Abstract

Purpose The literature indicates that sexuality education provided in schools/colleges in the United Kingdom (UK) may not be appropriate for people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). There appears to be a lack of understanding of the subject regarding young people with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and a dual diagnosis (ASD co-occurring with ADHD). Research also suggests that compared to neurotypical peers, young people with ASD tend to receive less support on sexuality from their parents, who often feel that they lack the appropriate skills to help their children with some sex-related issues. Some young people with ASD and ADHD also report lacking an understanding of the social nuances of dating and intimacy, which is crucial for navigating romantic relationships. Design/methodology/approach This study explored sexuality education and romantic relationships in young people based on a semi-structured interview approach to the topic. Thematic Analysis (TA) was employed to analyze the data. Findings Six themes were developed from the participants’ narratives: Societal ideology about sexuality; Substandard school-based sexuality education; The role of adults in sexuality education; Pornography, as a very powerful alternative means of sexuality education; Young people and romance—a complicated world to navigate; Experience of abuse in the young neurodivergent population is a serious matter. Findings revealed that many neurodivergent and neurotypical young people received basic sex education in their schools/colleges and homes and encountered challenges navigating romantic relationships. Neurodivergent young people reported experiencing greater challenges related to their understanding of and building romantic relationships than their neurotypical peers. Originality/value To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first exploration of romantic relationships and sexuality education in neurotypical young people as well as three groups of neurodivergent young people (with ASD, ADHD, and ASD co-occurring with ADHD).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study sought to yield greater insights into romantic relationship experiences and sexuality education in autistic young people and young people with ADHD, as well as producing an initial understanding of the topic in young adults with ASD co-occurring with ADHD. The unique contributions to this important field were made from the perspectives of three groups of individuals: autistic young people, young people with ADHD, and young people with a dual diagnosis. The findings revealed that although the world of romance is challenging for many young adults, neurodivergent (ND) individuals tend to experience greater difficulties including a basic lack of knowledge related to gaining a romantic partner and abuse in their intimate relationships.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)Footnote 1 and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are two disorders that are classified under Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [1]. NDDs persist into adulthood [2, 3]. NDDs produce impairments at many levels of the individual’s functioning including personal, social, academic, and occupational. The range of developmental impairments of NDDs differs from very specific restrictions of learning or control of executive functions to comprehensive impairments in social skills or intelligence [4]. A meta-analysis [5], which included 96 studies of the prevalence of co-occurring mental health conditions in the autistic population, found that ADHD co-occurs with ASD in 28% of the autistic population. Hollingdale et al.’ [6] meta-analysis found that 21% of children and young adults with ASD also have ADHD. The co-occurrence of ASD with ADHD is associated with a greater likelihood of co-occurring psychiatric disorders such as behavioral disorder, anxiety disorder, mood disorder, and developmental disorder [7]. These conditions may affect young people’s capabilities to form social and romantic relationships [8, 9].

Romantic Relationships and Sexuality Education in Young People

Romantic relationships are vital aspects of one’s life [10,11,12] good quality relationships contribute to shaping one’s identity, promoting romantic relationships, as well as decreasing the levels of psychopathy in adulthood [10, 13]. Contrarily, low-quality relationships have been associated with alcohol or drug addictions, the experience of abusive romantic relationships, and academic failures [14,15,16]. Many young adults fluctuate between casual sexual romances [17,18,19]. This is because young individuals need to learn about one another at a much deeper level than just being in casual relationships and gain skills to resolve problems that occur within the relationships [20, 21]. Sustaining satisfying long-term, intimate relationships in adulthood requires a variety of skills including communication skills, maturity in managing conflicts, sustaining commitments, and comfort with one’s intimacy [22, 23]; hence sexuality education in this respect might be vital. The world of romance in neurotypical (NT) young adults appears quite challenging; studies across various countries highlight that many of them experience sexual and psychological violence in their pursuit of romantic relationships [24,25,26,27].

Typically, ND young adults including autistic young people [28, 29], and young people with ADHD [30, 31] have been found to encounter greater barriers to achieving satisfying romantic relationships than their NT peers. Some of the challenges experienced by autistic young adults include communication difficulties [32,33,34], a lack of awareness of how to establish romantic relationships [28, 35], and sensory difficulties [28, 32, 36]. Some autistic young people were reported to exhibit inappropriate behaviors such as touching another person without their consent [37] or providing ‘sexual services’ to others in exchange for money, without realizing the inappropriateness of doing it [38]. Young adults with ADHD were found to be promiscuous and more vulnerable to developing a sexually transmitted disease (STD) or becoming accidentally pregnant than their NT peers [30]. Autistic women [39,40,41,42] and women with ADHD [31, 43] were found to be more vulnerable to having negative sexual experiences (e.g., greater rates of intimate partner violence [IPV], perpetration, and victimization [43]) than their NT counterparts. Notably, autistic young people have been found to display much less understanding concerning sexuality than their non-autistic peers [29, 40, 44]. The lack of understanding of sexual concepts, misconceptions regarding intimacy issues, and being shamed for asking questions regarding sexuality, may contribute to relationship difficulties encountered by some young people with ADHD [45].

Understanding of romantic relationships in young adults with ASD co-occurring with ADHD appears to be absent in the current literature. Nonetheless, research [46] showed that children with ASD co-occurring with ADHD exhibit lower adaptive behaviors than those with a single condition of ASD or ADHD. Adaptive behaviors are essential to one’s functioning in society, as well as forming and maintaining romantic relationships [47]. They include communication and academic skills, interpersonal and social competence, and independent, daily living skills [48]. There is also a possibility that the presence of ADHD characteristics may further exacerbate the characteristics of ASD [49], which consequently may intensify the impairments in the executive functioning of individuals with a dual diagnosis. Individuals with a dual diagnosis display more severe impairments in executive and social processing including greater impairments in reading other people’s feelings and emotions, difficulties with communication, emotional and behavioral problems related to depression, and anxiety when compared to individuals with a single diagnosis of ASD or ADHD [50,51,52,53]. Therefore, individuals with a dual diagnosis might encounter even greater challenges with forming and maintaining their romantic relationships when compared to their counterparts with only one condition (ASD or ADHD).

The literature reviewed revealed a restricted amount of current knowledge regarding romantic relationship experiences and sexuality education in the autistic young population and the young population with ADHD [see also 54 for a systematic review of the literature]. Importantly, it also highlighted the gap in the existing understanding of the topic in the young population with ASD co-occurring with ADHD. Additionally, the current research [54] highlighted a limited qualitative exploration of the topic in autistic young adults and a lack of qualitative studies on the topic in young people with ADHD. This study adds its unique contribution to knowledge by qualitatively exploring the topic in ND and NT young adults. The inclusion of the NT group aims to help determine whether the experiences of ND young people in terms of their sexuality education and romantic relationships are typical of them or, generally, of all young people.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-four young people (12 NT and 22 ND) from the UKFootnote 2 between the ages of 18–25 years and five months took part in semi-structured interviews (See Table 1 for details on participants’ characteristics). The age of receiving the diagnosis of ASD was between three years and two months and 24 years and six months, and one participant with a dual diagnosis did not provide the age of their ASD diagnosis. The age of receiving the diagnosis of ADHD was between seven years and six months and 21 years and seven months; one participant did not provide this information.

Materials

Young adults were asked open-ended questions in the interviews. Examples of questions include: “How useful is/was the relationship and sex education you receive/received in terms of giving you the right tools and information for building and maintaining romantic relationships? What suggestions/recommendations can you give (e.g., providing technology-based sexuality education such as videos, applications, etc., tailoring sex education) for making these specific aspects more useful?”. The interview guide was designed based on the need and gaps in the current literature on the topic [e.g., 28, 55, 56].

Procedure

The interviews were conducted and recorded online via Microsoft Teams. Before the interview, participants read a participant information sheet and were given a consent form to sign. They also completed a short demographic questionnaire. Participants were given the choice of receiving the interview question guide in advance. This was especially useful for ND participants who often accepted that offer since becoming familiarized with the questions prior to the interview allowed them extra time to process the information, and also decreased their anxiety levels in relation to unfamiliar situations. On the day of the interview, before the recording, participants were given space to ask questions about the study. Participants were initially asked some generic questions to make them feel more comfortable (e.g., How’s your day been?). This was excluded from the analysis.

The first few interviews were transcribed manually, and then Microsoft Teams transcriber or Otter transcriber [57] were used to provide the transcription of the rest of the interviews. Neither of the automated transcribers was very precise in the transcriptions they provided; therefore, the first author had to check each of the transcriptions and make the appropriate corrections. Each participant was assigned specific letters (YP) and a number (1, 2, etc.). Additionally, any potential identifiers from all extracts from the interviews included in this study were anonymized or removed.

Analysis

The interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis (TA) [58, 59]. TA enables the analysis and interpretation of patterns across the dataset, which entails a systematic process of data coding to develop themes [58, 59]. TA may be applied to address a variety of qualitative research questions [59]. The flexibility that TA offers [59] made it the best-fitting approach to exploring romantic relationships and sexuality education in young individuals (ND and NT) from the perspectives of young adults. Braun and Clarke [56, 59] deem that this method of data analysis may provide an insightful interpretation of the outcomes. They [59] propose a six-phase technique to investigate results: (1) familiarisation with the data; (2) coding; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; 6) writing up. The first author followed the proposed six phases. The reflexive nature of the TA allowed the first author to move between the different phases in a spirit of interrogation [60] and the NVivo software, which was also used to conduct the analyses was a very helpful tool in this respect.

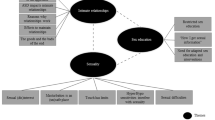

Findings

Six themes were generated from the dataset from young people’s interviews and some themes also have subthemes (see Table 2). Themes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are common to NT and ND young adults as the narratives provided by all groups contributed to their development. Theme 6 is common only to ND young adults as only the narratives provided by these groups contributed to its development.

Theme 1: Societal Ideology About Sexuality

Subtheme: Sexuality as a Taboo Topic

The narratives of young adults in this study centered on the construction of sexuality as “a very uncomfortable topic” (YP15, female with ADHD) that is not openly spoken about in our society. This lack of open conversations about sexuality may affect access to sexuality-related support since this taboo creates “a lot of stigma around sexual health clinics” (YP15, female with ADHD) contributing to the lack the awareness of the existence and usefulness of such places. This lack of open discussion around topics related to sexuality also influences certain conservative trends in societal thinking in terms of sexual behaviors.

Some participants reported being afraid of pursuing their romantic interests to avoid ‘slut-shaming’, which describes the act of criticizing a person for their actual or perceived promiscuous sexual acts [61]. Sexuality as a taboo topic in society may create further conservative trends of thinking. For example, being in a romantic relationship is regarded as “normal” (YP20, female with ADHD) without questioning why someone wants to be in a relationship. Consequently, some young adults might get involved in romantic relationships in which they feel uncomfortable since they believe they do “what [they are] supposed to do” (YP15, female with ADHD). Being single, on the other hand, is regarded as “not normal” (YP20, female with ADHD).

Subtheme: Influence of Religion on Attitudes Toward Sexuality

Some young people’s narratives also highlighted the existing Christian illiberal attitude toward sexuality. Christian schools do not provide teaching related to non-heteronormative sexuality since “it’s a sin in the eyes of God” (YP19, male with ADHD). This participant (YP19) described his school’s discriminative attitude toward non-heterosexuality as “disgusting”. He additionally reported: “It’s like you stay away from them [gay people] and then now it’s just like, they are just normal people, I don’t understand why I was told like that.” This indicates that some Christian schools, through their discriminative attitudes towards LGBTQ+, may teach young people prejudice and hostility. This consequently may add to the stigmatization that already exists among some groups of people around the globe against LBGTQ+ ideology. Religion indeed has a substantial impact on sexuality education since some young adults described that some students were withdrawn from sexuality classes due to their religious beliefs, which were against communicating knowledge regarding sexuality. Similarly, some participants, who were brought up in strict religious families, did not receive any sexuality education, instead, they “had to like go out there […] and figure it out […]” (YP16, female with ADHD) hence were left without any adequate guidance on these topics.

Subtheme: Construct of ‘hetero-activism’

Some participants clearly implied the construct of ‘hetero-activism’, which describes parental opposition to LGBTQ+ sexuality education [62], while describing some parents’ potential attitudes toward providing LGBTQ+ sexuality education to their children: “[…] it wouldn’t be appropriate to sort of dive into LGBT education because it might offend parents […]” (YP24, autistic male). The preceding comment underscores the importance of parental involvement in their children’s sexuality education, highlighting the need for school-parent collaboration. However, heteronormative ideologies remain pervasive in societal views, often dismissing homosexuality as unreal. One participant, YP23 (an autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man) shared that some people dismiss homosexuality as a phase: “[…] like slightly homophobic guy folks say that we are just phasing […]”. YP23 also emphasized that this dominant heteronormative attitude legitimizes bullying and contributes to discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals: “[…] just like, legitimated like a lot of bullying […]”. As a result, some young people feel compelled to hide their sexual orientation to gain societal acceptance: “I didn’t actually go after people that I liked [same sex people] I instead wanted to feel safe [accepted by society].” (YP27, autistic male).

Experiencing the stigma and prejudice toward non-heteronormative sexuality, which tends to be deemed undesirable by some societies and cultures [63], might also be “a very alienating experience” (YP7, NT nonbinary/female). This palpable stigmatization of LGBTQ+ sexuality across various institutions and in some young people’s homes may add to physical health and mental health problems that many LGBTQ + young individuals experience due to feeling segregated from the community [64].

Theme 2: Substandard School-Based Sexuality Education

Subtheme: It is Embarrassing

This cultural approach to sexuality as a taboo topic creates feelings of embarrassment when trying to discuss aspects related to sexuality. This was palpable during sexuality education lessons as reported by some young adults: “I think the students feel quite awkward in lessons when it’s a teacher that they know quite well who’s talking about sex […]” (YP28, autistic female). Not only might students find sexuality education awkward, but some teachers might also feel uncomfortable teaching this subject: “[…] my teachers were really uncomfortable about discussing it with me a lot of the time […]” (YP23, autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man). To cover the awkwardness of the lessons, some young people may take an unserious approach to them:

I think to everyone it’s more of a joke week [week of sex education] really isn’t it’s almost that’s how they deal with the at that age awkwardness of it is to see it as a joke and laugh it off. (YP18, male with ADHD)

Given that sexuality is a culturally taboo topic, young adults might not be used to hearing and conducting discussions about it. Therefore, when they start to learn about it in their schools/colleges, they might feel very uncomfortable, and to cope with this feeling, they may laugh. As a result, sexuality education may be treated in some schools/colleges as a laughing matter: “[…] nobody took it [the lessons] seriously, really.” (YP24, autistic male). This unserious approach to the subject and frequent laughing during the lessons may inevitably affect students’ concentration and subsequently reduce the learning outcomes. As highlighted by one participant (YP25, autistic male), there was nothing established by the teaching staff to help address this immature attitude displayed by students toward sexuality education. This may suggest that students’ preoccupation with humor during the lessons may serve a useful purpose for some teachers; distracted students do not pay much attention to the teacher, who might also feel embarrassed and unprepared to provide this type of teaching.

Subtheme: Superficial and Incomplete Teaching

Another factor that may suggest that sexuality education was not treated seriously in some schools/colleges was the limited number of lessons provided to students or, in the case of one participant, no teaching at all: “[…] we didn’t have it at all really… not in school or college, definitely not […]” (YP5, NT female). This participant (YP5, NT female) explained the reason for it, stating that normally the school “would bring people in to do, you know, the sex education classes, and then people just never came in so it never happened.”. This again highlights the unserious approach to the subject, despite being on the curriculum; teachers who were supposed to come to teach the subject did not arrive, however, no substitution was provided.

Similarly, the delivery of the material was offered in a very simplistic way (e.g., through PowerPoint presentations). Lessons were very often based on no discussions and there were no opportunities provided for students to ask questions. Additionally, the subjects were very limited and mostly related to the biological side of sexuality (e.g., reproduction). This may indicate that the sexuality education was inadequate in terms of offering young people knowledge that is important to understand their sexuality. Understanding one’s own sexuality may be essential in building and creating healthy romantic relationships. However, teaching related to romantic relationships was also non-existent or almost non-existent across many schools. This lack of teaching related to romantic relationships left many young adults having to learn about these topics through their own experience by trial and error. This existing lack of support in this context may contribute to negative experiences in young people’s relationships including different forms of abuse (sexual or psychological) and victimization [see e.g., 24].

Additionally, as one ND person (YP24, autistic male) indicated, for some young adults, especially ND, teachings related to very basic aspects (e.g., how to attract other people) about relationships might be crucial in order to give them an appropriate understanding of how to build a romantic relationship. Importantly, topics related to LGBTQ+ sexualities were also excluded: “[…] it was that definitely very much focused on like heterosexuality […]” (YP11, NT female). This lack of inclusive sexuality education may also be the outcome of conservative societal thinking as reported earlier.

Subtheme: Untrained Staff to Teach Sex Education

Notably, some young adults also felt that some of their teachers were ill-equipped to teach sexuality education: “[…] they probably got videos because they couldn’t do that, they didn’t know what to do with themselves, the teachers […] Like they didn’t know how to deliver the class themselves.” (YP17, male with ADHD). Some felt that some teachers presented having not very serious attitudes toward teaching sexuality as if they just have “a quota that we have to meet.” (YP22, female with ADHD). This again may highlight that sexuality education is not always given due attention, despite being included as an essential subject in the curriculum.

Subtheme: Sex Education Needs Improving

Given the inadequate sexuality education that many young people reported having received, they suggested several recommendations for the improvement of it. One of the aspects mentioned was that young people “are introduced to sex informally a lot sooner than it’s formerly brought up in school.” (YP12, NT female) and hence, it was recommended that sex education should be provided at an earlier age. Participants discussed the importance of providing inclusive sexuality education that would involve topics related to LGBTQ+ sexuality. Being asexual was also reported as something that should be incorporated into teaching and normalized. Further topics included romantic relationships, specifically aspects related to “recognizing when a relationship might be bad” (YP21, female with ADHD), “how to handle […] rejection” (YP14, male with ADHD), “how to form relationships” (YP24, autistic male), more in-depth contraception methods, sexual activities other than intercourse, and “how to find sex pleasurable” (YP27, autistic male).

Some participants additionally stressed that sexuality education would be enhanced by offering students more interactive lessons based on “opening it up to you know questions from us.” (YP25, autistic male) and giving young people the “opportunity to discuss things more” (YP28, autistic female). Some young adults also recommended introducing technology-based interactive sexuality education. Many of the aspects mentioned are already on the curriculum [64] and hence they should be discussed with young people during their lessons. The fact that this is not the experience of young adults may suggest an unserious approach to teaching this subject.

Another salient aspect that was highlighted was the importance of improving access to support services related to sexuality and romantic relationships for young people. This may imply that some young adults might lack knowledge about the existing support on sexuality and romantic relationships outside schools/colleges; therefore, signposting them to resources about it might be beneficial. Notably, teaching related to this aspect is included in the current curriculum [64], and again, therefore, should be covered. Adapting to all these changes would create more effective sex education for young people as concluded by one participant: “[this will] make it less stigmatized, less clinical, where you could feel more comfortable.” (YP10, NT female).

Theme 3: The Role of Adults in Sexuality Education

Subtheme: Limited Parent–Child Sex and Relationship-Related Discussions

Participants also described very basic topics related to sexuality that they discussed with parents, while some said that they did not discuss anything at all. Young adults provided different explanations for why they did not have a good quality sexuality education from their parents including the fact that parents were not “really a safe space” (YP12, NT female). One young person mentioned the aspect of cultural influences on sexuality-related communication with parents. She was of Indian origin (living in the UK), and from her narrative, it was apparent that sexuality is a subject that is not typically discussed within conservative Indian families in her experience. Additionally, another participant’s narrative highlighted that her parents were “very traditional people” (YP29, autistic female) and hence they did not discuss sexuality with her. This again implies that, traditionally, as a society, we do not discuss topics related to sexuality.

Participants who had sexuality-related communication with their parents reported covering topics such as masturbation, contraception, periods, and pregnancy. Some mentioned discussing topics related to romantic relationships, albeit at a basic level. Some others acknowledged that their parents tried to communicate with them about sexuality, however, they might have lacked the skills to do it effectively: “I think that might be that they didn’t feel qualified as well to talk about things like that […]” (YP26, autistic female). Additionally, some participants reported having found (potential) discussions related to sexuality with their parents as an awkward experience; despite this, they acknowledged their benefits.

One young woman provided examples of open sexuality communications that some of her friends had with their parents and the usefulness of those discussions in terms of helping them to manage challenging situations related to “more distressing sexual encounters or like instances of harassment and stuff like that.” (YP10, NT female). This indicates that parents play a crucial role in scaffolding the development of their children’s understanding of sexuality and romantic relationships. Notably, for these participants, conversations about sexuality with mothers were more open and easier to conduct, as opposed to with fathers. This may indicate that fathers may feel more embarrassed at conducting such talks with their children.

Subtheme: Parental Prejudice Against Children’s Non-heteronormative Orientation

Not only is it apparent that parent–child sexuality education is minimal, but some parents may also undervalue their children’s sexuality: “[…] they [parents] think I’m experimenting or something […] they don’t really think I’m valid just yet, which makes me down myself a lot.” (YP31, female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD). An autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man (YP23) reported that they could not discuss sexuality with their parents due to them being very judgemental and critical. Another participant admitted that although they are gay, they have never felt comfortable attempting to be in a gay relationship as this would have not been accepted by their family. In the case of this young person (YP9, NT gender-fluid/mainly female), the need to suppress their sexuality made them feel dismal and dubious that they would ever feel confident enough to pursue their true sexual and romantic interests. The narratives imply that children value their parents’ opinions regarding their own sexuality while parental lack of acceptance of their sexual orientation negatively influences their mental health.

Subtheme: Ways of Improving Sex-Related Discussions with Parents

As a consequence of the very limited sex-related communication that young adults had with their caregivers, some offered their views on improving this communication. Participants mentioned that it would be useful if their parents spoke to them about consent, emergency contraception, being aware of and how to recognize what harassment, sexual assault, and rape are, and STDs, and how to engage in safe sex. Other recommendations included “[…] signs of abuse like not just physical abuse […] emotional abuse and touching upon grooming as well.” (YP33, female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD). One participant additionally added that “[…] it could be quite beneficial, especially if you know the parents […] kind of like [not] forcing the young persons […] making them feel comfortable […]” (YP6, NT female). This might suggest that young people may find sexuality-related discussions with their parents beneficial, however, if the discussion is approached in an inappropriate way, it may then be counterproductive.

Subtheme: The Role of Professionals in Sexuality Education

Given the inadequate support that young adults received from their parents, as well as in their schools, some of them suggested that it would be beneficial if professional health services were also involved in providing sexuality education or would offer some type of support for young people in this respect. One participant (YP22, female with ADHD) stated that “[…] the school would just ignore it.” when describing available support for young adults related to some aspects of relationships in her school. This could imply that some schools may not have adequate resources including teachers’ training to support students with some sexual and romantic relationship challenges. Support provided by professionals might, therefore, be more effective.

Some participants spoke about the potential benefits of allocating school-based professional services for young people including a safe environment and “being readily available to people” (YP2, NT female). This indicates that young adults would like to have easy access to support; given that they spend many hours at school, creating such spaces on the school’s premises might be beneficial. Some participants shared their experiences of accessing school/college-based professional support and although their narratives demonstrated that such support may not always be adequate and very useful, many felt that professionals are generally more helpful in this respect than teachers. For example, one LGBTQ+ participant (YP23, autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man), reported that professionals made them feel “[…] a lot safer, like, you’re not going to be outed […]” than teachers. One of the reasons for this might be that: “teachers […] might not have the training, the doctors or nurses or external will have […]” (YP34, male with ASD co-occurring with ADHD). One neurodivergent young individual, however, stressed the lack of professional support in terms of romantic relationships that would be specific to the neurodivergent community: “It’s hard to find a neurodivergent friendly therapist, especially with relationships […]” (YP31, female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD). This may indicate a pressing need to enable adequate support for ND individuals in this respect.

Theme 4: Pornography as a Very Powerful Alternative Means of Sexuality Education

Due to the inadequate sexuality education many young people receive both in their schools/colleges and their homes, many feel the need to search for the information elsewhere. Pornography was reported as being one of the most powerful, alternative means of sexuality education for young adults:

I think you can’t talk or think about sex education in young people without talking about pornography because right, it’s just so important […] children learn so much more from pornography than they do from any kind of institution or schools […] (YP18, male with ADHD)

Given that pornographic materials are easily accessible on the internet, young adults may use them as a source of information, which they may pursue by themselves without any unnecessary feelings of embarrassment, which often accompanies the school’s sexuality education. Some participants, however, acknowledged “very unrealistic expectations and things” (YP3, NT male), as well as emphasizing the potential danger of learning about sexuality and romantic relationships from pornographic materials: “It’s tarnishing people’s minds […] I’ve been victim to it […]” (YP14, male with ADHD). Since pornography is “so widely accessible for people to watch” (YP5, NT female), some may use this resource from a very young age: “You know he [brother] told me what, like pornography was when I was like 7.” (YP11, male with ADHD).

Some narratives also clearly highlighted a lack of education about pornography both in educational institutions and in young people’s homes, despite its common use amongst the young population. One young male reported that although his mum could have been aware that he and his brothers were watching pornography, she never discussed this subject with them since: “[…] perhaps she didn’t know what to say […]” (YP18, male with ADHD). This may suggest that some parents, despite being aware that their children may watch pornography, might feel ill-equipped to conduct discussions with them related to this topic.

Theme 5: Young People and Romance—A Complicated World to Navigate

The result of a lack of adequate sexuality education for young adults was also evident in participants’ narratives regarding their romantic relationships since many of them reported having experienced various challenges while navigating the world of romance. Some participants’ accounts of those experiences have drawn attention to the common casual approach to romantic relationships adopted by some young people: “I’ve dated people in the past and I’ve never been official with anyone.” (YP3, NT male). This casual attitude to romance appears to be a dominant trend amongst young individuals as highlighted by one woman: “I can see in these days, like, casual relationships are very common and kind of are like it feels almost as if they’re like they’re becoming the most predominant ones within young adults.” (YP20, female with ADHD). This casual approach to romantic relationships might come from the fact that young adulthood is the period during which young people start to learn what a romantic relationship is, and they may not yet have the adequate skills to know how to maintain it. Therefore, navigating relationships through a learning curve may be a common thing.

As indicated by one participant, learning about romantic relationships by oneself meant having had to “learn the hard way” (YP14, male with ADHD), which implies many struggles. Notably, YP17 (a male with ADHD) suggested that romantic relationships “can’t be taught”, similarly, YP14 (a male with ADHD) stated that learning by experience is “the only way” to gain knowledge related to relationships. Those views might be developed as a consequence of the lack of education related to romantic relationships many participants in this study reported. However, an adequate education related to this topic might contribute to better outcomes of romantic relationships for young adults in general.

Given that many participants in this study learned to navigate their romantic relationships by themselves, many encountered difficulties including communication issues within those relationships. Lack of expressing one’s feelings was a significant deterrent to sustaining a good romantic relationship as stressed by several participants. For example:

[…] it was really hard for you know us to have a full conversation about things […] it’s hard to, you know, get her to really speak about what she wanted to say and was feeling at the time […] (YP25, autistic male)

Being direct and literal in communication, which is a common feature associated with ASD, may also contribute to challenges within romantic relationships:

I rarely read between the lines, so he has to be very specific with me and if it’s not, if it’s not, then there’s trouble. Yeah, and at the same time, when I'm quite direct that can also sometimes bring trouble. (YP26, autistic female)

The communication challenges may also be exacerbated by ADHD characteristics as suggested by one young person with this condition:

I don’t want to completely blame this on ADHD, even I’m sure that’s a factor in it. But I’m, I’m definitely very quickly frustrated by small things […] my ADHD doesn’t just affect the romance. It even affects, like how I interact with people […] (YP13, female with ADHD)

Good communication between the couple, however, is one of the variables that affect the overall quality of a romantic relationship [66]. Indeed, some participants emphasized the importance of good communication between them and their partners for a romantic relationship to prosper. From their narratives, it is clear that navigating the complicated world of romance is a challenge, which could be reduced if young people were given adequate support in this context. However, at present, it appears that they are left with their own limited understanding of the topic to create, inevitably by trial and error, their romantic relationships.

Subtheme: Neurodiversity-Driven Obstacles in Romantic Relationships

This lack of adequate sexuality education related to romantic relationships had a substantial impact on some ND young adults (autistic young people and young people with a dual diagnosis) since they reported having little or no romantic relationship experiences, due to, for instance,“[…] I just don’t know in practice how I can actually do it […]” (YP29, autistic female) and “how it works” (YP32, female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD). Although NT young adults also received no education on this topic, they might learn about it through experience (as reported earlier). However, for a ND young person, due to their impairments in social interactions, investigating relationships through trial and error may create problems. As additionally reported by some single ND young people, they “long to be loved” (YP29, autistic female) hence romantic relationships are something they desire.

For some ND young adults, the lack of understanding of inappropriate behaviors in the context of romantic relationships may create further barriers to achieving a romantic relationship. Some reported exhibiting inappropriate behaviors unintentionally, which might again be the result of a lack of adequate knowledge. For example, YP23 (autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man) described that they unintentionally stalked their ex-partner, which consequently had a detrimental impact on their relationship. That young person emphasized that they had challenges with distinguishing which things are right from which are wrong, but they would never like to hurt another person intentionally. This impaired social competence, however, often got that young person in trouble: “I used to get in trouble a lot for like going, hugging people who didn’t want to be hugged, even though that was like a friendly gesture.” (YP23, autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man). Difficulties with recognizing boundaries and “hidden social roles” (YP31, ASD co-occurring with ADHD) were other vital aspects reported by some ND participants that could potentially contribute to problems with romantic relationships: “[…] I’ve crossed an age boundary. And, you know, like, actively hurt somebody because of it. Because, you know, I’ve not recognized some sign.” (YP23, autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man).

Furthermore, some ND young adults, due to having inadequate knowledge related to sexuality and romantic relationships, might feel vulnerable to entering relationships: “I wasn’t [in a relationship] because I think there was always that fear around, especially because I was so young then I was so vulnerable because of, you know, as having Asperger syndrome.” (YP30, autistic female). Some might be more vulnerable to experiencing bullying from peers, which subsequently may affect their perceptions about their future romantic relationships: “I have very low aspirations romantically because of the bullying […]” (YP23, autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man). This vulnerability may imply a need for adequate support that would help ND young individuals increase their self-confidence in establishing romantic relationships.

Moreover, for some ND young people, being in a romantic relationship with an NT person may also create a challenge: “I think what didn’t work was my partner wasn’t autistic. I think they didn’t understand a lot about autism and how that worked and that creates a lot of arguments.” (YP28, autistic female). To fit in the neurotypical world, some ND young adults may need to ‘mask’ their differences and hide their true selves in order to be accepted: “[…] it’s like, pretending to be fine when you’re not.” (YP24, autistic male). The indication that the current sexuality education is not adjusted to the needs of ND young people and thus leaves many of them without basic knowledge related to romantic relationships may inevitably create feelings of discrimination and a consequent need to fit into society by ‘masking’. This suggests a need for raising greater awareness related to neurodiversity in society as this may help to create more open societal attitudes toward neurodiversity.

The existing lack of adequate information related to sexuality and a consequent lack of understanding of some sex-related issues may additionally cause fear in some ND young adults. For example, fear of intimacy was one of the obstacles to creating romantic relationships for some autistic young people and young people with a dual diagnosis: “I have a big fear of intimacy, and I want it, I’m still very scared of it. And that’s also a very stressful thing I have in my mind, as long as I don’t know anything about intimacy either.” (YP31, female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD). Fear of intimacy does not mean that a person is not interested in intimacy; on the contrary, they might “[…] want it […]” (YP31, female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD), however, the fear may be too strong to try to be intimate with someone. Additionally, due to a lack of adequate sexuality education, the person might lack an understanding of what intimacy is and this may create a fear of the unknown [67]. The discrimination that some ND young adults may experience may additionally make them feel unworthy of intimate relationships as indicated by YP31 (female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD): “[…] I don’t really deserve intimacy.” It may be suggested that focusing on information related to intimacy and the potential fear of it among ND young adults, and consequent ways of managing it during sexuality education may be essential.

Furthermore, YP33 (female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD) spoke about having many asexual friends and voiced the necessity for asexuality to be “appreciated rather than assuming that heterosexual intimate relationships were a norm.” Another participant’s (YP32, female with ASD co-occurring with ADHD) emphasis on stating that “[…] asexuality is […] not abnormal […]”, may indicate that, due to a lack of inclusive sexuality education (as reported earlier), some young people may feel excluded from society as if they were ‘not normal’.

The narratives of some ND participants also drew attention to mental health problems and their consequent effect on romantic relationships. For example, anxiety issues appeared to be a serious problem for some ND participants: “[…] it [anxiety] creates for so many people like me that have a lot of anxiety, overthinking and thinking about worst case scenario, I’m actually scared of flirting.” (YP24, autistic male). Anxiety may also be the result of a lack of understanding related to sexuality and romantic relationships. A neurodivergent young person may be “overthinking” (YP24, autistic male), which then may lead to being “scared” (YP24, autistic male), since they were not provided with information that would help them better understand the situation (in the context of their romantic relationships). However, anxiety, as indicated in the preceding comment, might be a serious deterrent to some ND individuals’ romantic relationships. Feeling insecure might also come from mental health problems since it may be linked to, for example, depression [68]. For some ND young adults, feeling insecure was an essential aspect that affected their romantic relationship experiences: “I have […] problems and doubts about whether we will be together in the future, or whether he doesn’t like me anymore and stuff like that.” (YP27, autistic male). The preceding analysis indicates that mental health issues may have serious implications for some young ND individuals’ romantic relationship experiences.

Theme 6: Experience of Abuse in the Young Neurodivergent Population is a Serious Matter

Abuse was another salient subject in the narratives provided by ND young people. It was clear from what they said that abuse is a “serious topic” (YP18, male with ADHD) that “happens far more often than we’re willing to accept” (YP14, male with ADHD). Some participants shared their experiences of sexual or emotional abuse in their intimate relationships (which again could be due to a lack of adequate sexuality education): “My first relationship was very sexually coercive […] And my second one was emotionally abusive.” (YP21, female with ADHD). Young adults who identify as LGBTQ+ are prone to a greater experience of abuse since being a minority person means that “you’re setting yourself up in a way for discrimination” (YP33, male with ASD co-occurring with ADHD). Despite its seriousness, abuse is “a taboo in our society, in our homes and our schools, everywhere.” (YP14, male with ADHD). Additionally, as reported by another young person: “[…] culturally there’s a big stigma around coming forward about rape and abuse.” (YP30, autistic female).

Some young people reported that victims of abuse may also find it very difficult to reveal their experiences to other people especially when it happened to men since “it’s kind of frowned upon” (YP14, male with ADHD). Given this information, it may be indicated that, due to the existing cultural stigma related to revealing abuse, there might be some young adults who experienced abuse in their romantic relationships, however, they may not feel supported to report it. Additionally, this lack of open discussions about abuse may prevent some ND young people, due to their social impairments that are inherent in ASD and ADHD, from recognizing and reporting it. Some ND young adults, however, believed that abuse is “something quite important to talk about” (YP23, autistic genderfluid/non-binary trans man). This societal taboo about abuse was also tangible in one of the participants’ narratives as she apologized to me for sharing her emotional stories about abuse; meaning that abuse is something we (as a society) are not encouraged to talk about.

The existing cultural system puts females who experienced abuse into a position of shame and humiliation making them believe it was their own fault [69]. This position was palpable in the narrative presented by one young woman who experienced sexting abuse:

[…] my parents were told by social services to treat me like I was an addict and told that I would do it again. And in the official social work report, it stated that I liked the attention, and they closed the case. (YP22, female with ADHD)

Another young woman, who experienced sexual abuse, also felt accountable for her victimization: “[…] the boys I dated always over-sexualized me because I’m quite a curvy girl and stuff. In that sense, and like just 'cause the way I dress 'cause I felt confident showing my curves off.” (YP16, female with ADHD). This may indicate that some cases of abuse are not always treated seriously enough when reported by female victims as indicated in the narrative provided by a YP22 (female with ADHD). Additionally, it may also be suggested that some ND young people might lack a (full) understanding of what abuse is and consequently, they feel guilty for being abused (as in the case of YP16, female with ADHD). This, in turn, suggests that there is a need to teach ND young adults topics related to abuse and victimization during sexuality education.

This existing societal taboo against abuse and hence lack of education about it also contributed to a lack of awareness that some ND young adults displayed regarding the subject. Subsequently, this led to adverse consequences in their lives including being in an abusive romantic relationship without recognizing it: “[…] and I didn’t really know that [sexual abuse] was happening and until quite a long time afterwards.” (YP21, female with ADHD). Not only might victims of abuse be unable to recognize that abuse is happening to them, but also abusers may exhibit abusive behaviors toward other people without recognizing and acknowledging their inappropriateness: “[…] I’ve had sometimes in my past experiences where people being forceful and persistent and some of them not even realizing what they’re doing is actually wrong.” (YP16, female with ADHD).

This lack of support and acknowledgment of the importance of abuse was also palpable in some participants’ narratives regarding some educational professionals’ approach to the topic, for example:

[educators] weren’t educated and how to spot stuff [abuse], as well like and even when they were, you know, spotting stuff, there was, you know, some students that were very vocal about things that had happened to them, and there were no support systems in place, there were no lines of reporting, there was nothing […] (YP22, female with ADHD)

This reported lack of support from the teaching personnel might imply that some educators may lack appropriate training to provide adequate assistance to young people concerning abuse. Some young adults, however, believed it was vital to talk about abuse to increase awareness of this very important topic. As pointed out by a young woman (YP22, female with ADHD), adults should teach children to identify what abuse is. She also made a very important point highlighting that “sometimes bad touches don’t always feel bad […]” and this vital information ought to be taught to young people.

The narratives from young adults (ND and NT) indicate that sexuality education in schools/colleges, as well as at young people’s homes, did not provide them with adequate knowledge related to sexuality and romantic relationships. The focus appeared to be on the biological side of sexuality (e.g., reproduction, contraception). Consequently, participants highlighted the importance of offering them space for discussions about positive aspects such as sexual pleasure. The results also demonstrated the lack of focus on romantic relationships during the lessons. Given that many participants also reported experiencing challenges while navigating romantic relationships, it might be speculated that the inadequate teaching related to this subject may have contributed to those challenges. Participants also felt that aspects related to LGBTQ+ were discriminated against across schools/colleges, their homes, and other institutions. Some ND young people additionally reported mental health problems, as well as issues with intimacy, as chief obstacles to achieving their romantic relationships. This implies that discussions about these aspects should be incorporated as essential in sexuality education tailored for this population. Moreover, in this study, pornography was portrayed as a very powerful alternative avenue for gaining sexuality knowledge. Appropriate sexuality education in schools/colleges, and young people’s homes, may decrease the use of pornography as a learning source. This result may also imply the significance of teaching young adults about the consequences of watching pornography.

Participants additionally reported the crucial role of adults (caregivers and professionals) in sexuality education. Some of them indicated that some parents and teachers appeared not fully equipped to teach sexuality topics. This highlights the importance of offering parents and teachers adequate training/support to help them feel (fully) competent to teach this sensitive subject. Offering young adults sexuality education that focuses on delivering teaching relevant to their needs and requirements and that is not outdated is thus crucial.

Discussion

Young people in this study felt that sexuality is a taboo topic in our society and heterosexuality is regarded as a normative construct of sexuality, whereas non-heteronormative relationships are discriminated against. Indeed, Javaid [70] argues that heteronormativity constructs all social action, and it is acknowledged not only as a ‘normal’, desirable sexual practice but also as a normal way of life. This approach was also tangible during participants’ sexuality education, both in their schools/colleges and homes, as many highlighted the lack of teaching related to LGBTQ+ sexuality despite its inclusion in the curriculum [65, 71]. Nash and Browne [62] claim that English schools often lack neutral spaces for non-heteronormative sexualities, which means that LGBTQ+ students experience discrimination within the school environments from peers, teaching staff, the curriculum, and proactive protection. Similarly, Bower-Brown et al. [72] deem that the British educational system is fundamentally inadequate for LGBTQ+ identities.

In accordance with previous literature [e.g., 73,74,75,76], the narratives of many young adults also clearly demonstrated that sexuality education in schools/colleges, as well as with young people’s parents, was very basic covering mostly the biological aspects including puberty and contraception. This result may be justified by the public health approaches to sexuality, which focus firmly on the medical and biological aspects of it and the adverse health outcomes, as opposed to promoting positive features such as sexual pleasure [77]. Young adults additionally consistently reported a lack of education related to romantic relationships; this outcome converges with previous research [78]. The interest and exploration of romantic relationships are common during adolescence, and, at this age, they constitute a key developmental task [79, 80]. Benham-Clarke et al.’ [81] review indicates that despite the formal recommendations that romantic relationships are an essential part of sexuality education in England [65], appropriate formal programs established in UK settings to help young people develop the necessary skills to navigate romantic relationships are sparse [81].

Limited sexuality education pushes some young adults toward alternative means of learning about sexuality; pornography was highlighted as a very powerful source of sexuality information by some participants. Nowadays, young people have very easy, often free access to uncensored images of different sexual acts including violent and risky forms of sex via the internet [82,83,84]. Massey et al. [18] found that 80% of individuals by the age of 19 years had watched online pornography, while Martellozzo et al. [85] suggested that 94% of young adults (aged: 11–16 years) by the age of 14 years had watched online pornography. Viewing pornography may affect young people’s sexual attitudes and behaviors (e.g., casual attitudes to consent, and sexual coercion) [86, 87] and sometimes lead to legal consequences (e.g., sexual offences [often unintentionally] and indecent images of children) in ND individuals [88, 89]. This highlights the importance of providing adequate education regarding pornography [19, 89]. Participants voiced the significance of providing them with easy access to professional services on sexuality-related topics. Indeed, professionals may provide young individuals with appropriate guidance regarding sexuality (e.g., sexual pleasure [90]), clarify any misconceptions about it, and offer gender-sensitive support [91]. However, barriers to professional-young person discussions about sexuality include a lack of initiative, perceived judgment, lack of awareness, and presumed feelings of shame [92, 93].

Young people reported the need for revision and improvement of sexuality education. They listed topics (LGBTQ+ sexuality, sexual pleasure, specific topics related to romantic relationships [e.g., how to gain it], signposting about where to find information and support related to sex and relationships) that were not taught in their schools/colleges, that they nonetheless deemed vital. Teaching related to LGBTQ+ sexuality is crucial, especially when working with autistic young adults since they tend to display greater variety in sexual orientation than their non-autistic peers [94,95,96]. The lack of inclusive sexuality education contributes to the already existing discrimination and stigmatization of minority groups [62, 64, 72].

In terms of romantic relationship experiences, NT young people and young people with ADHD reported having some experiences, however, autistic participants, as well as those with a dual diagnosis, tended to have one or no experiences despite longing for romantic partners. These outcomes converge with previous literature [27, 28, 35, 40, 96, 97]. A casual attitude to romance appeared to be a common trend amongst young adults, especially those with ADHD. Previous research [30, 97, 98] indicated that more symptoms of ADHD were related to greater engagement in more risky sexual behaviors (RSBs) including more unprotected sexual activities and more casual sexual activities. Wallin et al. [99] reported that some young women with ADHD enter many casual romantic relationships due to feeling different, unaccepted, and judged by others, and having low self-esteem and self-image [99].

Participants described their romantic relationships as a complicated world to navigate. Young people’s romantic relationship dynamics are learned and conditioned by their environment; in the early developmental phase, they may acquire constructive interactive styles of communication, which will result in a greater capacity for the expression of positive feelings and the ability to peacefully resolve conflicts within their future relationship [26, 100]. The lack of education related to romantic relationships could contribute to the communication challenges the participants experienced.

Challenges encountered only by ND young adults included a lack of (practical) understanding of how to develop a relationship, a lack of understanding of appropriate versus inappropriate sexual behaviors, and mental health issues such as anxiety. Some autistic young people may have some technical knowledge of sex-related topics, as well as understanding the unspoken rules of social interactions, however, due to their ASD symptomology, they may find it challenging to put that understanding into practice in their everyday life situations [101]. Autistic people may exhibit inappropriate sexual behaviors (e.g., touching another person without their consent [37]), however, it is important to highlight that such behaviors are not typical for the autistic population [102]. In some individuals, the impaired ability to understand social cues and accurately interpret others’ negative responses to their sexual advances may provide the context of vulnerability to displaying behavior that is sexually offensive [e.g., 103]. Anxiety is one of the most common co-occurring conditions in autistic individuals [103,104,105]. This co-occurrence may consequently impact a person’s social skills [7], which are essential in navigating romantic relationships [47]. Notably, individuals with a dual diagnosis experience even greater feelings of anxiety than those with a single (ASD or ADHD) condition [52].

Experience of abuse was a significant concern highlighted by some ND participants mostly with ADHD. Young women with ADHD have been found to experience much higher levels of victimization in their intimate relationships than NT peers (30%—6% in Guendelman et al. [43] and 16.5%—10.3% Snyder [106]). Lower levels of sexual awareness that some ND young people present, when compared to their NT counterparts [29, 40], may diminish their understanding of abuse in a romantic relationship and consequently lead to failure in reporting it [44, 107, 108]. This indicates the importance of teaching young adults, especially ND ones, about abuse in the context of romantic relationships.

Limitations of the Study

The findings of this study, although unique and interesting, should be considered with several important limitations. The interviews were conducted on a one-to-one basis, which might have added some pressure and anxiety to some participants. Measures were undertaken to minimize such possible occurrences by providing participants with the choice of having their cameras off during the recording, as well as by offering them an interview question guide before the recording. All participants were an online sample, which indicates concerns about inclusion and accessibility since only participants with technological access and ability could provide their perspectives on the topic [109]. Notably, although the study was advertised in the UK (England, Ireland, and Scotland), participants were not asked to provide information regarding whether they lived in the UK, and hence the findings should be interpreted with caution for the UK population.

Future Research Directions

This project has provided a preliminary understanding of romantic relationship experiences and sexuality education in three groups of ND young people. Future research is, therefore, vital to further investigate this area to help gain a greater understanding of this topic and establish greater avenues of support for these groups of the population in terms of their sexuality education and romantic relationships. Specifically, further research is important to investigate sexuality education in schools to establish effective ways of teaching that would be appropriate for the ND young population [74]. The explorations of the topic should include young people’s and their parents’ perspectives [35, 74], as well as educators’ views including ND educators [110, 111]. There is still a pressing need to address these areas by both qualitative and quantitative designs [see 54]. Quantitative research could help gather a vast amount of data on the topic and thus provide generalizable findings to a greater population. Additionally, the results could allow for the investigation of the similarities and differences related to specific aspects of sexuality education and romantic relationship experiences amongst the four groups of young people (with ASD, ADHD, ASD co-occurring with ADHD, and NT). Furthermore, previous research has shown that autistic females report experiencing more negative sexual events than their male counterparts and non-autistic females [39, 41], as well as showing lower levels of sexual awareness when compared to their non-autistic peers [29]. Similarly, females with ADHD have been found to have more sexual experiences [97], as well as shorter-lasting romantic relationships [30] than their peers without the condition. Further quantitative exploration of these areas including gender differences, as well as trying to establish ways of potential support to decrease these discrepancies between ND young people and their NT counterparts is therefore vital. Qualitative designs, however, might better shed light on some aspects/details related to sexuality and romantic relationship experiences in young people, which may not be possible to be captured by quantitative studies [125].

In this study, only young people between the ages of 18–25 years old were invited to take part, which consequently limited the accuracy of the provided information about the current system of sexuality education since participants discussed their experiences from a few years previously. However, the sexuality education curriculum in England was reformed in 2019 [65]. Thus, to ensure the most up-to-date information on current sexuality education, it would be beneficial to include younger groups of people in future research. Due to ethical considerations, however, this was not possible for this project. Additionally, in this research, participants with ASD co-occurring with ADHD comprised the smallest sample, and although they offered important insights into the topic, it would be valuable to include a greater number of participants with a dual diagnosis to receive a greater variety of perspectives on the topic from this population. Equally, mainly young people of White ethnic backgrounds took part in the study; including participants of different ethnic backgrounds and gaining their perspectives on sexuality would be useful, especially since cultural aspects play essential roles in shaping approaches to sexuality and romantic relationships.

Practical Recommendations and Implications

As highlighted by young people in this study, it is important to shift the current sexuality education policy and associated practice to make sexuality education provision more relevant and positive for young people, especially the ND groups [see also 125], who, as indicated in this research, tend to experience greater challenges than their NT peers while navigating romantic relationships. This could be achieved by incorporating the following recommendations:

-

Including in the curriculum the currently non-existent topics such as sexual pleasure [see 77, 113], LGBTQ+ sexuality [see 114, 115], teaching related to pornography [see 116], and teaching related to romantic relationships [see e.g., 26, 29, 32], as well as adopting an inclusive language/terminology in all schools/colleges.

-

Given that some autistic participants reported problems with recognizing appropriate versus inappropriate sexual behaviors, it may be important to provide them with adequate knowledge related to this topic. This could be achieved by incorporating social stories portraying sexual behaviors, followed by young person-adult (teacher/parent) discussions [see 117].

-

Topics recommended by participants with a dual diagnosis included asexuality.

-

Young people with ADHD recommended the introduction of teaching related to rejection (how to manage it) [see 118] as well as recognizing bad romantic relationships.

-

Further insights into improving sexuality education for young people, as highlighted by participants, was providing appropriate resources for teaching sexuality, for example, by applying technology in teaching [118].

-

Incorporating discussions related to sexuality and romantic relationships to make the lessons more interactive would also be beneficial as reported by some participants [see also 101].

-

Young people (particularly ND groups) voiced feeling vulnerable to experiencing abuse; therefore, professionals working with young people (e.g., educators, social and health workers), would benefit from receiving adequate training that would help them recognize signs of abuse in young people and also be aware of the barriers that young people may have when facing the disclosure of abuse. The training could specifically focus on the channels enabling those professionals, through asking questions and building trustful relationships with vulnerable young people, to be able to adequately identify signs of any potential abuse and accumulate suitable information from a variety of sources over time on the issue [119].

-

Increasing awareness about abuse by providing school-based educational programs targeting not only young people but also their parents, families, and other adults who might be in a position to intervene in case of potential child abuse might also be useful [120].

-

Efforts could be channeled to support ND young people with mental health issues, specifically anxiety. This, subsequently, may increase their confidence in trying to create romantic relationships. As reported by Schnitzler et al. [121], there is a link between people’s mental health and sexual health and hence these two phenomena should be approached holistically.

-

Another crucial facet stressed by participants was involving parents [see also 123] and professionals (e.g., mental health nurses) [see 73] in helping to shape sexuality education for young people.

-

Based on some participant’s reports regarding the parental discriminative approach to their LGBTQ+ sexuality, providing support and education for parents about LGBTQ+ sexuality [see also 62] might be beneficial as it might help some parents to have a more open and supportive attitude toward their children’s sexuality and consequently discuss it with them.

-

Given that some participants reported that some parents and teachers may lack adequate skills to discuss sex-related issues with them, ensuring that parents and teachers receive training/support to help them feel (fully) equipped in this respect may be crucial.

Conclusion

The findings demonstrated that many young adults felt that sexuality education in their schools/colleges was inadequate as it did not include some vital aspects of sexuality (e.g., LGBTQ+ sexuality, sexual pleasure, abuse, romantic relationships). Young people also reported having limited parent–child sexuality-related communication due to, for example, the parental lack of appropriate skills to conduct such discussions. Notably, some ND young people reported lacking knowledge pertaining to romantic relationships including basic aspects of what a romantic relationship means and how to gain it, despite their desire to have a romantic partner. Importantly, young people may need support from educators, caregivers, and professionals to learn to navigate the complicated world of romance and gain the skills required to create and maintain (healthy) romantic relationships.

Data, Materials, and/or Code availability

A copy of the data will be offered to the UK Data Archive in 2024.

Notes

Different groups of communities have different preferences in terms of describing ASD [123]. Professionals preferred the use of person-first language (person with autism), whereas autistic people and parents of autistic children (to a lesser degree) preferred the identity-first language (autistic person). Based on this, to respect the preference of autistic individuals, the term autistic person will be used where appropriate throughout this paper. Young people without diagnoses (ASD/ADHD) are referred to as neurotypical young people (NT).

Although the study was advertized in the UK, participants were not asked directly about this, and therefore caution in interpretation is advised.

References

American Psychiatric Association (APA). DSM–5–TR, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association (2023).

Enner, S., Ahmad, S., Morse, A.M., Kothare, S.V.: Autism: considerations for transitions of care into adulthood. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 32(3), 446–452 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000882

Lord, C., McCauley, J.B., Pepa, L.A., Huerta, M., Pickles, A.: Work, living, and the pursuit of happiness: vocational and psychosocial outcomes for young adults with autism. Autism 24(7), 1691–1703 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320919246

Billstedt, E., Anckarsäter, H., Wallinius, M., Hofvander, B.: Neurodevelopmental disorders in young violent offenders: Overlap and background characteristics. Psychiatry Res. 252, 234–241 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.004

Lai, M.C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Ameis, S.H., et al.: Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 6(10), 819–829 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

Hollingdale, J., Woodhouse, E., Young, S., Fridman, A., Mandy, W.: Autistic spectrum disorder symptoms in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytical review. Psychol. Med. 50(13), 2240–2253 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719002368

Zablotsky, B., Bramlett, M.D., Blumberg, S.J.: The co-occurrence of autism spectrum disorder in children with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 24(1), 94–103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717713638

Thapar, A., Livingston, L.A., Eyre, O., Riglin, L.: Practitioner Review: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder–the importance of depression. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 64(1), 4–15 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13678

Toseeb, U., Asbury, K.: A longitudinal study of the mental health of autistic children and adolescents and their parents during COVID-19: part 1, quantitative findings. Autism 27(1), 105–116 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221082715

Allen, J.P., Narr, R.K., Kansky, J., Szwedo, D.E.: Adolescent peer relationship qualities as predictors of long-term romantic life satisfaction. Child Dev. 91(1), 327–340 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13193

Connolly, J., McIsaac, C.: Adolescents’ explanations for romantic dissolutions: a developmental perspective. J. Adolesc. 32(5), 1209–1223 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.01.006

Huuki, T., Kyrölä, K., Pihkala, S.: What else can a crush become: working with arts-methods to address sexual harassment in pre-teen romantic relationship cultures. Gend. Educ. 34(5), 577–592 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2021.1989384

Horn, E.E., Xu, Y., Beam, C.R., Turkheimer, E., Emery, R.E.: Accounting for the physical and mental health benefits of entry into marriage: A genetically informed study of selection and causation. J. Fam. Psychol. 27(1), 30–41 (2013)

Klencakova, L.E., Pentaraki, M., McManus, C.: The impact of intimate partner violence on young women’s educational well-being: A systematic review of literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 24(2), 1172–1187 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211052244j

Woodward, L.J., Fergusson, D.M., Horwood, L.J.: Romantic relationships of young people with childhood and adolescent onset antisocial behavior problems. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 30(3), 231–243 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015150728887

Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J., Siebenbruner, J., Collins, W.A.: A prospective study of intraindividual and peer influences on adolescents’ heterosexual romantic and sexual behavior. Arch. Sex. Behav. 33(4), 381–394 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ASEB.0000028891.16654.2c

Alvarez, M.J., Pegado, A., Luz, R., Amaro, H.: Still striving after all these years: between normality of conduct and normativity of evaluation in casual relationships among college students. Curr. Psychol. 4, 1–11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02344-9

Freeman, H., Simons, J., Benson, N.F.: Romantic duration, relationship quality, and attachment insecurity among dating couples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(1), 856 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010856

Massey, K., Burns, J., Franz, A.: Young people, sexuality and the age of pornography. Sex .Cult. 25(1), 318–336 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09771-z

Boisvert, S., Poulin, F., Dion, J.: Romantic relationships from adolescence to established adulthood. Emerging Adulthood 1–12, 21676968231174083 (2023)

Tuval-Mashiach, R., Shulman, S.: Resolution of disagreements between romantic partners, among adolescents, and young adults: Qualitative analysis of interaction discourses. J. Res. Adolesc. 16(4), 561–588 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00508.x

Blumenstock, S.M., Quinn-Nilas, C., Milhausen, R.R., McKay, A.: High emotional and sexual satisfaction among partnered midlife Canadians: Associations with relationship characteristics, sexual activity and communication, and health. Arch. Sex. Behav. 49(3), 953–967 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01498-9

Lawrence, E., Pederson, A., Bunde, M., Barry, R.A., Brock, R.L., Fazio, E., Mulryan, L., Hunt, S., Madsen, L., Dzankovic, S.: Objective ratings of relationship skills across multiple domains as predictors of marital satisfaction trajectories. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 25(3), 445–466 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508090868

Herbert, A., Fraser, A., Howe, L.D., Szilassy, E., Barnes, M., Feder, G., Heron, J., et al.: Categories of intimate partner violence and abuse among young women and men: latent class analysis of psychological, physical, and sexual victimization and perpetration in a UK birth cohort. J. Interpers. Violence 38(1–2), NP931–NP954 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221087708

Krahé, B., Berger, A., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Bianchi, G., Chliaoutakis, J., Fernández-Fuertes, A.A., Zygadło, A., et al.: Prevalence and correlates of young people’s sexual aggression perpetration and victimisation in 10 European countries: a multi-level analysis. Cult. Health Sex. 17(6), 682–699 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.989265