Abstract

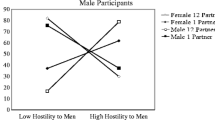

Theoretically, ambivalent sexism maintains gender hierarchy through benevolence toward conforming women but hostility toward nonconforming women. Men have shown ambivalent sexism to sex-typed vignettes describing “chaste” and “promiscuous” women (Sibley and Wilson 2004). This study of 117 Florida male and female undergraduate participants examined whether, benefiting more from gender hierarchy, men respond more extremely. If sexism supports gender hierarchy, social dominance also should moderate ambivalent sexism. Sexual self-schema (detailed, self-confident sexual information-processing) might moderate men’s and women's hostility. Supporting ambivalent sexism theory, women's hostility targeted the promiscuous character, but their benevolence targeted the chaste character, with men unexpectedly differentiating less. Social dominance enhanced Hostile Sexism and its differentiating the two female subtypes. Sexual self-schema moderated women’s but not men’s hostility.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson, B. L., & Cyranowski, J. M. (1994). Women’s sexual self schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1079–1100.

Anderson, B. L., Cyranowski, J. M., & Espindle, D. (1999). Men’s sexual self schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 645–661.

Carpenter, S., & Trentham, S. (2001). Should we take “gender” out of gender subtypes? The effects of gender, evaluative valence, and context on the organization of person subtypes. Sex Roles, 45, 455–480.

Cyranowski, J. M., & Anderson, B. L. (1998). Schemas, sexuality, and romantic attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1364–1379.

Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 33, (pp. 41–113)). New York: Academic.

Eckes, T. (2002). Paternalistic and envious gender stereotypes: Testing predictions from the stereotype content model. Sex Roles, 47, 99–114.

Fischer, A. R. (2006). Women's benevolent sexism as reaction to hostility. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 410–416.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social perception: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 77–83.

Glick, P. (2006). Ambivalent sexism, power distance, and gender inequality across cultures. In S. Guimond (Ed.), Social comparison and social psychology: Understanding cognition, intergroup relations, and culture (pp. 283–302). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). Ambivalent sexism. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 33, (pp. 115–188)). New York: Academic.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2003). Sexism. In S. Plous (Ed.), Understanding prejudice and discrimination (pp. 224–231). Boston: McGraw Hill.

Glick, P., Diebold, J., Bailey-Werner, B., & Zhu, L. (1997). The two faces of Adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes towards women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 1323–1334.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., et al. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775.

Haddock, G., & Zanna, M. P. (1994). Preferring “housewives” to “feminists”: Categorization and the favorability of attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18, 25–52.

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of System Justification Theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology, 25, 881–919.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Bertram, F. M. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741–763.

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2008). The social psychology of gender: How power and intimacy shape gender relations. New York: Guilford.

Sibley, C., & Wilson, M. (2004). Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes toward positive and negative sexual female subtypes. Sex Roles, 51, 687–696.

Sibley, C., Overall, N. C., & Duckitt, J. (2007a). When women become more hostiley sexist toward their gender: The system-justifying effect of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, 57, 743–754.

Sibley, C., Wilson, M. S., & Duckitt, J. (2007b). Antecedents of men’s hostile and benevolent sexism: The dual roles of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 160–172.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., van Laar, C., & Levin, S. (2004). Social dominance theory: Its agenda and method. Political Psychology, 25, 845–880.

Tavris, C., & Wade, C. (1984). The longest war: Sex differences in perspective (2nd ed.). San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fowers, A.F., Fowers, B.J. Social Dominance and Sexual Self-Schema as Moderators of Sexist Reactions to Female Subtypes. Sex Roles 62, 468–480 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9607-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9607-7