Abstract

In countries characterized by large territorial differences in living standards, indicators of relative poverty measured at the national level might hide significant heterogeneities in the experience of individual households. We propose a relative indicator of poverty to be computed at the local level and to be added to the standard national poverty indicators. In fact, the greater the distance between local and national relative poverty, the more heterogeneous are contexts within the same country, hence requiring heterogeneous and specific policies at the local level to be added to nationwide ones. To show the usefulness of this additional indicator, we offer an application to young households in three provinces of North-Western Italy, the richest area in the country. Thanks to the additional indicator, we show that the poverty of households with children, mostly living in metropolitan areas or small towns, emerges only when observing a “local relative” measure of poverty. We conclude by discussing the gains of our proposed indicator for local policy interventions, to be added to nationwide policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We refer to the year 2013, for comparability with the dataset of our analysis (see Sect. 4).

Other scales of equivalence, such as OECD, take into account both the number and age of members in the household.

In defining the measurement of absolute poverty, relevance is given to the possibility of applying economies of scale in purchasing many goods and services considered to be fundamental. Generally, multiplicative coefficients are adopted that summarize the effect of saving/not saving while purchasing.

The prices underlying the definition of the monetary value of the basket corresponding to absolute poverty are differentiated according to their geographical distribution, using the lowest prices in all provincial capitals that participated in calculating the national price index. This takes into account the various kinds of commercial distribution found nationwide and defines the lowest price «within the type of distribution known as “hard discount”, the one found in modern distribution (hypermarkets, supermarkets, department stores, businesses with branches or chains of stores) and the one used in traditional distribution (corner stores, traditional shops, consumer cooperatives, street markets, other)» (Istat 2009, 71).

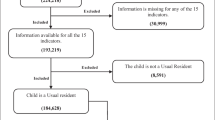

ArchIMEDe data are available at Istat Adele Lab, https://www.istat.it/adele/ListaRilevazioni.

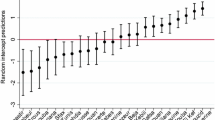

Except in three cases where they are slightly lower (households with three or four members living in metropolitan areas and households with three members living in large municipalities).

References

Aassve, A., Cottini, E., & Vitali, A. (2013). Youth prospects in a time of economic recession. Demographic Research, 29(36), 949–962.

Aassve, A., Iacovou, M., & Mencarini, L. (2006). Youth poverty and transition to adulthood in Europe. Demographic Research, 15(2), 21–50.

Atkinson, A. (1998). Poverty in Europe. Oxford: Blackwell.

Atkinson, A. B., & Bourguignon, F. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of Income Distribution (Vol. II). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Atkinson, A. B., Guio, A. C., & Marlier, E. (2017). Monitoring social inclusion in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Ayllón, S. (2015). Youth poverty, employment, and leaving the parental home in Europe. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(4), 651–676.

Bartus, T. (2005). Estimation of marginal effects using margeff. Stata Journal, 5(3), 1–23.

Brady, D., & Burton, L. M. (Eds.). (2016). The Oxford handbook of the social science of poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brandolini, A., Magri, S., & Smeeding, T. M. (2010). Asset-based measurement of poverty. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(2), 267–284.

Burtless, G. (2012). Demographic transformation and economic inequality. In S. Wiemer, B. Nolan, & T. M. Smeeding (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality (pp. 435–454). New York: Oxford University Press.

Cahn, N., Carbone, J., DeRose, L. F., & Wilcox, W. B. (Eds.). (2018). Unequal family lives. Causes and consequences in Europe and in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carbonaro, G. (1985) Nota sulle scale di equivalenza, in Commissione di indagine sulla povertà e sull’emarginazione. In CIES. (Eds.), Primo rapporto sulla povertà in Italia. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato.

Corbetta, P. (2003). Social research: Theory, methods and techniques. London: Sage.

Dagum, C., & Costa, M. (2004). Analysis and measurement of poverty. Univariate and multivariate approaches and their policy implications. A case study: Italy (pp. 221–271). Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag HD.

Darvas, Z. (2019). Why is it so hard to reach the EU’s poverty target? Social Indicators Research, 141(3), 1081–1105.

Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., Kalil, A., & Ziol-Guest, K. (2012). The importance of early childhood poverty. Social Indicators Research, 108, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9867-9.

Eurostat. (2016). Eurostat regional yearbook (2016th ed.). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Fernández-Macías, E., & Vacas-Soriano, C. (2017). Income inequalities and employment patterns in Europe before and after the Great Recession. Luxembourg: Eurofound.

Filandri, M., Nazio, T., & O’Reilly, J. (2019). Youth transitions and job quality: How long should they wait and what difference does the family make? In J. O’Reilly, J. Leschke, R. Ortlieb, M. Seeleib-Kaiser, & P. Villa (Eds.), Youth labour in transition: Inequalities, Mobility, And Policies in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Filandri, M., Pasqua, S., & Struffolino, E. (2020). Being working poor or feeling working poor? The role of work intensity and job stability for subjective poverty. Social Indicators Research, 147, 781–803.

Fisher, M. (2005). On the empirical finding of a higher risk of poverty in rural areas: Is rural residence endogenous to poverty? Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 30(2), 185–199.

Foster, J. (1998). Absolute versus relative poverty American economic review. American Economic Association, 88(2), 335–341.

Garofalo, G. (2014). Il Progetto ArchIMEDE obiettivi e risultati sperimenali, Istat. Working papers, 9.

Gelman, A., Carlin, J. B., Stern, H. S., & Rubin, D. B. (2013). Bayesian data analysis (3rd ed.). London: CRC Press.

Giarda, E., & Moroni, G. (2018). The degree of poverty persistence and the role of regional disparities in Italy in comparison with France, Spain and the UK. Social Indicators Research, 136(1), 163–202.

Giusti, C., Masserini, L., & Pratesi, M. (2017). Local comparisons of small area estimates of poverty: An application within the Tuscany Region in Italy. Social Indicators Research, 131(1), 235–254.

Hagenaars, A., & de Vos, K. (1988). The definition and measurement of poverty. The Journal of Human Resources, 23(2), 211–221.

Haveman, R., Blank, R., Moffitt, R., Smeeding, T., & Wallace, G. (2015). The war on poverty: Measurement, trends, and policy. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 34(3), 593–638.

Istat. (2009). La misura della povertà assoluta (p. 39). Istat: Metodi e norme.

Istat. (2015). Poverty in Italy year 2013. Press release: Istat. https://www.istat.it/en/archivio/128451.

Istat. (2018). Poverty in Italy year 2017. Press release: Istat. https://www.istat.it/en/archivio/217653.

Jenkins, S. P., & Van Kerm, P. (2014). The relationship between EU indicators of persistent and current poverty. Social Indicators Research, 116(2), 611–638.

Kangas, O. E., & Ritakallio, V.-M. (2007). Relative to what? Cross-national picture of European poverty measured by region, national and European standards, European Societies, 9(2), 119–145.

Kingdon, G. G., & Knight, J. (2006). Subjective well-being poverty vs. income poverty and capabilities poverty? The Journal of Development Studies, 42(7), 1199–1224.

Lemmi, A., Grassi, D., Masi, A., Pannuzi, N., & Regoli, A. (2019). Methodological choices and data quality issues for official poverty measures: Evidences from Italy. Social Indicators Research, 141(1), 299–330.

Madden, D. (2000). Relative or absolute poverty lines: A new approach. Review of Income and Wealth, 46(2), 181–199.

Marlier, E., & Atkinson, A. B. (2010). Indicators of poverty and social exclusion in a global context. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(2), 285–304.

Musterd, S., Murie, A., & Kesteloot, C. (Eds.). (2006). Neighbourhoods of poverty: Urban social exclusion and integration in Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. T. (1996). Resources, deprivation and poverty. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Petsimeris, P., & Rimoldi, S. (2015). Socio-economic divisions of space in Milan in the post-Fordist era. In T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham, & S. Musterd (Eds.), Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities. East meets west. Abingdon: Routledge.

Shapiro, I., & Trisi, D. (2017). Child poverty falls to record low, comprehensive measure shows stronger government policies account for long-term improvement. Washington: CBPP.

Verrecchia, F. (Ed.). (2019). Dati Amministrativi, Metodi e Statistiche per le Politiche Territoriali. Roma: FrancoAngeli.

Wallgren, A., & Wallgren, B. (2014). Register-based statistics: Administrative data for statistical purposes (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley.

Zhang, L. C. (2012). Topics of statistical theory for register-based statistics and data integration. Statistica Neerlandica, 66(1), 41–63.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible thanks to the analysis activity carried out in the framework of the SPoT project. We would like to thank the participants of the conference on “Well-being and Territory: Methods and Strategies”, which was held on 23 and 24 May 2019 in Ascoli Piceno, for the discussion and their suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ballabio, S., Filandri, M., Pacelli, L. et al. Poverty of Young People: Context and Household Effects in North-Western Italy. Soc Indic Res 161, 819–842 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02409-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02409-5