Abstract

We develop a new theoretical framework that explains the engagement in child labor of children in developing countries. This framework distinguishes three levels (household, district and nation) and three groups of explanatory variables: Resources, Structure and Culture. Each of the three groups refers to another strand of the literature; economics, sociology and anthropology. The framework is tested by applying multilevel analysis on data for 239,120 children living in 221 districts of 18 developing countries. This approach allows us to simultaneously investigate effects of household and context factors. At the household level, we find that resources and structural characteristics influence child labor, whereas cultural characteristics have no effect. With regard to context factors, we find that children work more in rural areas, especially if there are more unskilled manual jobs, and in more traditional urban areas. In more developed regions, girls tend to work significantly less.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A worldwide consensus exists that child labor should be eradicated and that it is in the interest of both the children and the country as a whole that all children go to school (UNICEF 2008; Sen 1999; Barro 1999; Case 2001; World Bank 2002). Hence, during the last decades governments and donor organizations have done major efforts to reduce child labor throughout the developing world. In spite of these efforts, still over 200 million children are estimated to be working as child laborers worldwide (ILO-IPEC 2010). To improve this situation, it is of fundamental importance to gain a better understanding of the factors that influence the decisions of parents (or other caretakers) regarding the engagement in paid employment of their children. Likewise, policies directed at reducing child labor can only be effective if they are based on a thorough understanding of the forces by which young children are pushed or pulled into the labor market.

Most child labor research focuses on predictors at one level, either the family level (e.g. Basu et al. 2007; Buchmann 2000; Patrinos and Psacharopoulos 1997) or the national level (e.g. Kis-Katos and Schulze 2006; Fan 2004; Levy 1985). The determinants of child labor are not restricted to one level, however. The parental decisions regarding child labor depend not only on characteristics of parents and their households, but just as well on the presence of job opportunities for children at the local labor market and on the characteristics of the available educational facilities. Hence, to obtain an encompassing understanding of the roots of child labor, the relevant factors at the different levels (household, district and national) should be studied simultaneously. Recently, researchers of child labour and school enrollment acknowledge the necessity of such a multilevel approach (Manacorda and Rosati 2007; Baschieri and Falkingham 2006; Kis-Katos and Schulze 2006; Smits 2007; Huisman and Smits 2009). The current paper fulfills this necessity by simultaneously analyzing the effects of (family) background characteristics and characteristics of the context in which the family lives on engagement in child labor of children.

Based on theoretical ideas from different disciplines, an encompassing theoretical framework is developed which includes explanatory factors at the household, district and national level. This framework distinguishes three conditions affecting child labor which manifest themselves differently at different levels of analysis: resources, structure and culture. Besides direct influences, the framework allows for interactions across levels and for studying the determinants in their specific contexts. The hypotheses derived from this framework are tested by means of a unique database, containing information of 239,120 children aged 8–13 and their families, living in eighteen developing countries from different regions of the developing world. For each of these children we know whether or not they are engaged in paid labor and we have information on the socio-economic and demographic characteristics of their family background. This household-level information is combined with information about the sub-national region (henceforth called ‘district’) and the country in which the children live. As we can distinguish 221 districts in the eighteen countries, there is ample explanatory power at the district level that can be used to test hypotheses on context effects. The context information includes indicators of level of development, degree of urbanization, the position of women and the quality of the available educational facilities.

The data are analyzed with multi-level logistic regression models that enable us to estimate effects of factors at household, district and national level simultaneously. To address within this framework of large-scale quantitative analysis the fact that each situation is unique—and hence that the effects of the various factors might differ depending on the circumstances—besides direct effects of the explanatory factors also interactions between household-level factors and characteristics of the context are studied. The information thus obtained might be helpful in developing tailor-made policy interventions aimed at reducing child labor.

2 A Comprehensive Framework

As discussed in the Introduction, an encompassing understanding of the roots of child labor can only be obtained if the relevant factors at different levels are studied simultaneously. To guide such an analysis, we have developed a new framework for explaining child labor, inspired by models for understanding women’s labor (c.f. Spierings et al. 2010; Hijab 2001). Our framework is based on four pillars: (1) The context in which children live has different levels (household, local, national), (2) Decisions regarding child labor are made at the household level, by parents, caretakers and/or other family members, (3) Different factors at the different levels influence these decisions simultaneously, (4) The strength of these influences may differ between contexts.

Our model is presented in Fig. 1. The child is placed in the centre. It is embedded in a multilayered context (household, local, national). We can think of these layers as concentric circles, with the relevant factors at the inner or lower levels embedded within—and affected by—the outer or higher levels, thus allowing for context-specific effects (compare Spierings et al. 2010). The major decision makers regarding child’s work or education are located at the household level. Decision makers are generally the parents or caretakers of the child, but other family members may also have a voice. The decision has four possible outcomes (as shown in the center of the model): the child can be in school, it can be engaged in paid work, it can be both in school and engaged in paid work and it can be neither in school nor engaged in paid work. In the literature, the last situation is sometimes called ‘idle’ (Maitra et al. 2006; Biggeri et al. 2003; Bocolod and Ranjan 2008), although the child generally is not really idle but engaged in household work or work at the family business (Webbink et al. 2011). In this paper, we reserve the term child labor for children engaged in paid employment (with payment being either in cash or in kind).

To comprehend how the multitude of risk factors shapes the outcome of the decision, they are grouped into three conditions according to the underlying causal mechanisms: resources, structure and culture. These conditions are associated with different strands of literature regarding child labor in developing countries: (1) the (economic) literature focusing on resources, (2) studies which stress the importance of structural factors and (3) (anthropological) work that explains child labor with cultural factors. Economists, such as Basu and Van (1998), state that child labor is an economic decision made by parents in order to survive (Grootaert and Kanbur 1995; Ranjan 1999). Other authors stress the importance of family structure factors (such as the number of siblings) (Edmonds 2006) or the labor market structure (Emerson and Souza 2008; Duryea and Arends-Kuenning 2003); hence we consider them structural variables. Our third group of variables is derived from the literature on cultural explanations (Lieten 2003; López-Calva 2002; Nieuwenhuys 1994; Delap 2001). The many factors related to child labor in Fig. 1 can be understood in terms of how they shape or reflect certain resources, structural characteristics and cultural factors. As explained before, we assume that it is likely that these factors influence the child labor decision simultaneously. In the next section, the conditions will be discussed in more detail.

2.1 Resources

The most important resources at the household level are income/wealth, parental education and work. Income or wealth is probably most relevant in this respect. The poverty hypothesis, or luxury axiom (Basu and Van 1998), assumes that when a household earns enough, there is no need to generate income from child labor. Parental education is another socio-economic resource. Parents who have reached a certain educational level can be expected to want their children to reach at least the same level (Breen and Goldthorpe 1997). Empirical research shows that school enrollment is, to a large extent, influenced by the education of the mother (Huisman and Smits 2009) and that it is more important than father’s education in child labor decisions in rural India (Kurosaki et al. 2006).

In developing countries, where many children grow up to do a job similar to their parents, we expect a strong relationship between parents’ and children’s present and future occupations. For some professions, like agricultural work and basic industries, this means that parents might believe that training by doing has more value than formal education (Bass 2004; Smits and Gündüz Hoşgör 2006; Lieten 2003; Beegle et al. 2004). We expect that boys with fathers working in lower non-farm occupations will work more, as they may be prepared for taking over the family enterprise or other jobs with low education requirements. As girls are often expected to marry into the family of their husband (Bass 2004), they will be more likely trained in doing the household chores in order to be a good housewife. In this case, parents may find investing in educating their daughters not worthwhile as there are no direct returns for the family (Gündüz Hoşgör and Smits 2008; Huisman and Smits 2009). Since working mothers will bring more income into the household, we may consider mother’s work outside the home a resource. On the other hand, there is also evidence that children with gainfully employed mothers work more (Francavilla and Gianelli 2007; Bhalotra 2003), among others because children go along with their mother when she works.

Economic development at the district level is placed under context-level resources. In general, in more modern areas, there is more impact of globalization, including the diffusion of value patterns that stress the importance of education and gender equality. In urban areas, the road and transport infrastructure is generally better, the state influence is stronger and there may be more pressure on parents to send their children to school. Nevertheless, the effect of development on child labor is not clear-cut. For instance, when agricultural machines replace unskilled agricultural workers, the demand for child labor tends to drop. On the other hand, mechanization can also increase the demand for child labor in factories, as happened during the Industrial Revolution (Nardinelli 1980). Others argue that more community wealth might lead to more apprenticeship opportunities, thus a higher demand for child labor (Nkamleu and Kielland 2006).

Another important context resource factor is the educational level of the community. When surrounded by educated adults, we expect parents to experience that education is a prerequisite to acquire human capital (Becker 1993) and better labor market opportunities. We therefore expect lower levels of child labor in areas with a higher level of education. Besides that, a higher community educational level is also an indicator for better educational infrastructures, which could also be seen as a structural characteristic. We discuss this more extensively in the following section.

2.2 Structure

Structural characteristics at the household level often are resource-dilution variables. Individuals with more siblings might be more engaged in child labor because resources have to be distributed among more family members. On the other hand, more siblings might also mean more helping hands. This may lead to more time for school for each child (Patrinos and Psacharopoulos 1997) or, as resources tend to be unequally distributed within households (Buchmann 2000), to child labor for some and schooling for others. Other structural characteristics of the household may lead to more access to resources. In extended families there is more manpower to generate income or do housework; hence, children are expected to work less. On the other hand, when the father or mother is missing from a household, children can be expected to work more.

Birth order might be important too. There are indications that firstborn children have fewer opportunities than their younger siblings (Chesnokova and Vaithianathan 2008; Edmonds 2006). Under difficult circumstances, the older children may have to work for pay or help at home and their labor may create the opportunity to go to school for their younger siblings (Edmonds 2008). Because the sibling composition might also matter—girls are more often involved in housework (Webbink et al. 2011)—it is important to make a distinction between the presence of brothers and sisters. Children with more brothers might be less engaged in commercial work, because there are literally more candidates to do the job (Edmonds 2006).

As paid child labor is often used to make ends meet (Nkamleu and Kielland 2006), we expect that foster children are more engaged in this kind of work. Parents might prefer their own kin to receive a better education since children are a means of old age social security (Bhalotra and Heady 2000). However, because they might take over or inherit the enterprise, work experience on the family farm or own business might also be important for biological children.

Structural resources at the context level may offer opportunities as well as restrictions. Since there are many differences between urban and rural areas, urbanization might be an important structural factor. Generally speaking, agriculture accounts for 60–70% of child labor worldwide (ILO-IPEC 2006b, p. 8; 2008, p. 13) and this mostly takes place in rural areas. Child labor is generally low or unskilled work, as young children are not educated and have little work experience. Therefore, children will work more in areas with a higher demand for unskilled manual work. Opportunities for paid employment in rural areas will primarily be located on larger farms (e.g. tobacco or cacao) or in the mining industry. According to ILO-IPEC (2010), child labor in urban areas is mostly an informal sector phenomenon. Children also work in factories or sweatshops, but this is a relatively low proportion. Because of this ambiguous relationship we do not formulate a clear-cut hypothesis on the relationship between child labor and urbanization. We do expect considerable differences between the effects of other characteristics in urban and rural areas, and elaborate on this difference more in the section on interaction effects.

As mentioned in the previous section, the availability of educational facilities could also be regarded as a structural characteristic. When there are no (good) schools in the vicinity, children are forced to work or to remain idle (Kondylis and Manacorda 2006).

2.3 Culture

Norms and values regarding child labor are expected to influence parent’s attitudes towards child labor. Cultural factors can be distinguished in values about the labor market participation of children (and views on childhood) and the role of women in the public sphere and the adaptation of modern values. We will focus on the role of women and traditionalism.

In general, women’s empowerment is believed to improve the wellbeing, health (Mukherjee and Das 2008; Hobcraft 1993) and schooling of their children (Huisman and Smits 2009). More empowered women are more capable of using their influence to the benefit of their children (Das and Mukherjee 2007). This will affect both boys and girls. A factor that possibly influences child labor participation of girls is patriarchy. Parents with more patriarchal values probably invest more in the education of sons (Kambhampati and Rajan 2008), since their daughters will marry out the family. They might keep their daughters out of school to help with the household chores, but probably will not easily let them work for pay outside the home (Kambhampati and Rajan 2008; Dyson and Moore 1983). We test for patriarchal values at both the household and the context level.

Another factor that influences child labor by girls is the role of women in the public sphere. Women (and girls) work less in areas with a taboo on women working in the public sphere (Spierings et al. 2010). However, girls living in these areas might not fully profit from these circumstances, because they might be less enrolled in school in these areas as well (Sundaram and Vanneman 2008).

2.4 Rural Versus Urban

Our framework’s fourth pillar is the idea that effects of determinants of child labor may be different under different circumstances. In this respect we will focus on the role of differences in level of development, as indicated by the variation between urban and rural areas. In more developed/urban areas, the educational infrastructure is generally better, allowing children to go to school more frequently, even when they are (relatively) poor. On the other hand, it seems likely that under more difficult circumstances as experienced in rural areas of many developing countries, parents with more resources will have less need to let their children work than parents with fewer resources. Based on this idea, we pose several hypotheses on the interactions of resource, structural and cultural factors and urbanization. Since there is not much theory on the nature of interactions like these, this work is explorative in character.

The influence of the resource variable wealth might be nonlinear. According to the luxury axiom (Basu and Van 1998), child labor only occurs in poor families living below a given subsistence level. Indeed, recent research indicates that the effect of income might not be linear. Up to a certain threshold, poverty seems to be the driving force behind child labor, but as households obtain more resources, other factors become important (e.g. parental education) (Self and Grabowski 2009). This could partly explain why some poor children are engaged in child labor and others are not. There is broad evidence that parents with more resources or motivation are better able to get their children into school (Filmer and Pritchett 1999; Handa 2002; Mugisha 2006; Huisman and Smits 2009). If poor parents cannot afford schooling, this does however, not simply imply that poor children work for pay. It could be that these children have to do housework or help at the farm or family business (Webbink et al. 2011). This choice for ‘idleness’ is most likely in areas with no demand for child labor, effectively enforced child labor laws or a strong public opinion against child labor. We therefore expect that the effect of poverty is smaller in contexts with a lower demand for child labor, or where child labor is prohibited by moral values or law. As laws on school enrollment and child labor are probably less strictly enforced in areas with a poorer infrastructure such as rural areas, we expect wealth at the household level to matter more in rural areas. Similarly, we hypothesize that the district level of development has a significantly weaker or no effect in urban areas on the involvement in paid employment by rural children.

With respect to the resource variable parental education, we expect that higher educated parents will find ways to educate their children even if they live under harder circumstances in rural areas. Moreover, as discussed in the previous section, empowered women may be more capable to educate their children and protect them from child labor. In urban areas, the level of women’s empowerment is generally higher. We therefore expect that the effect of empowerment will be reinforced there, because prevailing norms on child labor and support of other women will help mothers to get their children into school and out of child labor.

3 Data and Methods

The data are derived from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (see: www.measuredhs.com). These are large representative household surveys held since the 1980s in many developing countries. We use recent surveys for eighteen countries; Benin 2006, Bangladesh 2004, Chad 2004, Congo DR 2007, Congo-Brazzaville 2005, Egypt 2005, Liberia 2007, Morocco 2003, Mali 2001, Malawi 2004, Senegal 2005, Sierra Leone 2008, Uganda 2001, Colombia 2000, Dominican Republic 2007, Nicaragua 2001, Peru 2004–2008 and India 2006. These countries are chosen because their DHS data include information on the labor market participation of young children. Within these countries we distinguish 221 districts. The total number of children aged 8–13 available for our analyses is 239,120 of which 121,943 boys and 117,177 girls.

Besides household-level data, we use context information at the district level. The district-level information is derived by aggregating from the household surveys. Because the samples are large, we could create district-level indicators by taking the district’s average of characteristics of households and individuals (compare Huisman and Smits 2009).

3.1 Methods

The effect of family background and district characteristics on the participation in child labor is studied using multilevel logistic regression analysis (Hox 2002; Snijders and Bosker 1999). We apply three-level multilevel models because we use data on families nested within districts nested within countries and we include explanatory variables at each of the household levels and district level. In all analyses robust standard errors (sandwich estimators) are used. The dependent variable is a dummy variable indicating whether (1) or not (0) the child performed any economic activity for non-household members in the week before the survey. We restrict our analyses to children aged 8–13. The upper limit was chosen because the ILO-conventions on child labor permit light work for 14 and 15 year-olds in developing countries. To determine to what degree the effect of our independent variables differs between boys and girls and between urban and rural areas, interactions between all independent variables and gender and living in a rural area were tested and included into the model if found significant. To compute these interaction terms, centered versions of the involved variables were used. The main effects, therefore, can be interpreted as average effects. Given the large number of possible interactions, only significant interactions were included.

3.2 Variables

Independent variables at the household level are socio-economic characteristics (parental education, household wealth), demographic characteristics (sex, age, number of brothers and sisters, birth order, whether or not the child is a biological child and household composition). Since income is lacking in most of the surveys, household wealth is used as an alternative. Household wealth is measured by an index constructed on the basis of household assets, such as TVs, cars, telephones, and housing characteristics (such as floor material, roofing, toilet facilities). Using a method developed by Filmer and Pritchett (1998), we ranked all households within a country from low to high on the basis of their assets and subsequently divided this variable into wealth deciles.

Father’s occupation is measured with three categories: (1) farm, (2) lower nonfarm (sales, service and manual occupations), (3) upper nonfarm (professional, managerial, technical and clerical occupations). Employment of the mother is a dummy indicating whether (1) or not (0) the mother is employed. Education of the father and mother are measured in years. Children with a missing parent were given the mean score of the other children in the database on the variables indicating characteristics of the parents. Because there are dummies indicating whether or not the mother or father is missing in the model, this procedure leads to unbiased estimates of these variables (Allison 2001, note 4).

Age of the child is measured in years. Number of sisters and brothers and birth order are measured by interval variables. Presence of the parents is measured with two dummy variables indicating whether (1) or not (0) the mother or father is missing from the household. Extended family structure is measured with three categories (0) nuclear family, (1) more than two adults in the household but no grandparents, (2) more than two adults in the household including grandparents. To indicate traditional value patterns at the household level we included a dummy when the mother had her first child under the age of eighteen (1) and the age difference between spouses (interval variable). We also included a dummy indicating whether (1) or not (0) the household lives in a rural area.

District level of development is measured by the percentage of households with a TV in the district. To indicate the level of the local schooling facilities, we calculated the mean number of years of education for men above the age of 13. The proportion of men in lower nonfarm labor is included as a measure for the demand for child labor. As a measure of traditionalism of the district we use the mean difference in age between husbands and wives (age husband minus age wife). In more traditional societies, the age difference between husbands and wives tends to be larger than in more modern societies, so the higher the mean difference, the more traditional a district is expected to be. Patriarchy is indicated by the percentage of married couples living in households with grandparents from father’s side, indicating the tendency of girls to be married into the family of their husband.

4 Results

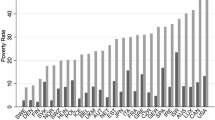

Figure 2 presents percentages of boys and girls engaged in child labor. They show that children are more engaged in child labor in Africa than in Latin America and Asia. Only in Nicaragua, the percentage of boys engaged in child labor is with 17% comparable to some African countries. Children living in Benin and Uganda are mostly engaged in child labor, with 30–50% of working children. Children in Egypt, Colombia and Dominican Republic are least involved, with between 0.3 and 5% of the children reporting to work for pay. In Africa, there are striking differences between the countries, with percentage ranging from 0.3 (Egypt) to 50 (Benin). In South Asia (India and Bangladesh, the incidence of child labor is with 4–10% relatively low compared to the other regions, but it still implies that millions of Asian children work for pay.

A second important finding is the difference between boys and girls. In some countries boys work much more than girls. The absolute difference between boys and girls is largest in Benin, with 30% of girls and 50% of boys engaged in paid work. In Bangladesh, the difference between boys and girls is also considerable. Both countries have a large Muslim community, in which the labor market engagement of women is comparatively low (Spierings et al. 2010). The gender difference is largest in Nicaragua, with four times more boys than girls working. Only in Malawi and Liberia, girls are slightly more engaged in child labor than boys.

Figure 3 shows the difference in child labor engagement between urban and rural areas. In most countries the incidence of child labor is substantially higher in rural areas. Children in these countries probably are engaged in labor intensive agriculture (tobacco, tea, groundnuts, cacao etc.) and in mining (diamonds, coals etc.) (ILO-IPEC 2006a; Hindman 2009). Exceptions are Bangladesh, Mali and India, where children in urban areas work more. In these countries the demand for commercial child labor is more located in work in factories or sweatshops in the carpet—and cigarette industry (Global March 2011).

The relationship between wealth and child labor also varies much among the countries (Fig. 4). In Latin America, the largest differences (about 10%) between the poorest and upper wealth quintiles are found in Peru and Nicaragua. On the whole, the results for Latin America suggest a negative linear relationship between wealth and child labor. This is not the case in Africa, where a very substantial percentage of the children from the upper wealth quintile are economically active. In Mali, there is even a completely reversed pattern with (somewhat) more child labor in the upper wealth quintile than the lowest. It should however, be taken into account that the wealth index is a relative index, hence the highest 20% of a poor country may on average be still relatively poor.

In Chad, Congo Brazzaville and Uganda child labor is highest in the middle wealth group. These findings seem to indicate that in these very poor African countries, the money brought in by working children is badly needed to pull households out of extreme poverty and help them to build up at least some wealth. In India, there are only small differences between the upper quintile and the rest. Hence, wealth does not seem to play a role of importance there.

4.1 Multivariate Analyses

Table 1 presents coefficients of the multivariate model. For factors that interact significantly with sex and/or living in an urban/rural area, separate coefficients are presented for boys and girls, urban and rural areas, or both. Coefficients that do not differ according to sex or urbanization are presented in column 1 (All), coefficients that differ according to sex in columns 2 and 3, those that differ according to urbanization in columns 4 and 5, and those that differ both according to sex and urbanization in columns 6–9. In three cases (occupation father non-farm, mother employed and proportion men in unskilled manual jobs) also the three-way interaction with sex and urbanization was significant.

Our analyses show that 60% of the variation in child labor is due to factors at the household level and 40% to factors at the context level. Resources at the household level influence the working status of children in several ways. As expected, children of fathers with more education work less. In rural areas, the education of the mother does not influence children’s work, but in urban areas, children with more educated mothers work less. Having a working mother is strongly related to employment of children. Mother’s employment increases the likelihood of children’s work, supporting the earlier finding (e.g. Francavilla and Gianelli 2007) that children with working mothers tend to work more. As this effect is controlled for household wealth, we cannot say that financial reasons are primarily responsible for this effect. Maybe these children work more because they go along with their mothers into the fields or factories. It is also possible that employment of the mother is a sign of demand for cheap female labor at the local labor market. Note that this effect is weaker for rural boys, suggesting that in the rural areas there is a greater division between women’s and men’s work. Children with fathers in upper nonfarm occupations are also less engaged in child labor. Rural girls are exceptions; they work significantly more if their father works in an upper nonfarm job. We do not have a straightforward explanation for this effect.

In line with expectations, we find that rural children living in wealthier families work significantly less than children in less well-off families. However, in urban areas children tend to work more if the family is richer. In these urban areas, the labor market structure must offer opportunities for child labor. Note that the wealth effect is a relative effect. Particularly in the poorest countries, being somewhat wealthier does not mean that a household has enough resources to free their children from child labor.

Many effects of structural demographic variables do not differ between boys and girls and rural and urban areas. Only the effect of age and of a missing father differs between boys and girls. Older children work more, yet this effect is stronger for boys than for girls. When the father is missing from the household, girls are more engaged in child labor. When the mother is missing, both boys and girls tend to work more. One would think that when the father is missing, boys have to take over the father’s role, but apparently single mothers tend to put economic responsibilities more on the shoulders of their daughters than of their sons. No evidence is found for the idea that parents favor their own children over foster children.

There is no difference between boys and girls with respect to birth order. Firstborn children work more than their later born siblings, suggesting that these children make money to pay for their sibling’s education. The significant positive quadratic term shows that this effect is nonlinear: for later born children the probability of working outside the household decreases slowly. Children with more brothers and sisters have to work more. This supports the resource-dilution argument. Whether the mother had her first child under the age of eighteen does not significantly influence the engagement in child labor of her children, nor does the age difference between partners. This might mean that cultural factors have a smaller influence on child labor than, for example, on educational participation, which tends to be reduced for children of teenage mothers (Huisman and Smits 2009).

4.2 Context Factors

Forty percent of the variation in child labor is explained by context level factors. This is relatively much, compared to what we know from research on educational achievement in Western countries, where Breen and Jonsson conclude that 80–90% of the variation is due to socio-economic factors at the household level (Breen and Jonsson 2005). With regard to context level resources, we see that children living in rural areas work more. The district level of development affects only the rural girls; if the district’s level of development is higher rural girls tend to work less. Interestingly, the availability of educational facilities, which is proxied by the mean years of male education in the district, does not have an effect. However, the effect of the labor market structure in rural areas is in line with expectations; the larger the proportion of men in unskilled (manual) labor, the more rural boys and girls are engaged in child labor. Hence, district level structural factors seem to affect child labor in rural areas by creating opportunities to work.

Both cultural context factors have a significant effect. In areas with a stronger position of males, indicated by a large age difference between partners, boys are less involved in child labor. In urban areas, children living in patriarchal families work more. It is possible that adult women work less in these areas and children fill in this labor force gap. This effect might not be present in rural areas because patriarchal kinship systems may differ between urban and rural areas. Kandiyoti (1988) for example argues that patriarchal kinships systems differ in the way women are treated. In rural areas in Africa, women are less affected by patriarchal traditional norms and are more involved in work outside the household, as opposed to women living in urban areas. Hence the effect of patriarchy might be only present in urban areas.

5 Conclusions

We tested a new multilevel theoretical framework to explain differences in child labor engagement and studied effects of household and context variables on the likelihood of being engaged in child labor for 239,120 children living in 18 developing countries. Our framework distinguishes three conditions, namely resources, structure and culture and does justice to the multilevel structure of children nested in districts in countries.

At the household-level, both socio-economic and family structure characteristics were included in the analysis. The context in which the household lived was indicated by its level of development, quality of the available educational facilities, patriarchy, the position of women, and urbanization. Besides direct effects of explanatory factors, also interactions with sex and urbanization were studied. In this way new insights were obtained into the role of the various determinants of child labor under different circumstances.

In line with expectations, we found resources at the household level to make a considerable difference for children’s employment. Most children work less if their parents have a higher educational level, if their father has an upper nonfarm occupation, and if the household is wealthier. The effect of employment of the mother is positive and stronger for girls than for boys. Hence, children and especially daughters of working mothers tend to work more. This finding is in line with earlier research (Bhalotra 2003; Francavilla and Gianelli 2007). Possible explanations are that girls tend to go along with their working mothers or that employment of mother’s is a sign of demand for cheap (female or children’s) labor at the local labor market.

Besides resource factors, characteristics of the family structure—reflecting in part an unequal distribution of resources and duties within the family—are associated with child labor. Children work more if they have more siblings and especially if they have more brothers. Hence the higher economic need of families with many children seems to push children into the labor market. Child labor is also higher in families with a missing mother. Our expectation that non-biological children would be more involved in child labor was however, not confirmed by the data. Neither do cultural factors at the household level influence child labor. If the mother had her first child at young age, or if there is a larger age difference between the parents, this does not influence children’s labor engagement significantly. Hence, recourses and structural factors seem to matter more than cultural factors.

We found less child labor in the urban areas. No significant effects were found for the other context factors: district level of development, quality of the local educational facilities and the position of women. That does, however, not imply that they are not important. Our interaction analysis revealed a substantial number of significant interactions between the context factors (including school quality and position of women) and sex and urbanization.

By testing interactions with gender and urbanization, we obtained more specific information on the importance of the risk factors for child labor under different circumstances and on the way their effects differ between boys and girls. With respect to gender, we found that both boys and girls work more when they grow older, but that this effect is stronger for boys. More importantly, we found the presence of a father to be especially important for girls. Whereas a missing mother increases the chances that both boys and girls work, a missing father only increases the employment probability of girls. Hence, single mothers seem to put economic responsibilities more on the shoulders of their daughters than of their sons. A cultural factor which is only significant for boys is the district’s mean age difference between spouses. If this difference is larger, meaning a more traditional environment, boys tend to do significantly less child labor. This finding is in line with the idea that in patriarchal areas families tend to invest more in sons.

Children in rural areas profit from living in a wealthier household; wealthier children tend to work less. Interestingly, in urban areas children tend to work significantly more if the household is wealthier. This effect might reflect the availability of more work opportunities in the cities (especially in unskilled labor intensive work), combined with the possibility that wealthier parents are better able to find work opportunities for their children (Nkamleu and Kielland 2006). Mother’s education is only important in urban areas; in rural areas children cannot profit from their mother’s resources.

Regarding the cultural context factors, we find that in areas with a weaker position of women boys tend to work less. However, in urban areas where more women marry into the families of their husbands, both boys and girls tend to work more.

Our central hypothesis regarding these interactions was that under more difficult circumstances the importance of socio-economic resources would be higher. This idea was largely disproved by our data. In urban areas, the effect of household wealth on child labor is positive. The influence of the other socio-economic factors did not differ between urban and rural. Rural girls are the exception; they seem to miss the boat in profiting from their father’s resources. Rural girls work more if their father has an upper nonfarm occupation. On the other hand, they are the only ones who profit from living in a more developed area. For policy makers, this finding is important. It shows that child labor reducing programs might have different and unexpected effects for different groups.

To conclude, our new theoretical model offers ample opportunities for comparative child labor research. If necessary, new indicators can be added to the model, and placed under one of the three conditions: resources, structure and culture. Moreover, the multilevel approach allows for studying the role of context factors and for testing whether effects of factors are different under different circumstances. We showed that they differ between urban and rural areas for 221 districts of eighteen developing countries, but this theoretical model and methodological approach can be applied to other geographical or research themes as well.

References

Allison, P. D. (2001). Missing data: Series/number 07-136. Quantitative applications in the social sciences. London: Sage University.

Barro, R. J. (1999). Determinants of democracy. Journal of Political Economy, 107(6), 158–183.

Baschieri, A., & Falkingham, J. (2006). Staying in school: Assessing the role of access, availability and opportunity cost. S3RI applications and policy working papers.

Bass, L. E. (2004). Child labor in sub-Saharan Africa. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Basu, K., & Van, P. H. (1998). The economics of child labor. The American Economic Review, 88(3), 412–426.

Basu, K., Das, S., & Dutta, B. (2007). Child labor and household wealth: Theory and empirical evidence of an inverted U. IZA discussion paper no. 2736.

Becker, G. S. (1993). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Beegle, K., Dehejia, R., & Gatti, R. (2004). Why should we care about child labor? The education, labor market, and health consequences of child labor. Working paper 10980. NBER working paper series.

Bhalotra, S. (2003). Child labour in Asia and Africa. Background research paper for the EFA monitoring report.

Bhalotra, S., & Heady, C. (2000). Child farm labor: Theory and evidence. STICERD—development economics papers 24.

Biggeri, M., Guarcello, L., Lyon, S., & Rosati, F. C. (2003). The puzzle of “idle” children: Neither in school nor performing economic activity: Evidence from six countries. Understanding children’s work project working paper series.

Bocolod, M. P., & Ranjan, P. (2008). Why children work, attend school, or stay idle: The roles of ability and household wealth. Economic Development and Culture Change, 56(4), 791–828.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: Towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society, 9(3), 275–305.

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223–243.

Buchmann, C. (2000). Family structure, parental perceptions, and child labor in Kenya: What factors determine who is enrolled in school? Social Forces, 78(4), 1349–1378.

Case, A. (2001). The primacy of education. WWS working paper 203. Princeton.

Chesnokova, T., & Vaithianathan, R. (2008). Lucky Last? Intra-sibling allocation of child labor. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 8(1) (Advances), Article 20.

Das, S., & Mukherjee, D. (2007). Role of women in schooling and child labour decision: The case of urban boys in India. Social Indicators Research, 82(3), 463–486.

Delap, E. (2001). Economic and cultural forces in the child labour debate: Evidence from urban Bangladesh. Journal of Development Studies, 37(4), 1–22.

Duryea, S., & Arends-Kuenning, M. (2003). School attendance, child labor and local labor market fluctuations in urban Brazil. World Development, 41(7), 1165–1178.

Dyson, T., & Moore, M. (1983). On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Population and Development Review, 9(1), 35–60.

Edmonds, E. V. (2006). Understanding sibling differences in child labor. Journal of Population Economics, 19(4), 795–821.

Edmonds, E. V. (2008). Child labor. In T. P. Schultz & J. Strauss (Eds.), Handbook of development economics (Vol. 4). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Emerson, P. M., & Souza, A. P. (2008). Birth order, child labor and school attendance in Brazil. World Development, 36(9), 1647–1664.

Fan, C. S. (2004). Relative wage, child labor, and human capital. Oxford Economic Papers, 56(4), 687–700.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (1998). The effect of household wealth on educational attainment: Demographic and health survey evidence. Policy research working paper series 1980. Washington: The World.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (1999). The effect of household wealth on educational attainment: Evidence from 35 countries. Population and Development Review, 25(1), 85–120.

Francavilla, F., & Gianelli, G. C. (2007). The relationship between Child Labour and mother’s work: The case of India. IZA discussion paper series, no. 3099.

Global March Against Child Labor. (2011). Worst forms of child labour country report 2005. Accessed January 20, 2011. http://www.globalmarch.org/worstformsreport/world/.

Grootaert, C., & Kanbur, R. (1995). Child labour: An economic perspective. International Labour Review, 134(2), 1–18.

Gündüz Hoşgör, A., & Smits, J. (2008). Variation in labor market participation of married women in Turkey. Women’s Studies International Forum, 31, 104–117.

Handa, S. (2002). Raising primary school enrolment in developing countries: The relative importance of supply and demand. Journal of Development Economics, 69, 103–128.

Hijab, N. (2001). Women and work in the Arab world. In S. Suad & S. Slyomovics (Eds.), Women and power in the Middle East (pp. 41–51). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Hindman, H. D. (2009). The world of child labor: An historical and regional survey. New York: M. E. Sharpe.

Hobcraft, J. (1993). Women’s education, child welfare and child survival: A review of the evidence. Health Transition Review, 3(2), 9–173.

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. New York: Erlbaum.

Huisman, J., & Smits, J. (2009). Effects of household and district-level factors on primary school enrollment in 30 developing countries. World Development, 37(1), 179–193.

ILO-IPEC. (2006a). Minors out of mining! Partnership for global action against child labour in small-scale mining. Geneva: ILO-IPEC.

ILO-IPEC. (2006b). The end of child labour: Within reach. Global report under the follow-up to the ILO declaration on fundamental principals and rights at work. Geneva: ILO-IPEC.

ILO-IPEC. (2008). Global child labour developments: Measuring trends from 2004 to 2008. Geneva: ILO-IPEC.

ILO-IPEC. (2010). Accelerating action against child labour. Global report under the follow-up to the ILO declaration on fundamental principles and rights at work. Geneva: ILO-IPEC.

Kambhampati, U., & Rajan, R. (2008). The ‘nowhere’ children: Patriarchy and the role of girls in India’s rural economy. The Journal of Development Studies, 44(9), 1309–1341.

Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with patriarchy. Gender & Society, 2(3), 274–290.

Kis-Katos, K., & Schulze, G. G. (2006). Where child labor supply finds its demand. University of Freiburg, Institute for Economic Research, working paper.

Kondylis, F., & Manacorda, M. (2006). School proximity and child labor. Evidence from rural Tanzania. Working paper for the UCW access and quality workshop.

Kurosaki, T., Ito, S., Fuwa, N., Kubo, K., & Sawada, Y. (2006). Child labor and school enrollment in rural India: Whose education matters? The Developing Economies, 44(4), 440–464.

Levy, V. (1985). Cropping pattern, mechanization, child labor, and fertility behavior in a farming economy: Rural Egypt. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 33(4), 777–791.

Lieten, G. K. (2003). The causes for child labour in India: The poverty analysis. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 45(3), 451–464.

López-Calva, L. F. (2002). A social stigma model of child labor. Estudios Economicos, 17(2), 193–217.

Maitra, P., Panda, B., & Sarangi, S. (2006). Idle child: The household’s buffer. Working paper.

Manacorda, M., & Rosati, F. C. (2007). Local labor demand and child labor. Conference paper for IZA conference.

Mugisha, F. (2006). School enrollment among urban non-slum, slum and rural children in Kenya: Is the urban advantage eroding? International Journal of Educational Development, 26(5), 471–482.

Mukherjee, D., & Das, S. (2008). Role of parental education in schooling and child labour decision: Urban India in the last decade. Social Indicators Research, 89(2), 305–322.

Nardinelli, C. (1980). Child labor and the factory acts. The Journal of Economic History, 40(4), 739–755.

Nieuwenhuys, O. (1994). Children’s lifeworlds. Gender, welfare and labour in the developing world. London: Routledge.

Nkamleu, G. B., & Kielland, A. (2006). Modeling farmer’s decisions on child labor and schooling in the cocoa sector: A multinomial logit analysis in Côte d’Ivoire. Agricultural Economics, 35(3), 319–333.

Patrinos, H. A., & Psacharopoulos, G. (1997). Family size, schooling and child labor in Peru: An empirical analysis. Journal of Population Economics, 10(4), 387–405.

Ranjan, P. (1999). An economic analysis of child labor. Economics Letters, 64(1), 99–105.

Self, S., & Grabowski, R. (2009). Agricultural technology and child labor: Evidence from India. Agricultural Economics, 40(1), 67–78.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smits, J. (2007). Family background and context effects on educational participation in five Arab countries. Nijmegen Center for Economics (NiCE), working paper 07-106.

Smits, J., & Gündüz Hoşgör, A. (2006). Effects of family background characteristics on educational participation in Turkey. International Journal of Educational Development, 26(5), 545–560.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. A. J. (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage.

Spierings, N., Smits, J., & Verloo, M. (2010). Micro and macro level determinants of women’s employment in six MENA countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1391–1407.

Sundaram, A., & Vanneman, R. (2008). Gender differentials in literacy in India: The intriguing relationship with women’s labor force participation. World Development, 36(1), 128–143.

UNICEF. (2008). Child labour and school attendance: Evidence from MICS to DHS surveys. New York, USA: UNICEF.

Webbink, E., Smits, J., & de Jong, E. (2011). Hidden child labor: Determinants of housework and family business work in 16 developing countries. World Development. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.005.

World Bank. (2002). Poverty reduction strategy paper. Education chapter. Geneva: World Bank.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Webbink, E., Smits, J. & de Jong, E. Household and Context Determinants of Child Labor in 221 Districts of 18 Developing Countries. Soc Indic Res 110, 819–836 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9960-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9960-0