Abstract

The current study examined the associations between perceived actual-ideal discrepancies in facial and bodily attributes and adolescent girls’ appearance satisfaction and whether these relationships were moderated by the importance associated with the attributes and/or the country of the participants. A multilingual survey was completed by 900 girls aged 12–18 years old living in Australia, China, India, and Iran. Girls in India and Iran were most satisfied with their appearance followed by girls in China and Australia. Iranian girls had the highest perceived actual-ideal discrepancies in facial and bodily attributes. Chinese and Indian girls perceived their facial attributes to be more important to their overall sense of appearance than their bodily attributes, whereas Australian and Iranian girls valued them equally. Higher perceived actual-ideal facial discrepancies were related to lower appearance satisfaction only for Iranian girls and higher perceived bodily discrepancies were linked to lower appearance satisfaction only for Australian girls. The importance associated with physical attributes and/or the country of participants did not moderate the relationship between perceived discrepancies and appearance satisfaction for facial or bodily attributes. Findings underscore the critical role of cultural nuances in understanding body image among adolescent girls and determinants of appearance satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Appearance dissatisfaction can develop early in life and is prevalent among individuals living in diverse world regions (Gattario & Frisen, 2019; Jaeger et al., 2002; Swami et al., 2010; Wardle et al., 2006). These concerns have been reported to be higher among girls and women than their male counterparts (Grogan, 2021; Quittkat et al., 2019). Understanding the factors contributing to appearance concerns in adolescent girls is crucial, as negative body image can be detrimental to their emotional and physical well-being (Bornioli et al., 2019, 2020; Stice & Shaw, 2002). Cross-cultural knowledge in particular, can enhance our understanding of how attitudes related to appearance manifest among girls from different countries. Since socialization practices can differ significantly across diverse settings, varied attitudes regarding their bodies may arise. This understanding is essential to develop culturally appropriate body image intervention programs that are better aligned with the appearance-related experiences of girls from different cultural backgrounds.

One of the many factors that may influence appearance dissatisfaction is perceived discrepancies between how a person see themselves right now (actual self) and how they wish or want to look (ideal self; Jacobi and Cash, 1994). The appearance ideals promoted in various parts of the world are often narrow and unattainable for most people (Grogan, 2021; Thompson et al., 2012). For adolescent girls, growing up in an environment replete with unrealistic beauty ideals will likely result in a perceived discrepancy between their actual and ideal appearance (Halliwell & Dittmar, 2006), which could result in more appearance dissatisfaction, especially when great importance is placed on physical appearance (e.g., Carey et al., 2011).

Further, some physical attributes may be more salient to certain cultural groups than others (Frederick, Reynolds et al., 2022; Jackson and Chen, 2008; Yip et al., 2019). Therefore, the values placed on certain physical attributes within particular cultural settings may influence the degree to which perceived actual-ideal discrepancies emerge for those attributes and in turn, differentially contribute to an individual’s sense of appearance satisfaction in those cultures. This possibility has yet to be tested within the body image literature, especially cross-culturally. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine perceived facial and bodily actual-ideal discrepancies, the importance of facial and bodily attributes, and appearance satisfaction among adolescent girls in Australia, China, India, and Iran. Specifically, we tested if the association between perceived appearance discrepancies and appearance satisfaction is moderated by the importance associated with those attributes and the cultural context.

Culture and Appearance Dissatisfaction

Cross-cultural studies examining appearance satisfaction among adults and adolescents have found mixed results (Brockhoff et al., 2016; Gramaglia et al., 2018; Holmqvist & Frisen, 2010; McCabe et al., 2012; Mellor et al., 2013, 2014; Swami et al., 2010; Wardle et al., 2006). One line of research suggests that girls and women in affluent Western cultures experience higher appearance dissatisfaction than girls and women from some less affluent non-Western contexts (Holmqvist & Frisen, 2010; Jaeger et al., 2002; Swami et al., 2010). One study across 12 different countries including India found that young women living in affluent Western countries across Europe were very dissatisfied with their bodies, but girls from less-affluent non-Western countries like India were not (Jaeger et al., 2002).

In contrast, some studies have offered support for the notion that Asian people are actually more dissatisfied with their bodies than people from Western countries. For example, a cross-country comparison of 12–19-year-old girls from Australia, China, and Malaysia demonstrated that girls from China and Malaysia reported lower levels of appearance satisfaction than their Australian counterparts (Mellor et al., 2013). Similarly, a study comparing adolescents across six different countries including China, Australia, and Japan concluded that Japanese adolescents reported higher levels of dissatisfaction than girls from Australia and China (Brockhoff et al., 2016). Finally, some researchers have found no group differences in levels of appearance satisfaction across diverse country groups. A study of more than 4,000 adolescents across eight countries including Australia, China, and Malaysia, reported strong cultural similarities in their levels of body satisfaction (McCabe et al., 2012). Further research is needed to examine rates of appearance dissatisfaction among diverse countries and potential predictors of those concerns, including perceived actual-ideal discrepancies.

Considering the reviewed literature on appearance satisfaction across different cultural contexts, it is important to acknowledge the complexities of categorizing individuals solely based on Western or Asian backgrounds. While these terms have often been used to describe people with ancestry in the West/European regions and those native to or with ancestry from Asia, which includes but is not limited to countries like China, India, Japan, Korea, they fail to capture the true diversity within these regions. For instance, despite Asia’s vast geography and diverse cultural customs, shared values such as collectivism, and respect for tradition are prevalent across many societies. However, we recognize that the literature has deemed such categorisations alongside that of other terms (e.g., non-Western) as limiting as it holds the risk of oversimplifying diversity, and awaits an internationally agreed-upon terminology in the realm of cultural research (Bakhshi, 2011; Bhopal & Donaldson, 1998; Bhopal, 2004; Bhopal et al., 1991).

Discrepancies between Actual and Ideal Physical Attributes

One theory that has been influential in contributing to our understanding of body image, despite not being specifically designed to address appearance concerns, is derived from Higgins’ self-discrepancy theory (SDT), which explores the relationship between self-perception and affective experiences. The fundamental premise of SDT revolves around the idea that individuals possess multiple self-representations, including the actual self (i.e., one’s own belief and perception about the self), and the ideal self (i.e., the qualities and attributes that an individual aspires to possess or believes others would like them to possess; Higgins, 1987; Higgins, 1989). Perceiving a discrepancy between one’s actual self and desired self-image can result in negative emotional and physical experiences, including heightened dissatisfaction, lower self-esteem, and increased symptoms of depression and anxiety (for a meta-analysis of self-discrepancy and psychopathology see Mason et al., 2019). While SDT primarily focuses on self-concept, individuals may also perceive discrepancies across different domains, including their appearance, extending the relevance of SDT to appearance-based research. In the context of body image, most research on perceived appearance discrepancies operationalizes appearance concerns as a discrepancy between an individual’s own beliefs, attitudes and perception of their current physical attributes, (i.e., their perceived actual self) and how they would like to be (i.e., their ideal self; Higgins, 1987; Higgins, 1989; Higgins et al., 1985; Kowner, 2004; Szymanski & Cash, 1995). These perceived appearance-based discrepancies can significantly impact an individual’s overall health, leading to lower levels of psychological well-being, increased body image concerns, and the development of unhealthy eating habits (Mason et al., 2019; Solomon-Krakus et al., 2017).

In some research, the magnitude of the discrepancy between an individual’s perceptions of their actual attributes and their ideal attributes serves as a reliable index of their appearance dissatisfaction (Vartanian, 2012). These perceived appearance discrepancies have been examined in a variety of cultural contexts, including among adolescent girls and young women in Australia (Wertheim et al., 2004), China (Fan et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2022), India (Nagar & Virk, 2017), and Iran (Garrusi & Baneshi, 2017). Such approaches have employed different visual depiction techniques (e.g., silhouette drawings of women with different body shape and sizes) to determine the magnitude of weight, shape, and size discrepancy. Regardless of their methodology and origin of culture, these studies have broadly concluded that girls and women tend to endorse a thinner ideal body than their actual body (for a review see Vartanian, 2012).

Another line of research has examined the relationship between the magnitude of an individual’s perceived appearance discrepancy and their appearance dissatisfaction in diverse cultures. One study with 135 White participants from the United States found that perceived actual-ideal discrepancies in body size, weight, muscularity, height, breast size, and hair colour were linked to lower satisfaction with appearance among women (Jacobi & Cash, 1994). Another examination of Caucasian young adults living in the United Kingdom found that greater perceived actual-ideal discrepancies for physical attributes were associated with lower appearance satisfaction (Halliwell & Dittmar, 2006). It is worth noting that the term “Caucasian” has been used to accurately present the terminology used by Halliwell and Dittmar (2006). However, we recognize that the literature has identified its use as problematic and obsolete because it refers to individuals from the Caucasus mountains but is often used to describe White people of European ancestry who are not from this area (Mukhopadhyay, 2018; Saini, 2019; Teo, 2009). Similarly, another study conducted with Japanese undergraduates found that actual-ideal discrepancies in weight, muscularity, and height relate negatively to overall appearance satisfaction (Kowner, 2004). Moreover, this study also found that higher discrepancies in skin colour and nose-related attributes were associated with lower face esteem for Japanese women (Kowner, 2004).

Findings from these studies broadly suggest that actual-ideal discrepancies on a variety of facial and bodily attributes correlate negatively with appearance satisfaction (Halliwell & Dittmar, 2006; Jacobi & Cash, 1994; Kowner, 2004). As part of self-discrepancy theory, Higgins acknowledged that principles of the theory may only be applicable under certain situations depending on the extent and relevance of the discrepancies (Higgins, 1999). This raises interesting possibilities about the processes by which the relationship between ideal-actual discrepancies and appearance satisfaction may vary between different cultural groups, which may pertain to the importance placed on different aspects of appearance.

Importance of Facial and Bodily Attributes

A growing volume of research over the years has highlighted the need to examine various aspects of facial and bodily attributes among individuals with diverse cultural backgrounds (Frederick et al., 2016; Frederick, Pila, et al., 2022; Jones, 2001; Pope et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2019; Swami, Furnham, et al., 2008; Swami, Rozmus-Wrzesinska, et al., 2008). An examination of physical attractiveness ratings for Asian, White, and Hispanic adults showed that all three groups were equally influenced by facial features (Cunningham et al., 1995). In addition, a study on adolescent girls living in Australia, China, and Malaysia found no group differences in their levels of facial dissatisfaction. Surprisingly, dissatisfaction with the face was only associated with overall body dissatisfaction for Australian girls but not Chinese girls (Mellor et al., 2013). Additionally, the study found that Chinese girls reported significantly higher dissatisfaction than Australian girls with respect to weight (weight, shape, muscles; Mellor et al., 2013). These findings contradict past research that suggests that East Asian women may not place as much emphasis on their weight and shape relative to Western women (Chen & Swalm, 1998), but importantly also highlights the salience of facial attributes for Western groups (Mellor et al., 2013).

Despite this evidence, it is commonly perceived that Western and Asian cultural groups differ in the importance they place on different facial and bodily attributes. Scholars have suggested that some non-Western cultures, particularly Asian cultures (e.g., China, Korea, India) place heavy emphasis on facial features relative to bodily attributes (Samizadeh, 2022; Samizadeh & Wu, 2018; Yip et al., 2019). In fact, popular media platforms within Asian cultures such as China, have routinely placed more importance on facial beauty whereas Western media has been known to be more body focused (Grogan, 2021; Jackson & Chen, 2008; Mills et al., 2017; Samizadeh & Wu, 2018).

In line with this difference, some research has suggested that dissatisfaction associated with face, hair, and skin features are particularly salient to body image among people of Asian origin (Chan & Hurst, 2022; Frederick et al., 2016; Frederick, Reynolds, Frederick et al., 2022a, b; Harper and Choma, 2019), indirectly highlighting the importance of facial features for some cultures. This was also evident in a recent study of more than 11,000 adults from different racial groups within the United States which found that people of Asian origin were the most dissatisfied with their own faces as compared to all other racial groups (White, Hispanic, Black; Frederick, Reynolds, Frederick et al., 2022a, b). However, the proposition that certain cultural groups place different degrees of importance on facial and bodily attributes remains to be directly examined among adolescent girls, especially cross-culturally. If this were to be true, then the importance placed on different facial and bodily features by girls within different cultural contexts could influence the association between actual-ideal discrepancies for a physical attribute and their appearance satisfaction.

The Present Study

In light of the gaps in literature, the present study aimed to: (1) investigate the relationship between perceived facial and bodily actual-ideal discrepancies and appearance satisfaction across four countries (i.e., Australia, China, India, and Iran), (2) explore whether the importance associated with facial and bodily attributes moderates the relationship between perceived discrepancies and appearance satisfaction, and whether this relationship varies across country of residence (Australia, China, India, and Iran; see Fig. 1), and (3) examine how adolescent girls from Australia, China, India, and Iran differ in their levels of appearance satisfaction, perceived actual-ideal discrepancies for facial and bodily attributes, and the personal importance of those attributes.

The four countries examined in this study are different with respect to their cultural ethos, ethnic make-up, spoken languages, religious ideologies, degree of affluence, rate of development, internal heritage and traditions, gender roles, as well as their exposure to Western media and lifestyle. For example, Australia is a developed, individualistic society with a predominant European ancestry, but constitutes a variety of cultural groups (including people from Indian, Chinese, and Middle Eastern origins) where most have a Western lifestyle, and speak English as a first or other language (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021a, 2021b; Holmqvist and Frisen, 2010). According to the 2021 Global Gender Gap Report by the World Economic Forum, Australia was ranked 50th out of 156 countries (World Population Review, 2022c). Unlike the other three countries in the present study, Australia’s proximity to the coast frequently exposes women and young girls to the beach body culture, which can create pressure to conform to a physically fit and toned physique (Field et al., 2019; Small, 2017).

China is the most populous country in the world, and ranks 107th out of 156 countries in terms of gender equality (World Population Review, 2022a, 2022c). It is home to 56 ethnically diverse cultural groups, with the Han Chinese constituting over 92% of its entire population (Gustafsson et al., 2020). Although Mandarin is the official dialect of China, people also communicate in their respective local dialects (e.g., Cantonese). Additionally, while many Chinese people can speak English, it is more common among individuals living in urbanized cities (Koyfman, 2018; Li & Thompson, 1989). China is a traditionally collectivistic society in East Asia, and although one of the economically richest countries in the world, it is still classified as a developing nation, and is gradually mirroring traits of an individualistic culture (Hofstede, 2018; Statista, 2022b; United Nations, 2019). Over time, Chinese culture has undergone a transition in its attitudes towards feminine beauty. While Confucian ideologies emphasized feminine beauty, Maoist cultural criticism took a contrasting approach, discouraging it and promoting a simple and modest dressing style for women (Fu & Wang, 2015; Ip, 2003). Confucianism and Maoism are important philosophical and political ideologies in Chinese history. Confucianism emphasizes the importance of social order, hierarchy, and the cultivation of personal virtues, including feminine beauty. Maoism, on the other hand, emerged in the 20th century under the leadership of Mao Zedong and was characterized by strict control over all aspects of society, including cultural expression. Nevertheless, modern Chinese culture greatly values the appearance of girls and women (Ma, 2022; Yang, 2017). Despite having laws that restrict foreign (e.g., Western) media content (Tai & Fu, 2020; Xu & Albert, 2014), Chinese girls are known to be heavily influenced by Western beauty standards (e.g., Jung, 2018).

India is a rich multicultural country with a strong internal heritage that has long been exposed to foreign beliefs and values from its history of British rule (Chen et al., 2020; Majidi, 2020). Although the Indian subcontinent is also linguistically diverse, English, and Hindi are considered the official languages (The Official Languages Act, 1963). It is one of the fastest growing economies in the world, and has an unrestricted exposure to global (e.g., Western) media influences and appearance standards. Despite the impact of globalization and its gradual social growth over the years, Indian society is considered gender unequal and enforced by patriarchal laws, customs, and rituals and ranks 139th out of 156 countries in terms of gender equality (Singh et al., 2022; World Population Review, 2022c). More recently, like China, Indian culture is also showcasing traits of both collectivism and individualism (Hofstede, 2018). Relatedly, some scholars have suggested that in collectivistic societies like China and India, individuals seek behavioural autonomy as well as the need for relatedness at the same time (Kagitcibasi, 1996, 2017).

The Islamic Republic of Iran is rooted in patriarchy and religion (particularly Shia Islam; Ahmadi et al., 2018; Price, 2001). Persian, referred to as Farsi by native Iranians, is the official language of modern-day Iran and the Islamic religion (Levy, 2012). Since the Islamic revolution in 1979, the country mandated strict codes of behaviour and dressing norms for girls and women, with all girls over the age of nine expected to wear a “hijab,” a one-piece head scarf, concealing their hair, neck, and ears, but leaving their face and hands visible in public (Harcet, 2008; Harkness, 2019; Talk, 2022). Girls and women are only allowed to be seen without these coverings by their close male relatives, and in the case of married women, by their husbands (Price, 2001). However, despite being legally mandated, and enforced with penalties, the practice of wearing a hijab, is not universally accepted by all Iranians and Muslims, and not wearing the hijab is often seen as a form of resistance against gendered oppression, a means of asserting personal and political beliefs or rejecting patriarchal control over their bodies (Babakhani, 2022; Rashid, 2023). Iran ranks 149th out of 156 countries in terms of gender equality and consequently has been identified as one of the least gender-equal countries in the world (World Population Review, 2022c). Like China, Iran also has government restrictions limiting foreign influences, but there is a growing presence of Western media influencing the appearance culture within Iran (Aryan et al., 2013; Shoraka et al., 2019).

Based on the tenets of self-discrepancy theory, and the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized the following:

-

1)

Higher perceived actual-ideal discrepancies in facial and bodily attributes would be negatively associated with appearance satisfaction in all countries.

-

2)

The association between actual-ideal discrepancies and appearance satisfaction would be moderated by the level of importance attributed to those ideals, and this moderated effect would vary across the four countries (Fig. 1). Specifically, in a culture where bodily and facial features are highly valued, we predict that the relationship between actual-ideal discrepancy and appearance satisfaction will be stronger among individuals who perceive these attributes as more important.

-

3)

Adolescent girls across Australia, China, India, and Iran would differ in their perceived actual-ideal discrepancies in facial and bodily attributes, the importance they associate with those attributes, and their levels of appearance satisfaction. Given that the cross-cultural literature regarding which group is more dissatisfied with their appearance is largely inconsistent, no specific hypothesis was made pertaining to this particular test.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 900 female participants from Australia (n = 184), China (n = 293), India (n = 223), and Iran (n = 200) with an age range of 12–18 years. Nine schools volunteered their involvement based on contact from researchers across Australia (n = 2), China (n = 2), India (n = 3) and Iran (n = 2). The Australian sample was recruited from schools in Sydney and Lismore located in the state of New South Wales. For India, participants were recruited from schools in the capital region of New Delhi. The Chinese sample was recruited from the Fuzhou region within the Fujian Province in Southeast China. For Iran, data was collected from schools in Isfahan city, located in central Iran. All research sites were located in urban areas within the four countries. Descriptive summaries of the demographic information are presented in Table 1.

Materials

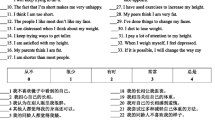

Actual-Ideal Discrepancies in Facial and Bodily Attributes

The discrepancy subscale of the Body Image Ideals Questionnaire (BIQ) was used to measure participants’ discrepancy between their own perceived appearance compared with their perceived ideal for appearance (Cash & Szymanski, 1995). Participants were asked to consider how much they resemble their personal physical ideal (“how they wish or prefer to be”) for ten different facial and bodily attributes, namely: (1) facial features, (2) skin complexion, (3) hair texture and thickness, (4) height, (5) muscle tone and definition, (6) body proportion, (7) weight, (8) chest size, (9) physical strength, and (10) physical coordination. The response options for “how they wish or prefer to be” ranged on a scale from 0 (exactly as I am) to 3 (very unlike me). Higher scores indicated greater discrepancy in perception between actual and ideal facial and bodily attributes.

To assist categorizing these attributes into relevant sub-groups of interest, the ten items in the physical discrepancy subscale were subjected to factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 1854.92, df = 45, p < .001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.831) were significant, suggesting the data was suitable for structure detection. A principal component analyses was therefore conducted using varimax (orthogonal) rotation, and the number of factors to be extracted was determined both by factor eigenvalues above 1.0 and inspection of the scree plot (Cattell, 1966). Based on these criteria, three factors were extracted, which explained 44.90% of the total variance. The first factor included height, muscle tone and definition, body proportions, weight, and chest size (eigen value = 3.71, accounting for 15.65% of the variance; factor loadings = 0.68-0.70). The second factor included facial features, hair texture and thickness, and skin complexion (eigenvalue = 1.20, accounting for 14.98% of the variance; factor loadings = 0.56-0.59). The third factor included physical development and physical coordination (eigenvalue = 1.01, accounting for 14.26% of the variance; factor loadings = 0.62-0.87). Because physical development and physical coordination are not relevant to the appearance of one’s body, these two attributes were removed from subsequent analyses.

Consequently, two categories of facial and bodily features were retained. We therefore calculated two composite discrepancy scores, one for facial attributes (mean ratings of facial features, skin complexion, hair texture and thickness) and the other for bodily attributes (mean ratings on height, muscle tone and definition, body proportion, weight, and chest size). In line with recent recommendations, reliability for all measures was assessed using the OMEGA macro as it is less impacted by the number of scale items than alpha (Hayes & Coutts, 2020). In the current sample, McDonald’s ω for facial discrepancy was 0.62 for Australia, 0.61 for China, 0.70 for India, and 0.55 for Iran. For the bodily discrepancy subscale, McDonald’s ω were 0.76 for Australia, 0.69 for China, 0.75 for India, and 0.68 for Iran.

Importance of Facial and Bodily Attributes

To evaluate the importance participants associated with facial and bodily attributes, the importance subscale of the Body Image Questionnaire was used (Cash & Pruzinsky, 1990). Participants rated how important their physical ideal was for them, with respect to the same eight features listed above, ranging from 0 (not important) to 3 (very important), and were categorised in the same manner described above (facial and bodily attributes). Mean ratings of these features yielded scores for both facial and bodily importance, with higher scores indicating greater personally rated importance of those attributes. Acceptable internal consistency was established using McDonald’s ω for importance of face-related features (Australia = 0.79; China = 0.79; India = 0.84; Iran = 0.70), as well as importance of bodily attributes (Australia = 0.79; China = 0.74; India = 0.79; Iran = 0.72).

Appearance Satisfaction

Participants’ overall appearance satisfaction was measured using the 10-item appearance subscale of the Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (BESSA; Mendelson et al., 2001). Girls indicated their agreement with 10 statements pertaining to their overall appearance (e.g., “I like what I look like in pictures”) on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with higher scores indicating greater general satisfaction with one’s appearance. The Appearance subscale has demonstrated good psychometric properties among adolescent girls (Kling et al., 2019; Mendelson et al., 2001). Adequate internal consistency was recorded in the present study. McDonald’s ω for appearance satisfaction scores in the present study were 0.94 for Australia, 0.61 for China, 0.89 for India, and 0.80 for Iran.

Procedure

The data reported in this article were collected between July 2018 and August 2020, as part of a broader programme of research. Approval was provided by the first author’s University Human Research Ethics Committee, and subsequently by all relevant educational ethics committees across the sites. The survey was translated and administered in three languages: English (Australia and India); Chinese (China); and Persian (Iran). While both Hindi and English are official languages of India, to ensure comparability with other countries in the study, our recruitment was mainly focused on urban areas, where English is often the preferred language of instruction in schools (Trines, 2018). The back-translation technique (Brislin, 1970) was used for the study, in which bilingual members of the research team from China and Iran translated the English version of the survey in Chinese and Persian, respectively. This was followed by recruiting independent research assistants proficient in Chinese and Persian who back-translated the surveys to English. Inconsistencies that emerged during this process were resolved with agreement between the delegated team of translators.

Recruitment of schools and participants at each site followed similar procedures. As determined by the relevant local ethics committee, schools provided initial overall consent and then flyers were sent to parents for their consent. Subsequently, grade-wise administration was scheduled for the study during school hours, for which girls also provided their individual consent before starting the survey. In all research sites, participants were informed regarding the anonymous nature of the survey and were given the option to skip any sensitive questions or discontinue the survey at any time.

Australian girls completed the study online using the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and within Indian schools, both online and the hard-copy versions were used for administration. In China and Iran, the study was administered using the hard copy version of the study. The study took approximately 35 min to complete. In addition to the body image ideals questionnaire and body esteem scale, and other measures related to body image, participants reported on their age, weight (kg), height (cm), country of residence, country of their birth, and ethnicity. To assess participants’ perceived income group, they were asked “To what income group do your parents belong in the community in which they live.” A list of the response options appears in Table 1. As an incentive, participating schools in Australia and India were provided with a report on the mean results of their students and girls who participated were given chocolates as gratitude for their involvement in the study.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 28; IBM Corp, 2021). We first examined histograms, q-q plots, boxplots, skewness, and kurtosis statistics, and found that all variables were approximately normally distributed and had no significant outliers. Participants in each country were then compared on all study variables. When Levene’s test of equality of variances was significant (p < .05), the Welch-Satterthwaite adjustment was reported as this measure is robust to unequal variances and sample size. From the total data, the percentage of missing data was fewer than 6% for the main study variables, less than 8% for the demographic categorical variables and 14% for height and weight. As determined by Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) analyses (Little, 1988), we could not reject the null hypothesis that the data were missing completely at random (χ2 = 186.69, df = 160, p = .073). Since the statistical analyses planned for the study would have used different methods to handle missing data by design (e.g., listwise deletion for moderation analyses), in order to retain the full sample size throughout, a decision was made to replace the missing values. Given that multiple imputation yields moderately robust estimates of missing values, we replaced missing values using pooled estimates from multiple imputations for all subsequent analyses (Rubin, 1988).

To test for between country differences, participants’ demographic variables were examined using ANOVA and chi-square tests. Analyses were then conducted to (a) examine group differences in actual-ideal discrepancy of facial and bodily attributes, importance associated with facial and bodily attributes, and overall appearance satisfaction, (b) investigate the relationships between the aforementioned variables across different cultures, and (c) test the potential moderating roles of country of residence and importance associated with facial and bodily attributes on the relationship between discrepancy of facial and bodily attributes and appearance satisfaction. Group/country differences in the study variables were investigated using ANCOVA and associations were assessed using partial correlations all controlling for participants’ age. To examine if facial discrepancies and importance associated with these features are significantly greater than bodily attributes within each culture, we used a repeated measures ANCOVA. When Mauchley’s test of sphericity was significant (p < .05), the Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment was reported. The Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) was used to examine post-hoc differences between perceived discrepancies in, and importance of, facial and bodily attributes within each country.

To examine if the magnitude of the moderating effect of importance of bodily and facial features on the relationship between discrepancy and appearance satisfaction of adolescent girls differs by country, a moderated moderation model was used. Using PROCESS Macro (Model 3; Hayes, 2018), two identical moderated models were used, one for facial attributes, and another for bodily attributes, to assess the three-way interaction among discrepancy, importance, and country. A conceptual model of these analyses are presented in Fig. 1. For both of the models described below, age was entered as a covariate. Appearance satisfaction was identified as the outcome variable (Y), the focal predictor was perceived actual-ideal discrepancy in facial/bodily attributes (X), importance assigned to facial and bodily features facial/ bodily was the primary moderator (M), and country was the secondary moderator (W). Given that the secondary moderator (country) had four categories (Australia, China, India, and Iran), all countries were dummy coded in the analyses. Since PROCESS is not designed to provide output for all possible comparisons, countries were coded in a way that each group served as a baseline category for the analyses. The analyses were conducted with bias-corrected bootstrapping (n = 5000) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Lastly, given the large number of analyses in the present study, the critical alpha value was adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995), with a false discovery rate of 5%. The adjusted p-value was 0.023.

Results

Between Country Differences on Demographic Variables

Results of comparisons by country on the demographic variables are presented in Table 1. ANOVAs revealed significant between country differences for age (moderate effect), height (moderate effect) and weight (large effect). Post-hoc analyses (Unequal variances: Games Howell for age and height and Tukey’s for weight) indicated that girls in Iran were significantly older than girls from all other countries and Australian participants were taller and heavier than all other groups. Chi-square tests also showed significant differences between country, ethnicity, and the income group of parents. A decision was made to only control for age in the remaining analyses and not for height and weight, since differences in physical characteristics like height and weight are strongly correlated with differences in ethnicity, and controlling for them can likely suppress any cultural effects (Holmqvist & Frisen, 2010). For example, researchers over time have suggested that BMI may be more relevant to consider when examining people from the same cultural group than cross-culturally since the mean BMI for certain cultural groups (e.g., North America) are higher than those within Asia (World Health Organization, 2003), and can lead to misinterpreting body image related constructs.

Between Country Differences on Study Variables

In line with our third hypothesis, there were significant between country differences for all variables (see Table 2). Girls in Iran scored highest on facial discrepancies, followed by girls in India, then girls in Australia and China. Similarly, girls in Iran reported the highest levels of bodily discrepancies, followed by girls in China, then girls in Australia and India. As seen in Table 2, both facial and bodily features were significantly more important to girls in China, Australia, and India than to girls in Iran. Iranian and Indian girls reported higher appearance satisfaction than girls in China and Australia. Girls in Australia reported lower appearance satisfaction than girls in all other countries.

Within Country Differences in Discrepancies and Importance Associated with Facial and Bodily Attributes

There were significant differences between facial and bodily discrepancies and the importance attached to facial and bodily features within each country. As seen in Table 2, perceived actual-ideal discrepancy in bodily attributes was significantly higher than facial attributes for girls in Australia, China, and India. For girls living in Iran, no significant differences were found between bodily and facial discrepancies. For Indian and Chinese girls, the importance associated with facial features was significantly higher than the importance associated with bodily features. Girls living in Australia and Iran did not significantly differ in regard to the importance they placed on facial and bodily attributes.

Country-Wise Correlations Between Discrepancies in Ideals, Importance of Those Ideals and Appearance Satisfaction

With respect to the first hypothesis, which predicted that higher perceived actual-ideal discrepancies would be associated with lower appearance satisfaction, our results provide partial support. As illustrated in Table 3, the perceived discrepancy in facial attributes was negatively associated with appearance satisfaction only for girls in Iran, whereas discrepancy in bodily attributes was negatively associated with appearance satisfaction only for Australian girls. Our results showed no evidence of a relationship between discrepancy and appearance satisfaction for Indian and Chinese girls for either facial or bodily attributes. Moreover, the importance associated with facial and bodily attributes was not significantly correlated with appearance satisfaction within any of the four countries.

As reported in Table 3, the discrepancy in facial attributes was significantly associated with the discrepancy in bodily attributes for girls in Australia, China, and India, but not for girls in Iran. The discrepancy in facial and bodily attributes was significantly correlated with importance associated with those features for girls in Australia, China, and India, but not for participants in Iran. The importance associated with facial features was positively and significantly associated with importance of bodily attributes for all countries.

Testing for Moderated Moderation

As seen in Table 4, contrary to our second hypothesis, there were no significant two-way interactions between discrepancy and the importance for facial or bodily features. The two-way interactions between discrepancy for facial or bodily features and country on appearance satisfaction were also non-significant. In addition, most two-way interactions between the importance of facial and bodily attributes and country on appearance satisfaction were not significant. The only exception was that the relationships between both facial and bodily attributes and appearance satisfaction were negative for girls in India and positive for girls in China. Lastly, the three-way interactions between discrepancies, importance, and country on appearance satisfaction were not significant in the facial or bodily attribute models.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to (a) examine the relationships between actual-ideal discrepancies for facial and bodily attributes and appearance satisfaction, (b) investigate whether the importance associated with facial and bodily attributes and country of residence would moderate those relationships (see Fig. 1), and (c) compare levels of the study variables across Australia, China, India, and Iran. Findings revealed that the relationship between perceived actual-ideal discrepancies in facial attributes and appearance satisfaction was significant only for Iranian girls, while perceived actual-ideal discrepancies in bodily attributes were linked to appearance satisfaction only among Australian adolescents. The association between perceived physical discrepancies and appearance satisfaction were not moderated by the importance associated with those attributes and/or participants’ country of residence. Mean comparisons between girls in the four countries showed both similarities and differences in the levels of the appearance variables. Girls from India and Iran reported the highest levels of appearance satisfaction followed by those from China and Australia, whereas Iranian girls experienced the highest perceived discrepancies between their actual and ideal facial and bodily features. Notably, girls in China and India exhibited a greater value for their facial attributes than their bodily features. Key findings from this research are discussed below.

Relationships Between Actual-Ideal Discrepancies and Appearance Satisfaction

The results suggest that higher perceived facial discrepancies were only significantly negatively associated with lower appearance satisfaction for girls living in Iran, whereas higher perceived bodily discrepancies were only significantly negatively linked to lower appearance satisfaction for girls living in Australia. These patterns for Iran and Australia are consistent with self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987) and past studies that have found actual-ideal discrepancies on bodily attributes to correlate negatively with measures of body image (Alipoor et al., 2009; Jacobi & Cash, 1994; Kowner, 2004; Williamson et al., 1993). While these findings highlight how perceptions of discrepancies pertaining to different body features may be relevant to a girl’s sense of overall appearance, differential trends with respect to facial and bodily features within Iran and Australia may be stemming from their unique cultural contexts. For example, for Iranian girls wearing a hijab and loose-fitting clothes in public may provide more opportunities to engage in facial comparisons (Rastmanesh et al., 2009; Talk, 2022), whereas bodily comparisons may be more salient among Australians who are routinely exposed to the beach and the outdoor culture that emphasizes and greatly values the ideal bodily shape for girls and women (Field et al., 2019; Small, 2017). However, further longitudinal research is needed to determine the direction of these relationships.

Why this effect was not significant for China and India is somewhat counterintuitive, given the prevalence of body image concerns in these countries (e.g., Mellor et al., 2013; Nagar and Virk, 2017). These results only partially support the tenets of the self-discrepancy theory. While the reason for this cross-cultural variability is hard to determine, the body image literature acknowledges the complex interplay of cultural, social, psychological, and biological factors that shape body image attitudes among individuals (Rodgers et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 1999). It is possible that factors beyond perceived actual-ideal discrepancies may contribute to body image concerns in these countries. For instance, both China and India have distinct cultural beauty ideals and a strong influence of local celebrities that may shape body image perception of young girls (Ahuja & Pundir, 2022; Jackson et al., 2020; Jung, 2018; Nagar & Virk, 2017). Further research is needed to assess the extent to which different factors contribute to body image concerns in these countries, and how they may differ from the experiences in Australia and Iran.

Another unanticipated result was the lack of a significant interaction between actual-ideal discrepancies and the importance of attributes for either facial or bodily attributes. Nor was this interaction further moderated by country of residence. It is possible that controlling for other variables in the moderated moderation model may have suppressed these effects (MacKinnon et al., 2000) Given that body image is multiply determined, a range of other factors may be contributing to appearance concerns (Bovet, 2018; Rodgers et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 1999). For example, as suggested by sociocultural theory of body image, factors other than the ones examined in this study (e.g., sociocultural influences like family, peers, media) may hold the potential to contribute and better account for appearance concerns among young girls in all countries (Thompson et al., 1999).

Importance of Facial Attributes in Different Countries

The most interesting patterns of findings to emerge from the study were how different appearance variables were endorsed cross-culturally. The results showed that girls living in China and India placed higher importance on facial features than their bodily attributes, whereas girls in Australia and Iran considered their facial and bodily attributes as equally important to their sense of overall appearance. Trends from China and India broadly support the notion that people in some East Asian cultures place more value on their facial attributes rather than on the body and also appear to be consistent with representations of female beauty within Asian media that are more focused on facial attributes than the body (Jackson & Chen, 2008; Samizadeh, 2022; Samizadeh & Wu, 2018; Xu et al., 2010; Yip et al., 2019). These findings are not entirely surprising since facial beauty among many Asian cultures is an important marker of social worth and cultural capital and may be rooted in gendered norms that consider certain aspects of feminine beauty (e.g., lighter skin), key to their career or marital prospects (Bourdieu, 1984; Johri, 2011; Nagar, 2018; Samizadeh and Wu, 2018; Shroff et al., 2017). This may explain why girls in some cultures (e.g., China, India), heavily invest in facial beautification and enhancement like skin whitening, eyelid surgeries, etc. (Chen et al., 2017; Dash, 2021; Li et al., 2008; Samizadeh & Wu, 2018; Shroff et al., 2017; Statista, 2022a; Zhang, 2022).

Facial beautification practices (e.g., rhinoplasty or nose job) are also widely prevalent in Iran and have frequently been associated with wearing the hijab, which directs attention to facial attributes (Rastmanesh et al., 2009; Zojaji et al., 2018). Given this background, the finding that Iranian adolescents perceived their facial and bodily features to be equally important to their overall sense of appearance is somewhat unexpected, especially since girls in Isfahan also adhere to these clothing and head veiling customs, that emphasize their facial attributes. However, one potential explanation could be the wide variety of colours, designs, and styles in which the hijab, and manteau (long body coverings) are worn by Iranian girls and women (Talk, 2022), which may potentially expose body shape and could explain why Iranian adolescents place equal importance on their facial and bodily features. Furthermore, the study revealed that relative to girls in the other three countries, Iranian girls rated importance of facial and bodily attributes to be least important to their appearance. This finding could be attributed to their Islamic centred upbringing that encourages girls to de-emphasize appearance and instead focus on their faith, spirituality, and behavioral qualities (Ahmad et al., 1994; Mussap, 2009; Philips, 2012; Rafighdust, 2008). Nonetheless, further research is necessary to explore the factors driving these preferences among teenagers, especially cross-culturally.

Appearance Satisfaction and Perceived Discrepancies in Physical Attributes Across Cultures

With regards to overall body image, we found Australian adolescents were least satisfied with their overall appearance followed by girls in China, and then adolescents in India and Iran. One reason for this may be that appearance-based concerns are more pronounced in economically developed, individualistic societies where people typically follow a Western lifestyle, that emphasizes appearance and where social pressures to attain the beauty ideal may be higher (Hofstede, 2018; Holmqvist & Frisen, 2010). As noted earlier, the popularity of the beach and bikini body subculture in Australia may draw more attention to certain aspects of appearance, such as body shape or size, which may lead young girls to grow up in a more body-focused environment that may impact their body image (Field et al., 2019; Small, 2017). However, it should be noted that these contextual factors may not be applicable to all Western societies, especially those with colder climates (e.g., United Kingdom), and may be more relevant to girls from coastal regions of Sydney and Lismore, who experience this lifestyle firsthand. This cultural context within Australia sits in contrast to girls living in countries like China, India, and Iran who are exposed to the Western culture mainly through media.

It is also worth noting that Chinese girls reported being less satisfied with their appearance than girls from India and Iran. China’s economy is one of the largest in the world and ranks much higher than that of India and Iran (World Population Review, 2022b). Chinese girls from Fuzhou belong to one of the richest provinces in China, and are likely more affluent than Indian girls in New Delhi or Iranian girls from Isfahan, raising possibilities regarding the role of socioeconomic factors in body image (Swami, 2021). There may be, however, other possible explanations driving these trends that could surface through a more detailed investigation of these different sociocultural contexts.

Although evidence regarding which cultural group is more dissatisfied has been mixed, our study broadly supports the work of authors who found that Asian participants are generally more satisfied with their appearance than their Western counterparts (Akiba, 1998; Chen & Swalm, 1998; Mellor et al., 2013; Wardle et al., 2006). As argued earlier, it should be noted that Asia is not a homogeneous group (Bhopal et al., 1991; United Nations, 2019) and body image trends don’t always show the same pattern or results across studies, even in cultural contexts with seemingly similar backgrounds. Therefore, future research might benefit from focusing more on the nuances of a specific population than categorizing them in ways that could be reductionist and potentially obscure their uniqueness.

Similarities and differences were also observed in how perceived facial and bodily discrepancies were endorsed between the four countries. Although Australian girls reported the least discrepancy between their actual and ideal physical attributes, they did not differ from girls in India with respect to facial discrepancy, and also reported similar levels of bodily discrepancy as their Chinese counterparts. These findings stand in contrast to the suggestion that East Asians girls may be relatively less concerned about their bodily attributes than their counterparts in Western contexts (Chen & Swalm, 1998). Moreover, girls within all three countries reported experiencing greater discrepancies pertaining to their bodily attributes than their facial attributes. These similarities are consistent with previous cross-cultural studies that have found no differences in how different body image constructs are endorsed among girls from diverse cultural contexts (Gupta et al., 2001; Rubin et al., 2008) and may reflect ongoing cultural change that exposes young girls to similar globalised body size, shape and weight ideals (Knapp & Krall, 2021; Nasser, 1988a, b; Nasser et al., 2003; Swami, 2021). However, future research is needed to better understand what contributes to perceptions of facial and bodily discrepancies to improve our understanding of how these attitudes are cultivated cross-culturally.

Interestingly, comparisons of mean data indicated that girls in Iran may be dissimilar to girls from the other three countries. Despite reporting considerable satisfaction with their appearance, Iranian girls reported the greatest discrepancies for both facial and bodily attributes, but also placed the least importance on these attributes. While there may be several explanations for these findings, the most compelling one is the religious context of Islam, relevant to girls living in Isfahan, that encourages modesty, body acceptance, and less emphasis on external appearance (Ahmad et al., 1994; Philips, 2012; Rafighdust, 2008). Generally, these attitudes reported by Iranian adolescents are similar to previous studies showing that Muslim girls who wear a hijab tend to have a more positive body image and place less importance on appearance than girls who do not wear a hijab and non-Muslim girls (Durovic et al., 2016; Swami et al., 2013, 2014; Tolaymat & Moradi, 2011). This is not to suggest that Iranian adolescents are insulated against appearance related concerns. In fact, it has been noted that even when growing up in a historically conservative and religiously oriented cultural setting, young girls may be exposed to both traditional and foreign (e.g., Western) beauty norms (for a review of body image concerns in Iran see Shoraka et al., 2019). These ideals may be radically different from their own features, which may partly explain why these girls reported the highest discrepancies on bodily features. Further research on how Iran’s unique religious context contributes to the body image of young girls is necessary to support these interpretations, especially in a cross-cultural context.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

A number of limitations need to be noted regarding the present study. One source of uncertainty arises from the use of multilingual measures in this study that remain to be validated. Another limitation of this study pertains to the low-reliability scores observed for the facial discrepancy subscale in certain countries and the measure of appearance satisfaction in China (omega <. 70), raising concerns about the interpretation of the data (Cortina, 1993; Dunn et al., 2014). The cross-cultural and multilingual nature of this research poses certain measurement constraints since non-English and English versions of the measures used remain to be validated within the study sites. Future research could continue to remedy this by developing/adapting and validating measures within diverse cultural contexts. We also cannot exclude the possibility that there are a plethora of other factors that could better account for the relationship between perceived actual-ideal discrepancies and appearance satisfaction. A potentially fruitful avenue for future cross-cultural research may be to examine the role of perceived attainability of one’s facial and bodily ideals in this relationship, given the popularity of beautification practices, globally (ISAPS, 2020).

These findings are also further limited by the cross-sectional design of this study, in which the directionality of this relationship cannot be ascertained. It is possible that girls who feel less satisfied with their appearance might perceive greater discrepancies in their facial or bodily attributes. Further, the present study used a measure examining overall appearance satisfaction instead of separately assessing facial and bodily dissatisfaction. Future research could consider using a more targeted measure of appearance dissatisfaction to examine if perceived discrepancies in different physical attributes relate to appearance satisfaction for those particular attributes (e.g., facial discrepancies predicting facial dissatisfaction).

Even though one of the major strengths of this study lies in its use of an international sample of adolescent girls, findings from this study may only be applicable to specific sub-populations within these diverse countries (e.g., urban settings in all cultures). It is likely that individuals within a country may feel differently about their appearance, based on their cultural setting, economic wealth, degree of modernization and Westernization, and their own religious affiliation or the degree to which they adopt Western values. However, the nuance within different cultures may not have been fully captured. Future research could explore in more depth the contextual factors that may influence body image attitudes by including samples that are more representative of the entire population, thus minimizing potential biases. Finally, our sample only comprised of adolescent girls, and findings may not be transferable to other genders or different age groups.

Practice Implications

Findings from the present study have important implications for developing culturally sensitive intervention programs aimed at improving body image among adolescent girls from the four countries included in this research. While preventative efforts have primarily focused on weight and size-based attributes, such as disordered eating (for a review see Stice et al., 2021), this study highlights that girls within some cultural contexts (e.g., China and India) may value their facial attributes more than their bodily features. A greater focus on facial attributes may increase the likelihood of developing concerns with facial, hair, and skin-based attributes (Frederick et al., 2016; Frederick, Reynolds, Frederick et al., 2022a, b), which may be more relevant to conditions like facial dysmorphia rather than eating disorders (Vashi, 2016). Although most intervention programs are designed to improve body image more broadly (for a review on body image interventions see Alleva et al., 2015), future intervention and preventative measures could be improved by incorporating facial components, especially in cultures where such attributes hold greater importance.

Moreover, our research emphasizes the need to recognize and address the intersectionality of cultural nuances, gendered expectations, and socialization practices in shaping appearance-related experiences, given the pressure on girls to conform to appearance-based stereotypes. By considering these complex factors, interventions can be tailored to meet the specific needs and experiences of girls from diverse cultural backgrounds. Finally, this study expands our understanding of appearance-related experiences across diverse cultural contexts that have been underrepresented in the body image research literature.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings contribute to the nascent area of cross-cultural research on body image, examining the role of facial and bodily attributes. This study represents the first cross-cultural investigation to empirically examine the importance of facial and bodily attributes in adolescent girls, revealing that some cultures, such as China and India, place greater emphasis on facial attributes than bodily features. The results partially substantiate the applicability of self-discrepancy theory linking higher perceived actual-ideal discrepancies to lower appearance satisfaction for both facial and bodily attributes. However, our findings also highlight the cross-cultural variability of these relationships, indicating that perceived discrepancies may not always be relevant to appearance satisfaction, as originally proposed by this theory. Overall, these findings have important implications for identifying sub-groups that may require more attention with regards to body image interventions than others. To promote the well-being of all adolescent girls, it is imperative that future research identifies potential determinants of appearance concerns that account for the distinct social and gendered pressures experienced by girls in different cultural contexts.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the fact that participants have not consented to data release.

References

Ahmad, S., Waller, G., & Verduyn, C. (1994). Eating attitudes among asian schoolgirls: The role of perceived parental control. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 15(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(199401)15:1>91::aid-eat2260150111<3.0.co;2-7

Ahmadi, S., Heyrani, A., & Yoosefy, B. (2018). Prevalence of body shape dissatisfaction and body weight dissatisfaction between female and male students. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 18(4), 2264–2271. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2018.04341

Ahuja, K. K., & Pundir, T. (2022). Dreamgirls in tinseltown: Spotlighting body image stereotypes and sexism in popular indian media. Journal of Psychosexual Health, 4(2), 76–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/26318318221091019

Akiba, D. (1998). Cultural variations in body esteem: How young adults in Iran and the United States views their own appearances. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(4), 539. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224549809600409

Alipoor, S., Goodarzi, A., Nezhad, M., & Zaheri, L. (2009). Analysis of the relationship between physical self-concept and body image dissatisfaction in female students. Journal of Social Sciences, 5(1), 60–66. https://thescipub.com/abstract/jssp.2009.60.66

Alleva, J. M., Sheeran, P., Webb, T. L., Martijn, C., & Miles, E. (2015). A meta-analytic review of stand-alone interventions to improve body image. PLoS One, 10(9), e0139177. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139177

Aryan, S., Aryan, H., & Halderman, J. A. (2013). Internet censorship in Iran: A first look.https://www.usenix.org/conference/foci13/workshop-program/presentation/aryan

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021a). Cultural diversity Census. Australian Government. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/cultural-diversity-census/latest-release

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021b). Proficiency in spoken English (ENGLP). Australian Government. https://www.abs.gov.au/census/guide-census-data/census-dictionary/2021/variables-topic/cultural-diversity/proficiency-spoken-english-englp

Babakhani, A. (2022). Control over Muslim Women’s Bodies: A critical review. Sociological Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12529

Bakhshi, S. (2011). Women’s body image and the role of culture: A review of the literature. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 7(2), 374–394. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v7i2.135

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x

Bhopal, R. S. (2004). Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: For reflection and debate. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58(6), 441–445. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.013466

Bhopal, R., & Donaldson, L. (1998). White, European, Western, caucasian, or what? Inappropriate labeling in research on race, ethnicity, and health. American Journal of Public Health, 88(9), 1303–1307. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.88.9.1303

Bhopal, R. S., Phillimore, P., & Kohli, H. S. (1991). Inappropriate use of the term ‘Asian’: An obstacle to ethnicity and health research. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 13(4), 244–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042639

Bornioli, A., Lewis-Smith, H., Smith, A., Slater, A., & Bray, I. (2019). Adolescent body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Predictors of later risky health behaviours. Social Science Medicine, 238, 112458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112458

Bornioli, A., Lewis-Smith, H., Slater, A., & Bray, I. (2020). Body dissatisfaction predicts the onset of depression among adolescent females and males: A prospective study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 75(4), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-213033

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Harvard University Press. R. Nice.

Bovet, J. (2018). The evolution of feminine beauty. In Z. Kapoula, E. Volle, J. Renoult, & M. Andreatta (Eds.), Exploring transdisciplinarity in art and sciences (pp. 327–357). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76054-4_17

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Brockhoff, M., Mussap, A. J., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Mellor, D., Skouteris, H., McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2016). Cultural differences in body dissatisfaction: Japanese adolescents compared with adolescents from China, Malaysia, Australia, Tonga, and Fiji. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 19(4), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12150

Carey, R. N., Donaghue, N., & Broderick, P. (2011). What you look like is such a big factor’: Girls’ own reflections about the appearance culture in an all-girls’ school. Feminism & Psychology, 21(3), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353510369893

Cash, T. F., & Pruzinsky, T. E. (1990). Body images: Development, deviance, and change. Guilford Press.

Cash, T. F., & Szymanski, M. L. (1995). The development and validation of the Body-Image Ideals Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64(3), 466–477. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6403_6

Cattell, R. B. (1966). The Scree Test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(2), 245–276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

Chan, J., & Hurst, M. (2022). South asian women in the United Kingdom: The role of skin colour dissatisfaction in acculturation experiences and body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 42, 413–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.07.007

Chen, W., & Swalm, R. L. (1998). Chinese and american college students’ body-image: Perceived body shape and body affect. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 87(2), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1998.87.2.395

Chen, H. Y., Yarnal, C., Chick, G., & Jablonski, N. (2017). Egg white or sun-kissed: A cross-cultural exploration of skin color and women’s leisure behavior. Sex Roles, 78(3–4), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0785-4

Chen, T., Lian, K., Lorenzana, D., Shahzad, N., & Wong, R. (2020). Occidentalisation of beauty standards: Eurocentrism in Asia. International Socioeconomics Laboratory, 1(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4325856

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

Cunningham, M. R., Roberts, A. R., Barbee, A. P., Druen, P. B., & Wu, C. H. (1995). Their ideas of beauty are, on the whole, the same as ours”: Consistency and variability in the cross-cultural perception of female physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(2), 261–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.2.261

Dash, D. (2021). The impact of skin-lightening methods among individuals of Indian descent: A rapid review. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/mphcapstone_presentation/401/

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

Durovic, D., Tiosavljevic, M., & Sabanovic, H. (2016). Readiness to accept Western standard of beauty and body satisfaction among Muslim girls with and without hijab. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(5), 413–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12315

Fan, Z. T., Yu, X. Y., Yu, C. R., Liang, R., & Wang, K. (2020). Weight control behaviors and their association with real and perceived weight status among 1026 first year high school students in Lanzhou. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care, 28(9), 1051. https://doi.org/10.11852/zgetbjzz2019-1708

Field, C., Pavlidis, A., & Pini, B. (2019). Beach body work: Australian women’s experiences. Gender Place & Culture, 26(3), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2018.1541869

Frederick, D. A., Kelly, M. C., Latner, J. D., Sandhu, G., & Tsong, Y. (2016). Body image and face image in Asian American and White women: Examining associations with surveillance, construal of self, perfectionism, and sociocultural pressures. Body Image, 16, 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.12.002

Frederick, D. A., Pila, E., Malcarne, V. L., Compte, E. J., Nagata, J. M., Best, C. R., Cook-Cottone, C. P., Brown, T. A., Convertino, L., & Crerand, C. E. (2022a). Demographic predictors of objectification theory and tripartite influence model constructs: The US Body Project I. Body Image, 40, 182–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.012.

Frederick, D. A., Reynolds, T. A., Barrera, C. A., & Murray, S. B. (2022b). Demographic and sociocultural predictors of face image satisfaction: The US Body Project I. Body Image, 41, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022b.01.016.

Fu, X., & Wang, Y. (2015). Confucius on the relationship of beauty and goodness. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 49(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.5406/jaesteduc.49.1.0068

Garrusi, B., & Baneshi, M. R. (2017). Body dissatisfaction among Iranian youth and adults. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 33(9), e00024516. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00024516

Gattario, K. H., & Frisen, A. (2019). From negative to positive body image: Men’s and women’s journeys from early adolescence to emerging adulthood. Body Image, 28, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.12.002

Gramaglia, C., Delicato, C., & Zeppegno, P. (2018). Body image, eating, and weight. Some cultural differences. In M. Cuzzolaro & S. Fassino (Eds.), Body image, eating, and weight (pp. 427–439). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90817-5_31

Grogan, S. (2021). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women, and children (4 ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003100041

Gupta, M. A., Chaturvedi, S. K., Chandarana, P. C., & Johnson, A. M. (2001). Weight-related body image concerns among 18-24-year-old women in Canada and India: An empirical comparative study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 50(4), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00221-x

Gustafsson, B. A., Hasmath, R., & Ding, S. (2020). Ethnicity and inequality in China: An introduction. In Ethnicity and Inequality in China (1st ed., pp. 1–24). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Ethnicity-and-Inequality-in-China/Gustafsson-Hasmath-Ding/p/book/9780367534868

Halliwell, E., & Dittmar, H. (2006). Associations between appearance-related self-discrepancies and young women’s and men’s affect, body satisfaction, and emotional eating: A comparison of fixed-item and participant-generated self-discrepancies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(4), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205284005

Harcet, M. (2008). Qur’an dress code as the basis of egalitarianism in Islam. Ethnological Researches, 12(1), 191–211. https://hrcak.srce.hr/clanak/58139

Harkness, G. (2019). Hijab micropractices: The strategic and situational use of clothing by qatari women. Sociological Forum, 34(1), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12481

Harper, K., & Choma, B. L. (2019). Internalised White ideal, skin tone surveillance, and hair surveillance predict skin and hair dissatisfaction and skin bleaching among african american and indian women. Sex Roles, 80(11), 735–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0966-9

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use omega rather than cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But… Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Higgins, E. T. (1989). Self-discrepancy theory: What patterns of self-beliefs cause people to suffer? Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 93–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60306-8

Higgins, E. T. (1999). When do self-discrepancies have specific relations to emotions? The second-generation question of Tangney, Niedenthal, Covert, and Barlow (1998). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(1313–1317). https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1313

Higgins, E. T., Klein, R., & Strauman, T. (1985). Self-concept discrepancy theory: A psychological model for distinguishing among different aspects of depression and anxiety. Social Cognition, 3(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1985.3.1.51

Hofstede, G. (2018). The 6-D Model – Countries comparison.https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/australia,china,india,iran/

Holmqvist, K., & Frisen, A. (2010). Body dissatisfaction across cultures: Findings and research problems. European Eating Disorders Review, 18(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.965

IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 [Computer software]. IBM Corporation.

International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS; 2020). ISAPS Global Survey Results.https://www.isaps.org/medical-professionals/isaps-global-statistics/

Ip, H. Y. (2003). Fashioning appearances: Feminine beauty in chinese communist revolutionary culture. Modern China, 29(3), 329–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700403029003003

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2008). Sociocultural predictors of physical appearance concerns among adolescent girls and young women from China. Sex Roles, 58(5), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9342-x

Jackson, T., Cai, L., & Chen, H. (2020). Asian versus Western appearance media influences and changes in body image concerns of young Chinese women: A 12-month prospective study. Body Image, 33, 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.03.008

Jacobi, L., & Cash, T. F. (1994). In pursuit of the perfect appearance: Discrepancies among self-ideal percepts of multiple physical attributes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24(5), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00588.x

Jaeger, B., Ruggiero, G. M., Edlund, B., Gomez-Perretta, C., Lang, F., Mohammadkhani, P., Sahleen-Veasey, C., Schomer, H., & Lamprecht, F. (2002). Body dissatisfaction and its interrelations with other risk factors for bulimia nervosa in 12 countries. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 71(1), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1159/000049344

Johri, R. (2011). Mothering daughters and the fair and lovely path to success. Advertising & Society Review, 12(2), https://doi.org/10.1353/asr.2011.0014

Jones, D. C. (2001). Social comparison and body image: Attractiveness comparisons to models and peers among adolescent girls and boys. Sex Roles, 45(9/10), 645–664. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014815725852

Jung, J. (2018). Young women’s perceptions of traditional and contemporary female beauty ideals in China. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 47(1), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12273

Kagitcibasi, C. (1996). The autonomous-relational self: A new synthesis. European Psychologist, 1, 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.1.3.180

Kagitcibasi, C. (2017). Family, self, and human development across cultures.https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315205281

Kling, J., Kwakkenbos, L., Diedrichs, P. C., Rumsey, N., Frisen, A., Brandao, M. P., Silva, A. G., Dooley, B., Rodgers, R. F., & Fitzgerald, A. (2019). Systematic review of body image measures. Body Image, 30, 170–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.06.006

Knapp, G., & Krall, H. (2021). Youth cultures, lifeworlds and globalisation—An introduction. In Youth cultures in a globalized world (pp. 1–10). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65177-0_1

Kowner, R. (2004). When ideals are too “far off”: physical self-ideal discrepancy and body dissatisfaction in Japan. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 130(4), 333–364. https://doi.org/10.3200/MONO.130.4.333-364

Koyfman, S. (2018). Which countries speak the least English? Babbel. https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/which-countries-speak-the-least-english

Levy, R. (2012). The Persian language (RLE Iran B) (1st ed.). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-Persian-Language-RLE-Iran-B/Levy/p/book/9780415608558

Li, C. N., & Thompson, S. A. (1989). Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar (Vol. 3). University of California Press. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520066106/mandarin-chinese

Li, E. P., Min, H. J., & Belk, R. W. (2008). Skin lightening and beauty in four Asian cultures. Advances in Consumer Research, 35, 444–449. http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/13415/volumes/v35/NA-35

Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722