Abstract

Providing unpaid informal care to someone who is ill or disabled is a common experience in later life. While a supportive and potentially rewarding role, informal care can become a time and emotionally demanding activity, which may hinder older adults’ quality of life. In a context of rising demand for informal carers, we investigated how caregiving states and transitions are linked to overall levels and changes in quality of life, and how the relationship varies according to care intensity and burden. We used fixed effects and change analyses to examine six-wave panel data (2008–2018) from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH, n = 5076; ages 50–74). The CASP-19 scale is used to assess both positive and negative aspects of older adults’ quality of life. Caregiving was related with lower levels of quality of life in a graded manner, with those providing more weekly hours and reporting greater burden experiencing larger declines. Two-year transitions corresponding to starting, ceasing and continuing care provision were associated with lower levels of quality of life, compared to continuously not caregiving. Starting and ceasing caregiving were associated with negative and positive changes in quality of life score, respectively, suggesting that cessation of care leads to improvements despite persistent lower overall levels of quality of life. Measures to reduce care burden or time spent providing informal care are likely to improve the quality of life of older people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Improved health and survival into later life have enabled a new phase of life to be observed. Described as the Third Age, it is a period of freedom from labour market activities with possibilities for “personal achievement and fulfilment” (Laslett 1989, p. 4). Leaving the labour market does not necessarily enable people to gain personal control over their time and activities, however, since people may be providing unpaid informal care. Informal caregiving is the provision of care for someone who is ill or disabled by somebody from the cared-for person’s intimate environment who is not remunerated or trained (National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP Public Policy Institute 2015). These contributions, reported as substantial in economic evaluations, maintain the sustainability of the wider social care system (Hollander et al. 2009). Informal carers are a pivotal part of the long-term care system, shouldering the burden of care where formal care services are unavailable and aiding care receivers in accessing formal care services (Chappell and Blandford 1991).

Retrenchment of formal care provision has contributed to increased rates of informal caregiving over recent decades, including in certain countries traditionally viewed as having a universal eldercare model. In Sweden, reductions of residential care beds have not been adequately compensated for by increases in homecare services, leading to substantial increases in family provision, or re-familialization, of care (Ulmanen and Szebehely 2015). Recent figures from Sweden show that around 14% of the adult population is now providing informal care at least every week (Socialstyrelsen 2014, p. 16). Ageing populations are causing people over pension age to be a particularly fast growing group of caregivers, as care obligations, in particular towards ageing parents and spouses, are increasing (Carers UK and Age UK 2015; Pickard 2015). While this form of unpaid work is most prevalent in mid to later life (circa 45–65 years), the time spent caregiving increases with age, with people aged 65–80 providing the most time in Sweden, commonly as spousal caregivers (Dahlberg et al. 2007; Socialstyrelsen 2014; Verbakel et al. 2017).

1.1 Potential Impact of Caregiving upon Quality of Life

While where possible in this brief review of the evidence we focus on studies of older adults, we include wider evidence from studies of the general population which likely include substantial numbers of older carers. From the perspective of the third age, some aspects of providing informal care may be positive, such as offering a self-esteem enhancing role (Jacobi et al. 2003) and productive activity (Matz-Costa et al. 2014). Informal care may thereby provide an additional rewarding role (role enhancement) (Rozario et al. 2004), which might improve carer quality of life (Ang and Jiaqing 2012; Brown and Brown 2014). Specifically, prior research has linked providing extra-residential care for a parent to higher sense of mastery (Hansen et al. 2013) and, in women, with heightened reported purpose in life (Marks et al. 2002).

However, caregiving has been linked to a host of detrimental outcomes and circumstances. While noting possibilities for potential benefits of caregiving, the caregiver stress model, developed by Pearlin et al. (1990), emphasizes the major sources of stresses that informal caregiving exposes caregivers to. There is evidence that informal care provision leads to carer psychological distress, lower wellbeing and poorer quality of life. Meta-analyses of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have reported positive associations between subjective care burden and depressive symptoms (del-Pino-Casado et al. 2019) and between caring for frail, older adults and worse wellbeing, depression, self-efficacy and physical health (Pinquart and Sörensen 2003). However, a large portion of the studies included in these reviews were based on non-probabilistic samples or focused exclusively on the particularly vulnerable group of dementia carers.

Turning to population-based studies examining wellbeing and quality of life, the picture is mixed, including negative impacts of caregiving (Broek and Grundy 2018; Chen et al. 2019; Hirst 2005; van den Berg et al. 2014; Verbakel et al. 2017, 2018), no significant effects (McMunn et al. 2009; Wahrendorf and Siegrist 2010), negative effects only for specific subgroups (Hansen et al. 2013; Lacey et al. 2019; Zaninotto et al. 2013), or even positive effects (Hansen et al. 2013; McMunn et al. 2009). One reason for such heterogeneity might be differences in study design, in particular the degree to which selection into caregiving has been controlled for. In cross-sectional studies it is difficult to discern whether effects are due to caregiving or have resulted from selection into the caregiving role of people who were already distinctive in terms of their quality of life. For this reason, in the current study, we take a longitudinal approach to analysing community-based data in order to control better for selection into caregiving and obtain more robust evidence regarding the impact of caregiving upon quality of life of the carer.

1.2 Intensity of Caregiving and Carer Burden

Another important reason for these disparate conclusions about the impact of caregiving on carer quality of life is diversity in caregivers’ experiences. Aspects of the care situation may be important in determining whether role enhancement or caregiver stress is dominant. One important aspect is whether providing care is experienced as burdensome by the carer. It has been suggested that the negative effect of informal caregiving on health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms may be limited to carers who report that it is an emotional or mental strain to provide this care (Roth et al. 2009). Another possible source of discordance among studies is few studies have distinguished levels of intensity of care. Carers providing more intensive care tend to have lower life satisfaction and health than non-carers; low-intensity carers are often indistinguishable from non-carers (Borg and Hallberg 2006; Chen et al. 2019; Ross et al. 2008, p. 44; van den Berg et al. 2014).

In the current study, we distinguish different sorts of caregiving, specifically examining care provided at differing intensities in terms of weekly hours and whether the carer experiences caregiving as burdensome. It is possible that providing care in a non-intensive way (e.g., no more than a few hours per week) may enhance quality of life by encouraging social connection, but that more intensive caregiving may generate difficulties. Similarly, if providing care is not burdensome, quality of life might be enhanced. Existing research into quality of life of informal carers may lump together very dissimilar carers, thereby generating inconsistent findings. By distinguishing levels of intensity of caregiving and carer burden, we can examine longitudinal associations between provision of informal care and quality of life in a more nuanced way, and explore whether providing informal care might have both positive and negative impacts upon quality of life.

1.3 Transitions into and out of Caregiving

Over the adult lifecourse, providing informal care to an ill or disabled adult is a relatively commonplace role, involving instances in which individuals are taking up, continuing and ceasing engagement in informal care. Yet, there is limited evidence regarding the impact of transitions into and out of informal care upon carer quality of life and wellbeing. Transitions into caregiving have been associated with declines in wellbeing and quality of life (Hirst 2005; Marks et al. 2002; Pinquart and Sörensen 2003; Rafnsson et al. 2017). Transitions out of caregiving have been associated with poorer wellbeing (Dolan et al. 2008; Hirst 2005), perhaps because this corresponds to the life event of a close family member entering an institution or passing away, but other studies found no change in quality of life (Rafnsson et al. 2017; Yiengprugsawan et al. 2016). A key question raised by Rafnsson et al. (2017) is whether people who stop providing informal care experience full recovery to pre-caregiving level or longer-lasting effects can be observed. In addition, little is known about which aspects of the care situation might be generating such changes in quality of life: declines may be more marked if people begin high intensity care or burdensome care, and there may also be gender differences, e.g., women providing ≥ 20 h of care weekly were particularly vulnerable to mental health decline (Hirst 2005). In the current study, we use panel data in order to investigate the impact upon caregivers of transitions into and out of caregiving and, in addition, whether any negative impacts of caregiving might be ameliorated (e.g., via adaptation) or exacerbated (e.g., via wear-and-tear) over time.

The aim of this study is to examine longitudinal associations between caregiving, including transitions into and out of caregiving, and quality of life using a large community-based sample. We address the following research questions:

-

1.

How is providing informal care associated with concurrent quality of life?

-

2.

Does the relationship between informal care and quality of life differ for carers who provide a high number of hours of care or who report that caregiving is burdensome?

-

3.

How does entering or exiting providing informal care impact quality of life for carers?

This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, we exploit the longitudinal nature of the data to address potential issues of selection, by using fixed effects modelling in which stable characteristics are accounted for. Analyses are additionally adjusted for potential time-varying confounders such as poor health or pre-existing depression. Furthermore, we also analyse how caregiving transitions are linked to both the level of and changes in quality of life, providing insight into the dynamics and the temporality of the relationship. Second, we explore the relationship in terms of quality of life differences between carers and non-carers, as well as in terms of the intensity (weekly hours) and the burden (subjective care-related burden) of caregiving. In this way, our analyses acknowledge the diversity of caregivers’ experiences. Third, we use the CASP-19 scale that is a measure sensitive to both positive and negative aspects of quality of life. The CASP-19 (control, autonomy, self-realization and pleasure) scale is specifically designed to measure quality of life among older adults, by incorporating eudaemonic (whether activities are meaningful) and hedonic (whether activities are pleasurable) aspects of wellbeing. This is particularly important given that we evaluate caregiving according to burden and weekly hours. Through the CASP-19 measure, as well as capturing any expected negative effect of care for caregivers involved in more demanding roles, we also assess any potential positive impact for those carers who provide fewer hours and do not report burden. Lastly, the study is carried out in a sample of people who perform paid work only at low intensity or not at all, which means that role conflict between caregiving and paid work is unlikely to be an important factor in any observed relationships.

2 Data and Method

2.1 Data

We used data from the 2008 to 2018 waves of the biennial Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH, total N = 40,877) (Magnusson Hanson et al. 2018). SLOSH follows-up respondents from the Swedish Work Environment Survey (SWES) 2003–2011 and is consequently drawn from the Swedish working population aged 16–64 years. Out of 40,877 individuals included in SWES 2003–2011, 70% responded to at least one of the SLOSH waves and response rates to each SLOSH wave range from 51 to 65% (Magnusson Hanson et al. 2018). Data collected by postal questionnaires are linked to administrative registers. Participants are asked to complete either an “in-work questionnaire”, if they are in paid work for at least 30% of full time, or a “non-worker questionnaire” if they are in paid work less than 30% or are outside the labour force, e.g. unemployed or retired people. Respondents have provided informed consent and Stockholm’s Regional Research Ethics Board has approved both SLOSH and the present study.

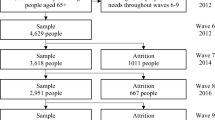

Since the CASP-19 quality of life scale was only included in the non-worker questionnaires, information solely from these questionnaires was used. The study sample was restricted to participants in early old age, aged 50–74, and contained only participants who provided data for at least two waves. These restrictions led to a sample of 5076 individuals (14,912 observations) who provided an average of 2.9 observations each (range 2–6) for the concurrent analyses. Participants who had not provided at least two consecutive waves of data were excluded from the change analyses, given that changes in caregiving and quality of life could not be calculated for them. This led to a sample of 4713 individuals (9163 observations) and up to a maximum of five transitions for the change analyses.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Providing Informal Care

Two questions asked respondents whether they are caring for or helping an older person and whether they are caring for or helping another person (child or adult) who is sick or disabled. For both types of care, respondents were asked to write in the average number of hours weekly spent caregiving and whether they experienced it as a burden with the responses: often, sometimes and never. From these original variables, we created three caregiving measures. The first variable is a binary measure distinguishing people providing care for an old, ill or disabled person from those who were not. For the second variable, intensity of care, we added together the hours of care reported to create a measure of hours of caregiving weekly with six categories: zero hours of care, including non-carers; 1–4 h; 5–9 h; 10–19 h; 20–49 h; and ≥ 50 h. For the third variable, care burden, carers were assigned to one of four categories based on the highest care burden they described: non-carers; carers never experiencing burden; carers sometimes experiencing burden; and carers often experiencing burden.

For each of the three caregiving measures, change variables describing caregiving activity over two consecutive points were created for the five periods: 2008–2010, 2010–2012, 2012–2014, 2014–2016 and 2016–2018. In the case of the binary caregiving measure, these categories were: providing care at neither wave, providing care only at the later wave, providing care only at the earlier wave, providing care at both waves. As an example, a participant providing care in 2012 only would be providing care at neither wave in the period 2008–2010, providing care at the later wave in the period 2010–2012 and providing care only at the earlier wave in the period 2012–2014. Variables were created in the same way for caregiving intensity (dichotomized at 0–9 h; and ≥ 10 h weekly) and burden (non-carers/carers never experiencing burden; and caregiving was sometimes/often burdensome).

2.2.2 Quality of Life

Quality of life was measured using the CASP-19 scale, a multidimensional measure of quality of life. The scale resides within an established tradition of measuring subjective well-being in terms of evaluating the experience of the individual, including positive elements rather than the absence of negative factors and assessing a broad range of life domains (Wiggins et al. 2008). CASP-19 incorporates hedonic elements, like scales measuring happiness, and eudaemonic elements, like scales measuring psychological well-being or life satisfaction. It was designed for use in early old age and draws on sociological ideas of the third age which centre older people’s capacities to lead rich and fulfilling lives (Higgs et al. 2003). The 19 items each draw from one of four domains of control, autonomy, self-realization and pleasure (Hyde et al. 2003). From this perspective, quality of life is shaped by individuals’ freedom to act and to be free of the unwanted interference of others, as well as the freedom to choose to carry out activities that have meaning for them and make them happy (Higgs et al. 2003; Hyde et al. 2003).

The CASP-19 scale ranges from 0–57, where higher scores indicate better quality of life. Each item is scored on a four-point adverbial scale from 0–3 (often, sometimes, rarely, never); six items are reverse coded. Where up to four items were missing, the average of the remaining items for that individual was used to recalculate the score out of 57 points. Cronbach’s α values for each survey wave ranged from 0.89 to 0.91.

2.2.3 Covariates

Covariates which potentially confound the relationship of interest were selected according to existing knowledge of the predictors of quality of life and provision of informal care, and theoretical considerations as to whether covariates could instead be considered mediators lying on the causal pathway. Sociodemographic characteristics which might affect both quality of life and propensity to provide care were controlled for. Specifically, information on age, gender, marital status, education and income quintiles were drawn from the Statistics Sweden’s Longitudinal Individual Data Base (LISA) administrative register, through data linkage based on individuals’ personal identification numbers. Age was included as a linear measure mean-centred at 67.5 years. Highest attained education level was grouped into four categories: compulsory schooling; up to two or four years of upper secondary/vocational training; university or equivalent shorter than three years; and at least three years of university or equivalent. Income quintiles were calculated for each wave (1 = lowest quintile; 5 = highest).

Models were adjusted for health since being in poor health is associated with poorer quality of life and may also affect the likelihood of providing informal care in two directions: by health problems preventing individuals from providing informal care and by increasing the chance that people are in close relationships with others who are also in poor health, thereby increasing the likelihood of providing care. An indicator for presence of chronic illness in the previous two years that affects activities was constructed from a question asking respondents whether they suffered from any of a list of nine illnesses (hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, rheumatism, musculoskeletal disease, psychiatric disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other diseases/complaints). The resulting binary indicator grouped together those who reported that at least one of the ailments affected their life a little or a lot; as opposed to having none of the illnesses, or none of the illnesses affecting their life. General self-rated health was measured with a single-item five-point Likert scale asking “How would you rate your general state of health”, with the response options: very good, good, neither good nor bad, quite poor, or very poor. It is a measure of general physical and mental health that predicts mortality (2007).

Depressive symptomatology was measured using a brief six-item version of the Symptom Checklist Core Depression Scale (SCL-CD6) which provides a summed score ranging from 0–24 (Magnusson Hanson et al. 2014). Items assess the extent (0 = not at all; 4 = very much) of how much various depressive symptoms (lethargy, feeling blue, self-blame, over-worrying, anhedonia, and feeling that everything is an effort) trouble respondents. While depressive symptoms may confound the relationship between providing care and quality of life, especially due to the risk of response bias in relation to assessments of whether care is burdensome, depressive symptoms are likely to also be an important mediator of the effects of caregiving on quality of life. In addition, several items of the SCL-CD6 and CASP-19, concerning lethargy, feeling blue and anhedonia, resemble each other; a known problem in analyses using CASP-19 alongside depression scales (Platts 2014, p. 293). Controlling estimates for depressive symptoms may lead to overadjustment bias or to unnecessary adjustment, therefore we include depressive symptomatology score as an additional covariate in sensitivity analyses.

2.3 Analyses

Two sets of analyses were carried out in order to examine the longitudinal relationships between caregiving and quality of life, with the first focusing on how caregiving influences concurrent levels of quality of life, and the second on how caregiving wave on wave transitions are linked to levels of and instantaneous changes in CASP-19. First, we utilised fixed effects (FE) models to evaluate the relationship between concurrently measured caregiving and quality of life. FE estimation controls for unobserved time-invariant characteristics that vary across individuals by using only within-person variability (Allison 2009). This approach addresses the issue of selection into caregiving due to unobserved time-invariant characteristics, e.g., if unmeasured personality traits and attitudes are associated with taking up caregiving and reporting of quality of life, thereby confounding the relationship. We investigated how providing care is associated with quality of life in three sets of analyses: providing any care, hours weekly providing care, and care burden. Time-constant variables (gender and education) were automatically omitted from the fixed effects models.

In the second set of analyses, change analyses, we examined how changes in caregiving over consecutive waves, i.e., transitions from wave t0 to t1, are associated with: (1) CASP-19 quality of life at wave t1 and (2) CASP-19 change scores calculated as the difference score between consecutive waves (t1 – t0). Random intercept models with maximum likelihood estimation were used in the former case, for modelling CASP-19 measured at wave t1 as the outcome. In the latter case, also known as first-differenced (FD) estimation (Andreß et al. 2013), we used ordinary least square regression with robust standard errors to account for clustering within individuals’ repeated observations. The FD approach allows instantaneous changes in the outcome (CASP-19) to be modelled. These change analyses show how starting, continuing, or ceasing provision of informal care are related to overall levels of and changes in quality of life, in relation to the reference group of not providing care for two consecutive waves. Covariates were taken from the second of the two waves (t1). Three definitions of caregiving were used to define care changes from one wave to the next: providing any care; providing ≥ 10 h weekly; providing care that was sometimes or often burdensome.

Statistical analysis was carried out in Stata 15.1 (StataCorp 2017). Regression coefficients from the linear panel models along with 95% confidence intervals are presented for all analyses. We present unadjusted models for the relationship between caregiving and quality of life (model 1), as well as adjusting for sociodemographic factors, life being affected by chronic conditions and self-rated health (model 2). Lastly, we control for depressive symptoms as a sensitivity analysis (model 3).

The CASP-19 measure is intended to be distinct of individual or contextual factors that influence quality of life, such as health or material circumstances. It does, however, include the item “family responsibilities prevent me from doing what I want to do”, which risks conflating subjective quality of life with objective circumstances (Vanhoutte 2012). Therefore, in sensitivity analyses, we excluded this item reran the analyses with the remaining 18 CASP items. Since previous research has indicated that the effect of caregiving may differ by gender (Lacey et al. 2019), in additional sensitivity analyses, we examined interactions between the three caregiving variables and gender.

3 Results

Cross-sectional point prevalences of caregiving by sociodemographic and health characteristics are presented in Table 1 using information from the baseline survey year for each individual included in the study sample. Asked if they were providing informal care, most did not report providing informal care, while 19% did. In terms of hours of care provided at baseline, most people provided low intensity care: 8% reported providing 1–4 h of care weekly, 5% 5–9 h, 4% 10–19 h and 2% ≥ 20 h. At baseline, the majority of people providing informal care did not describe it as burdensome (11% of the sample), with 8% describing it as sometimes burdensome and 1% as often burdensome. Spending more hours providing care was correlated with care burden: of those providing care for 1–4 h weekly, 32% reported that caregiving was sometimes or often burdensome; at ≥ 50 h weekly, 79% reported that it was sometimes or often burdensome. Carers were more likely to be female, slightly younger, more educated, married, and to report life-affecting chronic illness, poorer health, more depressive symptoms and lower CASP-19 quality of life. CASP-19 scores were lower than for non-carers (44.9 points) if participants provided care for 10–19 h weekly (42.5 points) or if participants provided care that was sometimes burdensome (41.8 points). This last value is at the same level as the mean value in the sample for people whose lives are affected by chronic disease.

While providing informal care may seem a relatively rare state considering point prevalences at baseline in Table 1, there was considerable variation over time, with a substantially higher proportion of individuals providing care at some point during follow-up (period prevalences). Out of the full sample, during one time point at least, 33% provided informal care, 4% provided ≥ 20 h of care weekly and 17% provided care which was reported to be sometimes or often burdensome. Focussing on the incidences of changes in caregiving status in the change analyses sample, i.e., restricting the longitudinal sample to pairs of observations across consecutive waves, we observed that among the 9163 observed transitions that occurred across 4713 individuals at any time during the 2008–2018 period, there were 718 instances where a respondent reported caregiving at a wave following one where they were not, likely indicating a caregiving start; 736 instances where a respondent reported not providing care following a wave where they were caregiving, likely indicating cessation of caregiving; and 961 instances where individuals reported caregiving across a pair of consecutive waves. Considering care transitions only when at least 10 h of care per week are provided, we observed 282 care starts, 282 care cessations and 235 care continuations. Focusing only on care only when it is perceived to be sometimes or often burdensome, we observed 395 starts, 397 cessations and 367 continuations.

Findings from multivariate FE effects models of the concurrent relationship between caregiving and quality of life are presented in Table 2 and the Fig. 1 (plate 1). Compared to non-carers, providing informal care was associated with lower quality of life by − 0.62 CASP points in the adjusted model. Models evaluating hours of weekly care suggest a graded relationship, in which more hours of care provided are associated with lower quality of life. The effects are statistically significant at p < 0.001 if at least 10 h of care weekly were provided (Table 2 and Fig. 1: plate 1), a finding which held after covariate adjustment. A graded relationship with care burden was similarly observed, with significant differences for care which was reported to be sometimes or often burdensome; differences which remained statistically significant, albeit slightly weaker, in sensitivity analyses adjusting for depressive symptoms (Table 2). The relationship with caregiving without burden was considerably weaker and non-significant.

Note: The graphs are adjusted for age, gender, education level, marital status, income quintiles, chronic illness that affects activities, and self-rated health. Plate 1: Fixed effect estimation, plate 2: Random effects estimation, plate 3: First differenced ordinary least squares

Coefficient plots of CASP-19 quality of life and change in quality of life following covariate adjustment, Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health 2008–2018.

The multivariate analyses shown in Table 3 (n = 4713) evaluate the associations of caregiving changes over two-wave periods on: (1) CASP-19 at the later of the two waves and (2) on CASP-19 changes over the same period. In the first set of analyses (Table 3: left-hand side, Fig. 1: plate 2), compared to not providing care at either of the consecutive waves, providing care at one or both waves in a two-wave period was associated with lower quality of life in unadjusted analyses (model 1). The effect for caregiving at the earlier of the two consecutive waves was attenuated and no longer significant after covariate adjustment (model 2). Conversely, compared to not caregiving at either wave, quality of life at the second wave was − 0.75 points lower when caregiving at only the subsequent wave, and − 1.23 points lower when providing care at both waves.

Effect sizes were larger in analyses which examined changes in providing informal care in relation to providing care for ≥ 10 h weekly and in relation to participants who declared that caregiving was sometimes or often burdensome (Table 3 and Fig. 1: plate 2). These effects were all robust to full statistical adjustment for sociodemographic and health covariates (model 2). An additional Wald test showed that burdensome caregiving at both waves was associated with a significantly lower quality of life than only providing care at the second wave (χ2: 9.58, p = 0.002). With the exception of ceasing caregiving for ≥ 10 h weekly, associations observed in the models 2 were attenuated but remained significant after inclusion of depressive symptoms in sensitivity analyses.

The second set of change analyses (Table 3: right-hand side, Fig. 1: plate 3) display associations between changes in caregiving over consecutive waves upon changes in CASP-19 quality of life over the same period. We describe findings after adjustment for covariates in model 2; unadjusted findings were similar. Providing care only at the following or at both waves in a two-wave period did not yield any significant changes in CASP-19 scores compared to not providing care at either wave. However, providing care at the earlier but not at the later wave was linked to a 0.70 point increase in quality of life score. When considering ≥ 10 h of care weekly for caregiving changes, providing such care at only the later wave was associated with − 1.26 point reduction in CASP-19 scores. The opposite case, where such care was provided at the earlier but not the later wave in a two-wave period was associated with 1.22 point in CASP-19 scores. Concerning care that was sometimes or often burdensome, providing such care at the later wave was associated with − 0.70 point reduction in CASP-19 and providing such care at the earlier but not the later wave was associated with a 1.32 point increase in CASP-19. Apart from the reduction in CASP-19 associated with beginning to report that care was burdensome, these associations remained significant after inclusion of depressive symptoms. In all the models considering care that either involves ≥ 10 h weekly or is perceived as burdensome, providing such care at both waves yielded estimates of CASP-19 change that were not significantly different to not providing care in either wave.

Sensitivity analyses using the modified CASP-18 scale, in which the item relating to family responsibilities was excluded, showed weaker associations, which were not qualitatively different from the one produced for the full scale (results in appendix). In sensitivity analyses including interaction terms between the caregiving variables and gender, the overall picture was one in which gender did not alter the relationship between caregiving and quality of life beyond what might be expected through chance (results available upon request).

4 Discussion

In this large community-based sample, providing informal care was associated with lower carer quality of life. Graded relationships were observed with care intensity and care burden, with lowest quality of life scores reported by participants who were providing 50 or more hours of care weekly and by participants who reported that caregiving was often burdensome. These associations, estimated using FE modelling in which each person is their own control, were also robust to inclusion of time-varying socio-demographic and health covariates which might confound the relationship between providing care and quality of life. The findings provide additional support for prior research which found negative impacts on carer wellbeing and quality of life of caregiving (Chen et al. 2019; Pinquart and Sörensen 2003; van den Berg et al. 2014). That in none of the analyses, even with this large sample, were we able to show that providing informal care was positive for carer quality of life counters recent claims about the need to reappraise current evidence in favour of the potential benefits of caregiving (Brown and Brown 2014; Roth et al. 2015). This is notable because we used a quality of life measure, CASP-19, that would be sensitive to any life-enhancing aspects of caregiving. In addition, the findings refer to carers who are not in paid work or are in low-intensity paid work (less than 30% of full-time), which means that they were unlikely to experience conflict between paid work and caregiving. Our results suggest that providing a low number of hours of care has no significant negative effect, which might be different among full-time workers. For those, even less than 10 additional hours of unpaid work may have negative effects.

The estimated point prevalence of informal caregiving is similar to the one reported by Swedish authorities that approximately one fifth of the adult Swedish population regularly provides informal care (Socialstyrelsen 2014). However, the period prevalence (i.e., those providing care during any of the follow-up measurements) estimated in our sample is considerably higher: about one-third of the participants provided informal care at least once and 18% provided care that was sometimes or often burdensome at least once. This corroborates what has been reported in previous studies regarding the dynamic nature of carer populations characterised by high turnover rates, with several starts and cessations of care over time (Hirst 2002; Howe et al. 1997; Seltzer and Li 2000). Informal care may seem a less common experience in cross-sectional snapshots, which tend to underrepresent short spells in caregiving, than in estimates accounting for dynamics of care, since providing care at some point during the lifecourse is a common experience (Hirst 2002; Howe et al. 1997). The implications are that the contribution and needs of a large proportion of carers may go unrecognised by administrative services that provide support to informal carers and care receivers (Hirst 2002).

Substantial diversity in the experience of caregiving could be observed. Over half of the informal carers in this community sample provided fewer than 10 h of care per week or did not report that caregiving was a burden; declines in quality of life for these large groups were not observable. In contrast, people who provided care for ≥ 50 h weekly or who reported that care was often burdensome reported poorest quality of life. While differences in quality of life were visible where the exposure variable was any caregiving provided, they were small, and could easily be missed in studies using small samples. Therefore, future studies should avoid lumping caregivers into a unique group, but instead distinguish carers according to intensity of care and perceived burden, when examining how caregiving influences health-related outcomes. Recognising the diversity in care experiences is necessary to identify those carers who have a heightened risk of experiencing worse quality of life.

These findings are in line with the caregiver stress model, which depicts how provision of informal care exposes carers to a range of stressors, the nature of which depends on characteristics of the carer, the broader context and the specificities of the care situation, e.g., the needs of the cared-for person and the type and magnitude of care demands (Pearlin et al. 1990). As well as affecting quality of life directly, these primary stressors, or demands of caregiving, may in turn lead to other problems, such as no longer having time and energy for preferred activities, which may in turn also affect quality of life. Future longitudinal and lifecourse research might explore the mechanisms by which provision of informal care affects quality of life.

There were associations between entering and exiting caregiving and carer quality of life. Participants who began to provide care for more than 10 h weekly or care that was sometimes or often burdensome experienced declines in their quality of life. These findings are in line with previous work that has shown that entry into caregiving is associated with reduced quality of life (Rafnsson et al. 2017; Yiengprugsawan et al. 2016). No recoveries in quality of life occurred if carers continued providing care for more than one wave, indicating that similarly to previous studies no adaptation was observed (Lacey et al. 2019; Rafnsson et al. 2017). Simultaneously, our findings do not readily support a cumulative effect of sustained caregiving, as would be predicted by the “wear and tear” hypothesis (Townsend et al. 1989), since no additional declines were observed for those providing care at consecutive waves. Nevertheless, sustained caregiving might further erode quality of life, as the participants reporting lowest levels of quality of life were those who repeatedly provided care, which was similar to other studies (Lacey et al. 2019; Yiengprugsawan et al. 2016).

Strengthening the evidence from earlier smaller studies (Bond et al. 2003; Seltzer and Li 2000), and in contrast to other studies not detecting changes (Rafnsson et al. 2017; Yiengprugsawan et al. 2016), we were able to observe that once participants ceased providing care, their quality of life improved. The implications are stark, given that cessation of care provision may result from institutionalization or death of the care receiver, suggesting that the relief from care stressors outweighs the grief and emotional hardships linked to these traumatic life events in its effect on quality of life. These findings are in line with the theory of role captivity, since caregivers who face substantial burden may have increasing feelings of being confined in the less mutual role of carer which has gradually detached them from a previous more reciprocal role, such as partner or child (Aneshensel et al. 1993, 2004). Therefore, cessation of caregiving may be related to reduction in role captivity and other secondary stressors in the caregiver stress process, despite full recovery not being reached due to lingering negative impacts of prior caregiving and the possible loss of a family member (Aneshensel et al. 1993).

The lack of gender differences in the caregiving-quality of life relationship observed in our study is in contrast to some prior work (Bookwala 2009; Hansen et al. 2013; Hirst 2005), but in agreement with a previous study using data from Denmark and Sweden (Broek and Grundy 2018). The influence of gender in Sweden appears to be in exposing women more often to the task of informal caregiving per se, as well as to caregiving that is more time-consuming and burdensome (Gallicchio et al. 2002; Pinquart and Sörensen 2006). While levels of gender equality in Sweden are high compared to other countries worldwide, it is overwhelmingly women who make up these high-risk carer groups. The implication is that trends in re-familialization of eldercare in Sweden may deepen gender inequalities among older people in quality of life.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

This large community-based study provided the opportunity to observe dose-dependent relationships and small associations between caregiving and quality of life with a high degree of precision. SLOSH is a panel study which enabled the evaluation of caregiving states and transitions on overall levels and change in CASP-19. A diverse range of longitudinal modelling approaches, including FE modelling, was used and a range of controls included in order to reduce the likelihood that third variables, such as health status, were confounding the relationship between caregiving and quality of life. Even after inclusion of depressive symptoms (a variable which is also a likely mediator of the detrimental effects of caregiving on quality of life), we were able to observe effects of caregiving upon quality of life. The use of these robust approaches suggests that caregiving, particularly when it is time-consuming or burdensome, is causing lower quality of life.

A major strength of this study is its use of the CASP-19 scale, a measure with strong theoretical foundations for the assessment of quality of life among increasingly healthy older people (Hyde et al. 2003). Other quality of life scales measure older adults’ quality of life exclusively from the perspective of objective indicators such as their health, ignoring the capacities older people have to live fulfilling lives despite less-than-optimum health (Higgs et al. 2003). In contrast, CASP-19 measures the fulfilment of basic human needs alongside more active and reflective aspects of human nature, specifically measuring choice, autonomy, self-expression and pleasure (Gilleard and Higgs 2010; Higgs et al. 2003). Quality of life is measured in terms of individuals’ freedom to reflexively shape their biographies in ways that are meaningful to them, making it a particularly suitable measure for evaluating the impact of caregiving. By including 19 items, the scale is able to capture the complexity of the multidimensional quality of life concept and has good measurement properties compared to single-item scales.

However, the study has some limitations. First, while the CASP-19 measure is intended to be distinct of individual or contextual factors that influence quality of life, it includes an item about family responsibilities impeding participation in preferred activities. After excluding this item, most results were similar, although reduced in size and some coefficients were no longer significant at the 95% significance level, since reductions to self-chosen activities are likely to be one mechanism through which caregiving affects quality of life. Second, the study sample was out of work or working at low intensity, but drawn from broader sample of people in early old age who previously have had relatively close ties to the labour market. Consequently, the findings are not generalizable to those who have been out of the labour market for a lengthy period or who are providing care while working full-time. Specifically concerning this latter group, our finding that providing a low number of hours of care had no effect on quality of life might change since any negative effects might be strengthened by role conflict among caregivers in full-time work or positive effects by paid work offering some respite from caregiving. Selective attrition from SLOSH has taken place, with respondents more likely than non-respondents to be female, older, Swedish-born, married and to have university qualifications. This is particularly relevant for underrepresented ethnic minority groups, who may be more likely to provide informal care and experience restricted access to social care services (Greenwood et al. 2015). Third, information was not available in SLOSH about characteristics of the care receiver (e.g., nature of disability or illness, whether co-resident) or about which tasks are performed (e.g., being on call, administrative tasks, personal care), precluding analysis of these aspects in relation to quality of life. Lastly, measures of care were only provided at each wave. Consequently, it was not possible to ascertain behaviour between waves, e.g., whether a person providing care at two consecutive waves had been providing care continuously during the intervening period.

4.2 Implications and Conclusion

One important contribution is the diversity of impact of providing care upon individual quality of life. While many carers do not experience observable reductions in quality of life, people who are providing at least 10 h of care per week and who report caregiving to be burdensome are an at-risk group to whom resources should be targeted. Future studies should take heed of the fact that merely comparing carers against the general population may ignore diversity among carers and lead to substantially weaker or even null findings. Further work could also explore which factors exacerbate perceived burden among carers, and population-based survey that collect information on caregiving should include scales of care burden as herein we showed care burden to be closely related to intensity of care. Since the detrimental effect of caregiving on quality of life becomes more marked when caregiving is more time-consuming and burdensome, social care systems could target help to such carers through policies such as respite care or high quality institutional care. Our findings resonate with suggestions that more universal social care systems might support quality of life among older adults, since more generous welfare states have a higher prevalence of informal caregiving overall yet a lower prevalence of informal carers providing intensive care, of more than 10 h per week (Verbakel et al. 2017). This is also in agreement with findings from Nordic countries showing that policy changes away from universal care models have a detrimental impact on quality of life among older caregivers (Broek and Grundy 2018).

Providing informal care is an increasingly common activity in early old age, as parents, parents-in-law and spouses enter a stage in life when rates of chronic and debilitating illness are more common. Informal caregiving has substantial negative impacts on quality of life in the third age, by limiting possibilities for choice, autonomy, self-expression and pleasure in later life.

References

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Andreß, H.-J., Golsch, K., & Schmidt, A. W. (2013). Applied panel data analysis for economic and social surveys. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-32914-2.

Aneshensel, C. S., Botticello, A. L., & Yamamoto-Mitani, N. (2004). When caregiving ends: The course of depressive symptoms after bereavement. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 45(4), 422–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650404500405.

Aneshensel, C. S., Pearlin, L. I., & Schuler, R. H. (1993). Stress, role captivity, and the cessation of caregiving. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34(1), 54–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137304.

Ang, R. P., & Jiaqing, O. (2012). Association between caregiving, meaning in life, and life satisfaction beyond 50 in an Asian sample: Age as a moderator. Social Indicators Research, 108(3), 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9891-9.

Bond, M. J., Clark, M. S., & Davies, S. (2003). The quality of life of spouse dementia caregivers: Changes associated with yielding to formal care and widowhood. Social Science & Medicine, 57(12), 2385–2395. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00133-3.

Bookwala, J. (2009). The impact of parent care on marital quality and well-being in adult daughters and sons. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B(3), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp018.

Borg, C., & Hallberg, I. R. (2006). Life satisfaction among informal caregivers in comparison with non-caregivers. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 20(4), 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00424.x.

van den Broek, T., & Grundy, E. (2018). Does long-term care coverage shape the impact of informal care-giving on quality of life? A difference-in-difference approach. Ageing & Society. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18001708.

Brown, R. M., & Brown, S. L. (2014). Informal caregiving: A reappraisal of effects on caregivers. Social Issues and Policy Review, 8(1), 74–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12002.

Carers, U. K., & Age, U. K. (2015). Caring into later life: The growing pressure on older carers. London, UK: Carers UK & Age UK.

Chappell, N., & Blandford, A. (1991). Informal and formal care: Exploring the complementarity. Ageing & Society, 11(3), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X00004189.

Chen, L., Fan, H., & Chu, L. (2019). The hidden cost of informal care: An empirical study on female caregivers’ subjective well-being. Social Science & Medicine, 224, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.051.

Dahlberg, L., Demack, S., & Bambra, C. (2007). Age and gender of informal carers: A population-based study in the UK. Health & Social Care in the Community, 15(5), 439–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00702.x.

del-Pino-CasadoCardosaLópez-MartínezOrgeta, R. M. R. C. V. (2019). The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in carers of older relatives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 14(5), e0217648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217648.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 94–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001.

Gallicchio, L., Siddiqi, N., Langenberg, P., & Baumgarten, M. (2002). Gender differences in burden and depression among informal caregivers of demented elders in the community. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(2), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.538.

Gilleard, C. J., & Higgs, P. F. D. (2010). Aging without agency: Theorizing the fourth age. Aging & Mental Health, 14(2), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903228762.

Greenwood, N., Habibi, R., Smith, R., & Manthorpe, J. (2015). Barriers to access and minority ethnic carers’ satisfaction with social care services in the community: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative literature. Health and Social Care in the Community, 23(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12116.

Hansen, T., Slagsvold, B., & Ingebretsen, R. (2013). The strains and gains of caregiving: An examination of the effects of providing personal care to a parent on a range of indicators of psychological well-being. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0148-z.

Higgs, P. F. D., Hyde, M., Wiggins, R. D., & Blane, D. (2003). Researching quality of life in early old age: The importance of the sociological dimension. Social Policy and Administration, 37, 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00336.

Hirst, M. (1990s). Transitions to informal care in Great Britain during the 1990s. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 56(8), 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.56.8.579.

Hirst, M. (2005). Carer distress: A prospective, population-based study. Social Science & Medicine, 61(3), 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.001.

Hollander, M. J., Liu, G., & Chappell, N. L. (2009). Who cares and how much? The imputed economic contribution to the Canadian healthcare system of middle-aged and older unpaid caregivers providing care to the elderly. Healthcare Quarterly, 12(2), 42–49.

Howe, A. L., Schofield, H., & Herrman, H. (1997). Caregiving: A common or uncommon experience? Social Science & Medicine, 45(7), 1017–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00017-8.

Hyde, M., Wiggins, R. D., Higgs, P. F. D., & Blane, D. (2003). A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging & Mental Health, 7(3), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786031000101157.

Jacobi, C. E., van den Berg, B., Boshuizen, H. C., Rupp, I., Dinant, H. J., & van den Bos, G. A. M. (2003). Dimension-specific burden of caregiving among partners of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology, 42(10), 1226–1233. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keg366.

Lacey, R. E., McMunn, A., & Webb, E. (2019). Informal caregiving patterns and trajectories of psychological distress in the UK household longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine, 49(10), 1652–1660. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002222.

Laslett, P. (1989). A fresh map of life: The emergence of the third age. London, UK: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Magnusson Hanson, L. L., Leineweber, C., Persson, V., Hyde, M., Theorell, T., & Westerlund, H. (2018). Cohort profile: The swedish longitudinal occupational survey of health (SLOSH). International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(3), 691–692i. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx260.

Magnusson Hanson, L. L., Westerlund, H., Leineweber, C., Rugulies, R., Osika, W., Theorell, T., et al. (2014). The Symptom Checklist-core depression (SCL-CD6) scale: Psychometric properties of a brief six item scale for the assessment of depression. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 42(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494813500591.

Marks, N. F., Lambert, J. D., & Choi, H. (2002). Transitions to caregiving, gender, and psychological well-being: A prospective US national study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(3), 657–667.

Matz-Costa, C., James, J. B., Ludlow, L., Brown, M., Besen, E., & Johnson, C. (2014). The meaning and measurement of productive engagement in later life. Social Indicators Research, 118(3), 1293–1314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0469-6.

McMunn, A., Nazroo, J., Wahrendorf, M., Breeze, E., & Zaninotto, P. (2009). Participation in socially-productive activities, reciprocity and wellbeing in later life: Baseline results in England. Ageing and Society, 29(05), 765. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X08008350.

National Alliance for Caregiving, & AARP Public Policy Institute. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Washington, DC: National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP.

Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583.

Pickard, L. (2015). A growing care gap? The supply of unpaid care for older people by their adult children in England to 2032. Ageing & Society, 35(01), 96–123. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000512.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 61(1), P33–P45. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.P33.

Platts, L. G. (2014). A life course study of quality of life at older ages in a French occupational cohort (PhD thesis). Imperial College London, London.

Quesnel-Vallée, A. (2007). Self-rated health: Caught in the crossfire of the quest for ‘true’ health? International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(6), 1161–1164. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dym236.

Rafnsson, S. B., Shankar, A., & Steptoe, A. (2017). Informal caregiving transitions, subjective well-being and depressed mood: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Aging & Mental Health, 21(1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1088510.

Ross, A., Lloyd, J., Weinhardt, M., & Cheshire, H. (2008). Living and Caring? An Investigation of the Experiences of Older Carers. London, UK. https://www.ilcuk.org.uk/images/uploads/publication-pdfs/pdf_pdf_89.pdf.

Roth, D. L., Fredman, L., & Haley, W. E. (2015). Informal caregiving and its impact on health: A reappraisal from population-based studies. The Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu177.

Roth, D. L., Perkins, M., Wadley, V. G., Temple, E. M., & Haley, W. E. (2009). Family caregiving and emotional strain: Associations with quality of life in a large national sample of middle-aged and older adults. Quality of Life Research, 18(6), 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9482-2.

Rozario, P. A., Morrow-Howell, N., & Hinterlong, J. E. (2004). Role enhancement or role strain Assessing the impact of multiple productive roles on older caregiver well-being. Research on Aging, 26(4), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504264437.

Seltzer, M. M., & Li, L. W. (2000). The dynamics of caregiving: Transitions during a three-year prospective study. The Gerontologist, 40(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/40.2.165.

Socialstyrelsen. (2014). Anhöriga som ger omsorg till närstående – Fördjupad studie av omfattning och konsekvenser [Relatives who give care to family members - In depth study of the scale and consequences] (p. 78). Socialstyrelsen.

StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

Townsend, A., Noelker, L., Deimling, G., & Bass, D. (1989). Longitudinal impact of interhousehold caregiving on adult children’s mental health. Psychology and Aging, 4(4), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.4.4.393.

Ulmanen, P., & Szebehely, M. (2015). From the state to the family or to the market?: Consequences of reduced residential eldercare in Sweden. International Journal of Social Welfare, 24(1), 81–92.

van den Berg, B., Fiebig, D. G., & Hall, J. (2014). Well-being losses due to care-giving. Journal of Health Economics, 35, 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.01.008.

Vanhoutte, B. (2012). Measuring Subjective Well-Being in Later Life: A Review (Working Paper). Manchester: The Cathie Marsh Centre for Census and Survey Research. https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/cmist/archive-publications/working-papers/2012/2012–06-Briefing%2520wellbeing%2520Bram%2520Vanhoutte_final.pdf.

Verbakel, E., Metzelthin, S. F., & Kempen, G. I. J. M. (2018). Caregiving to older adults: Determinants of informal caregivers’ subjective well-being and formal and informal support as alleviating conditions. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(6), 1099–1111. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw047.

Verbakel, E., Tamlagsrønning, S., Winstone, L., Fjær, E. L., & Eikemo, T. A. (2017). Informal care in Europe: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014) special module on the social determinants of health. European Journal of Public Health, 27(suppl_1), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw229.

Wahrendorf, M., & Siegrist, J. (2010). Are changes in productive activities of older people associated with changes in their well-being? Results from a longitudinal European study. European Journal of Ageing, 7(2), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0154-4.

Wiggins, R. D., Netuveli, G., Hyde, M., Higgs, P. F. D., & Blane, D. (2008). The evaluation of a self-enumerated scale of quality of life (CASP-19) in the context of research on ageing: A combination of exploratory and confirmatory approaches. Social Indicators Research, 89(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9220-5.

Yiengprugsawan, V., Leach, L., Berecki-Gisolf, J., Kendig, H., Harley, D., Seubsman, S., et al. (2016). Caregiving and mental health among workers: Longitudinal evidence from a large cohort of adults in Thailand. SSM - Population Health, 2, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.01.004.

Zaninotto, P., Breeze, E., McMunn, A., & Nazroo, J. (2013). Socially productive activities, reciprocity and well-being in early old age: Gender-specific results from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Journal of Population Ageing, 6(1–2), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-012-9079-3.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Kamprad Family Foundation (20180313) and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2017-00099 and 2012-1743). The authors thank Martin Hyde for discussions that contributed to the development of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

L. G. Platts has collaborations with the Swedish non-profit associations National Pensioners' Organisation and Pensionsrättvisa (Pensions Justice).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sacco, L.B., König, S., Westerlund, H. et al. Informal Caregiving and Quality of Life Among Older Adults: Prospective Analyses from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH). Soc Indic Res 160, 845–866 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02473-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02473-x