Abstract

On the basis of a newly built regional panel data set that considers both the evolution of employment indicators in the Italian regions and indicators of counterfeiting activities and criminality, we empirically explore the link between joblessness and criminality. During the period of a deep economic and financial crisis we observed that, unexpectedly, unemployment and inactivity rates rise together. The paper studies whether and to what extent, in the considered period, criminal activities of counterfeit and other forms of crime have affected unemployment and inactivity rate. We present results of GMM regressions showing a positive/peculiar effect of criminal activities on both the components of joblessness.

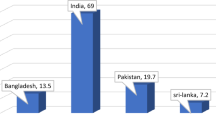

Source: OECD.stat

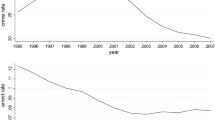

Source: Elaboration on data provided by Italian Ministry of Justice and from the IPERICO data set

Source: Elaboration on data provided by the Italian National Statistical Institute (ISTAT)

Source: Our elaboration on data provided by Italian Ministry of Justice

Source: Our elaboration on data from the IPERICO data set

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The contemporaneous increase in both inactivity and unemployment has been documented in ISTAT (2011a, b). ISTAT (2011b) shows that the increase in the inactivity rate, was particularly pronounced in the southern Italian regions, characterised by a drop in the participation rate. There a so called “discouragement effect” likely played an important role and was considered a reason, among others, of the expansion of the inactivity rate during the crisis. The latter, in turn, might have determined, per se, the relatively restrained increase of the Italian unemployment as compared to other developed economies (see ISTAT 2011b).

In this respect, it is important to notice that the data related to both the number of seizures and the number of the seized pieces represent the universe of observations, whereas the value of the seized goods is estimated according to a methodology elaborated by the General Direction of the Ministry of Economic Development for the contrast activity against counterfeiting. Such estimates are based on the value assigned to the seized goods by the Custom Agency, according to both the quality of the goods and the differences between the expected counterfeited sale price and the market price of the original good.

This view has undergone some criticisms (Baker et al. 2005; Amable and Gatti 2006; Freeman 2005). Empirical results provided in those contributions indicate that the relationship between institutional arrangements and employment performance is indeed more complex than the policy recommendations seemed to imply. Moreover, a few theoretical papers have argued that removing rigidities and implementing flexible labour markets may indeed be quite complicate because the various imperfections are complementary to each other (Coe and Snower 1997; Orszag and Snower 1999).

Amable et al. (2007), Blanchard and Giavazzi (2003), Koeniger and Vindigni (2003) and Koeniger and Prat (2007) consider the existence of interactions between product and labour markets institutions; Wasmer and Weil (2004) and Acemoglu (2001) consider the interactions between labour and financial markets imperfections. Some of these studies point out that deregulation may yield perverse effects on employment (Amable and Gatti 2004), but only few empirical work—e.g., Boeri et al. (2000b), Haffner et al. (2000) and Nicoletti and Scarpetta (2002)—try to account for these interdependencies.

Both these works—in line with Boeri et al. (2000a), who provide policy recommendation to avoid long-term unemployment—suggest to operate the decentralisation of the wage setting at a regional level, so that wages can adjust when responding to shocks.

The relation between economic recession and unemployment has been tackled also from a different perspective known as “added worker effect”, a phenomenon that occurs when married women, if behaving as secondary workers, increase women’s labour supply when their husbands become unemployed. This is exactly the opposite of what we observe from the data in the current economic crisis, for which ISTAT reports an increase of women’s inactivity rate never observed before. Ghignoni and Verashchagina (2016) shows that the Italian female’s labour supply barely reacts to a reduction in male’s earnings during the crisis in the direction expected unless a joint reduction in earnings and hours worked apply.

They highlight the fact that the size of the informal sector in European countries is affected by a large variance, which range from the 10–12% of the GDP in the Nordics, to figure from 20 to 30% of the GDP in the Southern Europe and Ireland. Moreover, they suggest also the existence of a significant within-country variation: the shadow economy (and so the shadow employment) is higher in depressed regions, such as the South of Italy that is also characterised by low productivity. As for Italy, Calzaroni and Pascarella (1998) suggest that the proportion of irregular employment fluctuates from a 30–35% in the South of Italy to less than 10% in the North, while the Centre seems to be collocated in between (about 20%).

In this respect, Daniele and Marani (2012) find a significant negative relation between organized crime and foreign direct investments flows: if the “regular” economic activities are strongly discouraged in those areas affected by a strong presence of organized crime, these same areas are likely to be those where the expansion of shadow employment is stronger.

In the same strand of literature, Becker (1968) and Edmark (2005) examine the effect of unemployment on criminality, whereas Chang and Wu (2012) investigate the effect of crime on unemployment. In particular, Chang and Wu (2012) find that an increase in the average crime rate in the economy leads to a decrease in the employment rate due to a reduction in the number of vacancies offered by firms.

The authors refer to the definition of “shadow sector” provided by the System of National Account 1993, which defines it as the set of legal activity unknown to the public administration because of tax evasion, unwillingness to pay social contributions, non-application of contractual wage minima of hours of work and health at work standard.

Boeri and Garibaldi (2002) found empirical evidence that unemployment and shadow employment share similar properties. A drop of unemployment has the effect to reduce the shadow employment, while policies aimed to contrast the illegal employment without tackling the structural unemployment seem to increase unemployment. A possible explanation is that a rise in “contrast activity” against shadow employment could require a tax increase to finance the increasing cost of the contrast activity itself. This determines a similar variation in unemployment, followed by an increase of shadow employment. Moreover, since people working in the shadow sector are not generally unemployed—resulting instead inactive workers—they could start looking for a regular job, once the illegal job is lost, thus becoming unemployed in the national statistics.

As for the effect of criminal activities, in particular of organized crime on employment, some scholars have shown the existence of a positive and significant impact of the mafia pressure in the employment dynamics. In this sense, Scognamiglio (2015) performed an empirical analysis aimed to evaluate the effect of mafia-type criminal organizations on the employment in different sectors. In particular, the author uses a law (which was in force in Italy between 1956 and 1988 and forced the mafia members to resettle to another town) as a proxy for the arrival of illegal capitals in a new area. She assumed that the higher the number of resettlement in a given province, the higher the probability to create criminal connections in the destination province. By looking at eight employment sectors, she shows that the resettlement of mafiosos had a positive and robust impact on the employment mainly in the construction sector, which better allows the criminal organizations to invest in new localities for money laundering purposes.

The ISCED belongs to the United Nations International Family of Economic and Social Classifications, which are applied in statistics worldwide with the purpose of assembling, compiling and analysing cross-nationally comparable data. It is the reference classification for organizing education programmes and related qualifications by education levels and fields (UNESCO 2011).

Overman and Puga (2002), for example, argue that regional unemployment outcomes might reflect a different skill composition of labor forces: regions, with lower skilled workers likely to experience higher unemployment levels and vice versa.

This is due to a ‘hysteresis effect’ that may be produced when, owing to a long period of unemployment, human capital diminishes and, more generally, the professional abilities decline to the point that prevents people from being hired again. This effect may be accentuated by the introduction during the crisis of excessively generous benefits and other forms of unemployment support that discourage the supply of labour (IMF 2009, Chapter 4; OECD 2009, Chapter 1 and the literature quoted therein).

For each variable, we have taken the ratio between the annual national average and the sum of the mean of all the considered years. In particular, here we use the average dimension of seizures aggregated at a national level.

In this case, for each region and for each variable, we have used the ratio between the average value in the considered period and the sum of the regional mean in the same years.

We choose not to set the counterfeiting variable as endogenous because, as observed in Sect. 3, its spatial distribution is quite different from those of OC and PC, which, for example, assume the highest values in those same regions with high UR and IR. For this reason, the presence of simultaneous causality between this phenomenon and the inactivity rate is weaker. This might also depend on our choice to proxy the latter criminal phenomena with indicators of contrast activities, although goods might have been produced and sold not necessarily where they are seized.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2001). Good jobs versus bad jobs. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(1), 1–21.

Amable, B., & Gatti, D. (2004). The political economy of job protection and income redistribution. IZA Discussion Papers 1404. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Amable, B., & Gatti, D. (2006). Labor and product market reforms: questioning policy complementarity. Industrial and Corporate Change, 15(1), 101–122.

Amable, B., Demou, L., & Gatti, D. (2007). Employment performance and institutions: New answers to an old question. IZA Discussion Papers 2731. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Anderson, T. W., & Hsiao, C. (1982). Formulation and estimation of dynamic models using panel data. Journal of econometrics, 18(1), 47–82.

Arechavala, N. S., Espina, P. Z., & Trapero, B. P. (2015). The economic crisis and its effects on the quality of life in the European Union. Social Indicators Research, 120(2), 323–343.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–297.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 29–51.

Baker, D., Glyn, A., Howell, D., & Schmitt, J. (2003). Labor market institutions and unemployment: A critical assessment of the cross-country evidence. Economics Series Working Papers, 168.

Baker, D., Glyn, A., Howell, D., & Schmitt, J. (2004). Unemployment and labour market institutions: The failure of the empirical case for deregulation. ILO Working Paper, 43.

Baker, D., Glyn, A., Howell, D., & Schmitt, J. (2005). Labor market institutions and unemployment: A criticalassessment of the cross-country evidence. In Rose Stephen (Ed.), Fighting unemployment: The limits of free market orthodoxy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barkbu, B., J. Rahman, & R. Valdés. 2012. Fostering growth in Europe now. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/12/07. Washington, DC: IMF.

Becattini, G. (1997). Prato nel mondo che cambia (1954–1993). In G. Becattini (Ed.), Prato storia di una città. Il distretto industriale (1943–1993) (Vol. 4, pp. 465–600). Firenze: Le Monnier.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economicapproach. In G. F. Nigel, A. Clarke and R. Witt (Eds.), The economic dimensions of crime (pp. 13–68). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Belot, M., & Van Ours, J. C. (2004). Does the recent success of some OECD countries in lowering their unemployment rates lie in the clever design of their labor market reforms? Oxford Economic Papers, 56(4), 621–642.

Bicáková, A. (2005). Unemployment versus inactivity: An analysis of the earnings and labor force status of prime age men in France, the UK, and the US at the end of the 20th century. Luxembourg Income Study, Working Paper Series, (412).

Blanchard, O., & Giavazzi, F. (2003). Macroeconomic effects of regulation and deregulation in goods and labor markets. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 879–907.

Blanchard, O., & Wolfers, J. (2000). The role of shocks and institutions in the rise of European unemployment: The aggregate evidence. The Economic Journal, 110(462), 1–33.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87, 115–143.

Boeri, T., & Garibaldi, P. (2002). Shadow activity and unemployment in a depressed labour market. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 3433.

Boeri, T., & Jimeno, J. F. (2016). Learning from the great divergence in unemployment in Europe during the crisis. Labour Economics, 41, 32–46.

Boeri, T., Layard, R., & Nickell, S. (2000a). A welfare-to-work and the fight against long term unemployment. Report to Prime Ministers Blair and D’Alema, Mimeo.

Boeri T., Nicoletti G. & Scarpetta S. (2000b). Regulation and labour market performance. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 2420, April.

Bond, S. R. (2002). Dynamic panel data models: A guide to micro data methods and practice. Portuguese Economic Journal, 1(2), 141–162.

Brunello, G., Lupi, C., & Ordine, P. (2001). Widening differences in Italian regional unemployment. Labour Economics, 8(1), 103–129.

Burdett, K., Lagos, R., & Wright, R. (2003). Crime, inequality, and unemployment. The American Economic Review, 93(5), 1764–1777.

Cacciatore, M., Duval R., & Fiori G. (2012). Short-term gain or pain? A DSGE model-based analysis of the short-term effects of structural reforms in labour and product markets. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, no. 948. Paris: OECD.

Calmfors, L., & Driffill, J. (1988). Bargaining structure, corporatism and macroeconomic performance. Economic Policy, 3(6), 13–61.

Calzaroni, M., & Pascarella, C. (1998). Le unita di osservazione del processo produttivo nella nuova contabilita nazionale. Atti della XXXIX Riunione della Societa Italiana di statistica, Sorrento, aprile.

Carlin, W., & Soskice, D. (2005). Macroeconomics: Imperfections, institutions, and policies.OUP Catalogue.

Chang, J. J., & Wu, C. H. (2012). Crime, job searches, and economic growth. Atlantic Economic Journal, 40(1), 3–19.

Coe, D. T., & Snower, D. J. (1997). Policy complementarities: The case for fundamental labor market reform. IMF Staff Papers, 44(1), 1–35.

Commission of the European Communities, & Inter-Secretariat Working Group on National Accounts. (1993). System of national accounts 1993 (Vol. 2). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=575.0.

Daniele, V., & Marani, U. (2012). Organized crime and foreign investment: The Italian case. In C. Costa Storti & P. De Grauwe (Eds.), Illicit trade and the global economy (pp. 203–228). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Edmark, K. (2005). Unemployment and crime: Is there a connection? The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 107(2), 353–373.

Elmeskov, J., Martin, J. P., & Scarpetta, S. (1998). Key lessons for labour market reforms: Evidence from OECD countries’ experience. Swedish Economic Policy Review, 5(2), 205–252.

Essenburg, T. J. (2014). The new faces of American poverty: A reference guide to the great recession [2 volumes]: A reference guide to the great recession. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Estevão, M. (2005). Product market regulation and the benefits of wage moderation. IMF Working Paper 05/191. Washington, DC: IMF.

Everaert, L., & Schule, W. (2008). Why it pays to synchronize structural reforms in the Euro area across markets and countries. IMF Staff Papers, 55(2), 356–366.

Faggio, G., & Nickell, S. (2005). Inactivity among prime age men in the UK. LSE Research Online Documents on Economics 19912. London School of economics and Political Science, LSE Library.

Fiori, G., Nicoletti, G., Scarpetta, S., & Schiantarelli, F. (2012). Employment effects of product and labour market reforms: Are there synergies? Economic Journal, 122(558), 79–104.

Foged, M., & Peri, G. (2016). Immigrants’ effect on native workers: New analysis on longitudinal data. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8(2), 1–34.

Frattini, T. (2012). Immigrazione. Rivista di Politica Economica, 3, 363–407.

Freeman, R. B. (2005). Labour market institutions without blinders: The debate over flexibility and labour market performance. International Economic Journal, 19(2), 129–145.

Ghignoni, E., & Verashchagina, A. (2016). Added worker effectduring the Great Recession: evidence from Italy. International Journal of Manpower, 37(8), 1264–1285.

Gratteri, N., & Nicaso, A. (2010). La malapianta. Ilan: Edizioni Mondadori.

Gregg, P., & Wadsworth, J. (1998). Unemployment and non-employment: unpacking economic activity. Washington, D. C.: Employment Policy Institute.

Haffner, R. C. G., Nicoletti, G., Nickell, S., Scarpetta, S., & Zoega, G. (2000). European integration, liberalisation and labour market performance. In G. Bertola, T. Boeri, & G. Nicoletti (Eds.), Welfare and employment in a United Europe. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Holtz-Eakin, D., Newey, W., & Rosen, H. (1988). Estimating Vector Autoregressions with Panel Data. Econometrica, 56(6), 1371–1395.

International Monetary Fund. (2009). World economic outlook, October. Washington, DC: IMF.

ISTAT. (2011a). Occupati e disoccupati. Roma: ISTAT.

ISTAT. (2011b). La disoccupazione tra passato e presente. Roma: ISTAT.

Koeniger, W., & Prat, J. (2007). Employment protection, product market regulation and firm selection. The Economic Journal, 117(521), F302–F332.

Koeniger, W., & Vindigni, A. (2003). Employment protection and product market regulation (no. 880). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Lisi, G. (2010). Occupazioneirregolare e disoccupazione in Italia: un’analisi panel regionale [Underground employment and unemployment in Italy: A panel analysis] (No. 22508). Munich, Germany: University Library of Munich.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.

Malley, J., & Molana, H. (2008). Output, unemployment and Okun’s law: Some evidence from the G7. Economics Letters, 101(2), 113–115.

Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437.

Milone, L. M. (2016). The path of European structural reforms after the crisis: What has changed?. Mimeo: Department of Economics and Law, Sapienza University of Rome.

Moosa, I. A. (1997). A cross-country comparison of Okun’s coefficient. Journal of Comparative Economics, 24(3), 335–356.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1417–1426

Nickell, S. (1997). Unemployment and labor market rigidities: Europe versus North America. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11(3), 55–74.

Nickell, S., Nunziata, L., & Ochel, W. (2005). Unemployment in the OECD since the 1960s. What do we know? The Economic Journal, 115(500), 1–27.

Nicoletti, G. & S. Scarpetta. (2005). Product market reforms and employment in the OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, no. 472. Paris: OECD.

Nicoletti, G., & Scarpetta, S. (2002). Regulation, productivity and growth: OECD evidence. Paris: OECD.

Okun, A. M. (1963). Potential GNP: Its measurement and significance. New Haven: Yale University, Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (1997). Employment outlook. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2007). Economic policy reforms: Going for growth. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2008). The economic impact of counterfeiting and piracy. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2009). OECD economic surveys: European union. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2011). Persistence of high unemployment: What risks? What policies? OECD Economic Outlook, 2011, 1.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2015). In it together. Why less inequality benefits all. Paris: OECD.

Orszag, M., & Snower, D. (1999). Anatomy of policy complementarities. IZA Discussion Papers 41. Institute for the Study of Labor.

Overman, H. G., & Puga, D. (2002). Unemployment clusters across Europe’s regions and countries. Economic Policy, 17(34), 115–148.

Özel, H. A., Sezgin, F. H., & Topkaya, Ö. (2013). Investigation of economic growth and unemployment relationship for G7 Countries using panel regression analysis. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(6), 163–171.

Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in stata. Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136.

Schmitt, J., & Wadsworth, J. (2005). Is the OECD Jobs Strategybehind US and British employment and unemployment success in the 1990s?. In R. Stephen (Ed.), Fighting unemployment: The limits of free market orthodoxy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scognamiglio, A. (2015).When the Mafia Comes to Town. Centre for Studies in Economics and Finance (CSEF No. 404). Naples, Italy: University of Naples.

Siebert, H. (1997). Labor market rigidities: At the root of unemployment in Europe. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11(3), 37–54.

UNESCO. (2011). International standard classification of education, ISCED 2011. Unesco Institute for Statistics.

Visco, I. (2008). Invecchiamento della popolazione, immigrazione, crescita economica. Rivista Italiana degli Economisti, 13(2), 209–244.

Wasmer, E., & Weil, P. (2004). The macroeconomics of labor and credit market imperfections. The American Economic Review, 94(4), 944–963.

Watt, A., & Janssen, R. (2003). Unemployment and labour market institutions: Why reforms pay off. Chapter IV. IMF World Economic Outlook: Washington, D.C.

Windmeijer, F. (2005). A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. Journal of Econometrics, 126(1), 25–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fedeli, S., Mariella, V. & Onofri, M. Determinants of Joblessness During the Economic Crisis: Impact of Criminality in the Italian Labour Market. Soc Indic Res 139, 559–588 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1733-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1733-y