Abstract

In 2010 the Human Development Index (HDI) was revised with several major changes. Many of its problems were tackled, although some drawbacks still persist. This paper proposes a multi-criteria approach to measure human development, propounding two innovations for the computation of the HDI: (1) the introduction of a double reference point scheme in the normalization; (2) an aggregation function which deals with the problem of substitutability between components. In particular, for each component of the HDI the value of each country is normalized by means of two reference values (aspiration and reservation values) by using an achievement scalarizing function that is piecewise linear. Aggregating the new normalized values, we calculate a range of indices with different degrees of substitutability: (1) a weak index that allows total substitutability; (2) a strong index that measures the state of the worst component and allows no substitutability; and (3) a mixed index that is a combination of the first two.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a survey, see Kovacevic (2011), which was part of a comprehensive review undertaken by the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Some significant contributions are McGillivray (1991), Desai (1991), Kelley (1991), Dossel and Gounder (1994), Gormely (1995), Ravallion (1997), Palazzi and Lauri (1998), Anand and Sen (2000), Chakravarty (2003), Chatterjee (2005), Foster et al. (2005), Chowdhury and Squire (2006), Gaertner and Xu (2006), Lind (2010), Herrero et al. (2010), De Muro et al. (2011), Nguefack-Tsague et al. (2011), Pinar et al. (2013), Foster et al. (2012), Rende and Donduran (2013), etc.

Let us recall that, as highlighted by authors such as Desai (1991) and Palazzi and Lauri (1998), the additive form of the HDI is problematic because it implies perfect substitution across components. It assumes that the level of priority to be given to a component is invariant to the level of attainments. In addition, if a society were to seek policies to maximize its HDI, it might emphasize one component and disregard the others (see Klugman et al. 2011a).

Note that the range normalization is a particular case of our framework.

The HDI excludes other ‘broader dimensions’ of the concept of human development, such as empowerment, sustainability and equity. The 2010 HDR decided not to introduce any new dimensions in the HDI, stressing that the HDI can be characterized as an index of opportunities and freedoms, according to the two types of freedoms (opportunity freedoms and process freedoms) suggested by Sen (2002), that are valued by the human development approach (see, e.g., Klugman et al. 2011a).

Given that the transformation function from income to capabilities is likely to be concave (Anand and Sen 2000), the natural logarithm continues to be used to measure this HDI component.

UNDP (2011) reminds us that the low value for income can be justified by the considerable amount of unmeasured subsistence and nonmarket production in economies close to the minimum, not reflected in the official data.

In part, this is an empirical criterion similar to the one used by UNDP (2011) to set the minimum and maximum values (goalposts), according to the situation of countries worldwide in recent years.

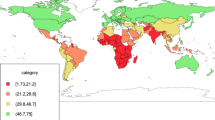

For the presentation of the results, we have selected the 10 most populated countries, which represent about 60 % of world population. These countries, listed on the basis of their HDI, are distributed amongst the 4 groups of countries as defined in the 2011 HDR: Very High Human Development (United States, Japan), High Human Development (Russian Federation, Brazil), Medium Human Development (China, Indonesia, India, Pakistan) and Low Human Development (Bangladesh, Nigeria).

We have carried out a sensitivity analysis of the weights of the components, showing that for a slight modification of one of them (for instance, 10 %) the ranking is almost equal (90 % of countries maintain their position or vary one or two positions), whereas major changes in the weights involve greater variations in the rankings. These results are in line with the role of the weights in the achievement scalarizing functions (see Luque et al. (2009) or Ruiz et al. (2009) for more details).

The results of Table 5 for all countries are available from the authors upon request.

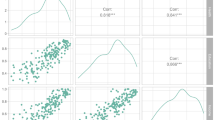

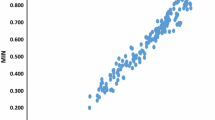

Specifically, Spearman’s correlation coefficient rho (ρ) amongst the ranks of countries listed according to the DRP-WI using criteria I and II is 0.999, and 0.992 amongst the DRP-SI ranks using both criteria.

References

Anand, S., & Sen, A. (2000). The income component of the human development index. Journal of Human Development, 1(1), 83–106.

Bilbao-Terol, A., Arenas-Parra, M., Cañal-Fernández, V., & Antomil-Ibias, J. (2014). Using TOPSIS for assessing the sustainability of government bond funds. Omega, 49, 1–17.

Bilbao-Ubillos, J. (2013). Another approach to measuring human development: The composite dynamic Human Development Index. Social Indicators Research, 111, 473–484.

Chakravarty, S. (2003). A generalized Human Development Index. Review of Development Economics, 7(1), 99–114.

Chakravarty, S. (2011). A reconsideration of the tradeoffs in the human development index. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9, 471–474.

Chatterjee, S. K. (2005). Measurement of human development—An alternative approach. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 31–53.

Chowdhury, S., & Squire, L. (2006). Setting weights for aggregate indices: An application to the commitment to development index and Human Development Index. Journal of Development Studies, 42(5), 761–771.

De Muro, P., Mazziotta, M., & Pareto, A. (2011). Composite indices of development and poverty: An application to MDGs. Social Indicators Research, 104, 1–18.

Desai, M. (1991). Human development: Concepts and measurement. European Economic Review, 35(2/3), 350–357.

Dossel, D. P., & Gounder, R. (1994). Theory and measurement of living levels: Some empirical results for the Human Development Index. Journal of International Development, 6, 415–435.

Foster, J. E., Lopez-Calva, L. F., & Szekely, M. (2005). Measuring distribution of human development: Methodology and an application to Mexico. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 5–25.

Foster, J., McGillivray, M., & Seth, S. (2012). Composite indices: Rank robustness, statistical association, and redundancy. Econometric Reviews, 32(1), 35–56.

Gaertner, W., & Xu, Y. (2006). Capability sets as the basis of a new measure of human development. Journal of Human Development, 7(3), 311–321.

Gormely, P. J. (1995). The Human Development Index in 1994: Impact of income on country rank. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 21, 253–267.

Herrero, C., Martínez, R., & Villar, A. (2010). Multidimensional social evaluation: An application to the measurement of human development. Review of Income Wealth, 56(3), 483–497.

Herrero, C., Martínez, R., & Villar, A. (2012). A newer Human Development Index. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 13(2), 247–268.

Hwang, C. L., & Yoon, K. P. (1981). Multiple attribute decision making: Methods and applications survey. New York: Springer.

Kelley, A. C. (1991). The human development index: “handle with care”. Population and Development Reviews, 17(2), 315–324.

Klugman, J., Rodríguez, F., & Choi, H.-J. (2011a). The HDI 2010: New controversies, old critiques. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(2), 249–288.

Klugman, J., Rodríguez, F., & Choi, H.-J. (2011b). Response to Martin Ravallion. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 9, 497–499.

Kovacevic, M. (2011). Review of HDI critiques and potential improvements. Human Development Research Paper 2010/33. New York: UNDP.

Lind, N. (2010). A calibrated index of human development. Social Indicators Research, 98, 301–319.

Luque, M., Miettinen, K., Eskelinen, P., & Ruiz, F. (2009). Incorporating preference information in interactive reference point methods for multiobjective optimization. OMEGA—International Journal of Management Science, 37(2), 450–462.

Luque, M., Ruiz, F., & Steuer, R. E. (2010). Modified interactive Chebyshev Algorithm (MICA) for convex multiobjective programming. European Journal of Operational Research, 204, 557–564.

McGillivray, M. (1991). The Human Development Index: Yet another redundant composite development indicator? World Development, 19, 1461–1468.

Miettinen, K. (1999). Nonlinear multiobjective optimization. Boston: Kluwer.

Nguefack-Tsague, G., Klasen, S., & Zucchini, W. (2011). On weighting the components of the human development index: A statistical justification. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 12(2), 183–202.

Palazzi, P., & Lauri, A. (1998). The Human Development Index: Suggested corrections. Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review, 51(205), 193–221.

Pinar, M., Stengos, T., & Topaloglou, N. (2013). Measuring human development: A stochastic dominance approach. Journal Economic Growth, 18(1), 69–108.

Ravallion, M. (1997). Good and bad growth: The human development reports. World Development, 25(5), 631–638.

Ravallion, M. (2010). Troubling tradeoffs in the Human Development Index. Policy Research Working Paper No. 5484, World Bank.

Ravallion, M. (2011). The human development index: A response to Klugman, Rodríguez and Choi. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(3), 475–478.

Ravallion, M. (2012). Troubling tradeoffs in the Human Development Index. Journal of Development Economics, 99, 201–209.

Rende, S., & Donduran, M. (2013). Neighborhoods in development: Human Development Index and self-organizing maps. Social Indicators Research, 110, 721–734.

Ruiz, F., Luque, M., & Cabello, J. M. (2009). A classification of the weighting schemes in reference point procedures for multiobjective programming. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60(4), 544–553.

Sen, A. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Sen, A. (2002). Rationality and freedom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Tofallis, C. (2012). An automatic-democratic approach to weight setting for the new human development index. Journal of Population Economics.

Ul Haq, M. (1995). Reflections on human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

UNDP. (1990). Human development report 1990. Concept and measurement of human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

UNDP. (2010). Human Development Report 2010–20th Anniversary edition. Pathways to human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

UNDP (2011). Human Development Report 2011. Sustainability and equity: A better future for all. New York: UNDP.

Wierzbicki, A. P. (1980). Multiple criteria decision making theory and application. In G. Fandel & T. Gal (Eds.), Lecture notes in economics and mathematicas systems 177, the use of reference objectives in multiobjective optimization (pp. 468–486). Heidelberg: Springer.

Wierzbicki, A. P., Makowski, M., & Wessels, J. (Eds.). (2000). Model-based decision support methodology with environmental applications. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

World Bank (2013). How to classify countries. http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications. World Bank. Accessed 25 February 2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luque, M., Pérez-Moreno, S. & Rodríguez, B. Measuring Human Development: A Multi-criteria Approach. Soc Indic Res 125, 713–733 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0874-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0874-0