Abstract

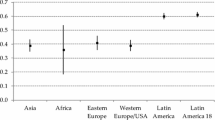

This paper is aimed at presenting a new intergenerational mobility index that (a) combines the intergenerational elasticity and the R-squared of the intergenerational regression and (b) enables the expression of the total degree of mobility as the weighted sum of mobility with respect to both parents. As a case study, we apply our proposal to investigate the intergenerational mobility of education in several European countries and its changes across birth cohorts. The results derived from the proposed index indicate that Nordic countries display higher levels of educational mobility than Southern countries, whereas continental countries are in an intermediate position. Moreover, it appears that the degree of mobility increases over time only in those countries with low initial levels and remains stable for the most mobile countries. Finally, for most of the countries the proposed methodology can prove that the degree of educational mobility with respect to each parent tends to converge to the same level over the course of time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Namely: Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden (Nordic countries); Austria, Belgium, France and the Netherlands (Continental countries); Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain (Southern countries). We found serious anomalies in the original EU-SILC data referring to parental level of education in the cases of Germany and the United Kingdom that prevented us from using these countries in our analyses. After we sought information from EUROSTAT, it was clear that there were problems with the original data collection and codification that could not be solved subsequently. On the one hand, EU-SILC German data on the parental level of education are affected by lack of homogeneity between the classifications used in East and West Germany. This caused an overrepresentation of the ISCED 5 level, which may be verified by comparing original EU-SILC German data with European Social Survey data (2006 wave) and also with data drawn from the German Socio-Economic Panel (2003), as shown by Heineck and Riphahn (2009). On the other hand, data referring to the United Kingdom present a serious problem with severe overrepresentation of cases coded as ISCED 0; this overrepresentation may be confirmed through a comparison with European Social Survey data (2006 wave).

Additionally, Checchi et al. (2008) propose an intuitive decomposition of the correlation coefficient, whose results are highly appealing for the analysis of temporal changes because they may account for changes in composition effects and thus provide the “correct measure for analysing intergenerational transmission of education” (the marginal probability of children’s education, conditional to that of the parents).

Note that the R-squared from the bivariate regression between parental and children’s schooling represents the square of the correlation coefficient between the two variables.

Note that the betas obtained from these regressions, where the dependent as well as the explanatory variables are expressed in terms of deviation from the respective means, are exactly the same as those that can be obtained from the OLS regressions with the original level variables plus an intercept term.

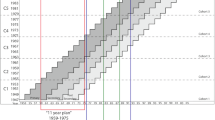

Given that the additional questionnaire on family characteristics during childhood in the EU-SILC is only directed at individuals aged between 25 and 65 in 2005, we consider the first birth cohort 1940–1945 and the last 1975–1980. Table 1 contains the complete definition of birth cohorts, and the number of observations for each cohort for the selected European countries. In the case of Denmark, we cannot consider the first two birth cohorts (1940–1945 and 1945–1950), because the information on maternal education is not reliable (maternal education in the first two cohorts is fixed for all observations to ISCED2). We preferred to exclude these two initial cohorts from the analysis rather than compute mobility only with respect to parental education.

In Table 2 we report the detailed information on the conversion of ISCED levels into equivalent years of education. Note also that we retain observations of native-born individuals who are no longer studying in the year of the survey (2005), with valid information about own, paternal and maternal completed education. We use only the sub-sample of native-born individuals because (a) we aim to relate the patterns of educational mobility to institutional changes, and (b) we want to avoid including individuals who have potentially been exposed to different institutional environments. For reasons of brevity, we neglect gender differences, which will be a subject of future research on this topic.

As in Nicoletti and Ermisch (2007) and in Mayer and Lopoo (2005) we have also tested a rolling specification, by progressively adding 1 year to each 5-year birth cohort (1940–1945, 1942–1946 and so on). However, this specification does not modify the general results, nor does it affect the temporal patterns of the mobility index (it only artificially increases the number of points in which the mobility index is calculated).

Note that in the case of France we observe a moderate decrease in educational mobility from the 1956–1960 cohorts, but it increases again from 1966 to 1970, reaching its high initial levels. Moreover, in Austria there is a pronounced inflection between the 1940–1945 and the 1955–1960 cohort. However, educational mobility is essentially stable up to the end of the period.

Unfortunately, as noted above, we cannot provide a measure of educational mobility in the first cohorts, owing to problems with the information about completed maternal education; however, we suppose that educational mobility at the starting-point was significantly high in Denmark.

Note that in both Belgium and the Netherlands but also in Greece, educational mobility seems to decline in the last cohort (1975–1980). However, this may simply be the result of the exclusion from the sample of those individuals who were still studying in the year of the survey (2005). In all likelihood, these individuals are enrolled in higher education, and dropping them from the sample may reduce the observed degree of mobility in this cohort. In fact, in order to avoid distorting the results, the mean rate of increase of 0.02 has been computed with respect to the first seven cohorts.

In this country, there is a clear switch in the role of the two parents in the 1965–1970 cohort: in fact, in this cohort the child’s education was previously more attached to parental education, but maternal education later has a stronger effect until the end of the period.

References

Black, S. E. & Devereux, P. J. (2010). Recent developments in intergenerational mobility. In Handbook of labor economics. (forthcoming).

Blanden, J. (2009). Intergenerational income mobility in a comparative perspective. In R. Apslund, E. Barth, & P. Dolton (Eds.), Education and inequality across Europe. Massachusetts: Edward Edgar.

Checchi, D. (2006) The economics of education. human capital, family background and inequality. Cambridge University Press.

Checchi, D., Ichino, A., & Rustichini, A. (1999). More equal but less mobile? Education financing and intergenerational mobility in Italy and in the US. Journal of Public Economics, 74(3), 351–393.

Checchi, D., Fiorio, C. V. & Leonardi, M. (2008). Intergenerational persistence in educational attainment in Italy, IZA Discussion papers 3622, Institute for the study of labor (IZA).

Chevalier, A., Denny, K., & McMahon, D. (2009). A multi-country study of inter-generational educational mobility. In R. Apslund, E. Barth, & P. Dolton (Eds.), Education and inequality across Europe. Massachusetts: Edward Edgar.

Comi, S. (2003). Intergenerational mobility in Europe: evidence from ECHP, Departemental Working Papers 2003–03. Department of Economics, University of Milan, Italy.

Corak, M. (2004). Generational mobility in North America and Europe: An introduction. In M. Corak (Ed.), Generational mobility in North America and Europe. UK: Cambridge university press.

Erikson, R., & Godthorpe, J. H. (2002). Intergenerational inequality: A sociological perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16, 31–44.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2004). Unequal opportunities and the mechanisms of social inheritance. In M. Corak (Ed.), Generational mobility in North America and Europe. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Goldthorpe, J. H., & Mills, C. (2005). Trends in intergenerational class mobility in Britain in the late twentieth century. In R. Breen (Ed.), Social mobility in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heineck, G. & Riphahn, R. T. (2009). Intergenerational transmission of educational attainment in Germany––The last five decades. Journal of Economics and Statistics (Jahrbuecher fuer Nationaloekonomie und Statistik), Justus-Liebig University Giessen, Department of Statistics and Economics (vol. 229(1), pp. 36–60).

Hertz, T., Jayasundera, T., Piraino, P. Selcuk, S., Smith, N. & Verashchagina, A. (2008) The inheritance of educational inequality: International comparisons and fifty-year trends. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 7(2) (Advances), Article 10.

Mayer, S. E., & Lopoo, L. M. (2005). Has the intergenerational transmission of economic status changed? The Journal of Human Resources, 40, 169–185.

Nicoletti, C. & Ermisch, J. (2007). Intergenerational earnings mobility: Changes across cohorts in Britain. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 7(2) (Contributions), Article 9.

Piketty, T. (2000). Theories of persistent inequality and intergenerational mobility. Handbook of income distribution. In A.B. Atkinson, & F. Bourguignon (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution (edition 1, vol. 1, chapter 8, pp. 429–476).

Raymond, J. L., Roig, J. L., & Gómez, L. (2009). Rendimientos de la educación en españa y movilidad intergeneracional. Papeles de Economía Española, 119, 188–205.

Solon, G. (1999). Intergenerational mobility in the labor market. In Orley Ashenfelter, & David Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1761–1800). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Solon, G. (2002). Cross-country differences in intergenerational earnings mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3), 59–66.

Solon, G. (2004). A model of intergenerational mobility variation over time and place. In M. Corak (Ed.), Generational income mobility in North America and Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciated all the comments received in the “First Lisbon Research Workshop on Economics and Econometrics of Education” and in the “ZEW Workshop of Education and Equality of Opportunity”. Antonio Di Paolo and Josep Lluís Raymond acknowledge the financial support from the MEC grant ECO2010-20718. Jorge Calero acknowledges the support of the “Interdisciplinary Group on Educational Policy (2009-SGR252)” and Josep Lluís Raymond acknowledges the support of the “Research Group in Applied Economics (2009-SGR478)”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Di Paolo, A., Raymond, J.L. & Calero, J. A New Proposal to Gauge Intergenerational Mobility: Educational Mobility in Europe as a Case Study. Soc Indic Res 114, 947–962 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0183-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0183-9