Abstract

The literature on bullying perpetration is underpinned by gendered undertones, commonly portraying men as bullies given men’s greater tendency to exhibit stereotypically masculine and overtly grandiose features of narcissism. Due to the lack of gender-sensitive inventories employed, the association between narcissism and bullying perpetration among women remains understudied. Using an all-women sample (N = 314), the current study explored grandiose narcissism (overtly immodest and domineering) and vulnerable narcissism (hypersensitive and neurotic), the latter being more prevalent among women, in relation to bullying peers. Correlation analyses showed that vulnerable narcissism was positively associated with verbal, physical, and indirect bullying. At the subscale level, contingent self-esteem, devaluing, and entitlement rage were positively associated with all three types of bullying. Grandiose narcissism was positively associated with physical and verbal bullying, as was grandiose fantasy at the subscale level, and exploitativeness was positively associated with all three types of bullying. When grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were simultaneously entered into a regression model, only vulnerable narcissism emerged as a positive predictor of physical and verbal bullying. At the subscale level, devaluing positively predicted verbal and indirect bullying, whereas hiding the self negatively predicted indirect bullying. Expressions of vulnerable narcissism, more so than grandiose narcissism, may be relevant for bullying perpetration among women. Implications for anti-bullying interventions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Narcissism is a personality trait, the extreme form of which is conceptualised as a personality disorder in the psychiatric nomenclature (DSM-5), and entails pronounced grandiosity, interpersonal exploitation, an exaggerated sense of superiority, need for admiration, inflated self-esteem, lack of empathy, and entitlement (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Over the past 20 years, trait narcissism has been recognised as a heterogenous construct, spanning features of grandiosity and vulnerability (Cain et al., 2008). Grandiose narcissism is the most prototypical form of narcissism, and refers to individuals who are extraverted, disagreeable, self-enhancing, attention-seeking, domineering, and overtly immodest (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Vulnerable narcissism refers to individuals who are introverted, neurotic, distrustful of others, emotionally hypersensitive, coy, and experience substantial psychological distress and fragility (Pincus et al., 2009). Although these two variations of narcissism share similar antagonistic features (i.e., self-centeredness, sense of entitlement, lack of empathy, and exploitation), they differ in emotional negativity and agency (Miller et al., 2021).

A review of the empirical literature reveals that trait narcissism is predominantly assessed with measures of grandiose narcissism (e.g., Narcissistic Personality Inventory; NPI; Yakeley, 2018), and more prevalent in men and boys compared to women and girls, with men being 75% more likely to be diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder (Grijalva et al., 2014). Gender disparities in vulnerable narcissism are less consistent, with some research reporting no differences (e.g., Grijalva et al., 2014; Weidmann et al., 2023), and other reviews reporting a higher prevalence among women (Green et al., 2022), with effect sizes ranging from small to medium (Pincus et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2010). The marked gender differences in narcissism may be linked to gender socialisation patterns, whereby boys may be socialised to exhibit grandiose features that imitate masculine features associated with physical aggression and assertiveness, and girls may be socialised to manifest vulnerable features that reflect feminine characteristics, including low self-esteem and emotional hypersensitivity (Green et al., 2020a). Further, the robust gender difference in grandiose narcissism suggests that prevailing measures of grandiose expressions (which dominate the assessment of narcissism) may not generalise to women and girls. Therefore, distinguishing between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism may be especially relevant for understanding the role of narcissism in other gendered social behaviours.

Linking Narcissism to Bullying Perpetration

Of particular interest in this study is the distinct role of these components of narcissism in bullying behaviour among women. Bullying is defined as repeated verbal (e.g., threatening to harm another person), psychological (e.g., ostracise peers to enact revenge), or physical aggression (e.g., forcefully pushing someone) with the intent to harm or distress those involved (Fanti & Kimonis, 2012). Recent scholarship recognises bullying as the strategic attempt to acquire a powerful and dominant position in the peer group (Reijntjes et al., 2016). Indeed, early research identified three specific criteria for bullying: (1) aggressive behaviour directed toward an individual or group, (2) which occurs repeatedly over a period, and (3) with an imbalance of power being evident (Olweus, 1994). The driving motivation for bullies to gain status, power, and dominance over others suggest that narcissism might be a contributing factor.

Grandiose narcissism has been consistently associated with the perpetration of bullying in friendships, motivated by elevated traits of entitlement, privileged status, power, exploitation, low empathy, and excessive need for admiration (Farrell & Vaillancourt, 2020; Fanti & Henrich, 2015; Maass et al., 2018; van Geel et al., 2017). Perhaps unsurprisingly, narcissistic individuals are unable to maintain friendships long-term due to their antagonistic behaviours. Maass et al. (2018) reviewed the literature on narcissism and friendships which revealed that narcissistic individuals tend to harbour feelings of hostility towards friends and reduce their closeness when they feel that the admiration and status which they demand has not been offered by their peers. Furthermore, narcissistic individuals aggress and bully peers who threaten their ego, to restore ‘injury’ caused to their self-esteem, and to maintain their perceived superiority (Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021).

Several studies report that more grandiose narcissistic features among men and boys predict more frequent bullying of peers compared to women and girls (e.g., Baughman et al., 2012; Fanti & Kimonis, 2012; Reijntjes et al., 2016). For instance, Baughman et al. (2012) explored grandiose narcissism as part of the ‘dark triad’ (including Machiavellianism and psychopathy) in relation to bullying perpetration in an adult sample. Compared to women, men scored significantly higher on grandiose narcissism and were significantly more likely to enact physical aggression, verbal aggression, and indirect aggression compared to women. These gender patterns have been supported in a longitudinal study which measured school bullying in adolescence (Fanti & Kimonis, 2012). Grandiose narcissism was measured at baseline using seven items from the Antisocial Process Screening Device-Youth Version (APSD), which boys scored significantly higher on compared to girls. Compared to girls, boys were also significantly more likely to perpetrate direct bullying (e.g., hitting, calling names) and indirect bullying (e.g., gossiping, spreading rumours) at age 12, age 13, and age 14.

Another longitudinal study by Reijntjes and colleagues (2016) further explored these gender differences in a sample of children. A three-wave study was conducted which followed children from late childhood into early adolescence to explore grandiose narcissism (assessed with the Childhood Narcissism Scale; CNS) and bullying (distinguished by direct and indirect forms). Across waves, boys scored significantly higher on grandiose narcissism compared to girls and both direct and indirect bullying. Overall, these findings provide support for consistent gender patterns in narcissism and bullying over time and across age groups, which has led research to conclude that elevated (grandiose) narcissism is a risk factor for bullying in boys and men, but not in girls and women (Reijntjes et al., 2016).

Research Gaps on Vulnerable Narcissism and Bullying by Women

Notwithstanding the merits of the above studies, important research gaps remain. The gender patterns reported in previous research are based on the grandiose features of narcissism, which are significantly more prevalent in men. Therefore, narcissistic features in women are arguably not accurately assessed, and their perpetration of bullying behaviours may be marginalised. Indeed, research has only begun to explore narcissism in women and their offending behaviours using gender-sensitive assessments (i.e., Green et al., 2020b). Green and colleagues’ (2020b) findings revealed that vulnerable narcissism, but not grandiose narcissism, was a significant predictor of aggressive and violent offending in women. This is noteworthy given that women’s manifestations of (vulnerable) narcissism and their aggressive behaviour are, as perceived by close others, more elusive and consequently underestimated as they deviate from stereotypically masculine behaviours associated with narcissism (Green et al., 2019). These findings conceivably reflect gendered self-regulation strategies by which women attain their self-motives of power in more discreet and subtle manners, due to fears of violating feminine gender norms.

Although research on bullying among women is relatively scant compared to bullying among men, the literature has, similarly, attempted to explain existing gender differences because of normative societal expectations of girls and boys that guide bullying behaviour. Here, boys are socialised to use direct physical and verbal aggression, whereas girls are socialised to vent their aggression indirectly (Hellström & Beckman, 2020; Smith et al., 2019). Compared to boys, girls tend to adopt more relational aggression indicative of manipulation, social ostracism of peers, and spreading vicious rumours (Hellström & Beckman, 2020). These gender patterns in aggressive expression extend to the narcissism literature, where men’s aggression is more overtly grandiose and linked to an inflated self-image (Ryan et al., 2008), and women’s aggression is more indirect and subtle in nature (Green et al., 2019) and linked to a low self-esteem (Barnett & Powell, 2016).

Overall, the literature on narcissism and bullying has been dominated by the assessment of grandiose narcissism and consistently portrayed bullying perpetration as more prevalent in men. This is particularly concerning given that recent meta-analytic findings suggest vulnerable narcissism is a greater risk factor for aggression than grandiose narcissism (Zhang & Zhu, 2021), and vulnerable narcissism was found to be the only significant predictor of aggression and violence in women (Green et al., 2020b). Most of the research into bullying has also been conducted on children and adolescence, whereas less is known about adult bullying (Baughman et al., 2012). These findings have implications for considering risk and protective factors of bullying interventions, as they apply to men and women. Bullying has severe and long-lasting consequences, associated with lowered mental well-being and increased signs of stress and psychosomatic symptoms (Einarsen & Mikkelsen, 2003; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2010). Therefore, theoretical knowledge regarding bullying perpetration by women with specific features of narcissism is a crucial precondition for developing new interventions.

Current Study

This study addresses shortcomings in previous research by examining the association between vulnerable and grandiose narcissism and bullying behaviour in adult women. Consistent with Green and colleagues’ (2020b) finding that vulnerable narcissism, but not grandiose narcissism, was a significant predictor of aggressive and violent offending in women, we predict that the same pattern will emerge in the context of bullying peers. Specifically, we hypothesise that vulnerable narcissism, but not grandiose narcissism, will predict indirect, physical, and verbal bullying (H1). We also explore the associations between individual facets of vulnerable narcissism (i.e., hiding the self, entitlement rage, devaluing, contingent self-esteem) and grandiose narcissism (i.e., self-sacrificing self-enhancement, exploitatitveness, and grandiose fantasies), and bullying perpetration to examine what is driving these effects. In line with prior work which associates narcissism with indirect and direct forms of aggression in women (Green et al., 2019; 2020b), we expect the interpersonally exploitable and antagonistic subcomponents of vulnerable narcissism (i.e., entitlement rage, devaluing, and contingent self-esteem) will positively predict indirect, physical, and verbal bullying perpetration (H2). The current study will also explore whether endorsement of these variables differ depending on participant sample as data were collected from university students and using social media platforms.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited via adverts circulated on social media (Twitter, Instagram, Facebook) (n = 169, 53.8%) and the participant pool at City University of London (n = 145, 46.2%) in the U.K for a study on ‘personality traits in friendships’. Recruitment fliers contained a link which directed participants to the online study, where they were presented with demographic questions, followed by the Pathological Narcissism Inventory, and finally the bullying questionnaire. All participants read a debrief sheet upon completion and had the option to enter a prize draw for a £50 voucher. This study was approved by City University of London Research Ethics Committee.

A power analysis was conducted using G*Power (version 3.1.9.2; Faul et al., 2007) to calculate the minimum sample size needed to achieve a desired moderate effect size (f2 = 0.15) with an alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.80 using a multiple regression with seven predictor variables (representing seven subscales from the Pathological Narcissism Inventory). A minimum of 103 participants was required to detect an effect with 80% probability. A total of 510 participants completed the study, however, data pertaining to 195 participants were removed due to incomplete responses or for not identifying as a woman.

The final sample consisted of 314 women aged 18–76 (M = 24.32, SD = 10.92), with the majority identifying as White European (n = 147, 46.8%), South or East Asian (n = 69, 22.0%), African (n = 14, 4.5%), Middle Eastern (n = 12, 3.8%), and Hispanic or Latino (n = 11, 3.5%). The remaining participants (n = 61, 19.4%) chose ‘mixed’ or ‘other’ for ethnicity.

Measures

Pathological Narcissism Inventory

The Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI; Pincus et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2010) is a 52-item self-report measure assessing both vulnerable (34 items) and grandiose (18 items) narcissism. The PNI is widely used in non-clinical samples (Edershile et al., 2018) and research exploring narcissism and aggression (for a review, see Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021). Vulnerable narcissism is operationalised with four subscales: contingent self-esteem (12 items, e.g., ‘‘My self-esteem fluctuates a lot”; α = 0.89), hiding the self (seven items, e.g., “‘I often hide my needs for fear that others will see me as needy and dependent”; α = .71), devaluing (seven items, e.g., “I sometimes feel ashamed about my expectations of others when they disappoint me”; α = .77), and entitlement rage (eight items, e.g., “I get angry when criticized”; α = .82). We created an overall index of vulnerable narcissism by computing a mean of these 34 items (α = .92) in addition to computing means for each of the subscales. Grandiose narcissism is operationalised with three subscales: exploitativeness (five items, e.g., “I find it easy to manipulate people”; α = .63), self-sacrificing self-enhancement (six items, e.g., “I try to show what a good person I am through my sacrifices”; α = .68), and grandiose fantasy (seven items, e.g., “I often fantasise about being recognised for my accomplishments”; α = .84). We created an overall index of grandiose narcissism by computing a mean of these 18 items (α = .85), in addition to computing means for each of the subscales. Responses for all items are made on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me), with higher scores indicating higher levels of narcissism on each subscale and on overall indices of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism.

Bullying Questionnaire

The Bullying Questionnaire (Baughman et al., 2012) contains 17 items assessing bullying behaviours and includes three subscales: physical direct (five items, e.g., ‘I forcefully pushed/pulled someone’; α = 0.80), verbal direct (seven items, e.g., “I threatened to harm another person”; α = 0.85), and indirect (five items, e.g., “I have spread negative rumours about someone that may or may not have been true”; α = 0.88). This questionnaire was developed specifically to assess bullying in adults. As the current study focuses on bullying perpetration in peer relationships, participants were asked to indicate whether they had bullied anyone during a friendship, or in a most recent friendship. Items were endorsed on a 6-point scale; 0 (this has never happened), 1 (this has happened once), 2 (this has happened twice in the past), 3 (this has happened 3–5 times in the past), 4 (this has happened 6–10 times in the past), and 5 (this has happened 20 times or more in the past). Mean scores were calculated with higher scores indicating more frequent bullying of peers.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Prior to data analysis, the data were checked for missing values using the missing completely at random test (MCAR; Little & Rubin, 2002). The test was non-significant (χ2 = 645.61, df = 608, p = .141), indicating the missing data were due to random causes. In terms of methods to replace missing data, it was decided that, in cases where participants failed to indicate their age (n = 2) or ethnicity (n = 1), missing values were not replaced and therefore accepted as missing data. Responses that were missing for the PNI scale (13 items) and the Bullying scale (8 items) were replaced by imputing the mode substitution method for consistency purposes. Replacing values using the mode is a standard and basic imputation method and, compared to the mean substitution method, does not reduce variance in the dataset (Baraldi & Enders, 2010). Other methods, such as regression imputation, were deemed inappropriate due to the risk of reinforced correlation estimates which may affect the generalisability of the findings (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013).

Descriptive Statistics

All variables showed acceptable levels of skew (less than 2) and kurtosis (less than 7), except for indirect bullying, which showed some positive skew (2.07, SE = 0.14). Field (2009) suggests that values of kurtosis and skewness should have no upper criterion applied in sample sizes > 200. Therefore, assumptions of normality were assumed given the sample size of the current study.

Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations between narcissism and bullying outcomes are shown in Table 1. One sample t-tests were performed on the means. The mean scores for vulnerable narcissism did not differ significantly from the scale midpoint (3.5), t(313) = 0.18, p = .430. Of the vulnerable subscales, hiding the self, devaluing, and entitlement rage differed significantly from the scale midpoint (3.5), t(313) = 9.96, p < .001, t(313) = -4.47, p < .001, and t(313) = -3.21, p < .001, respectively, whereas contingent self-esteem did not differ from the scale midpoint (3.5), t(313) = -0.80, p = .213. The mean scores for grandiose narcissism differed significantly from the scale midpoint (3.5), t(313) = 2.64, p = .004. Of the grandiose subscales, self-sacrificing self-enhancement and grandiose fantasy differed significantly from the scale midpoint (3.5); t(313) = 4.26, p < .001 and t(313) = 3.11, p < .001, respectively, whereas exploitativeness did not differ from the scale midpoint (3.5), t(313) = -1.16, p = .123. Furthermore, the means scores for physical, verbal, and indirect bullying were all significantly lower than the scale midpoint (2.5), t(313) = -22.65, p < .001, (313) = -20.32, p < .001, t(313) = -27.96, p < .001, respectively.

Consistent with previous research (Pincus et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2010), overall vulnerable narcissism scores were positively and moderately associated with overall grandiose narcissism scores. Overall vulnerable narcissism scores were positively and weakly associated with all three bullying types (physical, verbal, and indirect). At the subscale level, contingent self-esteem, devaluing, and entitlement rage were positively and significantly associated with all three types of bullying (see Table 1). Overall grandiose narcissism scores were positively and weakly correlated with physical and verbal bullying, but not indirect bullying. At the subscale level, exploitativeness was positively and weakly associated with all three types of bullying and grandiose fantasy was positively and weakly associated with physical and verbal forms of bullying (see Table 1).

Fisher’s r to z tests were computed to directly compare the strength of the associations between vulnerable and grandiose narcissism and each type of bullying. Using an online calculator (https://www.psychometrica.de/correlation.html), we entered the correlation and sample size between vulnerable narcissism and physical bullying, and grandiose narcissism and physical bullying. No significant difference was found, z = 1.16, p = .145. We entered the correlation and sample size between vulnerable narcissism and verbal bullying, and grandiose narcissism and verbal bullying. No significant difference was found, z = 1.06, p = .122. Finally, we entered the correlation and sample size between vulnerable narcissism and indirect bullying, and grandiose narcissism and indirect bullying. No significant difference was found, z = 1.02, p = .154.

Independent t-tests were conducted on demographic and key study variables to test whether participants’ scores differed depending on whether they were recruited via social media or from the university participant pool (see Table 2). Our samples differed on age; the university sample was significantly younger than the social media sample. Significant differences emerged for all three types of bullying, with the social media sample reporting more frequent bullying than the university sample. The social media sample also scored significantly higher on entitlement rage than the university sample. We therefore controlled for sample in subsequent analyses.

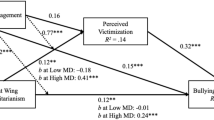

Vulnerable and Grandiose Narcissism as Predictors of Bullying

Simultaneous multiple regression models were conducted to examine vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as predictors of bullying perpetration. These regression models were performed separately for each outcome variable (physical, verbal, and indirect bullying), as shown in Tables 3 and 4, and 5, respectively. Accordingly, a Bonferroni correction was applied such that we adopted a stricter alpha level of 0.01 (0.05/3) to reduce the likelihood of familywise error.

Physical Bullying

In testing H1, a regression model testing overall vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as simultaneous predictors, of physical bullying, controlling for sample source, was statistically significant, F(3, 310) = 11.45, p < .001, R2 = 0.10 (see Table 3). Participants scoring higher on vulnerable narcissism were significantly more likely to report engaging in physical bullying. The relationship between grandiose narcissism and physical bullying was positive but non-significant. Vulnerable narcissism uniquely accounted for 2.76% of the variance in physical bullying whilst grandiose narcissism uniquely accounted for less than 1% of the variance in physical bullying.

In testing H2, a separate model that included the seven subscales of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as predictors of physical bullying, controlling for sample source, was also significant, F(8, 305) = 7.26, p < .001, R2 = 0.16. However, applying the Bonferroni-corrected alpha level, none of the seven predictors were significant.

Verbal Bullying

In testing H1, a regression model testing overall vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as simultaneous predictors of verbal bullying, controlling for sample source, was statistically significant, F(3, 310) = 21.58, p < .001, R2 = 0.17 (see Table 4). Those scoring higher on vulnerable narcissism were more likely to report engaging in verbal bullying. The relationship between grandiose narcissism and verbal bullying was positive but non-significant. Vulnerable narcissism uniquely accounted for 3.20% of the variance in verbal bullying whilst grandiose narcissism uniquely accounted for less than 1% of the variance in verbal bullying.

In testing H2, a model that included the seven subscales of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as predictors of verbal bullying, controlling for sample source, was also significant, F(8, 305) = 12.10, p < .001, R2 = 0.24. Participants scoring higher on the devaluing subscale were more likely to report engaging in verbal bullying.

Indirect Bullying

In testing H1, a regression model testing overall vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as simultaneous predictors of indirect bullying, controlling for sample source, was statistically significant, F(3, 310) = 17.55, p < .001, R2 = 0.15 (see Table 5). Participants scoring higher in vulnerable narcissism were not more likely to report engaging in indirect bullying using our stricter significance levels. The relationship between grandiose narcissism and indirect bullying was positive but non-significant. Vulnerable narcissism uniquely accounted for 1.77% of the variance in indirect bullying whilst grandiose narcissism uniquely accounted for less than 1% of the variance in indirect bullying.

In testing H2, a model that included the seven subscales of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as predictors of indirect bullying, controlling for sample source, was also significant, F(8, 305) = 11.42, p < .001, R2 = 0.23. Those scoring lower on hiding the self and higher on devaluing were more likely to report engaging in indirect bullying.

Discussion

This study sought to contribute to the scant literature on narcissism in women and their enactment of bullying toward their peers through an examination of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism in relation to verbal, indirect, and physical bullying. Correlational analyses revealed that women exhibiting higher levels of vulnerable narcissism traits were significantly more likely to report enacting physical, verbal, and indirect forms of bullying towards their peers. More specifically, greater endorsement of traits reflective of contingent self-esteem, devaluing, and entitlement rage were positively associated with all three types of bullying. The results also indicated that women scoring higher on grandiose narcissism were more likely to perpetrate verbal and physical forms of bullying towards their peers. More specifically, endorsement of exploitativeness was positively associated with all three types of bullying, whereas endorsement of grandiose fantasy was positively associated with physical and verbal forms of bullying.

Although zero-order correlations suggest that both forms of narcissism are positively associated with various bullying indices, and that the strength of correlations between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism on bullying indices were not significantly different, only vulnerable narcissism predicted unique variance in physical and verbal bullying in the regression models when both narcissistic subtypes were considered simultaneously (consistent with H1), and with devaluing specifically predicting verbal and indirect bullying (partly consistent with H2). In contrast to the literature which links indirect forms of bullying perpetration with women (e.g., Hellström & Beckman, 2020), our findings suggest that bullying among narcissistic women is not necessarily only expressed in relational and subtle ways and extends the literature on male-perpetrated bullying that is commonly expressed as direct and overt aggression in friendships (e.g., Baughman et al., 2012; Fanti & Kimonis, 2012; Reijntjes et al., 2016).

At first glance, it may be conceivable to interpret the overt forms of bullying as indicative of women exhibiting traits (e.g., overt superiority, entitlement, and assertiveness) that do not conform with their expected gender norms. It is argued here, however, that gendered self-regulatory strategies in women may precipitate vulnerable narcissistic expressions as a means to obtain their self-worth in more elusive ways, as vulnerable expressions differ from the ubiquitous and masculine-derived conceptualisation of (grandiose) narcissism typically viewed in men. In other words, although narcissistic women appear to aggress in similar ways as narcissistic men, women’s vulnerable presentation of narcissism may be a more effective disguise to express violence in both indirect and direct ways to acquire and preserve power in friendships, whilst minimising risks regarding violations of normative expressions (Green et al., 2019; 2020b, 2022). These gendered self-regulatory strategies may reflect developmental and socialised differences whereby narcissistic women use more tactful and subtle means in their strive for power and status (Green et al., 2019; 2020b).

Interestingly, devaluing emerged as the primary subscale predictor of verbal and indirect bullying. This factor captures a shameful dependency on others to provide admiration needs and enragement when such expectations are not met (Pincus et al., 2009). In relation to bullying, narcissistic women may devalue their peers by engaging in emotionally hurtful behaviours by, for instance, making threats to end the friendship, spreading pernicious rumours, and socially alienating their peers from friendship groups in responses to ‘narcissistic injury’ (Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021). The current findings also showed that women who scored higher on hiding the self were less likely to perpetrate indirect bullying towards their peers. This subcomponent captures an individual with an anxious and shame-ridden self-preoccupation, conceivably resulting in social avoidance to cope with fears of failure and rejection (Pincus et al., 2009). Taken together, the present study reveals that vulnerable narcissism, but not grandiose narcissism, may be a more relevant and understudied risk factor for bullying among women.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. Many participants (n = 195) were removed due to incomplete responses or for not identifying as a woman (n = 8). However, given the sensitivity of the topic area, the completion rate in our study is not surprising or concerning. In addition, a recent meta-analysis shows that the average online survey response is 44.1% (Wu et al., 2022). The PNI subscales used in the current study generally demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach, 1951), except for exploitativeness and self-sacrificing self-enhancement, both of which showed lower levels of reliability (< 0.7). Furthermore, women may have felt less inclined to reveal their involvement in bullying perpetration, particularly as overt types of bullying (i.e., physical aggression) violate feminine gender stereotypical norms. Future research should consider including a measure of social desirability to control for biased responding. The Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (Paulhus, 1984), for example, assesses both impression management and self-deceptive enhancement, thus allowing researchers to control for self-reporting that both attempts to present oneself in a favourable light and provide honest but overly positive responses.

It is also important to consider whether the assessment of bullying used in the current study is gendered and the extent which it may have influenced the results. It is argued here that the assessment used covers a wide variety of bullying behaviours (indirect, verbal, and direct forms), which are not only comparable with other bullying measures in the literature (Baughman et al., 2012), but also captures aggressive behaviours typically displayed by both women (indirect and covert) and men (direct and overt). As such, it is recommended that future research similarly include the full dimension of bullying perpetration to better understand the range of aggressive behaviours which women might engage in. The current study also failed to gather information about the gender of the target, which may have influenced how participants responded to bullying perpetration. Future research should investigate whether indirect or direct forms of bullying are more likely endorsed depending on the gender of the target. In addition to this, given that direct gender comparisons were not possible in this study, future research should also include both men and women to further enhance gendered patterns and risk markers for bullying in narcissistic perpetrators.

Another limitation pertains to the cross-sectional nature of the current findings, which are also context specific (recollections of current or past friendships) and may result in memory distortions of such recollections. Another line of enquiry could therefore be to replicate our results by exploring gender differences in bullying behaviours longitudinally and across different contexts (e.g., work, school). Such foci will further inform and help evaluate the effectiveness and implications of different anti-bullying programs (Smith et al., 2019). This is particularly noteworthy as research reports that specific types of bullying in girls (i.e., relational bullying), has been taken less seriously by school staff, in comparison to overt forms of bullying which were more likely intervened through various strategies such as peer resolution, class discussions, reporting to higher authority, and informing the parents (Bauman & Del Rio, 2006).

Practical Implications

The current findings have implications for the theoretical literature on grandiose narcissism, where research on bullying by women has been overshadowed by research on bullying by men (e.g., Baughman et al., 2012; Fanti & Kimonis, 2012; Reijntjes et al., 2016). Employing more gender-sensitive assessments of narcissism within the context of bullying would help to identify the specific narcissistic markers that may underlie patterns of bullying among women. As evidence accumulates for the unique and significant role of vulnerable narcissism in women’s bullying behaviour, interventions may be tailored to address specific facets of narcissism, such as devaluing. For instance, efforts could be placed on encouraging positive self-perceptions that do not rely on external validation, through focusing on existing merits that enhances positive self-evaluation and reduces internalising symptoms which are specific to narcissistic vulnerability (e.g., envy, humiliation, shame, depression).

In addition, empathy training could be implemented to foster emotion management, anger regulation, conformity to social norms and increased quality of friendships, which may reduce the possibility of engagement in relational bullying. Here, clinicians are encouraged to target the psychological processes inherent in narcissistic women that inhibit their ability to emphasise with others – specifically their tendency to envy others, and therefore view themselves as a victim to justify their enactment of behaving aggressively towards others (Day et al., 2020). By addressing specific elements of narcissism in women to encourage positive self-perceptions and empathy training, interventions could potentially enable narcissistic women to acquire their status and self-regard through alternative means that are not based on aggressive behaviours.

Conclusion

The current study provides novel and finer-grained knowledge regarding the manifestations of narcissism in women and their association with the perpetration of different forms of bullying in friendships. Although both forms of narcissism were related to various bullying indices at the bivariate level, only vulnerable narcissism predicted unique variance in physical and verbal bullying in the regression models when considered simultaneously with grandiose narcissism. At the subscale level, only devaluing emerged as a significant positive predictor of verbal and indirect bullying. These findings stress the importance of assessing narcissistic features in women beyond grandiose features commonly ascribed to stereotypical masculine gender norms and embodied by men. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that vulnerable narcissistic traits (and specifically devaluing) in women should not be marginalised in research or practice, as they are associated with all forms of bullying. These findings can inform targeted anti-bullying interventions that are tailored to meet the needs of vulnerable narcissistic women.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association.

Baraldi, A. N., & Enders, C. K. (2010). An introduction to modern missing data analyses. Journal of School Psychology, 48(1), 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2009.10.001.

Barnett, M. D., & Powell, H. A. (2016). Self-esteem mediates narcissism and aggression among women, but not men: A comparison of two theoretical models of narcissism among college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.042

Baughman, H. M., Dearing, S., Giammarco, E., & Vernon, P. A. (2012). Relationships between bullying behaviours and the Dark Triad: A study with adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(5), 571–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.020.

Bauman, S., & Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice teachers’ responses to bullying scenarios: Comparing physical, verbal, and relational bullying. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.219.

Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555.

Day, N. J. S., Townsend, M. L., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2020). Living with pathological narcissism: A qualitative study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-020-00132-8.

Edershile, E. A., Simms, L. J., & Wright, A. G. C. (2018). A multivariate analysis of the pathological narcissism inventory’s nomological network. Assessment, 26(4), 619–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118766412.

Einarsen, S., & Mikkelsen, E. G. (2003). Individual effects of exposure to bullying at work. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and emotional abuse in the workplace: International perspectives in research and practice (pp. 127–144). Taylor & Francis.

Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, C. C. (2015). Effects of self-esteem and narcissism on bullying and victimization during early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431613519498.

Fanti, K. A., & Kimonis, E. R. (2012). Bullying and victimization: The role of conduct problems and psychopathic traits. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(4), 617–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00809.x.

Farrell, A. H., & Vaillancourt, T. (2020). Bullying perpetration and narcissistic personality traits across adolescence: Joint trajectories and childhood risk factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, Article 483229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.483229.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage.

Green, A., Charles, K., & MacLean, R. (2019). Perceptions of female narcissism in intimate partner violence: A thematic analysis. Qualitative Methods in Psychology Bulletin, 28, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsqmip.2019.1.28.13.

Green, A., MacLean, R., & Charles, K. (2020a). Recollections of parenting styles in the development of narcissism: The role of gender. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, Article 110246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110246.

Green, A., MacLean, R., & Charles, K. (2020b). Unmasking gender differences in narcissism within intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, Article 110247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110247.

Green, A., MacLean, R., & Charles, K. (2022). Female narcissism: Assessment, aetiology, and behavioural manifestations. Psychological Reports, 125(6), 2833–2864. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211027322.

Grijalva, E., Newman, D. A., Tay, L., Donellan, M. B., Harms, P. D., Robins, R. W., & Yan, T. (2014). Gender differences in narcissism: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 141(2), 261–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038231.

Hellström, L., & Beckman, L. (2020). Adolescents’ perception of gender differences in bullying. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12523.

Kjærvik, S. L., & Bushman, B. J. (2021). The link between narcissism and aggression: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(5), 477–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000323.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Maass, U., Wehner, C., & Ziegler, M. (2018). Narcissism and friendships. In A. D. Hermann, A. Brunell, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), The handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 345–354). Springer.

Miller, J. D., Back, M. D., Lynam, D. R., & Wright, A. G. C. (2021). Narcissism today: What we know and what we need to learn. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(6), 519– 525. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211044109.

Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at School. In: Huesmann, L.R. (eds) Aggressive behavior. The plenum series in social/clinical psychology. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9116-7_5.

Paulhus, D. L. (1984). Two-component models of socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(3), 598–609. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.3.598.

Pincus, A. L., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G. C., Levy, K. N., & Ansell, E. B. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the pathological narcissism inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016530.

Reijntjes, A., Vermande, M., Thomaes, S., Goossens, F., Olthof, T., Aleva, L., & Van der Meulen, M. (2016). Narcissism, bullying, and social dominance in youth: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9974-1.

Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., Moreno‐Jiménez, B., Vergel, S., A. I., & Garrosa Hernández, E. (2010). Post‐traumatic symptoms among victims of workplace bullying: Exploring gender differences and shattered assumptions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(10), 2616–2635. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00673.x.

Ryan, K. M., Weikel, K., & Sprechini, G. (2008). Gender differences in narcissism and courtship violence in dating couples. Sex Roles, 58(11–12), 802–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9403-9.

Smith, P. K., López-Castro, L., Robinson, S., & Görzig, A. (2019). Consistency of gender differences in bullying in cross-cultural surveys. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.04.006.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson Publishing.

van Geel, M., Toprak, F., Goemans, A., Zwaanswijk, W., & Vedder, P. (2017). Are youth psychopathic traits related to bullying? Meta-analyses on callous-unemotional traits, narcissism, and impulsivity. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 48(5), 768–777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0701-0.

Weidmann, R., Chopik, W. J., Ackerman, R. A., Allroggen, M., Bianchi, E. C., Brecheen, C., Campbell, W.K., Gerlach, T.M., Geukes, K., Grijalva, E., Grossmann, I., Hopwood, C.J., Hutteman, R., Konrath, S., Küfner, A.C.P., Leckelt, M., Miller, J.D., Penke, L., Pincus, A.L., Renner, K.H., Richter, D., Roberts, B.W., Sibley, C.G., Simms, L.J., Wetzel, E., Wright, A.G.C., & Back, M.D. (2023). Age and gender differences in narcissism: A comprehensive study across eight measures and over 250,000 participants. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(6), 1277–1298. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000463.

Wright, A. G. C., Lukowitsky, M., Pincus, A., & Conroy, D. (2010). The higher order factor structure and gender invariance of the pathological narcissism inventory. Assessment, 17(4), 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191110373227.

Wu, M. J., Zhao, K., & Fils-Aime, F. (2022). Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 7, 1–11.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100206.

Yakeley, J. (2018). Current understanding of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Bjpsych Advances, 24(5), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2018.20.

Zhang, L., & Zhu, H. (2021). Relationship between narcissism and aggression: A meta-analysis. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 53(11), 1228–1243. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2021.01228.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Green, A., Hart, C.M. Mean Girls in Disguise? Associations Between Vulnerable Narcissism and Perpetration of Bullying Among Women. Sex Roles 90, 848–858 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-024-01477-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-024-01477-y