Abstract

Neurodivergent young people tend to struggle with building and maintaining their romantic relationships. Despite this, there appears to be a lack of appropriate sexuality education delivered to them. This review aims to present and discuss the most current literature (conducted between 2015 and current) on romantic relationships and sexuality education in young people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and ASD co-occurring with ADHD. Six internet-based bibliographic databases were used for the present review that followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Thirty-one studies were identified in this review. Twenty-six studies investigated the topic in the autistic young population. Four studies explored qualitatively and 11 quantitatively young people’s perspectives of their romantic relationship experiences. One study investigated qualitatively and three quantitatively young people’s perspectives on sexuality education. One study explored qualitatively and five quantitatively young people’s romantic relationship experiences and two explored qualitatively and three quantitatively sexuality education from caregivers’ perspectives. Five studies (all quantitative, self-reports) investigated romantic relationship experiences in the young population with ADHD. The studies conducted on the topic from the educational professionals’ perspectives were absent in the literature. The literature was also non-existent on the topic in the population with ASD co-occurring with ADHD. To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first review exploring romantic relationships and sexuality education in three groups of neurodivergent young people (with ASD, ADHD, and ASD co-occurring with ADHD).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

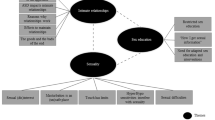

Romantic relationships comprise a fundamental part of young people’s development [1], and sexuality education offered in schools/colleges, as well as young people’s homes, plays a vital role in shaping their understanding of and attitudes toward their own sexuality [2, 3]. While substantial research focused on exploring sexuality education and romantic relationships in typically developing (TD) young people [e.g., 4, 5], there appears to be a lack of in-depth exploration of the topic in the neurodivergent (ND) young population.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are classified under Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs) [6]. These two conditions tend to overlap in terms of their symptomology, have a strong genetic influence, possible environmental impacts, and are prominent in men [7]. The co-occurrence of autism with ADHD is associated with a greater likelihood of co-occurring additional conditions such as behavioral disorder, anxiety disorder, mood disorder, and developmental disorder [8]. NDDs persist into adulthood [9, 10] and cause impairments at various levels of a person’s functioning including personal and social [1, 6]. A substantial number of autistic individuals also meet the criteria for the ADHD diagnosis [8].

Individuals with a dual diagnosis (ASD co-occurring with ADHD) exhibit higher deficits in adaptive abilities [11], which include effective communication with others and building relationships [12]. Children with a dual diagnosis tend to exhibit increased rates of behavioral and conduct symptoms, mood disorders, and other psychopathologies when compared to their peers with a single condition (autism or ADHD) [13]. Individuals with a dual diagnosis also show more severe impairments in executive and social processing such as greater impairments in reading other people’s emotions, problems with communication, depression, and anxiety when compared to counterparts with a single diagnosis (autism or ADHD) [11, 14].

Furthermore, individuals with ASD co-occurring with ADHD may exhibit impairments characteristic of both conditions, as opposed to displaying an entirely new phenotype [15]. Mikami et al. [16] assert that individuals with ASD co-occurring with ADHD may not only have decreased motivation to socialize with peers (which is characteristic of ASD), but this reduced motivation may also lead to a lower restrain from untrained competing responses (which is characteristic of ADHD) because the perceived reward for doing so is of less value. The reasons for social interaction difficulties in individuals with ASD co-occurring with ADHD may thus build on one another [14]. The highlighted vulnerabilities may suggest that young people with a dual diagnosis may encounter greater difficulties with creating and maintaining their romantic relationships than their counterparts with only one condition (autism or ADHD). The social functioning of young people with ASD co-occurring with ADHD, however, has received little research attention to date [16].

Research conducted on the topic in the autistic young population has found that some autistic individuals exhibit lower awareness regarding privacy, sexual knowledge, higher concerns about finding a romantic partner, fewer opportunities to meet a potential intimate partner, and shorter romantic relationships than their non-autistic peers [17,18,19,20]. Consistent with this, research has indicated that autistic individuals receive less sexuality education than their typically developing (TD) peers [20,21,22,23,24].

There is a lack of evidence-based sexuality education curriculums tailored specifically for the needs of autistic young people, which would combine the relationship between sexual socialization and sexual behavior [24, 25], and, therefore, there is an urgent need to provide it [24]. Although there have been several calls emphasizing the need for a specific to autistic young people’s sexuality education curriculum, there have still been relatively few explorations of the subject [26]. Sexual health screening and sex education for all young people including autistic young people, however, must remain priorities [27].

Relatively little research has investigated romantic relationships in young people with ADHD [28]. The previous literature highlighted that some young adults with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD report having fewer close relationships, as well as greater problems within them compared to their TD peers [29,30,31]. The literature also highlighted that ADHD symptomatology is contributory to problems with social interactions, lower quality of romantic relationships, higher risk of relationship failures, and higher rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration and victimization [29, 30, 32, 33]. Individuals with ADHD also tend to be forgetful, get easily distracted, be disorganized, fail to meet responsibilities, and they can display anger and verbal and physical outbursts more often than their TD peers [34, 35].

This review aims to explore the literature investigating romantic relationship experiences and sexuality education in three groups of neurodivergent young people (autistic people, people with ADHD, and people with ASD co-occurring with ADHD; age groups maximum 25 years old) from the perspectives of young people, caregivers, and educational professionals.

Method

Six internet-based bibliographic databases were used for this review: SalfordUniversityJournals@Ovid; Journals@Ovid Full Text < March 03, 2022 >; APA PsycArticles Full Text; APA PsycExtra < 1908 to February 14, 2022 >; APA PsycInfo < 2002 to February Week 4 2022 >; Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily < 2018 to March 03, 2022 >. The search was conducted to identify the existing literature on sexuality education and experience of romantic relationships in the autistic young population, the population with ADHD, and the population with ASD co-occurring with ADHD. The date limit placed on the conducted search was 2015-current. This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11, 12]. The PRISMA guidelines comprise a four-phase flow diagram and a 27-item checklist, which is regarded as vital to providing clear reporting in a review with a systematic search [11, 16]. The search on all six databases was conducted on 4th March 2022, all duplicates (307) were excluded before obtaining references. Table 1 contains the terms used in the search.

The search returned 939 articles, of which 307 were duplicates. After removing the duplicates, the search returned 632. Of the 632, 508 were eliminated (468 by reading the abstract for they were discordant with the topic area, 34 were dissertations, 5 were foreign papers, and 1 was a duplicate). Consequently, 124 were assessed for eligibility. Out of the 124, 95 were excluded since they did not meet the inclusion criteria. As a result, only 29 articles were relevant to the topic and met all the criteria (Fig. 1 details the process of screening papers from 632 to 29). Google Scholar searches were additionally carried out in order to reduce the chance that relevant articles were missed because they were not included in the database search. Key search terms (used in the database searches outlined above) were entered into Google Scholar on 6th March 2022 and two further articles were identified [31, 36]. The reference section for relevant articles and reviews was also screened for any potentially relevant articles that may not have been identified in the database searches, however, no additional papers were found.

Flow diagram for systematic literature review (Adapted from Page et al. [94])

In total, 31 papers met the inclusion criteria for this review. The papers identified were based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Human study population.

-

2.

Studies that looked at the neurodivergent populations of young people (with a mean age maximum of 25 years old); specifically autistic young people, young people with ADHD, and young people with ASD co-occurring with ADHD (the diagnosis of the condition may be formal, self-reported or parent/caregiver reported) and explored sexuality education and romantic relationship experiences; studies which explored that topic from the perspectives of young people, caregivers, and educational professionals.

Exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Non-human study population.

-

2.

Papers that focused on ASD, ADHD, and ASD co-occurring with ADHD with co-occurring other disorders, e.g., Intellectual Disabilities.

-

3.

Papers that did not include an ASD/ADHD participant group.

-

4.

Papers that were not peer-reviewed articles.

-

5.

Papers that were the reviews.

-

6.

Article comments.

-

7.

Papers not published in English.

-

8.

Studies that included participants whose mean age was greater than 25 years old, or which did not provide the mean age of participants, however, included participants within the age range greater than 25 years old.

-

9.

Intervention studies.

Figure 1 describes the process for identifying the relevant articles.

Results

In total, 31 papers met the eligibility criteria and thus were included in this review (see Table 2 for all qualitative studies on the population with ASD, Table 3 for all quantitative studies on the population with ASD, and Table 4 for all quantitative studies on the population with ADHD). Eighteen studies [17, 23, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] explored the topic in the autistic population quantitatively, six studies [18, 52,53,54,55,56] qualitatively, one was a mixed method design [57], and one was a case study [58]. Qualitative studies on the topic in the population with ADHD were absent from the current literature and only five papers [31, 36, 59,60,61] explored the topic quantitatively. No studies were identified on the topic in the population with ASD co-occurring with ADHD.

Studies on the Autistic Population

Eighteen (69%) [17, 23, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] of the 26 studies identified in this review on the autistic population were conducted quantitatively via questionnaires, six studies (23%) utilized a qualitative design including semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups [18, 52,53,54,55,56], one (4%) was a mixed-methods design [57], and one (4%) was a case study [58]. The identified studies provided accounts on the topic of autistic young people and their caregivers. There was no research found on the topic from the perspectives of educational professionals. Within the identified studies, the collective sample comprised 7.721 participants out of which 1. 833 were diagnosed with ASD and 877 were caregivers of autistic young people. Notably, only one study [49] comprised over 46% of the total sample across all studies. The age range of participants across the studies (self-reports) was 12–39 years, mean age range was 16.67–25.13 years. The autistic male–female ratio across all studies (self-reports) was approximately 46% versus 47% and 7% had other gender identities.

Eighty-one percent of the identified studies carried out either a screening and/or diagnostic assessment to confirm participants’ diagnoses of ASD [17, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43, 50, 51] or the diagnosis was provided/confirmed by a clinical record [18, 23, 44,45,46, 48, 55,56,57]. Some studies reported they recruited autistic participants; however, they provided no information on how participants’ diagnoses were obtained [52, 58], or parents reported ASD [47, 49, 54]. In Cheak-Zamora et al.’ [18] study, 40.7% of the autistic participants also self-reported having a co-occurring ADHD diagnosis, so although this study did not focus on the population with ASD co-occurring with ADHD, some of the findings might also be interpreted for this population. Thirty-five percent of the studies [17, 23, 39, 42, 49,50,51, 57] included a control group alongside the autistic group, and 4% (1 study) was a case study [58].

Findings from Qualitative Research in the Autistic Population

Autistic Young People’s Narratives of Their Experiences of Romantic Relationships and Sexuality Education

Only four studies [18, 52, 53, 56] and one case study [58] were identified which provided autistic young people’s qualitative narratives of their experiences of romantic relationships. The findings highlighted that many autistic young people were single although many of them longed for a romantic relationship [18, 56]. Autistic men [53] reported having some experiences of romantic relationships, albeit several challenges related to their sexuality and relationships have been noted including sensory and information processing concerns such as recognizing feelings of attraction or physical arousal, compulsive interests, and difficulties with social communications. Similar issues were reported by other participants [18, 53, 56]. Cheak-Zamora et al.’ [18] study also highlighted that some autistic individuals would prefer to be in a romantic relationship with another autistic person or with someone who would understand their condition (ASD), as opposed to with someone else.

Some participants expressed feelings such as confusion, sadness, and frustration due to their lack of romantic partners, as well as anxiety caused by their lack of understanding of how to build romantic relationships [18, 52]. Some autistic young people reported sexual and gender diversity [52] and, interestingly, autistic women were found to display lower levels of sexual interests than autistic men [18]. The findings from the case study [58] demonstrated that a young, in this case, autistic man, displayed inappropriate sexual behavior by providing sexual services to others in exchange for money, without realizing the inappropriateness of such activities [58].

Only one study [57 (qualitative section)] was identified that investigated autistic young people’s qualitative narratives about their sexuality education. In contrast to their non-autistic peers, autistic young people reported high levels of social anxiety and problems with socializing and bonding with others. This, in turn, limited their opportunities to learn about sexuality from peer groups.

Caregivers’ Narratives of Their Autistic Children’s Romantic Relationship Experiences and Sexuality Education

Only one study [55] provided caregivers’ qualitative narratives of their autistic children’s romantic relationship experiences. Some caregivers expressed concerns about their children’s sexual safety, loneliness, being bullied by their peers, and the possibility of them having no future romantic relationships. Some parents felt concerned about their preparedness and self-efficacy to discuss sex-related topics with their children and many of them felt unable or helpless to support their children with their sexual behaviors.

Caregivers’ qualitative narratives of their autistic children’s sexuality education were identified in two studies [54, 56]. Some parents expressed feeling a lack of support from the professional services on their sexuality-related communication with their autistic children [49]. Many parents expressed positive views on the possibility of targeted sexuality education, as well as the use of technology (e.g., videos, applications) to facilitate their autistic children’s sexuality learning [54]. Interestingly, across both studies [54, 56] some parents were more concerned about adverse outcomes of their children’s sexual experiences (e.g., sexual exploitation, sexual offenses), as opposed to goals of overall healthy sexuality. Several caregivers also voiced concerns about pornography (that their children may perceive it as normal sexual behavior) [56]. The majority (88.5%) of the caregivers across those studies were mothers who discussed mostly (80.5%) their sons’ experiences.

Findings from Quantitative Research in the Autistic Population

Autistic Young People’s Self-reports on Their Experiences of Romantic Relationships and Sexuality Education

Ten papers [17, 37,38,39,40 (section on self-reported experiences), 42, 43 (section on self-reported experiences), 23, 49, 50] provided quantitative self-reports of romantic relationship experiences in autistic young individuals. The findings highlighted that many autistic young people (73–77.9%) showed an interest in romantic relationships [23, 43] at a similar level to their TD peers (88.5%) [23]. Many were currently single (80+%) [49] and some felt anxious due to their lack of understanding of how to build romantic relationships [42]. Autistic young people (80.9%), however, similarly to their TD peers (91.3%), believed it was important to be in a long-term relationship in the future [23].

The majority of autistic men (63.4–82%), similarly to their TD counterparts (75.9–93%), reported heterosexual attractions [23, 49]. A substantial number of autistic women (over 90% in Bush et al. [37] and 50% in May et al. [49]), however, were found to display other sexual orientations than heterosexual. Conflicting evidence was also reported; autistic women (63%), similarly to their TD peers (69.3%), identified as heterosexual [23]. The discrepancy might be explained by differences in the utilized methodology in the studies. Again, autistic women were found to display lower levels of sexual interest than autistic men [50] and their TD peers [17, 23]. Despite this, they displayed more sexual experiences than autistic men [49, 50] but less than TD women [17, 23]. Importantly, autistic women reported having more regretful sexual experiences and were more likely to experience an unwanted sexual event than autistic men and TD women [23, 50].

Most of the autistic men (over 80%) [23, 39, 40], had some experience of romantic relationships, although they reported fewer experiences and showed a lower interest in sexual activities than their TD counterparts [23]. Some men reported negative sexual experiences including being victimized due to a lack of knowledge about sex and being rejected by others [23]. Across two studies [39, 40], only a minimum number of men reported using coercion to engage in sexual activities with someone (3 autistic men—2 TD men) or being coerced by someone (2 autistic men—0 TD men). Interestingly, some (43.9%) autistic men were concerned that their sexual behaviors might be misunderstood by others and some (31.7%) that they might be taken advantage of, compared to 21.4% and 10.7% of TD participants reporting such concerns respectively.

Three studies [57 (quantitative section), 23, 51] provided quantitative accounts of autistic young people’s sexuality education. The findings across two studies [23, 57] demonstrated that autistic young individuals displayed substantially lower sexuality understanding (autistic group: 42.6%, TD group: 15.4%) [23] including sexual consciousness, sexual monitoring, sexual assertiveness, and sex appeal consciousness [57] than their TD peers. Autistic women demonstrated lower levels of understanding of their own emotions, sexual thoughts, sensations, and how they presented sexuality to others compared to TD peers [17]. Interestingly, 38.8% of autistic young people, compared to 24% of their TD peers, reported having mostly learned about sexuality in schools, and only 7.5% of autistic people learned from their peers, compared to 29.8% of TD young people [23]. Conflicting evidence emerged from Visser et al.’ [51] study, which showed that around 50% of autistic adolescents, similarly to their TD peers, could appropriately evaluate and judge illustrated sexual situations (whether they were socially appropriate or not).

Caregivers’ Reports of Their Autistic Children’s Romantic Relationship Experiences and Sexuality Education

Six studies [38 (section on parental perspectives), 41, 43 (section on parental perspectives), 44, 45, 48] provided parental quantitative accounts of their autistic children’s romantic relationship experiences. Across those studies, the parental tendency to undervalue their children’s romantic interests in other people [43], sexual experiences such as masturbation and orgasm [38], as well as sexual victimization and problematic behaviors [43] were highlighted. Some caregivers expressed concerns about their children’s sexual safety, loneliness, being bullied by their peers, and the possibility of them having no romantic relationships in the future [45]. Some parents highlighted that their children exhibited inappropriate sexual behaviors including undressing in public, kissing/hugging strangers, or trying to have sexual intercourse with someone without their consent, deviant masturbation, paedophilia, fetishism, voyeurism, and sadomasochism [41, 44, 48]. Despite those problems, some parents felt concerned about their preparedness and self-efficacy to discuss sexual topics with their children [44]. Importantly, across all studies, the majority of parents/caregivers were women (86%) (Fernandes et al. [41] did not specify caregivers’ gender) who mostly discussed their sons’ (66%) sexual and romantic experiences.

Three articles [44, 46, 47] provided parental quantitative accounts of their autistic children’s sexuality education. Across these studies, predominantly mothers (88.9%+) provided their perspectives on their children’s (girls [46], men {86.8%} [44]; no information on the children’s gender was provided [47]) sexuality education. Holmes et al.’ [44] study showed that parents of children with more severe symptoms of ASD, irrespective of their intelligence quotient (IQ), had lower expectations regarding their children’s romantic relationships and consequently discussed fewer sex-related topics with them, compared to parents who had higher romantic expectations for their children [44]. The majority of parents (over 80%) used talking/discussion to educate their children about sexuality, not utilizing other methods such as social stories, books, or videos [46, 47]. Many parents (80%), additionally, communicated with their autistic children mostly on basic topics related to sexuality including privacy, private body parts, puberty, and reproductive health (i.e., pregnancy) [46, 47]. Some parents omitted topics that they considered to be insignificant or unnecessary, or, that their adolescent or young adult child was not ready for them. For example, sexual abuse was not discussed by 59% of parents, who reported being able to guard their child against it [47]. Some parents (7%) [47], however, reported being embarrassed to discuss sexual abuse with their children. Topics such as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), AIDS, and contraception were omitted by 40% of parents in the group of children with average/above intellectual abilities and around 85% in the group of children with low intellectual abilities [46] since, according to some parents [47], their adolescent or young adult children were too young for such discussions. Dating and marriage were further topics ignored by some parents (around 25–50% [46]). Importantly, across those studies, some parents reported feeling unprepared or lacking the self-efficacy to communicate about sexuality with their autistic children.

Studies on the Population with ADHD

The total sample across the studies on the young population with ADHD comprised 861 out of which 494 had ADHD. Across the studies, the age range was 12.6–28 years, and the mean age range was 13–19.6 years. The male–female with ADHD ratio across all studies was 65% versus 35%. All studies recruited participants with ADHD verified by a screening tool [31, 36, 59,60,61]. Most studies (80%) [31, 36, 59, 61] included a control group alongside the group with ADHD.

Findings from Qualitative Research in the Population with ADHD

Qualitative studies on the topic in the young population with ADHD were absent in the literature.

Findings from Quantitative Research in the Population with ADHD

Five papers [31, 36, 59,60,61] quantitatively explored the topic of romantic relationship experiences in the young population with ADHD. Across all studies, the findings demonstrated that young people with ADHD experience challenges in their romantic relationships. Some findings highlighted that greater symptoms of ADHD lead to greater challenges with romantic relationships even in the young people who do not fit the criteria for the ADHD diagnosis, due to less ability to engage in relationship maintenance [36]. Greater symptoms of ADHD were also related to greater engagement in riskier sexual behaviors (RSBs) including more unprotected sexual activities, more sexual activities with newly met people, more impulsive sex, more risky anal sex, and sexual activities under the influence of alcohol or drugs [59, 61]. These types of behaviors consequently led some of those young people to develop an STD or become accidentally pregnant more often than their TD peers [61]. The findings also indicated that young women with ADHD were more likely to experience more oral sex activities [59], as well as shorter-lasting romantic relationships [61] than their TD peers. Interestingly, in a study by Rokeach and Wiener [61], there was no significant difference found concerning the quality of romantic relationships (e.g., aggression or abuse) between the ADHD and TD groups.

One study [31] showed that childhood diagnosis of ADHD may predict a five-times (30–6%) greater risk of physical IPV victimization by young adulthood in women with ADHD than TD women. Interestingly, it was the core childhood diagnosis of ADHD, irrespective of other factors including sociodemographic, cognitive, and psychiatric (e.g., poverty, maltreatment, depression, conduct problems), that predicted the risk of victimization in females. Women with persistent ADHD were found to be twice as likely to experience IPV and victimization than those with transient ADHD, and nine times as likely to experience IPV and victimization than TD women [31].

Notably, the current literature contained no studies exploring sexuality education in the population with ADHD. Research on romantic relationships and sexuality education in this group of young people from caregivers’ and educational professionals’ perspectives was also absent from the current body of knowledge.

Studies on the Population with ASD co-occurring with ADHD

No studies were identified which would provide insights into the topic of romantic relationships and sexuality education in the young population with ASD co-occurring with ADHD.

Discussion

This review investigated romantic relationship experiences and sexuality education in three groups of neurodivergent young people (autistic people, people with ADHD, and people with ASD co-occurring with ADHD) from the perspectives of young people, caregivers, and educational professionals.

The literature contained no papers investigating romantic relationship experiences and sexuality education in young people with ASD co-occurring with ADHD. Cheak-Zamora et al. [18], however, reported that 40.7% of the autistic population in their study also self-reported having a co-occurrence of ADHD. This is consistent with the high prevalence of co-occurrence of these two conditions shown in the recent research: 62.7% of children (mean age: 7.5 ± 1.1) [62], 22% of preschool children, and 45% of school-aged children (mean age = 5.0) [63]. This may indicate the possibility that some percentage of the autistic participants in the studies included in this review might also have the co-occurrence of ADHD, however, the studies did not screen for it. Based on the previous findings [8, 13], it might be speculated that young individuals with a dual diagnosis might experience even greater difficulties with building and maintaining their romantic relationships than individuals with a single condition (ASD or ADHD).

Neurodivergent young people (autistic or with ADHD) were found to show similar interests in romantic relationships to their TD peers [17, 18, 23, 36,37,38,39,40, 42, 49, 50, 52, 56], however, they tended to encounter greater challenges navigating those relationships than their peers without the condition (autism or ADHD) [17, 18, 36]. These outcomes resonate with a substantial amount of previous literature [22, 50, 64,65,66]. Notably, in both groups, women, as opposed to men, were found to be more vulnerable to having negative sexual experiences [23, 31, 36, 50, 67], and the autistic group presented lower levels of sexual awareness than non-autistic women [17, 31]. There were no studies identified that would provide an understanding of sexual awareness in the group with ADHD.

In the autistic population, some of the highlighted challenges in romantic relationships were communication difficulties [38, 40, 52] and a lack of awareness of how to establish romantic relationships [18, 56]. Sensory difficulties also hindered some autistic people’s romantic relationship experiences [18, 38, 52]. Sexual and romantic relationship experiences are related to sensory sensitivities and sensation-seeking across numerous sensory processes, including sound, smell, touch, and sight [68]. Sensory features have both positive and negative impacts on sexual and romantic relationship experiences in many autistic people and, hence, they should be considered in education curriculums [68].

Interestingly, some autistic young individuals expressed greater comfort about being in a romantic relationship with another autistic person or someone who would understand their condition (ASD) [18]. Indeed, autistic individuals might show a propensity to establish romantic relationships with other ‘akin’ people (e.g., rejected by society, having untypical interests or impairments in social interactions, or being regarded as ‘weird’) [69]. Studies [23, 38] that focused on romantic relationship experiences in autistic young men demonstrated that they encounter problems with communication in their relationships or finding partners. Autistic women were found to be more vulnerable to having negative sexual experiences [23, 50, 67, 70] and presented lower levels of sexual awareness than TD women [17, 23]; these findings parallel previous research [71].

Some autistic young people were found to exhibit inappropriate behaviors such as selling sexual services [58], or touching another person without their consent [45, 48]. Such types of sexual behaviors, however, are not typical for the autistic population [72]. Kellaher [73] argued that deviant sexual behaviors in some autistic people may imply “counterfeit” deviant sexual behavior, which describes inappropriate sexual behaviors. Such behaviors may be identified as paraphilias, however, they stem from the impairment in social skills and inadequate sexual understanding and experience [74]. Indeed, some autistic young people were found to display much less understanding concerning sexuality than their TD peers [23, 57].

This review also highlights that some parents underestimate their autistic children’s romantic and sexual experiences including sexual victimization and consensual and non-consensual sexual experiences [43]. This might be the result of inadequate parent–child sexuality communication [43]. This outcome converges with previous findings [49] indicating that many autistic young people learn about sexuality by themselves, as opposed to through communication with their parents. Indeed, parents tend to avoid sensitive topics (e.g., STDs, contraception) when conducting discussions about sexuality with their autistic children [46, 47, 54]. Similar findings were reported in previous literature [75, 76].

Across the presented research on the autistic population, some important limitations necessitate highlighting. The majority of the studies [18, 38, 43,44,45,46,47,48, 52, 54, 56] did not include a control group. Given this, it is difficult to determine whether reported experiences by autistic young people and their caregivers are typical only for the autistic population or apply to the young population in general. Interestingly, Joyal et al. [23] claim that, due to the findings showing that some autistic participants scored lower on the questions regarding their interests in sexual behaviors than their TD peers, they were not interested in socio-sexual behaviors. They also add that autistic participants reported lower knowledge regarding sexuality than their TD counterparts. Perhaps the lower outcomes on the questions about interests in sexual behaviors in the autistic group are the results of their lack of understanding of sexuality, as opposed to the lack of interest in sexual behaviors per se. Identifying as asexual in Bush’s [37] study was associated with not having a current sexual partner, having fewer lifetime sexual partners, experiencing less desire for partnered and solo sexual activity, and experiencing fewer lifetime sexual behaviors. The reasons behind one’s lack of sexual experience or sexual partner, however, might not necessarily equate to being asexual.

The current, albeit limited, literature additionally highlights that romantic relationships may also be challenging for many young people with ADHD, for example, in terms of conflict management [36]. Rokeach and Wiener’s [61] study showed no significant difference between the quality of romantic relationships in young people with ADHD and their TD peers. That finding was inconsistent with research by VanderDrift et al. [36]. Although both studies [36, 61] were conducted quantitatively, the different measures used and their definitions of ‘quality of relationships’ might have influenced the results. One study [60] showed that social skills were not associated with the outcomes of romantic relationships in some young people with ADHD. In terms of romantic relationships, the similarity in communication and social-cognitive skills between the partners attracts one another [77, 78]. This may suggest that young people with ADHD build romantic relationships with people who represent similar social skills to theirs. This, in turn, may indicate, given the maladaptive coping mechanisms observed in the romantic relationships in some young people with ADHD [36, 79], that long-lasting relationships for some young individuals with ADHD may not necessarily mean successful and desirable relationship experiences.

Some young individuals with ADHD might be promiscuous and more vulnerable to developing an STD or becoming accidentally pregnant than their TD peers [61]. Previous research demonstrated that hyperactivity/impulsivity and combined ADHD symptoms were linked with heightened RSBs such as having sex without protection, multiple sexual partners, sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and unintended pregnancy [80,81,82,83,84]. This review also indicates that some young individuals with ADHD, especially women, may experience greater rates of IPV, perpetration, and victimization in their romantic relationships than TD individuals [31]. These findings are supported by a great body of literature investigating older groups of individuals with ADHD [33, 84,85,86]. The lack of understanding of sexual concepts, misconceptions regarding intimacy, and being shamed for asking questions regarding sexuality, may contribute to relationship difficulties encountered by some young people with ADHD [87]. The current body of research, however, lacks insights into sexuality education in this group of the population.

Notably, a restricted sample size, which failed to obtain the statistical power, constituted a limitation across some of the research [36, 59, 61] on the population with ADHD, therefore, the generalization of the results in those studies should be treated tentatively.

The current literature also lacked the perspectives of educational professionals on the topic, however, views from educators are vital [54] as they should contribute to developing the curriculums of sexuality education for neurodivergent young people [48].

Creating good sexuality education that acknowledges the neurodivergent population and establishes reliability to their voices and that holds the notion that sexual health “is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity” [88, p.5] is therefore crucial.

Limitations

Possibly, not all relevant articles were identified in the search on the databases. Additional searches, therefore, were carried out on Google Scholar and the reference section for relevant articles and reviews was screened for any potential, relevant articles that may not have been identified in the database searches. Only peer-reviewed papers written in English were included in this review, excluding other materials which were published on the topic.

Clinical Implications

This current review identified several important clinical implications. Autistic young individuals have specific requirements for sexuality education, which differ from the needs of their TD peers [57]. The current sexuality education provided in schools might, therefore, be inappropriate for many autistic young people [89]. Providing tailored sexuality education might enhance autistic young people’s social functioning development and, thus, help them build healthy romantic relationships [54, 90]. The curriculums could be enhanced by the use of technology in teaching (e.g., video vignettes), which could depict realistic scenarios followed by discussions of appropriate behaviors in response to those scenarios [91]. Incorporating an aspect of being aware of one’s internal sexuality (i.e., one’s own thoughts, feelings, and sensations) and being able to accurately recognize signals from others (which sometimes might not be intuitive to some autistic individuals), as well as acknowledging and normalizing low desire for partnered sexual activity that some autistic individuals present into sexuality education for autistic people might also be useful [17].

Due to the sensitivity of the topics, cultural aspects, values, and beliefs should also be considered, thus sexuality education should be developed with the collaboration of families [92]. Healthcare professionals could support parents in their understanding of autism and sexuality and thus enable them to discuss sex-related topics with their autistic children [47, 89, 93]. They could also encourage parents to discuss uncomfortable, albeit vital, topics with their autistic children, even if parents may deem them irrelevant to their children [92]. Educators should ensure that the programs include topics such as STDs, gender manifestation, and the diversity of sexual orientation [93]. Sexuality education ought to be provided to autistic young people as the main subject in their social skills training, to minimize the probability of them facing challenges in their romantic and sexual relationships [90].

Given the poor outcomes of romantic relationships in many young people with ADHD, it is important that inclusive assessment of young people with ADHD also comprises inquiries into the essence of their romantic relationships and the obtained information might be useful for clinicians to help develop individualized strategies and possibly sex education curriculums, which might then help this young population reduce unsafe sexual behaviors and achieve better outcomes of their romantic relationships [61]. Given that inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity are correlated with reduced motivation for the maintenance of romantic relationships, specific programs were suggested for each category of ADHD characteristics. Since inattention characteristics may cause to endure relationship dissatisfaction, the programs could aim at providing strategies to help focus on the partner’s good qualities, as opposed to concentrating only on one’s interests and pursuing new relationships, to sustain the relationship. Hyperactivity-impulsivity, however, may cause failure to stay in the relationship, hence the programs may aim at teaching skills to help learn to avoid destructive or impulsive responses to the partner’s challenging behavior (e.g., applying discussion to solve the problems) [36]. Young individuals with elevated ADHD symptoms, additionally, may benefit from receiving support on communication and conflict resolution skills to improve their romantic relationship experiences [31].

Future Directions

Research on sexuality education in schools is required to help understand what techniques and instructions are used during the lessons and whether they are effective in teaching autistic people about sexuality [46]. Further investigation into the topic, in addition to providing young people’s and parental perspectives [36, 56], should also provide views from educators [60]. Young people, caregivers, educators, and clinicians should collaborate to provide optimized tools for sexuality education [82]. Research should also strive to assess parent–child discussions about sexuality and parental perceptions of their own competence to communicate about sexuality with their autistic children [89]. Research should be more sensitive to the requirements of autistic individuals to help achieve a more profound understanding of the challenges they may face, with the ultimate goal to shape policy in special education [57].

Future studies should also provide an exploration of the topic of romantic relationship experiences, and sexuality communication within the family in the autistic population in more depth [43]. Qualitative designs could better shed light on, for example, the nuances of delivery or content in sex education (e.g., talking/discussion via social stories, specific topics) [93]. Research is also recommended on autistic individuals’ behaviors in their romantic relationships, including female participants and comparison groups. The comparison group may help to elucidate what specific aspects related to sexuality in autistic individuals might require support for both young people and their caregivers [41].

Given the importance of improving prevention and interventions attempting to help reduce core characteristics of ADHD, since individuals with ADHD tend to be particularly vulnerable to experiencing physical violence in their romantic relationships [31], researchers should direct their efforts to understand how to empower this group of the population in their romantic relationships [31]. Research should also investigate romantic relationship experiences in young people with ADHD, including investigating gender differences in these experiences and comparing them to their TD peers to better understand the uniqueness of romantic relationships in individuals with ADHD [60].

Notably, caregivers’ and educators’ perspectives of romantic relationship experiences, as well as studies examining the topic of sexuality education in the young population with ADHD are non-existent in the current literature, therefore, these vital gaps necessitate addressing. Qualitative research on the topic in the young population with ADHD is also absent from the current literature, however, qualitative designs might better shed light on some aspects of romantic relationship experiences in this group of the population. Importantly, this review highlighted the non-existence of research on romantic relationship experiences and sexuality education in individuals with ASD co-occurring with ADHD, and, therefore, it is imperative to investigate this area.

Conclusion

This literature review highlights that many neurodivergent young individuals experience greater challenges in building and maintaining their romantic relationships than their TD peers. Despite these difficulties, many of them do not receive adequate support in the form of sexuality education. Although many caregivers realize the importance of teaching sexuality to their neurodivergent children, often they feel unprepared to discuss some sexual topics with them. Educators should collaborate with neurodivergent young people’s parents to help them promote positive techniques in sexuality education to ensure better outcomes in young people’s romantic lives [88]. Educators’ perspectives on the subject, however, are absent from the current body of knowledge. This review also emphasizes the non-existence of research on the topic in young people with ASD co-occurring with ADHD, however, these young people might have even greater difficulties with navigating their romantic relationships than their peers with a single (ASD or ADHD) condition. Providing formal sexuality education as essential support for them might, therefore, be critical.

References

Boisvert, S., Poulin, F., Dion, J.: Romantic relationships from adolescence to established adulthood. Emerg. Adulthood 11(4), 947–958 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968231174083

Paat, Y.F., Markham, C.: The roles of family factors and relationship dynamics on dating violence victimization and perpetration among college men and women in emerging adulthood. J. Interpers. Violence 34(1), 81–114 (2019)

O’Brien, H., Hendriks, J., Burns, S.: Teacher training organisations and their preparation of the pre-service teacher to deliver comprehensive sexuality education in the school setting: a systematic literature review. Sex Educ. 21(3), 284–303 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1792874

Herbert, A., Fraser, A., Howe, L.D., Szilassy, E., Barnes, M., Feder, G., et al.: Categories of intimate partner violence and abuse among young women and men: latent class analysis of psychological, physical, and sexual victimization and perpetration in a UK birth cohort. J. Interpers. Violence 38(1–2), NP931–NP954 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221087708

Mumford, E.A., Liu, W., Copp, J.E., Taylor, B.G., MacLean, K., Giordano, P.C.: Relationship dynamics and abusive interactions in a national sample of youth and young adults. J. Interpers. Violence 38(3–4), 3139–3164 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221104536

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C. (2013)

Rutter, M., Kim-Cohen, J., Maughan, B.: Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 47(3–4), 276–295 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01614.x

Zablotsky, B., Bramlett, M.D., Blumberg, S.J.: The co-occurrence of autism spectrum disorder in children with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 24(1), 94–103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717713638

Enner, S., Ahmad, S., Morse, A.M., Kothare, S.V.: Autism: considerations for transitions of care into adulthood. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 32(3), 446–452 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000882

Lord, C., McCauley, J.B., Pepa, L.A., Huerta, M., Pickles, A.: Work, living, and the pursuit of happiness: vocational and psychosocial outcomes for young adults with autism. Autism 24(7), 1691–1703 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320919246

Pallanti, S., Salerno, L.: Adult ADHD in other neurodevelopmental disorders. In: The Burden of Adult ADHD in Comorbid Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders, pp. 97–118. Springer, Cham (2020)

Sparrow, S.S., Cicchetti, D.V., Saulnier, C.A.: Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 3rd edn. Vineland-3, San Antonio (2016)

Jang, J., Matson, J.L., Williams, L.W., Tureck, K., Goldin, R.L., Cervantes, P.E.: Rates of comorbid symptoms in children with ASD, ADHD, and comorbid ASD and ADHD. Res. Dev. Disabil. 34(8), 2369–2378 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.04.021

Thomas, S., Sciberras, E., Lycett, K., Papadopoulos, N., Rinehart, N.: Physical functioning, emotional, and behavioral problems in children with ADHD and comorbid ASD: a cross-sectional study. J. Atten. Disord. 22(10), 1002–1007 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715587096

Antshel, K.M., Zhang-James, Y., Wagner, K.E., Ledesma, A., Faraone, S.V.: An update on the comorbidity of ADHD and ASD: a focus on clinical management. Expert Rev. Neurother. 16(3), 279–293 (2016)

Mikami, A.Y., Miller, M., Lerner, M.D.: Social functioning in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: transdiagnostic commonalities and differences. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 68, 54–70 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.12.005

Bush, H.H.: Dimensions of sexuality among young women, with and without autism, with predominantly sexual minority identities. Sex. Disabil. 37(2), 275–292 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-9532-1

Cheak-Zamora, N.C., Teti, M., Maurer-Batjer, A., O’Connor, K.V., Randolph, J.K.: Sexual and relationship interest, knowledge, and experiences among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Arch. Sex. Behav. 48(8), 2605–2615 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1445-2

Gilmour, L., Schalomon, P.M., Smith, V.: Sexuality in a community-based sample of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 6(1), 313–318 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.06.003

Mehzabin, P., Stokes, M.A.: Self-assessed sexuality in young adults with high-functioning autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 5(1), 614–621 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.07.006

Gougeon, N.A.: Sexuality education for students with intellectual disabilities, a critical pedagogical approach: outing the ignored curriculum. Sex Educ. 9(3), 277–291 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810903059094

Hancock, G.I., Stokes, M.A., Mesibov, G.B.: Socio-sexual functioning in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses of existing literature. Autism Res. 10(11), 1823–1833 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1831

Joyal, C.C., Carpentier, J., McKinnon, S., Normand, C.L., Poulin, M.H.: Sexual knowledge, desires, and experience of adolescents and young adults with an autism spectrum disorder: an exploratory study. Front. Psychiatry 12, 685256 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.685256

MacKenzie, A.: Prejudicial stereotypes and testimonial injustice: autism, sexuality and sex education. Int. J. Educ. Res. 89, 110–118 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.10.007

Stanojević, Č, Neimeyer, T., Piatt, J.: The complexities of sexual health among adolescents living with autism spectrum disorder. Sex. Disabil. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09651-2

Sevlever, M., Roth, M.E., Gillis, J.M.: Sexual abuse and offending in autism spectrum disorders. Sex. Disabil. 31(2), 189–200 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-013-9286-8

Weir, E., Allison, C., Baron-Cohen, S.: The sexual health, orientation, and activity of autistic adolescents and adults. Autism Res. 14(11), 2342–2354 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2604

Wymbs, B.T., Canu, W.H., Sacchetti, G.M., Ranson, L.M.: Adult ADHD and romantic relationships: what we know and what we can do to help. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 00, 1–18 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12475

Babinski, D.E., Pelham, W.E., Jr., Molina, B.S., Gnagy, E.M., Waschbusch, D.A., Yu, J., et al.: Late adolescent and young adult outcomes of girls diagnosed with ADHD in childhood: an exploratory investigation. J. Atten. Disord. 15(3), 204–214 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054710361586

Canu, W.H., Carlson, G.L.: Differences in heterosocial behavior and outcomes of ADHD-symptomatic subtypes in a college sample. J. Atten. Disord. 6(3), 123–133 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1177/108705470300600304

Guendelman, M.D., Ahmad, S., Meza, J.I., Owens, E.B., Hinshaw, S.P.: Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder predicts intimate partner victimization in young women. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 44(1), 155–166 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9984-z

Friedman, S.R., Rapport, L.J., Lumley, M., Tzelepis, A., VanVoorhis, A., Stettner, L., Kakaati, L.: Aspects of social and emotional competence in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology 17(1), 50–58 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.17.1.50

Wymbs, B.T., Dawson, A.E., Egan, T.E., Sacchetti, G.M.: Rates of intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization among adults with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 23(9), 949–958 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716653215

Barkley, R.A.: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Guilford Publications, New York (2006)

Wymbs, B., Molina, B., Pelham, W., Cheong, J., Gnagy, E., Belendiuk, K., Walther, C., Babinski, D., Waschbusch, D.: Risk of intimate partner violence among young adult males with childhood ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 16(5), 373–383 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054710389987

VanderDrift, L.E., Antshel, K.M., Olszewski, A.K.: Inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity: their detrimental effect on romantic relationship maintenance. J. Atten. Disord. 23(9), 985–994 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717707043

Bush, H.H., Williams, L.W., Mendes, E.: Brief report: asexuality and young women on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51(2), 725–733 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04565-6

Dewinter, J., Vermeiren, R.R.J.M., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Van Nieuwenhuizen, C.: Parental awareness of sexual experience in adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46(2), 713–719 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2622-3

Dewinter, J., Vermeiren, R.R.J.M., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Van Nieuwenhuizen, C.: Adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorder growing up: follow-up of self-reported sexual experience. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 25(9), 969–978 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0816-7

Dewinter, J., Vermeiren, R., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Lobbestael, J., Van Nieuwenhuizen, C.: Sexuality in adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorder: self-reported behaviours and attitudes. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45(3), 731–741 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2226-3

Fernandes, L.C., Gillberg, C.I., Cederlund, M., Hagberg, B., Gillberg, C., Billstedt, E.: Aspects of sexuality in adolescents and adults diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders in childhood. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46(9), 3155–3165 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2855-9

Hancock, G.I., Stokes, M.A., Mesibov, G.B.: Romantic experiences for individuals with an autism spectrum disorder. Sex. Disabil. 38(4), 231–245 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-019-09573-8

Hartmann, K., Urbano, M.R., Raffaele, C.T., Qualls, L.R., Williams, T.V., Warren, C., et al.: Sexuality in the autism spectrum study (SASS): reports from young adults and parents. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49(9), 3638–3655 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04077-y

Holmes, L.G., Himle, M.B., Strassberg, D.S.: Parental sexuality-related concerns for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and average or above IQ. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 21, 84–93 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.10.001

Holmes, L.G., Shattuck, P.T., Nilssen, A.R., Strassberg, D.S., Himle, M.B.: Sexual and reproductive health service utilization and sexuality for teens on the autism spectrum. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 41(9), 667–679 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000838

Holmes, L.G., Strassberg, D.S., Himle, M.B.: Family sexuality communication for adolescent girls on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49(6), 2403–2416 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03904-6

Kenny, M.C., Crocco, C., Long, H.: Parents’ plans to communicate about sexuality and child sexual abuse with their children with autism spectrum disorder. Sex. Disabil. 39, 357–375 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09636-1

Kotzé, C., Fourie, L., Van der Westhuizen, D.: Clinical and demographic factors associated with sexual behaviour in children with autism spectrum disorders. S. Afr. J. Psychiatr. 23(1), 1–7 (2017)

May, T., Pang, K.C., Williams, K.: Brief report: sexual attraction and relationships in adolescents with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47(6), 1910–1916 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3092-6

Pecora, L.A., Hancock, G.I., Mesibov, G.B., Stokes, M.A.: Characterising the sexuality and sexual experiences of autistic females. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49(12), 4834–4846 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04204-9

Visser, K., Greaves-Lord, K., Tick, N.T., Verhulst, F.C., Maras, A., van der Vegt, E.J.: An exploration of the judgement of sexual situations by adolescents with autism spectrum disorders versus typically developing adolescents. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 36, 35–43 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2017.01.004

Brilhante, A.V.M., Filgueira, L.M.D.A., Lopes, S.V.M.U., Vilar, N.B.S., Nóbrega, L.R.M., Pouchain, A.J.M.V., Sucupira, L.C.G.: “I am not a blue angel”: sexuality from the perspective of autistic adolescentes. Cien. Saude Colet. 26(2), 417–423 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232021262.40792020

Dewinter, J., De Graaf, H., Begeer, S.: Sexual orientation, gender identity, and romantic relationships in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47(9), 2927–2934 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3199-9

Mackin, M.L., Loew, N., Gonzalez, A., Tykol, H., Christensen, T.: Parent perceptions of sexual education needs for their children with autism. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 31(6), 608–618 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.07.003

Masoudi, M., Maasoumi, R., Effatpanah, M., Bragazzi, N.L., Montazeri, A.: Exploring experiences of psychological distress among Iranian parents in dealing with the sexual behaviors of their children with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative study. J. Med. Life 15(1), 26–33 (2022). https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2021-0290

Teti, M., Cheak-Zamora, N., Bauerband, L.A., Maurer-Batjer, A.: A qualitative comparison of caregiver and youth with autism perceptions of sexuality and relationship experiences. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 40(1), 12–19 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000620

Hannah, L.A., Stagg, S.D.: Experiences of sex education and sexual awareness in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46(12), 3678–3687 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2906-2

Palermo, M.T., Bogaerts, S.: Sex selling and autism spectrum disorder: impaired capacity, free enterprise, or sexual victimization? J. Forensic Psychol. Pract. 15(4), 363–382 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/15228932.2015.1053557

Halkett, A., Hinshaw, S.P.: Initial engagement in oral sex and sexual intercourse among adolescent girls with and without childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archiv. Sex Behav. 50(1), 181–190 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01733-8

Margherio, S.M., Capps, E.R., Monopoli, J.W., Evans, S.W., Hernandez-Rodriguez, M., Owens, J.S., DuPaul, G.J.: Romantic relationships and sexual behavior among adolescents with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 25(10), 1466–1478 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054720914371

Rokeach, A., Wiener, J.: The romantic relationships of adolescents with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 22(1), 35–45 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054714538660

Avni, E., Ben-Itzchak, E., Zachor, D.A.: The presence of comorbid ADHD and anxiety symptoms in autism spectrum disorder: clinical presentation and predictors. Front. Psychiatry 9(717), 1–12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00717

Llanes, E., Blacher, J., Stavropoulos, K., Eisenhower, A.: Parent and teacher reports of comorbid anxiety and ADHD symptoms in children with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50(5), 1520–1531 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3701-z

Engström, I., Ekström, L., Emilsson, B.: Psychosocial functioning in a group of Swedish adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Autism 7(1), 99–110 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361303007001008

Hofvander, B., Delorme, R., Chaste, P., Nydén, A., Wentz, E., Ståhlberg, O., Herbrecht, E., Stopin, A., Anckarsäter, H., Gillberg, C., Råstam, M.: Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry 9(35), 1–9 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-9-35

Howlin, P., Moss, P.: Adults with autism spectrum disorders. Can. J. Psychiatry 57(5), 275–283 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700502

Pecora, L.A., Hancock, G.I., Hooley, M., Demmer, D.H., Attwood, T., Mesibov, G.B., Stokes, M.A.: Gender identity, sexual orientation and adverse sexual experiences in autistic females. Mol. Autism 11(1), 1–16 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-020-00363-0

Gray, S., Kirby, A.V., Graham Holmes, L.: Autistic narratives of sensory features, sexuality, and relationships. Autism Adulthood 3(3), 238–246 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0049

Parchomiuk, M.: Sexuality of persons with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD). Sex. Disabil. 37(2), 259–274 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-9534-z

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G.: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 151(4), 264–269 (2009). https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Cantor, D., Fisher, B., Chibnall, S.H., Townsend, R., Lee, H., Thomas, G., et al.: Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct. University of Virginia_2015_climate_final_report.pdf (2015). Accessed 11 October 2021

Kolta, B., Rossi, G.: Paraphilic disorder in a male patient with autism spectrum disorder: incidence or coincidence. Cureus 10(5), e2639 (2018). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2639

Kellaher, D.C.: Sexual behavior and autism spectrum disorders: an update and discussion. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 17(4), 562–562 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0562-4

Griffiths, D., Hingsburger, D., Hoath, J., Ioannou, S.: ‘Counterfeit deviance’ revisited. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 26(5), 471–480 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12034

Ballan, M.S.: Parental perspectives of communication about sexuality in families of children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Copiar. 42(5), 676–684 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1293-y

Holmes, L.G., Himle, M.B., Sewell, K.K., Carbone, P.S., Strassberg, D.S., Murphy, N.A.: Addressing sexuality in youth with autism spectrum disorders: current pediatric practices and barriers. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 35(3), 172–178 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000030

Burleson, B.R., Denton, W.H.: A new look at similarity and attraction in marriage: similarities in social-cognitive and communication skills as predictors of attraction and satisfaction. Commun. Monogr. 59(3), 268–287 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759209376269

Liu, J., Ilmarinen, V.J.: Core self-evaluation moderates distinctive similarity preference in ideal partner’s personality. J. Res. Pers. 84, 103899 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103899

Overbey, G.A., Snell, W.E., Jr., Callis, K.E.: Subclinical ADHD, stress, and coping in romantic relationships of university students. J. Atten. Disord. 15(1), 67–78 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054709347257

Barkley, R.A., Fischer, M., Smallish, L., Fletcher, K.: Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 45(2), 192–202 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2

Flory, K., Molina, B.S., Pelham, W.E., Jr., Gnagy, E., Smith, B.: Childhood ADHD predicts risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 35(4), 571–577 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_8

Galéra, C., Messiah, A., Melchior, M., Chastang, J.F., Encrenaz, G., Lagarde, E., et al.: Disruptive behaviors and early sexual intercourse: the GAZEL youth study. Psychiatry Res. 177(3), 361–363 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.009

Hosain, G.M., Berenson, A.B., Tennen, H., Bauer, L.O., Wu, Z.H.: Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and risky sexual behavior in young adult women. J. Women’s Health 21(4), 463–468 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2825

Ben-Naim, S., Marom, I., Krashin, M., Gifter, B., Arad, K.: Life with a partner with ADHD: the moderating role of intimacy. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26(5), 1365–1373 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0653-9

Jabalkandi, S., Raisi, F., Shahrivar, Z., Mohammadi, A., Meysamie, A., Firoozikhojastefar, R., Irani, F.: A study on sexual functioning in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 56(3), 642–648 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12480

Wymbs, B.T., Gidycz, C.A.: Examining link between childhood ADHD and sexual assault victimization. J. Atten. Disord. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054720923750

Blankenship, R., Laaser, M.: Sexual addiction and ADHD: Is there a connection? Sex. Addict. Compulsivity 11(1–2), 7–20 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/10720160490458184

Ballan, M.S., Freyer, M.B.: Autism spectrum disorder, adolescence, and sexuality education: suggested interventions for mental health professionals. Sex. Disabil. 35(2), 261–273 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9477-9

Corona, L.L., Fox, S.A., Christodulu, K.V., Worlock, J.A.: Providing education on sexuality and relationships to adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and their parents. Sex. Disabil. 34(2), 199–214 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-015-9424-6

Plexousakis, S., Georgiadi, M., Halkiopoulos, C., Gkintoni, E., Kourkoutas, E., Roumeliotou, V.: Enhancing sexual awareness in children with autism spectrum disorder: a case study report. In: Cases on Teaching Sexuality Education to Individuals with Autism, pp. 79–98. IGI Global (2020).

Rothman, E.F., Bair-Merritt, M., Broder-Fingert, S.: A feasibility test of an online class to prevent dating violence for autistic youth: a brief report. J. Fam. Violence 36(4), 503–509 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00194-w

Pugliese, C.E., Ratto, A.B., Granader, Y., Dudley, K.M., Bowen, A., Baker, C., Anthony, L.G.: Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a parent-mediated sexual education curriculum for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 24(1), 64–79 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319842978

Holmes, L.G., Strassberg, D.S., Himle, M.B.: Family sexuality communication: parent report for autistic young adults versus a comparison group. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50(8), 3018–3031 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04398-3

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., et al.: The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (2021). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., Lord, C.: Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) manual. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles, CA (2003)

Achenbach, T.M.: Manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile. University Associates in Psychiatry, Burlington (1991)

Kessler, R.C., Adler, L., Ames, M., Demler, O., Faraone, S., Hiripi, E.V.A., Howes, M.J., Jin, R., Secnik, K., Spencer, T., Ustun, T.B.: The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scalefor use in the general population. Psychol. Med. 35(2), 245–256 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704002892

Conners, C.K.: Conners-3, 3rd edn. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (2008)

DuPaul, G.J., Reid, R., Anastopoulos, A.D., Lambert, M.C., Watkins, M.W., Power, T.J.: Parent and teacherratings of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: factor structure and normative data. Psychol. Assess. 28(2), 214–225 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000166

Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Lucas, C.P., Dulcan, M.K., Schwab-Stone, M.E.: NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule forChildren, Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some commondiagnoses. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 39(1), 28–38 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014

Swanson, J.M.: School-based assessments and interventions for ADD students. K. C. Press, Irvine (1992)

Lord, C., Rutter, M., Goode, S., Heemsbergen, J., Jordan, H., Mawhood, L., Schopler, E.: Autism diagnostic observation schedule. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1037/t54175-000

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P.C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., Bishop, S.L.: Ados. Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Manual. Los Angeles, WPS (1999)

Allison, C., Auyeung, B., Baron-Cohen, S.: Toward brief “red flags” for autism screening: the short autism spectrum quotient and the short quantitative checklist in 1,000 cases and 3,000 controls. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 51(2), 202–212 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.11.003

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., Clubley, E.: The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, malesand females, scientists and mathematicians. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 31, 5–17 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005653411471

Baron-Cohen, S., Hoekstra, R.A., Knickmeyer, R., Wheelwright, S.: The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ)—adolescent version. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 36, 343–350 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0073-6

Gillberg, C., Gillberg, C., Råstam, M., Wentz, E.: The Asperger Syndrome (and high-functioning autism) Diagnostic Interview (ASDI): a preliminary study of a new structured clinical interview. Autism 5(1), 57–66 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361301005001006

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MS and CSA screened all articles returned in the database search for inclusion in the review. CSA and AB provided support and feedback to MS during the initial database search phase and during the draft writing stage. All authors reviewed and approved the final revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smusz, M., Allely, C.S. & Bidgood, A. Broad Perspectives of the Experience of Romantic Relationships and Sexual Education in Neurodivergent Adolescents and Young Adults. Sex Disabil 42, 459–499 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-024-09840-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-024-09840-3