Abstract

Numerous studies have demonstrated the harmful effects of sexual objectification on well-being. However, despite the rapid growth of the #MeToo movement, which has raised public awareness about sexual harassment, there has been much less research investigating the role of sexually objectifying behaviours in motivating people to try to tackle this issue through collective action (e.g., signing petitions, engaging in protests) and the process through which this occurs. Across two studies, we tested whether experiencing sexually objectifying behaviours motivates women to be willing to engage in collective action against sexual objectification via feelings of anger toward women being the target of such actions (i.e., group-based anger). In Studies 1 (n = 127) and 2 (n = 159), female participants rated the extent to which they had been the target of sexually objectifying behaviours, their feelings of group-based anger, and their willingness to engage in collective action against sexual objectification. We found that sexual objectification positively predicted the willingness to engage in collective action and that this relationship was mediated by feelings of group-based anger. This pattern suggests that experiencing numerous instances of sexual objectification is likely to result in women feeling group-based anger and that this anger, in turn, promotes collective action against sexual objectification. Therefore, our research demonstrates one process through which sexual objectification promotes a willingness to engage in collective action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sexual objectification involves being regarded as a sexual object rather than a human being and may occur through a variety of actions, including receiving inappropriate comments, sexualized gazing, or being groped. Sexual objectification is commonly experienced by women (Holland et al. 2017; Swim et al. 2001) and is prevalent in numerous situations, ranging from education and work to commuting and social settings (Brinkman and Rickard 2009; Fairchild and Rudman 2008). Experiencing sexually objectifying behaviours has led to numerous women undertaking collective action against sexual objectification, as demonstrated by the #MeToo Movement. Indeed, across the world there have been petitions, activist organisations, social media campaigns, and protests designed to tackle sexual objectification. The aim of this research was to assess the process through which experiencing sexual objectification promotes collective action.

Objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997) suggests that women are frequently objectified within society, either through the mass media or as targets of sexually objectifying behaviours. According to this theory, this constant exposure to objectification has the potential to cause women to internalise this perspective and evaluate themselves based on their physical appearance. This theory suggests that when this self-objectification occurs it increases appearance-related concerns and thus the likelihood of women developing various mental health conditions, such as eating disorders and depression. Although this theory focuses on the role of self-objectification on well-being, researchers have assessed the influence of self-objectification on women’s perceptions and behaviours in other domains. Indeed, it has been argued that self-objectification may result in targets internalising negative societal views of their group and thus accepting their low status position (Calogero and Jost 2011; Zurbriggen 2013). In line with this reasoning, research has suggested that self-objectification positively predicts the belief that gender relations are fair and that this belief, in turn, reduces the likelihood of women engaging in collective action against gender inequality (Calogero 2013; Calogero et al. 2017). As such, this research suggests self-objectification deters collective action.

It is important to note that objectification theory suggests that sexual objectification does not always result in self-objectification. Indeed, experiencing sexual objectification may elicit a variety of responses (Fairchild and Rudman 2008; Shepherd 2019). These studies focus on interpersonal responses to sexual objectification. We aimed to extend this research by assessing collective responses to sexual objectification, such as the willingness to engage in collective action against sexual objectification. Research has found that experiencing other forms of gender discrimination motivates women to engage in collective action (Iyer and Ryan 2009; Leonard et al. 2011) and that observing others being sexually objectified motivates women to undertake action against sexual objectification (Chaudoir and Quinn 2010; Guizzo et al. 2017). Therefore, although self-objectification may deter collective action, personally experiencing sexual objectification may promote collective action. We argue that experiencing sexual objectification is likely to promote collective action through the emotions that are elicited.

Emotional Reactions to Sexual Objectification

Emotions are elicited when the interpretation of the situation matches an emotional appraisal (Frijda et al. 1989). Indeed, anger is felt when people make the appraisal that they have been subjected to a harmful illegitimate action (Smith and Lazarus 1993). For example, targets of sexual objectification are likely to feel angry when they view this action as harmful and illegitimate (Shepherd 2019; Swim et al. 2001). This previous research has focused on feelings of interpersonal anger following sexual objectification. However, it is also possible to experience group-based emotions through the association with a group (Doosje et al. 1998; Smith 1993). Indeed, group-based anger is felt when people believe that their group (e.g., women) have been the target of a harmful illegitimate action (Gordijn et al. 2001; Leach et al. 2002). For example, research has suggested that women are likely to feel group-based anger following gender discrimination (Iyer and Ryan 2009; Pennekamp et al. 2007). Given this association, it is likely that sexual objectification also will elicit group-based anger.

Anger is an action-orientated emotion that motivates the individual to try to resolve the injustice (Frijda et al. 1989). For example, feeling interpersonal anger toward sexual objectification motivates the target to confront the perpetrating individual (Shepherd 2019). Interestingly, when group-based anger is experienced, people are likely to confront the perpetrating group and are therefore likely to engage in some form of collective action (Van Zomeren et al. 2008; Van Zomeren et al. 2004). Indeed, numerous studies have demonstrated the role of group-based anger in promoting collective action (Leonard et al. 2011; Livingstone et al. 2009; Tausch et al. 2011).

Importantly, these processes have been demonstrated in the objectification literature. For example, Chaudoir and Quinn (2010) found that witnessing sexually objectifying behaviour toward others motivates women to take action and that this is due to feelings of group-based anger. Similarly, watching a video criticising sexual objectification by the media promotes collective action through feelings of group-based anger (Guizzo et al. 2017). Therefore, it is likely that sexual objectification will promote collective action through feelings of group-based anger.

The Present Studies

As we mentioned, previous research has assessed the role of self-objectification on collective action (Calogero 2013; Calogero et al. 2017) or the role of mass media objectification on collective action (Guizzo et al. 2017). However, despite the strong theoretical rationale, to our knowledge there is little research assessing whether personally experiencing sexual objectification promotes collective action via feelings of group-based anger. This was the aim of the current research. We hypothesised that experiencing sexually objectifying behaviours would increase feelings of group-based anger and that these feelings, in turn, would promote a willingness to engage in collective action against sexual objectification. This hypothesis was tested across three studies. A pilot study assessed whether, in line with our rationale, experiencing sexual objectification promoted a willingness to engage in collective action. Studies 1 and 2 then tested our hypothesised model by determining whether group-based anger mediated this relationship.

Pilot Study

The main aim of our Pilot Study was to test whether being sexually objectified promotes collective action against the objectification of women. As such, the primary variables of interest were sexual objectification and the willingness to engage in collective action. However, the collective action literature suggests that people are also likely to take action when they feel others support their opinion (i.e., social opinion support; Van Zomeren et al. 2004). Feeling that others have also been sexually objectified may encourage women who have experienced objectification to take action. Therefore, our Pilot Study also aimed to see whether this relationship was moderated by social opinion support.

It is also important to ensure that any relationship between sexual objectification and the willingness to engage in collective action is not due to other variables. For example, people are more likely to engage in collective action when they believe others will also want to take action (i.e., social action support; Van Zomeren et al. 2004). As such, it was important to determine that any effect of sexual objectification or the social opinion support variable was not due to this social action support. Similarly, sexual objectification is positively associated with body shame (Kozee et al. 2007) and negatively associated with self-esteem (Tylka and Sabik 2010). Therefore, it was also important to test whether sexual objectification predicted the willingness to engage in collective action after controlling for these variables.

Method

Participants and Design

Participants were recruited for the present online study via adverts on social media websites and a course-credit system. The study was advertised as investigating the relationship between the objectification of women and collective action. To take part, participants had to be 18 years-old or older, female, and must not have been diagnosed with an eating disorder. A total of 149 women started our study. Twelve participants withdrew before the end of the study and were thus removed from the sample, leaving a total of 137 women, aged between 18 and 49 years (M = 21.62, SD = 5.26). Participants were most likely to be students (n = 112, 81.75%). There were similar numbers of women who were single (n = 66, 48.18%) and in a relationship (n = 70, 51.09%; 1 participant was divorced/separated).

The study had a two (social opinion support manipulation: control versus experimental) by continuous variable (perceived sexual objectification) between-participants design. The dependent variable was the women’s willingness to engage in collective action against sexual objectification. The covariates were participants’ perception that other women will want to take action against objectification (e.g., social action support), body shame, and self-esteem.

Materials and Procedure

After giving consent, participants completed the interpersonal sexual objectification scale (for full scale, see Kozee et al. 2007). This well-validated 15-item sexual-objectification measure assessed the extent to which participants felt that they had been objectified over the last year. This scale included items assessing sexual objectification related to both body evaluation (e.g., “How often have you been whistled at while walking down a street?”) and unwanted sexual advances (e.g., ‘How often has someone grabbed or pinched one of your private body areas against your will?’). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Almost Always). Ratings across all items were averaged to yield an overall measure of experiences of sexual objectification such that higher scores indicated greater levels of sexual objectification (α = .92).

We then manipulated social opinion support. All participants read the following information that defined sexual objectification and discussed sexual objectification in the media toward celebrities:

Objectification is the act of viewing someone as an object rather than a human being. This often occurs in the form of sexual objectification. This involves viewing a person (usually a women) as a sex object.

There are numerous factors that that been suggested to influence the objectification of women. For example, women are often objectified in the mass media through adverts, films, and television shows. Indeed, a recent report assessed 11 British newspapers and found that there was excessive sexual objectification of women in the media. Moreover, Jennifer Lawrence, the Hunger Games star, has criticised the media for their objectification of women, and their criticism regarding her appearance. She refers to it as "like being in high school" and suggests that the media are bad role models for young people by making them think it is "OK to point at people and call them fat or ugly."

Emma Watson has also recently spoken out on sexualisation and objectification. In her powerful speech regarding the issue, she discussed how she had been "sexualised by certain elements of the press since the age of 14" and how "girlfriends dropped out of sports teams due to the fear of appearing muscular" and not fitting the social stereotype of how femininity and the female body should look. This demonstrates the objectification that has been felt some celebrities.

Participants were then randomly allocated into the control or experimental condition. Participants in the experimental (but not the control) condition then read additional information that emphasised the prevalence of sexual objectification:

Research has found that the vast majority of women feel that they have been objectified. A recent study has found that 94% of female students reported unwanted sexual comments or behaviours at least once over the previous semester. Similar rates of objectification are likely in the general population. This demonstrates the prevalence of sexual objectification toward women. Indeed, most women seem to have experienced sexual objectification in the recent past.

Following this experimental manipulation, all participants completed a two-item manipulation check. These items were: “I think other women are likely to feel objectified” and “I think other women are likely to have been objectified” (see Van Zomeren et al. 2004). These items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The ratings of these items were averaged to create a measure in which higher scores reflected a greater belief that other women had been objectified (r = .60, p < .001).

Next, we measured three covariates. First, participants completed the following two items assessing social action support: “I think other women will want to do something against the objectification of women” and “I think other women will want to show their opposition to the objectification of women” (see Van Zomeren et al. 2004). These items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Ratings of these items were averaged to create an overall measure of social action support in which higher scores indicated a greater belief that other women will want to take action against sexual objectification (r = .71, p < .001). Second, participants completed a well-validated single-item measure of self-esteem (“I have high self esteem”), rated on a scale from 1 (Not very true of me) to 5 (Very true of me) (see Robins et al. 2001). Third, this measure was followed by an eight-item body shame scale (for full scale, see McKinley and Hyde 1996). These items included “I feel ashamed of myself when I haven’t made the effort to look my best,” “I would be ashamed for people to know what I really weigh,” and “I never worry that something is wrong with me when I am not exercising as much as I could” (reverse scored). These items were rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The average rating across these items was used to create an overall measure of body shame in which higher scores indicated greater body shame (α = .87).

Participants then rated their willingness to engage in collective action against the objectification of women. This seven-item measure assessed whether participants would wear a badge, join a Facebook group, join a protest, begin a petition, sign a petition, buy and wear a band, and join an email list against the objectification of women. Each item was rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (Definitely Not) to 7 (Definitely). The ratings of these items were averaged to create a measure in which higher scores indicated a greater willingness to engage in collective action (α = .93).

Statistical Analysis

First, we used ANOVAs to assess the effect of the social opinion support manipulation on the variables. Following this, we used correlation and linear regression analyses to assess the relationship between sexual objectification and the willingness to engage in collective action. Finally, the moderating role of social opinion support was assessed using the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013).

Results

Logarithmic transformations were applied to the manipulation check (i.e., social opinion support) and social action support variables to correct for outliers. Prior to these transformations the means for the social opinion and social action support variables were 4.01 (SD = .66) and 3.87 (SD = .78), respectively.

Effect of Social Opinion Support

ANOVAs were then undertaken to determine the effect of the manipulation on the manipulation check and the other variables. The manipulation did not have a significant effect on the manipulation check or any of the other variables (see Table 1). Therefore, this manipulation was not discussed further. However, in the subsequent analyses we are able to assess the influence of social opinion support using the measured manipulation check variable.

Association between Objectification and Collective Action

Next, correlation analyses were undertaken to assess the association between the variables. As hypothesised, the objectification measure was positively associated with willingness to engage in collective action against sexual objectification (see Table 2). The objectification measure was also positively associated with social opinion support and body shame. Moreover, the willingness to engage in collective action was also positively associated with social opinion and social action support. By contrast, body shame and self-esteem were not associated with collective action. These results suggest that sexual objectification was positively associated with collective action. However, given the association of these variables with the covariates, it was important to assess the unique predictive power of sexual objectification.

We used linear multiple regression analysis to assess the unique predictive power of the objectification measure on the willingness to engage in collective action after accounting for the covariates. This model account for 20% of the variance in the willingness to engage in collective action, F(5, 129) = 6.59, p < .001. Importantly, the objectification measure remained a significant positive predictor of collective action after accounting for the covariates (see Table 3). Interestingly, social action support positively, and self-esteem negatively, predicted collective action. All other covariates were not significant. Therefore, sexual objectification is a robust predictor of the willingness to engage in collective action.

Moderating Role of Social Opinion Support

Although the manipulation did not have a significant effect on the variables, it was possible to assess the moderating role of social opinion support using the manipulation check measure. As such, we assessed the interaction between the objectification and the social opinion support measure on the willingness to engage in collective action. This interaction was assessed using the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013; Model 1). In this analysis, there was a significant main effect of objectification (B = .49, SE = .18, p = .007) and social opinion support (B = 2.43, SE = .82, p = .004). However, the interaction between these variables did not have a significant effect on collective action (B = −1.34, SE = 1.26, p = .289). These results suggest the relationship between objectification and the willingness to engage in collective action did not vary based on social opinion support.

Discussion

Previous research has suggested that self-objectification is negative associated with collective action (Calogero 2013). In our study, we extended this research by demonstrating that experiencing sexual objectification was positively associated with the willingness to engage in collective action against the objectification of women. Importantly, this relationship remained significant after controlling for a series of covariates. Our findings suggest that experiencing sexual objectification motivates women to take collective action against sexual objectification. Interestingly, our social opinion support manipulation did not have a significant effect on the manipulation check variable. This nonsignificant effect may reflect the fact that the mean level of social opinion support was high. Indeed, the pre-transformation mean was 4 on a 5-point scale. This high mean may have made it difficult to manipulate this variable. Despite this shortcoming, further analysis revealed that the measured social opinion support variable did not moderate the relationship between sexual objectification and collective action. This non-finding may reflect the fact that the prevalence of sexual objectification may have resulted in the participants believing that most women are likely to have experienced sexual objectification and are thus willing to take action. Given this non-significant interaction, in the further studies social opinion support was treated as a covariate rather than a moderating variable.

The results from our Pilot Study were promising. However, it was important to assess the process through which the effect occurs. As we mentioned, we hypothesised that sexual objectification should promote a willingness to engage in collective action via feelings of group-based anger. We expected that experiencing sexual objectification should result in women feeling anger toward the treatment they receive by men and that this group-based anger should motivate women to engage in collective action. Therefore, it was important to extend the findings of the Pilot Study by testing this mediation model. This was the aim of Study 1.

Study 1

There were numerous differences between the Pilot Study and Study 1. First, as we mentioned, Study 1 measured group-based anger to test the mediation model. Second, Study 1 attempted to manipulate sexual objectification in order to establish causality. Based on previous research (Calogero 2013), participants in the objectified condition were asked to describe a time when they had been sexually objectified. By contrast, participants in the control condition were asked to describe the previous day. Based on research on the availability heuristic (Schwarz et al. 1991), we expected the experimental manipulation to increase the ease with which such examples come to mind and thus the perceived frequency of sexual objectification.

Third, Study 1 further tested the robustness of the findings by including additional covariates. Calogero (2013) suggested that self-objectification should deter collective action. As such, it was important to assess the role of this variable on the mediation model. Previous research also has suggested that collective action is predicted by the belief that the group will be effective in making a change (i.e., group efficacy; Van Zomeren et al. 2008). Therefore, we controlled for group-efficacy in Study 1. Moreover, although discrimination may promote group-based anger (Chaudoir and Quinn 2010; Iyer and Ryan 2009), the belief that this tarnishes the group’s image may also result in the elicitation of group-based shame (Matheson and Anisman 2009). Therefore, we also measured group-based shame.

Finally, research has suggested that although most women are likely to view sexual objectification negatively, some women may have a benign response and instead view such experiences positively (Fairchild and Rudman 2008; Liss et al. 2011). This reasoning suggests that it is possible that the relationship between sexual objectification and collective action may vary depending on the extent to which such actions are viewed as illegitimate. Therefore, we also assessed the moderating role of perceived illegitimacy.

Method

Participants and Design

Participants were recruited for this online study using adverts on social media and a course-credit system. The study was advertised as looking into women’s thoughts, feelings and actions toward objectification. Participants were required to be 18 years-old or older and female. For ethical reasons, participants were asked not to take part if they had an eating disorder or were likely to feel distressed when discussing instances of sexual objectification. We recruited 151 women for our study. We removed 24 participants for not completing the study, leaving a final sample of 127 women. Their age range was 18–41 years-old (M = 20.10, SD = 3.54). Participants were most likely to be students (n = 117, 92.13%). There were more single participants (n = 71, 55.91%) than participants in a relationship (n = 54, 42.52%; 1 participant was divorced/separated and 1 participant selected other).

The present study had a two conditions (sexual objectification: control versus objectified) by continuous moderating variable (perceived illegitimacy) between-participants design. The dependent variable was the willingness to engage in collective action. The mediating variable was group-based anger. The covariates were social opinion support, social action support, body shame, self-esteem, group-efficacy, and group-based shame.

Materials and Procedure

After giving consent, participants completed a four-item scale measuring perceived illegitimacy. The items were: “Objectifying women is wrong,” “Objectifying women is illegitimate,” “It is legitimate to objectify women” (reversed scored), and “It is ok to objectify women” (reverse scored). These items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The rating across these items was averaged to create a measure in which higher scores indicated greater perceived illegitimacy of objectification (α = .73).

Following this assessment, participants were randomly allocated into either the objectified or control condition. Participants in the objectified condition described a time when they had been objectified:

We would like to know your experiences of sexual objectification. Please think of a time when you have been sexually objectified. This may involve being whistled at, someone staring at parts of your body, or being touched against your will. In the box below, please describe a time when you have been sexually objectified. In this description please state when this occurred, who objectified you, how this occurred, and how you felt and responded to this.

In contrast, participants in the control condition described what they had done the previous day

We would like to know about your average day. Please think of what you did yesterday. In the box below, please describe what you did yesterday. In this description please state who you met during the day, what you did, and how you felt and acted.

We expected this manipulation to alter the perceived frequency of sexual objectification. As such, the interpersonal sexual objectification scale that we used in our Pilot Study was included as a manipulation check (Kozee et al. 2007). In line with the Pilot Study, the ratings across all items were averaged to create an overall measure of sexual objectification in which higher scores indicated greater sexual objectification (α = .91).

This sexual objectification scale was followed by the self-objectification measure (Noll and Fredrickson 1998). Participants were presented with ten traits relating to their physical self-concept. Five of these traits were related to the participant’s appearance (physical attractiveness, weight, sex appeal, body measurements, and firm/sculpted muscles), whereas the remaining five were more instrumental and thus not related to the participant’s appearance (health, strength, energy level, physical coordination, and physical fitness). Participants were required to rank the importance of each of these traits on their physical self-concept from 0 (least impact on my physical self-concept) to 9 (greatest impact on my physical self-concept). Typically, researchers obtain a measure of self-objectification by subtracting the sum of the instrumental trait rankings from the sum of the appearance trait rankings. However, using the sum of these traits is problematic because missing data have the potential to bias the participant’s score. Unfortunately, participants often finding this measure difficult to complete (Calogero 2011), increasing the likelihood of having missing data. Although for each of our participants the number of missing items was relatively small (M = .57, SD = 1.35), it was important to ensure that any missing data did not bias the results. To avoid this bias, we used the mean of the completed items rather than the sum of all items. We then subtracted the mean ranking for the instrumental from the mean ranking of the appearance-related traits to obtain a measure in which higher scores reflected greater self-objectification. Importantly, this score was highly correlated with the score obtained when using the sum of the traits (r = .93, p < .001), thereby creating an appropriate measure of self-objectification that is not bias by missing data.

Next, participants completed the two-item social opinion support (r = .67, p < .001) and social action support (r = .78, p < .001) measures used in our Pilot Study. The measure was calculated in the same way as in the Pilot Study. Participants then completed the group-based emotion measures. Because Study 1 aimed to assess group-based emotions, the wording of the items related to the ingroup (women) rather than the individual. As such, participants were asked: “The objectification of women makes me feel [emotion word].” The emotion words were angry, annoyed, furious, and outraged (Shepherd et al. 2013). The shame words were ashamed, disgraced, humiliated, and embarrassed (Schmader and Lickel 2006). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very much). An overall measure of each emotion was created by averaging the ratings of the emotion items (α = .96 for anger and α = .91 for shame). This created a measure in which greater scores indicated higher levels of the emotion.

Participants then completed a four-item group-efficacy scale. Based on previous research (Van Zomeren et al. 2004), the items were: “I think that together we are able to change the situation,” “I think that we are able to stop women being objectified,” “I think that we are unlikely to change the situation” (reverse scored), and “I think that we will not be able to stop women being objectified” (reverse scored). All items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very much). The ratings of these items was then averaged to create a measure in which high scores indicated greater group efficacy (α = .89). We then used the same measures from the Pilot Study to assess self-esteem (a single item), body shame (α = .89), and the willingness to engage in collective action (α = .92). In line with the Pilot Study, the average rating across all items was used to create the body shame and collective action measures.

Statistical Analysis

Initially, we conducted ANOVAs to assess the effect of the sexual objectification manipulation on the variables. Correlation analyses were then used to assess the association between the variables. Next, we used the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013) to assess the moderating role of perceived illegitimacy and our mediation model.

Results

We applied an inverse transformation to the perceived illegitimacy and social opinion support variables to correct for outliers. For similar reasons, a logarithmic transformation was applied to the social action support variable. Prior to these transformations, the means for these variable were 4.29 (SD = .65) for perceived illegitimacy, 4.37 (SD = .62) for social opinion support, and 4.09 (SD = .76) for social action support.

Effect of Objectification

Next, ANOVAs assessed the effect of the objectification manipulation on the objectification measure and other variables. The objectification manipulation did not have a significant effect on the objectification measure (see Table 4). Instead, this manipulation had a significant effect on social opinion support. The manipulation did not have a significant effect on the other variables. Given this manipulation only had a significant effect on a covariate and not the main variables of interest in our study, the effects of this manipulation were not discussed further. Instead, the objectification measure was used to assess the influence of sexual objectification on the willingness to engage in collective action.

Associations between Variables

Correlation analyses demonstrated that in line with the Pilot Study, the objectification measure was positively associated with the willingness to engage in collective action (see Table 2). Importantly for our mediation hypothesis, the objectification measure was also positively associated with group-based anger. The objectification measure was also positively associated with perceived illegitimacy, social opinion and action support, group-based shame, and body shame. Moreover, collective action was positively associated with group-based anger, further supporting our mediation hypothesis. Collective action was also associated with perceived illegitimacy, social opinion and action support, group-based shame, and group efficacy.

Moderating Role of Perceived Illegitimacy

Prior to testing our mediation hypothesis, it was important to assess the moderating role of perceived illegitimacy. This moderation was tested using the PROCESS macro (Model 1, Hayes 2013). For the collective action measure, there was a significant main effect of objectification (B = .71, SE = .17, p < .001) and perceived illegitimacy (B = 2.09, SE = .45, p < .001). However, the interaction between the objectification measure and perceived illegitimacy did not have a significant effect on the willingness to engage in collective action (B = −.13, SE = .67, p = .848). For the group-based anger measure, further analysis revealed a significant main effect of objectification (B = .59, SE = .13, p < .001) and perceived illegitimacy (B = 2.26, SE = .35, p < .001). However, the interaction between these two variables did not predict group-based anger (B = .05, SE = .52, p = .917). As such, these results found little support for the hypothesis that the role of sexual objectification on the willingness to engage in collective action was moderated by perceived illegitimacy.

Mediating Role of Group-Based Anger

Given the lack of evidence for moderation, we assessed a simple mediation model in which the relationship from sexual objectification (independent variable) to the willingness to engage in collective action (dependent variable) occurred via group-based anger (mediator). This model was assessed by calculating the 95% confidence intervals for the indirect pathway using 5000 bootstrap resamples (Hayes 2013). The regression model from this analysis revealed that sexual objectification positively predicted group-based anger and that this anger, in turn, positively predicted the willingness to engage in collective action (see Fig. 1). Interestingly, the direct pathway from the objectification measure to collective action became nonsignificant after controlling for group-based anger. Importantly, the confidence intervals did not contain zero for the indirect pathway (95% CI [.37, .87]). This pattern suggests a significant indirect effect from objectification to the willingness to engage in collective action via group-based anger.

It was important to test the robustness of the mediation model. This is especially important given the associations between the variables in this mediation model and the covariates. Therefore, these data were reanalysed with the covariates and the manipulation entered into the model. Importantly, the indirect effect remained significant after controlling for these variables (95% CI [.08, .44]). Interestingly, in this analysis group-based anger was the only variable to significantly predict the willingness to engage in collective action.

Given the correlational data, it could be argued that the reverse mediation model may be apparent in these studies (i.e., sexual objectification predicts group-based anger via collective action). Therefore, it was also important to test this reverse mediation model. The indirect effect for this reverse mediation model was significant in Study 1 (95% CI [.29, .68]). Therefore, although there is evidence for our hypothesised model, it is also important to consider the reverse mediation model (see Discussion).

Discussion

Study 1 supported the Pilot Study by demonstrating that sexual objectification is positively related to the willingness to engage in collective action. Moreover, Study 1 suggested that this relationship was mediated by group-based anger. Being objectified increased feelings of group-based anger, which in turn promoted a willingness to engage in collective action against the objectification of women. Importantly, this relationship remained after controlling for a series of covariates, demonstrating the robustness of the mediation model. It should be noted that we found statistical evidence for a reverse mediation model in which sexual objectification predicted group-based anger through collective action. However, despite this statistical rationale, there was not a strong theoretical rationale. Indeed, numerous studies have suggested that harmful actions predict collective action via feelings of group-based anger (Guizzo et al. 2017; Iyer and Ryan 2009; Van Zomeren et al. 2004). Therefore, the hypothesised model had a stronger theoretical rationale than this reverse mediation model.

Unfortunately, the objectification manipulation did not have a significant effect on the manipulation check (i.e., the perceived frequency of sexual objectification). It is possible that the manipulation was effective, but that we failed to find an effect because we used an inappropriate manipulation check. We may have found that the manipulation was effective if we used a different measure as the manipulation check. The absence of an appropriate manipulation check makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the manipulation. Indeed, we cannot determine whether the manipulation was simply ineffective and thus did not influence group-based anger or collective action, or whether the manipulation had a significant effect on sexual objectification but not the emotions or collective action. Because of this shortcoming, we used an established sexual objectification manipulation and manipulation check in Study 2 (Teng et al. 2015).

In Study 1, we found little evidence that perceived illegitimacy moderated the role of sexual objectification on the willingness to engage in collective action. This non-finding may be due to participants viewing sexual objectification as highly illegitimate, as demonstrated by the mean of this variable prior to the transformation (4.29 on a 5-point scale). This outcome is in line with other research demonstrating that although some women are likely to view sexual objectification positively (Liss et al. 2011), the majority of women view such actions negatively (Shepherd 2019). This negativity may have reduced the likelihood of perceived illegitimacy moderating the effects of sexual objectification.

Although the findings from Study 1 supported the hypothesised mediation model, it could be argued that the effects may be mediated by interpersonal anger rather than group-based anger. Indeed, it could be argued that participants may have experienced anger because they had personally been harmed by sexual objectification (i.e., interpersonal anger) and this experience may have promoted collective action. Therefore, Study 2 extended the findings of Study 1 by testing whether the relationship between sexual objectification and the willingness to engage in collective action was mediated by group-based, rather than interpersonal, anger.

Study 2

There were three main differences between Studies 1 and 2. First, in Study 2, we manipulated objectification by asking participants in the objectified (but not the control) condition to read a vignette in which they had been objectified by a man (see Teng et al. 2015). Second, we altered the covariates that were included in this study. Across the Pilot Study and Study 1, we demonstrated that a series of covariates could not account for the relationship between sexual objectification and the willingness to engage in collective action. Given this demonstration and to simplify the design, we did not include the majority of these covariates in Study 2. The only exception to this exclusion was the inclusion of self-objectification because this variable has been strongly implicated in such processes in previous research (Calogero 2013). Third, because Study 2 focused on the role of interpersonal and group-based anger in mediating the processes, we instead assessed emotion-based covariates. As we mentioned earlier, instances of discrimination may elicit feelings of shame (Matheson and Anisman 2009). Therefore, in Study 2 we tested whether group-based anger mediates these processes after accounting for interpersonal anger, interpersonal shame, and group-based shame.

Although we used an established sexual objectification manipulation in Study 2, we also included the interpersonal sexual objectification scale that was used in the Pilot Study and Study 1. This inclusion was because the manipulation and measure may assess different aspects of sexual objectification. For the manipulation, participants were asked to consider a single experience of sexual objectification. However, for the interpersonal sexual objectification scale participants were asked to consider numerous instance of sexual objectification that they have experienced over the last year. Being asked to consider numerous instances of sexual objectification is likely to highlight numerous instances when different members of an outgroup (i.e., men) have undertaken harmful actions. This process may result in participants being more likely to view sexual objectification as an intergroup issue than when considering the single instance of objectification in the manipulation. As such, the effects may be stronger for the measure rather than the manipulation. Because of this possibility, it was important to include both the established manipulation and measure of sexual objectification.

Method

Participants and Design

Participants were recruited through adverts on social media websites, online forums, and a course-credit system. The study was advertised to participants as looking at women’s thoughts, feelings, and actions toward objectification. To take part, participants had to be 18 years-old or older, female, and must not have an eating disorder or be likely to feel distressed when discussing objectification. Initially, 331 participants were initially recruited for this study. We removed 171 participants for not completing the study. We also removed one participant for being younger than 18 years-old. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 159 women. Participants were aged between 18 and 60 years (M = 26.47, SD = 8.39) and were most likely to either be students (n = 69, 43.40%) or working full-time (n = 51, 32.08%). Participants were more likely to be in a relationship (n = 95, 59.75%) than single (n = 60, 37.74%; 3 participants were divorced/separated and 1 participant selected other).

This between-participants study had two independent variables: the sexual objectification manipulation (control versus objectified) and the sexual objectification measure. The dependent variable was the willingness to engage in collective action. The mediating variables were interpersonal and group-based anger. Interpersonal and group-based shame and self-objectification were the covariates.

Materials and Procedure

After giving consent, participants were randomly allocated into the control or the objectified condition. Participants in both conditions were asked to imagine themselves interacting with a man. In the control condition participants were asked to imagine that they had shared their opinions on an interesting topic, whereas participants in the objectified condition were asked to imagine that the man had suggested he liked their body (for full manipulation, see Teng et al. 2015). All participants then completed a four-item manipulation check, adapted from Teng et al. (2015). These items were: “In the scenario, I felt more like a body than a real person”; “In the scenario, I felt my body and my personality were separate things”; “In the scenario, I was viewed more as an object than a human being”; and “It was only my body, not my personality, that caught this man’s attention.” All items were rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The average rating across all items was then calculated to create a measure in which higher scores indicate greater feelings of being objectified (α = .90).

The interpersonal emotions were then assessed. Participants were asked: “To what extent would the way the man treated you in this scenario make you feel [emotion word],” rated from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very much). The anger (α = .94) and shame (α = .90) emotion words were identical to Study 1. In order to disguise the nature of the manipulation, participants also rated four neutral (indifferent, apathetic, unconcerned, and relaxed; α = .56) and four positive emotions (happy, pleased, delighted, thrilled; α = .92). Although the indifference scale was not reliable, this was not an issue because these filler items were only being used to disguise the manipulation. To assess group-based emotions, participants were asked “As a woman, to what extent do you feel [emotion word] about the objectification of women in general,” rated from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very much). The anger (α = .94) and shame (α = .89) words were identical to Study 1. Participants then completed the collective action (α = .92), sexual objectification (α = .94), and self-objectification measures we used in Study 1. For each of these scales, the overall measure was calculated in the same way as in the Pilot Study and Study 1.

Statistical Analysis

We used a series of analyses to assess whether the (manipulated and measured) objectification variables predicted the willingness to engage in collective action and the mediating role of interpersonal and group-based anger. First, we performed an ANOVA to ensure that the objectification manipulation had a significant effect on the manipulation check and other variables. Moreover, we used a Chi-squared analysis to ensure that attrition rates were equivalent across both conditions (for a discussion, see Zhou and Fishbach 2016). Following these analyses, we assessed the relationship of objectification on the mediating variables (i.e., the emotions). For the objectification measure, this relationship was assessed using correlation analyses. If the manipulation was successful, we planned to assess the effect of this manipulation on the emotions through a series of ANOVAs. Finally, we assessed the significance of the indirect pathway from the sexual objectification variables to the willingness to engage in collective action via the emotions using the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013).

Results

Manipulation Check

Participants felt more objectified in the objectified than the control condition (see Table 5). Therefore, the manipulation was successful. Interestingly, the manipulation had a significant effect on the interpersonal emotions. By contrast, this manipulation did not have a significant effect on the other variables. Further analyses revealed that these findings needed to be interpreted with caution. This was because there was an association between condition and withdrawing from the study after the manipulation, χ2(1) = 26.05, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .29, caused by people being less likely to complete the study in the control (n = 60, 38.46%) than in the objectified condition (n = 99, 67.81%). This condition-dependent attrition violated the assumption of random assignment and suggested that the effect of the manipulation may be bias by condition-dependent attrition (Zhou and Fishbach 2016). Given this bias, we do not discuss the effect of this manipulation on the variables because these findings were questionable. Instead, our analyses focus on assessing the indirect effect of the sexual objectification measure on the willingness to engage in collective action via the interpersonal and group-based emotions. The effects of the manipulation were accounted for by including this variable into the analyses as a covariate.

Sexual Objectification, Emotions, and Collective Action

Correlation analysis demonstrated that the objectification, group-based anger, and the willingness to engage in collective action variables were positively associated, thereby providing preliminary support for the mediation model. These measures were also positively associated with all the other variables, except self-objectification and interpersonal happiness (see Table 6). Interpersonal happiness was negatively associated with the willingness to engage in collective action, but not associated with objectification or group-based anger. By contrast, self-objectification was not associated with any of the variables. Therefore, although the correlation analyses provided some support for the mediation model, it was important to ensure that any effects were not due to the covariates.

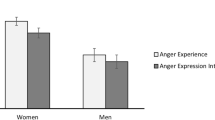

Next, we assessed the indirect effect of the sexual objectification measure on the willingness to engage in collective action via interpersonal and group-based anger. The mediation model suggested that the objectification measure predicted both interpersonal and group-based anger (see Fig. 2). Group-based (but not interpersonal) anger subsequently predicted the willingness to engage in collective action against sexual objectification. The significance of the indirect effects were tested by calculating the 95% confidence intervals, created using 5000 bootstrap resamples (Hayes 2013). The confidence intervals did not contain zero for the indirect effect via group-based anger (95% CI [.25, .64]). This analysis demonstrates a significant indirect effect from objectification to collective action via group-based anger. By contrast, the indirect effect via interpersonal anger was not significant (95% CI [−.02, .14]). Importantly, the indirect effect via group-based anger remained significant after controlling for self-objectification, interpersonal and group-based shame, interpersonal happiness, and the objectification manipulation (95% CI [.04, .35]). In this analysis, the indirect effect via interpersonal anger remained nonsignificant (95% CI [−.09, .05]). In this analysis, the objectification and group-based anger measures were the only variables to significantly predict collective action. These results suggest that group-based (but not interpersonal) anger mediated the relationship between sexual objectification and the willingness to engage in collective action.

In line with Study 1, we also tested the reverse mediation model. As such, we repeated the analyses to assess the extent to which sexual-objectification predicts group-based anger via collective action. The indirect pathway for this model was significant (95% CI [.22, .54]). This finding suggested a possible reverse mediation model (see Discussion).

Discussion

Study 2 replicated Study 1 by demonstrating that there was a significant indirect effect from the measured sexual objectification variable on willingness to engage in collective action via group-based anger. This mediation model suggests that sexual objectification promotes group-based anger and that this emotion subsequently promotes a willingness to engage in collective action. Although we replicated Study 1 in finding statistical evidence for a reverse mediation model, there was a stronger theoretical rationale for the hypothesised model than the reverse mediation model. Moreover, the inclusion of an appropriate sexual objectification manipulation check allowed us to effectively assess the influence of the sexual objectification manipulation. We found that this manipulation had a significant effect on the manipulation check and was thus successful. Importantly, we found that the manipulation predicted the interpersonal emotions, but not group-based anger or the willingness to engage in collective action.

In Study 1, we also found that the sexual objectification manipulation did not have a significant effect on the group-based emotions and the willingness to engage in collective action. However, it is difficult to draw conclusions from across the two studies because they have different manipulations. In addition, the outcome variables that were significantly influenced by the manipulation in Study 2 (i.e., manipulation check and interpersonal emotions) were not included in Study 1. As such, any comparisons are based on nonsignificant findings. Such comparisons are also problematic given that we also found the manipulation is Study 2 was biased by condition-dependent attrition (Zhou and Fishbach 2016). This condition-dependent attrition may have reflected the fact that the study was advertised as investigating women’s thoughts, feelings, and actions toward objectification, but that women in the control condition were presented with a vignette that did not contain sexual objectification. As such, this group may have been more inclined to leave the study.

Previous research has suggested that group-based shame is likely to result in the target withdrawing from social situations (Schmader and Lickel 2006). As such, it could be argued that group-based shame should deter collective action. However, we found that group-based shame did not predict the willingness to engage in collective action. This non-finding may have been due to the nature of the collective action. Indeed, research has suggested that shame promotes actions that improve the group’s image (Gausel and Leach 2011). However, the aim of the collective action assessed in our study was to tackle sexual objectification rather than improve the group’s image. Therefore, in our study, group-based shame may have been unlikely to deter collective action.

We found that attrition was higher in Study 2 than in Study 1, likely reflecting the recruitment strategies used in these studies. For Study 2, there was greater reliance on social media and online forms to obtain participants than in Study 1. Study 2’s recruitment strategy may have increased attrition rates. However, it is important to note that despite the difference in recruitment and attrition, the results of Study 2 replicate Study 1 in demonstrating the role of group-based anger in mediating the relationship between sexual objectification and willingness to engage in collective action. As such, this difference was unlikely to bias the findings.

General Discussion

Across three studies, we demonstrated that experiencing sexual objectification positively predicts willingness to engage in collective action. Moreover, Studies 1 and 2 both demonstrated that this relationship was mediated by group-based anger. Experiencing sexual objectification promotes feelings of group-based anger. This anger, in turn, motivated women to be willing to engage in collective action against the objectification of women. Importantly, these relationships remained after controlling for a variety of covariates, thereby demonstrating the robustness of the findings.

The present findings have important implications for the literature. Previous research has suggested that self-objectification may deter collective action against gender equality (Calogero 2013), but that women are willing to undertake action when they witness others being objectified either in person (Chaudoir and Quinn 2010) or by the media (Guizzo et al. 2017). Our study extended this previous research by demonstrating that personally experiencing sexual objectification promotes willingness to engage in collective action against the objectification of women. Moreover, recent research has suggested that experiencing interpersonal anger following sexual objectification motivates the target to undertake individualistic strategies to tackle the transgression (e.g., confronting the perpetrator; Shepherd 2019). The current studies extend this line of work by demonstrating that group-based emotions motivate the target to undertake collective strategies to tackle the transgression—specifically, by being willing to engage in collective action.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although our research has implications for the literature, it is important to discuss the limitations of our studies and potential future avenues for research. Given the correlational nature of our studies, further experimental research is needed to establish a causal relationship from sexual objectification to collective action via group-based anger. It could be argued that the relationship from sexual objectification to collective action may be due to other variables. Although we tested a series of covariates across the three studies, there may be still be some covariates that can account for this relationship. Moreover, given the correlational nature of this research, it is possible that the causal direction of the model could be reversed, as suggested by the reverse mediation analyses for Studies 1 and 2. There is a stronger theoretical rationale for sexual objectification to predict collective action than vice-versa. Moreover, other experimental studies have demonstrated that manipulating perceived discrimination and objectification promotes collective action via group-based anger (Guizzo et al. 2017; Van Zomeren et al. 2004). Therefore, it is likely that sexual objectification predicts collective action via group-based anger. However, additional experimental research is needed to further support these arguments.

Our study also could be criticised for assessing self-objectification using Noll and Fredrickson’s (1998) self-objectification questionnaire. Although this type of measure has been used in previous studies (e.g., Liss et al. 2011; Strelan et al. 2003), researchers have suggested numerous problems with this measure (Calogero 2011). Self-objectification was not a central variable in our studies. However, it would be beneficial for future research to use a more reliable measure of self-objectification in order to see how this relates to group-based anger and collective action.

Our study could also be criticised for assessing the willingness to engage in collective action rather than behaviour. Research has suggested that there is a gap between people’s intentions and their behaviour (Sheeran 2002). There is some evidence that the factors that predict collective action intentions also predict collective action behaviour (Van Zomeren et al. 2008). However, further research is needed to determine the role of sexual objectification and feelings of group-based anger towards this objectification on activist behaviour.

It is also important to determine the variables that may moderate these effects. For example, research has demonstrated that feminist self-identification promotes collective action (Nelson et al. 2008). Based on this linkage, it could be argued that women high in feminist self-identification should be more likely to experience group-based anger over instances of sexual objectification, increasing their likelihood of engaging in collective action. Moreover, research has demonstrated cross-cultural differences in objectification (Crawford et al. 2009; Loughnan et al. 2015). We did not measure culture in our research. Therefore, it is important for future research to empirically test the moderating role of feminist self-identification and culture on these processes.

Practice Implications

Given that women who engage in active responses to sexual objectification (e.g., reporting the perpetrator) are less likely to experience self-objectification (Fairchild and Rudman 2008) and that self-objectification is likely to have harmful effects on psychological well-being (Noll and Fredrickson 1998; Szymanski and Feltman 2014), it could be argued that it is important to encourage targets of sexual objectification to undertake an active response. Based in this reasoning, it has been suggested that interventions need to be developed that increase the likelihood of targets of sexual objectification to experience interpersonal anger in order to elicit these beneficial active responses (Shepherd 2019). However, one issue with this approach is that there is a cultural belief that it is not feminine to express anger (Citrin et al. 2004). Indeed, women who express anger are viewed negatively by others (Brescoll and Uhlmann 2008). The desire to avoid such negative evaluations makes women reluctant to express anger (Campbell and Muncer 1987; Evers et al. 2005; Fischer and Evers 2011). As such, it is important to find strategies that encourage targets of sexual objectification to experience and express feelings of anger.

Based on our research, we argue that intergroup processes may be applied to encourage targets of sexual objectification to experience anger and take action. Indeed, research has suggested that the belief that other women feel angry about an instance of gender discrimination has been found to promote collective action intentions through feelings of group-based anger (Leonard et al. 2011). The combination of this prior research with our studies suggests that encouraging women to share experiences of sexual objectification and their associated feelings of anger may increase the likelihood of other women experiencing group-based anger and thus their willingness to engage in collective action. This process highlights the importance of campaigns that encourage women to share experiences of sexual objectification (e.g., #MeToo Movement). By demonstrating the shared nature of such experiences among women these campaigns (a) emphasise that this is a group-based issue and (b) suggest it is important and legitimate for the target to share their experiences of and emotions toward sexual objectification. Therefore, such campaigns help to encourage collective action and tackle the inhibiting belief that women should not share feelings of anger. In turn, this demystification may increase the likelihood of women engaging in collective action against sexual objectification and promote social change.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our research assessed whether sexual objectification promotes women’s willingness to engage in collective action against the objectification of women. Across two studies, we found that sexual objectification was positively related to collective action and that this process was mediated by group-based anger. Importantly, this indirect effect remained significant after controlling for a series of covariates, including self-objectification. As such, we extend the existing objectification literature by suggesting that experiencing sexual objectification promotes collective action by women and the processes through which this occurs.

References

Brescoll, V. L., & Uhlmann, E. L. (2008). Can an angry woman get ahead? Status conferral, gender, and expression of emotion in the workplace. Psychological Science, 19, 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02079.x.

Brinkman, B. G., & Rickard, K. M. (2009). College students’ descriptions of everyday gender prejudice. Sex Roles, 61, 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9643-3.

Calogero, R. M. (2011). Operationalizing self-objectification: Assessment and related methodological issues. In R. M. Calogero, S. Tantleff-Dunn, & J. K. Thompson (Eds.), Self-objectification in women: Causes, consequences, and counteractions (pp. 23–49). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Calogero, R. M. (2013). Objects don’t object evidence that self-objectification disrupts women’s social activism. Psychological Science, 24, 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612452574.

Calogero, R. M., & Jost, J. T. (2011). Self-subjugation among women: Exposure to sexist ideology, self-objectification, and the protective function of the need to avoid closure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021864.

Calogero, R. M., Tylka, T. L., Donnelly, L. C., McGetrick, A., & Leger, A. M. (2017). Trappings of femininity: A test of the “beauty as currency” hypothesis in shaping college women’s gender activism. Body Image, 21, 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.02.008.

Campbell, A., & Muncer, S. (1987). Models of anger and aggression in the social talk of women and men. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 17, 489–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1987.tb00110.x.

Chaudoir, S. R., & Quinn, D. M. (2010). Bystander sexism in the intergroup context: The impact of cat-calls on women’s reactions towards men. Sex Roles, 62, 623–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9735-0.

Citrin, L. B., Roberts, T. A., & Fredrickson, B. A. (2004). Objectification theory and emotions: A feminist psychological perspective on gendered affect. In L. Z. Tiedens & C. W. Leach (Eds.), The social life of emotions (pp. 203–223). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Crawford, M., Lee, I. C., Portnoy, G., Gurung, A., Khati, D., Jha, P., … Regmi, A. C. (2009). Objectified body consciousness in a developing country: A comparison of mothers and daughters in the US and Nepal. Sex Roles, 60, 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9521-4

Doosje, B., Branscombe, N. R., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. (1998). Guilty by association: When one's group has a negative history. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 872–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.872.

Evers, C., Fischer, A. H., Rodriguez Mosquera, P. M., & Manstead, A. S. (2005). Anger and social appraisal: A" spicy" sex difference? Emotion, 5, 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.5.3.258.

Fairchild, K., & Rudman, L. A. (2008). Everyday stranger harassment and women’s objectification. Social Justice Research, 21, 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0073-0.

Fischer, A. H., & Evers, C. (2011). The social costs and benefits of anger as a function of gender and relationship context. Sex Roles, 65, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9956-x.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Frijda, N. H., Kuipers, P., & Ter Schure, E. (1989). Relations among emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.2.212.

Gausel, N., & Leach, C. W. (2011). Concern for self-image and social image in the management of moral failure: Rethinking shame. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.803.

Gordijn, E. H., Wigboldus, D., & Yzerbyt, V. (2001). Emotional consequences of categorizing victims of negative outgroup behavior as ingroup or outgroup. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 4, 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430201004004002.

Guizzo, F., Cadinu, M., Galdi, S., Maass, A., & Latrofa, M. (2017). Objecting to objectification: Women’s collective action against sexual objectification on television. Sex Roles, 77, 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0725-8.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Holland, E., Koval, P., Stratemeyer, M., Thomson, F., & Haslam, N. (2017). Sexual objectification in women's daily lives: A smartphone ecological momentary assessment study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56, 314–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12152.

Iyer, A., & Ryan, M. K. (2009). Why do men and women challenge gender discrimination in the workplace? The role of group status and in-group identification in predicting pathways to collective action. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 791–814. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01625.x.

Kozee, H. B., Tylka, T. L., Augustus-Horvath, C. L., & Denchik, A. (2007). Development and psychometric evaluation of the interpersonal sexual objectification scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00351.x.

Leach, C. W., Snider, N., & Iyer, A. (2002). “Spoiling the consciences of the fortunate”: The experience of relative advantage and support for social equality. In I. Walker & H. J. Smith (Eds.), Relative deprivation: Specification, development, and integration (pp. 136–163). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Leonard, D. J., Moons, W. G., Mackie, D. M., & Smith, E. R. (2011). “We’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it anymore”: Anger self-stereotyping and collective action. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430210373779.

Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., & Ramsey, L. R. (2011). Empowering or oppressing? Development and exploration of the enjoyment of Sexualization scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210386119.

Livingstone, A. G., Spears, R., Manstead, A. S., & Bruder, M. (2009). Illegitimacy and identity threat in (inter) action: Predicting intergroup orientations among minority group members. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48, 755–775. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466608X398591.

Loughnan, S., Fernandez-Campos, S., Vaes, J., Anjum, G., Aziz, M., Harada, C., … Tsuchiya, K. (2015). Exploring the role of culture in sexual objectification: A seven nations study. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 28, 125–152.

Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2009). Anger and shame elicited by discrimination: Moderating role of coping on action endorsements and salivary cortisol. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.522.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale: Development and validation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Nelson, J. A., Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., Hurt, M. M., Ramsey, L. R., Turner, D. L., … Haines, M. E. (2008). Identity in action: Predictors of feminist self-identification and collective action. Sex Roles, 58, 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9384-0

Noll, S. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00181.x.

Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., Zebel, S., & Fischer, A. H. (2007). The past and the pending: The antecedents and consequences of group-based anger in historically and currently disadvantaged groups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10, 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207071339.

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201272002.

Schmader, T., & Lickel, B. (2006). The approach and avoidance function of guilt and shame emotions: Comparing reactions to self-caused and other-caused wrongdoing. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9006-0.

Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.195.

Sheeran, P. (2002). Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792772143000003.

Shepherd, L. (2019). Responding to sexual objectification: The role of emotions in influencing willingness to undertake different types of action. Sex Roles, 80, 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0912-x.

Shepherd, L., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. (2013). ‘This will bring shame on our nation’: The role of anticipated group-based emotions on collective action. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.011.

Smith, E. R. (1993). Social identify and social emotions: Towards new conceptualizations of prejudice. In D. M. Mackie & D. Hamilton (Eds.), Affect, cognition and stereotyping: Interactive processes in group perception (pp. 297–315). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Smith, C. A., & Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Appraisal components, core relational themes, and the emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 7, 233–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939308409189.

Strelan, P., Mehaffey, S. J., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). Self-objectification and esteem in young women: The mediating role of reasons for exercise. Sex Roles, 48, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022300930307.

Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L., & Ferguson, M. J. (2001). Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00200.

Szymanski, D. M., & Feltman, C. E. (2014). Experiencing and coping with sexually objectifying treatment: Internalization and resilience. Sex Roles, 71, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0392-6.

Tausch, N., Becker, J. C., Spears, R., Christ, O., Saab, R., Singh, P., … Siddiqui, R. N. (2011). Explaining radical group behavior: Developing emotion and efficacy routes to normative and nonnormative collective action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022728.

Teng, F., Chen, Z., Poon, K. T., & Zhang, D. (2015). Sexual objectification pushes women away: The role of decreased likability. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2070.

Tylka, T. L., & Sabik, N. J. (2010). Integrating social comparison theory and self-esteem within objectification theory to predict women’s disordered eating. Sex Roles, 63, 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9785-3.

Van Zomeren, M., Spears, R., Fischer, A. H., & Leach, C. W. (2004). Put your money where your mouth is! Explaining collective action tendencies through group-based anger and group efficacy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 649–664. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.649.

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 504–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504.

Zhou, H., & Fishbach, A. (2016). The pitfall of experimenting on the web: How unattended selective attrition leads to surprising (yet false) research conclusions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advanced online publication, 111, 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000056.

Zurbriggen, E. L. (2013). Objectification, self-objectification, and societal change. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1, 188–215. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v1i1.94.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Sillence for her comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We would also like to thank Callum Watt and Chez Walbey for their assistance with data collection for Study 2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All studies were approved by the author’s Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was given by all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Shepherd, L., Evans, C. From Gaze to Outrage: The Role of Group-Based Anger in Mediating the Relationship between Sexual Objectification and Collective Action. Sex Roles 82, 277–292 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01054-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01054-8