Abstract

In the present study we examined care-related and demographic predictors of well-being among 225 (formerly) homeless clients of a Dutch organisation providing shelter services and ambulatory care (shelter facility). The role of social participation as a mediator was considered. Social participation is important for homeless people, as they are often socially isolated. Moreover, social participation enhances well-being and induces happiness. In this study we used the following care-related predictors: (1) participation in various group activities in the shelter facility, and (2) client’s experiences with care, such as their satisfaction with the social worker and the shelter facility. Additionally, age and education level were included as demographic predictors. Results from Structural Equation Modelling show that the client’s experiences with care and education level are predictors of well-being with a mediating role for social participation, and that participation in activities at the shelter facility is a direct predictor of well-being. However, age is not significantly related to social participation or well-being. We suggest that interventions for the homeless should be based on a combination of individual and group approaches. Special attention should be given to the client–worker relationship. We also recommend that vulnerable children are provided with solid education, and we call for research into the cost-effectiveness of group-based interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social participation, defined as ‘involvement in activities that provides social interaction with others in society or the community’ (Levasseur et al. 2010, p. 2146), is a strong predictor of well-being and happiness (Phillips 1967; Wallace and Pichler 2009; Eurostat 2010). Specifically, it provides people with access to others, networks, jobs and other resources; it helps people gain direct personal rewards such as personal fulfilment through giving to others; and it contributes to self-esteem (Wallace and Pichler 2009). Social participation is important for homeless people because they are often socially isolated (Van Straaten et al. 2016). The obvious reason is that the majority of the homeless population has frequently experienced negative life events, such as a loss of social ties with family and friends, the loss of a job, and their house (e.g., Wolf 2016), and some of the homeless people have even lost their skills to participate in society due to their low physical and mental health conditions (Gadermann et al. 2013), substance misuse (Tam et al. 2003) and aggressive and other behaviours (Fazel et al. 2008). Hence, for homeless people it is a particular challenge to participate in society again. This means that homeless people should have opportunities to interact with others so that they can build new relations, for example through participation in activities as a starting point for social participation (Levasseur et al. 2010).

Most previous research on the social participation of homeless people has focused on housing programmes. Although some authors have demonstrated that housing enhances the social integration of homeless people (Gulcur et al. 2007; Barendregt et al. 2017), others have concluded that this relationship does not exist (Tsai et al. 2012). One study even found a negative association between housing programs and social participation (Chang et al. 2015). Furthermore, an undesirable side-effect of housing interventions can be loneliness (Busch-Geersema 2013) as a result of a lack of social participation. Given the inconsistent findings on the influence of housing programs on social participation and the undesirable side-effect of loneliness, it is clear that social participation by homeless people cannot be achieved by providing housing only. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the role of other predictors of social participation in order to be able to develop rehabilitation and participation-based interventions for homeless people. Housing can be one of the aspects of such an intervention, but in our opinion other factors can also enhance social participation and well-being among homeless people. Consequently, in the current study we explored determinants of well-being among clients of an organisation providing shelter services and ambulatory care (i.e., shelter facility), and we included social participation as a relevant factor.

1.1 Predictors of Social Participation and Well-Being

Social participation of homeless people can be influenced by several factors, such as care-related, demographic-related, and society- or community-related variables. The latter refers to the role of others instead of the role of the homeless person himself or the role of the shelter facility from which he receives support. For example, the social network of homeless people and even the community members play a crucial role in accepting homeless individuals as full citizens, in facilitating them to participate in activities or networks, and to accept them as a part of their own network. Additionally, the government needs to facilitate a structure in which homeless individuals can find their way in the system like every other person. Hence, homeless people have the right to have access to economic, social and cultural institutions. However, the social justice system is often not accessible for homeless people, due to various reasons, for example because of practical issues, such as a lack of a postal address and a lack of financial resources, and issues related to stigmatisation of homeless people (Van Der Maesen and Walker 2005; Amado et al. 2013; Wolf 2016).

Although it is very interesting to examine society-related predictors of social participation of homeless people, the current study focused only on care-related and demographic predictors, because we aimed to examine social participation from the (formerly) homeless individual’s perspective. By gaining deeper insights in care-related and demographic predictors of social participation and its relation to well-being, we aimed to contribute to implications for interventions for homeless people. Consequently, in the current study, we focused especially on two care-related predictors: (1) clients’ participation in various group activities organised by the shelter facility as a part of the support delivered to (formerly) homeless clients, and (2) clients’ experiences with care. We chose these two predictors because they improve social participation and well-being in homeless people (Peden 1993; Kashner et al. 2002; Randers et al. 2011; Sherry and O’May 2013). Additionally, and in line with previous literature, we included age and education level as demographic predictors of social participation and well-being (Phillips 1967; La Due Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; Wallace and Pichler 2009).

1.1.1 Care-Related Predictors

Several studies have shown that participation in various activities organised by a shelter facility or a health care organisation leads to improved social participation and well-being in homeless people. Peden (1993) has shown that participation in a music programme increases interaction with others, decreases loneliness and isolation, and fosters a sense of well-being. One of the advantages is that the use of music provides the care-worker with an opportunity to create a therapeutic relationship with homeless clients (Peden 1993). Thomas et al. (2011) have demonstrated that participating in an art intervention is a good starting point for social participation. Specifically, participation in the programme helped homeless people to become actively involved and accepted members of the intervention group. In addition, it reduced addictive behaviours of participants and it resulted in improvements in mental health, as participants could do something else instead of consuming alcohol and drugs while simultaneously reclaiming a positive identity through self-discovery. In this process, participants developed a new and positive self-image that enabled them to establish new roles and relationships (Thomas et al. 2011). Participation in a work therapy programme can also lead to a decrease in drug and alcohol related problems, and it can prevent a further loss of physical functioning among homeless people (Kashner et al. 2002). However, Kashner et al. (2002) did not find any effects on psychiatric outcomes. Sports interventions for homeless people and comparable target groups (e.g., people in poverty) have also been reported to achieve positive outcomes such as increased social support, reduced substance abuse and symptoms of mental illness (Sherry and O’May 2013), and improved physical health (Randers et al. 2011). Accordingly, for shelter facilities to facilitate social participation and well-being in homeless people, it is important that they offer their clients various activities related to education, recreation, and labour.

Since social participation is currently a high-priority issue for most European governments (Gros and Roth 2012), the main goal for social workers in shelter facilities is to enhance social participation among their homeless clients. This leads to the question whether satisfaction with the social worker and with the services received is associated with higher levels of social participation. To our knowledge there are no studies on the relationship between experience with care (such as satisfaction about the facility and the social worker) and social participation, or on the relationship between experiences with care and well-being among homeless people. McCabe et al. (2001) conducted a study on satisfaction with care among homeless patients, and one of their findings was that well-being played a role in the evaluation of the satisfaction with health care. However, these authors did not consider well-being as an outcome of satisfaction with care. In their view, care workers should take well-being into account in the treatment to increase satisfaction (McCabe et al. 2001). Regarding the relationship between client satisfaction and outcomes in more clinical settings, it has been found that shared decision-making and having a choice in the treatment are predictors of better clinical outcomes (Lindhiem et al. 2014). This is also consistent with research conducted among addicted patients in community-based drug treatment programmes, which demonstrated that a greater satisfaction was positively related to desired treatment outcomes. In this study satisfaction has been operationalised as satisfaction with the services, the counsellor, and the programme (Hser et al. 2004). This means that experiences with the social worker and the shelter facility should be considered when studying predictors of desired outcomes, such as social participation and well-being.

1.1.2 Demographic Predictors

Demographic variables, such as age and education level, are also determinants of social participation and well-being. For example, La Due Lake and Huckfeldt (1998) found that the level of education is positively related to one particular form of social participation, namely political participation. Phillips (1967) reported a very strong positive relationship between education level and social participation; more than half of the study subjects with college training scored significantly higher on social participation compared to those who had lower education (high school or less). More recent research also shows a positive relationship between education level and participation, especially regarding voluntary work (Wallace and Pichler 2009). The relationship between education level and social participation is probably associated with the following issues. First, the higher level of skills of educated people facilitates social participation (Phillips 1967; La Due Lake and Huckfeldt 1998). Second, higher educated people are more interesting for others because of the prestige that is related to higher education (Phillips 1967). Finally, higher educated people have more opportunities to participate for instance in voluntary work (which in turn increases their social participation) because they have a higher level of socio-economic security (Wallace and Pichler 2009). Education also predicts well-being. For example, Phillips (1967) found that highly educated people report more positive feelings and happiness. Additionally, Wallace and Pichler (2009) have reported a positive correlation between education level and life satisfaction.

Social isolation seems to increase with age. Eurostat (2010) has reported that older people have fewer friends, because friendships break up or friends die, while it is difficult to replace these social contacts. Further, Wallace and Pichler (2009) have shown that older people participate less in certain types of activities such as sport clubs, peace and educational associations, but that they participate more in voluntary associations. However, it remains unclear whether their participation in voluntary associations compensates for the lack of participation in other types of activities. Also, there is no consensus in the literature whether age is correlated with well-being (Diener 2009a). In summary, both age and education level seem to be related to social participation, and education level is also related to well-being. Since all the above-mentioned studies on the relationship between demographics and social participation were conducted among the general population, it remains unclear whether the same mechanisms are valid for (formerly) homeless people.

1.2 The Mediating Role of Social Participation

In the current study we consider social participation as a mediator between care-related and demographic predictors and well-being. However, there are to our knowledge no empirical studies that address the question whether social participation can be viewed as mediating the relationship between care-related and demographic variables (such as experiences with care, participation in activities in the shelter facility, education level and age) and well-being as an outcome. Although we did find evidence for a relationship between these specific predictors and social participation (Phillips 1967; Peden 1993; La Due Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; Kashner et al. 2002; Thomas et al. 2011; Sherry and O’May 2013) and between social participation and well-being (Biswas-Diener and Diener 2006; Wallace and Pichler 2009; Eurostat 2010), these authors do not suggest a specific line of causation between the constructs in a model with social participation as a mediator. Therefore, we derived our reasoning from other studies focused on ageing and on sports participation, without focusing on the homeless population (Marlier et al. 2015; Hirve et al. 2013). The study on ageing showed that social networking (an aspect of social participation) mediates the relation between socio-economic status (including education level) and quality of life (Hirve et al. 2013). Regarding the study on sports participation, a model was tested in which social capital (including social ties) mediates sports participation (a specific form of participation in activities) and mental health (one of the aspects of well-being), whereby education also was considered as a predictor of mental health through social capital (Marlier et al. 2015). Specifically, Marlier et al. (2015) and Hirve et al. (2013) tested their proposed models using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with similar concepts as social participation as mediator.

1.3 The Present Study

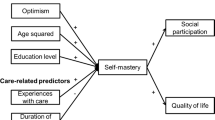

The aim of the present study is to examine care-related and demographic predictors of well-being among clients of a shelter facility in the Netherlands. We tested a mediation model (Fig. 1) in which social participation mediates the relationship between predictors related (1) to care (experiences with care and participation in activities in the shelter facility) and (2) to client demographics (age and education level) on the one hand, and well-being on the other. We expected all relationships between the variables to be positive, except for the age-social participation association (an older age is related to less social participation).

Our study contributes to the literature by emphasizing the mediating role of social participation in the relationship between care-related and demographics predictors on the one hand, and well-being on the other. It is important for shelter facilities to acquire more knowledge and understanding of all these factors, including their interrelatedness. With this knowledge they can develop a rehabilitation programme that promotes social participation with the main goal of enhancing sustainable well-being among homeless people. Moreover, to our knowledge we are the first to include care-related predictors in this model.

2 Method

2.1 Design and Participants

In the Netherlands, it is common practice to define ‘all people who receive support from the shelter facility’ as ‘homeless’ or ‘houseless’ persons even if they are living in their own dwelling and can be categorised as ‘formerly homeless people’ (e.g., Kruize and Bieleman 2014; Planije et al. 2014). The reason for this is that people who have their own dwelling are still at risk of homelessness mostly due to their financial situation and/or their (mental) health condition. For example, research showed that a substantial group, of at least 17–25 % of people relapse in homelessness after they obtained housing (Mayock et al. 2011; Tuynman and Planije 2012; McQuistion et al. 2013; Kostiainen 2015). To deal with this risk, people who have their own dwelling but are still in risk of relapsing in homelessness, can receive support from a shelter facility. In international context, only people who are rooflessness, houselessness (e.g., residential clients of a shelter facility), living in insecure housing or in inadequate housing are considered as ‘homeless’ (Springer 2000; Feantsa 2005). Hence, this definition might include a smaller group as homeless. Therefore, in the current study we used the term ‘(formerly) homeless clients’ which includes residential and ambulatory clients of the shelter facility. Residential clients are persons who live in one of the shelters, and ambulatory clients are persons who live in their own dwelling but have been at serious risk of losing their dwelling or who were homeless in the past.

For our study we used the baseline data (the data that were first available for analyses) from a larger longitudinal study on the effectiveness of a participation-based intervention for homeless people, called ‘Growth Through Participation’ that was conducted among a Dutch shelter facility which provides residential and ambulatory care to homeless adults. The aim of the larger study was to examine whether ‘Growth Through Participation’ is effective at both the client level (e.g., effects in terms of well-being) and the organisational level (e.g., effects on team performance and its predictors).

The data from the baseline measurement used in the present cross-sectional study were collected in the period of March to May 2015 among residential and ambulatory clients. In total 47% (N = 225) of all clients participated in the current study, of which 57% (N = 100) were residential clients and 44% (N = 125) ambulatory clients. The following inclusion criteria were used for the eligible participants: (1) at least 18 years old, (2) understanding Dutch, (3) able to give informed consent; with an additional criterion for residential clients: (4) able to participate in an interview, as residential clients were asked to be interviewed at the location of the shelter facility. Ambulatory clients received a printed version of the questionnaire. The two interviewers, experienced in interviewing clients of health care organisations, were trained in interviewing (formerly) homeless clients and the use and meaning of the questionnaire before the data collection started. Information from both the interviews and the questionnaires was only accessible to the researchers involved in the study. We obtained written informed consent from all participants included in the study and participation was voluntary.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics including gender, age, education level, duration of support by the shelter facility and residential situation were assessed. Duration of support was measured by asking the question: ‘For how long have you been receiving support from this organisation?’ and was categorised as ‘less than one year’ to ‘five years or more’. Education level varied from ‘no education/primary education’ to ‘higher education’. Residential situation was divided into three categories: (1) ‘a residential shelter (short-term stay)’, (2) ‘a residential shelter (long-term stay)’, and (3) ‘living in own dwelling’. A short-term shelter facility is one that provides urgent support to people immediately after they have become homeless with a maximum stay of up to 3 months. A long-term shelter facility offers a more permanent form of accommodation; depending on the needs of the resident, the duration of the stay can last a lifetime.

2.2.2 Care-Related Predictors

Care-related predictors consist of clients’ (1) experiences with care and (2) participation in activities offered by the shelter facility. Experiences with care were assessed using subscales of the Consumer Quality Index for Shelter and Community Care Services (CQI-SCCS) (Beijersbergen and Wolf 2010). Experiences with the services were assessed using nine items of the subscale ‘Services Received’. Satisfaction with the social worker was assessed by means of the four-item subscale ‘Client–Worker Relationship’, and two items concerning ‘General rating’ were used to obtain a general impression of the client satisfaction. Examples of items included ‘Are you getting as much support as you need?’ (Services Received) and ‘Is the social worker (who is supporting you) treating you with respect?’ (Client–Worker Relationship). The items were scored on a four-point Likert scale rating from 1 (never) to 4 (always), with the exception of the items concerning ‘General rating’ which were rated on a scale from 0 to 10. The CQI-SCCS has been used in studies among the homeless before (Lako et al. 2013; Asmoredjo et al. 2016). Participation in activities offered by the shelter facility was measured by gathering information from the registration system about the number of half-day sessions that participants participated in activities (education, recreation, and labour) on a weekly basis. We computed the mean participation rate for a period of four weeks from 2 to 29 March 2015.

2.2.3 Social Participation

As afore mentioned social participation includes two constructs (Levasseur et al. 2010): (1) involvement in activities, and (2) social interactions with others. The first construct was measured using the ‘Participation Ladder’ (Van Gent et al. 2008). This instrument consists of six phases: (1) isolated, (2) social contacts outside of one’s house, (3) participation in organised activities, (4) unpaid work, (5) paid work with additional support, and (6) paid work (Van Gent et al. 2008). We assessed which of the six phases applied for a participant by asking what situation was applicable in his case, for example ‘I have paid work’ or ‘I do not have any social contacts’. Consequently, scoring high on the Participation Ladder means that one is more involved in activities that typically provide social interaction with others in community and society, while scoring low refers to one’s lower level of participation and thus to more isolation. However, a possible comment on this instrument is that work is valued more than participation in organised activities. Therefore, in additional analysis we used a 3 point scale in which several types of work (phase 4, 5, and 6) were scored at the same level as participation in organised activities (phase 3). To our knowledge there is no other study in which the Participation Ladder is used among homeless people. Nevertheless, we used this instrument, because it has been frequently used within the context the shelter facility during the period of the data collection for the current study and it has been recognised by several financers of shelter facilities (Terpstra 2011).

The second construct of social participation, namely social interaction with others refers to one’s interaction with family members, relatives, friends, neighbours, and other acquaintances (Herzog et al. 2002; Levasseur et al. 2010). In order to capture the construct of interactions with others more explicitly, when compared to the Participation Ladder where interaction is rather implicit, we included assessment of social support in the current study. The concept of social support is relevant as it captures not only one’s social interaction with others (Barrera and Ainlay 1983) (e.g., we explicitly asked whether respondents interact with family, friends, and acquaintances), but it assesses also the nature of these interactions. Specifically, it measures to what extent respondents receive for instance emotional and material support from others which is a very relevant when explaining well-being among homeless people (Sherbourne and Stewart 1991). To measure social support, we used five items derived from scales developed for the ‘Medical Outcome Study (MOS) Social Support Survey’ (Sherbourne and Stewart 1991), which has been commonly used in studies among the homeless (Lako et al. 2013; Van Straaten et al. 2016). Participants were asked to specify how often different kinds of support were available to them through (1) family and (2) friends or other acquaintances. Answers could be given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). One example of an item is: ‘How often is your family available to listen to you when you are talking about yourself or your problems?’ (Sherbourne and Stewart 1991). In the current study we calculated the average scores on both subscales separately (family and friends/acquaintances) and transformed scores to a 0–100 scale.

2.2.4 Well-Being

When we use the term ‘well-being’ in the current study, we refer to subjective well-being, as we measure it based on self-reported evaluations. Well-being comprises cognitive and affective aspects (Biswas-Diener and Diener 2006). More specifically, it concerns whether a person feels and thinks his/her life is desirable, pleasant and good (Diener 2009b). A synonymous term would be ‘quality of life’ (Diener 2009b). Mental health and self-esteem are closely related to well-being (Diener and Seligman 2009; Dogan et al. 2013) and thus can be seen as underlying constructs of well-being. Moreover, self-esteem is a good indicator for the affective state of a person (Brown and Marshall 2001). We therefore understand well-being as a combination of quality of life, absence of psychological distress, and self-esteem. Because we could not find any well-being questionnaire that includes these three constructs, we applied three separate instruments to measure each of the constructs.

Quality of life was assessed by the 26-item ‘World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief version’ (WHOQOL-BREF) (WHO 1998; Skevington et al. 2004), consisting of five subscales: ‘Physical Health’, ‘Psychological Health’, ‘Social Relationships’, ‘Environment’ and ‘Overall Quality of Life and General Health’. Example items include: ‘How would you rate your quality of life?’, ‘How much do you enjoy life?’, and ‘How satisfied are you with your personal relationships?’. A five-point Likert scale was used ranging from 1 (very poor or very dissatisfied) to 5 (very good or very satisfied). In the current study we used the total score of the WHOQOL-BREF and transformed this score to a 0–100 scale. The WHOQOL-BREF has been used widely in research among different target groups including homeless people (LePage and Garcia-Rea 2008; Ford et al. 2014). In order to find out whether there is an overlap between the ‘Social Relationships’ items (subscale of WHOQOL-BREF) and the items of the MOS Social Support Survey (part of Social Participation, see Sect. 2.2.3), we explicitly compared these two types of items with each other. Hence, while the items of the WHOQOL-BREF assess satisfaction with the personal relationships (including satisfaction with the received support), the items of the MOS Social Support Survey measure the extent to which people feel supported. Hence, these two types of items do not overlap, because they measure different constructs. Additionally, one item of the WHOQOL-BREF measures the extent to which people have the opportunity for leisure activities. This item may overlap the third phase, namely 'participation in organised activitie's of the Participation Ladder (other aspect of Social Participation). However, the Participation Ladder in general can be considered as a predictor of the opportunity to participate in leisure activities as higher scores on the Participation Ladder (i.e., having a job) expands people’s opportunity to participate in leisure activities, because a job gives people (financial) resources to participate in non-work-related activities (Underlid 1996; Paul and Batinic 2010). Nevertheless, due to possible redundancy between these two items (even if one may argue whether this is the case considering that item of the Participation Ladder is much broader than the item of the WHOQOL-BREF), we conducted an additional analysis where we removed the leisure-activity-item from the WHOQOL-BREF.

Absence of psychological distress was measured using the ‘Brief Symptom Inventory’ (BSI-53) (Derogatis 1975; De Beurs and Zitman 2005). The BSI consists of 53 items and assesses nine patterns of clinically relevant psychological symptoms (dimensions): somatisation, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism. Every item starts with the question ‘During the last week, how much did you experience…’ and examples of items include ‘thoughts of suicide’, ‘feeling lonely’, and ‘having difficulties with making decisions’. A five-point Likert scale was used ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). We reversed the scores so that they measured the absence instead of the presence of psychological distress, and we used the total score of the BSI-53. The BSI has been used widely, also among homeless people (Velasquez et al. 2000; Lako et al. 2013).

Self-esteem was assessed using the ten-item ‘Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale’ (RSES) (Rosenberg 1965; Van Der Linden et al. 1983). Examples of items include ‘On the whole, I am satisfied with myself’, and ‘I certainly feel useless at times’. A four-point Likert scale was used ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). In the current study we transformed scores to a 0–100 scale. The RSES has also been used in several studies among homeless people (Ryan et al. 2000; Lako et al. 2013).

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics and scale reliabilities were analysed using SPSS (version 24), and we used AMOS (version 22) (Arbuckle 2013) for SEM to test the mediation model (Fig. 1). This method enabled us to test the hypothesized model statistically through a simultaneous analysis of all variables and relationships with the aim of determining to what extent the model is consistent with the data (Byrne 2016). It is possible to include both latent and observed variables in the model. Latent variables are variables that are not observed directly, but are operationalised by a combination of observed variables (Byrne 2016). In the current study we distinguished the following latent variables: experiences with care, social participation, and well-being. We conducted Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) for experiences with care and social participation in order to confirm the expected three-factor structure. Unfortunately, we could not perform CFA for well-being because this latent variable is represented by 89 items (WHOQOL-BREF consists of 26 items, BSI of 53 items, and RSES of 10 items) and CFA should be performed for at least 10 respondents per item, which meant that we would need at least 890 participants in our study instead of the current 225 (Schreiber et al. 2006; Blunch 2013). AMOS has been used in several studies in social sciences and other disciplines including studies on well-being and related aspects (Lin and Yeh 2013; Hirve et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013).

Data were screened for missing data before conducting the analyses. Missing value analysis showed that 3% of the data of all variables used in the mediation model were missing. We handled missing data in two steps. First, regarding the WHOQOL and BSI we used the instructions on missing data from the user manuals (Derogatis 1975; WHO 1998). The BSI manual indicates that the total BSI score can be calculated if 12 or fewer items are missing (Derogatis 1975). The WHOQOL manual states that 20% of the items are allowed to be missing for calculation of the total score, which means that five items can have missing scores for each respondent (WHO 1998). We calculated the total scores for both scales, total BSI and total QoL, if at least 41 items (BSI) and 21 items (QOL) were filled in. We could not find such instructions in the manuals of the other questionnaires that we used. Therefore, we only computed mean scores if all items of the (sub)scale were filled in. Second, we used the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) method to obtain estimates of the parameters, which is considered to be one of the best methods to handle missing data as it yields less biased results than the commonly used methods of list-wise or pair-wise deletion (Enders and Bandalos 2001; Arbuckle 2013; Byrne 2016).

The fit of the measurement model was evaluated using a combination of fitness indexes. In the current study we used the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) as a measure for incremental fit, the Root Mean Square of Error of Approximation (RMSEA) as a measure for absolute fit, and the Chi Square/Degrees of Freedom (χ2/df) as a measure for parsimonious fit. A model is considered to have a good fit if CFI > .90, RMSEA < .08, and χ2/df < 3.0 (Awang 2012; Arbuckle 2013).

Finally, we computed the significance of the indirect effects of every (significant) predictor on well-being to determine whether partial or full mediation occurs. The direct effects are the effects that go directly from every predictor to well-being. The indirect effects are the effects that go indirectly from every predictor through the mediator (social participation) to well-being. Mediation occurs when the indirect effects are greater than the direct effects. Partial mediation occurs when the direct effect is still significant after the mediator is included in the model and full mediation occurs when the direct effect is not significant (Awang 2012).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

The demographic characteristics of all participants in the current study are presented in Table 1. Seventy-two percent of the 225 participants is female, the mean age of the participants was 49.3 years, and 56% lived in their own house with ambulatory support. The duration of the support by the shelter facility varied: the largest group of participants (36%) received support from the shelter facility for a period of 2–5 years. The education level also varied, but most participants had intermediate education (36%).

The means of the other variables are presented in Table 2, namely services received (3.15), client–worker relationship (3.47), general rating (7.28), participation in activities in the shelter facility (1.70), participation ladder (3.40), social support (202), quality of life (60.42), self-esteem (29.49), and absence of psychological distress (3.29). Cronbach’s alfas were also calculated and they were all satisfactory, ranging from .81 to .97.

3.2 The Structural Equation Model

The results from the Confirmative Factor Analyses (CFA’s) confirmed the three-factor structure for both experience with care and social participation variables. The CFA model for experiences with care had a reasonable fit: χ2/df was 2.535, CFI was .933, and RMSEA was .083. The CFA model for social participation had a good fit: χ2/df was 2.369, CFI was .973, and RMSEA was .078. All the factor loadings were significant (p < .001) in both models. We could not perform CFA for well-being because this latent variable was represented by 89 items and our sample size was not large enough to conduct this analysis (Schreiber et al. 2006; Blunch 2013). However, in the current path models (Figs. 2, 3) the indicators of well-being (quality of life, absence of psychological distress, and self-esteem) were all significantly related to the latent variable of well-being, which implies that the latent variable was represented by these three indicators.

Structural Equation Model for well-being, social participation, and predictors (N = 225). Standardized regression coefficients are shown next to the arrows, and factor loadings are printed in italics. Proportions of variance explained are reported below construct names. Ovals represent latent variables and rectangles represent observed variables. *p < .05.; **p < .01.; ***p < .001. n.s.p = non-significant. $Loading fixed at the value of 1 in the non-standardized solution

Final Structural Equation Model for well-being and predictors (N = 225). Standardized regression coefficients are shown next to the arrows, and factor loadings are printed in italics. Proportions of variance explained are reported below construct names. Ovals represent latent variables and rectangles represent observed variables. *p < .05.; **p < .01.; ***p < .001. $Loading fixed at the value of 1 in the non-standardized solution

First, we tested the hypothesized model without social participation as mediator, which had a good fit: χ2/df was 1.018, CFI was .999, and RMSEA was .009. In this model, experiences with care, participation in activities in the shelter facility and education level were significantly related to well-being while a non-significant relationship was found between age and well-being. Only 15% of the variance of well-being was explained by its predictors. Second, we tested the hypothesized mediation model with social participation as a mediator (Fig. 2), which also had a good fit: χ2/df was 1.858; CFI was .942, and RMSEA was .062. We found support for a model in which social participation mediates the relationship between experiences with care and education level, and with well-being. However, participation in activities in the shelter facility and age were not significantly related to well-being through social participation. The proportion variance explained for well-being was 38% and for social participation 27% in this model.

Third, we tested whether social participation is a partial or full mediator. The indirect effect of experiences with care on well-being was .254, and the direct effect was .013. Since the indirect effect was greater than the direct effect, while the direct effect is not significant when the mediator is included in the model, full mediation occured. Regarding education level, the indirect effect (.113) was greater than the direct effect (.070) and the direct effect was not significant after the mediator enters the model, hence social participation could also be considered a full mediator here.

Finally, we tested a model in which participation in activities in the shelter facility is directly related to well-being and in which age is excluded (Fig. 3). We linked participation in activities in the shelter facility directly with well-being, because the first model (without mediator) showed that participation in activities in the shelter facility was directly and significantly correlated with well-being, whereas the second model (Fig. 2) showed that it was not significantly correlated with social participation. Further, we excluded age because it was not significantly related to social participation or to well-being in the first and second model. Consequently, we considered social participation as a full mediator between only two predictors, namely experiences with care and education level, and well-being. The model (Fig. 3) had a good fit; χ2/df was 1.668, CFI was .961, and RMSEA was .055. Participation in activities in the shelter facility was significantly related to well-being in this model. All relations were significant. The proportion variance explained for well-being was 45% and for social participation 27% in this final model.

As stated in Sect. 2.2 we conducted two additional analyses. In the first analysis we used a 3 point scale regarding the Participation Ladder. By using this adapted scale we valued work on the same level as organised activities. We tested whether the relationships in the SEM model (Fig. 3) changed. All relationships remained significant and the model still had a good fit (χ2/df was 1.766, CFI was .955, and RMSEA was .058). In the second analysis, we excluded the item regarding the extent to which people have the opportunity for leisure activities from the total quality of life score. Hence, the mean score of WHOQOL BREF changed slightly from 60.42 (SD = 16.32) to 61.38 (SD = 16.32). All relationships remained significant and the model fit remained exactly the same as the SEM model presented in Fig. 3 (χ2/df was 1.668, CFI was .961, and RMSEA was .055). Conclusively, deleting the leisure-item from the total Quality of life scale would not make a significant difference.

4 Discussion

The present study examined predictors of well-being through social participation in (formerly) homeless clients of a Dutch shelter facility. We found that the clients’ experiences with care and education level are predictors of well-being through social participation and that participation in activities in the safe environment of the shelter facility is a direct predictor of well-being. Age was not significantly related to social participation or well-being. These findings are partially in line with our hypothesized model.

First, as expected, we confirmed that social participation is a mediator between experiences with care and well-being. Social participation is one of the primary goals pursued by shelter facilities, as it provides various benefits. Our research indicates that a higher satisfaction about (1) the services received, (2) client–worker relationship, and (3) the general satisfaction with the support can lead to a higher level of social participation by clients of the shelter facility. Second, and in line with our expectations, education level was found to be related to well-being through the mediator of social participation. Higher educated clients receive more social support from family, friends and other acquaintances and score higher on the Participation Ladder, which implies that they are less socially isolated. Also, they more often have a job than lower educated clients. Additionally, our data confirmed earlier research (Biswas-Diener and Diener 2006; Wallace and Pichler 2009; Eurostat 2010; Van Straaten et al. 2016) that higher levels of social participation lead to an enhancement of well-being, which we operationalized as a better quality of life, less psychological distress and improved self-esteem. Third, and not in line with our hypothesized model, participation in activities at the shelter facility has a direct influence on well-being, rather than an indirect influence. In the introduction we noted that participation in group activities has several benefits, both for well-being and for social relationships (which is one dimension of social participation) (Peden 1993; Kashner et al. 2002; Randers et al. 2011; Thomas et al. 2011; Sherry and O’May 2013). A possible explanation for not finding a relationship between participation in group activities and social participation may be the low levels of participation in the shelter facility: about half of the participants in the current sample did not participate in activities, and therefore the average participation rate was low (only 1.7 half-day sessions per week). If the participation level could be increased, it is highly probable that this would have a stronger impact on social participation and even on well-being. Another possible explanation might be that the activities are not focusing enough on social participation, including building relationships with friends and family. In the current study we did not evaluate the quality and the content of the activities, which means that we cannot draw a conclusion on this. However, in another qualitative study that was conducted in the same shelter facility we found that participation in activities in the shelter improved social support, clients made new friends, developed stronger communication skills, and became more social and helpful (Rutenfrans-Stupar et al. 2019). Finally, we could not confirm the relationship between age and social participation (i.e., we expected that the older the clients are, the lower their social participation rate would be). It might be that at a higher age, homeless individuals are more involved in social participation programmes provided by shelter facilities as they are the most vulnerable group (compared to the younger homeless). Through participation in these programmes, they may experience higher levels of social support.

Our findings suggest that shelter facilities can influence social participation and well-being by working on several factors. The finding that clients’ experiences with care are related to social participation and well-being, leads to the advice that it is important to enhance client satisfaction, under which the clients’ experiences with the client–worker relationship. This can be fostered by building a client–worker relationship in which the homeless client is treated with respect and his/her autonomy is enlarged. Clients should be provided with valid information at the right moment, and the support should be given in time. Clients should also be stimulated to take decisions on their own. This is in line with previous findings by Lindhiem et al. (2014), who already emphasized the importance of the decision-making process in health care. Hence, social workers should build a therapeutic alliance that can be described as ‘the collaborative and affective bond between therapist and patient’ (Martin et al. 2000, p. 438) or, in our case, ‘the collaborative and affective bond between social worker and homeless client’. A therapeutic alliance can help clients cope with different situations and to regulate their emotions; it ensures that clients are involved in the decision-making process (Lindhiem et al. 2014); and it is related to positive outcomes (Martin et al. 2000). A therapeutic alliance is especially important for homeless people, as they often have lost trust in others and have lost social contacts. Therefore, homeless people need to connect to an ‘anchor’, which can initially be found in an intensive therapeutic relationship with the social worker (Van Regenmortel et al. 2006). Accordingly, our recommendation is to train social workers on the principles of therapeutic alliance which can be promoted by applying one of the contemporary strength- and rehabilitation-based approaches that are already used widely by social workers at shelter facilities in the Netherlands (e.g., Den Hollander and Wilken 2013; Wolf 2016).

The finding that participation in activities in the shelter facility enhances well-being, leads to the advice that shelter facilities should offer clients an activity programme that consists of educational, recreational and work activities in a safe environment where they are not stigmatized and are stimulated to work on self-development and to connect to other people. Such an environment is also called an ‘enabling niche’ in the literature, because it enables clients to learn how to interact with others, to improve their self-esteem, and to take responsibility (Taylor 1997; Driessens and Van Regenmortel 2006). Other research supports our findings that in addition to individual mentoring, group interventions can promote beneficial outcomes. For example, other researchers found that a group intensive peer support intervention is an effective substitute for individual case management. Homeless clients experienced positive outcomes, especially in regard to self-reported social integration (Tsai and Rosenheck 2012). However, a negative side effect of offering activities in a safe environment can be that it raises the threshold to participating in society; this is the well-known effect of institutionalisation (Goffman 1961), in other words the ‘enabling niche’ can become an ‘entrapping niche’. We assume that there is a very thin dividing line between an enabling niche and an entrapping niche, but with the right precautions institutionalisation can be prevented. Therefore, social workers should take care to create an environment (i.e., an ‘enabling niche’) in which clients have access to others and are enabled to reach a better position, in which they are stimulated and enabled to move on to other niches, and in which they interact with other people than only homeless people. They should also be incentivised to set realistic long-term goals (Taylor 1997; Driessens and Van Regenmortel 2006). The Participation Ladder used in this study (or a comparable instrument) can give (formerly) homeless clients more insight into their own situation and can help them set, pursue and reach personal goals. However, in the current study we did not examine the extent to which institutionalisation took place: future research is needed to examine whether the activities the shelter facility offered during the current study meets the criteria of the ‘enabling niche’.

Finally, our research underlines the need for education among (formerly) homeless people. As obtaining higher education qualifications at an older age is not always possible, we call for the solid education of children of homeless people and other vulnerable children. These children are at risk of not receiving proper education, which can cause poverty in the long term as well as various other problems (Zima et al. 1997). This can put them at risk of becoming homeless at an older age. Research shows that access to school is not a problem for homeless children, but their school achievements are lower compared to children of non-homeless parents (Masten et al. 1997). Per year in the Netherlands, there are approximately 7000 children of parents who live in a shelter facility (Van Rijn 2017). The parents mostly receive psychological help for their problems, but the children do not always receive the attention they need (VanMontfoort 2017). Therefore, special attention should be given to vulnerable children, certainly with respect to their future perspectives, which clearly includes education.

The current study has some limitations. First, it was conducted in the context of a Dutch shelter facility, which might limit its external validity. Second, Structural Equation Modelling tests whether relations exist, but it cannot test the causality between variables. Third, our data relies on self-reports by clients of the shelter facility. Fourth, one of the instruments we used, namely the Participation Ladder, has not yet been scientifically validated. Fifth, other variables such as material deprivation, the presence of debts and (lack of) access to social rights could also be predictors of social participation (Van Straaten et al. 2016). Finally, institutions and civil society also play a fundamental role in realizing social participation for homeless people, because social participation is a task for society as a whole. Hence, the model we tested is a simplification of reality and does not take all predictors and perspectives on social participation into account. Accordingly, future research would benefit from a longitudinal or experimental approach in which causality is examined from a different and perhaps more objective point of view, including the opinion of the social workers, government workers, citizens, and, if present, the client’s own social network, and whereby societal and political aspects are also included.

In conclusion, interventions for homeless people should be based on a combination of individual and group approaches. Unfortunately, some Dutch (mental) health care institutions have been implementing cost-cutting measures recently, and have stopped offering activity programmes to clients. However, we believe that group-based interventions can actually help to save costs, especially when parts of the individual programmes are substituted by group work. Health care organisations should look for possibilities to finance group interventions and financers of health care organisations should take a positive approach to these evidence-based methods, given their beneficial outcomes. Clearly, more research regarding the cost-effectiveness of activity-based programmes would be helpful.

References

Amado, A. N., Stancliffe, R. J., McCarron, M., & McCallion, P. (2013). Social inclusion and community participation of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(5), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.5.360.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2013). IBM SPSS Amos 22 user’s guide. New York: IBM.

Asmoredjo, J., Beijersbergen, M. D., & Wolf, J. R. L. M. (2016). Client experiences with shelter and community care services in the Netherlands. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(7), 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516637426.

Awang, Z. H. (2012). A handbook on SEM. Shah Alam: UiTM.

Barendregt, C., Wewerinke, D., Rodenburg, G., Boersma, S., Van Straaten, B., Wolf, J., et al. (2017). Dakloze en ex-dakloze mensen over erbij horen en meedoen, 2,5 jaar na hun instroom in de maatschappelijke opvang. Rotterdam/Nijmegen: IVO/Impuls.

Barrera, M., & Ainlay, S. L. (1983). The structure of social support: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Journal of Community Psychology, 11(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198304)11:2%3c133.

Beijersbergen, M. D., & Wolf, J. R. L. M. (2010). De CQ-index voor de maatschappelijke opvang, vrouwenopvang en zwerfjongerenopvang: Ontwikkeling van een meetinstrument voor cliëntervaringen met de opvang. Nijmegen: UMC St Radboud.

Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2006). The subjective well-being of the homeless, and lessons for happiness. Social Indicators Research, 76(2), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-8671-9.

Blunch, N. J. (2013). Introduction to structural equation modeling using IBM SPSS statistics and Amos. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Brown, J. D., & Marshall, M. A. (2001). Self-esteem and emotion: Some thoughts about feelings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(5), 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201275006.

Busch-Geersema, V. (2013). Housing first Europe: Final report. http://www.habitat.hu/files/FinalReportHousingFirstEurope.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 2017.

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with Amos. New York: Routledge.

Chang, F.-H., Helfrich, C., Coster, W., & Rogers, E. (2015). Factors associated with community participation among individuals who have experienced homelessness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(9), 11364–11378. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911364.

De Beurs, E., & Zitman, F. G. (2005). De Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): De betrouwbaarheid en validiteit van een handzaam alternatief voor de SCL-90. Maandblad Geestelijke Volksgezondheid, 61, 120–141.

Den Hollander, D., & Wilken, J. P. (2013). Zo worden cliënten burgers: Praktijkboek Systematisch Rehabilitatiegericht Handelen. Amsterdam: SWP.

Derogatis, L. R. (1975). The brief symptom inventory. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research.

Diener, E. (2009a). Subjective well-being. In E. Diener (Ed.), The science of well-being (pp. 1–10). Dordrecht: Springer.

Diener, E. (2009b). The science of well-being: Reviews and theoretical articles by Ed Diener. In E. Diener (Ed.), The science of well-being (pp. 1–10). Dordrecht: Springer.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. In E. Diener (Ed.), The science of well-being (pp. 1–10). Dordrecht: Springer.

Dogan, T., Totan, T., & Sapmaz, F. (2013). The role of self-esteem, psychological well-being, emotional self-efficacy, and affect balance on happiness: A path model. European Scientific Journal, 9(20), 31–42.

Driessens, K., & Van Regenmortel, T. (2006). Bind-kracht in armoede: Leefwereld en hulpverlening. Leuven: Lannoo Campus.

Enders, C., & Bandalos, D. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem0803_5.

Eurostat. (2010). Social participation and social isolation. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-working-papers/-/KS-RA-10-014. Accessed 1 Dec 2017.

Fazel, S., Khosla, V., Doll, H., & Geddes, J. (2008). The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Medicine, 5(12), 1670–1681.

Feantsa. (2005). ETHOS: European typology on homelessness and housing exclusion. https://www.feantsa.org/en/toolkit/2005/04/01/ethos-typology-on-homelessness-and-housing-exclusion. Accessed 1 Dec 2017.

Ford, P., Cramb, S., & Farah, C. (2014). Oral health impacts and quality of life in an urban homeless population. Australian Dental Journal, 59(2), 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12167.

Gadermann, A. M., Hubley, A. M., Russell, L. B., & Palepu, A. (2013). Subjective health-related quality of life in homeless and vulnerably housed individuals and its relationship with self-reported physical and mental health status. Social Indicators Research, 116(2), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0302-2.

Goffman, E. (1961). Assylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. New York: Anchor Books.

Gros, D., & Roth, F. (2012). The Europe 2020 strategy. Can it maintain the EU’s competitiveness in the world? https://www.ceps.eu/publications/europe-2020-strategy-can-it-maintain-eu%E2%80%99s-competitiveness-world. Accessed 1 Dec 2017.

Gulcur, L., Tsemberis, S., Stefancic, A., & Greenwood, R. M. (2007). Community integration of adults with psychiatric disabilities and histories of homelessness. Community Mental Health Journal, 43(3), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-006-9073-4.

Herzog, A. R., Ofstedal, M. B., & Wheeler, L. M. (2002). Social engagement and its relationship to health. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 18(3), 593–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00025-3.

Hirve, S., Oud, J. H. L., Sambhudas, S., Juvekar, S., Blomstedt, Y., Tollman, S., et al. (2013). Unpacking self-rated health and quality of life in older adults and elderly in India: A structural equation modelling approach. Social Indicators Research, 117(1), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0334-7.

Hser, Y.-I., Evans, E., Huang, D., & Anglin, D. M. (2004). Relationship between drug treatment services, retention, and outcomes. Psychiatric Services, 55(7), 767–774. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.767.

Kashner, T. M., Rosenheck, J. D., Campinell, A. B., Suris, A., et al. (2002). Impact of work therapy on health status among homeless, substance-dependent veterans. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(10), 938. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.938.

Kostiainen, E. (2015). Pathways through homelessness in Helsinki. European Journal of Homelessness, 9(2), 63–86.

Kruize, A., & Bieleman, B. (2014). Monitor dakloosheid en chronische verslavingsproblematiek. Groningen: Intraval.

La Due Lake, R., & Huckfeldt, R. (1998). Social capital, social networks, and political participation. Political Psychology, 19(3), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895x.00118.

Lako, D. A., de Vet, R., Beijersbergen, M. D., Herman, D. B., van Hemert, A. M., & Wolf, J. R. (2013). The effectiveness of critical time intervention for abused women and homeless people leaving Dutch shelters: Study protocol of two randomised controlled trials. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-555.

LePage, J. P., & Garcia-Rea, E. A. (2008). The association between healthy lifestyle behaviors and relapse rates in a homeless veteran population. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 34(2), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990701877060.

Levasseur, M., Richard, L., Gauvin, L., & Raymond, É. (2010). Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: Proposed taxonomy of social activities. Social Science and Medicine, 71(12), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.041.

Lin, C.-C., & Yeh, Y. (2013). How gratitude influences well-being: A structural equation modeling approach. Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0424-6.

Lindhiem, O., Bennett, C. B., Trentacosta, C. J., & McLear, C. (2014). Client preferences affect treatment satisfaction, completion, and clinical outcome: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(6), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.002.

Marlier, M., Van Dyck, D., Cardon, G., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Babiak, K., & Willem, A. (2015). Interrelation of sport participation, physical activity, social capital and mental health in disadvantaged communities: A SEM-analysis. PLoS ONE, 10(10), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140196.

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.68.3.438.

Masten, A. S., Sesma, A., Si-Asar, R., Lawrence, C., Miliotis, D., & Dionne, J. A. (1997). Educational risks for children experiencing homelessness. Journal of School Psychology, 35(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-4405(96)00032-5.

Mayock, P., O’Sullivan, E., & Corr, M. L. (2011). Young people exiting homelessness: An exploration of process, meaning and definition. Housing Studies, 26(6), 803–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2011.593131.

McCabe, S., Macnee, C. L., & Anderson, M. K. (2001). Homeless patients’ experience of satisfaction with care. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 15(2), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1053/apnu.2001.22407.

McQuistion, H. L., Gorroochurn, P., Hsu, E., & Caton, C. L. M. (2013). Risk factors associated with recurrent homelessness after a first homeless episode. Community Mental Health Journal, 50(5), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-013-9608-4.

Paul, K. I., & Batinic, B. (2010). The need for work: Jahoda’s latent functions of employment in a representative sample of the German population. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.622.

Peden, A. R. (1993). Music: Making the connection with persons who are homeless. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 31(7), 17–20.

Phillips, D. L. (1967). Social participation and happiness. American Journal of Sociology, 72(5), 479–488.

Planije, M., Tuynman, M., & Hulsbosch, L. (2014). Monitor plan van aanpak maatschappelijke opvang: Rapportage 2013/’14. Utrecht: Trimbos Instituut.

Randers, M. B., Petersen, J., Andersen, L. J., Krustrup, B. R., Hornstrup, T., Nielsen, J. J., et al. (2011). Short-term street soccer improves fitness and cardiovascular health status of homeless men. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 112(6), 2097–2106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-2171-1.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rutenfrans-Stupar, M., Van Der Plas, B., Den Haan, R., Van Regenmortel, T., & Schalk, R. (2019). How is participation related to well-being of homeless people? An explorative qualitative study in a Dutch homeless shelter facility. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 28, 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2018.1563267.

Ryan, K. D., Kilmer, R. P., Cauce, A. M., Watanabe, H., & Hoyt, D. R. (2000). Psychological consequences of child maltreatment in homeless adolescents: Untangling the unique effects of maltreatment and family environment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24(3), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00156-8.

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/joer.99.6.323-338.

Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b.

Sherry, E., & O’May, F. (2013). Exploring the impact of sport participation in the Homeless World Cup on individuals with substance abuse or mental health disorders. Journal of Sport for Development, 1(2), 1–11.

Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M., & O’Connell, K. A. (2004). The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. Quality of Life Research, 13, 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:qure.0000018486.91360.00.

Springer, S. (2000). Homelessness: A proposal for a global definition and classification. Habitat International, 24(4), 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-3975(00)00010-2.

Tam, T. W., Zlotnick, C., & Robertson, M. J. (2003). Longitudinal perspective: Adverse childhood events, substance use, and labor force participation among homeless adults. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 29(4), 829–846.

Taylor, J. B. (1997). Niches and practice: Extending the ecological perspective. In D. Saleebey (Ed.), The strengths perspective in social work practice (pp. 217–227). New York: Longman.

Terpstra, A. (2011). Implementatie en gebruik Participatieladder: Een inventarisatie naar de stand van zaken bij 24 gemeenten en ISD-en. Den Haag: VNG.

Thomas, Y., Gray, M., McGinty, S., & Ebringer, S. (2011). Homeless adults engagement in art: First steps towards identity, recovery and social inclusion. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58(6), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00977.x.

Tsai, J., Mares, A. S., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2012). Does housing chronically homeless adults lead to social integration? Psychiatric Services, 63(5), 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100047.

Tsai, J., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2012). Outcomes of a group intensive peer-support model of case management for supported housing. Psychiatric Services, 63(12), 1186–1194. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200100.

Tuynman, M., & Planije, M. (2012). Monitor plan van aanpak maatschappelijk opvang: Rapportage 2011. Utrecht: Trimbos Instituut.

Underlid, K. (1996). Activity during unemployment and mental health. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 37(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.1996.tb00659.x.

Van Der Linden, F. J., Dijkman, T. A., & Roeders, P. J. B. (1983). Metingen van kenmerken van het persoonssysteem en sociale systeem. Nijmegen: Hoogveld instituut.

Van Der Maesen, L. J. G., & Walker, A. C. (2005). Indicators of social quality. European Journal of Social Quality, 5(1–2), 00. https://doi.org/10.3167/146179105780337431.

Van Gent, M. J., Van Horssen, C., Mallee, L., & Slotboom, S. (2008). De participatieladder: Meetlat voor het participatiebudget. Amsterdam: Regioplan.

Van Regenmortel, T., Demeyer, B., Vandenbempt, K., & Van Damme, B. (2006). Zonder (t)huis. Sociale biografieën van thuislozen getoetst aan de institutionele en maatschappelijke realiteit. Leuven: Lanno Campus.

Van Rijn, M. J. (2017). Commissiebrief Tweede Kamer inzake aangeboden petitie Het vergeten kind en the unforgettables m.b.t. kinderen in maatschappelijke- en vrouwenopvang. Den Haag: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport.

Van Straaten, B., Rodenburg, G., Van der Laan, J., Boersma, S. N., Wolf, J. R. L. M., & Van de Mheen, D. (2016). Changes in social exclusion indicators and psychological distress among homeless people over a 2.5-year period. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1486-z.

VanMontfoort. (2017). Ben ik in beeld?. Woerden: VanMontfoort.

Velasquez, M. M., Crouch, C., Von Sternberg, K., & Grosdanis, I. (2000). Motivation for change and psychological distress in homeless substance abusers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 19(4), 395–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00133-1.

Wallace, C., & Pichler, F. (2009). More participation, happier society? A comparative study of civil society and the quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 93(2), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9305-9.

WHO. (1998). WHOQOL user manual. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wolf, J. (2016). Krachtwerk. Methodisch werken aan participatie en zelfregie. Bussum: Coutinho.

Zhang, J., Miao, D., Sun, Y., Xiao, R., Ren, L., Xiao, W., et al. (2013). The impacts of attributional styles and dispositional optimism on subject well-being: A structural equation modelling analysis. Social Indicators Research, 119(2), 757–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0520-7.

Zima, B. T., Bussing, R., Forness, S. R., & Benjamin, B. (1997). Sheltered homeless children: Their eligibility and unmet need for special education evaluations. American Journal of Public Health, 87(2), 236–240. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.87.2.236.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dilek Kocabiyik and Marieke Pepers for their help with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The first author of the paper is employed by SMO Breda, the shelter facility where the research is conducted. However, the management board of SMO Breda had no role in the study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor in the content of the paper. Furthermore, the conditions of the employment of this author are fully independent of the content and publication of the current paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rutenfrans-Stupar, M., Van Regenmortel, T. & Schalk, R. How to Enhance Social Participation and Well-Being in (Formerly) Homeless Clients: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Soc Indic Res 145, 329–348 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02099-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02099-8