Abstract

The present study examined the role of ambivalent sexist ideologies in the division of childcare responsibilities. We proposed maternal gatekeeping as a mediator through which hostile sexist attitudes toward men and women facilitate gendered division of childcare. A sample of 207 mothers with at least one child aged 6 years or younger completed extensive questionnaires. As hypothesized, the mother’s hostile sexist attitudes toward men and women were positively related to maternal gatekeeping tendencies. Gatekeeping, in turn, was related to the mother’s greater time investment in childcare and greater share of childcare tasks relative to the father. Finally, hostile sexist attitudes toward men and women had an indirect effect on the mothers’ hours of care and relative share of childcare tasks, mediated though maternal gatekeeping. The findings underscore the importance of investigating the mechanisms through which sexist ideologies are translated into daily behaviors that help maintain a gendered social structure. They may be utilized to inform parenting interventions aimed at increasing collaborative family work and fathers’ participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Ambivalent sexism theory (Glick and Fiske 1996, 1997, 2001) suggests that structural gender relations generate ambivalent sexist ideologies which, in turn, help to legitimize gender hierarchy and maintain traditional gender roles (Glick and Fiske 2001). These ideologies are adopted by men and women to varying degrees and affect the way in which they perceive and evaluate individuals of each gender. Indeed, a wealth of research has established the relationships between ambivalent sexist ideologies and a vast array of preferences and attitudes toward gendered behaviors and roles (e.g., Chen et al. 2009; Paynter and Leaper 2016; Russell and Trigg 2004). Nevertheless, to help maintain unequal social structures, ambivalent sexist ideologies should not just promote people’s endorsement of traditional gender norms and determine their judgments of gender-norms violators (Gaunt 2013a; Sakalli-Uğurlu 2010). Rather, sexist beliefs should affect people’s actual behaviors, including the work and family roles they assume. Yet surprisingly little research has addressed the mechanisms through which sexist beliefs are translated into individuals’ daily behavioral choices that maintain the social hierarchy (Montañés et al. 2012).

The present study aims to explore the implications of sexist attitudes for the division of childcare responsibilities. It proposes maternal gatekeeping as a link through which broad ambivalent gender ideologies may affect daily behavioral choices of individuals. Specifically, it advances the claim that maternal gatekeeping tendencies are shaped, in part, by women’s hostile sexist attitudes toward men and women and, in turn have consequences for their involvement in childcare. Maternal gatekeeping is therefore suggested as a mediator in the relationships between mothers’ sexist ideologies and the division of family roles.

Despite the societal change toward greater gender equality in the last decades (Altintas and Sullivan 2016; Bianchi and Milkie 2010) and gradual increases in fathers’ participation in housework and childcare (Hook and Wolfe 2012), cross-national studies show that gender inequalities in the division of family roles persist and mothers still assume main responsibility for childcare (Craig and Mullan 2011; Gracia and Esping-Andersen 2015; Neilson and Stanfors 2014). Such inequalities disadvantage women in the labor market (Gershuny 2004) and together, inequalities at home and at work preserve structural gender disparities. The current study focuses on the division of childcare responsibilities as a fundamental aspect of gender hierarchy in an attempt to reveal the role played by ambivalent sexist ideologies.

Ambivalent Sexism Theory

Ambivalent sexism theory (Glick and Fiske 1996, 1999, 2001) argues that the relationships between men and women are characterized by the coexistence of power differences and strong interdependence. This coexistence generates deeply ambivalent gender attitudes; whereas gender hierarchy and power differences result in hostility, heterosexual intimacy and interdependence result in benevolent attitudes (Glick and Fiske 1996, 2001).

Hostile sexism (HS) represents antipathy and resentment toward women who are viewed as challenging male power or rejecting conventional gender roles (e.g., “Most women fail to appreciate fully all that men do for them”; “Feminists are making unreasonable demands of men”). In contrast, benevolent sexism (BS) is a subjectively positive and affectionate attitude, which idealizes women in traditional roles and portrays them as pure but weak beings who ought to be adored and protected by men (e.g., “Women, compared to men, tend to have a superior moral sensibility”; “A good woman should be set on a pedestal by her man”) (Glick and Fiske 1996, 1997). Ambivalent sexism theory suggests that hostility and benevolence toward women form a complementary belief system that reinforces gender inequality. Benevolence is a positive reaction to women who conform to traditional roles, whereas hostility is a negative reaction to women who violate those roles (Glick et al. 2000). Therefore, both forms of sexism support a gender hierarchy that limits and disadvantages women who are seen as less competent and more suitable to caregiving roles.

The theory further posits that attitudes toward men are marked by a similar ambivalence (Glick and Fiske 1999, 2001). Hostility toward men (HM) reflects antagonism to men’s higher status and dominance (e.g. “A man who is sexually attracted to a woman typically has no morals about doing whatever it takes to get her in bed”) as well as their incompetence in family roles (e.g. “Men act like babies when they are sick”). Although expressing resentment of male power, hostile attitudes assume that male dominance on the one hand, and their incompetence in the home on the other, are both natural and inevitable (Glick et al. 2004). In contrast, benevolence toward men (BM) has a positive tone and admires men’s roles of protectors and providers (e.g., “Men are more willing to put themselves in danger to protect others”; “Every woman ought to have a man she adores”). Both hostile and benevolent attitudes toward men reinforce gender hierarchy by characterizing men as inherently powerful and aggressive while admiring their traditional roles (Glick and Fiske 1999, 2001).

Studies across many nations have shown that hostile and benevolent attitudes toward women are positively correlated with each other (Glick et al. 2000, 2004) as are hostile and benevolent attitudes toward men (Glick et al. 2004). All four types of sexist attitudes were found to be negatively associated with national indicators of gender equality (Glick et al. 2000, 2004). That is, the higher the average levels of sexist attitudes in a nation, the lower this nation’s scores on gender equality measures such as women’s representation in the economy and politics and gender equality in educational opportunities and life expectancy.

A wealth of research has further indicated that ambivalent sexism is related to a large variety of personal preferences and attitudes toward gender-related behaviors. For example, benevolent and hostile sexism were related to attitudes toward dating and sexual behavior (McCarty and Kelly 2015; Paynter and Leaper 2016; Zaikman and Marks 2014), tolerance of sexual harassment and rape (Durán et al. 2016; Russell and Trigg 2004), and attitudes toward women’s reproductive rights, pregnancy, and abortion (Hodson and MacInnis 2017; Huang et al. 2016; Sutton et al. 2011). Particularly important for our purposes, many findings indicate that sexist attitudes affect relationship and marriage norms and promote preferences for romantic partners who possess qualities congruent with traditional gender roles (Bermúdez et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2009; Thomae and Houston 2016). Specifically, women who endorsed benevolent sexism placed greater importance on partners’ status and resources, whereas men who endorsed hostile sexism placed greater importance on partners’ physical attractiveness (Sibley and Overall 2011; Travaglia et al. 2009). Such preferences may reinforce gender hierarchy by decreasing women’s motivation for direct access to resources (because they expect to be provided for by men) and increasing men’s motivation for resources (Sibley and Overall 2011).

Ambivalent Sexism, Work, and Family Roles

Ambivalent sexist attitudes reflect prescriptive ideologies about how men and women should behave and their appropriate roles in society (Chen et al. 2009). Such attitudes therefore not only lead men and women to seek romantic partners who conform to normative gender roles but also affect their judgments of individuals who violate these roles (Gaunt 2013a; Sakalli-Uğurlu 2010). For example, in the vocational domain it was found that hostile sexism predicted respondents’ negative judgments of women studying natural sciences (Sakalli-Uğurlu 2010), women managers (Sakalli-Uğurlu and Beydogan 2002), and female candidates for masculine-typed occupational roles (Masser and Abrams 2004). Likewise, benevolence toward men predicted more negative views of men studying social sciences (Sakalli-Uğurlu 2010).

Similar effects were found in the family domain (Gaunt 2013b). Specifically, hostile sexism predicted respondents’ negative judgments of a married mother who was the main breadwinner for her family, and benevolent attitudes toward men predicted respondents’ negative judgments of a primary caregiving father. In contrast, benevolent sexism predicted more positive views of a primary caregiving mother (Gaunt 2013b). Hence, ambivalent sexist attitudes generate positive reactions to individuals who conform to gendered family roles and negative reactions to individuals who challenge them.

Sexist ideologies therefore provide individuals with a set of prescriptive standards by which they judge the behaviors of others. Presumably, the same standards are being applied when people judge their own behaviors and make daily behavioral choices. Unfortunately, very little is known about the associations between sexist attitudes and actual behaviors. One study on a sample of Spanish female adolescents found that those who endorsed ambivalent sexist attitudes contributed more to traditionally feminine housework tasks (del Prado Silván-Ferrero and López 2007). Montañés et al. (2012) showed further that young women who adopted benevolent sexist beliefs had lower academic goals (e.g., getting good grades) and tended to focus more on traditional feminine goals (e.g., looking pretty, having a boyfriend, getting married) (Montañés et al. 2012). This, in turn, predicted their actual lower academic performance and therefore limited their future academic and career opportunities (Montañés et al. 2012). In this way, ambivalent sexist attitudes promote traditional gendered choices in the work and family domains, which in turn help maintain gender hierarchy. The current study examines such processes in a sample of British mothers and seeks to reveal how endorsement of sexist ideologies is related to women’s choices regarding the division of family roles.

Maternal Gatekeeping and Involvement in Childcare

To affect women’s decisions about the allocation of childcare responsibilities, broader sexist ideologies should first be translated into more specific attitudes toward motherhood, fatherhood, and the appropriate division of childcare responsibilities. Maternal gatekeeping is a set of beliefs and behaviors that may form this link between sexist ideologies and mothers’ daily behavioral choices.

Maternal gatekeeping is defined as a collection of beliefs and behaviors that ultimately inhibit a collaborative effort between mothers and fathers in family work (Allen and Hawkins 1999). These beliefs and behaviors restrict and exclude fathers from childcare and limit their opportunities to gain experience and develop the relevant skills (Allen and Hawkins 1999). One particularly widespread expression of maternal gatekeeping is the manager-helper pattern of relationships between mothers and fathers (Coltrane 1996). In this pattern, mothers act as managers who organize, plan, and schedule fathers’ involvement in childcare in order to maintain sole responsibility for the family work. Similarly, mothers may supervise the fathers, set higher standards, or criticize the quality of their housework and childcare (Thompson and Walker 1989).

Maternal gatekeeping is conceptualized as consisting of three related dimensions (Allen and Hawkins 1999). The standards and responsibilities dimension refers to the mother’s reluctance to relinquish responsibility by taking charge of tasks, setting strict standards or managing the father’s participation (e.g., “I frequently redo some household tasks that my husband has not done well”). The maternal identity confirmation dimension focuses more on the mother herself and refers to her desire for an external validation of the maternal role (e.g., “If visitors dropped in unexpectedly and my house was a mess, I would be embarrassed”). Finally, the differentiated family roles dimension is related to the mother’s gender ideologies (Gaunt 2009) and refers to her expectations for a gendered division of roles and distinct spheres for men and women (e.g., “For a lot of reasons, it’s harder for men than for women to do housework and childcare”). Together, these three dimensions reflect mothers’ endorsement of a gendered allocation of roles and their reluctance to share the control over housework and childcare with their husbands (Allen and Hawkins 1999).

Maternal gatekeeping has been shown to correlate with a more traditional division of family work (Allen and Hawkins 1999; Fagan and Barnett 2003; Gaunt 2008). Specifically, findings indicated that mothers’ gatekeeping tendencies were related to lower father involvement in childcare (Fagan and Barnett 2003), increased mother involvement in childcare (Gaunt 2008), and a greater difference between the time the mothers and the fathers invested in family work (Allen and Hawkins 1999).

Hostile Sexist Attitudes and Maternal Gatekeeping

Scholars explain maternal gatekeeping as a result of women’s fear of losing responsibility for family work because this responsibility serves as an important source of power, control, and self-esteem (Allen and Hawkins 1999). This fear should be understood within the context of women’s relative power and autonomy in the home and the lack of alternative sources of power elsewhere (Coltrane 1996). Because the job market continues to be segregated by gender, women’s job opportunities are often limited to low-paying, low-prestige or unfulfilling jobs (Allen and Hawkins 1999; Thompson and Walker 1989). Because the home remains the primary domain in which they enjoy power, authority and status, many women are reluctant to relinquish or share control over this domain. In line with this reasoning, it was found that gatekeeping tendencies were lower among women with higher educational qualifications, higher income, and greater subjective importance attached to their jobs (Gaunt 2008; Kulik and Tsoref 2010) whereas increased gatekeeping tendencies were found among women with lower self-esteem (Gaunt 2008).

If maternal gatekeeping serves women as a means to preserve power and control in the family domain, then women who endorse hostile gender attitudes should be more inclined to exhibit gatekeeping tendencies. This is because hostile sexist attitudes toward both men and women portray gender relationships as a power struggle; women seek to gain control over men (“Once a woman gets a man to commit to her, she usually tries to put him on a tight leash”) whereas men fight to preserve their power (“Men will always fight to have greater control in society than women”; “When men act to ‘help’ women, they are often trying to prove they are better than women”). Presumably, women who view gender relationships in terms of a competition over control are more likely to cherish their expertise and authority as caregivers and be reluctant to share childcare responsibilities in a way that could compromise the power and privilege attached to their role.

In addition, hostility toward men expresses resentment toward men’s incompetence in roles typically assumed by women while viewing it as inherent and natural (“Men would be lost in this world if women weren’t there to guide them”; “When it comes down to it, most men are really like children”). Women who perceive men as childish and deficient are less likely to trust them as caregivers and expect them to take an equal part in childcare. They are therefore more likely to exhibit maternal gatekeeping beliefs and behaviors.

Overview and Hypotheses

Ambivalent sexism theory (Glick and Fiske 1996, 2001) suggests that sexist ideologies serve to reinforce gender inequality. The present study aims to shed light on one of the routes from ambivalent sexist attitudes to unequal division of family responsibilities. In line with the reasoning we delineated, hostile sexist attitudes are expected to correlate positively with mothers’ gatekeeping beliefs and behaviors. Hostility toward men portrays men as incompetent in domestic roles, and therefore mothers who endorse such hostile attitudes are likely to view fathers as unsuitable for providing childcare. In addition, hostile attitudes toward both men and women stress the power struggle between the sexes and portray gender relationships as a competition over control. Mothers who endorse such views are likely to cherish their control over childcare responsibilities and be less willing to share it. Maternal gatekeeping, in turn, has been shown to correlate with higher maternal involvement and lower paternal involvement in childcare (Allen and Hawkins 1999; Fagan and Barnett 2003; Gaunt 2008). It is therefore suggested that maternal gatekeeping plays a mediating role in the relationships between ambivalent sexism and gendered division of childcare. That is, hostile sexist attitudes are expected to have an indirect effect on the time invested in childcare and the relative share of childcare tasks, mediated by maternal gatekeeping.

Three sets of hypotheses were assessed in the present study. First, sexist attitudes will be related to maternal gatekeeping (Hypothesis 1). Specifically, the more the mother endorses hostile sexist attitudes toward men (Hypothesis 1a) and women (Hypothesis 1b), the stronger her gatekeeping beliefs and behaviors will be. Second, maternal gatekeeping will be related to the division of childcare (Hypothesis 2). In particular, the stronger the mother’s gatekeeping beliefs and behaviors, the greater her time investment in childcare will be (Hypothesis 2a), the lower the father’s time investment in childcare will be (Hypothesis 2b), and the greater the mother’s share of childcare tasks relative to the father’s share will be (Hypothesis 2c). Third, maternal gatekeeping will mediate the relationships between hostile sexist attitudes and involvement in childcare (Hypothesis 3). That is, hostile sexist attitudes toward men and women will have indirect effects on the mother’s time investment in childcare (Hypothesis 3a), the father’s time investment in childcare (Hypothesis 3b), and the mother’s share of childcare tasks relative to the father’s share (Hypothesis 3c). Overall it is predicted that the more the mother endorses hostile sexist attitudes, the greater will be her maternal gatekeeping tendencies which will in turn result in a more traditional allocation of childcare responsibilities.

These hypotheses were tested on a convenience sample of British mothers with young children. Britain is considered a highly developed country with relatively low levels of gender inequality (ranked 16th of 188 countries on the UN gender inequality measure; United Nations Human Development Report 2016) and ambivalent sexist ideologies (Glick et al. 2000, 2004). Nevertheless, it is characterized by a dominant male-breadwinner/part-time female-caregiver ideological model, as reflected by a relatively large proportion of women in part-time jobs (Kanji 2011). Thus, the United Kingdom has both one of the highest employment rates in Europe for mothers of pre-school children and one of the lowest rates of maternal full-time employment (Kanji 2011). This gendered context therefore seems particularly suitable for examining the role played by sexist ideologies and maternal gatekeeping in the division of childcare responsibilities.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from a convenience sample of 207 British women as part of a larger research project on gender and families. Criteria for inclusion in the study were the following: Participants had at least one child aged 6 years-old or younger, they lived with the child’s father, and both parents were the child’s biological parents. The mothers’ ages ranged from 25 to 49 (M = 35, SD = 4.10). 173 (85%) participants identified as White British and an additional 20 (10%) were from other White backgrounds, which closely reflects the distribution in the UK general population (Office for National Statistics 2012). They represented a broad range of socioeconomic levels with an overrepresentation of educated women; 26 (13%) participants had high school education, 70 (34%) had first degree, and 89 (44%) had post-graduate qualifications. The mothers’ work hours ranged from 0 to 60 h per week (M = 29.60, SD = 13.27); 19 (9%) mothers in the sample did not work for pay, 79 (38%) worked up to 30 h per week, and 109 (53%) worked more than 30 h. The number of children per mother ranged from 1 to 4 (M = 1.55, SD = .69); 111 (55%) mothers had one child, 76 (37%) had two children, and 16 (8%) had three or four children. The target children’s age ranged from 0 to 6 years (M = 1.76, SD = 1.20), and 172 (83%) were 2 years-old or younger.

Procedure and Measures

Participants were recruited through advertisements in community centers, online forums, and playgroups across the United Kingdom. They were asked to fill in an online questionnaire on attitudes toward work and family. After receiving their consent, four screening questions were used to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Participants were asked if they had children, how old their youngest child was, if that was their biological child, and if they lived together with their child’s biological father. Participants who had more than one child were instructed to answer the questions with regard to the youngest child in their family. Completion of the questionnaire took approximately 20 min, and it included demographic questions about participants’ age, work hours, level of education and ethnic background as well as the number of children they had and the age and gender of each child. Participants were not compensated and all responses were anonymous. Measures were presented to participants in the order they are listed in the following.

Time Investment in Childcare

To assess involvement in childcare in terms of time investment, each participant was required to indicate (a) the amount of time (hours per week) during which she was the sole care provider when the child was awake and (b) the amount of time (hours per week) that the father was the sole care provider when the child was awake. The gap between mothers and fathers in their weekly hours of care was also calculated by subtracting the father’s weekly hours from those of the mother.

Involvement in Childcare Tasks

To assess involvement in childcare in terms of task performance, a “Who does what?” measure asked participants to indicate their involvement in 19 specific childcare tasks (adapted from Gaunt and Scott 2014). The 19 tasks were selected to reflect those types of involvement typical of both fathers (playing, disciplining) and mothers (feeding, packing child’s bag). Some tasks were designed to tap daily physical care activities (dressing, putting to bed), some were designed to reflect emotional care (helping with social/emotional problems), and some were selected to reflect responsibility for the child (choosing daycare/school, planning activities). Participants were asked: “In the division of labor between you and your spouse, which of you does each of these tasks?” Responses were indicated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost always my spouse) through 2 (my spouse more than myself), 3 (both of us equally), and 4 (myself more than my spouse) to 5 (almost always myself). Participants were also given the opportunity to rate 9 (not applicable to my child), which was treated as missing data. An average of the 19 task ratings was calculated to create a single measure of total involvement in childcare tasks. Higher scores on this measure reflected greater participation on the part of the mother relative to the father. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was .93.

To empirically distinguish major forms of involvement in childcare tasks, a principal-components factor analysis (with varimax rotation) was conducted on the 19 items. This analysis yielded a three-factor solution (with full results and a complete list of childcare tasks available in an online supplement). The first factor included seven items related to physical care for the child’s daily needs, such as feeding, dressing, and bathing. The second factor included five items that concerned providing socio-emotional care to the child, such as playing, helping with social or emotional problems, and taking on outings or social activities. The third factor consisted of seven items related to higher-order responsibility for the child, such as planning activities or scheduling social meetings, preparing the child’s bag before going out, and making arrangements for childcare. The variance explained by the three factors was 25.80, 21.00, and 19.76, respectively, and Cronbach’s alphas for the three factors were .82, .84, and .87, respectively. Mean scores for each of these forms of involvement in childcare tasks were obtained by averaging the participants’ scores for the items included in each factor, wherein higher scores indicated greater involvement. Similar involvement sub-dimensions have been identified in previous studies (e.g., Beitel and Parke 1998; Gaunt and Bassi 2012).

Ambivalent Sexism

Participants’ attitudes toward women were measured using the 22-item Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI; Glick and Fiske 1996). Participants responded to the items by using a 6-point scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly). The ASI consisted of two sub-scales: hostile sexism (HS) which assesses sexist antipathy toward women (e.g., “Feminists are seeking for women to have more power than men”) and benevolent sexism (BS) which assesses subjectively positive but patronizing attitudes toward women (e.g., “Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess”). Items were averaged to create composite HS and BS scores, wherein a higher score indicated more sexist attitudes. Cronbach’s alphas for these measures were .94 and .92, respectively.

Ambivalent Attitudes Toward Men

Participants’ attitudes toward men were measured using the 20-item Ambivalence toward Men Inventory (AMI; Glick and Fiske 1999). Participants responded to the items by using a 6-point scale labelled 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly). The AMI consisted of two sub-scales: hostility toward men (HM) which assesses resentment toward male dominance (e.g. “Men usually try to dominate conversations when talking to women”), and benevolence toward men (BM) which assesses appreciation of men as providers and protectors (e.g., “Men are more willing to take risks than women”). Items were averaged to create composite HM and BM scores, wherein a higher score reflected more sexist attitudes toward men. Cronbach’s alphas for these measures were .91 and .90, respectively.

Maternal Gatekeeping

Mothers’ tendency for gatekeeping was measured via Allen and Hawkins’ (1999) instrument. This measure consists of three separate dimensions. (a) Standards and responsibilities includes five items concerned with the extent to which mothers seek to maintain responsibility for family work by setting standards. Items in this scale were adapted to focus more closely on childcare. Sample items include: “My husband doesn't really know how to take care of our child (feeding, bathing etc.)... so it's just easier if I do these things” and “I have higher standards than my husband for providing childcare.” (b) Maternal identity confirmation is measured with four items concerned with the extent to which mothers associate their identity as mothers with observable competence in family work. Sample items include: “I know people make judgments about how good a wife/mother I am based on how well cared for my house and kids are” and “When my children look well-groomed in public, I feel extra proud of them.” (c) Differentiated family roles is assessed with two items concerned with mothers’ expectations and beliefs about men’s enjoyment and capabilities for doing family work: “Most women enjoy caring for their homes, and men just don’t like that stuff” and “For a lot of reasons, it's harder for men than for women to do housework and childcare.” Participants used a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me) to indicate the extent to which they identified with each statement. The respondent’s average score for each dimension was computed. Cronbach’s alphas for these dimensions were .80, .76, and .65 respectively. These reliabilities were very similar to those observed in previous studies (Allen and Hawkins 1999; Gaunt 2008). The average of all 11 items was also calculated to obtain a total gatekeeping score. A higher score on this measure reflected greater maternal gatekeeping tendencies. Cronbach’s alpha for this overall measure was .82.

Analytic Strategy

To test the first two sets of hypotheses, we first conducted Pearson correlations between ambivalent sexism, maternal gatekeeping, and measures of involvement in childcare. Next, we conducted a series of multiple regression analyses. All variables were assessed for possible multicollinearity using tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF). There were no signs of multicollinearity in any of the independent variables in the regression models (VIF = 1.83 and tolerance value = .54 for hostile sexism toward men and women; VIF values ranged from 1.20 to 1.39 and tolerance values ranged from .66 to .83 for the three maternal gatekeeping subscales). Potential multicollinearity was only detected among the control variables of benevolence toward men and women (VIF = 5.42, tolerance = .21). We therefore entered them in a separate stage using hierarchical regression models.

To test the third set of hypotheses regarding the mediation of maternal gatekeeping in the relationship between ambivalent sexism and the division of childcare, we followed the methods developed by Preacher and Hayes (Hayes 2013; Preacher and Hayes 2004) for evaluating conditional indirect effects using the bootstrap procedure. Bootstrap resampling of the data provides estimates for the model paths and a confidence interval of these estimates. All analyses were conducted using Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro with 1000 bootstrap samples and bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Replicating previous findings from diverse cultures (Glick et al. 2000, 2004), the inter-correlations among the hostile and benevolent sexism scores were moderate-to-strong (average r = .77) (see Table 1). As found previously, the correlation between benevolent attitudes toward men and women was particularly high (r = .87). Glick and Fiske (2001) explain that the two benevolence subscales are closely related because both emphasize the notion of complementary gender roles and male-female interdependence. Also consistent with previous studies (e.g., Gaunt 2008), the results showed that the three dimensions of maternal gatekeeping form distinct components of gatekeeping beliefs and behaviors as indicated by the low-to-moderate correlations among them (ranging from .29 to .52). Finally, the inter-correlations among involvement measures of task performance and hours of care were generally moderate, ranging from .34 to .58. This suggests that performance of tasks and investment of time reflect relatively independent aspects of involvement in childcare.

Ambivalent Sexism and Maternal Gatekeeping

The first set of hypotheses suggested that hostile sexist attitudes toward men (Hypothesis 1a) and women (Hypothesis 1b) would be positively related to gatekeeping beliefs and behaviors. To test these hypotheses, we followed the procedures recommended by Glick and Fiske (1996, 1999) and used partial correlations to examine the relationship of maternal gatekeeping with each hostility measure while controlling for benevolence and vice versa. Given the substantial correlations between hostile and benevolent sexism, partial correlations are recommended to provide purer measures of these variables (Glick and Fiske 1996, 1999). Table 1 presents the correlations between the four types of sexism and maternal gatekeeping. As hypothesized, both hostility toward women and hostility toward men were positively correlated with maternal gatekeeping, although the pattern of correlations seemed stronger for the latter. As Table 1 shows, hostility toward men had particularly high correlation with the standards and responsibilities dimension of gatekeeping (r = .32, p < .001), whereas none of the sexism subscales correlated with the identity confirmation dimension of gatekeeping.

To determine more specifically the contribution of each type of sexism to each dimension of maternal gatekeeping, a series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses was conducted (see Table 2). In each analysis, a variable pertaining to one dimension of gatekeeping was regressed on the set of two hostile sexism variables, followed by the set of two benevolent sexism variables as controls. Table 2 indicates that the regression equation of the total maternal gatekeeping score on the set of ambivalent sexist attitudes was significant and accounted for 16% of the variance. Hostile sexist attitudes toward men and women were both significant predictors in this regression analysis: The more the mother endorsed hostile sexist attitudes toward men and women, the less she was willing to share family work with the father.

Table 2 shows further that the regression equations of the standards and responsibilities and the differential family roles dimensions of gatekeeping on the set of ambivalent sexist attitudes were also significant and accounted for 19–27% of the variance in these dimensions of gatekeeping. Hostile sexism toward men was a strong and significant predictor in these regression analyses: The more the mother endorsed hostile sexist attitudes toward men, the more she sought to maintain responsibility for family work and believed in distinct gendered family roles. However, sexist attitudes did not predict the maternal identity confirmation dimension of gatekeeping. Overall, these results supported Hypothesis 1a regarding the role of hostility toward men in maternal gatekeeping, and provided somewhat weaker support for Hypothesis 1b regarding the role of hostile sexism toward women.

Maternal Gatekeeping and Involvement in Childcare

The second set of hypotheses suggested that maternal gatekeeping would be positively related to the mother’s time investment in childcare (Hypothesis 2a), negatively related to the father’s time investment in childcare (Hypothesis 2b), and positively related to the mother’s share of childcare tasks relative to the father’s share (Hypothesis 2c). Table 1 presents the correlations between maternal gatekeeping and the different measures of involvement in childcare. As shown in the table, the total maternal gatekeeping score was positively correlated with the mother’s hours of care, the mother-father gap in time investment, and with all forms of involvement in childcare tasks. The standards and responsibilities dimension negatively correlated with the father’s hours of care and showed particularly strong correlations with the division of childcare tasks. Thus, the more the mother sought to maintain responsibility for family work by setting standards, the more hours she provided childcare, the fewer hour the father provided childcare, and the greater was her share of all forms of childcare tasks relative to the father.

To determine the independent contribution of each maternal gatekeeping dimension to each form of involvement in childcare, a series of multiple regression analyses was performed. In each analysis, a variable pertaining to one form of involvement was regressed on the set of maternal gatekeeping dimensions. The regression results are presented in Table 3. As can be seen in the table, the regression equation of the mother’s hours of care on the set of maternal gatekeeping variables was significant overall and accounted for 4% of the variance in the mother’s time investment. However, none of the gatekeeping sub-dimensions was a significant predictor in this equation. The regression equation of the father’s hours of care on the set of maternal gatekeeping variables was not significant, but the standards and responsibilities dimension of maternal gatekeeping was a significant predictor in this equation. That is, the more the mother sought to maintain responsibility for family work by setting standards, the fewer were the weekly hours in which the father provided childcare. Finally, the regression equation of the gap between the mother’s and the father’s hours of childcare on the set of maternal gatekeeping variables was significant overall and accounted for 5% of the variance. The standards and responsibilities dimension was a significant predictor in this regression analysis: The more the mother sought to maintain responsibility for family work, the greater was the gap between the time she invested in childcare and the time invested by the father.

Table 3 shows further that the regression equations of involvement in childcare tasks (physical care, socio-emotional care, responsibility, and total involvement) on the set of maternal gatekeeping variables were significant overall and accounted for 12–18% of the variance in the division of childcare tasks. The standards and responsibilities dimension was a significant predictor in all four regression analyses: The more the mother sought to maintain responsibility for family work by setting standards, the greater was her share of childcare tasks relative to the father. The differential family roles dimension of gatekeeping was a significant predictor in the regression equations of physical care and total involvement in childcare tasks. Thus, the more the mother believed in distinct roles for men and women, the greater was her share of physical childcare tasks relative to the father. Overall, these results provided support for Hypotheses 2a–c, although the pattern of results regarding the division of childcare tasks (Hypothesis 2c) was stronger and more consistent than the findings regarding the mother’s and father’s hours of childcare (Hypotheses 2a–b).

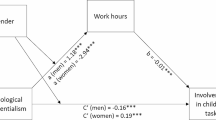

Ambivalent Sexism and the Division of Childcare

The third set of hypotheses suggested a mediation process in which maternal gatekeeping would mediate the relationships between hostile sexist attitudes and involvement in childcare. In particular, we hypothesized that hostile sexist attitudes toward men and women would have positive indirect effects on the mother’s time investment in childcare (Hypothesis 3a), negative indirect effects on the father’s time investment in childcare (Hypothesis 3b), and positive indirect effects on the mother’s share of childcare tasks relative to the father’s share (Hypothesis 3c). To assess these hypotheses, we evaluated a series of simple mediation models following the methods developed by Preacher and Hayes (2004). These analyses were conducted using the PROCESS program (model 4; Hayes 2013) with bias-corrected bootstrap estimates and 95% confidence intervals. To control for the positive relationships between hostile and benevolent attitudes, benevolence was entered into the model as a covariate when testing the effect of hostility, and hostility was entered into the model as a covariate when testing the effect of benevolence.

Table 4 summarizes the results of the mediation analyses. Consistent with Hypothesis 3a, these results indicate that hostility toward both men and women had indirect effects on the mother’s hours of care. These effects were mediated by maternal gatekeeping and were positive and significant, as indicated by bootstrap confidence intervals entirely above zero (95% CI [.07, 2.32] for hostility toward men and [.01, 2.47] for hostility toward women). Contrary to Hypothesis 3b, there were no significant indirect negative effects of ambivalent sexist attitudes on the father’s hours of care (95% CI [−1.55, .24] for hostility toward men and [−1.61, .13] for hostility toward women).

The results obtained for involvement in childcare tasks supported Hypothesis 3c and indicated that sexist attitudes had indirect effects on the division of childcare tasks (see Table 4). These effects were mediated by maternal gatekeeping and were all positive and significant, as indicated by bootstrap confidence intervals entirely above zero (95% CI [.01, .08] for hostility toward men and [.01, .09] for hostility toward women). Specifically, the mother’s gatekeeping tendencies mediated the positive relationships between her endorsement of ambivalent sexist attitudes and her relative share of childcare tasks. These mediated relationships were also found in two of the three forms of childcare tasks; ambivalent sexist attitudes had indirect effects on the division of socio-emotional care tasks (e.g., playing, taking on outings) (95% CI [.02, .10] for hostility toward men and [.02, .09] for hostility toward women) and responsibility for childcare (e.g., organizing, scheduling) (95% CI [.03, .10] for hostility toward men and [.01, .10] for hostility toward women) but not on physical care tasks (e.g., feeding, bathing) (95% CI [−.01, .06] for hostility toward men and [−.02, .08] for hostility toward women). All in all, these results provide support for the hypothesized mediation process in the effect of hostile sexist attitudes on the mother’s hour of care and her relative share of socio-emotional care and responsibility for childcare tasks, but not on the father’s hours of care and the division of physical care tasks.

Discussion

In the present study we sought to explore one possible mechanism through which sexist ideologies are translated into daily behaviors that help maintain a gendered social structure (Glick and Fiske 2001). We proposed maternal gatekeeping as a mediator, and we predicted that women’s hostile sexist attitudes toward men and toward women would be related to their gatekeeping tendencies, which, in turn, would be linked to the division of childcare responsibilities.

In line with our first set of hypotheses, the findings showed that hostile sexist ideologies played a role in mothers’ gatekeeping tendencies. Interestingly, hostile sexist attitudes toward men had stronger and more consistent relationships with gatekeeping than did hostile sexist attitudes toward women. Presumably, although hostile attitudes toward both women and men emphasize gender power struggles, only the latter also portray men as incompetent caregivers, which may play an important part in maternal gatekeeping. The second set of hypotheses regarding the role of gatekeeping in the division of childcare was also supported. Consistent with prior findings (Gaunt 2008), the standards and responsibilities dimension of maternal gatekeeping was the strongest predictor of the father’s time investment in childcare and the division of childcare tasks. Finally, mediation analyses confirmed our third set of hypotheses, showing that hostile sexist ideologies affect mothers’ hours of childcare and their share of childcare tasks through their gatekeeping beliefs and behaviors.

Different patterns of results appeared for the three dimensions of maternal gatekeeping. In particular, sexist attitudes were associated with the standards and responsibilities dimension, and, to a lesser degree, with the belief in distinct gender roles, but were unrelated to the identity confirmation dimension of maternal gatekeeping. This pattern of findings calls for a distinction between the more comparative dimensions of gatekeeping, which focus on the mother’s standards and performance in comparison to the father’s performance, and the maternal identity confirmation dimension, which focuses exclusively on the mother’s performance. This distinction is consistent with prior evidence which showed that these dimensions have different antecedents (Gaunt 2008), and it suggests that the standards and responsibility dimension is more inherent to the concept of gatekeeping than the identity confirmation dimension because the former better reflects an inhibition of the father’s involvement.

Our findings attest to the important distinction between different forms of childcare tasks (Lamb 1987). Although hostile sexist attitudes had positive indirect effects on the division of socio-emotional care (e.g. helping with social/emotional problems) and responsibility (e.g. planning activities), they did not affect the division of physical care tasks (e.g. feeding, bathing). This may indicate that sexism and gatekeeping are mainly expressed in the overall management and control over childcare rather than in the performance of daily routine tasks, as exemplified in the manager-helper pattern of relationships (Coltrane 1996). That is, hostile sexist mothers who view gender relations as a power struggle may be willing to delegate routine physical tasks to the father but reluctant to relinquish responsibility and control. Thus, to answer the question posed in the title, this pattern of findings suggests that although sexist mothers do not seem to change more diapers than non-sexist mothers, they do seem to perform a greater share of almost everything else.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although our study was the first known to explore the role of sexist ideologies in maternal gatekeeping and the division of childcare, there is much room for further developments and methodological improvements in this area. First, given the number of parameters tested, a larger sample would allow more confidence in drawing generalizations from the results. A certain amount of caution is therefore appropriate when considering our findings. In addition, our sample was characterized by an overrepresentation of well-educated working mothers. Previous findings indicated that education and paid work have negative associations with gatekeeping (Gaunt 2008; Kulik and Tsoref 2010), and it is therefore possible that the variance and levels of maternal gatekeeping in this study were relatively low. A more heterogeneous sample with a greater representation of less educated mothers may reveal stronger relationships of maternal gatekeeping with both sexism and involvement in childcare. In addition, the sample was restricted to heterosexual mothers of young children with resident fathers. Maternal gatekeeping may vary with older children or different relationship arrangements, and it may have even more pronounced implications for divorced or nonresident fathers.

Another methodological issue is the reliance on women’s self-reports as measures of both attitudes and behaviors. Self-reports may not be completely accurate and could result in shared-method variance and overestimation of the findings. For example, more sexist mothers may tend to over-estimate their share of childcare or underestimate the father’s share. Future research would benefit from including the fathers in the sample and measuring maternal gatekeeping and the division of childcare through direct observations in the home setting as well as both parents’ reports.

The inclusion of fathers in the sample could also help address a potential conceptual issue of maternal gatekeeping as a response to the father’s attitudes and behavior. Theoretically, sexist men may not be motivated to share childcare responsibilities which could lead mothers to exhibit gatekeeping tendencies. Maternal gatekeeping could therefore reflect either sexist mothers’ unwillingness to relinquish responsibility for childcare or sexist fathers’ reluctance to take this responsibility. Further research is needed to unpack the complex interactions between mothers’ and fathers’ sexist ideologies and their consequences for maternal gatekeeping and the division of childcare.

Practice Implications

Increased participation of fathers in childcare is beneficial to children’s social and emotional development (El Nokali et al. 2010; Flouri and Buchanan 2003) as well as to mothers’ and fathers’ psychological well-being and lower levels of stress (Milkie et al. 2002; Schindler 2010). Many intervention programs have therefore been developed to promote paternal involvement and positive family outcomes (e.g., Cowan et al. 2009; Panter-Brick et al. 2014; Rienks et al. 2011). Some of these programs focus specifically on the co-parenting relationship and are designed to reduce maternal gatekeeping and enhance collaboration between parents (McHale and Carter 2012; Pruett et al. 2017). The findings from our study have clear implications for such interventions as well as for practitioners who work with couples parenting young children. Our results highlight the role of hostile sexist attitudes in both maternal gatekeeping and involvement in childcare. In particular, they indicate that mothers’ endorsement of hostile sexist attitudes toward men and, to some degree, toward women promotes gendered allocation of roles and reduced levels of father involvement in childcare.

Mothers’ sexist ideologies should therefore receive more attention as part of the efforts to increase collaborative family relationships. Elements from existing programs aimed at confronting and reducing sexist ideologies (e.g., Zawadzki et al. 2014) can be adopted and incorporated into co-parenting interventions. These can help women become aware of their own sexist beliefs and their effect on their parenting and family life. For counsellors working with couples, our findings suggest that identifying and addressing hostile sexist beliefs should be an important step toward improving parental relationship dynamics. Increasing women’s awareness to such ideologies and their effect on daily behaviors and choices may help pave the way to greater equality in the home. It is likely that targeting men’s sexist ideologies can be similarly beneficial, however, the role of fathers’ ideologies is beyond the scope of the current study.

Conclusions

The findings of our study shed light on the indirect effect of hostile sexist ideologies on the division of childcare through mothers’ gatekeeping tendencies. They thus begin to unravel the mechanisms through which ambivalent sexist ideologies justify and reinforce gender hierarchy. Despite the crucial role such ideologies may play in societal processes (Glick and Fiske 2001), little research has so far examined their effect on individuals’ actual day-to-day behaviors (del Prado Silván-Ferrero and López 2007; Montañés et al. 2012). By illuminating one such path from ideology to behavior, the current study underscores the importance of exploring not only the role of sexist ideologies in various preferences and attitudes but also their consequences for actual behavioral choices. Further research into possible mediating mechanisms is needed to enhance our understanding of the ways in which ambivalent sexism promotes gendered social structures.

References

Allen, S. M., & Hawkins, A. J. (1999). Maternal gatekeeping: Mothers’ beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 199–212. https://doi.org/10.2307/353894.

Altintas, E., & Sullivan, O. (2016). Fifty years of change updated: Cross-national gender convergence in housework. Demographic Research, 35, 455–470. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.35.16.

Beitel, A. H., & Parke, R. D. (1998). Paternal involvement in infancy: The role of maternal and paternal attitudes. Journal of Family Psychology, 12, 268–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.12.2.268.

Bermúdez, J. M., Sharp, E. A., & Taniguchi, N. (2015). Tapping into the complexity: Ambivalent sexism, dating, and familial beliefs among young Hispanics. Journal of Family Issues, 36(10), 1274–1295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13506706.

Bianchi, S. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2010). Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00726.x.

Chen, Z., Fiske, S. T., & Lee, T. L. (2009). Ambivalent sexism and power-related gender-role ideology in marriage. Sex Roles, 60, 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9770-x.

Coltrane, S. (1996). Family man: Fatherhood, housework, and gender equity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., & Wong, J. J. (2009). Promoting fathers' engagement with children: Preventive interventions for low-income families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(3), 663–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00625.x.

Craig, L., & Mullan, K. (2011). How mothers and fathers share childcare: A cross-national time-use comparison. American Sociological Review, 76(6), 834–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411427673.

del Prado Silván-Ferrero, M., & López, A. B. (2007). Benevolent sexism toward men and women: Justification of the traditional system and conventional gender roles in Spain. Sex Roles, 57(7–8), 607–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9271-8.

Durán, M., Megías, J. L., & Moya, M. (2016). Male peer support to hostile sexist attitudes influences rape proclivity. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515624212.

El Nokali, N., Bachman, H. J., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2010). Parent involvement and children’s academic achievement and social development in elementary school. Child Development, 81, 988–1005.

Fagan, J., & Barnett, M. (2003). The relationship between maternal gatekeeping, paternal competence, mothers’ attitudes about the father role, and father involvement. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 1020–1043. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X03256397.

Flouri, E., & Buchanan, A. (2003). The role of father involvement in children's later mental health. Journal of Adolescence, 26(1), 63–78.

Gaunt, R. (2008). Maternal gatekeeping: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X07307851.

Gaunt, R. (2009). The role of mothers’ gender ideologies and essentialist perceptions in maternal gatekeeping. In J. H. Urlich & B. T. Cosell (Eds.), Handbook on gender roles: Conflicts, attitudes and behaviors (pp. 189–202). New York: Nova Science Publications.

Gaunt, R. (2013a). Breadwinning moms, caregiving dads: Double standard in social judgments of gender norm violators. Journal of Family Issues, 34(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12438686.

Gaunt, R. (2013b). Ambivalent sexism and perceptions of men and women who violate gendered family roles. Community, Work & Family, 16, 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2013.779231.

Gaunt, R., & Bassi, L. (2012). Modeling and compensatory processes underlying involvement in childcare among kibbutz-reared fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 823–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11428440.

Gaunt, R., & Scott, J. (2014). Parents’ involvement in childcare: Do parental and work identities matter? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314533484.

Gershuny, J. (2004). Time, through the life course, in the family. In J. Scott, J. Treas, & M. Richards (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to the sociology of families (pp. 158–173). Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/10022-3514/96/S3.00.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: Measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00104.x.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). The ambivalence toward men inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 519–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1999.tb00379.x.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). Ambivalent sexism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 115–188. https://doi.org/10065-2601/01535.00.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., … Lopez-Lopez, W. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 736–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.763.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., … Wells, R. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 713–728. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.713.

Gracia, P., & Esping-Andersen, G. (2015). Fathers’ child care time and mothers’ paid work: A cross-national study of Denmark, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Family Science, 6(1), 270–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424620.2015.1082336.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Hodson, G., & MacInnis, C. C. (2017). Can left-right differences in abortion support be explained by sexism? Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 118–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.044.

Hook, J. L., & Wolfe, C. M. (2012). New fathers? Residential fathers' time with children in four countries. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 415–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11425779.

Huang, Y., Davies, P. G., Sibley, C. G., & Osborne, D. (2016). Benevolent sexism, attitudes toward motherhood, and reproductive rights: A multi-study longitudinal examination of abortion attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(7), 970–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216649607.

Kanji, S. (2011). What keeps mothers in full-time employment? European Sociological Review, 27, 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq022.

Kulik, L., & Tsoref, H. (2010). The entrance to the maternal garden: Environmental and personal variables that explain maternal gatekeeping. Journal of Gender Studies, 19(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2010.494342.

Lamb, M. E. (1987). The father’s role: Cross-cultural perspectives. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Masser, B. M., & Abrams, D. (2004). Reinforcing the glass ceiling: The consequences of hostile sexism for female managerial candidates. Sex Roles, 51(9–10), 609–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-004-5470-8.

McCarty, M. K., & Kelly, J. R. (2015). Perceptions of dating behavior: The role of ambivalent sexism. Sex Roles, 72(5–6), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0460-6.

McHale, J., & Carter, D. (2012). Applications of focused coparenting consultation with unmarried and divorced families. Independent Practitioner, 32(3), 106–110.

Milkie, M. A., Bianchi, S. M., Mattingly, M. J., & Robinson, J. P. (2002). Gendered division of childrearing: Ideals, realities, and the relationship to parental well-being. Sex Roles, 47, 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020627602889.

Montañés, P., de Lemus, S., Bohner, G., Megías, J. L., Moya, M., & Garcia-Retamero, R. (2012). Intergenerational transmission of benevolent sexism from mothers to daughters and its relation to daughters’ academic performance and goals. Sex Roles, 66(7–8), 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0116-0.

Neilson, J., & Stanfors, M. (2014). It’s about time! Gender, parenthood, and household divisions of labor under different welfare regimes. Journal of Family Issues, 35, 1066–1088. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14522240.

Office for National Statistics, UK. (2012). Ethnicity and national identity in England and Wales 2011. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_290558.pdf.

Panter-Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., & Leckman, J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: Engaging fathers – recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(11), 1187–1212.

Paynter, A., & Leaper, C. (2016). Heterosexual dating double standards in undergraduate women and men. Sex Roles, 75, 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0628-8.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553.

Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (2017). Enhancing father involvement in low-income families: A couples group approach to preventive intervention. Child Development, 88(2), 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12744.

Rienks, S. L., Wadsworth, M. E., Markman, H. J., Einhorn, L., & Moran Etter, E. (2011). Father involvement in urban low-income fathers: Baseline associations and changes resulting from preventive intervention. Family Relations, 60, 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00642.x.

Russell, B. L., & Trigg, K. Y. (2004). Tolerance of sexual harassment: An examination of gender differences, ambivalent sexism, social dominance, and gender roles. Sex Roles, 50(7–8), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SERS.0000023075.32252.fd.

Sakalli-Uğurlu, N. (2010). Ambivalent sexism, gender, and major as predictors of Turkish college students’ attitudes toward women and men’s atypical educational choices. Sex Roles, 62(7–8), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9673-x.

Sakalli-Uğurlu, N., & Beydogan, B. (2002). Turkish college students' attitudes toward women managers: The effects of patriarchy, sexism, and gender differences. The Journal of Psychology, 136(6), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980209604825.

Schindler, H. S. (2010). The importance of parenting and financial contributions in promoting fathers' psychological health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 318–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00702.x.

Sibley, C. G., & Overall, N. C. (2011). A dual process motivational model of ambivalent sexism and gender differences in romantic partner preferences. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(2), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684311401838.

Sutton, R. M., Douglas, K. M., & McClellan, L. M. (2011). Benevolent sexism, perceived health risks, and the inclination to restrict pregnant women’s freedoms. Sex Roles, 65(7–8), 596–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9869-0.

Thomae, M., & Houston, D. M. (2016). The impact of gender ideologies on men's and women's desire for a traditional or non-traditional partner. Personality and Individual Differences, 95, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.026.

Thompson, L., & Walker, A. J. (1989). Gender in families: Women and men in marriage, work, and parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51, 845–871.

Travaglia, L. K., Overall, N. C., & Sibley, C. G. (2009). Benevolent and hostile sexism and preferences for romantic partners. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 599–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.015.

United Nations Human Development Report. (2016). Human development - Statistical annex. Table 5. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf.

Zaikman, Y., & Marks, M. J. (2014). Ambivalent sexism and the sexual double standard. Sex Roles, 71(9–10), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0417-1.

Zawadzki, M. J., Shields, S. A., Danube, C. L., & Swim, J. K. (2014). Reducing the endorsement of sexism using experiential learning the workshop activity for gender equity simulation (WAGES). Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313498573.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The study reported in this manuscript did not receive any external funding and there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The research was conducted in accordance with the American Psychological Association’s most recent code of ethics, as well as the University of Lincoln Regulations for Ethical Research. Ethical approval was granted from the Ethics Committee at the University of Lincoln.

Informed Consent

All of the participants were briefed and gave their informed consent before taking part in the study.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaunt, R., Pinho, M. Do Sexist Mothers Change More Diapers? Ambivalent Sexism, Maternal Gatekeeping, and the Division of Childcare. Sex Roles 79, 176–189 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0864-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0864-6