Abstract

Common causes of wrongful conviction include eyewitness misidentification, improper forensics, or false confessions (Garrett in Convicting the innocent: where criminal prosecutions go wrong, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2011; Innocence Canada, https://www.innocencecanada.com/causes-of-wrongful-convictions/); whilst none of these factors are in question in this paper, the notion put forward is that a more implicit factor is also at play; that is, the newspaper coverage of a criminal case during the lead up to trial. According to Felton Rosulek (Text Talk 28:529–550, 2008), “[…] linguistic choices conspire together […] and create a specific interpretation of reality”. Thus, this paper explores how the accused and the (alleged) criminal events pertaining to a high-profile case of the 1980s in New York are discursively framed in a range of press coverage across the USA and further afield. The corpus comprises newspaper articles reporting on the Central Park Jogger case, which resulted in the wrongful conviction and lost freedom of five innocent young men. Using corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis (CADS) (Partington and Marchi, in: Biber, Reppen (eds) The Cambridge handbook of English corpus linguistics, Cambridge University Press, 2015; Stubbs in Text and corpus analysis. Computer-assisted studies of language and culture. Blackwell, Oxford, 1996), the Transitivity patterns (Halliday and Matthiessen in Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar, Routledge, London, 2014) present in the press coverage are examined to gain insights into whether the portrayal of (1) the accused and (2) the victim at the centre of this case may have contributed to securing a wrongful conviction. Furthermore, this paper strives to (1) draw awareness to wrongful convictions more generally and (2) contribute to studies on Transitivity, which serve to highlight societal injustice and the power of printed news when determining the innocence or guilt of an accused individual. To acquire both quantitative and qualitative results, the UAM Corpus Tool (O’Donnell in UAM Corpus Tool, http://www.corpustool.com/) was also employed here.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Through recent exposure to different news sources, it seems there has been a sudden emergence or, perhaps more accurately put, a sudden recognition of wrongful convictions and, particularly, cases that have occurred across the United States. Numerous media and social media outlets, including national and international newspapers, Instagram, Twitter, Netflix, to name few, have been reporting on cases in which people have had years of their lives and freedom unjustly stolen from them as a result of human error and that, ultimately, contributes to generating a rather flawed justice system. Examples of wrongful conviction cases that surfaced in 2021 alone include Dontae Sharpe,Footnote 1 who spent 26 years in prison for a murder that he did not commit, Joyce Watkins,Footnote 2 who spent 27 years in prison for the murder of her great niece and has just last month been exonerated, Henry McCollum and half-brother Leon Brown,Footnote 3 who spent 31 years in prison for a rape and murder that neither committed and Kevin Strickland,Footnote 4 who spent 42 years in prison for a triple murder that he did not commit. Whilst only four cases are cited here, the list is far more extensive with evidence from the National Registry of ExonerationsFootnote 5 in the US suggesting that these are merely the tip of the iceberg.

Both local and national newspapers are particularly influential when it comes to swaying public opinion about real-world events and, especially, events concerned with the criminal justice system. As [52: 3] remarks, “very few of us, if any, are unaffected by media discourse”. Furthermore, readers readily assume that newspapers provide “faithful reports of events that happened out there in the real world beyond our immediate experience” [19: 10, 5: 430]. However, as Fowler asserts, “all news is always reported from some particular angle” and “[t]here are always different ways of saying the same thing […] they are not rando, accidental alternatives” [19: 4]. Thus, “[…] differences in expression carry ideological distinctions (and thus differences in representation)” [19: 4]. With that in mind, whilst newspapers are seen above to report on cases of wrongful conviction after the truth has come to light, it is equally important to acknowledge that any newspaper coverage, prior to a defendant’s trial, indeed has the potential to “have a detrimental effect on an accused person’s right to a fair trial by jury” [5: 428]. This idea has been put to the test in this paper, with a focus on one of the most high-profile criminal cases of wrongful conviction in history: the case of the Central Park Five.Footnote 6

In the late 1980s, the case of the Exonerated Five attracted attention on a global scale when five teenagers at the time, Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana and Korey Wise, found themselves accused of the rape and attempted murder of a young female jogger, Trisha Meilli, in Central Park, New York. All five teenagers were convicted of the charges and sentenced to several years in prison before eventually being exonerated in 2002 of any wrongdoing. According to the Exonerated Five themselves, the media had a very damaging effect on the outcome of their case, with Raymond Santana insisting in one of his Instagram posts that “the media made it very difficult for our case to get a fair trial. It is estimated that over 400 articles were written about us in a 2-week span calling us #Wolfpack #Wilding #Superpredator” (personal communication, 4th November 2021). In light of these remarks together with our understanding that, because of their role in construing social realities [19: 2], newspapers have a high degree of power and influence over the general population, it seems worthwhile exploring the notion that the representation of particular individuals in the printed press, in this case five black American teenagers, may have been a contributing factor to their wrongful conviction. As Chancellor [5: 428] maintains, “Pre-trial publicity frequently provides prejudicial information to the public, especially in high-profile or serious crimes, which limits the ability to find truly impartial jurors who have not been affected by the associated publicity”, an argument that lends itself nicely to the research questions proposed in this paper, which are as follows:

-

1.

Do the newspaper examined portray the Exonerated Five as guilty before the trial commences?

-

2.

Do the newspapers examined portray Trisha Meili as a “real” victim?

Before addressing the abovementioned questions in Sect. 5 of this article, we first delve into a description of the causes of wrongful convictions that have been identified thus far (see Sect. 2); Sect. 3 will provide a summary of some of the key research conducted to date examining the discursive portrayal across news outlets of serious criminal activities, such as rape and murder; Sect. 4 will detail the dataset, together with the theoretical framework applied in this study using the UAM Corpus tool [42] for analysis purposes; Sect. 5 will address each of the research questions and, lastly, Sect. 6 will offer some preliminary conclusions surrounding language within newspaper coverage as a contributing factor in wrongful conviction cases.

2 Causes of Wrongful Convictions

Due to the hard work of many legal experts around the world, more and more wrongful convictions are being overturned with innocent people exonerated of crimes that they never committed or that were never crimes to begin with. Furthermore, thanks to the endeavour by legal professionals to right those cases that slip through the net, we can begin to acquire insights into the issues that emerge at the original trial of the accused and that may prove a contributing factor to their erroneous guilty verdict, a loss of one’s freedom and, ultimately, a serious miscarriage of justice. Similarly, we can work towards preventing future miscarriages of justice, although to do so, it is paramount that the underlying causes of wrongful convictions are not only detected but also exposed. Thus, aside from their obvious relevance here, the latter is also justification for their inclusion in the current paper.

To date, a range of causes have been identified and discussed in depth by those working for any one of the numerous Innocence Projects worldwideFootnote 7 or within the broader legal arena itself. These causes include tunnel vision which, as Brants (5: 164) explains, refers to “the consequence of fixation on a certain suspect (bias) and the reason why this leads to a one-sided search for more incriminating evidence or to interpretations of evidence as incriminating (bias-confirmation), even in the face of facts that point in the opposite direction (belief perseverance) […] It is an inevitable element of human fallibility in criminal justice”. To add to the latter, other issues identified include professional misconduct [10], closely intertwined with the abovementioned cause, although as Brants [4: 165] maintains, one assumes “few policemen or prosecutors would intentionally ‘pin guilt’ on an innocent person […]”. The issue arises because “tunnel vision prevents us from seeing anything other than what is within our restricted range and, more importantly, leads us to believe there is nothing beyond what we can see” (ibid).

Although often serving to expose and correct a miscarriage of justice [9: 714–715], another contributing factor of wrongful convictions is faulty forensics, whereby so-called experts reach inaccurate conclusions regarding scientific evidence [32, 53, 55]; however, due to their status as “experts”, they are rarely doubted by the jury. Additional symptoms include jailhouse informant testimony, in which individuals who are already in prison are asked to testify against the accused in return for reduced jail time or an equally appealing form of compensation [39, 56] and systemic discrimination, whereby race and gender appears to impact the fate of an accused at trial [1].

Lastly, and in addition to the above cited causes, eyewitness misidentification, in which the victim or witness of a crime mistakenly identifies a suspect who is not in fact responsible [17, 46], or false confessions, in which suspects are coerced into telling police that they committed criminal activities that they did not [cf. 21 for details on the McCollum brothers’ wrongful conviction case; 27, 48], are thought to be the most common instigators of wrongful convictions. According to the Innocence Project, of all exoneration cases that have emerged so far and, subsequently, proved a client’s innocence with DNA testing, 70% involved people originally convicted on the basis of incorrect eyewitness identification. Similarly, in light of the known number of false confessions to date, it is estimated that of 2 million people incarcerated in the United States at present, with 10% most likely innocent of any wrongdoing, an average of 50,000 cases are likely to be convictions that result from false confessions. This cause is particularly pertinent here given that four of the now Exonerated Five were coerced into giving a false confession to police with the understanding that if they told police what they wanted to hear, the five teens would be allowed to go home. Of course, that did not occur and, instead, after alleging their involvement in the rape and attempted murder of Trisha Meili, all five boys were handed down prison sentences ranging from 5 to 12 years.

Although each of the causes outlined above can inevitably play a role in how likely a case will end up in a wrongful conviction, there are two things worth remarking upon. Firstly, all of the instigating factors described relate to one thing, which is the potential for human error. As Justice Blackman acknowledges, “human error is inevitable” [22]. Secondly and, although touched upon in other research [5, 23], another factor yet to appear among the more established list of wrongful conviction causes is how the press coverage of a case during the lead up to trial may also play a part. That is, the representation (i.e. the way in which language is used to denote certain groups, events and even non-animate entities) of the accused as well as the victim(s) involved may also nurture a wrongful conviction. This idea can, of course, extend to the courtroom and how each of the participants are discursively portrayed during trial by lawyers for each side of the case; however, for the purposes of this paper, the focus will remain on the language employed by the press during the lead up to the Exonerated Five’s original trial and the impact, if any, this may have had on the original outcome of their case.

3 Research on Reports of Criminal Activity in the Media

As Chancellor [5: 430] remarks, within criminology and sociology there has been a substantial amount of research looking into the media (i.e. newspapers, TV, radio, etc.) representation of criminal activity [12, 30, 41, 43]. Some of this research, in line with the topic of the current paper, has focussed on exoneration cases that have emerged and, in which, as Krajicek [31: 2] acknowledges, has led the media to receive recognition for their role in assisting with overturning a wrongful conviction case. That said, there seems to be far less research that examines whether “the media’s compliant coverage of any number of criminal prosecutions” has ultimately increased the likelihood of a wrongful conviction to begin with (ibid), bar perhaps a few exceptions, although rarely have these been explored within the scope of linguistics [49]. Instead, the focus has primarily been on examining concepts such as tunnel vision and other symptoms of wrongful conviction such as those outlined above. With that in mind, previous studies differ somewhat from the current paper, which not only aims to contribute further to the shortage of research in this area and take it beyond the scope of criminology and/or sociology, but also provide a rich linguistic analysis that may serve to further test the hypothesis put forward by criminology scholars. That is, they raise the question of whether the media, whilst rarely held accountable for their role in wrongful conviction cases, does in fact nurture a guilty verdict as a result of the language employed, regardless of what the truth may actually be.

To provide a brief overview of the research that has examined the news coverage of wrongful convictions, one notable study is that by Chancellor [5], who explores the role that pre-trial publicity plays in wrongful conviction cases. In her study designed to determine whether news reporting has any connection with public perception and the presumption of innocence in jury trials, specifically focussing on the cases of Guy Paul Morin and Robert Baltovich in Canada, Chancellor [5] uncovers three important findings: (i) the news reports were constructed to create a good vs an evil side, with victims of the crimes construed in such a way that would guarantee sympathy from the general public (e.g. as a young and innocent child in the case of Guy Paul Morin); (ii) the news stories were construed with the intention of inciting fear in the general public through, for instance, specifying a motive for the crime or, otherwise, associating the crime with criminal activity on a larger scale (e.g. linking Robert Baltovich’s alleged crime with high rates of sexual assault in the region); and (iii) the pre-trial publicity in these cases served to accentuate public outrage and, essentially cause exonerees Guy Paul Morin and Robert Baltovich to, more than likely, be denied a fair trial. From these findings and, particularly, the latter, Chancellor proposes ways in which courts can ensure that, in spite of pre-trial publicity, defendants are not presumed guilty before their case has even gone to trial. Among her recommendations is to (i) continually educate jurors throughout the trial by providing them with guidelines on fundamental legal principles such as “beyond a reasonable doubt”; (ii) to remind juror members not to consult news and online sources; and (iii) to perhaps distribute a questionnaire to jurors on completion of the trial to assess how they reached their verdict. Whilst these suggestions are certainly valid and would no doubt, if implemented, give the accused a better chance of a fair trial, what is perhaps most remarkable about these suggestions is that they, once again, infer that blame does not lie with the news outlets themselves; instead, those who make the law are the ones responsible for ensuring that juries do not have access and, in turn, allow the press to influence them. Thus, whilst society continues to look for a solution to address the impact of pre-trial publicity on defendants due to stand trial, one may argue that the same types of pre-trial publicity, for better or for worse, will inevitably continue to emerge and, likewise, the cycle of preconceived prejudicial trials.

Other research that merits attention, given the topic of this article, is by Statham [49], who examines the role of the media in jury trials. Although he makes no mention of wrongful conviction cases specifically, he does nonetheless assert that his aim is to establish the extent to which the interaction of media and legal discourses may impact upon the administration of justice [49: 2]. Furthermore, his research draws on systemic functional linguistics, as I do in this paper, with a focus on Transitivity and Appraisal in Chapters 4 and 5, specifically. On closer examination, Statham [49: 243] asserts that an analysis of newspaper articles reporting on criminal events clearly evidences the fact that the discourse plays a significant part in the construction of conceptualisations of crime for potential jurors” and, moreover, that a Transitivity analysis of his newspaper dataset indicates that “there can be no suggestion of objective neutrality in media language” [49: 245]. He also goes on to remark that “[c]oncepts of criminality and deviance are experienced by potential jurors in their role as media consumers” and, therefore, “the community values they bring to trial are not […] ‘common sense justice’ [18], but rather derive from their continual interaction with ideological media discourses [49: 286]. Although not resulting in a (wrongful) conviction, Statham [49: 247] makes nce to the Madeleine McCann case and the press coverage surrounding her parents as potential suspects in her disappearance whilst holidaying as a family in Portugal in May 2007. More specifically, he notes that “the level of condemnation expressed in an article would be an attractive commodity to a prosecuting attorney” and “covet an explicit opportunity to so negatively judge” the McCanns. With this in mind, had this high-profile case, described by The Daily Telegraph as the most heavily reported missing-person case in history, ever reached trial, it begs the question as to whether or not the McCanns would have faced a fair trial.

A final study that seems particularly pertinent to the current research paper is that by Clark [7], who examined newspaper articles from The Sun over a 3-month period between late 1986 and early 1987, those of which reported on more than 30 cases of male/female violence, sometimes of a sexual nature. Clark [7] set out to examine the Transitivity patterns across the newspaper discourse in question, in addition to the naming labels ascribed to particular participants who, in one way or another, were involved in the criminal events reported on by journalists. Among her findings, the accused was frequently labelled as a beast, a monster or a fiend, closely aligning with the type of press exposure received by the Exonerated Five when they had been detained and were under suspicion; that is, the Exonerated Five were commonly referred to as a wolfpack or as animals, serving not only to dramatise the story itself and, thus, make it more newsworthy [40], but simultaneously incite public fear and encourage the justification of harsh punishments for those alleged lawbreakers [57: 1]. That is, such descriptions inevitably conjure up an undesirable image in the minds of the general public, some of whom may have been called for jury service to try the very case for which they have had constant exposure to with countless negative associations concerning the accused.

To add to the latter, the Transitivity analysis in Clark’s [7] study suggests that the positions or, even, blatant absence of particular participants in certain clauses, be it in the headline or the main article itself, proved also somewhat revealing of who, if anyone, was held responsible for criminal activity. For instance, in one example the newspaper headline in Clark’s [7] corpus read as follows: Girl 7 murdered while mum drank at pub. One may first remark on the fact that through adopting the passive voice, no doubt in part so as to keep the headline short and punchy, The Sun nonetheless omits mention of a potential offender; as a result, the focus shifts from the criminal onto the victim. Furthermore, in this particular headline, thanks to the conjunction while placed in between two clauses, i.e. Girl 7 murdered and mum drank at pub, there is implicit blame assigned to this girl’s mother for not being at home with her 7-year-old daughter as society would expect. Therefore, we witness once again a shift of responsibility away from the actual perpetrator who committed murder and instead towards the mother with a suggestion of parent negligence.

Given that in the current paper a Transitivity analysis is also carried out on the dataset, a look at how both the five accused teens and the victim are positioned in the clause will be of much interest as it should also provide us with valuable insights into how the Exonerated Five were portrayed and, in turn, give us a sense of whether or not this could have been damaging to their impending trial at the time.

The latter now concludes a discussion of some research that, to date, has explored the portrayal of criminals, victims and criminal activities in newspaper and media discourse more widely, within and beyond the field of Linguistics. Section 4 will proceed with a brief explanation of the dataset retrieved for this study, together with the Transitivity framework that is used for analysis purposes.

4 Data and Method

4.1 Data

The dataset acquired for the present study consists of a broad set of newspaper articles that were published in 1989 following the rape and attempted murder of Trisha Meili in Central Park, New York. The newspaper articles were retrieved using LexisNexis, an online database that readily provides access for academic scholars to national and international press coverage of events around the world, in addition to courtroom judgements. In line with the aims of the current paper, however, only the former were retrieved.

The newspaper articles collected for this study were selected on the basis of two criteria: (i) the date of publication; and (ii) solely articles that reported on the Central Park Jogger case. The dates taken into consideration for the purposes of this paper range from April 20th 1989 (the day after the attack occurred) and 25th June 1990 (the day that the first trialFootnote 8 began). With this in mind, a total of 131 articles were retrieved from all available newspapers, which included The New York Times (USA), The Associated Press (USA), United Press International (USA), The Toronto Star (Canada), The Guardian (UK), The Sun Herald (USA), Sunday Tasmanian (Australia), Sunday Mail (UK), New York Daily News (USA), The Christian Science Monitor (USA), Petersburgh Times (USA, formerly called the Tampa Bay Times), The Globe and Mail (Canada), St Louis Post Dispatch (USA), The Mercury (Australia), The Independent (UK), USA Today (USA), CBS News (USA), Courier Mail (Australia) and The Canadian Press (Canada), resulting in a total word count of 70,417 tokens. The fact that one of the aims of this paper was not to compare newspapers but, rather, gain a general overview of how the Exonerated Five and those involved were reported on, it seemed worthwhile collecting as much coverage as possible, regardless of the newspaper source. That said, one must acknowledge that the results from this study may well have been different had there only been, for instance, an analysis of regional newspapers and not such a wide selection that, in this case, included local and global newspapers in an attempt to acquire a fuller and more reliable picture. Nonetheless, the prevalence of news articles in and around the USA, as well as in Canada, the UK, and Australia also offers a clear indication of how this case made headlines right across the globe and, thus, further justifies the scope of the corpus retrieved. In order to ensure that articles were only selected if reporting on the Central Park Jogger case and/or those involved, a series of search terms were used, to include: Central Park Five, Central Park jogger, rape, Anton McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise and Patricia Meili. Following this, proof reading of the articles was carried out in order to check that the articles discussed the case and/or those involved and to ensure that any duplicates were removed from the corpus before commencing the analysis.

4.2 Theoretical Framework and Method

For the purposes of analysing the abovementioned newspaper corpus and, in line with the aims of this paper, the Transitivity framework by Halliday and Matthiessen [25] is employed here. A Transitivity analysis is expected to shed light on the types of verbs (and nominalisations), henceforth referred to as process types, that emerge in the dataset and, more specifically, which participant roles are assigned to each of the Exonerated Five members and the victim of this case. In doing so, the findings are considered likely to reveal whether or not there is a more positive or negative portrayal of those involved as well as point towards accountability and whether the accused, in particular, are in fact presumed guilty before the case even reaches trial. The simple editorial decision to use an active clause with an explicit agentFootnote 9 as opposed to a passive clause in which the agent is removed, for instance, is ideologically driven [cf. 19: 4] and, therefore, a Transitivity analysis will serve to uncover such patterns and how this can colour the representation of particular participants.

According to Halliday and Webster [26: 25], the Transitivity system pertains to the experiential metafunction of language, which linguistically encodes and represents our experiences. Although not the only system of Transitivity proposed to date [15], Halliday and Matthiessen [25] put forward the most widely used in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), with their framework comprising 3 components: process types, participants and circumstances. Whilst the former two components are central to the system of Transitivity, the latter is defined as peripheral on the grounds that, unlike participant types which are process specific and an inherent part of the clause, circumstances can instead appear together with almost any, if not all process types. The focus in this paper is, specifically, on each of the process categories and subcategories, together with their pertinent participant roles, as detailed in Table 1Footnote 10 below.

The Transitivity framework [25] has been used for a vast amount of Critical Discourse Analysis research [3, 11, 34, 36, 38] with the aim of examining the way in which power and inequality radiates through a text [54] and, thus, reveal how certain individuals are portrayed in discourse. The latter is of particular relevance here given that this paper intends to determine how a group of alleged criminal perpetrators and a victim of rape is represented through the language choices made by journalists across the globe.

In order to cater for the analysis of an extensive amount of data, as well as reduce the potential for bias, corpus linguistics tools were employed during the analysis phase. AntConc [2], on the one hand, proved particularly useful for concordance searches containing, for instance, one of the search terms mentioned above (e.g. Korey Wise); meanwhile, the UAM Corpus Tool [42] was adopted for the manual analysis of Transitivity patterns, enabling not only a qualitative annotation of the dataset, but also retrieval of quantitative findings that could prove suggestive of statistical significance. These findings are now explored in Sect. 5 below.

5 Results and Discussion

This section will now address each of the research questions posed in this paper. To begin with, we examine how the Exonerated Five are represented in the newspaper discourse to determine the extent to which they are portrayed in a negative light and, even as guilty before having had their day in court. Subsequently, the discourse surrounding the victim, Trish Meilli, will also be examined to establish whether or not she appears to denote what some [6, 14, 33, 37, 55] have commonly referred to as “the ideal victim” or a “real victim”; the reason for doing so is that the construal of a real victim works not only to gain sympathy for the victim but simultaneously further reinforce the negative image constructed by the press of the alleged assailants. Thus, the question is whether this may have occurred in the case of Anton McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana and Korey Wise, five black teens accused of the rape and attempted murder of a white female jogger and, if it did, perhaps it is fair to conclude that the press played a role in this miscarriage of justice.

5.1 Do the Newspapers Examined Portray the Exonerated Five as Guilty Before the Trial Commences?

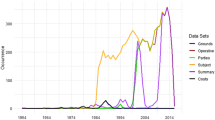

To address question 1 in this paper, it first seemed logical to gather a more general picture of the process types emerging across the dataset and, subsequently, explore in more detail the associations and specific participant roles assigned to the Exonerated Five in the press coverage during the build up to their original trial. Thus, Fig. 1 below illustrates the frequencies of each process type across the corpus, with material, relational and verbal categories proving notably more common by comparison to mental, existential and complex types.

Whilst useful as a point of departure, the above findings require further examination; thus, the material process clauses were extracted to give us further insights into just when they were being used with a member of the Exonerated Five. On closer inspection, a number of examples emerged in which the Exonerated Five as a group entity were placed in Actor position of a material clause, as evidenced in (1), (2) and (3) below.Footnote 11

-

(1)

“[…] Seven teenagers are now charged as members of the wolfpack who brutalized the woman during a night of’wilding’ […] (The Associated Press, 28/04/1989)

-

(2)

“[…] After their arrest, police said the suspects gave lengthy and harrowing details about the attack on the woman they caught […] – how they struck her with rocks and a length of pipe and how they punched and kicked her and took part in a sexual gang attack […] (New York Times, 11/06/1989)

-

(3)

“[…] Chief of Detectives Robert Colangelo said ''It's not a term that we in the police had heard before,'' he said. ''They just said, 'We were going ''wilding.''' In my mind at this point, it implies that they were going to go raise hell.'' […]” (United Press International, 22/04/1989)

As we can see in each of the above examples, taken from different newspapers and with different dates of publication prior to the original trial, the material processes employed in association with the Exonerated Five are particularly negative with violent connotations for the most part (i.e. brutalised, struck, punched, kicked, raise hell). Thus, here one may argue that we begin to witness how journalists, regardless of newspaper type, seem to guide public perception in a particular direction (cf. [50] for similar findings), that is, towards believing that these five teenagers are cold, calculated and dangerous individuals, who have just committed the most heinous of crimes imaginable. Examples (1), (2) and (3) also place the accused in Subject position of the clause, thereby emphasising their agency in the acts described. It is important to acknowledge, however, that the newspapers in our corpus do also employ a number of passive clauses, as in (4) and (5) below as well as nominalisations, as in (7). Both types of clause would seemingly serve to obscure the alleged perpetrators, but as the examples demonstrate, along with many others encountered in the corpus, the Exonerated Five are still cited, albeit in a more backgrounded fashion. That is, their agency is arguably reduced in some instances, but by no means is their alleged role in this crime concealed.

-

(4)

“[…] The prosecutor in the Central Park jogger case today detailed the horrors a young woman endured when she was beaten, gang-raped and left to die by a pack of youths during a night of wilding. […] (The Associated Press, 25/06/1990)

-

(5)

[…] “[…] she was jumped by the pack, bashed in the head with a pipe and dragged into a muddy ditch […]” (United Press International, 11/06/1990)

-

(6)

“[…] We in New York, and the rest of the country, are now caught up in a ritual of mass outrage and sadness, not to mention the stirrings of vengeance, over the savage beating and group rape of a 28-year-old woman jogger last week in Central Park by a herd of teenagers who crossed from prowling into pathology. […] (St Louis Post Dispatch, 30/04/1989)

To further reinforce the findings initially retrieved from the analysis of Transitivity processes in the dataset, it is worth remarking upon the naming strategies or, otherwise, metaphorical language that also appears in these news reports. As evident in each of the examples above, there are several references to animals (i.e. wolfpack, pack, herd), which have undeniable adverse connotations and, thus, serve to portray the Exonerated Five in a particularly negative light. When using the terms herd or pack, commonly defined as a group of wild animals who hunt their prey together, in association with the Exonerated Five, what occurs is that readers begin to envisage the accused as bearing a resemblance to a group of wild animals that hunt their prey which, in this case, is white female joggers. Therefore, in using a combination of clause types, whether denoting a higher or lesser degree of agency, together with metaphorical references to wild animals, it quickly becomes apparent just how damaging the press coverage most likely was for these innocent teenagers back in 1989 and 1990 in the lead up to their trial for rape and attempted murder.

On further observation of material processes, examples also emerged in which the Exonerated Five were instead the Goal of a clause, i.e. the entity impacted by the process, as illustrated in (7) and (8) below.

-

(7)

“[…] Richardson was charged with rape, attempted murder, assault, sodomy, robbery and riot. He was held without bail pending a May 10 hearing. […] (The Associated Press, 28/04/1989)

-

(8)

“[…] Defence lawyers, however, contend they are innocent and were rounded up by racially predjudiced police simply because the youths were black […]” (United Press International, 24/06/1990)

Whilst strictly speaking, Kevin Richardson, as well as the Exonerated Five as a group entity appear here as the affected participant in both clauses, example (7) unlike example (8) would still suggest Kevin Richardson is nothing short of a violent offender; moreover, one may argue that the use of thematic fronting here serves to place emphasis on the start of the sentence and, thus, on Kevin Richardson and his role in a spree of criminal behaviour as opposed to a portrayal of him as the one who is actually impacted by the process itself.

A final point worth making in relation to material processes and naming strategies, in light of the above examples, is in reference to the term wilding, which was coined as a new word that actually derived from the Central Park Jogger case itself. According to Welch et al. [57: 3], “the media searches for the originality, or novelty, of a story, and presents it as a hook expressed in the form of a word or phrase that grabs the public and commands their attention” and wilding is just “the type of invention that the media uses to hook the story of the Central Park Jogger case, as if the details of the brutal attack were not sufficient to drive the story” (ibid). Thus, through associating this new term with such a devastating level of violence and continually employing the word in newspaper coverage of this case, what inevitably occurs is that young, black and/or Latino men “are portrayed by the media and the criminal justice establishment as villains who prey on decent, hardworking people” [57: 13] and would, therefore, be best brought off the streets.

To now turn our attention to relational processes, the second most frequent category in the dataset, several examples emerge in which members of the Exonerated Five appear as a Carrier in the clause and are ascribed particularly negative attributes, as illustrated in examples (9) and (10) below.

-

(9)

“[…] ‘They were animals on a feeding frenzy’, a police officer told reporters. […]”. (The Guardian, 22/04/1989)

-

(10)

“[…] ‘Most of those involved, Mr Vachss says, are likely to be ‘emotional drifters’ but he says he doubts the level of violence would have been that high without the involvement of true sociopaths […]”. (The Christian Science Monitor, 05/05/1989)

As with the naming strategies described previously, examples (9) and (10) serve to further reinforce a negative image of the accused; furthermore, they demonstrate the potential for metaphorical language to incite public fear through the images conjured up in the minds of society.

To add to this, there were also examples that, if taken out of context, may appear at first sight to be assigning positive or simply ‘matter-of-fact’ attributes to the accused (e.g. to reference their racial or ethnic background), but, in fact, did just the opposite as a result of the surrounding co-text. Three such examples are provided below.

-

(11)

“[…] ‘They’re human beings who went berserk’, she said. ‘They had fantasies in their minds – of being like those on television, the ones who shoot people, who are powerful, in control, macho, aggressive, strong’ […]”. (The Associated Press, 27/04/1989)

-

(12)

“[…] The woman was beaten, stabbed and raped: a truly incomprehensible act perpetrated by a bunch of kids looking for a good time and – one of them reportedly said – white people to harm. The kids are black and Hispanic. […]”. (St Louis Post Dispatch, 13/05/1989)

-

(13)

“[…] Several came from broken homes and all lived in a neighbourhood surrounded by drugs and crime, but the youths accused of a savage gang rape of a Central Park jogger were unlikely attackers, by some accounts. […]”. (The Associated Press, 27/04/1989)

In example (11), the noun human beings or some of the adjectives (e.g. powerful, strong) arguably carry rather neutral or positive connotations; nonetheless, as a result of the surrounding co-text, the overall meaning ultimately leads to a negative representation of the five teens accused of this heinous crime. This is what is more commonly referred to in linguistics as semantic prosody, which as Partington [44: 68] explains, is “the spreading of connotational colouring beyond single word boundaries”. We witness a similar pattern in examples (12) and (13) whereby, in the former, there is a relational process to simply reference the colour of the defendants’ skin and their ethnic background. Meanwhile, in (13), the suggestion goes as far as to imply that the Exonerated Five are not, in all likelihood, the true perpetrators of this crime. However, the description of the same teens together with references to violence in such close proximity in both stretches of discourse means that neutral words such as black or Hispanic, for instance, suddenly become “imbued with undesirable meanings due to a transfer of meaning from their habitual context” [35: 157]. Moreover, this effect is multiplied if readers are consistently exposed to the same or similar reports and evaluations of a specific group, which seems to be the case given the wide scope of newspaper coverage on this case, with articles encountered in local, regional, national and international newspapers; that is, the general public over time become primed to foster particular views that the press (knowingly or not) encourage us to adopt [8].

It is also important to acknowledge that there were examples in the corpus in which the Exonerated Five are portrayed in a more positive light, as in (14) and (15) below. Nonetheless, these instances were largely overshadowed by the vast amount of negative press received by the defendants’ during the lead up to their trial.

-

(14)

“[…] All of them were regular school attenders; one of them played the tuba at Sunday School and another was doing well at a private religious school. […]”. (The Independent, 03/05/1989)

-

(15)

“[…] ‘I deal with kids in trouble; these kids were not trouble’, Mr Diamond said. […]”. (The Globe and Mail, 27/04/1989)

Before bringing this subsection to a close, we will briefly consider the verbal processes present in the dataset and, more specifically, identify who in particular was given a voice by the press and what impact this may have had on the outcome of this case. As evidenced in Fig. 2 below, the findings revealed that those in a position of authority appeared most commonly as Sayers of a verbal process, with examples such as (16), (17) and (18) to illustrate.

-

(16)

“[…] ‘When police found her’, Lederer said, ‘the victim was moving and groping and bleeding heavily. There was a blood-soaked t-shirt around her mouth, obstructing her breathing. Her pulse had dropped to 40. She was cold to the touch.’ […]”. (The Canadian Press, 25/06/1990)

-

(17)

“[…] ‘The rape was believed to be the group’s final assault of the night’, police said. […]”. (United Press International, 22/04/1989)

-

(18)

“[…] Without the statements, defense lawyers say the prosecution would have had no case […]”. (USA Today, 13/06/1990)

More specifically, the findings revealed that among those in a position of authority, the police and prosecution appeared three times more often as Sayers than the defence team that were working for the Exonerated Five. This finding alone is a bit of a give-away in that it offers us a good idea about whose side of the story was really being told in the newspaper coverage of this case, i.e. the accusers and not the accused or those championing their innocence.

To add to the abovementioned, it is important to acknowledge that the now Exonerated Five were also ascribed the role of Sayer on occasion, as evidenced in examples (19) and (20) below. Nonetheless, as we can see, when given a voice, it merely serves to further incriminate themselves in the rape and attempted murder of Trisha Meili.

-

(19)

“[…] They were bragging to each other about what they had told us and comparing notes […]”. (The Toronto Star, 24/04/1989)

-

(20)

“[…] Mr. Richardson told the police that 15-year-old Antron McCray, Mr. Santana and Mr. Lopez ripped the woman’s clothes off and gagged her before the four of them raped her. […]”. (The New York Times, 24/04/1989)

Thus, the overall conclusion reached in this subsection is that much of the press coverage in the build-up to the trial of the Central Park Jogger case most definitely worked against the accused. That is, in light of the incessant mention of their alleged violent actions together with references in which the defendants are compared to animals, as well as seen to incriminate themselves, it seems fair to say that, at least to a degree, the newspaper articles did indeed convey an assumption of five guilty defendants to the public, prior to trial even commencing.

5.2 Do the Newspapers Examined Portray Trisha Meili as a “Real” Victim?

According to Estrich [14], there are different categories of rape in terms of how the act itself, as well as the alleged perpetrator and the victim are viewed by the police, the prosecution (should the case make it as far as trial) and by the public. That is, Estrich [14] distinguishes between what she has termed simple rape and real rape, with the former understood to refer to those cases in which “a woman is forced to engage in sex with a date, an acquaintance, her boss or a man she met in a bar, when no weapon is involved and there is no overt evidence of physical injury” [13: 19]. Meanwhile, real rape, also termed stranger rape, is instead described as “an armed stranger jumping from the bushes and, in particular, a black stranger attacking a white woman” (ibid), with the latter considered far more likely to lead to an arrest and end in a subsequent conviction. Thus, we already start to see some parallels between Estrich’s [14] notion of real rape and the way in which the Central Park Jogger case played out, thereby leading us to consider the second research question: Does Trisha Meili constitute a victim of real rape? On exploring this further through an analysis of the Transitivity patterns employed in relation to the victim, two main findings came to light that merit attention in this paper. First and foremost, the victim emerges as an Actor, as in examples (21) and (22) below, in 20% of all material clauses, whilst appearing as Goal (i.e. the entity impacted by others or a happening), as in examples (23) and (24) in 32% of all material clauses.

-

(21)

“[…] She has returned to her Wall Street job and earned a promotion to vice president earlier this year. […]”. (United Press International, 10/06/1990)

-

(22)

“[…] ‘The Central Park jogger brutalized by a pack of roving teenagers conquered a fever Friday and continued to mend slowly’, doctors said. […]”. (The Associated Press, 06/05/1989)

-

(23)

“[…] a mob of youths on a “wilding” rampage who gang-raped, bludgeoned and left for dead a 29-year-old investment banker […]”. (United Press International, 11/06/1990)

-

(24)

“[…] The sensational case attracted world attention because of its brutality – the jogger’s face was smashed with stones and a metal pipe […]”. (USA Today, 13/06/1990)

As evidenced above, Patricia Meili is portrayed in a positive light and, in fact, aligns well with what Welch et al. [57: 3] explain about others preying on “decent, hardworking people”, Patricia Meili pertaining of course to the latter. Likewise, when seen as the Actor of a material clause, Meili is also given positive exposure with the press conveying the notion of ‘a miracle lady’, having had the capacity to recover from such a brutal and life-threatening attack. The relational process findings serve to further reinforce the aforementioned, with examples (25) and (26) reiterating the idea of Patricia Meili as a brave and incredibly strong individual.

-

(25)

“[…] The Central Park jogger, as she is known to the nation, remains unnamed but she has become a symbol of courage. […]”. (The Sunday Times, 10/06/1990)

-

(26)

“[…] as the days passed, the woman came through with a recovery described by doctors as ‘miraculous’ […]”. (United Press International, 21/06/1990)

Thus, given that the victim in this case is white and, at the time, was allegedly attacked by a group of black teenagers out of nowhere, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a case of real rape [14], in addition to her positive portrayal by newspapers worldwide, it seems reasonable to conclude that Patricia Meili does indeed reflect what some would constitute a “real victim”.

6 Conclusion

This research article has provided a contribution to existing studies in Forensic Linguistics, as well as those so far produced across Law and Criminology sectors in relation to wrongful convictions. To date, several symptoms of wrongful conviction have come to light, among which racial bias is a seemingly contributing factor in such cases [24, 47]. In fact, the latter is thought likely to have played a role in the demise of the now Exonerated Five back in 1990. That said, it seems reasonable to suggest that if race is a key cause of wrongful convictions, what we should do in response is look to address the discourse surrounding particular racial/ethnic groups in order to ensure that, as a society, we learn not to unfairly criminalise or condemn individuals based on their skin colour and, especially, before their case has even reached trial; that is, society needs to insist on upholding the idea of “innocent until proven otherwise”. This can arguably be achieved to some degree if we simply pay more attention to the language employed in the public arena and draw awareness to the impact it can have on the general public’s perception of certain groups in society, The current article attempts to do just this or, at least, lay a foundation for future research that examines newspaper language as a potential contributing factor of wrongful convictions.

To briefly summarise the transitivity findings retrieved from this study in particular, we witness tireless references by the press to Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana and Korey Wise as violent offenders, rapists, and animals. Moreover, their image was seemingly further damaged because of the accusation that they almost took the life of a “white, decent and hardworking” human being or, in the words of Senator Ben Tillman in 1907, “a creature in human form who has deflowered a white woman” will have committed “the blackest crime” [29: 57]. With that in mind, then, the overriding conclusion reached here is that journalists do seem to have influenced public perception towards these five young men, and to make matters worse, they may well have assisted the prosecution in this case with securing an erroneous conviction. That said, before this claim can be verified, additional research adopting, for instance, other SFL or related frameworks (e.g. Appraisal, metaphor, modality) is certainly needed.

Notes

See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-59270426 for the news report by the BBC.

See https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/14/us/woman-wrongfully-convicted-exonerated-trnd/index.html for the CNN news report.

See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57152860 for the news report by the BBC.

See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-59396598 for the news report by the BBC.

See https://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/about.aspx for a list of exonerees (1989–present day).

The Central Park Five from this point forward will, instead, be referred to as The Exonerated Five.

See, for instance, https://californiainnocenceproject.org/, https://www.innocencecanada.com/causes-of-wrongful-convictions/, https://www.law.northwestern.edu/legalclinic/wrongfulconvictions/issues/, https://law.uc.edu/real-world-learning/centers/ohio-innocence-project-at-cincinnati-law/educational-resources.html#factors for a list of causes.

There were two separate trials for the Central Park Five case and, thus, not all defendants were tried at the same time, which was allegedly tactical on the part of the prosecution.

The term Actor is used by Halliday and Matthiessen [25] and will be used henceforth in this paper.

The behavioural category has been removed and replaced with the possibility of annotating verbs or nominalisations as complex processes (i.e. those verbs or nominalisations that in specific contexts suggest two or more process categories are working simultaneously).

Throughout this paper, examples of process types are indicated in italics and underlined; meanwhile, examples of participant roles are highlighted in bold font.

References

Anderson, Andrea S. 2011. The silent injustice in wrongful convictions in Canada: Is race a factor in convicting the innocent? Unpublished Thesis. Toronto: York University.

Anthony, Lawrence. 2020. AntConc 3.5.9. Accessed 8 Aug 2021 from https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software/antconc/.

Bartley, L. 2018. Justice demands that you find this man not guilty: A Transitivity analysis of the closing arguments of a rape case that resulted in a wrongful conviction. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 28: 480–495.

Brants, Chrisje. 2013. Tunnel vision, belief perseverance and bias confirmation: Only human? In Wrongful convictions & miscarriages of justice: Causes and remedies in North American and European criminal justice systems, ed. C. Ronald Muff and Martin Killias, 161–192. London: Routledge.

Chancellor, Lauren. 2019. Public contempt and compassion: Media biases and their effect on juror impartiality and wrongful convictions. Manitoba Law Journal 42 (3): 427–444.

Christie, Nils. 1986. The ideal victim. In From crime policy to victim policy: Reorienting the justice system, ed. Ezzat A. Fattah, 17–30. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Clark, Kate. 1992. The linguistics of blame: Representations of women in The Sun’s reporting of crimes of sexual violence. In Language, text and context: Essays in stylistics, ed. Michael Toolan, 208–224. London: Routledge.

Coffin, Caroline Jane, and Kieran O’Halloran. 2006. The role of appraisal and corpora in detecting covert evaluation. Functions of Language 13 (1): 77–110.

Cole, Simon A. 2012. Forensic science and wrongful convictions: From exposer to contributor to corrector. New England Law Review 46: 711–736.

Covey, Russell. 2012. Police misconduct as a cause of wrongful convictions. Washington University Law Review 90 (4): 1133–1189.

Díaz, María Alcantud. 2012. The sisters did her every imaginable injury: Power and violence in Cinderella. International Journal of English Studies 12 (2): 59–71.

Dowler, Ken, Thomas Fleming, and Stephen L. Muzzatti. 2006. Constructing crime: Media, crime and popular culture. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 48 (6): 837–850.

Ehrlich, Susan. 2001. Representing rape: Language and sexual consent. London: Routledge.

Estrich, Susan. 1987. Real rape. How the legal system victimizes women who say no. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Fawcett, Robin. 1980. Cognitive linguistics and social interaction: Towards an integrated model of a systemic functional grammar and the other components of a communicating mind. Heidelberg: Juliu Groos & Exeter University.

Felton-Rosulek, Laura. 2008. Manipulative silence and social representation in the closing arguments of a child sexual abuse case. Text & Talk 28 (4): 529–550.

Findley, Keith A. 2016. Implementing the lessons from wrongful convictions: An empirical analysis of eyewitness identification reform strategies. Missouri Law Review 81 (2): 1–75.

Finkel, Norman J. 2000. Commonsense justice and jury instructions: Instructive and reciprocating connections. Psychology, Public Policy and Law 6: 591–620.

Fowler, Roger. 1991. Language in the news: Discourse and ideology in the press. London: Routledge.

Garrett, Brandon L. 2011. Convicting the innocent: Where criminal prosecutions go wrong. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Garrett, Brandon L. 2017. Actual innocence and wrongful convictions. In Reforming criminal justice: Pretrial and trial processes, vol. 3, ed. Erik Luna, 193–210. Academy for Justice: Arizona State University.

Garrett, Brandon L. 2020. Wrongful convictions. Annual Review of Criminology 3: 245–259.

Gould, Jon B., and Richard A. Leo. 2010. One hundred years later: Wrongful convictions after a century of research. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 100 (3): 825–868.

Gross, Samuel R. 2008. Convicting the innocent. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 4: 173–192.

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood., and Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin. Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. London: Routledge.

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood., and Jonathon J. Webster. 2014. Text linguistics: The how and why of meaning. Sheffield: Equinox.

Henderson, Kelsey S., and Lora M. Levett. 2018. Investigating predictors of true and false guilty pleas. Law and Human Behavior 42: 427–441.

Innocence Canada. Accessed 15 Mar 2021 from https://www.innocencecanada.com/causes-of-wrongful-convictions/.

Johnson, Matthew Barry. 2021. Wrongful conviction in sexual assault: Stranger rape, acquaintance rape, and intra-familial child sexual assaults. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kort-Butler, Lisa A., and Patrick Habecker. 2018. Framing and cultivating the story of crime: The effects of media use, victimization and social networks on attitudes about crime. Criminal Justice Review 42 (2): 127–146.

Krajicek, David J. 2014. The media’s role in wrongful convictions. How ‘mob journalism’ and media ‘tunnel vision’ turn journalists into tools of the prosecution: Three case studies. Centre on Media, Crime and Justice 1–18.

LaPorte, Gerald M. 2018. Wrongful convictions and DNA exonerations: Understanding the role of forensic science. National Institute of Justice 279: 1–16.

Lewis, Jerome A., James C. Hamilton, and Dean J. Elmore. 2019. Describing the ideal victim: A linguistic analysis of victim descriptions. Current Psychology 40: 4324–4332.

Li, Juan. 2011. Collision of language in news discourse: A functional-cognitive perspective on transitivity. Critical Discourse Studies 8 (3): 203–219.

Louw, Bill. 1993. Irony in the text or insincerity in the writer? The diagnostic potential of semantic prosodies. In Text and technology: In honour of John Sinclair, ed. Mona Baker, Gill Francis, and Elena Tognini-Bonelli, 157–175. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Machin, David, and Andrea Mayr. 2013. Personalising crime and crime-fighting in factual television. An analysis of social actors and transitivity in language and images. Critical Discourse Studies 10 (4): 356–372.

Moorti, Sujata. 2002. Color of rape: Gender and rape in television’s public spheres. New York: State University of New York Press.

Mwinlaaru, Isaac N., and Mark Nartey. 2021. “Free men we stand under the flag of our land”: A transitivity analysis of African anthems as discourses of resistance against colonialism. Critical Discourse Studies 19 (5): 556–572.

Natapoff, Alexandra. 2006. Beyond unreliable: How snitches contribute to wrongful convictions. Golden Gate University Law Review 37 (1): 107–129.

Nobles, Richard, and David Schiff. 2000. Understanding miscarriages of justice: Law, the media and the inevitability of crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Connell, Michael. 2002. The portrayal of crime in the media: Does it matter? In Criminal justice in Ireland, ed. Paul O’Mahony, 245–267. Dublin: IPA.

O’Donnell, Michael. 2020. UAM corpus tool. Accessed 19 Jan 2021 from http://www.corpustool.com/.

Oliver, Mary Beth. 2003. African American men as criminal and dangerous: Implications of media portrayals on the criminalization of African American men. Journal of African American Studies 7 (2): 3–18.

Partington, Alan. 1998. Patterns and meanings: Using corpora for English language research and teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Partington, Alan, and Anna Marchi. 2015. Using corpora in discourse analysis. In The Cambridge handbook of English corpus linguistics, ed. Douglas Biber and Randi Reppen, 216–234. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Risinger, D. Michael. 2007. Innocents convicted: An empirically justified factual wrongful conviction rate. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 97: 761–806.

Scheck, Barry, Jim Dwyer, and Peter Neufeld. 2001. Actual innocence: When justice goes wrong and how to make it right. New York: Signet.

Scherr, Kyle C., Allison D. Redlich, and Saul M. Kassin. 2020. Cumulative disadvantage: A psychological framework for understanding how innocence can lead to confession, wrongful conviction, and beyond. Perspectives on Psychological Science 15 (2): 1–31.

Statham, Simon. 2016. Redefining trial by media: Towards a critical-forensic linguistic interface. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Stratton, Greg. 2015. Transforming the central park jogger into the central park five: Shifting narratives of innocence and changing media discourse in the attack on the Central Park jogger, 1989–2014. Crime Media Culture 11 (3): 281–297.

Stubbs, Michael. 1996. Text and corpus analysis. Computer-assisted studies of language and culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

Talbot, Mary. 2007. Media discourse: Representation and interaction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Thompson, William C. 2009. Beyond bad apples: Analyzing the role of forensic science in wrongful convictions. Southwestern University Law Review 37: 971–994.

van Dijk, Teun. 2005. Contextual knowledge management in discourse production. A CDA perspective. In A new agenda in critical discourse analysis, ed. Ruth Wodak and Paul Chilton, 71–100. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

van Dijk, Jan. 2009. Free the victim: A critique of the western conception of victimhood. International Review of Victimology 16 (1): 1–33.

Warden, Rob. 2004. The snitch system: How snitch testimony sent randy Steidl and other innocent Americans to death row. In: Centre on wrongful convictions. Northwestern University School of Law. Accessed 10 Sep 2022 from https://www.aclu.org/other/snitch-system-how-snitch-testimony-sent-randy-steidl-and-other-innocent-americans-death-row.

Welch, Michael, Eric Price, and Nana Yankley. 2004. Youth violence and race in the media: The emergence of “wilding” as an invention of the press. Race, Gender and Class 11 (2): 1–21.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to my family for their never-wavering support, as well as Professor Maite Taboada, Professor Encarnación Hidalgo Tenorio and my colleague Lucas Chambers for guidance whilst working on aspects of this paper.

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Granada/CBUA. This article forms part of a larger project which has received funding from the European Commission under Grant Agreement No. 838444 (H2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie Programme).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartley, L.V. “The Jogger and the Wolfpack”: An Analysis of the TRANSITIVITY Patterns in the Global Media Coverage of the 1989 Central Park Five Case. Int J Semiot Law 37, 573–594 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-023-10026-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-023-10026-x