Abstract

To elucidate how ingroup identification is implicated in attitudes towards gender equality, it is important to consider that (1) people simultaneously identify with more (a nation) vs. less abstract groups (gender), and (2) gender collective narcissism is the specific aspect of ingroup identification likely to inspire opposite attitudes towards gender equality among men (negative) and women (positive), but (3) national narcissism is likely to align with men’s interests and inspire negative attitudes towards gender equality among men and women. In Study 1, we demonstrate that gender collective narcissism is the same variable among men and women. In Study 2, we show that among women (but not among men) in Poland, gender collective narcissism predicts intentions to engage in normative and non-normative collective action for gender equality. In Study 3, we show that gender collective narcissists among women endorse an egalitarian outlook, whereas gender collective narcissists among men reject it. In contrast, national narcissism predicts refusal to engage in collective action for gender equality and endorsement of an anti-egalitarian outlook among women and among men. Thus, national narcissism and gender collective narcissism among men impair pursuit of gender equality. Gender collective narcissism among women facilitates engagement in collective action for gender equality. Low gender collective narcissism among men and low national narcissism may also facilitate support for gender equality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gender equality presents a different problem for men and women. For women, it is a struggle to advance the gender ingroup, often in opposition to the gender outgroup. For men, it is a struggle to give up the ingroup’s privilege, sometimes in opposition to the ingroup members, who see gender equality as a threat to their gender ingroup’s interests and image (Hässler et al., 2021; Osborne et al., 2019). Extending the findings linking women’s divergent attitudes towards gender equality to differences in the ways they define their gender identity (Mikołajczak et al., 2022), we posit that (1) the evaluative aspects of ingroup identification also matter and (2) the fact that men and women simultaneously identify with more (a nation) vs. less (gender) abstract social groups should also be taken into account. We argue that national narcissism and gender collective narcissism need to be considered to better understand how ingroup identification is implicated in attitudes towards gender equality.

Collective narcissism, a specific evaluative aspect of ingroup identification, refers to a belief that the ingroup’s exaggerated greatness is not sufficiently recognized by others (Golec de Zavala, 2011, 2023). Collective narcissism is robustly associated with an inflated preoccupation with the ingroup image, exaggeration of intergroup threat, zero-sum perceptions of intergroup situations, and intergroup antagonism (for review of findings, Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020; Golec de Zavala et al., 2019). Gender collective narcissism is likely to motivate men and women to pursue gender ingroup goals in adversarial ways, producing opposing attitudes and behavioral intentions regarding gender equality. However, national narcissism is likely to impair the pursuit of gender equality as it aligns with group interest of men rather than women. Extending past work, in three pre-registered studies, the current research examines the pattern of associations between national narcissism and gender collective narcissism among women and men and their attitudes and behavioral intentions related to gender equality.

Concept of Collective Narcissism

The concept of collective narcissism integrates concepts such as nationalism (i.e., national superiority and dominance; Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989), ingroup glorification (i.e., assumed superiority of the nation and respect for its symbols; Roccas et al., 2006), and (the lack of) subgroup respect (i.e., feeling that the subgroup is recognized and valued by members of a common group, Huo & Molina, 2006) under a common theoretical framework.

Collective narcissism is an evaluative belief that people can hold with reference to any group they belong to with similar intra- and intergroup consequences. The same collective narcissistic dynamic may drive wars waged by one nation on another (Federico et al., 2022; Golec de Zavala et al., 2009), men’s violence against women (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021), or violence unleashed by one extremist subgroup on the whole nation (Jasko et al., 2020; Yustisia et al., 2020).

Collective narcissism can be endorsed with reference to several ingroups at the same time. In fact, individual levels of collective narcissism are consistent across different social identities (Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2023; Mole et al., 2022). Importantly, narcissistic claims to the ingroup’s recognition are not solely based on the ingroup’s power or dominance. Any excuse can be used to claim the ingroup’s superiority and special deservingness. However, while national narcissism and collective narcissism of advantaged social groups (e.g., national, Catholic, male) have been intensely studied, less is known about collective narcissism in disadvantaged groups.

In the current research, we focus specifically on national narcissism and gender collective narcissism in the context of support for gender equality, and we compare the associations of national narcissism and gender collective narcissism with attitudes towards gender equality among men (the advantaged group) and women (the disadvantaged group). National narcissism is a belief that the nation’s unique greatness is not sufficiently recognized by others. Gender collective narcissism is a belief that the gender ingroup’s superiority is not sufficiently recognized by others. We expect that national narcissism and gender collective narcissism to elicit opposing attitudes towards gender equality among women, but the same attitudes towards gender equality among men. This is because national narcissism is likely to align with negative attitudes towards gender equality because it reflects men’s interests projected on the national ingroup (Brewer et al., 2013; Devos et al., 2010; van Berkel et al., 2017).

We derive our argument from social identity theory, which posits that inequalities exist because of a universal need for positive social identity (i.e., positive evaluation of the ingroup), which motivates members of advantaged groups (e.g., men) to justify unequal social systems that benefit them. At the same time, inequalities can be challenged because the same need motivates members of disadvantaged groups (e.g., women) to protest unequal social systems that harm them. Social identity theory suggests that the more people identify with their groups (i.e., the more their membership in those groups is psychologically consequential; Ellemers et al., 2002), the more the disadvantaged and advantaged groups should differ with respect to their attitudes towards equality (Tajfel & Turner, 1979).

However, the existing evidence is not conclusive and we still need to better understand: (1) why members of disadvantaged groups, even when they identify with their ingroup, sometimes endorse unequal social systems that harm it (Brandt, 2013; Caricati, 2018; Jost, 2019; Owuamalam et al., 2018, 2019); (2) why identification with the disadvantaged group is not always sufficient to mobilize collective action towards greater equality (Agostini & van Zomeren, 2021; van Zomeren et al., 2018); and (3) why some members of advantaged groups, even when they identify with their ingroup, refuse to support unequal social systems that benefit them (Radke et al., 2020). We examine national narcissism and gender collective narcissism as potential answers to these questions.

Gender Collective Narcissism and Gender Equality

We argue that gender collective narcissism should be associated with opposing attitudes and behavioural intentions regarding gender equality for women (who are likely to support gender equality) and men (who are likely to oppose gender equality). Three lines of research support this prediction.

First, extensive evidence has linked collective narcissism to an adversarial approach in intergroup relations and escalation of intergroup conflicts (Golec de Zavala, 2023). Collective narcissism is likely to inspire the perception of gender relations as a conflict, in which men and women have opposing goals. Second, collective narcissism in advantaged groups is associated with denial of group-based inequality and protection of the ingroup’s privilege. For example, white collective narcissism is positively associated with denial of the existence of anti-Black racism in the UK (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009), and with opposition to the Black Lives Matter Movement but support for white supremacist movements in the U.S. (Marinthe et al., 2022). Higher collective narcissism is also associated with less support for collective action to advance the rights of the LGBTQIA + community among heterosexual participants (Górska et al., 2020, 2023). Most pertinent to the current research, higher gender collective narcissism among men has been associated with stronger endorsement of sexist beliefs that legitimize gender inequality (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021) and less support for collective action for gender equality (Górska et al., 2023).

Third, collective narcissism in disadvantaged groups is associated with stronger attitudes toward challenging inequality. For example, Black collective narcissism is positively associated with challenging of anti-Black racism in the UK (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009) and support for the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S. (Marinthe et al., 2022). Among the LGBTQIA + community, higher collective narcissism predicts more support for gay rights and equal status (Bagci et al., 2023; Górska et al., 2020, 2023). Moreover, higher collective narcissism in disadvantaged groups, including women, is associated with a greater sense of ingroup efficacy in opposing inequality (Bagci et al., 2022). Higher gender collective narcissism among women is also associated with more distress and anger at women’s exclusion by men (Golec de Zavala, 2022). According to the social identity model of collective action (SIMCA; van Zomeren et al., 2018), anger at the ingroup’s disadvantaged status, resentment toward the discriminating outgroup, and a sense of collective efficacy are prerequisites to collective action among disadvantaged groups and have been shown to explain support for gender-based collective action among women (Iyer & Ryan, 2009; Stewart, 2017). Thus, gender collective narcissism may be a positive factor in pursuit of gender equality among women.

In sum, we predict that among men, as an advantaged gender group, gender collective narcissism will be negatively associated with an egalitarian worldview and intentions to engage in collective action for gender equality, and positively associated with conservative political beliefs that legitimize gender inequality and protect men’s privileged position as a valued ‘tradition.’ In contrast, among women, as a disadvantaged gender group, gender collective narcissism will be positively associated with an egalitarian worldview and intentions to engage in collective action for gender equality, and negatively associated with political conservatism and beliefs legitimizing gender inequality. We also expect that at low levels of gender collective narcissism, men should be more likely to support gender equality, whereas women should be less likely to support it.

Importantly, the findings reviewed above are specific to collective narcissism in comparison to another aspect of positive ingroup evaluation: non-narcissistic ingroup satisfaction, or pride in and positive evaluation of the ingroup. For example, unlike gender collective narcissism, gender ingroup satisfaction among men was not an obstacle to solidarity with women who were protesting against gender inequality in Poland (Górska et al., 2020). Gender ingroup satisfaction among men in Poland has also demonstrated a significantly weaker association with sexism than gender collective narcissism (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021). Further, among women, unlike gender collective narcissism, gender ingroup satisfaction does not predict distress and anger at the exclusion of other women (Golec de Zavala, 2022). Thus, our expectations regarding predictions of gender collective narcissism do not extend to non-narcissistic gender ingroup satisfaction. Similarly, our predictions regarding national narcissism discussed below do not extend to national ingroup satisfaction.

National Narcissism and Gender Equality

National narcissism is likely to be an obstacle in pursuit of gender equality among men and women because it is associated with the endorsement of national norms and values (Golec de Zavala et al., 2019; Mole et al., 2022). Those values reflect the interests of advantaged groups within the nation (Brewer et al., 2013; Devos et al., 2010; Sidanius et al., 1997), and in patriarchal societies, the national norms reflect the interests and values of men (Molina et al., 2014; van Berkel et al., 2017). Indeed, findings have linked stronger national identification to greater legitimization of existing inequalities among members of advantaged and disadvantaged groups (Caricati et al., 2021; Jaśko & Kossowska, 2013; Mähönen & Jasinskaja-Lahti, 2015), as well as more system-justifying political conservatism (Jost, 2019; van der Toorn et al., 2014) and gender inequality-justifying sexism (Glick & Fiske, 2001). In addition, national and gender identification have shown to be more strongly associated among men than women (van Berkel et al., 2017).

However, these findings are at odds with results indicating that a sense of shared national identity is associated with acceptance of diversity, inclusivity, support for disadvantaged groups, and a preference for egalitarian social systems (Brewer et al., 2013; Doucerain et al., 2018; Dovidio et al., 2016; Osborne et al., 2019; Sidanius et al., 1997). This inconsistency may be related to the fact that national identification is a broad concept. Its association with attitudes towards gender equality may be different depending on which aspect of national identification is taken into account. We argue that national narcissism is the specific variable linked to endorsement of the interests of advantaged groups and projection of the advantaged groups’ interests onto the whole nation. Thus, national narcissism specifically should predict less support for gender equality among men and women. Previous studies might have produced inconsistent results because they used national identification measures that varied with respect to the extent to which they tapped national narcissism.

In support of this argument, past studies have shown that national narcissism is robustly associated with prejudice justifying group-based inequalities within the nation, including racism (Golec de Zavala et al., 2020), sexism (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021), anti-gay attitudes (Mole et al., 2022), and prejudice towards immigrants and refugees (Golec de Zavala et al., 2017; Hase et al., 2021). Moreover, studies have demonstrated a strong overlap between national narcissism and Catholic (i.e., the dominant religion in Poland) collective narcissism in Poland. Polish and Catholic collective narcissism (but not ingroup satisfaction) predict more sexism (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021) and prejudice towards sexual minorities via the belief that members of the LGBTQIA + community do not represent the nation but threaten its moral integrity (Mole et al., 2022). National narcissism is also related to support for ultraconservative populism that advocates enhancement of privileges of advantaged groups as rooted in ‘traditional national values’ (Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2021). Sociological analyses also indicate that the claim of women’s worse fit to national prototypicality is used to legitimize their increasingly disadvantaged status in Poland (Graff & Korolczuk, 2022). In contrast, national ingroup satisfaction is associated with intergroup tolerance and not associated with prejudice (Golec de Zavala, 2023). Those findings suggest that (1) national narcissism specifically should predict legitimization of gender inequality and rejection of collective action for gender equality and (2) the association between national narcissism and gender collective narcissism should be stronger among men than among women.

Overview of Research

Across three studies, we examine national narcissism and gender collective narcissism as potential explanations for gender differences in the support of gender equality among women and men in Poland, a country ranked 75th in gender equality among 157 countries World Population Review (2022) and where women’s reproductive rights have recently been severely limited. First, in Study 1, we establish that gender collective narcissism is the same variable among men and women. We argue that men’s gender collective narcissism reflects claims of an exaggerated sense of the ingroup’s greatness whereas women’s gender collective narcissism reflects claims of their actual less recognized status. However, it is important to note that crucial to collective narcissism is the conviction that the ingroup should be recognized as better than others, not as equal.

To establish the conceptual equivalence of gender collective narcissism among men and women, we first determine measurement invariance of gender collective narcissism among men and women. Next, we validate the concept showing that gender collective narcissism makes the same predictions among men and women. Namely, we predict that gender collective narcissism will be positively associated with gender ingroup satisfaction, zero-sum beliefs about gender relations and gender intergroup antagonism among men and women. Those predictions are derived from collective narcissism theory and have been supported by multiple findings in contexts of other group memberships (for a review see, Golec de Zavala, 2023).

In Study 2 and 3, we test several pre-registered hypotheses regarding the role of national narcissism and gender collective narcissism in pursuit of gender equality. We argue that collective narcissists in advantaged groups want to advance inequalities, whereas collective narcissists in disadvantaged groups would support equality even if what they really want is to flip rather than attenuate social hierarchies. Thus, we propose that men and women will be more likely to endorse opposing attitudes towards gender equality at high levels of gender collective narcissism. Specifically, we predict that men will be more likely to oppose gender equality at high levels of gender collective narcissism, and more likely to support gender equality at low levels of gender collective narcissism. Women will be more likely to support gender equality at high levels of gender narcissism, and less likely to support gender equality at low levels of gender collective narcissism (Hypothesis 1). It is plausible that inconsistent findings regarding the association between ingroup identification and support for unequal social systems among advantaged group members (pointing to either positive or negative relationships; Radke et al., 2020) might have been produced by studies using ingroup identification measures that tap some degree of collective narcissism.

We also propose that women and men will report similar attitudes toward gender equality at high levels of national narcissism, showing different patterns from what is observed at high levels of gender collective narcissism among women, and thus illuminating when members of a disadvantaged group may endorse beliefs that harm their ingroup. Specifically, we predict that women and men will be less likely to support gender equality at high levels of national narcissism, but more likely to support gender equality at low levels of national narcissism (Hypothesis 2). Further, we predict that the association between gender collective narcissism and national narcissism will be weaker among women than among men (Hypothesis 3).

In Study 2, we measure behavioral intentions to engage in normative and non-normative collective action for gender equality as outcome variables. Assessing behavioral intentions is important as they are better predictors of actual behavior than beliefs and attitudes. Collective action may lead to sustainable social movement for gender equality (Selvanathan & Jetten, 2020). Thus, it is important to examine whether collective narcissism predicts intentions to engage in normative and non-normative collective action. The role of normative and non-normative collective action is different in the broader social movement. Normative collective action is more likely to elicit social support for the movement’s goals, whereas non-normative collective action may elicit hostile backlash and reduce social support for the cause of the movement (Teixeira et al., 2020). However, non-normative, moderately disruptive collective action, when combined with transparent constructive intention, works to elicit concessions from advantaged groups in pursuit of equality (Shuman et al., 2021). In Study 3, we measure endorsement of egalitarian vs. conservative ideology as outcome variables. While behavioral intentions are more closely linked to actual engagement in collective action, ideological orientations help to coordinate broader social movements and suggest potential for later involvement in collective action (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2009).

We followed journal article reporting standards recommended by Kazak (2018). All studies were approved by the university’s ethics committee. Pre-registrations are available here: https://aspredicted.org/NHZ_YWH Data generated during this project and codes for analyses are available here: https://osf.io/rvhyb/?view_only=b04cb88d06604d77af98a60d565287c7

Study 1

In Study 1, we test whether gender collective narcissism is the same variable among women and men. We first test whether gender collective narcissism can be differentiated from national narcissism and whether both can be differentiated from national and gender ingroup satisfaction. Next, we test measurement equivalence of the scale assessing gender collective narcissism (and, for comparison, gender ingroup satisfaction) across gender groups. Finally, we demonstrate that, as can be predicted from collective narcissism theory (Golec de Zavala, 2011, 2023), gender collective narcissism among men and women is similarly associated with gender ingroup satisfaction, zero-sum beliefs and gender intergroup antagonism.

Participants and Procedure

Participants were a nationally representative sample of 1088 Polish adults, comprised of 572 women and 516 men with ages ranging from 18 to 85 (M = 44.66, SD = 15.87). The random-quota sample was collected by the Ariadna Research Panel (http://www.panelariadna.com). The sample is nationally representative in terms of age, gender, and place of residence. The sample contained no missing data. Participants with missing responses were automatically removed from the data poll and replaced with new participants until representative sample was reached. Demographic questions were presented first, then the study measures were completed in random order for each participant with the order of items within measures also randomised for each participant.

Measures

Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which they agree with each item using a scale ranging from 1 (“definitely not”) to 7 (“definitely yes”). Higher scores on all scales indicate a higher degree of the variable.

National Narcissism

National narcissism was assessed with a 5-item scale used with reference to the national ingroup (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; e.g. “The true importance of Poland is rarely sufficiently recognized by others”).

Gender Collective Narcissism

Gender collective narcissism was assessed in each gender group with a 5-item scale with reference to a respective gender ingroup (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; e.g. “The true importance of women/men is rarely sufficiently recognized by others”).

National Ingroup Satisfaction

National ingroup satisfaction was assessed with the four items from the Ingroup Satisfaction subscale of the Ingroup Identification Scale with reference to the national ingroup and used previously with Polish samples (Leach et al., 2008 used in previous studies in Poland; Golec de Zavala et al., 2020, e.g. “It is good to be Polish”).

Gender Ingroup Satisfaction

Gender ingroup satisfaction was assessed with the four items from the Ingroup Satisfaction subscale of the Ingroup Identification Scale with reference to the gender ingroup and used previously with Polish samples (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021; Leach et al., 2008, e.g., “It is good to be a woman/man”).

Zero-Sum Beliefs

Zero-sum beliefs about gender relations were measured with the four items adapted from Wilkins et al. (2015): “Men/women succeed at the expense of women/men”; “Men/women get to power at the expense of women/men”; “The more the importance of men/women increases, the more the importance of women/men decreases” and “Men and women have mutually exclusive interests.” The scale was translated to Polish and back-translated by independent bilingual speakers.

Intergroup Antagonism

Intergroup antagonism between men and women was measured with three items pertaining to preference for disruptive and violent actions to push the gender ingroup’s goals forward. The items were adapted from van Prooijen and Kuijper (2020): “I am prepared to use violence to help women/men achieve their group goals”; “I am prepared to disturb the social order so the important ideals of women/men are met.” and “I am prepared to destroy public and private property if this helps women/men to achieve their goals.” The scale was translated to Polish and back-translated by independent bilingual speakers.

Results and Discussion

Factorial Structure and Measurement Invariance

First, we established that the four factor model that differentiates national narcissism and gender collective narcissism and national ingroup satisfaction and gender ingroup satisfaction (Model 1) fits the data better than: (1) a two factor model representing only collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction (gender and national combined, Model 2), (2) a two factor model representing national collective narcissism and national ingroup satisfaction combined vs. gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction combined (national vs. gender positive evaluation of the ingroup, Model 3), and (3) a one factor model representing all variables combined (Model 4). Table 1 presents the results for the four models, confirming support for the four-factor model as the best fit to the data.

Next, we tested the measurement invariance of gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction measures Measurement invariance demonstrates equivalence of latent constructs across different groups or measurement occasions (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). Invariance is required to make interpretable comparison of means and associations between constructs in different groups and evaluated in a stepwise fashion. For metric (or weak) invariance, the equivalence of the factor loadings of each item with the latent construct is tested. For scalar (or strong) invariance, the equivalence of factor loadings and intercepts for each item with the latent construct is tested. Finally, for strict invariance, the equivalence of loadings, intercepts, and residuals of each item with the latent construct is tested. Scalar invariance is required to compare means across groups, whereas metric is sufficient to compare the associations between constructs (Hirschfeld & Von Brachel, 2019).

We adopted the procedure of invariance testing suggested by Beaujean (2014; see also Hirschfeld & Von Brachel, 2019). All tests were conducted using robust maximum likelihood estimation using robust Huber-White standard errors. We used the criteria of ∆CFI < .01 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002) to judge whether the four predictors were invariant between the configural and metric models as metric invariance is sufficient to interpret the differences in associations between collective narcissism and the outcomes between the gender groups. Multiple group (with group-wise estimates among men and women) confirmatory factor analysis was carried out on the four-factor model to check whether the measures of collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction with respect to the nation and gender were invariant across gender groups. Invariance was found at the metric level (see Table 2), which allows for comparing the findings for these measures between men and women. We also tested measurement invariance per the predictor measure with the same results pointing to their metric invariance (See Table S1 in the online supplement).

Validation Analyses

Zero order correlations in Table 3 showed, as expected, that among men and women, gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction were positively associated. Gender collective narcissism was also positively associated with zero-sum beliefs and intergroup antagonism among men and women. Those results are in line with previous findings pointing to the robust positive association between collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction across group memberships as well as a robust association between collective narcissism (in any group) and zero-sum beliefs and intergroup antagonism (for a review, Golec de Zavala, 2023; Golec de Zavala et al., 2019).

Moreover, as expected, when the common overlap of gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction was accounted for in the multiple regression analysis, gender collective narcissism positively predicted the zero-sum beliefs and intergroup antagonism (see Table 4). In contrast, gender ingroup satisfaction (controlling for gender collective narcissism) was negatively associated with the zero-sum beliefs and intergroup antagonism. These findings are consistent with previous studies that point to opposite net associations of collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction with intergroup antagonism (for a review, Golec de Zavala, 2023).

Finally, the predictions for gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction were the same among men and women. Gender did not moderate the negative associations between gender ingroup satisfaction and zero-sum beliefs or intergroup antagonism (p = .67 and .49, respectively). Gender did not moderate the association between gender collective narcissism and the zero-sum conflict beliefs (p = .48), but it moderated the link between gender collective narcissism and intergroup antagonism, b(SE) = -0.28(.07), p < .001, 95% CI [-0.42, -0.15]. The link was positive among men and women, but it was stronger among men b(SE) = 0.72(.04), p < .001, 95%CI [0.63,0.80], than among women, b(SE) = 0.42(.05), p < .001, 95%CI [0.32,0.51].

The results of Study 1 indicated measurement equivalence across the gender groups for the measures of gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction among men and women. The findings also indicated that among men and women, national narcissism and gender collective narcissism and national ingroup satisfaction and gender ingroup satisfaction can be reliably assessed as distinct phenomena. The validation analyses also indicated that gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction are inversely related to zero-sum beliefs and intergroup antagonism. Having established that measurement of gender collective narcissism taps the same constructs among men and women, we compared its predictions for attitudes towards gender equality among men and women.

Study 2

In Study 2, we tested the three critical hypotheses using three distinct indicators of support for collective action for gender equality. We assessed support for specific collective action in Poland: the All-Poland Women’s Strike. The All-Poland Women’s Strike is a social movement for gender equality and women’s rights established in Poland in September 2016 in response to the government’s tightening of the already strict anti-abortion law in Poland. The All-Poland Women’s Strike has co-ordinated multiple nationwide protests against the violation of women’s rights. Protests intensified in October 2020 when the controversial Constitutional Tribunal introduced a near-total abortion ban that met with violent responses from the state and human rights violation of the protesters (Human Rights Watch, 2021).

We expected that gender collective narcissism among women would predict more support for the All-Poland Women’s Strike actions, whereas among men it would predict less support for the All-Poland Women’s Strike actions. We expected national narcissism to be negatively related to support for the All-Poland Women’s strike among men and women. We also assessed behavioral intentions to engage in collective action for gender equality, differentiating between normative collective action (political activism) and non-normative collective action (political radicalism). Political activism comprises legal, normative, and non-violent actions to support the ingroup’s goals such as belonging to political organizations or donating money or joining legal public protests. Political radicalism comprises non-normative, illegal, and sometimes also violent political action, such as belonging to an organization that breaks the law to advance the ingroup’s goals, participation in violent protests, and violent street actions (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2009).

We expected that gender collective narcissism among women would predict stronger behavioural intentions to engage in normative and non-normative collective action for gender equality, whereas among men it would predict weaker intentions to engage in both types of collective action. We also predicted that national narcissism should be related to lower support for normative and non-normative collective action among men and women. As a robustness check, we compared the patterns of predictions for national narcissism and gender collective narcissism to the patterns of predictions for national ingroup satisfaction and gender ingroup satisfaction.

We pre-registered our hypotheses and analytical strategy using multiple regression to (1) test the unique contributions of national narcissism and gender collective narcissism and (2) perform the robustness test adding national and gender ingroup satisfaction as covariates. Following the recommendations by Simmons et al. (2011), we first tested the hypotheses without and then with the covariates. For the sake of brevity, we report only the latter analyses. Analyses without covariates support the hypotheses and can be viewed in Tables S2 and S3 and Figure S1 in the online supplement.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 1075 Polish adults (567 women and 508 men, age ranged from 18 to 86 years; Mage = 45.10; SD = 16.03) collected by the Ariadna Research Panel (http://www.panelariadna.com). The sample is nationally representative in terms of age, gender, and place of residence. Participants were sampled from a pool of 80,000 respondents. Participants in Study 1 could not take part in Study 2. There were no missing responses in this dataset. Demographic questions were presented first, then the study measures were completed in random order for each participant with the order of items within measures also randomised for each participant.

A priori sample size estimations were carried out using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009). To test and specify H1, we estimated a sample size required for a multiple regression analysis with nine predictors: gender, national narcissism, gender collective narcissism, national ingroup satisfaction, gender ingroup satisfaction and all two-way interactions of aspects of ingroup evaluation with gender. For the association between gender collective narcissism and support for collective action, we entered f2 = 0.20 based on previous results regarding the association between men’s gender collective narcissism and solidarity with women protesting anti-abortion laws in Poland (Górska et al., 2020). For 80% power at α = .01 (as multiple outcomes were analysed), the required sample was, N = 55. We followed the recommendations by Giner-Sorolla (2018) and doubled this sample size, as we expected a cross-over interaction. Thus, the sufficient sample size to test H1 was N = 110.

To test H2, where we expected a main effect in the same multiple regression analysis, we entered f2 = 0.075 for the association between national narcissism and support for collective action, based on previous research on sexism (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021). The required sample size was N = 143. Finally, to test and specify H3, we estimated a sample size required for a multiple regression analysis with 5 predictors: gender, gender collective narcissism, gender ingroup satisfaction, their two-way interactions and national ingroup satisfaction as a covariate. We entered a moderate effect size f2 = 0.20. For 80% power at α = .05, the required sample was N = 42. We multiplied this sample size by 14 due to the expected shape of the interaction (Giner-Sorolla, 2018). The required sample to test H3 was N = 588.

Measures

The same measures for national narcissism, gender collective narcissism, national ingroup satisfaction, and gender ingroup satisfaction from Study 1 were used in Study 2. Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which they agree with each item using a scale ranging from 1 (“definitely not”) to 7 (“definitely yes”). Higher scores on all scales indicate a higher degree of the assessed variable.

Support for All-Poland Women’s Strike

Support for All-Poland Women’s Strike was assessed with three items created for this study: “Do you support the All-Poland Women’s Strike?”; “Do you support actions in support of women’s reproductive rights organized by the All-Poland Women’s Strike?” and “Do you take part in actions in support of women’s reproductive rights organized by the All-Poland Women’s Strike?”.

Support for Collective Action for Gender Equality

Support for normative collective action for gender equality was assessed with three items: “I would take part in protests and demonstrations for the equal rights of women”; “I would volunteer to work for organizations for the equal rights of women”, and “I would donate money to organizations acting for the equal rights of women.” Support for non-normative collective action was assessed with four items based on the Activism-Radicalism Intention Scales (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2009): “I would support an organisation that supports equal rights for women, even if it sometimes resorts to violence”; “I would verbally attack politicians who oppose gender equality”; “I would physically attack police if they were violent against protesting women,” and “I would participate in protests against gender inequality even if they were illegal.” The scale was translated to Polish and back-translated by independent bilingual speakers.

Results and Discussion

The zero-order correlations are in Table 5. Among women, gender collective narcissism was positively associated with support for normative collective action, non-normative collective action, and support for the All-Poland Women’s Strike. National narcissism was negatively associated with support for the All-Poland Women’s Strike and normative collective action, but not associated with support for non-normative collective action. Among men, gender collective narcissism was negatively associated with support for the All-Poland Women’s Strike and normative collective action for gender equality but was unrelated to non-normative collective action. The association between national narcissism and gender collective narcissism was positive among men than among women.

Collective Narcissism and Gender Equality

To test and specify H1 and H2, we ran three separate hierarchical multiple regression analyses with each of the three indicators of support for collective action for gender equality as outcomes: intentions to engage in collective action initiated by All Poland Women’s Strike, intentions to engage in normative and non-normative collective action. As predictors, we entered the main effects of national narcissism, national ingroup satisfaction, gender collective narcissism, gender ingroup satisfaction, gender (0 = men, 1 = women), and two-way interactions of gender with national narcissism, national ingroup satisfaction, gender collective narcissism, and gender ingroup satisfaction (for analyses without covariates see Tables S2 and S3 and Figure S1 in the online supplement). All analyses were run in R (R Core Team, 2013). The tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019) was used for data preparation, the sjPlot package (Lüdecke, 2021) for tables and figures, and the interactions package (Long, 2019) for simple slopes analyses. In cases of residual non-normality or heteroscedasticity in regression models, estimates were adjusted for heteroscedastic standard errors (HC3; Hayes & Cai, 2007) using the sandwich package (Zeileis et al., 2021).

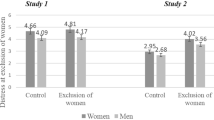

As can be seen in Table 6, in line with H1, for all three indicators of support for gender equality, the interactions between gender collective narcissism and gender were significant. In contrast, gender ingroup satisfaction did not interact with gender to predict any of the outcomes. As illustrated in Fig. 1, and partially in line with H1, simple slopes analyses demonstrated that gender collective narcissism among women was strongly, positively associated with each indicator of support for collective action for gender equality. Among men, the relationships were, contrary to expectations, not significant, except for a weak, positive association with support for radical, non-normative collective action.

As shown in Table 6, in line with H2, among men and women, national narcissism was negatively associated with support for the All-Poland Women’s Strike. However, contrary to expectations, national narcissism was not negatively associated with support for normative or non-normative collective action for gender equality. National ingroup satisfaction did not predict any of the outcomes as a main effect or in interaction with gender.

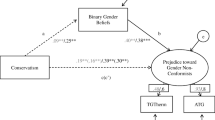

Gender Asymmetry

To test H3, a multiple regression analysis was conducted with gender collective narcissism, gender ingroup satisfaction gender, and two-way interactions of gender with gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction as predictors of national narcissism. Gender ingroup satisfaction and its interaction with gender were included as covariates for robustness check (for analyses without covariates see Table S4 and Figure S2 in the online supplement; for an alternative way to test H3 in path analysis see Figure S3 in the online supplement). The results are presented in Table 7. Consistent with H3, there was a significant gender x gender collective narcissism interaction, with gender collective narcissism more strongly associated with national narcissism among men compared to women (see Fig. 2).

In sum, the results of Study 2 partially supported H1 and H2 with respect to behavioral intentions to engage in normative and non-normative collective action and support for the All-Poland’s Women Strike. Gender collective narcissism (but not gender ingroup satisfaction) predicted behavioral intentions to engage in all forms of collective action for gender equality among women, but not among men. Among men and women, national narcissism predicted weaker intentions to engage in collective action of All-Poland Women’s Strike. The results supported H3 indicating that the association between gender collective narcissism and national narcissism was significantly stronger among men than among women.

Behavioral intentions to engage in collective action involve commitment to political behavior, which is less common than commitment to a political goal (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2009). However, commitment to a political goal suggests a potential involvement in political behavior in the correct circumstances (Thomas et al., 2014). Thus, to understand how national narcissism and gender collective narcissism predict commitment to gender equality as a political goal in Study 3, we examined how national narcissism and gender collective narcissism predict egalitarian worldview vs. political conservatism and blatant legitimization of gender inequality.

Study 3

In Study 3, we test H1 and H2 by examining support for gender equality with three separate indicators: egalitarian worldview, political conservatism, and legitimization of gender inequality. We also replicated the test of H3 from Study 2 in an independent sample of Polish adults. As a robustness check, as in Study 2, we compared the patterns for collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction (national and gender) as predictors of support for gender equality. For analyses without covariates see Tables S5 and S6 and Figure S4 in the online supplement.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were a nationally representative sample of 1084 Polish adults (568 women and 516 men, age ranged from 18 to 80 years, Mage = 45.08; SD = 15.70) collected by the Ariadna Research Panel (http://www.panelariadna.com). Participants from Study 1 and 2 could not take part in Study 3. All samples were independent and collected at different times. The procedure was the same as Study 1 and 2. Relying on the same a priori sample size as Study 1 assessments, we concluded the available sample was sufficient to test H1-H3.

Measures

The same measures for national narcissism, gender collective narcissism, national ingroup satisfaction and gender ingroup satisfaction from Study 1 and 2 were used in Study 3.

Egalitarianism

Egalitarianism was measured with a 3-item critical consciousness scale used in past research (Rapa et al., 2020). Items were: “We would have fewer problems if we treated people more equally”; “It is important to correct social inequalities”; and “All social groups should have equal chances in life.” Items were translated and back-translated to Polish by bilingual speakers for meaning equivalence. Two items of the original 5-item scale were dropped due to weak face validity and maximise scale reliability. Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which they agree with each item using a scale ranging from 1 (“definitely not”) to 7 (“definitely yes”). Higher numbers indicate higher egalitarianism.

Political Conservatism

Political conservatism was assessed through self-placement on a 5-point scale from 1 (conservative) to 5 (liberal). To match the remaining measurements, this item was rescaled to range from 1 to 7 7 using the scales package (Wickham & Seidel, 2022). Higher scores indicated more conservative political outlook.

Legitimization of Gender Inequality

Legitimization of gender inequality was assessed with an 8-item scale used in past research (Kay & Jost, 2003). A sample item is: “Everyone, men and women, have equal chances to achieve wealth and happiness.” Items were translated and back-translated to Polish by bilingual speakers for meaning equivalence. Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which they agree with each item using a scale ranging from 1 (“definitely not”) to 7 (“definitely yes”). Higher numbers indicate higher support for beliefs legitimizing gender inequality.

Results and Discussion

The zero-order bivariate correlations are in Table 8. Among men and women, national narcissism and national ingroup satisfaction were positively associated. Political conservatism was positively associated with legitimization of gender inequality, and both were negatively associated with egalitarianism. Gender collective narcissism and gender ingroup satisfaction were positively associated.

Among women, gender collective narcissism was negatively associated with political conservatism and legitimization of gender inequality, and positively associated with egalitarianism. Among men, gender collective narcissism was positively associated with political conservatism and legitimization of gender inequality, and it was unrelated to egalitarianism. Among men and women, national narcissism and national ingroup satisfaction were positively associated with political conservatism and legitimization of gender inequality. National ingroup satisfaction was positively related to egalitarianism. National narcissism was unrelated to egalitarianism among women and positively related among men.

Collective Narcissism and Gender Equality

As can be seen in Table 9, in line with H1, all interactions between gender and gender collective narcissism were significant.

As can be seen in Fig. 3, simple slopes analysis to probe the significant interactions revealed relationships consistent with H1. Among men, gender collective narcissism was negatively associated with egalitarianism and positively associated with political conservatism, legitimization of gender inequality. Among women, gender collective narcissism was positively associated with egalitarianism and negatively related to political conservatism, legitimization of gender inequality. Those results were specific to gender collective narcissism. Gender ingroup satisfaction did not interact with gender to predict the outcomes. Instead, it positively predicted both, legitimization of gender inequality (also predicted positively by national ingroup satisfaction) and an egalitarian worldview among men and women.

Results presented in Table 9 are consistent with H2. As expected, the associations between national narcissism and political conservatism were positive among men and women. Contrary to expectations, national narcissism interacted with gender to predict legitimization of gender inequality and egalitarianism. Probing those interactions indicated that the results, although unexpected, were consistent with our general argument: the positive association between national narcissism and legitimization of gender inequality and the negative association with egalitarianism were only significant among women but not significant among men (see Fig. 4, middle and right panels).

Specifically, at lower levels of national narcissism, women were less politically conservative, more egalitarian, and legitimized gender inequality less than men. However, this changed as a function of national narcissism. At high levels of national narcissism, women were more likely than men to endorse political conservatism, beliefs that legitimize gender inequality and less likely to endorse egalitarian worldview. National ingroup satisfaction did not show this pattern of associations; it was positively associated with legitimization of gender inequality, but not with the other outcome variables. Thus, the results predicted by H2 are specific to national narcissism.

Gender Asymmetry

In line with H3 and replicating Study 2, there was a significant interaction between gender collective narcissism and gender in predicting national narcissism (Table 10). The results in Fig. 2 (right panel) support H3, replicating the stronger association between national narcissism and gender collective narcissism among men than among women.

In sum, the results of Study 3 supported H1 and H2 with respect to ideological beliefs and commitment to political goal of gender equality. Gender collective narcissism (but not gender ingroup satisfaction) predicted egalitarianism and rejection of political conservatism and beliefs legitimizing gender inequality among women. In contrast, among men, it predicted political conservatism, support for beliefs legitimizing gender inequality and rejection of egalitarianism. National narcissism (but not national ingroup satisfaction) was positively associated with political conservatism, legitimization of gender inequality and lower egalitarianism. The last two associations were stronger among women than among men. Consistent with H3, the association between gender collective narcissism and national narcissism was significantly stronger among men than among women.

General Discussion

We argue that to understand how ingroup identification is implicated in attitudes towards gender equality, it is important to (1) differentiate collective narcissism as an aspect of ingroup identification and (2) consider that men and women simultaneously identify with their respective gender groups and the nation in which those groups are nested. The present results generally support the three pre-registered hypotheses and are largely consistent across variables pertaining to egalitarian ideological outlook and behavioral intentions to engage in collective action for gender equality.

In line with H1, gender collective narcissism is related to support for egalitarian values, rejection of beliefs legitimizing gender inequality and rejection of anti-egalitarian political conservatism among women. In contrast, among men, gender collective narcissism predicts anti-egalitarianism, political conservatism, and endorsement of beliefs legitimizing gender inequality. Also in line with H1, among women, gender collective narcissism predicts intentions to engage in normative and non-normative collective action for gender equality. Among men, contrary to H1, gender collective narcissism was not associated with behavioural intentions to engage in normative collective action (and weakly positively associated with behavioral intentions to engage in non-normative collective action, which is consistent with collective narcissistic general preference for violence and disruption, Golec de Zavala, 2023). Those findings were unique to gender collective narcissism; the measure of gender ingroup satisfaction did not show the same pattern of predictions.

Consistent with H2, among men and women, national narcissism is associated with a refusal to engage in collective action led by the All-Poland Women’s Strike, political conservatism, legitimization of gender inequality and anti-egalitarian outlook. In line with previous research (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021), national narcissism interacts with gender to predict a stronger anti-egalitarian worldview and stronger endorsement of beliefs legitimizing gender inequality among women. At low levels of national narcissism women are more egalitarian than men, but at high levels of national narcissism, women report weaker egalitarian views than men. At low levels of national narcissism, women reject beliefs legitimizing gender inequality more strongly than men, but at high levels of national narcissism, women report similar levels of endorsement of beliefs legitimizing gender inequality. In sum, national narcissism appears to thwart pursuit of gender equality among men, but especially among women. This conclusion is specific to national narcissism. In contrast, national ingroup satisfaction does not predict egalitarian commitment or engagement in collective action for gender equality.

Finally, consistent with H3, the association between gender collective narcissism and national narcissism is stronger among men than among women. This asymmetry is specific to collective narcissism and is not observed for gender ingroup satisfaction and national ingroup satisfaction. This suggests that national narcissism is associated with pursuit of group interests of men rather than women and rejection of gender equality.

Gender Collective Narcissism and Gender Equality

Narcissistic resentment for the lack of appropriate recognition of the superiority of the gender ingroup may seem delusional among men who enjoy power and privilege. However, the same resentment may seem less detached from reality among women who objectively experience discrimination from more powerful men. Nevertheless, results of Study 1 indicate that gender collective narcissism is the same variable among men and women. In both gender groups, we can differentiate gender collective narcissism from gender ingroup satisfaction and establish the expected positive association between them.

Moreover, we can also establish that gender collective narcissism among women and men alike is related to a desire for the ingroup to be better than the outgroup. Indeed, as expected based on collective narcissism theory and previous research, the associations of gender collective narcissism with zero-sum beliefs about gender relations and gender intergroup antagonism were the same among men and women. Gender collective narcissists among men and women alike believed that the gender outgroup threatens the interests of the gender ingroup and should be fought with and dominated even if that meant resorting to violence. Thus, the present results help clarify that gender collective narcissism represents the same narcissistic desire for the gender ingroup to be recognized as better and more special, more important, and more worthy of privileged treatment than the gender outgroup. Yet, for men as the advantaged gender group, this desire aligns with weaker support for gender equality, whereas for women as the disadvantaged gender group, this desire aligns with stronger support for gender equality.

The present results qualify the previous findings indicating that positive ingroup identification predicts positive attitudes towards equality among advantaged and disadvantaged groups (Osborne et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2020). The present results help to clarify that positive attitude towards gender equality is specifically the function of gender collective narcissism among women. The supportive attitude is not predicted by non-narcissistic gender ingroup satisfaction (another aspect of gender ingroup identification) among women. In contrast, gender collective narcissism (but not gender ingroup satisfaction) among men is associated with a negative attitude towards gender equality. Thus, gender collective narcissism predicts a positive attitude towards gender equality only among members of the disadvantaged group, women. This is in line with previous findings pointing to the association between gender collective narcissism and distress and anger at women’s exclusion only among women but not among men (Golec de Zavala, 2022). To the best of our knowledge, these are the first demonstrations of potentially constructive social consequence of collective narcissism (cf. Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020). These findings also help to clarify that at low levels of gender collective narcissism, men may support gender equality even though this means their gender ingroup may lose benefits and privileges.

The present findings also clarify that at high levels of gender collective narcissism women actively challenge the unequal system that harms them. These results align with and extend the social identity model of collective action (SIMCA). This model posits that ingroup identification with the disadvantaged ingroup is not sufficient to motivate collective action for equality. It needs to be accompanied by anger and resentment against the advantaged outgroup and the sense of ingroup efficacy and righteousness of the ingroup goals (van Zomeren et al., 2008, 2018). The present results suggest that all factors contributing to engagement in collective action may constitute collective narcissism as a specific aspect of ingroup identification. The concept of collective narcissism comprises positive ingroup evaluation, a sense of group efficacy, ingroup entitlement, and resentment over the lack of the ingroup’s recognition. The same gender collective narcissism motivates men to protect privileges of their gender ingroup and motivates women to challenge gender inequality. Thus, the same collective narcissistic dynamic operates among advantaged and disadvantaged groups but leads to different outcomes because the goals of those groups are in opposition as far as the pursuit of equality vs. power and privilege is concerned.

The results that gender collective narcissism predicts acceptance of radical and violent actions in the pursuit of gender equality among women is consistent with previous findings pointing to the robust association between collective narcissism (but not ingroup satisfaction) and intergroup antagonism (Golec de Zavala, 2023) and political radicalism (Jasko et al., 2020; Yustisia et al., 2020). Those results suggest that intergroup antagonism and the willingness to fight for the ingroup’s goals may be a necessary aspect of the pursuit of social equality.

The frequent consequences of collective narcissism – intergroup retaliatory hostility (Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020; Hase et al., 2021) and hypersensitivity to insult and intergroup threat (Golec de Zavala et al., 2016) – may potentially undermine the effectiveness of collective action for gender equality. In particular, political radicalism and non-normative collective action can undermine broader public support for the collective action’s cause (Teixeira et al., 2020), yet non-normative collective action can also elicit concessions from the advantaged group and lead to social change towards gender equality when accompanied by an explicitly egalitarian outlook (Shuman et al., 2021). Other research has also shown that while collective narcissistic intergroup antagonism motivates members of disadvantaged groups to challenge inequality sometimes in vehement and intense manners, the typical collective narcissistic hostility may be neutralized by a communal normative context that accompanies pursuit of social equality (Golec de Zavala et al., 2024). Future studies should explore these possibilities.

Collective Narcissism and Obstacles to Gender Equality

The present results identify two obstacles to the pursuit of gender equality: gender collective narcissism among men and national narcissism among men and women. Gender collective narcissism impairs pursuit of gender equality among men. These results align with other research indicating, more broadly, that collective narcissism on the part of advantaged groups (Catholics, men, heterosexuals) is associated with a rejection of collective action for social equality including gender equality, advancement of LGBTIQ + rights, or racial equality (Górska et al., 2020; Keenan & Golec de Zavala, 2024).

The present results also indicate that national narcissism may thwart the pursuit of gender equality. National narcissism was associated with a refusal to engage in collective action led by All Poland Women’s Strike and positively associated with anti-egalitarian conservatism among men and women. Moreover, the patterns of interactions between national narcissism and gender in predicting legitimization of gender inequality and anti-egalitarianism clearly suggest that the more women endorse national narcissism, the more they internalize patriarchal hierarchy that harms their gender ingroup. In comparison to women who endorse national narcissism to a lesser extent, women who endorse national narcissism to a larger extent hold similar negative attitudes towards gender equality as men. Those results align with previous findings indicating that the association between national narcissism and sexism is stronger among women than men (Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021). They also elucidate why members of disadvantaged groups do not universally challenge unequal social systems that oppress them (Brandt, 2013; Caricati, 2018; Jost, 2019; Owuamalam et al., 2018, 2019). Women who endorse national narcissism internalize the national norms which in case of patriarchal societies disadvantage their gender group.

Women who endorse higher levels of national narcissism represent a case of group members who seek external recognition of their national ingroup despite being a socially and economically disadvantaged gender group within that national context. It remains unclear how these positions are reconciled. For example, some women who endorse national narcissism may be exceptionally hostile towards other women, especially those who violate traditional gender norms and those who challenge gender inequality. They may also participate in movements opposing gender equality, like women representing the Polish Life and Family Foundation, a proponent of the “Stop abortion” bill, the most restrictive abortion law penalizing any case of abortion, or women who label proponents of reproductive women’s rights as “fans of killing babies” (Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2023).

The asymmetry in the association between national narcissism and gender collective narcissism among men and women may be related to the fact that gender and national collective narcissism are differentially related to attitudes towards gender equality among women. Given the persistent association between collective narcissism, violence, coercion, and conflict escalation (Golec de Zavala et al., 2019), we interpret this asymmetry to indicate that the projection of masculine values and norms on the national identity is an adversarial strategy to legitimize men’s advantaged position within the national hierarchy. This greater overlap also suggests that overpowering women may become a matter of national importance for some men (Graff & Korolczuk, 2022). Overt hostility of the Polish ultraconservative populist government that uses the state power against the Polish women’s pursuit of equal rights is in line with this interpretation (Human Rights Watch, 2021). It is also in line with the argument that national narcissism that excludes women and sexual minorities is at the heart of the ideological success of the current wave of ultraconservative populism worldwide (Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2021; Golec de Zavala et al., 2021).

The association between national narcissism and gender collective narcissism may be weaker among women because their gender collective narcissism counteracts their internalization of the patriarchal norms and values. The normative prescriptions associated with national narcissism are directly at odds with motivations associated with gender collective narcissism among women. Women who endorse collective narcissism but solve this conflict by embracing their national rather than gender identity may compensate by stronger adherence to the patriarchal norms. The present results are consistent with system justification theory (Jost, 2019), which proposes that members of disadvantaged groups may be motivated to legitimize inequality even more than members of advantaged group. However, the present results suggest that this prediction may need to be specified as limited to those members of disadvantaged group who endorse national narcissism (or collective narcissism with reference to the superordinate category within which the disadvantaged ingroup is nested).

Limitations and Future Directions

Although they provide new insights into social identity processes in pursuit of gender equality, the present studies are not without caveats that need to be considered when interpreting their results. The present results are correlational. Thus, we do not have any evidence that collective narcissism precedes attitudes towards gender equality when we argue that it predicts or motivates them. Our argument is based on the social identity perspective on collective action (e.g., Klandermans, 2014; van Zomeren et al., 2008, 2018), which proposes that the drive to engage in collective action stems from positive ingroup identification with the disadvantaged group. However, other theoretical accounts (e.g., see Sidanius et al., 1997 for social dominance theory; see Jost et al., 2004 for system justification theory) suggest that individual differences in a motivation to maintain social inequality may determine the strength of identification with super- and subordinate ingroups. Thus, future studies using longitudinal and experimental design should determine the directionality of the relationship between collective narcissism and attitudes towards gender inequality. In this vein, emerging longitudinal findings indicate that ingroup identification precedes attitudes towards social inequality among advantaged and disadvantaged groups (Thomas et al., 2020).

Additionally, our studies were conducted in Poland, which raises questions about their generalizability beyond this national context and beyond the specific context of gender inequality. However, findings show that the predictions of collective narcissism with regards to attitudes towards equality differ between advantaged and disadvantaged groups also in the context of racial hierarchy in the UK and the US (Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2023; Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; Marinthe et al., 2022). Nevertheless, future studies would do well to test similar hypotheses within different intergroup and national contexts, and especially whether the predictions of gender collective narcissism generalize to societal context in which the status of men and women is more equal than in Poland. For example, the United States precede Poland in the index of gender equality assuming the 30th place in the recent ranking of 157 world countries (World Population Review, 2022); however gender asymmetry in the association between gender and national identification was also observed in the United States (van Berkel et al., 2017). We expect that this asymmetry is specific to collective narcissism and illustrates the same principle: usurpation of national goals to pursue the gender ingroup goals. However, it is possible that this asymmetry is reduced in countries that normatively pursue gender equality. Further studies should explore whether the gender asymmetry in the strength of the association between gender and national narcissism is dependent on the level of gender equality characterizing different nations as well as national norms favoring pursuit of gender equality.

It is also important to note that the present results are specific to participants who defined their gender in binary terms. Future studies would do well to explore attitudes towards gender inequality among people with non-binary gender identities. Such studies could capitalize on previous research that assessed collective narcissism with reference to non-cisgender and non-hetero-normative group (Bagci et al., 2022).

Practice Implications

The present results indicate that national narcissism is a psychological obstacle to gender equality among men and women. Those results support the argument that efforts to reduce national polarization by re-categorization and enhancing identification with a superordinate, common ingroup may impair the possibility of social change towards equality (Glasford & Dovidio, 2011; Ufkes et al., 2016). This seems to be especially the case when national narcissism is advanced as the way of defining the common national identity. The social change towards gender equality may be enhanced by efforts to change the prevailing discourse about national identity away from a narcissistic desire for its external recognition and toward a non-narcissistic discourse emphasizing internal solidarity, communal values, and interdependence of all co-nationals. Gender collective narcissism among men is another obstacle to pursuit of gender equality. Efforts to de-emphasize narcissistic discourse about male gender identity could focus on non-narcissistic appreciation of inherent value of this social identity independent of intergroup comparisons or external recognition.

Conclusion

In the current research, we differentiated between gender collective narcissism and national collective narcissism as distinct aspects of identification with gender group and nation that may be differentially related to attitudes toward gender equality. Results of three pre-registered studies show that at high levels of gender collective narcissism, men and women approach the pursuit of gender equality as a zero-sum conflict and endorse opposing attitudes towards gender equality. High gender collective narcissism is needed for women to contest unequal system that harm them, but low gender collective narcissism is needed for men to support gender equality. National narcissism is an obstacle to the pursuit of gender equality among men, but also for women who endorse legitimizing beliefs in support of gender inequality. Studies that do not differentiate gender collective narcissism and national narcissism may produce inconsistent findings regarding the role of ingroup identification in system legitimization and collective action among members of disadvantaged groups.

Data Availability

All datasets generated by this project, study materials and codes for analyses can be found at: https://osf.io/rvhyb/

References

Agostini, M., & van Zomeren, M. (2021). Toward a comprehensive and potentially cross-cultural model of why people engage in collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of four motivations and structural constraints. Psychological Bulletin, 147(7), 667–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000256

Bagci, S. C., Acar, B., Eryuksel, E., & Ustun, E. G. (2022). Collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction in relation to collective action tendencies: The case of LGBTI individuals in Turkey. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 29(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM29.1.3

Bagci, S. C., Stathi, S., & Golec de Zavala, A. (2023). Social identity threat across group status: Links to psychological well-being and intergroup bias through collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 29(2), 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000509

Beaujean, A. A. (2014). Latent variable modeling using R: A step-by-step guide. Routledge.

Brandt, M. J. (2013). Do the disadvantaged legitimize the social system? A large-scale test of the status–legitimacy hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(5), 765–785. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031751

Brewer, M. B., Gonsalkorale, K., & van Dommelen, A. (2013). Social identity complexity: Comparing majority and minority ethnic group members in a multicultural society. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16(5), 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212468622

Caricati, L. (2018). Considering intermediate-status groups in intergroup hierarchies: A theory of triadic social stratification. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology, 2(2), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts5.19

Caricati, L., Owuamalam, C., & Bonetti, C. (2021). Do superordinate identification and temporal/social comparisons independently predict citizens’ system trust? Evidence from a 40-nation survey. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 745168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.745168

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Devos, T., Gavin, K., & Quintana, F. J. (2010). Say “adios” to the American dream? The interplay between ethnic and national identity among Latino and Caucasian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015868

Doucerain, M. M., Amiot, C. E., Thomas, E. F., & Louis, W. R. (2018). What it means to be American: Identity inclusiveness/exclusiveness and support for policies about Muslims among US-born Whites. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 17(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12167

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., Ufkes, E. G., Saguy, T., & Pearson, A. R. (2016). Included but invisible? Subtle bias, common identity, and the darker side of “we.” Social Issues and Policy Review, 10(1), 6–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12017

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (2002). Self and social identity. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 161–186. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135228

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Federico, C. M., Golec De Zavala, A., & Bu, W. (2022). Collective narcissism as a basis for nationalism. Political Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12833

Giner-Sorolla, R. (2018, January 24). Powering your interaction. Approaching Significance. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://approachingblog.wordpress.com/2018/01/24/powering-your-interaction-2/

Glasford, D. E., & Dovidio, J. F. (2011). E pluribus unum: Dual identity and minority group members’ motivation to engage in contact, as well as social change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 1021–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.021

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109

Golec de Zavala, A. (2011). Collective narcissism and intergroup hostility: The dark side of ‘in-group love.’ Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00351.x

Golec de Zavala, A. (2022). Conditional parochial vicarious ostracism: Gender collective narcissism predicts distress at the exclusion of the gender ingroup in women and men. Sex Roles, 87, 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01315-z

Golec de Zavala, A. (2023). The psychology of collective narcissism. Routledge.

Golec de Zavala, A., & Bierwiaczonek, K. (2021). Male, national, and religious collective narcissism predict sexism. Sex Roles, 84(11), 680–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01193-3

Golec de Zavala, A., Cichocka, A., Eidelson, R., & Jayawickreme, N. (2009). Collective narcissism and its social consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1074–1096. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016904

Golec de Zavala, A., Dyduch-Hazar, K., & Lantos, D. (2019). Collective narcissism: Political consequences of investing self-worth in the ingroup’s image. Political Psychology, 40(Suppl 1), 37–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12569

Golec de Zavala, A., Federico, C. M., Sedikides, C., Guerra, R., Lantos, D., Mroziński, B., Cypryanska, M., &, Baran, T. (2020). Low self-esteem predicts outgroup derogation via collective narcissism, but this relationship is obscured by ingroup satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(3), 741–764. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000260