Abstract

This paper discusses the relations between economic development, family income, and happiness in post-communist Poland from the point of view of Inglehart’s theory of modernization. The happiness is understood as satisfaction with income and life, and as psychological well-being. The analysis of survey data yields the conclusion that economic development reduces the strength of the relations between income and satisfaction as well as between income and psychological well-being. These findings may be explained by changes in the value system from collectivist/materialist to individualist/post-materialist, even when these values are not directly measured. The analyzed data are from a series of representative surveys conducted in Poland during a period of political and economic transformation (i.e., between 1989 and 2008). Official statistical data on Polish economic development during the same period are used as a background for survey results. The relations between income and happiness change in Poland in a way consistent with Inglehart’s modernization theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Happiness, Satisfaction, and Psychological Well-Being in Time of Modernization: Theoretical and Conceptual Background

Modernization is currently understood as a complex process consisting of such intertwined elements as economic development, change in value system from materialist (subsistence) to post-materialist values (concerning independent personal development and free self-expression), and democratization of a political system. The values are assumed to constitute an intermediate factor, or—to use empiricist terminology—the intervening variables between economic developments and rising material standards of living on the one hand and democratization, legitimization, and consolidation of democratic institutions on the other (Inglehart and Welzel 2007). What would be the ultimate aim of such modernization, or the criteria of its evaluation? One has to agree with Inglehart and Welzel that the changes taking place in social values and in democratic institutions shift the weight from the so called common (public, collective, social, national, group, or class) good and interests, social discipline, and conformism necessary to achieve them, toward individual freedom, autonomy, diversity, unrestricted individual development, and self-expression. However, the question remains, where should all of these lead us? It may be declared that the ultimate effects of modernization should be such living conditions, broadly understood, that are consistent with peoples’ aspirations and needs shaped by their changing value systems. Such a consistency should increase individuals’ satisfaction or happiness; a concept discussed by philosophers (from old Greeks such as Aristotle 1986; Plato 1892 to Bentham 1969; Tatarkiewicz 1976; Russel 1975; Hayborn 2000; Gadacz 2008) as well as empirical social scientists (e.g., Veenhoven 1989a, b, 2005; Frey and Stutzer 2002; Van Praag and Carbonell 2008; Petersen et al. 2005; Koralewicz and Zagórski 2009).Footnote 1

Veenhoven and other researchers often use the terms happiness and life satisfaction interchangeably. Happiness is understood as a subjective and emotional positive evaluation of one’s’ own life. Thus, it has a somewhat different meaning than quality of life or psychological well-being. The question “How are you satisfied with your life as a whole?” is often used in sociological and psychological research as a measurement tool consistent with such understanding. The level of life satisfaction is typically measured on interval scale from very dissatisfied to very satisfied with several intermediate categories such as somewhat (rather) dissatisfied, somewhat (rather) satisfied, etc. Respondents are sometimes asked to mark the level of their satisfaction on an eleven, ten, or seven-point scale presented as a horizontal line or ladder. Sometimes the composite index of life satisfaction is constructed as an unweighted or weighted mean satisfaction with various realms of life, such as family, work, material conditions, health, education, etc. Veenhoven seems to be right that measurements based on one general question are often better than composite indices combining several realms. While a single question is more prone to measurement error, it allows the investigation of relations between general life satisfaction and satisfaction with various components of life. Satisfaction is sometimes even reduced to a dichotomous variable of satisfied or dissatisfied for broad international comparisons (Europejski Sondaż Społeczny 2006) or for calculation of other indexes, such as the duration of a happy life (Veenhoven 2005). Thus, the dichotomous measures of satisfaction with life and with its material conditions are used in dynamic analyses presented in this article. A more detailed interval satisfaction scales are later used in determination models.

A very general concept of happiness, embracing three elements: life satisfaction, material or income satisfaction, and psychological well-being are applied here. This is, of course, a purely conventional matter and we do not deny the usefulness of either less or more general concepts of happiness.

Assumptions of changes from traditional to rational values and then from materialist (survival) to postmaterialist (self-expression) values constitute the core of modernization theory elaborated and empirically proved by Inglehart and Welzel (2007). This contradiction, or continuum, of social values is consistent with Maslow’s (1962; 1964) distinction of basic needs, created by deficiencies, and higher needs for development, also called the needs of growth and being. Most important of the latter are one’s self-realization needs, understood by Maslow in a way similar Inglehart’s understanding of self-expression needs and values. According to Maslow, the feeling of such higher needs and one’s ability to satisfy them constitutes a necessary condition of psychological well-being resulting in improved living conditions and progress in general. Thus, there are apparent similarities between Inglehart’s theory of modernization and Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of human needs. Other links are apparent between Inglehart’s concept of modernization and the concept of post modernity (Anderson 1998; Bauman 2000), that allow to paradoxically call Inglehart’s theory a theory of postmodern modernization.

It is commonly known that strong relations between material living conditions and satisfaction with such conditions and with life in general are curvilinear. In other words, the higher the material level of living, the less it affects the satisfaction. Economists were first to understand this, so they routinely use logarithms of income rather than its absolute values in econometric models. Sociologists have more recently gained this understanding. The curvilinearity of the relations between material conditions and satisfactions was recently documented in the Polish society (Koralewicz and Zagórski 2009; Zagórski 2009).

While nobody disputes the existence of a strong relation between material conditions and peoples’ satisfactions on the individual level, the prevailing long-time opinion has been that there are no such relations on the aggregate (national) level. Early comparative analyses have indicated no apparent relations between level of economic development and average life satisfaction or material satisfaction measured at national level (Easterlin 1974, 1995; for the discussion see Zagórski et al. 2010). Citizens of wealthier and more developed countries were reportedly, on the average, no more satisfied with their life than citizens of poorer and less developed countries were. A similar lack of correlation between changing economic conditions and happiness was also found in dynamic analyses (Easterlin 1995; Frey and Stutzer 2002); however, both statements can be disputed.

Frey and Stutzer, who have analyzed the growing gap between rising GDP and temporarily falling then stabilized levels of life satisfaction in the USA, have overlooked or neglected the fact that both were changing parallel to each other until the late 1950s. This raises the question concerning what occurred from the end of the 1950s to the late 1960s that negatively influenced the mood of Americans irrespective of economic growth and divorced one from the other. Such events and processes could have played a role in this change as the Vietnam war, the beginning of alternative culture movements, racial tensions and the growing activity of African Americans, the assassinations of John. F. Kennedy and Luther M. King, the beginning of student protests, and the spreading consciousness that economic growth is not equivalent to social development. These factors produced shock to American society, which could have lead to the disparity between the economic growth and general life satisfaction. Taken together with the rising level of living, these factors could also have lead to the growing importance of post-materialist values. The hypothesis seems to be quite strong, in light of this historical background, that the changing value system contributed to the growing gap between material situation and happiness seen today in the US; the latter being determined more by non-material or post-material realms of life. However, this was not always the case.

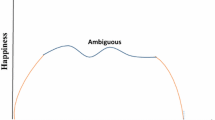

As far as cross-country rather than dynamic analyses are concerned, the supposed lack of correlation between levels of economic development and satisfaction, suggested by early research, may be explained by the fact that only relatively wealthy and developed Western countries were subjects of early analyzes. By analyzing satisfaction levels of both wealthy and poor individuals, researchers can draw conclusive assumptions of the differences in life satisfaction within and between these groups. Accordingly, findings have been weak or nonexistent, when the aggregate level analyzes concerned only wealthy societies. The analyzes have brought quite different results when poorer countries from Latin America, Africa, Asia, and East Europe were also considered in the research. Specifically, it become apparent that the more economically developed a country, the higher citizens’ life satisfaction was. However, this relation is curvilinear and similar to that established at the individual level; it is quite strong at low levels of economic development and almost non-existent at high levels. In other words, the higher the level of economic development and wealth of a country, the weaker its impact on reported satisfaction (Frey and Stutzer 2002; Schyns 2002; Veenhoven 1997, 2005). The typical, generalized relation on both the individual and national level is presented in Fig. 1.

Moreover, the analyzes indicate that people from wealthy countries are more satisfied with their material conditions or life in general, and that this satisfaction depends on objective conditions significantly more so in poor compared to wealthy societies (Schyns 2002). Poor people are usually more satisfied in wealthy societies than they are in poor societies, while wealthy people are happier in poor societies than in rich societies. These relations concern not only material conditions, but also other realms, such as education, health, and work (Zagórski et al. 2005, 2010). The typical curves for poor and wealth countries are depicted in Fig. 2.

To generalize earlier evidence from international comparisons, one can say that the more common particular goods are—income in this case—in a society, the weaker their impact on subjective satisfaction with life and with these goods (see also Graham and Pettinato 2002). Such an assumption constitutes the theoretical base of the construction of inversely proportional indices of wealth and life satisfaction. The values of particular goods, material and other, which constitute components of such composite indices, are inversely proportional to the percentages of people who have these goods in a given society (Zagórski 2005, 2008).

All these assumptions and the findings supporting them are consistent with such classical theories as Maslow’s (1962, 1964) hierarchy of human needs, reference groups theory (Merton 1957; Hyman and Singer 1968), theory of discretional consumer behavior (Katona 1964), theory of elite and mass consumption, and conspicuous consumption (Veblen 1994). The diminishing impact of material living conditions on life satisfaction at higher levels of wealth can be explained in terms of reference groups and with relative advantage/disadvantage theories.Footnote 2 In this paper; however, the problems of satisfaction with life and with material living conditions will be located in a broader theoretical framework of modernization and postmodernization (Inglehart 1990, 1997; Inglehart and Welzel 2007).

Inglehart’s theory, which is based on dynamic, comparative analyzes of empirical data from many countries, concludes that the importance of material (survival) needs, diminishes in the course of human and social development. Likewise, post material needs of a higher order, especially those concerning self-realization and self-expression, assume more subjective importance for the individual and spread throughout society. This change in value system constitutes the outcome of economic development, in a course of which the material needs are more regularly satisfied. While life satisfaction depends to a great extend on a full belly and a roof over one’s head in underdeveloped societies, the satisfaction of such needs and further accumulation of material goods do not increase the feeling of happiness in most developed societies, where other needs become more important. The same can be said on the individual level. Wealthy people pay less attention to satisfaction of basic material needs compared to poor people. As a consequence, the same increment in material level of living offers the poor more satisfaction than it offers the wealthy. It can be reasonably assumed that this regularity applies to satisfaction with income, life, and to psychological well-being (i.e., all three elements of our concept of happiness).

2 Happiness and Changes in Polish Society—Research Problem

The relations between happiness and material conditions were examined until recently more often comparatively than dynamically. However, modernizing processes take place in time and there is no dispute that dynamic analyzes do not always yield the same results as cross-sectional analyses. Inglehart and Welzel have conducted both cross-country and dynamic analyzes; however, they did not place much emphasis on the relations between material conditions and happiness. Polish data allow to conduct dynamic analyzes of these relations. The research question posed in this article focuses on how modernization of Poland, especially Polish economy, and resulting improvement in material conditions influence the relations between these conditions and satisfaction with them, with life in general, and with psychological well-being. The hypothesis stemming from previous evidence, and theories discussed above, states that material improvements influence the happiness stronger at initial than at later stages of development. If this is the case, findings should be regarded as consistent with Inglehart’s scheme of human development.

Twenty years ago, changes to Poland’s political and economic system were enthusiastically supported by an overwhelming majority of the society. They instigated initial euphoria, which was quickly replaced by a bitter disillusionment caused by unexpected negative side effects of transformation. Subsequent normalization and economic improvement have resulted in gradual increase in satisfaction. The following section is devoted to examining whether the dynamics and the directions of these processes were consistent with the regularities discussed in the conceptual-theoretical section above. Though the analyzes do not directly concern the changing value system of the Polish society, the hypothsis concerning such changes is useful in interpreting the results. Thus, the problems of happiness can be viewed in a broader context of socioeconomic modernization, as understood by Inglehart and his followers.

3 Economic Development, Income, and Satisfaction—Description of Changes

A description of the changing situation in Poland is needed prior to an analysis of the relations between such aspects of this situation as objective living conditions and subjective reactions to them. The best reference year for assessing the changes is 1994, when the trend of declining incomes of the population reversed. Moreover, this is the first year for which fully comparable data on the evaluation of family income and satisfaction with various realms of life exist. Whenever possible, however, the changes since 1989 (i.e., since the beginning of radical economic and political transformation) will be described.

The national income (GDP) started to deteriorate in Poland many years before the political and economic transformation in 1989. The demise of the centrally planed state economy and the introduction of free market mechanisms did not reverse that trend for some time. Moreover, the economic transformation caused at its initial stage the bankruptcies of many unprofitable state owned enterprises and resulted in growing unemployment. GDP began to grow again as early as 1992 when the so called Balcerowicz’s (1994) shock therapy started to work, irrespective of being halted (albeit not reversed) by his successors in the government. However, the average family income fell in comparison until 1994. Thus, the economic recovery has resulted in the rise of the population’s income with about a three-year delay. This, however, was associated with growing inequality, which we cannot analyze here.

Some irregularities in the trend of growing income, depicted by Fig. 3, were most probably caused, to some extent at least, by measurement errors since data are based on respondents’ declarations during representative sociological surveys. Irrespective of a well-known tendency of respondents to underestimate their income or not to provide honest answers, the people face real difficulties when estimating their income in response to one survey question, especially if this question concerns per capita family income (see Zagórski 2009). While all that may have substantially lower the level of declared income, this flaw may have weaker impact on investigated trends and relations. Overall, the average disposable income per capita has grown in Poland quicker than the economy in general.

The question has to be asked, whether income satisfaction grew at the pace similar to the growing economy and real income (Fig. 4).

Changes in GDPa and per capita family incomeb in Poland, 1989–2008. (1994 = 100). a Author’s calculations based on GUS (Central Statistica Office) data published in Statistical Yearbooks for respective years. b Author’s calculations in 1994 fixed prices, based on GUS (Central Statistica Office) data on inflation and CBOS (Public Opinion Research Center) data on income

Changes in GDPa, per capita family incomeb, and satisfaction with income as well as with incomec in Poland, 1989–2008 (1994 = 100). a Author’s calculations based on GUS (Central Statistica Office) data published in Statistical Yearbooks for respective years. b Author’s calculations in 1994 fixed prices, based on GUS (Central Statistica Office) data on inflation and CBOS (Public Opinion Research Center) data on income. c Author’s calculations based on CBOS representative surveys. Percent of people very satisfied and satisfied in 1994 = 100.0

Changes in GDPa and psychological well-beingb in Poland, 1989–2008 (1994 = 100). a Author’s calculations based on GUS (Central Statistica Office) data published in Statistical Yearbooks for respective years. b Author’s calculations based on CBOS representative surveys. Percent of people in good psychological condition in 1994 = 100

Poles are not very satisfied with their incomes. However, the proportion of those satisfied has increased from less than one tenth, in 1994, to more than one fourth in 2008. Despite such a large increase, the people dissatisfied with income still outnumber those satisfied and those expressing ambivalent feelings.

Satisfaction with life in general was much higher than income satisfaction and also grew quite rapidly, from 54.1%, in 1994, to 70.5%, in 2008. This represents an incremental growth of about 15%, similar to that concerning income satisfaction. The rate of growth of income satisfaction was, however, much higher because of a much lower departure point (Tables 1, 2).

Further dynamic analyzes should consider relative changes. As already stated, 1994 is the best base year for comparing the economic growth to the changes in disposable incomes, life satisfaction, and income satisfaction. Thus, the values of GDP and family per capita income, as well as the percentages of people satisfied with income and with life in general are set for this purpose at 100.0 for 1994.

The analysis indicates that personal satisfactions are changing at quite different paces than objective macro and micro-economic indicators. The percentage of people satisfied with their family income is growing much more rapidly than both the actual income level and the GDP. Percentage of those satisfied with their life in general is also growing; however, at a much slower pace. The average family per capita income and GDP were almost two times higher in 2008 than they were in 1994, while income satisfaction was almost three times higher and life satisfaction only about one quarter higher.

Despite the differences in the pace of changes, the correlations between values of GDP, family income, satisfaction with income, and life satisfaction are quite high, especially when years are used as aggregate observation units (see Pearson’s coefficients below the diagonal of Table 3). The time since the beginning of the transformation, measured as years after 1989, is almost perfectly correlated with GDP and satisfaction with both life and income. The correlations with income are only slightly lower and should still be considered extremely high. The lowest correlation measured on an aggregate (year) level was between family income and life satisfaction, but even this was as high as .85.

Correlations between the same variables on the individual level are much lower, albeit statistically significant due to the large size of the pooled sample. Regression models on the individual rather than the aggregate level should shed more light on determining satisfaction with income and life.

4 Economic Development and Psychological Conditions—Descriptive Analysis

One can assume that objective material conditions, as well as satisfaction with them and with life as a whole, are strongly associated with psychological well-being. If modernization, especially its economic component, improves living conditions and satisfaction with various realms of life, modernization should also contribute to psychological well-being.

CBOS surveys have investigated psychological condition annually using a short psychological test consisting of nine questions on the frequency of feelings of various positive and negative emotions. The four positive emotions include satisfaction with something that went well, conviction that everything is good, pride with one’s own achievements and interest in something new or intriguing. The five negative emotions include feeling of nervousness, weariness or boredom, unhappiness, helplessness, and anger (see Wciórka 2005; Koralewicz and Zagórski 2009). The response options constitute a four level interval scale: very often, often, rarely, never, or almost never. Responses are assigned values 4–1 with respect to positive emotions and from 1 to 4 with respect to negative emotions. People in good psychological condition are defined as those whose average on these four scale exceeds the middle point (i.e., is greater than 2.5).

The fraction of the population in good psychological condition increased at a pace similar to GDP growth (Fig. 5). The question remains, how correlations between level of economic development, material living conditions, and psychological well-being are changing during this modernization period. Similar to the hypotheses on satisfaction with life and with material conditions, one can expect that improving material conditions would weaken the correlation between income and psychological well-being.

5 Modernization and Determinants of Satisfaction and Psychological Well-Being

5.1 Dynamic Analysis

The impact exerted by income and modernization on satisfaction with income and life, as well as on psychological well-being was assessed by regression equations. The list of determinants in the model included variables commonly known to influence happiness, such as gender; age (plus its quadratic term); education measured by typical number of years necessary to achieve a declared level; and per capita family income (also with its quadratic term). It was impossible to include both time of transformation and GDP in the same regression model because of the almost perfect correlation between these variables. The replacement of one by the other would not change the results. The time of transformation (years since 1989) was used as a measure of the development, because this variable can be interpreted as reflecting a wide array of different social, political, and economic aspects of modernization, rather than just the economic factor. A variable indispensable for the dynamic analysis, namely the interaction between family income and time (advancement) of transformation was also included in the model. The patterns of determination of satisfaction with income and with life are presented in Table 4.

Influence exerted by gender on both income satisfaction and life satisfaction, net of other independent variables, was almost negligible albeit statistically significant due to the large sample size. Interestingly, findings reveal that men are in much better psychological condition than women with the same characteristics and same economic situation.

The data confirm a well-known fact that satisfaction and psychological well-being deteriorate with age, though this is a curvilinear relation. Both the youngest and the oldest people are somewhat more satisfied and feel less psychological stress than mid-aged ones.

The net effect of education is higher on life satisfaction and psychological well-being than on income satisfaction, which is much more dependent on family income.

Family per capita income exerts a strong positive effect on all three aspects of happiness, the strongest on income satisfaction, and the weakest on life satisfaction. The coefficients for the quadratic term of income indicate consistency with our theoretical expectations. All three effects of income are curvilinear. The wealthier the person, the less impact is exerted on their happiness by the same increment in family income.

Regression models confirm the result of descriptive analyzes indicating that all three aspects of happiness increased with the modernization of Poland. Moreover, the models indicate that the modernization process reduces, though does not cancel, the impact of income exerted on income satisfaction and psychological well-being. (The time/income interaction term’s coefficient for life satisfaction is also negative, showing the same tendency, but it is statistically insignificant).

The consistency of general tendencies with our assumptions becomes more apparent when two separate regression estimations are made for two distant years, namely 1994 (the lowest point of departure) and 2008 (the highest point of transformation).

As seen, the slope is steeper for 1994 than for 2008 (Fig. 6). Thus, modernization processes (stabilization of democracy, economic development, and improvement of living conditions) reduced the dependency of life satisfaction on income. Moreover, the relation between these variable is curvilinear, disappearing on high income levels. However, one reservation has to be made. The vertical dimension ranges only from 3.5 to 4.5 satisfaction points on the graph, while the full range of life satisfaction was actually from 1 to 5. Thus, the depicted relation between income and life satisfaction is quite weak.

Regression models explain income satisfaction and psychological well-being more effectively than they explain life satisfaction. Since psychological well-being is best explained statistically, its determination is presented in Fig. 7. Modernization of Poland, measured by years of transformation processes, reduces the dependency of psychological well-being on income. Moreover, the range of change in well-being is much wider than the range of change in life satisfaction.

5.2 Cross-Section (Regional) Analysis

Most of the data analyzed so far came from typical representative surveys. Typical (relatively small) samples of such surveys allow researchers to conduct analyzes at the individual level or to compare the data for the whole countries. The unusually large representative sample used in the research project “Living Conditions of Polish Society: Problems and Strategies,” conducted in 2007 in Poland (Zagórski and Grabowska 2009), have allowed the aggregate data analyses below the national level. Available individual data can be aggregated into voivodships (the largest Polish units of regional administrative division), metropolitan regions,Footnote 3 and gminas (the smallest units of this division).Footnote 4 Thus, the comparison of sub-national regions of different levels of administrative division and richness was possible (Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11).

Polish gminas usually consist of a small town and a few surrounding villages. However, some gminas have a purely rural character, while some other are purely urban and consist only of one middle size town. Their size makes the gminas close to the sociological concept of local communities. Voivodships are much larger and there are sixteen in Poland. They consist of one or a few large cities and surrounding gminas. Metropolitan regions (or rather future metropolises) constitute much more natural and comprehensive entities than voivodships. People may more often identify themselves with the metropolitan region than with voivodship.

Satisfaction with material living conditions and with life are measured here on a five-point interval scale from “very dissatisfied” (−2), through intermediate answers (valued as −1, 0, +1), to “very satisfied” (+2). Equivalent income received by households is calculated, taking into account household economy of scale, according to the method used by OECD and EU statistical offices.Footnote 5 Equivalent income is much better than per capita income as a measure of family material situation.

The regression model takes the form:

where x = mean satisfaction in voivodship, a = constant, y = mean equivalent income in voivodship, Y = mean equivalent income in all voivodships, b and c = regression coefficients.

Life satisfaction is much higher than satisfaction with material living conditions. Both kinds of satisfaction have curvilinear relation to income, material satisfaction being—of course—more dependent on it. Both satisfactions grow fast between low-income groups, stop growing at an income level of about 1,500 zł (i.e., a bit higher than the average), and show a tendency to decline at the highest income levels. Thus, the relations uncovered on the aggregate level of Polish voivodships are fully consistent with earlier evidence and theoretical generalizations concerning the different countries or individuals from one country.

It must be noted that voivodships are somewhat artificially delimitated for administrative purposes. As stated, potential metropolitan areas constitute more internally integrated units. Since only eight such areas were delimitated in Poland for the purpose of the current research, the regression models are not calculated for them.

Metropolitan regions show the same pattern of relations between income and satisfaction as the voivodships (see Fig. 10). The populations of two poorest regions, Lublin and Łódź, were the least satisfied both with their material situation and with their whole life. Life satisfaction was highest in mid-income metropolises: Cracow, Gdańsk-Gdynia, Katowice (Silesia), and Poznań. The metropolitan region of Poznań occupies also the highest position with respect to material satisfaction. The inhabitants of the two wealthiest metropolises, Wrocław and Warsaw, are slightly less satisfied with their life than inhabitants of the four middle-income cities; however, they are more satisfied than those from two poorest metropolitan areas. They are also less satisfied with material conditions than inhabitants of a bit poorer Poznan. Since all metropolitan regions are dominated by urban population of big cities, the differences in material and life satisfaction are small between them, but the curvilinearity of satisfaction dependency on income is apparent, especially in a case of life satisfaction.

As stated, gminas constitute administrative units that are much smaller than voivodships and metropolitan areas and, thus, much closer to real local communities. The regression model applied for gminas was the same as that used for voivodships. However, the results are not as clear as they are on a higher aggregation level.

There is an apparent positive correlation between income and life satisfaction. The curvilinearity of this relation is consistent with previous findings and theoretical expectations, but almost negligible. Moreover, the regression line is not very steep, indicating a week correlation. The results for satisfaction with material conditions, not presented here for the sake of simplicity, are even less concluding. Of course, the correlation between income and material satisfaction is positive. The regression line is steeper than for life satisfaction. However, its curvilirearity is in a direction opposite to the expectations and to those established for voivodships and metropolies.

There are four possible explanations of the inconclusive results for gminas. First, gminas do not include large cities, thus their average incomes are much lower than those of voivodships (Zagórski 2009), which could have affected some relations. Second, people in gminas may evaluate their situation relative not to their neighbors, but to those in larger towns outside the gmina. Third, the sample sizes in gminas ranged from about 150 to 1,000 respondents. Thus, the statistical error was much greater in smallest gminas than in the 16 samples of voivodship populations, each one of about 2,000 respondents. Fourth, while all voivodships were surveyed, only 65 gminas were selected from more than 2,500 existing ones. The selection was not exactly representative, since the original purpose was to choose different types of localities for case studies rather than for statistical analyzes of their entire spectrum. Despite these reservations, the results for gminas, though not very apparent, are consistent with the results for much larger voivodships and metropolitan regions with respect to life satisfaction and were partly consistent with respect to satisfaction with material conditions.

6 Conclusions

The decay and consecutive demise of the state socialism and centrally planned economy in Poland have caused the decline of GDP, disposable family income, and dissatisfaction with material conditions and with life in general. These negative trends continued during the initial stage of transformation; however, they reversed in the 1990 s. The ongoing, though not always systematic, improvement in the realms of economy, social life, and psychological conditions of Poles has been apparent since then.

Earlier sociological research and theory, discussed in the introduction of this paper, have strongly suggested that socioeconomic modernization, especially in the post-modern period, involves (or results in) diminishing importance of material needs as well as material values (called also subsistence values), and a growing importance of post-material needs and post-material values, especially self-expression values. This led to the hypothesis that material living conditions, especially incomes, are losing their importance as determinants of happiness, which becomes more dependant on non-material gratifications. Of course, it does not mean that material conditions have become completely irrelevant; their impact on happiness has only diminished not disappeared.

The Polish data analyzed in this paper indicates that systemic transformation from state socialism to a free market democracy, after a short initial period, instigated economic growth and improvement in average material living conditions. This has resulted in growing satisfaction with income, material conditions, and life in general, as well as improvement in the psychological conditions of the people. Since these processes have taken place alongside structural and organizational changes in economy and politics, they can be considered, together, as elements of modernization.

The diminishing importance of material conditions for happiness, documented here by dynamic and cross-region analyses, can be explained by the assumed changes in value systems in a direction consistent with modernization theory [i.e., from materialist (subsistence) values to post-materialist (self-realization) values]. As Veenhoven (1997) documented, wealthy societies are characterized by positive correlations between life satisfaction, individualistic value systems typical for post-modern societies, objective possibilities, and personal capabilities to satisfy individualistic needs, even though these correlations were not significant or negative in poor nations. This may be interpreted in times of gaining subjective significance by post-material needs in terms of economic development and rising material living conditions. The analyses presented in this paper suggest that, irrespective of whether the assumed changes in Polish social values are seen as an element of modernization or as its consequence, their direction is consistent with changes that took place in other modernizing societies, including the most developed ones. This is further confirmed by cross-sectional analyses concerning Polish regions and local communities of different levels of economic development.

Since the post-communist transformation and modernization period is relatively short, the above-mentioned processes are less apparent than they would have been in a longer time. However, the findings of the current study can be seen both as optimistic and consistent with internationally discovered trends and theoretical assumptions.

Two reservations have to be made here. First, the current analysis concerned the average situation and average happiness of the total or regional populations. Other research, not discussed here, indicate that inequalities have increased in Poland during the transformation period, though it appears that they have not increased significantly during last years and perhaps they have recently begun diminish. The changing inequalities may have influenced and even blurred the interrelations found in the current study. Thus, further analyzes of determinants of happiness certainly must take into account various dimensions of social inequality. Second, the data at our disposal did not cover the years of the latest financial crisis. Though this crisis influenced the Polish economy much less than the economies of almost all other European countries, its impact on subjective feelings is unknown. One cannot be certain that all regularities and changes discussed in this paper are irreversible.

Notes

For a comprehensive discussion and more bibliographical data see Sirgy (2002).

For more discussion see: Zagórski (2005), Zagórski et al. (2010).

Since no Polish urban agglomeration fits the criteria used by regional scientists to define metropolises, this term has to be used here with reservation. It would be better to speak about future or potential metropolitan regions. These regions have been delimitated by EUROREG, the University of Warsaw (Hryniewicz et al. 2008; Jałowiecki 2009).

National representative stratified random sample of 38,866 respondents was sufficient to analyze aggregate data for each of existing 16 voivodships. Separate, though much smaller representative stratified random samples for each of the 65 chosen gminas (27,745 respondents) provided good aggregate data as well.

References

Anderson, P. (1998). The origin of postmodernity. London: Verso.

Aristotle, (1986). Nicomachean ethics. New York: Holt, Rinahart & Winston.

Balcerowicz, L. (1994). Understanding post-communist transitions. Journal of Democracy, 5(4), 75–89. doi:10.1353/jod.1994.0053.

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Bentham, J. (1969). An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. In M. P. Mack (Ed.), A Bentham reader (pp. 72–144). New York: Pegasus.

Czapiński, J., & Tadeusz, P. (Eds.). (2007). Diagnoza społeczna 2007—Warunki i jakość życia Polaków [social/diagnosis 2007—conditions and quality of life of poles]. Warszawa: Wizja Press & IT.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). New York: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization, 27, 35–48. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-B.

Europejski Sondaż Społeczny. (2006). European social survey. Warszawa: IFiS PAN.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness & economics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gadacz, T. (2008). O ulotności życia. [On Transient Life]. Warszawa: Iskry.

Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2002). Happiness and hardship—opportunity and insecurity in new market economies. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Hayborn, D. M. (2000). Two philosophical problems in the study of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 207–225. doi:10.1023/A:1010075527517.

Hryniewicz, J., Jałowiecki, B., & Tucholska, A. (2008). Jak się żyje w przyszłych metropoliach? [How do people live in future metropolies] Opinie i Diagnozy, 10. Warsaw: CBOS.

Hyman, H. H., & Singer, E. (Eds.). (1968). Readers in reference group theory and research. New York: Free Press.

Inglehart, R. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2007). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy—the human development sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jałowiecki, B. (2009). Warunki życia w metropoliach i ich otoczeniu [Living conditions in metropolies and their surroundings]. In K. Zagórski, G. Gorzelak, & B. Jałowiecki (Eds.), Zróżnicowania warunków życia. Polskie rodziny i społeczności lokalne [Differences in living conditions. Polish families and local societies] (pp. 148–255). Warsaw: CBOS-EUROREG-SCHOLAR.

Katona, G. (1964). The mass consumption society. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Koralewicz, J., & Zagórski, K. (2009). Living conditions and optimistic orientation of Poles. International Journal of Sociology, 39(4), 10–44. doi:10.2753/IJS0020-7659390400.

Maslow, A. H. (1962). Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand Company.

Maslow, A. H. (1964). Teoria hierarchii potrzeb. In J. Reykowski (Ed.), Problemy osobowości i motywacji w psychologii amerykańskiej. Warszawa: PWN.

Medgyesi, M. (2008). Income distribution in European countries: First reflections on the basis of EU-SILC 2005. In TARKI European Social Report (pp. 88–105). Budapest: TARKI.

Merton, R. K. (1957). Teoria socjologiczna i struktura społeczna [social theory and social structure]. Warszawa: PWN.

Petersen, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25–41. doi:10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z.

Plato, (1892). The dialogues of Plato. New York: Random House.

Schyns, P. (2002). Wealth of nations, individual income and life satisfaction in 42 countries: A multilevel approach. In B. D. Zumbo (Ed.), Advances in quality of life research 2001 (pp. 5–40). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Sirgy, M. J. (2002). The psychology of quality of life. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Tatarkiewicz, W. (1976). Analysis of happiness. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Van Praag, B. M. S., & Carbonell, A. F. I. (2008). Happiness quantified—a satisfaction calculus approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Veblen, T. (1994). The theory of the leisure class. In A. J. Mortimer (Ed.), Great books of the western world, vol. 57 (20th Century Social Science I). Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica.

Veenhoven, R. (1989a). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Company.

Veenhoven, R. (Ed.). (1989b). How harmful is happiness?. Rotterdam: Universitaire Press.

Veenhoven, R. (1997). Quality of life in individualistic society: A comparison of 43 nations in early 1990 s. In M. J. de Jong & A. C. Zijderveld (Eds.), The gift of society (pp. 149–170). Nijkerk: Enzo Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2005). Apparent quality-of-life in nations: How long and happy people live. Social Indicators Research, 71(1–3), 61–86. doi:10.1007/s11205-004-8014-2.

Wciórka, B. (2005). Zadowolenie z życia i kondycja psychiczna Polaków. [Life Satisfaction and Psychological Conditions of Poles]. In K. K. Zagórski & M. Strzeszewski (Eds.), Polska–Europa–Świat: Opinia publiczna w okresie integracji.[Poland–Europe–World: Public opinion in time of transformation]. (pp. 218–307). Warszawa: CBOS—Wyd Naukowe Scholar.

Zagórski, K. (2005). Life cycle, objective and subjective living standards and life satisfaction. W: Fellows, D. S. (red.). Excellence in international research—2005. Amsterdam: ESOMAR.

Zagórski, K. (2008). Obiektywny i subiektywny poziom bytu i zadowolenie z życia—Polska 1992–2004. Propozycja nowych indeksów. In H. Domański (Ed.), Zmiany stratyfikacji społecznej w Polsce. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo IFiS PAN.

Zagórski, K. (2009). Dochody, ubóstwo, zamożność i nierówności w przestrzeni społeczno-geograficznej”. In K. Zagórski, G. Gorzelak, & B. Jałowiecki (Eds.), Zróżnicowania warunków życia—Polskie rodziny i społeczności lokalne. Warszawa: CBOS-EUROREG-SCHOLAR.

Zagórski, K., Evans, M. D. R.,& Kelley, J. (2005). Individual’s subjective situation and nation’s level of socio-economic development. In Search for a new world order—the role of public opinion—book of papers, 28th annual conference, WAPOR, Cannes.

Zagórski, K., & Grabowska, M. (2009). Introduction—the social context of living conditions in Poland. International Journal of Sociology, 39(4), 3–9.

Zagórski, K., Kelley, J., & Evans, M. D. R. (2010). Economic development and happiness: Evidence from 32 nations. Polish Sociological Review, pp. 3–19.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper was prepared for the XVII ISA World Congress of Sociology, Gothenburg, July 2010.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zagórski, K. Income and Happiness in Time of Post-Communist Modernization. Soc Indic Res 104, 331–349 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9749-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9749-6