Monitoring social inclusion in Europe. In A. B. Atkinson, A.-M. Guio, & E. Marlier (Eds.), Monitoring social inclusion in Europe (2017th ed., pp. 33–49). Publications Office of the European Union.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2020) Household Income and Income Distribution, Australia, 2017–18, Catalogue No. 6523.0, ABS.

Azpitarte, F. (2014). Was pro-poor economic growth in Australia for the income-poor? And for the multidimensionally-poor? Social Indicators Research, 117(3), 871–905.

Azpitarte, F., & Kalb, G. (2019). ‘Measuring income poverty in Australia: A review of methods and recent trends. In P. Saunders (Ed.), Revisiting henderson: Poverty (pp. 163–187). Melbourne University Press.

Bailey, G., & Bramley, N. (2018). Introduction. In N. Bramley & G. Bailey (Eds.), Poverty and social exclusion in the UK (Vol. 2, pp. 1–24). Policy Press.

Berthoud, R., & Bryan, M. (2008). Deprivation indicators. In R. Berthoud & F. Zantomio (Eds.), Measuring poverty: Seven key issues (pp. 14–15). University of Essex.

Bessell, S. (2015). The individual deprivation measure: Measuring poverty as if gender and inequality matter. Gender & Development, 23(2), 223–240.

Bradbury, S. (2021). Housing Costs and Poverty: Analysing Recent Australian Trends. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, forthcoming., 6, 871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09899-w

Bradshaw, J., Middleton, S., Davis, A., Oldfield, N., Smith, N., Cusworth, L., & Williams, J. (2008). A minimum income standard for Britain: What people think. New York: The Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Cantillon, S. (2013). Measuring differences in living standards within households. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 75(3), 598–610.

Commission of Inquiry into Poverty in Australia (1975) First Main Report. Poverty in Australia, Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Crettaz, E., & Suter, C. (2013). The impact of adaptive preferences on subjective indicators: An analysis of poverty indicators. Social Indicators Research, 114(1), 139–152.

Datt, G. (2019). Distribution-sensitive multidimensional poverty measures. World Bank Economic Review, 33(3), 551–572.

Davidson P., Saunders P., Bradbury M., and Wong M. (2020) Poverty in Australia 2020 Part 1, Overview, ACOSS/UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership Report No. 3, Sydney: ACOSS.

Dermott, E., & Main, G. (Eds.). (2018). Poverty and social exclusion in the UK. Volume1. Policy Press.

Gamble, D. D. (2019). An Australian indigenous advancement agenda. Public Affairs Quarterly, 33(4), 317–352.

Gordon, D. (2006). The concept and measurement of poverty. In C. Pantazis, D. Gordon, & R. Levitas (Eds.), Poverty and social exclusion in Britain (pp. 29–69). Policy Press.

Gordon, D. (2017), PSE-UK 2012 Survey. Producing an ‘Objective’ Poverty Line in Eight Easy Steps,https://www.poverty.ac.uk/editorial/producing-pse-povertyline (accessed on 24/09/2021).

Gordon, D. (2018), ‘Measuring poverty in the UK’, in E. Dermott and G. Main (eds.), Poverty and Social Exclusion in the UK. Volume 1–The Nature and Extent of the Problem, Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 17–39.

Gordon, D., & Pantazis, C. (Eds.). (1997). Breadline Britain in the 1990s. Ashgate.

Gordon, D., et al. (2012). Authors’ response to: Alternatives to principal components analysis to derive asset-based indices to measure socio-economic position in low- and middle-income countries: The case for multiple correspondence analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(4), 1209–1210.

Guio, A.-C., Gordon, D., & Marlier, E. (2012). Measuring material deprivation in the EU: Indicators for the whole population and child-specific indicators. Publications Office of the European Union.

Giuo, A.-C., Marlier, E., Gordon, D., Fahmy, E., Nandy, S., & Pomati, M. (2016). Improving the measurement of material deprivation at the European level. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(3), 219–233.

Guio, A.-C., Gordon, D., Marlier, E., Najera, H., & Pomati, M. (2018). Towards an EU measure of child deprivation. Child Indicators Research., 11, 835–860.

Gutfleisch, T., & Andreβ, H.-J. (2020). Perceptions of society’s necessary standard of living: are perceptions determined by what people have, or do they reflect a social consensus? Social Indicators Research, 149(2), 467–502.

Halleröd, B., Bradshaw, J., & Holmes, H. (1997). Adapting the consensual definition of poverty. In D. Gordon & C. Pantazis (Eds.), Breadline Britain in the 1990s (pp. 213–234). Ashgate.

Hick, R. (2012). The capability approach: Insights for a new poverty focus. Journal of Social Policy, 41(2), 291–308.

Hick, R. (2014). Three perspectives on the mismatch between measures of material poverty. British Journal of Sociology, 66(1), 163–172.

Hick, R. (2016). Material poverty and multiple deprivation in Britain: The distinctiveness of multidimensional assessment. Journal of Public Policy, 36(2), 277–308.

Horemans, J. and Marx, I. (2017), ‘Poverty and material deprivation among self-employed in Europe: an exploration of a relatively unchartered landscape’, Discussion Paper No. 11007, Berlin: IZA Institute of Economics.

Jenkins, S. (2016). The income distribution in the UK: A picture of advantage and disadvantage. In H. Dean & L. Platt (Eds.), Social advantage and disadvantage (pp. 135–160). Oxford University Press.

Johnson, P., & Webb, S. (1992). The treatment of housing costs in official low income statistics. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 155(20), 273–290.

Kangas, O., & Ritakallio, V.-M. (2007). Relative to what? cross national picture of European poverty measured by regional, national and European standards. European Societies, 9(2), 119–145.

Klein, E. (2016). The curious case of using the capability approach in Australian Indigenous policy. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 17(2), 245–259.

Mack, J. (2018). Fifty years of poverty in the UK. In N. Bramley & G. Bailey (Eds.), Poverty and social exclusion in the UK (Vol. 2, pp. 27–56). Policy Press.

Mack, J., & Lansley, S. (1985). Poor Britain. George Allen and Unwin.

Maître, B., Nolan, B. and Whelan, C. T. (2006), ‘Reconfiguring the Measurement of Deprivation and Consistent Poverty in Ireland’, Policy Research Series Number 58, Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute.

Martinez, A., & Perales, F. (2017). The dynamics of multidimensional poverty in contemporary Australia. Social Indicators Research, 130(2), 479–496.

McKay, S. (2004). Poverty or preference: What do “consensual deprivation indicators” really measure? Fiscal Studies, 25(2), 201–223.

Nandy, S. and Main, G. (2015) ‘The consensual approach to child poverty measurement’, CROP Poverty Brief, November, Bergen: CROP, pp. 1–4.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (1996). Resources. Clarendon Press.

OECD (2019), Pensions at a Glance 2019. OECD and G20 Indicators, Paris, OECD Publishing, available at https://doi.org/10.1787/b6d3dcfc-en

Pantazis, C., Gordon, D., & Levitas, R. (Eds.). (2006). Poverty and social exclusion in Britain. Policy Press.

Patsios, D., Pomati, M., & Hillyard, P. (2018). Living standards in the UK. In N. Bramley & G. Bailey (Eds.), Poverty and social exclusion in the UK (Vol. 2, pp. 57–89). Policy Press.

Perry, B. (2002). The mismatch between income measures and direct outcome measures of poverty. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 19, 101–126.

Piachaud, D. (1981), ‘Peter Townsend and the Holy Grail’, New Society, September: 419–21.

Rodgers, J. R., & Rodgers, J. L. (2009). ‘Contributions of longitudinal data to poverty measurement in Australia’,. Economic Record, 85, S35–S47.

Rodgers, J. R., Siminski, P., & Bishop, J. (2009). Changes in poverty rates during the Howard era. Australian Economic Review, 42(3), 300–320.

Saunders, P. (2017). Housing costs, poverty and inequality in Australia. Housing Studies, 32(6), 742–757.

Saunders, P., & Sutherland, K. (2005). Experiencing poverty: The voices of low-income Australians. Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales.

Saunders, P., & Naidoo, Y. (2019a). The low overlap between income poverty and material deprivation: Sensitivity evidence for Australia. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 28(2), 187–206.

Saunders, P., Naidoo, Y., & Griffiths, M. (2008). Towards new indicators of disadvantage: Deprivation and social exclusion in Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 43(2), 175–194.

Saunders, P., & Naidoo, Y. (2018). Mapping the Australian poverty profile: A multidimensional deprivation approach. Australian Economic Review, 51(3), 336–350.

Saunders, P., & Naidoo, Y. (2019b). Poverty as relative deprivation: application, analysis and implications for social security. In P. Saunders (Ed.), Revisiting henderson: poverty (pp. 189–213). Melbourne University Press.

Saunders, P., & Wong, M. (2012). Promoting inclusion and combating deprivation: Recent changes in social disadvantage in Australia. Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales.

Saunders, P., Wong, M., & Bradbury, B. (2016). Poverty in Australia since the financial crisis: The role of housing costs, income growth and unemployment. The Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 24(2), 97–112.

Scutella, R., Wilkins, R., & Kostenko, W. (2009). Estimates of Poverty and Social Exclusion in Australia: A multi-dimensional approach. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic & Social Research.

Sen, A. K. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. North-Holland.

Smeeding, T. M. (2016). Poverty measurement. In D. Brady & L. M. Burton (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the social science of poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sollis, K. (2019), Measuring Child Deprivation and Opportunity in Australia: Applying the NEST Framework to Develop a Measure of Deprivation and opportunity for Children Using the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY).

StatsNZ (2010), Measuring Child Poverty: Material Hardship. Retrieved from: www.stats.gov.nz

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. Penguin Books.

Townsend, P. (1987). Deprivation. Journal of Social Policy, 16(2), 125–146.

Van Den Bosch, K. (2001). Identifying the poor. Using subjective and consensual measures. Ashgate.

Wilkins, R. (2017), The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 15. The 12th Annual Statistical Report of the HILDA Survey, Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic & Social Research.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the detailed and helpful comments provided by two anonymous referees and the technical advice provided by Bruce Bradbury but remain responsible for any remaining errors. Financial support was provided by the Australian Research Council through project grants LP0560797, LP100100562 and DP160102047

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Funding was provided by the Australian Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix: Items Included in the Deprivation Analysis

Included in all 3 years

A decent and secure home.

Warm clothes and bedding, if it's cold.

Heating in at least one room of the house.

Furniture in reasonable condition.

Comprehensive motor vehicle insurance.

Up to $500 in savings for an emergency.

Up to date schoolbooks and new school clothes for school-age children.

Children can participate in school activities and outings.

A hobby or leisure activity for children.

Secure locks on doors and windows.

A roof and gutters that do not leak.

Home contents insurance.

Medical treatment if needed.

Able to buy medicines prescribed by a doctor.

Dental treatment if needed.

A yearly dental check-up for children.

Regular social contact with other people.

Presents for family or friends at least once a year.

Items included in 2006 and 2010 only

A substantial meal at least once a day (V17).

A telephone/landline (C17).

A washing machine (V17).

A separate bed for each child (V17).

A week’s holiday away from home each year (C17).

Items included in 2017 only

Mobile phone (C06 & C10).

A television (R06, R10 & V06).

Access to the internet at home (C06 & C10).

Up to $2000 in savings for an emergency (C06 & C10).

Note: Brackets indicate that the item failed the consensus (C), reliability (R) or validity (V) tests in 2006 (06), 2010 (10) or 2017 (17).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saunders, P., Naidoo, Y. & Wong, M. Comparing the Monetary and Living Standards Approaches to Poverty Using the Australian Experience. Soc Indic Res 162, 1365–1385 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02888-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02888-8