Abstract

In every social transaction there is an element of trust. The degree to which we trust others, called generalized trust, is assumed to benefit from interaction with different social groups. In the trust literature, it is opposed by particularized trust, which represents our mutual confidence in individuals close to us, for example, family members and friends. This study, based on a survey with 634 university students from Austria, questions the strict dichotomy between the two trust types. Our results advocate for a third, group determined type of trust. This additional trust dimension is measured by the number of groups individuals participate in. It changes fluently between particularized and generalized trust, depending on measures of group context, like frequency of interaction or group size. Our findings show that generalized trust increases with the number of groups one feels belonging to. People with less diverse social interaction, however, have more trust in their peers than in strangers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There are many influential contributions highlighting the significant role of trust in others for societal well-being (Knack and Keefer 1997; Guiso et al. 2000; Putnam 1995; Stephany 2020). But the measurement of mutual confidence in others is a topic of an ongoing and controversial scientific debate. The critique aims mainly at two points. First, is it generally possible to assess trust with on single question? The question of how much you can trust most people might be understood quite differently across and even within cultural boundaries (Delhey et al. 2011; Reeskens 2012). Secondly, it can be questioned whether generalized trust captures our willingness and capacity for social interaction, which is the parameter researchers are actually interested in. If the responses to the generalized trust question only reflect our attitudes towards foreigners or people outside of our everyday communities, as some scholars argue, then generalized trust would not be an appropriate approximation of our willingness for civic engagement. When levels of economic (Stephany 2017) or ethnic (Alesina and La Ferrara 2002) fragmentation are high, levels of generalized trust diminish, leading to unfavourable societal outcomes and further segregation (Stephany 2018; Alesina and Ferrara 2005). The less individuals perceive others in society to share living realities in terms of ethnic and economic identity, the less they share sentiments of trust with other members of society. At the same time, the trust towards individuals in high social and ethnic proximity remains unaffected by fragmentation (Alesina and La Ferrara 2002).

This issue has been discussed in greater detail by Uslaner (2001) who draws a clear distinction between two opposing concepts of trust—generalized and particularized trust: “the difference between generalized and particularized trust is similar to the distinction between ’bonding’ and ’bridging’ social capitalFootnote 1. We bond with our friends and people like ourselves. We form bridges with people who are different from ourselves” (p. 7). He explicitly links these concepts to group activity: ‘when we only have faith in some people, we are most likely to trust people like ourselves. And particularized trusters are likely to join groups composed of people like themselves—and to shy away from activities that involve people they don’t see as part of their moral community” (ibid.). This statement evokes the central hen-and-egg question of trust research: does trust emerge from engagement with others or is it rather a prerequisite for group interaction?

The study presented here analyses the relation between group participation and social trust in more detail by means of a questionnaire distributed to students at Vienna University of Economics and Business in summer 2015. The online survey asks the students about different dimensions of trust and group interactions, to reveal potential connections between them. Taking the evidence of the statistical models together, the results suggest that group interactions are positively associated to the different dimensions of generalized, group-based (Wollebaek et al. 2012), and particularized trust, which are highly interdependent. The positive effect of group interaction on generalized trust can be isolated by employing an instrumental-variable regression. In contrast to Uslaner’s hypothesis, the data do not provide evidence on a negative relation between particularized trust and group interactions.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows: in the next section, a literature review outlines the results of previous investigations on trust and group participation. Section 3 illustrates our hypotheses. Section 4 presents the data collected, the questionnaire, and the methods. Section 5 summarizes the results and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Literature Review

Despite the prominent role of trust in social capital literatureFootnote 2, empirical studies so far have failed to find a consensus on the distinction between different types of trust measures. The lines between generalized and particularized trust are sometimes blurred. Smith (2010), for example, summarizes findings on race and trust, by describing the connection between ethnicity and mutual confidence across three different types of trust, generalized, particularized and strategic trust. In the concept of strategic trust, actors assume that trustees will act in accordance with their rational interest.

The dichotomy of generalized and particularized trust is further enriched by other scholars (Hoyer and Monness 2016; Wollebaek et al. 2012). From the results of a factor analysis, stemming from 33 Swedish municipalities, Wollebaek et al. conclude that there exists a third type of confidence, community trust. This type of faith is neither completely generalized trust, nor particularized trust, but rather something in-between. Community trust is based on the fact of belonging to a spatially bound community or group. Of all three trust measures, the third trust type is shown to be most vulnerable to economic and ethnic fragmentation. We adapt this concept (Wollebaek et al. 2012) of group-based trust for our analysis.

In contrast, Uslaner (Uslaner 2010) argues in favour of the “classical” dichotomy between generalized trust, which is faith in strangers and particularized trust, as mutual confidence in one’s own “in-group”, which needs to be defined from a personal perspective. The definition of an “in-group”, however, largely depends on the probability to meet people, who are similar to us. The author links the two trust measures to bridging (generalized trust) and bonding (particularized trust) social capital. Furthermore, Uslaner also theorises about strategic trust, a concept he defines as the trust of person A in person B to accordingly perform a certain task.

Delhey et al. (2011) show that people distinguish at least in two different sets of social interactions and therefore two distinct groups of trust, in-group and out-group trust. In their cross country analysis, they state that “most people” in standard questions most commonly refer to out-groups. They acknowledge the subjectivity of the meaning of “most people”, but point out that the variation is driven by cultural differences rather than by individual perception. The radius is quite narrow in Confucian countries, wider in wealthy countries, and—in this particular case—relatively comparable across European societiesFootnote 3.

In light of recent findings (Wollebaek et al. 2012; Lundason and Wollebaek 2013; Stolle 2002), we question the strict dichotomy between generalized and particularized trust. Trust in ’most people’ reflects the attitude towards strangers (Freitag and Bauer 2013). Particularized trust represents the attitude towards people one knows personally. We are furthermore convinced that there is a distinct third type of trust, which is based on the relation towards groups and communities one shares an identity (like the church) or a common cause (like charities or political parties) with.

Table 1 summarises past contributions with quantitative analyses on group specific trust. While, some studies have investigated on how personal factors, such as education or generalized trust influence trust in one specific group, little research has been conducted on the assessment of trust in various types of group. Similarly, our paper contributes to the trust literature in addressing the question if trust emerges from engagement with others or is it rather a prerequisite for group interaction.

3 Research Hypothesis

Since the concepts of mutual confidence are fluent, we argue that there might be a sizeable overlap between three types of trust. The order of the trust types along the degree of context is clear. With increasing context to the reference group in question, individuals move from strangers (generalized trust) to group and community members (group trust) to friends and family (particularized trust).

Over the life course, we imagine trust to evolve gradually as the communities one trusts in become larger and less socially confined. a First, those individuals with high levels of particularized trust in small social circles, such as one’s family and friends, are likely to develop a trusting relationship to slightly larger and more abstract communities. Lastly, high generalized trust stems from the interaction with various groups. b Low levels of initial particularized trust limit the number of group interactions, subsequently, resulting in lower levels of generalized trust

It has been argued, on the one hand, that generalized trust can be encouraged by the interaction in diverse networks and groups. The more group interaction, the higher an individual’s level of generalized trust.Footnote 4 On the other hand, particularized trust is characterized by a reverse relationship with group interactions (Putnam et al. 1993; Iglic 2010). Individuals with singular contacts (in small and distinct groups) are expected to have high faith to the people ’of their own kind’ but not in strangers.

We assume that there is a directed relationship from particularized to generalized trust, mitigated by group participation, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Over the life course, we imagine trust to evolve gradually as the communities one trusts in become larger and less socially confined. First, those individuals with high levels of particularized trust in small social circles, such as one’s family and friends, are likely to develop a trusting relationship to slightly larger and more abstract communities. Subsequently, the more distinctly different groups an individual is member of, the higher her confidence in people in general is going to be: Generalized trust stems from diverse group interactions, rather than enabling them.

Based on the discussion of the literature about the relation between generalized and particularized trust as well as the connection to group participation, we develop the following hypotheses that are tested by analysing our survey data: We assume that group-specific confidence has distinctly different traits than generalized and particularized trust. H1 There are more than two distinct dimensions of trust. On an intermediate level of social context, mutual confidence in groups and its members builds a distinct third type of trust.

Measurement difficulties and problems of endogeneity have made it cumbersome to empirically assess the relationship and a direction between generalized trust and group participation. We postulate a relationship between the two concepts. H2 Generalized trust depends on group participation. Those individuals that participate in more groups exhibit a higher level of generalized trust on average.

In contrast to generalized trust, we assume group-specific trust to diminish with more group interactions. H3 The average group trust decreases with the number of groups.

Context, on the other hand, is assumed to be beneficial for group trust. The higher the degree of social context to a group, the more an individual is likely to have a strong confidence in its members. H4 Group trust increases with the context of a group, i. e. an individuals group trust is higher (a) for smaller groups and (b) those with more interactions.

Lastly, we assume a direction in the relationship between the trust types. Generalized trust is built up by particularized trust, rather than vice versa. This process is mitigated by group interaction. A narrative of the relationship is reflected in our last hypothesis. H5: Particularized trust is a prerequisite for group-specific confidence, while participation in many groups fosters generalized trust.

4 Data and Method

4.1 Data

The online questionnaire about trust and group participation which we distributed in summer 2015 is oriented at common surveys about trust and social capital and includes questions that have been found to reflect the most important determinants of trust in articles mentioned in the literature review. Besides demographic characteristics, the focus is on the different trust questions (general, colleagues, groups, friends, family) and on the groups the students are participating in. The list of all questions asked in the survey can be found in Table 1b. For the demographic variables, summary statisticsFootnote 5 are provided in Fig. 2d.

Often, researchers represent social capital with degrees of trust. Similarly, measures such as network size or cooperative norms are used to operationalize social capital (Stephany 2018). This study analyses trust itself without any approximation to social capital. We rather examine trust in the context of groups with different degrees of social confinement, ranging from family or friends to members of sports clubs or unions to “most people”, by asking the question: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful in dealing with people?”. Answers range on a Likert scale from 0 (no trust) to 10 (complete trust). Similarly, we replace the term “most people” with the respective group, in accordance with the practice of standardised surveys on interpersonal trustFootnote 6.

Slightly more than half of the participants are males (54%), while around two thirds are from Austria (67%, 16% are Germans). Nearly half of the participants indicate no specific religious denomination (45%) or state to be Roman-catholic (42%). The majority of the students lives in a relationship (60%). The median age of the group is 25 and their median disposable monthly income is 900 EUR. These demographics are in accordance with the expectations about such a homogeneous group of people like students at an Austrian business universityFootnote 7.

We acknowledge the potential limitations which come with the restriction of our sample, at the same time, we do not suspect them to undermine the robustness of our main empirical findingsFootnote 8.

4.2 The 2SLS Approach

One aim this analysis is to clarify the relationship between particularized, group-specific, and generalized trust. For example, it could be imagined that group-specific trust emerges from generalized trust, since individuals with high levels of confidence in others in general are likely to engage in trusting relationships within smaller subgroups of society. On the other hand, it is possible to argue that our level of generalized trust increases the more we build up trust in different distinct communities. At the same time, all trust concepts are influenced by personal trajectories, such as education, upbringing, or religion. A mutual dependence between the different trust concepts emerges.

The potential joint-determination of the trust concepts, as well as the mutual dependence circumvent an accurate estimation of coefficients with inferential statistics. The results of any inferential model which tries to directly explain one level of trust with another trust concept, can be jeopardised by endogeneity (Antonakis et al. 2014). In order to overcome the problematic issues of endogeneity, a two-stage least-squares (2SLS) regression analysis is carried out separately for each of the three trust types (Freitag and Traunmüller 2009; Wollebaek et al. 2012)Footnote 9.

In a first step, a level of generalized trust (GT) is estimated with the use of all possible personal explanatory variables (\(X_{1,\ldots ,n}\)) (1).

here only a subset (\(X_{k,\ldots ,m}\)) of the list of explanatory variables appears to be relevant for explaining the level of GT. In a second step, the fitted value of particularized trust (PT) is estimated with the use of its individual determinants (\(X_{1,\ldots ,m}\)) (2).

Lastly, the predicted values, \({\widehat{PT}}\), can be used in order to estimate the level of generalized trust together with the previously discovered determinants (3).

A consistent estimation is possible, since \({\widehat{PT}}\) is determined by confounding factors, which are not linked to generalized trust. In the wording of instrumental regressions, particularized trust is instrumented via its unique personal determinants. This instrumentation is in return likewise applied in the opposite direction.

In order to be considered suitable for an 2SLS approach (Antonakis et al. 2014) the instruments need to be validFootnote 10, must not have any explanatory power in the original equationFootnote 11, and lastly, should not be weakFootnote 12. The described approach is applied for all three trust measures, estimating the remaining two trust concepts in a 2SLS approach via their determinants on an individual level. In order to test for the adequacy of the 2SLS approach and the validity of the instruments applied, two different test statistics are consulted. The first statistic is the F-Statistic for the power of the instruments. The null hypothesis of the test assumes that the instruments applied are not strongly enough correlated with the explanatory variables so that the instruments would be weak. Secondly, the Sargan test examines the model for over-identification. Its null hypothesis assumes that the instruments are valid.

5 Results

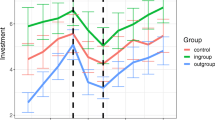

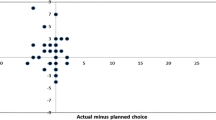

a Principal component analysis of trust variables: the trust dimensions are positive associated, but non-identical. b Trust and number of group participations: individuals with many group interactions show relatively higher levels of generalized trust. c Intensity of participation and group trust: group specific trust increases with group interaction and decreases with group size. d Summary statistics of demographic characteristics of the survey participants

Initially we regard a rather descriptive but reassuring finding. Figure 2a shows a dimensionality reduced version of the data in form of its first two principal componentsFootnote 13.

The red arrows, representing the loading of each variable in the two-dimensional space, confirm the positive association between the trust questions. All of them load high on component 1, but they differ considerably with respect to component 2. In particular, family and friends trust are loaded much higher on component 2 than the other dimensions. Besides that, group trust forms a distinct category different from trust in study colleagues and generalized trustFootnote 14.

Thus, we conclude our first hypothesis to be confirmed. There is a gradual but significant difference in the average level of trust from general to particular. Moreover, this result is in accordance with the idea of an identity-based trust; a form of faith in people that one does not necessarily know personally but who are perceived as more trustful than the general public.

But how does this finding differ between people who are engaged in many groups compared to those who are member in only one or no groups at all?

Figure 2b displays the average level of the trust variables against the number of groups. Interestingly, family and friends trust do not change with the number of groups. They constant for zero to five groupsFootnote 15. Particularized trust is, thus, clearly insensitive to group participation, since it is high for nearly all individuals in the survey and exhibits low variance. In comparison, group-based and generalized trust increase with the number of groups.

The positive relation between group participation and generalized trust is in accordance with hypothesis \(H_2\) and corroborates arguments in favour of a positive effect of group interaction on trust. The increasing level of group trust surprises. However, the effect is only moderate (and not significant, as shown by the KWallis-test statistic which equals a t-test statistic with multiple groups) and it is due to the mutual dependence mentioned earlier: Since high general trusters tend to show high levels of other trust dimensions as well, a potential negative relation between the number of groups and the average level of group trust is disguised. Therefore, we standardize the average group trust by the level of generalized trust for each individual and depict it on the same graph (on the right hand axis). This time, the negative effect becomes obvious. If one controls for generalized trust, the average level of group trust decreases significantly with higher number of groups, as presumed in the third hypothesis, \(H_3\).

What do these results tell us? First, those individuals with social interactions to more people, measured by the number of group memberships, show a higher level of mutual confidence. This justifies the importance of group interaction in fostering generalized trust, as hypothesized by leading social capital researchers. Secondly, those people who have fewer social interactions, i. e. only one group, show a higher relative level of group trust than those individuals that take part in a more various social circles. They are the “particularized trusters (who) are likely to join groups composed of people like themselves”, Uslaner (Uslaner 2002, p. 7) thought of.

Further insights about the group trust can be gained from the results presented in Fig. 2c. This illustration displays the relation of group trust to the intensity of group participation (left panel) and to the group size (right panel). The intensity of group interactions, measured by the frequency of participation, has a positive effect on group trust. At the same time, the level of group trust decreases with group size. This is in accordance with hypotheses \(H_4\) (a) and (b) and thus supports the claim that an increased group context leads to more trust to its members: Smaller group size or more frequent interaction lead to more identification with the groups’ members and thus to a higher level of identity-based trust.

The results described so far have been gained from the isolated consideration of the relation between single trust components and group participation. To get a better understanding about the interdependence of particularized and generalized trust and their connection to individual characteristics, it is necessary to apply the described 2SLS approachFootnote 16.

Since family trust is almost invariant we use friends trust instead as approximation for particularized trust, and we perform an additional regression for group trust divided by generalized trust. This leads to four OLS and four 2SLS models where each trust component is first regressed on personal (exogenous) characteristics. In a second step, those covariates that turned out to be significant in the OLS model are employed in the 2SLS model together with the fitted values of the three trust components. In this way it is possible to investigate potential trust spillovers while avoiding endogeneity issues.

Table 2 summarizes the results of all eight models. Considering the first four models, it turns out that the three trust components share only some foundations. For instance, a catholic background is found to be positively associated with trust in all models. To live in a relationship does also positively effect mutual confidence in all dimensions. However, other classical control variables like age, gender and income do not have a significant effect. This is due to the largely homogeneous sample in which most of the participants are students. There is also no substantial effect of the family background with respect to parental education, the size of the municipality in which an individual grew up, and the number of times one has moved into other cities/regions/countries. While some of these variables are significant for single trust components, the effect is not very robust. Exceptions are a high level of an individuals’ own and her father’s education (master degree), which positively effects group trust (Stephany 2018).

More revealing are those variables that measure social interaction. While the self assessed evaluation on the intensity of social interaction (social) has a positive (but not consistently significant) effect on the whole trust spectrum, the participation in larger groups is associated with a lower group trust. Thus, the result derived in Fig. 2c is robust and hypothesis \(H_4\) about the relationship between group size and group trust is confirmed.

Those variables that have a significant effect in the OLS regressions are, in a second step, used as control variables in another regression on the trust components. This time, the fitted values of the outcome variables from the OLS regressions are added as additional explanatory variables to the model. These fitted values are no longer mutual dependent to other variables in the model, since their relation to the controls has been estimated by the first step regression. Therefore, the second stage regressions allow to investigate a potential trust spillover and to determine the effect of group interaction on trust. The statistics indicate that the respective instruments are both strong and valid, i.e. they do not over-identify the model and have only a limited correlation with the explanatory variables.

In contrast to previous studies (Freitag and Traunmüller 2009; Wollebaek et al. 2012) we find significant trust spillovers both from particularized (friends) trust to generalized trust and vice versa. The magnitude of the coefficients suggest that generalized trust is more strongly impacted by particularized trust, than the other way around. There is also a spillover from friends to group trust, but, group trust does not have a significant effect on generalized trust on top of the influence of particularized trust. However, the results confirm our hypotheses with respect to the number of groups an individual is participating in on the average level of trust. As shown in model 7, the higher the number of groups, the higher is the average level of generalized trust. Additionally, the constructed relative group trust (model 8) decreases with the number of groups. Moreover, bigger groups have a negative effect on group and friends trust as indicated in model 5 and 6, beyond the effect of trust spillovers.

As a consequence, we conclude hypothesis \(H_5\) to be confirmed, as well. On the one hand, group trust is positively linked with particularized trust and not with generalized trust. On the other hand, the more groups and individual participates in, the higher the level of generalized trust. The results about the relationship between group interaction and trust can be summarized as follows: first, there are more than two dimensions of trust. While there are positive associations between the different trust dimensions, the distribution of the responses to the five trust questions that have been asked about in the survey suggest that there is a category of identity-based trust as an additional dimension between generalized trust and particularized trust. Secondly, it is presumed that the participation in different groups is correlated with the average level of generalized and particularized trust as well as trust in the specific group. This relationship is validated by the data: there is a positive association between the number of groups one is participating in and the average level of generalized trust. In other words, people with more social interactions have indeed higher trust in people in general. Moreover, the group context affects the level of group trust. Smaller groups in which an individual is participating on a regular basis are trusted more than bigger groups with less interactions. Despite this, the hypothesized negative relation between the number of groups and the average level of particularized trust can not be confirmed by the data. The results indicate that particularized trust (rather than generalized trust) is an important prerequisite for group trust. The number of group interactions, on the other hand, has a positive association with generalized trust. Thus, the effect of group interaction on the different trust components can be detected beyond personal covariates and the inherent effect of trust spillovers.

6 Conclusions

Generalized trust is believed to be an important element of social capital. However, its internal validity and its power of representing social capacities for cooperation have been questioned. Generalized trust, in contrast to particularized trust, is believed to be associated with interactions in various networks and in mutual dependence with group interaction. Our findings support the assumption that generalized trust increases with the number of groups one feels belonging to and show that group specific trust is particularly high for individuals with only few group interactions.

Based on previous investigations (Wollebaek et al. 2012; Freitag and Bauer 2013), we question the strict dichotomy between particularized and generalized trust and show that a third type of identity-based or group trust needs to be considered. This kind of trust reflects the faith in group members. The concept of group trust overlaps with the previous two trust types. It tends more towards a family/friend-type trust the smaller the respective group is or the more often one interacts. The larger the group and the less frequent the interaction, the more group trust coincides with the generalized type of trust in most people.

The new concept of group trust is of particular importance when judging the effects of ethnic fragmentation or social exclusion on mutual confidence. Group trust is most likely to suffer from phenomena of ethnic or economic segregation (Wollebaek et al. 2012; Stephany and Braesemann 2017). It could well be that many of the past investigations concerning inequality or ethnic fragmentation and generalized trust have only captured parts of the diminishing effects segregation actually has on group based trust. This trust measure deserves more attention in social monitoring and policy interventions. Trust in strangers builds on experience. Policy makers should be aware of the fluent and hierarchical structure of the continuum of trust types. In order to encourage trust in people in general, one must start with supporting the engagement in small and potentially local social groups.

Our study examines a relatively homogeneous group, in terms of socio-economic characteristics, such as age, education or income. This limits the generalizability of our findings. At the same time, based on previous findings (Stephany 2017), we expect a more heterogeneous sample to show more larger differences in trust and group participation. Hence, the homogeneity of our sample should strengthen the validity of our findings. We expect them to be stronger in a setting with more participants of more heterogeneous background.

The study presented here considers only the mere number of group participation. It does not account for potentially varying effects of different group types. While the type of group has been assessed in the survey, the sample of 634 university students, how homogeneous it appears with respect to characteristics like age and income, is still too heterogeneous to immediately investigate the trust differences of individual groups. Even if all survey participants are students at the same university, the online questionnaire was distributed to all university members and it was not possible to identify specific groups with enough members to analyse these groups directly.

This gap could be filled by future research. Investigations on smaller groups of students with identifiable personal interactions could provide insights about the network centrality of individuals, their interaction to concrete groups, and the relation to their level of generalized trust. In order to investigate the effect of different group types (charity vs. sport vs. political organization) it would also be worthwhile to a consider larger sample involving more heterogeneous people with diverse group interactions.

Notes

In the trust literature, generalized trust is often used to quantify a form of social capital. We abstain from conceptualising social capital with trust, as generalized trust itself has shown to have beneficial effects on societal well-being (Knack and Keefer 1997; Guiso et al. 2000; Putnam 1995), while the conceptualisation of social capital has been criticised on many fronts.

Thomson Reuters’ Social Science Citation Index lists more than 1.700 articles on the topic “social capital and trust” published in the last 10 years. Thus, the articles mentioned in this section about the role of trust are inevitably only a small excerpt of all the numerous applications of trust within social science research. However, the selection of topics listed here already emphasises the significant attention trust and social capital have enjoyed recently.

In this investigation, the generalised trust question (see Table 1b) has been extended to members of family, friends, colleagues, and group members. The validity of this extension has been confirmed by past contributions: When shifting from known trustees, e.g., family and friends, to abstract counterparts, e.g., people in general, assessments of mutual benevolent behaviour and risk remain intact (Lundmark et al. 2015; Reeskens 2012; Delhey et al. 2011)

This has been shown on a regional level for the case of Switzerland (Freitag et al. 2009).

Further information about the survey, the raw data and code from which the results of the analysis have been drawn can be requested from the authors.

See the World Value Survey, the European Social Survey or the General Social Survey.

The high share of German students is obvious since Vienna is a very popular place to study for German students. With respect to the religion: despite Austria’s Roman-catholic history, the share of religious people in the young generation is not very high.

We consult the 2014 European Social Survey. The overall Austrian population, a sub-sample with at least higher secondary education, and a further, younger (less than 35 years old) sub-sample with high education are compared according to their levels of generalized trust. Like for our sample, the young and well-educated in the European census show a slightly higher level of generalized trust on average, which is more densely confined around the upper third of the trust scale. This observation, however, rather underlines the robustness of our results. In statistical inference, a more disperse outcome variable would presumably be associated with findings of even stronger statistical significance.

Apparently, these two studies are the only ones we could find which apply this approach. This is particularly interesting, since there are other articles available that empirically investigate the relationship between the different trust components that do not seem to take the problem of mutual dependence into account (Newton and Zmerli 2011; Delhey and Welzel 2012; Crepaz et al. 2014).

The instrument cannot be correlated with the error term of the original explanatory equation.

For example, the only way in which an instrument can effect generalized trust is via particularized trust.

The instrument must be correlated with the endogenous explanatory variable generalized trust.

The five-dimensional space of all single trust questions is projected into a two-dimensional space: the first dimension or principal component is a linear combination of all variables such that it maximizes the variance of the data and the second component is orthogonal to the first component. Together, both components capture 72.5% of the overall variance.

The principal component analysis provides only a first illustration of the data, since it does not control for the effect of mutual dependence (in contrast to the 2SLS models described at a later stage), i.e. the fact that high trusters exhibit high levels of all trust dimensions simultaneously.

The small decline for three groups is an outlier due to the small number of people who have named only three groups.

Despite the ordinal character of the trust questions on a scale from zero to ten, we did not use regression models designed particularly for ordinal scaled variables, since the question design in form of a Likert scale with labelled endpoints and an unlabelled interval in between is seen as a way to transform an ordinal variable into a quasi-interval scaled variable. For more on this consider the discussion on www.researchgate.com (Shapira 2014; Bell 2014).

References

Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trusts others? Journal of Public Economics, 85(2), 207–234.

Alesina, A., & Ferrara, E. L. (2005). Ethnic diversity and economic performance. Journal of Economic Literature, 43(3), 762–800.

Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2014). Causality and endogeneity: Problems and solutions. In D. Day (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of leadership and organizations (pp. 93–117).

Bakker, L., & Dekker, K. (2012). Social trust in urban neighbourhoods: the effect of relative ethnic group position. Urban Studies, 49(10), 2031–2047.

Bell, Reginald (2014, June 1). Is a Likert-type scale ordinal or interval data? Message posted at https://www.researchgate.net/post/Is_a_Likert-type_scale_ordinal_or_interval_data.

Crepaz, M. M., Polk, J. T., Bakker, R. S., & Singh, S. P. (2014). Trust matters: The impact of ingroup and outgroup trust on Nativism and Civicness. Social Science Quarterly, 95(4), 938–959.

Delhey, J., Newton, K., & Welzel, C. (2011). How general is trust in “most people”? Solving the radius of trust problem. American Sociological Review, 76(5), 786–807.

Delhey, J., & Welzel, C. (2012). Generalizing trust: how outgroup-trust grows beyond ingroup-trust. World Values Research WVR, 5(3), 46–69.

Freitag, M., & Bauer, P. C. (2013). Testing for measurement equivalence in surveys dimensions of social trust across cultural contexts. Public Opinion Quarterly, 77(S1), 24–44.

Freitag, M., Grießhaber, N., & Traunmüller, R. (2009). Vereine als schulen des vertrauens? Eine empirische analyse zur zivilgesellschaft in der schweiz. Swiss Political Science Review, 15, 495–527.

Freitag, M., & Traunmüller, R. (2009). Spheres of trust: An empirical analysis of the foundations of particularised and generalised trust. European Journal of Political Research, 48(6), 782–803.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2000). The role of social capital in financial development. National Bureau of Economic Research: Technical Report.

Hoyer, H. C., & Monness, E. (2016). Trust in public institutions-spillover and bandwidth. Journal of Trust Research, 6, 1–16.

Iglic, H. (2010). Voluntary associations and tolerance: An ambiguous relationship. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(5), 717–736.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly journal of economics, 112, 1251–1288.

Lundason, S. W., & Wollebaek, D. (2013). Diversity and community trust in Swedish local communities. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 23(3), 299–321.

Lundmark, S., Gilljam, M., & Dahlberg, S. (2015). Measuring generalized trust: An examination of question wording and the number of scale points. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(1), 26–43.

Meier, S., Pierce, L., Vaccaro, A., & La Cara, B. (2016). Trust and in-group favoritism in a culture of crime. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 132, 78–92.

Newton, K., & Zmerli, S. (2011). Three forms of trust and their association. European Political Science Review, 3, 169–200.

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78.

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. Y. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Reeskens, T. (2012). But who are those “most people” that can be trusted? Evaluating the radius of trust across 29 European societies. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 703–722.

Shapira, Stav (2014, December 7). What is the “right” regression model to use when my dependent variable is rated on a 7 point Likert scale? Message posted at https://www.researchgate.net/post/What_is_the_right_regression_model_to_use_when_my_dependent_variable_is_rated_on_a_7_point_Likert_scale.

Shareef, M. A., Kapoor, K. K., Mukerji, B., Dwivedi, R., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2019). Group behavior in social media: Antecedents of initial trust formation. Computers in Human Behavior, 105, 106225.

Smith, S. S. (2010). Race and trust. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 453–475.

Stephany, F., & Braesemann, F. (2017). An exploration of wikipedia data as a measure of regional knowledge distribution. In International Conference on Social Informatics, Springer, pp. 31–40.

Stephany, F., Braesemann, F., & Graham, M. (2020). Coding together–coding alone: the role of trust in collaborative programming. Information, Communication & Society, 1–18.

Stephany, F. (2017). Who are your joneses? Socio-specific income inequality and trust. Social Indicators Research, 134(3), 877–898.

Stephany, F. (2018). It deepens like a coastal shelf: Educational mobility and social capital in Germany. Social Indicators Research, 142, 1–31.

Stephany, F. (2020) It’s not only size that matters: Determinants of Estonia’s E-Governance Success. Electronic Government, An International Journal, 16(1), 1.

Stolle, D. (2002). Trusting strangers—the concept of generalized trust in perspective. Austrian Journal of Political Science, 31(4), 397–412.

Uslaner (2001). Trust as a moral value. In D. Castiglione, J. W. Van Deth, & G. Wolleb (Eds.), The handbook of social capital (2008) (pp 101–122). Oxford University Press on Demand.

Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Uslaner, E. M. (2010). Segregation, mistrust and minorities. Ethnicities, 10(4), 415–434.

Wollebaek, D., Lundason, S. W., & Tragardh, L. (2012). Three forms of interpersonal trust: Evidence from Swedish municipalities. Scandinavian Political Studies, 35(4), 319–346.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Braesemann, F., Stephany, F. Between Bonds and Bridges: Evidence from a Survey on Trust in Groups. Soc Indic Res 153, 111–128 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02471-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02471-z