Abstract

We examined whether gay men (Studies 1–2) and lesbian women (Study 1) who harbor internalized stigma due to their sexuality will desire a romantic relationship that reflects conventional, complementary gender roles where one partner is stereotypically feminine and the other is stereotypically masculine, in terms of both personality traits and division of household labor. Results showed that, among gay men with high (but not low) internalized stigma, self-ascribed masculinity was positively related to preferences for an ideal partner with stereotypically feminine traits. Preferences for partners with gender complementary traits did not emerge among women, or among men high in self-ascribed femininity. Contrary to predictions, internalized stigma was not associated with preferences for a gender-complementary division of household chores. Instead, internalized stigma was associated with the avoidance of tasks that are stereotypically gender incongruent—women high (vs. low) in stigma preferred for the partner (vs. self) to do so-called masculine (but not feminine) chores, whereas men high (vs. low) in stigma preferred for the partner (vs. self) to do stereotypically feminine (but not masculine) chores. Study 2 also included an experimental manipulation to test whether these effects were influenced by societal exclusion or acceptance, but there was no evidence of this.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Heteronormativity is an ideology that promotes a specific brand of heterosexuality—monogamous relationships between men and women who adhere to strict gender roles—as necessary and normal (Ingraham, 2006; Jackson, 2006; van der Toorn et al., 2020; Warner, 1991). The concept stems from second-wave feminists, who argued that heterosexuality is not natural or inevitable, but a highly organized social institution—in essence, a normalized and “compulsory” power arrangement (Rich, 1980; Rubin, 1975, 1984/1993). Men and women are socialized to “do gender”—that is, act in ways that are stereotypically masculine or feminine—which serves to perpetuate a gendered division of labor (Butler, 1990; West & Zimmerman, 1987). Thus, people’s personal attitudes, behaviors, and self-concepts are a reflection of the political status quo (i.e., the personal is political; Hanisch, 1969; see also Mills, 1959). This proposition has been at the heart of, and empirically supported by, myriad lines of social psychological research demonstrating that gender norms regulate the behavior of heterosexual men and women (e.g., Bem & Lenney, 1976; Dahl et al., 2015; Deaux & Major, 1987; LaFrance & Banaji, 1992; Prentice & Carranza, 2002; Vandello & Bosson, 2013) in ways that maintain and bolster the gender hierarchy (Eagly & Steffen, 1984; Glick & Fiske, 2001; Heilman, 2001; Morgenroth & Ryan, 2021; Napier et al., 2010; Rudman & Phelan, 2008; Vescio & Kosakowska-Berezecka, 2020).

The question of how heteronormativity manifests in the relationships of those outside its boundaries—for instance, gay men and lesbian women—has been pondered by feminist and queer theorists (Butler, 1990; Rubin, 1984/1993; Schilt & Westbrook, 2009; Warner, 1991), but there is far less quantitative work in this domain. Both scholars and activists have noted an “assimilationist/activist” split, with the former group seemingly willing to adapt to (vs. challenge) heteronormative subjectivity (Kitzinger & Wilkinson, 1994; Shepard, 2001; Warner, 1991). In our research, we seek to shed light on this split—namely, to understand whether lesbian women and gay men sometimes embrace heteronormative customs, and if so, why. According to psychological theories, assimilationist (or “system-supporting”) behavior among members of a subordinate group is generally a reflection of internalized inequality, such as outgroup favoritism (Jost, 2020) and internal self-loathing (Allport, 1979; Cass, 1979). Based on this idea, we investigate one potential construct that might be related to the adoption (vs. rejection) of heteronormative dynamics in same-gender relationships—namely, internalized sexual stigma. In two studies, we examine whether lesbian women (Study 1) and gay men (Studies 1–2) who harbor shame about their sexual orientation are more likely to aspire to heteronormative ideals—specifically, complementary gender roles—in their same-gender relationships.

Similarity, Complementarity, and Division of Labor in Same-Gender Relationships

The idea that same-gender couples will emulate the (stereotypically gendered) dynamics of a heterosexual relationship appears to thrive in the public imagination (e.g., Henry & Steiger, 2022; Solomon, 2015). For example, research has shown that same-gender couples on television shows are typically portrayed in a gendered way (with one member as dominant, and the other submissive), as are heterosexual couples (Holz Ivory et al., 2009). In another study, heterosexual participants who read vignettes describing same-gender couples with varying gender expressions disproportionately assigned the kinds of household chores that are considered stereotypically feminine (e.g., cooking, cleaning) to the feminine-typed partner, and chores considered stereotypically masculine (e.g., auto maintenance; lawn work) to the masculine-typed partner (Doan & Quadlin, 2019). This is likely the result of a general proclivity for people to perceive sexual orientation as a fundamentally gendered phenomenon, and through a heteronormative lens (Henry & Steiger, 2022).

Investigations of dynamics in actual same-gender relationships, however, indicate that gender complementarity among gay and lesbian couples is not the norm. Specifically, research shows that same-gender couples tend to establish much more egalitarian patterns of responsibilities and decision-making than their heterosexual counterparts (Goldberg et al., 2012; Kurdek, 2006; Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007; Peplau & Ghavami, 2009; Solomon et al., 2005). This appears to be especially true among lesbian women (van der Vleuten et al., 2020; see also Brewster, 2017; Dunne, 1997). Further, unlike heterosexual couples for whom power disparities are the norm (e.g., Sprecher & Felmlee, 1997), most same-gender couples (especially lesbian women) explicitly reject imbalances of power in their relationships and eschew organization around so-called masculine and feminine roles (Dunne, 1997; Kurdek, 1995; Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007).

Research has also examined the personality dynamics in same-gender relationships (i.e., stereotypically feminine and masculine traits; e.g., Prentice & Carranza, 2002). Here, too, research suggests that gender complementarity is less common for same- (vs. other-) gender couples. Most same-gender couples express preferences for partners who are similar to themselves (Boyden et al., 1984; Phua, 2002), and it seems as though these preferences are often actualized. For instance, a recent meta-analysis found that male and female individuals in same-gender couples are more similar to their partners on stereotypic masculinity/femininity related traits (namely, agency and communion) than heterosexual couples (Hsu et al., 2021). Another series of studies found that gay men were no more similar (or different) to their partners than they were to randomly paired individuals in terms of masculinity/femininity (Bartova et al., 2017). In contrast, a study on women in committed same-gender relationships found that partners tend to complement each other in terms of dominance—i.e., be composed of one dominant and one submissive individual—but not in terms of warmth (Markey & Markey, 2013). However, this balancing of dominance and submission is similar to what is found in research on dyadic interactions more generally (e.g., between strangers or same-gender roommates), suggesting a general pattern that applies to a variety of interpersonal contexts (see Markey & Markey, 2013).

As a whole, the existing evidence suggests that same-gender couples, on average, may reject heteronormative dynamics, favoring egalitarian divisions of labor and similarity (rather than complementarity) in psychological attributes. However, there appears to be substantial variance in the extent to which same-gender couples reject (vs. attempt to emulate) heteronormative dynamics, and several scholars have suggested that this is likely related to how much individuals reject (vs. accept) the existing social hierarchy, which valorizes heterosexuality (Kitzinger & Wilkinson, 1994; Shepard, 2001; Warner, 1991). Thus, it could be the case that the desire to replicate traditional heteronormative pairings (i.e., gender complementarity) in same-gender relationships does occur among a subgroup of sexual minorities—namely, those who have internalized inferiority due to their sexual orientation.

The Role of Internalized Stigma and System Justification

Internalized stigma refers to "the gay person’s direction of negative social attitudes toward the self” (Meyer & Dean, 1998, p. 161; also referred to as sexual stigma; internalized homophobia, homonegativity or heterosexism; internalized oppression; and internalized inferiority; e.g., Herek et al., 1998; Jost et al., 2004; Shidlo, 1994). Studies from across the globe have found that internalized stigma is strongly and robustly linked to poorer mental and physical health in gay men and lesbian women (e.g., Berg et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2019; Liang & Huang, 2022; Meyer, 2003; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Suppes et al., 2019), which leads to relationship dissatisfaction (Nguyen & Pepping, 2022; Sommantico et al., 2020).

According to system justification theory (Jost, 2020; Jost & Banaji, 1994), internalized stigma about one’s sexuality—such as displays of outgroup favoritism and ingroup derogation found among members of other disadvantaged groups (Calogero, 2013; Jost & Banaji, 1994; Rudman et al., 2002; Rivera Pichardo et al., 2022)—is a byproduct of a conflict between a motivation to maintain a positive view of the system and one’s own low societal status within that system. More specifically, the theory posits that people are motivated (often unconsciously) to view the social systems in which they live and work as fair and legitimate, even when that system puts them at a disadvantage. Thus, members of both high and low status groups tend to engage system-justifying mechanisms that psychologically bolster the system’s legitimacy, even when doing so is antithetical to their group interest (e.g., Calogero & Jost, 2011; Jost et al., 2004; Kay & Jost, 2003; Napier et al., 2006, 2020).

Harboring stigma regarding one’s sexuality is associated with other system-supporting attitudes and behaviors among sexual minorities, which is in line with the idea that internalized stigma is a byproduct of a tendency to justify the system. For example, studies have shown that internalized stigma is associated with beliefs that support the status quo (e.g., system justification, political conservatism, and mainstream religiosity; Herek et al., 2009; Pacilli et al., 2011), and to the derogation of same-gender parenting among gay men (but not lesbian women, presumably because of heteronormative ideologies regarding differences in fitness for parenting between the genders; Pacilli et al., 2011). Another set of studies found that internalized stigma is related to support for traditional gender roles among gay men (Salvati et al., 2021). Specifically, gay men high (but not low) on stigma showed lower support for a gay (vs. heterosexual) leader, rated a masculine-typed gay male leader as more effective than a feminine one, and showed lower intention to apply for a leadership position when they were told they scored low (vs. high) on a masculinity test.

Another tenant of the heteronormative system is gender typicality, and, in line with this, those who are motivated to justify the system are more likely to act in gender-congruent ways (e.g., Jost & Kay, 2005; Kray et al., 2017; Lau et al., 2008). Thus, insofar as internalized stigma is an indicator of a motivation to justify the system, system justification theory would also predict that gay men and lesbian women who have internalized inferiority about their sexuality would be especially likely to exaggerate their gender typical traits (and minimize their gender incongruent ones). Virtually no studies have examined internalized stigma and gendered traits in lesbian women, but studies on gay men have repeatedly found an association between internalized stigma and masculinity ideals for the self, including conformity to masculinity norms (Thepsourinthone et al., 2020); preoccupations with appearing masculine (Hunt et al., 2020; Sánchez & Vilain, 2012); masculine body ideals (Kimmel & Mahalik, 2005); and self-labeling as “tops” (i.e., partners who predominately take the insertive role in anal sex; Hart et al., 2003; Zheng & Fu, 2021). Another study found that gay male participants subject to a masculinity threat (vs. affirmation) were more likely to distance themselves from feminine gay men, and reported being more similar to masculine gay men (Hunt et al., 2016).

Taken together, it appears that the acceptance and internalization of societal inferiority underlies people’s attempts to conform to a heteronormative status quo (e.g., Allport, 1979; Cass, 1979; Warner, 1991), at least for gay men in terms of self-presentation, attitudes and beliefs. In the current work, we examine whether this extends to romantic relationships.

Gender Complementarity in Same-Gender Romantic Relationships

In this work, we focus on the ideal relationship pairings of gay men and lesbian women to examine whether sexual minorities who harbor stigma about their sexual orientation will attempt to compensate by seeking same-gender relationships that embody heteronormative ideals—specifically, complementary gender roles and personality traits. Although same-gender relationships, by definition, violate heteronormative standards in terms of gender pairing (i.e., man and woman), we propose that internalized stigma will be associated with a preference for relationships that otherwise reflect the heteronormative status quo, where one partner is more stereotypically masculine and the other more stereotypically feminine.

A few studies have examined the desirability of gendered traits in same-gender coupling by examining the content of dating profiles (e.g., Bailey et al., 1997; Gonzales & Meyers, 1993; Phua, 2002). This research has shown that masculinity is particularly valued for both the self and potential partners among gay men (Bailey et al., 1997; Gonzales & Meyers, 1993), whereas lesbian women tended to describe themselves and their preferred partners androgynously (i.e., having both masculine and feminine traits; Bailey et al., 1997). However, these studies did not include measures of internalized stigma. Further, the content of dating profiles, especially those from the 1990’s (printed in newspapers!), may not be reflective of the general population.

Research on intercourse position preferences among gay men in China offers indirect, but compelling, support for the proposition that internalized stigma is associated with gender complementarity in same-gender relationships. Specifically, there is strong evidence that intercourse position preference is correlated with gendered traits and interests, such that gay men who identify as tops scored higher than “bottoms” (those who prefer the receptive role in sexual intercourse) on masculinity and masculine-typed interests (Zheng et al., 2012, 2015), and were more likely to desire power during sex (Xu & Zheng, 2018). Those who identify as “versatiles” (i.e., willing to adopt either position) tended to score in between tops and bottoms on these variables. In addition, self-identified bottoms and versatiles preferred men with more masculine faces, bodies, and personality traits compared to tops (Zheng, 2021; Zheng & Zheng, 2016). Researchers from this lab have also assessed gay men’s belief that intercourse position preferences ought to be reflections of complementary gender roles (a construct they called “internalized traditional gender roles”), with items such as: “It is normal for bottoms and tops in romantic relationships to call each other ‘honey’ and ‘hubby’,” and “Tops should spend more on dating” (Zheng & Fu, 2021). Critical to our arguments, this belief that same-gender relationships ought to be gender complementary was more strongly endorsed among those high (vs. low) on internalized stigma, and among those with exclusive intercourse preferences (i.e., “exclusive tops” and “exclusive bottoms”) compared to versatile tops, versatile bottoms, and versatiles (Zheng & Fu, 2021). In another study, researchers found that hostile sexism (another system-justifying belief) influenced gay men’s partner choice, such that tops and bottoms who endorsed hostile sexism were more likely to require an exclusively complementary sexual partner (Zheng et al., 2017). Taken together, this research suggests that there is a connection between internalized stigma and preferences for sexual intercourse that emulates heterosexual pairings, at least among gay men.

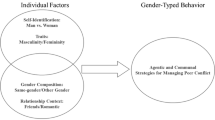

The aim of the current research is to examine whether internalized stigma manifests in a desire for gender complementary same-gender relationships more generally—in terms of personality traits and division of household labor. Our thesis is that gay men and lesbian women will generally prefer partners who are similar to them, and to have an egalitarian division of labor (as previous research has shown; e.g., Kurdek, 2006; Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007; Solomon et al., 2005), but this will be moderated by internalized stigma, such that gay men and lesbian women who harbor shame about their sexuality will rate their ideal relationship partner as one that “complements” them in terms of traditional gender roles. Thus, across two studies, we test the proposition that, among those who are high (vs. low) in internalized stigma, lesbian women (Study 1) and gay men (Studies 1–2) who self-describe in gender typical ways (i.e., masculine men and feminine women) will prefer gender incongruent partners, whereas those who self-describe as gender incongruent (feminine men and masculine women) will show a preference for gender typical partners.

There are, however, theoretical reasons to expect caveats to these predictions. First, it is possible that the preference for gender complementarity may be particularly strong among individuals who self-describe in more gender typical (vs. incongruent) ways. As we have reviewed, previous research has shown that internalized stigma is related to self-ascribed gender typicality (at least in men; e.g., Hunt et al., 2020). Insofar as system justifying motivations should, in theory, lead people to aim for gender typicality in the self, and gender complementarity in their relationships, it seems likely that gay men and lesbian women who self-describe in gender typical ways (and thus are presumably more inclined to justify a heteronormative system) may be more likely to exhibit preferences for gender complementary partners. In contrast, those who self-describe in gender incongruent ways may show less of a preference for complementarity. It also suggests that internalized stigma might affect the types of behaviors people are willing to engage in—namely, gay men with high internalized stigma might be reluctant to engage in stereotypically feminine activities, and lesbian women with high internalized stigma might be reluctant to engage in stereotypically masculine activities. We test this proposition in our studies, in terms of how stigma affects people’s willingness to take on (stereotypically feminine and masculine) household chores.

Second, although our “strong” prediction is that internalized stigma will be associated with a desire for gender complementary same-gender relationships more generally, there are reasons to suspect this will only be the case for men, and not women. Beyond its correlates with mental health, research on internalized stigma among lesbian women is stunningly scarce. Research does show, however, that women score much lower on internalized stigma compared to gay men (Herek et al., 1998; Sommantico et al., 2020), and have more androgynous self-concepts (Bailey et al., 1997) and a more egalitarian division of labor at home, compared to gay men and heterosexual people (Brewster, 2017; Dunne, 1997). Because they are especially marginalized even within the gay community, lesbian women (vs. gay men) might be particularly resistant to dominant (heteronormative) ideologies and more likely to embrace difference (Hooks, 1984). Another reason to suspect that internalized stigma will be less likely to manifest as gender complementary relationship preferences among women is based on research conducted with straight participants, which has found that system justifying motivations lead to the defense of heteronormative relationships among men, but not women (Day et al., 2011; see also Lau et al., 2008).

Overview of Studies

Across two studies, we test the proposition that internalized stigma among lesbian women (Study 1) and gay men (Studies 1–2) will be associated with attempts to emulate traditional gender roles in their same-gender relationships by expressing a stronger preference for gender complementary partners. In both studies, we measure people’s self-ascription of stereotypically masculine and feminine personality traits and their ideal division of household labor. Household tasks are historically gendered—e.g., cooking and cleaning are viewed as feminine tasks, whereas household repairs and yard work are masculine (see Goldberg, 2013 for a review). There has been considerable interest in, and several investigations of, the division of domestic labor in same-gender couples (e.g., Brewster, 2017; Carrington, 1999; Miller, 2018; Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007; van der Vleuten et al., 2020), but empirical examinations of what psychological factors might underlie people’s proclivities to take on different household roles are rare. This work serves to extend current knowledge about same-gender romantic relationships by examining the role of internalized stigma in the gendered dynamics of gay and lesbian couples.

In Study 1, we examine the associations between internalized stigma, the ascriptions of gendered traits to the self and the ideal partner, and preferences for the division of household chores in the ideal relationships of lesbian women and gay men. In addition to providing a test of our hypothesis, this study provides insight into the associations between stigma and self-ascribed masculinity and femininity in women, which is lacking in the current literature. In Study 2, we aim to replicate the findings from Study 1 in a different sample of gay men, and to extend them by testing whether this process is affected by perceptions of societal exclusion or inclusion. Specifically, we predict that gay men high on internalized stigma will show preferences for gender complementary relationships and gender typical tasks in a control condition, and that that this will be exacerbated when anti-gay discrimination is made salient (i.e., in a “threat” condition), but reduced or eliminated when participants are told of the increasing social acceptance of same-gender relationships (i.e., an “affirmation” condition).

Study 1

Method

Participants

We posted the study on Prolific, a British-based online survey platform, and it was made available to all users who identified themselves as “non-heterosexual” in Prolific’s pre-screening questionnaire in the USA and UK. No data were examined or analyzed until data collection was completed. We obtained responses from 354 individuals. To be able to separately analyze responses from self-identified men and women who are interested in same-gender relationships, we analyzed data only from 291 respondents who identified as”gay men” (n = 163) and “lesbian women” (n = 128). Participants excluded from analyses identified their gender as “non-binary” (n = 16) or “transgender” (n = 17), or their sexual orientation as “heterosexual” (n = 15), “bisexual” (n = 10), or “other” (n = 5).

Most participants (84.9%) reported their ethnicity as “White” (n = 247). The remainder of the sample identified as: Asian (n = 15); Hispanic/Latinx (n = 11); Black (n = 7); “Mixed/multiple” (n = 4); Middle Eastern (n = 4); or “other” (n = 3). The average age was 30.98 years (SD = 10.42; with ages ranging from 18 to 69 years old), and 52.6% (n = 153) of participants had a college degree or higher. Using a slider that ranged from 0 to 100, participants indicated their “social position relative to other people in your country” (M = 47.07, SD = 20.82). There were no differences between male and female respondents on age, t(289) = 0.79, p = .433, education, t(289) = 1.75, p = .083, or social position ratings, t(289) = 1.05, p = .296.

In terms of relationship status, 44.3% (n = 129) of the sample was single; 21.6% (n = 63) were living with their partner; 20.3% (n = 59) were in a non-cohabitating committed relationship; 11.7% (n = 34) were legally married, and the remaining participants were separated (n = 1), divorced (n = 3), or “other” (n = 2). Men were slightly more likely to report being single (47.2% or n = 77) compared to women (40.6% or n = 52). Men were also more likely to be in a cohabitating relationship (24.5% or n = 40) compared to women (18.0% or n = 23), whereas women were more likely to report being married (18.8% or n = 24) compared to men (6.1% or n = 10), χ2(6) = 13.90, p = .031.

Correlations between participants’ demographic characteristics and the focal study variables are provided in the supplementary materials (see Sect. 1 of the online supplement).

Procedure

Participants were presented with a list of traits and asked to rate the extent to which each trait was self-descriptive. They were then presented with items assessing their internalized sexual stigma. Following this, participants were asked to think about their ideal romantic relationship. To minimize any influence of people’s current relationship, we told participants: “You may already have a partner, and no matter how much you care about them, there might be things you wish were distributed differently in your relationship. Here, we ask that you imagine your absolute ideal romantic relationship.” They then rated their ideal partner on the same traits that they rated themselves at the onset of the study, and indicated their preferences for the division of household labor in their ideal romantic relationship. At the end of the study, they filled out a brief demographic questionnaire, and were thanked, debriefed, and compensated for their time.

This study was reviewed and approved by the first author’s institutional review board for compliance with standards of the ethical treatment of human participants.

Measures

For each scale, items were averaged, with higher numbers indicating higher scores for each construct.

Masculinity and Femininity Ratings of Self and Ideal Partner

Participants rated 20 traits, taken from studies on masculine and feminine stereotyping (i.e., Galinsky et al., 2013; Petsko & Bodenhausen, 2019), on how descriptive they were of themselves and their ideal partners, measured on a scale from 1 (definitely not) to 5 (definitely yes). As detailed in the supplementary materials (see Sect. 2 of the online supplement), factor analyses revealed a clear cluster of masculine traits (i.e., “aggressive” and “rough;” r(289) = .51, p < .001, for self-ratings and for partner ratings) and a clear cluster of feminine traits (i.e., “sensitive,” “gentle,” and “delicate;” α = .74 for self-ratings; α = .65 for partner ratings). We computed the means of these trait clusters to use as our measures of masculinity and femininity, respectively, for the self and the ideal partner (where higher scores indicate higher levels of masculinity or femininity).

Internalized Sexual Stigma

Participants responded to seven items assessing stigma about their sexual orientation (taken from Wagner, 2011; e.g., “If there were a pill to make me straight, I would take it;” α = .91), with responses recorded on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Division of Household Labor

We asked participants about their preference for doing various household tasks in their ideal romantic relationship. Participants rated their desired frequency of performing five stereotypically masculine tasks (i.e., paying for a date; taking out the trash; taking care of the lawn; driving the car when you are both going somewhere together; repairing things around the house) and four stereotypically feminine tasks (cooking meals; cleaning the house/apartment; doing the laundry; shopping for groceries) on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). We took the mean of these items to construct scores for self-preferences for masculine (α = .61) and feminine (α = .53) household tasks. Participants also rated how often their ideal partner would do the same tasks (1 = never; 5 = always). We computed the means to obtain measures of preferences for a partner who does masculine (α = .68) and feminine (α = .61) tasks.

Sensitivity analyses conducted with G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007) showed that for power (1 − β) of .80 and a significance level of .05, our sample sizes were sufficient for detecting the predicted interaction with a critical F(1, 157) = 3.90 in the male sample, and F(1, 122) = 3.92 in the female sample, for a linear regression model with five predictors.

Results

The means and standard deviations, comparison of means (i.e., t-tests) and bivariate correlations among the focal variables as a function of participant gender are listed in Table 1. As can be seen in the table, there were very few gender differences on the focal variables. The exceptions were that men (vs. women) reported slightly higher sexual stigma and stronger preferences for a partner with masculine traits.

Bivariate correlations indicate that most participants prefer partners with traits that are similar to their own—i.e., self-ascribed masculinity was positively correlated with wanting a partner with masculine traits, and self-ascribed femininity was positively correlated with wanting a partner with feminine traits, for both men and women. There was no evidence that, on average, participants preferred gender complementary partners: men and women’s self-ascribed masculinity was unrelated to their ideal partner’s femininity; self-ascribed femininity was unrelated to an ideal partner’s masculinity among women, and negatively related among men.

The correlations also indicate that stigma is negatively associated with participants’ own gender incongruent traits and tasks. Specifically, men’s sexual stigma was negatively related to self-ascribed femininity and to preference for feminine household chores, but unrelated to self-ascribed masculinity and preference for masculine household chores. Among women, sexual stigma was negatively related to self-ascribed masculinity and preference for masculine chores, but unrelated to femininity and preference for feminine chores.

Partner Traits

To test our hypothesis, we conducted multilevel linear regression models, separately for men and women, predicting the ideal partner’s traits, with trait type (masculine vs. feminine) as a within-subjects variable and self-ascribed masculinity and femininity (mean-centered), internalized stigma (mean-centered), and the interactions between masculinity and femininity with stigma, and all interactions with trait type, allowing for a random slope of trait type. In other words, ratings of ideals partners’ traits were nested within participants, and predicted with a dummy code indicating the type of trait (feminine = 0 and masculine = 1) along with the other focal variables.

Results showed a positive effect of trait type, such that people preferred partners with more feminine (vs. masculine) traits, for both men, b = -1.69, SE = .08, p < .001, and women, b = -2.28, SE = .09, p < .001. This was qualified by interactions with self-ascribed masculinity for men, b = .46, SE = .10, p < .001 (but not women, b = .20, SE = .13, p = .114), self-ascribed femininity for both men, b = -.58, SE = .10, p < .001, and women, b = -.58, SE = .13, p < .001, and 3-way interactions between trait type, masculinity, and stigma for both men, b = -.22, SE = .09, p = .015, and women, b = -.43, SE = .14, p = .003 (see Sect. 3 of the online supplement for the full model).

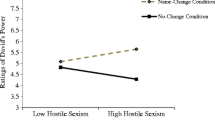

Table 2 shows the simple slopes for predicting feminine traits and masculine traits separately. As seen in the first sets of columns in Table 2, men’s self-ascribed femininity was positively associated with their preference for a partner’s feminine traits. Self-ascribed masculinity was unrelated to preference for a partner’s feminine traits, but the predicted masculinity-by-stigma interaction emerged (see Fig. 1). Simple slopes analyses showed that, among men high in stigma (+ 1 SD), self-ascribed masculinity is positively related to wanting a partner with feminine traits, b = .20, SE = .09, p = .035, whereas these constructs were unrelated among men low in stigma (-1 SD), b = -.08, SE = .09, p = .389. Looking at this interaction the other way, for men who rate themselves as low in masculinity (–1 SD), stigma is unrelated to a partner’s femininity, b = -.10, SE = .08, p = .169; for men high in masculinity (+ 1 SD), however, stigma is positively associated with wanting a partner with feminine traits, b = .14, SE = .06, p = .024.

For men’s preferences for partner’s masculine traits, only self-ascribed masculinity was significantly (and positively) related, and this was not moderated by internalized stigma.

Results for women’s partner preferences are shown in the last sets of columns of Table 2. As seen in that table, women’s self-ascribed femininity was positively associated with preferences for a partner’s feminine traits, and this was not moderated by internalized stigma. Women’s self-ascribed masculinity (but not femininity) was positively associated with their ideal partner’s masculine traits, and this was moderated by an unexpected masculinity-by-stigma interaction. Analyses of the simple slopes revealed that, among women low in stigma (-1 SD), self-ascribed masculinity was positively related to preference for a partner’s masculine traits, b = .66, SE = .08, p < .001, but this association was absent among women high in stigma, b = –.01, SE = .18, p = .959.

Estimate of Effect Size

Because it is difficult to obtain accurate estimates of accounted variance for multilevel models (Rights & Sterba, 2019), in order to test the size of the predicted interaction effect, we conducted a linear regression model predicting men’s ideal partner’s feminine traits with the five predictors (self-ascribed femininity and masculinity, internalized stigma, and their interactions). Results showed that the additional variance accounted for (i.e., F-change) by the masculinity-by-stigma interaction was F(1, 157) = 6.75, which is larger than the critical F(3.90) obtained in our sensitivity analysis.

Division of Household Labor

We next examined whether stigma led participants to show a preference for a traditional (gendered) division of household labor. We computed the difference between self- and partner ratings of feminine chores and masculine chores (i.e., self-preference minus partner preference, so that higher numbers indicate more self-preference, lower numbers indicate more partner preference, and zero indicates an equal division of labor).

We conducted multilevel models, separately for men and women, predicting this self- versus partner difference score with chore type (feminine = 0 and masculine = 1), internalized stigma (mean-centered) and the interaction between stigma and trait-type, allowing for a random slope of trait-type.

Results showed a significant main effect of chore type, such that self (vs. partner) preference for feminine chores is negatively related to self (vs. partner) preference for masculine chores, for both men, b = -.44, SE = .10, p < .001, and women, b = -.26, SE = .12, p = .034, suggesting a gendered division of labor. There was a negative main effect of stigma among men, b = -.14, SE = .06, p = .019 (but not among women, b = .06, SE = .09, p = .523), such that internalized stigma was inversely related to gay men’s preference to do feminine chores. The trait type-by-stigma interaction was significant for both men, b = .21, SE = .09, p = .026, and women, b = -.32, SE = .13, p = .020 (see Fig. 2).

Analysis of the simple slopes showed that men’s internalized stigma was negatively related to willingness for the self (vs. partner) to do feminine chores, b = -.14, SE = .06, p = .019, but unrelated to task differentiation for masculine chores, b = .07, SE = .07, p = .310. For women, the opposite pattern emerged, such that women’s internalized stigma was negatively related to a preference for the self (vs. partner) to do masculine chores, b = -.26, SE = .10, p = .014, but unrelated to their preferences for feminine chores, b = .06, SE = .09, p = .523.

Discussion

Data from this first study support our hypothesis that individuals with high internalized stigma about their sexual orientation would aim for gender complementarity (in terms of personality traits) in their romantic relationships, but only for men who self-describe as masculine. Specifically, among men with high internalized stigma, those high (but not low) in self-ascribed masculinity indicated preference for an ideal partner to possess feminine traits, whereas for men with low internalized stigma, self-ascribed masculinity did not predict preference for partner’s feminine traits. The alternate hypothesis—i.e., that men’s self-ascribed femininity would predict wanting a masculine-typed partner—did not yield any reliable results as a function of stigma. Similarly, women did not show any indication of wanting a partner who “complemented” them in terms of personality traits as a function of stigma.

The results from this study mostly reflect findings from other work (e.g., Hsu et al., 2021) that gay and lesbian individuals, on average, want partners that are similar to themselves in terms of personality. Both men and women who self-describe as feminine show preferences for partners with feminine traits, and those who self-describe as masculine show preferences for partners with masculine traits. Only “high masculine” men with high internalized stigma disrupted this pattern of similarity.

One unexpected interaction emerged, namely, that women’s self-ascribed masculinity was positively associated with wanting a like-minded (i.e., masculine) partner among those low in stigma, but self-ascribed and partner masculinity were unrelated among women with high stigma. Although this interaction was not predicted, it is in line with the idea that stigma would lead to preferences for gender complementarity, such that those low (vs. high) in stigma appear to be especially likely to avoid it. This result could be an indication that stigma is serving to suppress women’s desire for a similar (and similarly gender atypical) partner.

In looking at the division of household chores, we did not find that stigma led to gender complementarity overall. Instead, the pattern of results shows that that internalized stigma is associated with the avoidance (or outsourcing) of gender incongruent chores. Specifically, among women, stigma was negatively related to a self- (vs. partner) preference to do masculine-typed household chores, but unrelated to women’s preferences for feminine-typed chores. Among men, stigma was negatively related to a self (vs. partner) preference for feminine-typed household chores, and unrelated to preferences for masculine-typed chores. Although it appears that men with high (vs. low) stigma and women with low (vs. high) stigma show preferences for a more gender complementary division of labor, this is driven by a desire to engage in gender congruent behaviors (and to outsource gender incongruent ones) among those who are high in internalized stigma. In a supplementary analysis, we examined self- versus partner preferences separately (see Sect. 4 of the online supplement), and the results suggest that stigma is affecting both self and partner preferences to some degree. In Study 2, we use a measure of household chore preference that directly pits self- versus partner preferences, so that we can avoid the use of difference scores, which introduce ambiguity and reduced reliability (Edwards, 2002).

The bivariate correlations from this study show that stigma is negatively associated with gender incongruent traits and tasks, which could be another indication that stigma suppresses gender atypical expressions. Specifically, men’s stigma was negatively related to self-ascribed femininity (but unrelated to self-ascribed masculinity) and to a self-preference for stereotypically feminine (but not masculine) tasks, whereas women’s stigma was negatively related to self-ascribed masculinity (but unrelated to self-ascribed femininity) and preference for stereotypically masculine (but not feminine) tasks.

It is important to note that we used a very narrow measure of masculinity and femininity in this study. This was by design, as we wanted to ensure that all participants viewed the traits in the same way, where their stereotypical masculinity and femininity was obvious (see supplementary materials). Thus, the stereotypical gendered-ness of these attributions—i.e., describing the self or partner as “rough” and “aggressive,” versus “sensitive,” “gentle,” and “delicate”—is very apparent in this study. However, they are admittedly limited measures. In Study 2, we use a different measure of masculinity and femininity, namely, the Bem Sex Roles Inventory (BSRI; Bem & Lenney, 1976). Although the validity of the BSRI has been debated over the years (e.g., Moradi & Parent, 2013; Morawski, 1987), it is a much broader assessment of masculinity/femininity than we used in Study 1, and it is commonly employed in research on gender stereotyping (e.g., Spence & Buckner, 2000).

In sum, the results from this first study are in line with the proposition that internalized stigma may manifest as a preference for gender complementarity in terms of personality traits in same-gender couples—but only among men that self-describe as masculine. In Study 2, we aim to hone in on this by examining self-descriptions and partner preferences in a different sample of gay men. We also aim to extend this finding by examining whether this preference for gender complementarity is affected by the perceptions of societal exclusion (or inclusion). Toward that end, Study 2 includes an experimental manipulation that presents the status quo as mostly hostile to same-gender relationships (“threat condition”) or mostly tolerant and accepting of same-gender relationships (“affirmation condition”), to test whether gay men with high stigma are more likely to embrace heteronormativity (in terms of relationship gender complementarity) when they are made to feel particularly excluded, and less likely when they are made to feel included.

Study 2

Study 2 provides a second examination of the associations between internalized stigma and partner preferences in a different sample of gay men, testing the hypothesis that, among gay men high in internalized stigma, those who rate themselves high (vs. low) in masculinity will prefer an ideal partner with feminine traits. Based on the results from Study 1, we do not expect a gender complementarity pattern to emerge among men who self-describe as feminine. In this study, we also examine preferences for the division of labor, but this was measured in a different way than it was in Study 1. Here, we asked participants to rate their preferences for the division of household chores on a single scale (assessing preference for the self vs. partner to do each chore). We predict that internalized stigma will be associated with gay men’s preference for a partner (vs. the self) to take on stereotypically feminine chores, but unrelated to preferences for who does the stereotypically masculine chores.

A second aim of Study 2 was to test whether seeking gender complementarity in same-gender relationships is motivated by the desire to feel accepted in (a heteronormative) society. Research has shown that relational needs, such as the need to belong, tend to elicit system-justifying attitudes and behaviors (Bahamondes et al., 2021; Hennes et al., 2012; Jost et al., 2018). Based on this, we predicted that making the societal exclusion (or inclusion) of same-gender couples salient would trigger (or quell) people’s need to belong, which would, in turn, heighten (or lower) their desire to emulate heteronormative relationship dynamics (a potentially system-justifying behavior). Because those who harbor stigma around their sexual orientation would presumably be the most sensitive to messages of inclusion or exclusion, we expected that the effects of the salience of societal exclusion on the desire for gender complementarity in ideal partners would be most apparent among those high (vs. low) on internalized stigma.

To examine this, we included a manipulation in Study 2 that was designed to affect people’s perceptions of the societal acceptance of same-gender relationships, with the intent of activating or satisfying a need to belong. More specifically, participants were randomly assigned to read one of three paragraphs that either (1) made salient anti-gay discrimination in America (“threat condition”); (2) highlighted the increased acceptance of gay people in America (“affirmation condition”); or (3) was a similar-length piece about an unrelated topic (i.e., an iPhone sleep application; “control condition”). We predict that the pattern of results we expect to find in the control condition—i.e., that gay men high on masculinity and internalized stigma will show a preference for gender complementary partners—will be exacerbated in the threat (vs. control) condition, and reduced or eliminated when the participants are told of the increasing social acceptance of non-heterosexuality (i.e., in the affirmation versus control condition).

Method

Participants

We aimed for at least 100 participants for each of the three conditions, and thus recruited 350 self-identified gay men from Amazon Mechanical Turk to participate in a study about same-gender romantic relationships. Because the manipulation was country-specific, we recruited only participants living in the United States. To make sure that participants were truthful about their sexual orientation, we asked participants to report their sexual orientation at the end of the study, ensuring them that they would receive credit for the study regardless of their response. At this point, seven participants reported that they identified as heterosexual or straight, and one participant indicated his sexual orientation as “other” (specifying “virgin”). Three additional participants were missing data on focal variables, precluding them from inclusion in the analyses. Thus, our final sample size included 339 gay male participants.

Sensitivity analyses conducted with G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007) showed that for power (1 − β) of .80 and a significance level of .05, our sample size was sufficient for detecting the predicted masculinity-by-stigma interaction with a critical F(1, 321) = 3.87, and the three predicted interactions (masculinity-by-stigma, and its interactions with the threat and affirmation conditions) with a critical F(3, 321) = 2.63 in a linear regression model.

The majority (70.5%) of the sample was White, non-Hispanic (n = 239). The remainder of the sample identified as: Hispanic/Latinx (n = 36); Black (n = 32); multi-racial (n = 10); Asian (n = 4); and Native American (n = 3). The average age was 29.40 years (SD = 8.72; with ages ranging from 18 to 67 years old), and 45.7% (n = 155) of participants had a college degree or higher. Using a slider that ranged from 0 to 100, participants indicated their “social position relative to other people in the U.S.” (M = 51.91, SD = 23.02). In terms of relationship status, 33.3% (n = 113) of the sample was single; 31.0% (n = 105) were living with their partner; 28.9% (n = 98) were in a non-cohabitating committed relationship; 4.7% (n = 16) were legally married, and the remaining participants were separated (n = 2), divorced (n = 4), and widowed (n = 1).

Participants were first presented with the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI; see Bem & Lenney, 1976), where they were asked to rate themselves on a list of 60 traits (20 stereotypically masculine, 20 stereotypically feminine, and 20 non-gendered). Participants were then randomly assigned to read one of three paragraphs, ostensibly taken from a recent New York Times article (see supplementary materials for the full text). Those in the threat condition (n = 116) read about the discrimination and animosity that gays and lesbians continue to face; those in the affirmation condition (n = 112) read about the progress that has been made with respect to gay and lesbian societal acceptance; and participants in the control condition (n = 111) read about an iPhone sleep application. Following the manipulation, participants responded to items assessing their need to belong (as a manipulation check) and their internalized stigma. They then answered questions about their relationship ideals (with the same instructions to “imagine [their] absolute ideal romantic relationship” as in Study 1), including BSRI trait ratings of their ideal partner, and their preferences for the division of household labor in the relationship (measured slightly differently in Study 2, see below).

At the end of the study, participants were told the full purpose of the study, and it was made clear that the passage that they read was fabricated by the researchers. They were provided with a link to a report by Pew Research Center with accurate information about public opinion on LGBT rights. This study was reviewed and approved by the first author’s institutional review board for compliance with standards of the ethical treatment of human participants.

Measures

For each scale, items were averaged, with higher numbers indicating higher scores for each construct.

Masculinity and Femininity Ratings of Self and Ideal Partner

Participants rated themselves and their ideal partner on 60 traits included in the BSRI (20 of which are deemed “masculine” traits; 20 as “feminine” traits; and 20 as gender-neutral traits), recorded on a scale from 1 (never or almost never true) to 7 (always or almost always true). We computed the mean of the 20 masculine traits to create a stereotypical masculinity score for both the self (α = .92) and the ideal partner (α = .92). Similarly, we computed the mean of the 20 feminine traits to create a stereotypical femininity score for both the self (α = .88) and the ideal partner (α = .87).

Need to Belong

Participants responded to 10 items (α = .79) measuring their need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; e.g., “I want other people to accept me”), with responses recorded on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Internalized Sexual Stigma

Participants responded to 20 items (α = .91) assessing their degree of internalized sexual stigma (Wagner, 2011), with responses recorded on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Division of Household Labor

Participants rated the same five masculine-type tasks (α = .75) and four feminine-type tasks (α = .75) as in Study 1. In this study, however, they rated these on a single scale with responses ranging from 1 (I would do this all of the time) to 5 (My partner would do this all of the time), with the scale midpoint (3) labeled: We would do this equally.

Results

Table 3 lists the means and standard deviations and bivariate correlations among the focal variables. Using this broader measure of masculinity/femininity, we find more positive associations between self and partner masculinity/femininity ratings compared to Study 1, suggesting the need to examine their independent effects in a multiple regression model. However, the bivariate correlations do indicate that most participants prefer partners with traits that are similar to their own—i.e., self-ascribed masculinity was positively correlated with wanting a partner with masculine traits, and self-ascribed femininity was positively correlated with wanting a partner with feminine traits—mirroring the findings from Study 1. Also mirroring Study 1, correlations show that men’s stigma was positively associated with a preference for a partner to do feminine tasks, but unrelated to a preference for masculine tasks.

To ensure that the manipulation did not impact participants’ internalized stigma, we conducted a one-way ANOVA to examine stigma scores as a function of condition. Results showed there was no effect of condition on internalized stigma, F(2, 336) = 1.22, p = .297, and scores were roughly equal across the threat (M = 2.16, SD = 0.92), affirmation (M = 2.26, SD = 1.00), and control (M = 2.06, SD = 0.92) conditions, Bonferroni-adjusted p-values all > .350.

To test whether the manipulation affected participants’ need to belong, especially among those high on internalized stigma, we conducted a 2-step regression model with two dummy codes for condition (i.e., threat vs. control and affirmation vs. control) in Step 1, and adding internalized stigma and its interactions with condition in Step 2. Results from Step 1 showed that the manipulation had little effect on need to belong—i.e., those in the threat (vs. control) condition scored slightly (but not significantly) higher, b = .14, SE = .08, p = .083, and those in the affirmation (vs. control) condition scored roughly the same, b = .08, SE = .08, p = .321. Results from Step 2 further revealed no interactions between internalized stigma and condition, including the threat (vs. control) condition, b = -.03, SE = .12, p = .807, and the affirmation (vs. control) condition, b = -.05, SE = .12, p = .688. Thus, the manipulation did not affect people’s need to belong, regardless of their level of internalized stigma.

Partner Traits

To test our hypothesis, we conducted a stepwise multilevel linear regression model predicting the ideal partner’s traits, with trait type (feminine = 0 and masculine = 1) as a within-subjects variable and self-ascribed masculinity and femininity (mean-centered), internalized stigma (mean-centered), and the interactions between masculinity and femininity with stigma as between-subjects variables, allowing for a random slope of trait-type. Thus, the first step of the regression model is the same model we tested in Study 1. In a second step, we added the experimental conditions (two dummy codes for threat vs. control and affirmation vs. control) and all of the interactions between self-ascribed femininity, self-ascribed masculinity, internalized stigma, and trait type and the two experimental conditions.

In Step 1, there was a positive effect of trait type, such that people preferred partners with more masculine (vs. feminine) traits overall, b = .15, SE = .04, p < .001. This was qualified by interactions with masculinity, b = .24, SE = .05, p < .001, femininity, b = -.33, SE = .05, p < .001, and internalized stigma, b = -.24, SE = .06, p < .001, and a 3-way interaction between trait type, masculinity, and stigma, b = -.13, SE = .06, p = .039.

In Step 2, we added the two conditions—threat (vs. control) and affirmation (vs. control) and their interactions will all the other variables in the model. For ease of presentation, Table 4 shows the simple slopes for predicting feminine traits (trait type = 0) and masculine traits (trait type = 1) separately (see Sect. 3 of the online supplement for full model). As can be seen in the table, the only effect of experimental condition to emerge was an interaction between threat and stigma, such that internalized stigma was positively related to wanting a partner with feminine traits in the control condition, b = .17, SE = .07, p = .028, but this was negative (and not significant) in the threat condition, b = -.12, SE = .08, p = .161. Beyond this, there was no effect of either the threat or affirmation condition (relative to the control condition), and no interactions between the experimental conditionals and femininity, masculinity, or internalized stigma, for predicting preferences for partners with feminine or masculine traits.

As seen in the first set of columns of Table 4, self-ascribed femininity was positively related to wanting a partner with feminine traits. There was also a (smaller) positive main effect of self-ascribed masculinity, which was qualified by the predicted masculinity-by-stigma interaction (see Fig. 3). An examination of the simple slopes of the predicted masculinity-by-stigma interaction revealed that self-ascribed masculinity predicts an ideal partner’s feminine traits among men high in stigma, b = .39, SE = .10, p < .001, but not among men low in stigma, b = .12, SE = .07, p = .105. Looking at it the other way, for men who rate themselves as low in masculinity, stigma is unrelated to a partner’s femininity, b = -.01, SE = .09, p = .921; for men high in masculinity, however, stigma is positively associated with wanting a partner with feminine traits, b = .36, SE = .12, p = .002.

As seen in the second set of columns of Table 4, self-ascribed masculinity and femininity are both positively related to wanting a partner with masculine traits. There was also a main effect of stigma, such that men high (vs. low) in internalized stigma are less likely to want a partner to have stereotypically masculine traits, but this was not qualified by self-ascribed femininity or masculinity.

Estimate of Effect Size

As in Study 1, we conducted a linear regression model predicting preference for a partner’s feminine traits with the focal predictors, finding that the F-change associated with adding the masculinity-by-stigma interaction was F(1, 333) = 5.89 (when added in Step 1 of Table 4) and F(1, 321) = 6.01 (when added to the model in Step 2 of Table 4). Both of these statistics exceeded the critical value of F(1, 321) = 3.87.

Division of Household Labor

We next examined participants’ self (vs. partner) preferences for household tasks. We conducted a stepwise multilevel model predicting task preference with task type (masculine vs. feminine), internalized stigma, and their interaction (Step 1), and experimental conditions and their interactions with stigma and task type in Step 2.

Results from Step 1 showed that participants indicated a self- (vs. partner) preference for feminine (over masculine) chores, b = -.14, SE = .05, p = .003. Internalized stigma was negatively related to self-preference for (feminine) chores, b = -.17, SE = .06, p = .001, and this was qualified by chore type, b = .22, SE = .07, p = .002. As detailed in the supplementary materials (see Sect. 3 in the online supplement), there were no main or interactive effects of the experimental condition in Step 2, but these main effects and interaction remained significant (see Fig. 4).

Analyses of the simple slopes showed that stigma was inversely related to a self (vs. partner) preference for feminine chores, b = -.19, SE = .08, p = .002, but unrelated to preferences for masculine chores, b = .06, SE = .09, p = .489.

General Discussion

Across two studies, we examined how internalized stigma and gendered trait ascriptions relate to partner preferences for lesbian women (Study 1) and gay men (Studies 1–2). Overall, both studies provide evidence consistent with previous work, such that, on average, participants in our studies indicated preferences for romantic partners who are similar to themselves (in terms of stereotypical masculinity and femininity; Bartova et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2021), and for an egalitarian division of labor at home (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007; Solomon et al., 2005). Even though many heterosexual individuals may expect same-gender couples to emulate traditional gender roles (e.g., Doan & Quadlin, 2019), our data suggest that, by and large, most same-gender couples will defy these expectations.

Importantly, the current studies highlight how internalized stigma disrupts this pattern of egalitarianism—at least for men who self-describe as masculine. In Study 1, we found that among those with high (vs. low) internalized stigma, men (but not women) who self-describe as masculine indicate preferences for a partner with feminine (i.e., “gender complementary” traits). This exact same pattern of results emerged in Study 2, which used a different sample of gay men and different measures of stereotypical feminine and masculine traits. We did not find evidence of gender complementarity among men who self-describe in stereotypically feminine ways in either study. Although we predicted that we would find gender complementarity for people high (vs. low) in stigma, we suspected this might especially be the case for men who self-describe as stereotypically masculine, and the data show that was the case.

We did not find evidence that internalized stigma was associated with gendered divisions of household labor in either Study 1 or Study 2. Instead, the data show that people with relatively high internalized stigma report lower willingness to engage in gender incongruent behavior. More specifically, in Study 1, we found that men’s internalized stigma was negatively associated with self (vs. partner) preferences to do stereotypically feminine (but not masculine) household chores and women’s internalized stigma was negatively associated with self (vs. partner) preferences to do stereotypically masculine (but not feminine) household chores. Data from Study 2, which only included male participants, replicated this pattern, such that men’s internalized stigma was negatively related to a self (vs. partner) preference to do stereotypically feminine chores, but unrelated to preferences for stereotypically masculine chores.

In supplementary analyses, we examined whether personality traits predicted partner (vs. self) preferences for household chores, but the results from these analyses were inconsistent (see Sect. 5 of the online supplement). Thus, the primary take-away from this research is that gay men (but not lesbian women) who harbor stigma about their sexual orientation and are high in self-ascribed stereotypical masculinity tend to prefer partners with gender complementary (i.e., stereotypical feminine) traits. Further, internalized stigma appears to manifest in behavioral preferences in the home, such that men and women high (vs. low) in internalized stigma show a preference for their partner (rather than themselves) to do gender incongruent household chores.

In Study 2, we predicted that gay men’s preference for gender complementarity might be affected by the salience of societal discrimination (“threat”) or acceptance (“affirmation”), but there was no evidence for this in our data. We did not find any effects of threat or affirmation on preferences for partner’s personality traits or household chores. That is, the gender complementary pattern of men high in stigma with high self-ascribed masculinity preferring partners with feminine traits emerged, and to the same extent, across all three conditions (threat, affirmation, and control). In addition, the negative association between internalized stigma and self-preference for feminine chores emerged to the same extent across the three conditions.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

In sum, our data are consistent with the proposition that gender role complementarity (in terms of personality traits) is a desired relationship feature only to the extent that same-gender relationships are socially stigmatized, insofar as we find it only emerges among self-described masculine man who are high (but not among those who are low) in internalized stigma. However, we do not have any causal evidence for this, insofar as the manipulation did not affect the pattern of results.

Perhaps this was something that we ought to have expected. The idea that gay men’s sense of belonging can be impacted by reading a paragraph about societal discrimination toward their group may be far-fetched. Our participants have had a lifetime of experiences that vary depending on their age, social networks and family background, and geographical locations (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, 2011, 2014), which are undoubtedly more powerful forces in shaping their perceptions of discrimination, as well as their preferences and values. For this reason, we did not predict (nor did we find) that our manipulation would impact gay men’s level of sexual stigma, which is likely a deeply ingrained individual difference. What our results do show rather consistently is that internalized stigma is associated with desiring partners with more stereotypically feminine traits among men who self-describe as fairly masculine. We think this is in line with the broader proposition that the emulation of heteronormative dynamics in same-gender relationships is likely a system-justifying response to societal marginalization.

Data from both studies indicate that internalized stigma is negatively associated with gender incongruent tasks—i.e., men who are high (vs. low) in stigma appear to avoid doing stereotypically feminine household chores (but stigma was unrelated to preferences for stereotypically masculine chores), and women who are high (vs. low) in stigma appear to avoid doing stereotypically masculine household chores (but stigma was unrelated to preferences for feminine chores). This relates to other work showing that men with high (vs. low) internalized stigma are more likely to overemphasize their masculinity (e.g., Kimmel & Mahalik, 2005; Sánchez & Vilain, 2012; Thepsourinthone et al., 2020; Zheng & Fu, 2021) and present as “straight acting” (Hunt et al., 2020). However, the pattern that emerged in our work suggests a somewhat different process—namely, that men’s stigma appears to be more strongly associated with the avoidance of femininity (see also Sánchez & Vilain, 2012) rather than the embracement (or exaggeration) of masculinity. Previous research had only examined this among men. In the current work, we find that for both men and women, internalized stigma is associated with the avoidance of gender incongruent behaviors, but not an amplification of gender typical ones, at least when it comes to household chores. This might indicate that internalized stigma among gay men and lesbian women might manifest as a suppression of gender atypical behavior more generally—an interesting next step for future research.

Beyond internalized stigma, there is good evidence that gay men modify their public expressions (e.g., changing their mannerisms and tone) because of a fear of sexual prejudice (Pachankis, 2007). It is likely that stigma even further heightens individuals’ aspiration to “pass” as straight (Hunt et al., 2020), which also presumably would lead people to want a straight-seeming (i.e., gender typical) partner. Some research (again, solely on gay men) supports this notion, such that internalized stigma is positively associated with preference for partners who appear and act masculine (Sánchez & Vilain, 2012). In the current research, our predictions about gender complementarity were limited to non-physical characteristics, and this may be an important caveat to our findings. In other words, our data show that high-stigma individuals sometimes want partners who complement them in personality, which presumably is more apparent in their private relationship dynamics. This dovetails with work showing that gay men with exclusively complementary sexual partner preferences tend to report higher internalized stigma than those who are more versatile (e.g., Zheng & Fu, 2021). This very well might not extend to desires for gender complementarity in appearance or more public behaviors, especially insofar as that would involve displays of gender atypicality.

These subtle considerations (e.g., public vs. private) highlight the complicated intersection of gender and sexuality, especially for men (Herek, 1986). More broadly, for gay people (especially men, for whom gender prescriptions are stricter; Vandello & Bosson, 2013), heteronormativity presents a conflict between conventional gender roles (where men act masculine) and conventional gender relations (where romantic partners are gender differentiated). Although we aimed to reduce this conflict in our studies, at least to some extent, by assessing relatively private relationship dynamics (personality traits and behaviors inside the home), a worthy next step for this research is to identify situational factors that systematically influence how attempts to assimilate to a heteronormative status quo are expressed. For instance, it is conceivable that self-ascriptions of masculinity/femininity are malleable, depending on the context. These contexts may be different, too, for gay men versus lesbian women.

Most social psychological work on sexual minorities excludes women, and thus very little is known about the unique ways in which internalized stigma may manifest in lesbian women. Consistent with previous work, we find that lesbian women report lower levels of internalized stigma (Herek et al., 1998) and lower preferences for a partner with masculine traits (Bailey et al., 1997), compared to gay men. Unfortunately, the current studies do not contribute very much beyond this, insofar as our predictions about gender complementarity only emerged among men.

There are theoretical explanations for why dyadic heteronormativity in same-gender relationships is exclusive to (stereotypically gender-typical) gay men. First, men’s beliefs about romantic relationships appear to be embedded in their broader sociopolitical ideologies, whereas women’s do not. For instance, a series of studies showed that threatening the sociopolitical system led heterosexual men (but not women) to defend heteronormative relationships, and, conversely, depicting the heteronormative status quo as unstable (vs. stable) led men (but not women) to defend the sociopolitical system (Day et al., 2011). It seems conceivable, then, that system justification tendencies (such as chronic internalization of stigma) may not manifest in women’s romantic relationship dynamics (see also, Pacilli et al., 2011), but might surface in other ways (e.g., self-objectification; Calogero & Jost, 2011, or perfectionism; Pachankis & Hatzenbuehler, 2013).

Second, compared to women, men are more attuned to, and supportive of, social hierarchies (Eagly et al., 2004; Sidanius et al., 2000). Insofar as heteronormativity is essentially a power arrangement, it may be more appealing to men than to women. In line with this idea, gay (vs. lesbian and heterosexual) couples have larger discrepancies in age, income, and education level; further, there is a strong relationship between income and partner dominance in gay men, but no relationship in lesbian couples (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007). One fascinating direction for future research is to examine whether status differences (e.g., job prestige, age, or income) between same-gender romantic partners affect gendered behavior in the relationship or vice-versa (Eagly & Steffen, 1984; Jost & Hamilton, 2005). It is conceivable, for instance, that the lower status partner tends to take on more stereotypically feminine household tasks or even more submissive sexual practices, and perhaps especially among men (vs. women).

Practice Implications

The results from our studies show that harboring stigma about one’s sexuality may manifest in same-gender relationship dynamics. Specifically, gay men (but not lesbian women) who are high (vs. low) in internalized stigma and self-describe as high in masculinity rate their ideal partners as ones who are high (vs. low) in stereotypically feminine traits. This may indicate that some men who have internalized stigma around their sexual orientation end up in relationships based on some notion of a gendered schema, and perhaps risk overlooking deeply compatible partners who do not fit into this schema. It might also be the case that heteronormative personality dynamics among same-gender couples could be an indication that at least one member of the couple (especially the stereotypically masculine one, based on our data) harbors internalized stigma.

We also find that gay men and lesbian women who are high (vs. low) on internalized stigma indicate a desire to avoid gender incongruent household chores—i.e., lesbian women high on stigma indicate wanting a partner (vs. the self) to do stereotypically masculine chores (e.g., taking out the trash), and gay men high on stigma indicate wanting a partner (vs. the self) to do stereotypically feminine chores (e.g., cooking and cleaning). There has been much scholarly and public interest in the division of labor of same-gender couples (e.g., Brewster, 2017; Carrington, 1999; Miller, 2018; Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007; van der Vleuten et al., 2020), but very little speculation about whether psychological factors can help explain people’s proclivities for household chore division. Our data suggest that internalized stigma might be an important consideration in understanding the division of household labor among same-gender couples.

Conclusion

The increased visibility of same-gender relationships and families offers a new light in which to explore the constructs of gender, gender roles, and heteronormativity. In the current work, we report data showing that gay men’s (but not lesbian women’s) personal preferences for relationship partners are, to some extent, political: those who have internalized their relatively low societal status are inclined to seek relationships that align with the heteronormative status quo, at least for men high in masculinity. This finding thus adds to a body of evidence showing the subtle ways that members of oppressed groups serve to bolster the dominant ideologies that subjugate them (Jost et al., 2004; Pacilli et al., 2011).

In her response to accusations that consciousness-raising groups for women’s liberation were “personal therapy,” Carol Hanisch (1969) wrote that: “therapy assumes that someone is sick and that there is a cure, e.g., a personal solution… Women are messed over, not messed up! We need to change the objective conditions, not adjust to them” (p. 3). In line with this assertion, we contend that gay men and lesbian women who harbor stigma about their sexual orientation have indeed been messed over. Attempts to emulate or embody heteronormative values—including efforts to promote gender typicality in the self or gender complementarity in relationships—are not indications of personal shortcomings, but byproducts of an oppressive system that needs to be radically restructured.

Data Availability

Data and SPSS syntax files are available at https://osf.io/58v4b/.

References

Allport, G. W. (1979). The nature of prejudice. Perseus Books.

Bailey, J. M., Kim, P. Y., Hills, A., & Linsenmeier, J. A. W. (1997). Butch, femme, or straight acting? Partner preferences of gay men and lesbians. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 960–973. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.960

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bartova, K., Sterbova, Z., Novakova, L. M., Binter, J., Varella, M. A. C., & Valentova, J. V. (2017). Homogamy in masculinity-femininity is positively linked to relationship quality in gay male couples from the Czech Republic. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 1349–1359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0931-z

Bem, S. L., & Lenney, E. (1976). Sex typing and the avoidance of cross-sex behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33, 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0078640

Berg, R. C., Munthe-Kaas, H. M., & Ross, M. W. (2016). Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Journal of Homosexuality, 63, 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788

Bahamondes, J., Sengupta, N. K., Sibley, C. G., & Osborne, D. (2021). Examining the relational underpinnings and consequences of system-justifying beliefs: Explaining the palliative effects of system justification. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(3), 1027–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12440

Boyden, T., Carroll, J. S., & Maier, R. A. (1984). Similarity and attraction in homosexual males: The effects of age and masculinity-femininity. Sex Roles, 10, 939–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00288516

Brewster, M. E. (2017). Lesbian women and household labor division: A systematic review of scholarly research from 2000 to 2015. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 21, 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2016.1142350

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble. Routledge.

Calogero, R. M. (2013). On objects and actions: Situating self-objectification in a system justification context. In: Gervais, S. (Ed.) Objectification and (de)humanization. Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol 60, pp. 97–126). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6959-9_5

Calogero, R. M., & Jost, J. T. (2011). Self-subjugation among women: Exposure to sexist ideology, objectification, and the protective function of the need to avoid closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2, 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021864

Carrington, C. (1999). No place like home: Relationships and family life among lesbians and gay men. University of Chicago Press.

Cass, V. C. (1979). Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4, 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v04n03_01

Dahl, J., Vescio, T., & Weaver, K. (2015). How threats to masculinity sequentially cause public discomfort, anger, and ideological dominance over women. Social Psychology, 46, 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000248

Day, M. V., Kay, A. C., Holmes, J. G., & Napier, J. L. (2011). System justification and the defense of committed relationship ideology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023197

Deaux, K., & Major, B. (1987). Putting gender into context: An interactive model of gender-related behavior. Psychological Review, 94, 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.369

Doan, L., & Quadlin, N. (2019). Partner characteristics and perceptions of responsibility for housework and child care. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(1), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12526

Dunne, G. A. (1997). Lesbian lifestyles: Women’s work and the politics of sexuality. University of Toronto Press.