Abstract

Current research in attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with intellectual disabilities yields heterogeneous results. The aim of the present paper was to systematically review current qualitative and quantitative evidence of attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with intellectual disabilities. A systematic review of current literature (2000–2020) was carried out in the ERIC, PsychINFO, SCOPUS, PUBMED, and WebOfScience databases. Thirty-three articles were included for review. The present review protocol is registered in the PROSPERO database. Included studies presented attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with intellectual disabilities in samples comprised of staff, family, members of the community, and adults with intellectual disability. Community samples held more positive attitudes, followed by staff and family. Adults with intellectual disabilities reported interest in intimate relationships but perceived barriers in others’ attitudes. Factors such as familiarity, age, gender of the adult with a disability, and culture seemed to have clear relationships. Other factors such as gender or social status remain unclear. In general, attitudes were considered positive. However, a preference for low intimacy and friendship or Platonic relationships was found. Stereotypes towards intellectual disability may have a strong influence. These findings underline the need to investigate and address attitudinal changes to provide adequate support for adults with intellectual disabilities in regard to a healthy relational and sex life.

Prospero registration number: CRD42021222918.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introductions

Sexuality and its expression are one of human beings’ principal rights. To date, they are considered an integral part of adult life [1]. However, when considering a population of people with disabilities, sexuality remains quite stigmatized [2]. In the case of adults with intellectual disabilities (ID), the expression of their sexuality has been denied for a long time [3]. Only recently the sexuality of adults with ID has began to interest researchers [4]. This seems to occur following current changes in disability paradigms and movements. As a basic human need, sexuality cannot be separated from quality of life and life satisfaction [5], which is reflected in the latest work paradigms that strive to achieve the highest level of quality of life and full inclusion for the adult with ID [6]. However, and despite this focus on quality of life and inclusion, we still know little about sexuality and ID [7].

Adults with ID are often discouraged from exploring and developing their sexuality [5], given the common overprotective attitudes that exist. This could be expected, as adults with ID are considered to need protection, given that their cognitive impairment interferes with informed decisions [8]. Also, overprotective attitudes may be influenced by the fact that adults with ID have been labeled as asexual [3]. The latter contradicts reality. According to empirical studies, most adults with mild/moderate ID would engage in sexual relationships and are interested in sexuality [9, 10]. Adults with ID have significantly less knowledge about sexuality than their nondisabled peers and present more misunderstandings about sexual issues [11]. An intimate life without adequate knowledge and support could lead to unsatisfactory or harmful sexual or intimate interactions.

The lack of knowledge and support may be highly influenced by other people’s attitudes and behaviors towards the sexuality of adults with ID. Attitudes of related persons (staff, family) have been shown to be key to the information received by adults with ID, and such attitudes also seem to depend on general community attitudes [1]. Furthermore, attitudes towards these people’s sexuality have significant effects on their sexual decision-making and self-perception [4, 5]. When inappropriate, the attitudes of others can even have traumatizing effects [12]. Considering these findings, we need to examine different populations’ attitudes and how different factors influence positive or negative perspectives. This would help develop adequate interventions, programs and/or campaigns to change attitudes. A deeper understanding about these attitudes would provide empirical evidence to support adults with ID, their families, and different services or facilities’ staff. This should be the first step, as it is necessary to raise people’s awareness before training them to support adults with ID to achieve a healthy intimate life and to manage sexual behaviors (either alone or with a partner).

To date, some studies have examined the sexuality and/or attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with ID with heterogeneous results. Some review papers have tried to collect information about attitudes towards different aspects of the sexuality of adults with ID in specific samples [13, 14]. However, no reviews were systematic. The review carried out by Aunos et al. [13] stated that the reported results could be outdated. Furthermore, the study carried out by Futcher [14] only included four studies of family and staff samples, providing a very narrow overview and without reaching conclusions that could be generalized in a broad manner. Other reviews report an indirect perspective through the analysis of barriers, experiences, or support [4, 5, 7, 15]. A very recent review of public opinions [16] was found, which offers a general overview of quantitative studies. This last study stated that further empirical research was needed, as relevant articles and reports in the field could have been missed by the review (e.g., studies with ID populations or studies assessing attitudes that were not considered as part of the public opinion on sexuality). The present paper provides an in-depth and complete systematic review of current qualitative and quantitative evidence on attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with ID (including the views of the adults with ID themselves). It focuses on a broad population and related factors and addresses different areas of the sexuality of adults with ID. Relevant information to the research field and some strong conclusions are also provided.

Therefore, the aim of this paper is to synthesize current qualitative and quantitative evidence in attitudes towards the intimacy and sexuality of adults with ID. To assess these attitudes, the main research question is: what are the current attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with intellectual disabilities? To completely respond to this question, the following sub-questions should be answered:

- Q1::

-

What attitudes are held by different groups (services staff, parents, general population)? How do they differ?

- Q2::

-

What are the attitudes towards sexuality in people with ID? Do these attitudes differ from the general population’s attitudes or expectations?

- Q3::

-

Which sociodemographic and/or cognitive factors could relate to negative or positive attitudes?

Methods

The current review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA-P) tool [17] and reported in line with the PRISMA guidelines [18] recommendations. On December 10, 2020, our systematic review protocol was submitted on the PROSPERO database, being finally registered on January 10, 2021. PROSPERO is an international database for systematic reviews, which aims to avoid duplication and reduce reporting bias.

Search Strategy

Initial search and reference retrieval was conducted by one author in December 2020 through the following databases: PubMed, Scopus-Elsevier, WebOfScience, Education Resource Information Centre (ERIC), and PsycInfo. Search terms were introduced in Boolean search as follows: ((attitudes AND sexuality) AND (((intellectual OR learning) AND disabilit*) OR (mental AND retardation))). Search results were limited to those published between January 2000 and December 2020. When possible, search strategy was limited to include these terms in the title, keywords, and/or abstract information.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The three authors agreed on the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. These are as follows: (a) empirical quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods studies, (b) written in English and from peer-reviewed academic journals, (c) published between January 2000 and December 2020 (in order to include current attitudes towards the issue) and (d) assessing attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with intellectual disabilities. Exclusion criteria included studies with a focus on: (a) attitudes towards the sexuality of people with mental or physical disabilities only, (b) attitudes towards parenthood, contraception and/or sexual orientation without assessing general attitudes towards sexuality in adults with ID, (c) attitudes towards couple relationships, without assessing sexuality issues, (d) sexuality related experiences and/or opinions without explicitly assessing attitudes or attitudinal systems, (e) attitudes and sexuality of adults with an autism spectrum disorder, and (f) attitudes towards the sexuality of adolescents with ID.

Data Extraction

A codebook was developed to gather main characteristics and information about all the eligible full-text downloaded studies. Initially, it included information about study ID, type of study, sample type, sample size, sample age, instruments/measures, data analysis, review question(s) answered, main results, observations and exclusion criteria—if any. Eight articles were coded during a pilot test. During this process, minor changes were addressed; sample age was eliminated and country, study hypotheses/sub-questions, and main limitations were added to the original codebook. No study was excluded after this process.

In order to extract all the relevant information and data from the included reports, and facilitate the data synthesis process, a complete data extraction sheet was developed. This included more in depth and classified information from the selected studies. This instrument was based on the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group Data Extraction Template for Included Studies [19]. Initially, it was applied to eight randomly selected studies to assess suitability to our data extraction needs and refined accordingly.

Quality Assessment

First, minimum quality standards were expected by including only journal articles that had been published in academic peer-reviewed journals. However, as a secondary quality assessment measure, the mixed-methods appraisal tool (MMAT) was used [20]. The MMAT consists of five different checklists (one for each study type, including qualitative research, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies and mixed-methods studies). The election of this tool was based on its scope, given that it allows quality assessment for the three types of studies included in the present paper (qualitative, quantitative descriptive, and mixed-methods) with the same tool criteria. For each type of study, five questions that address quality of the study must be filled out, in order to evaluate if the information has been reported adequately (to be filled out with yes, no, can’t tell). According to the authors’ recommendations, an overall score is discouraged in favor of a more detailed presentation. Papers were not excluded according to the results of their critical appraisal (Table 1).

Results

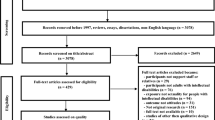

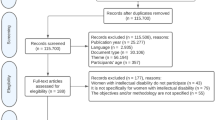

The initial literature search yielded 729 records (85 ERIC, 183 PSYCINFO, 134 PUBMED, 152 SCOPUS, and 175 WEB OF SCIENCE). After duplicates had been removed, 447 references were left. Once filtered by journal papers, 364 journal papers were screened for eligibility by title and abstract.

On a first title-abstract review, 265 articles were excluded. This led to a total number of 99 papers potentially eligible for inclusion. From these, 24 papers were excluded as they assessed different experiences surrounding sexuality in people with ID but not attitudes towards their sexuality. Two papers assessed general attitudes towards people with ID. Twenty addressed attitudes towards parenthood, marriage, sex education, contraception or similar without assessing direct attitudes towards the sexuality of people with ID (including sexual relationships or sexual rights), to be eligible for the present review.

Finally, 53 papers were fully downloaded for further examination and eligibility determination. From these, one article was exclude because of language. Five were scale validation articles. One did not exactly assess attitudes towards sexuality of people with ID. Four assessed beliefs and/or perceptions without assessing attitudes or attitudinal systems. Six assessed attitudes in adolescents or mixed data from adolescents with young people. Two assessed only attitudes towards physical disabilities and two only assessed attitudes towards couple relationships among adults with ID but not sexuality. Additionally, four papers were manually reviewed after screening the references of the included studies. One met the inclusion criteria [21]. Finally, 33 articles were proposed for inclusion in the present review. The flowchart is available in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the Reviewed Studies

A total of 33 articles were included for review. These included adults with ID [22, 23], family [24], staff [21, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], and community [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] samples. Other studies examined differences among groups, including family versus staff. versus community samples [45,46,47,48], family versus staff samples [49] and staff versus community samples [50, 51]. Two studies included different samples but did not separate groups for analysis [52, 53]. In regard to methodology, the majority of the included studies were comprised of quantitative studies [21, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48, 50, 51, 53]. Three studies employed mixed-methods methodologies [22, 49, 52] and two were based on qualitative methodologies [32, 33].

Different attitudinal measures were used across studies. Twelve studies used the ASQ-ID questionnaire. Three [34, 38, 46] used a preliminary version, proposed by Cuskelly and Bryde [46], while eight [27, 29, 35, 44, 47, 48, 50, 53] used the final version proposed by Cuskelly and Gilmore [1]. One study [22] generated an easy-to-read adaptation for use in adults with ID. Other scales that were used were the SMRAI [25], the POS [31, 34], the GSAQ-LD in its general [39] and parent [24] versions, and the SAQ [26]. Seven studies employed self-constructed Likert-type questionnaires [21, 30, 37, 40, 43, 49, 51]. Two completed questionnaire data with case scenarios [21, 49]. One study employed a self-constructed interview questionnaire with visual support [23]. Two studies used self-generated semantic differentials scales [28, 43]. One study self-generated a questionnaire based on a Q-methodology technique [52]. Semistructured self-generated interviews were carried out in qualitative studies [32, 33], and a mixed-methods study gathered information from interviews of a broader study [41]. Sixty-four case scenarios assessing acceptability, generated by Esterle et al. [36], were used in three studies [36, 42, 45].

Studies were carried out across different geographical regions. These included USA [21, 29, 31, 35, 51, 52], Australia [27, 38, 46, 50], United Kingdom [26, 32, 33, 44], Ireland [30, 41, 49], Taiwan [22, 48], France [36, 42], Mexico [42, 45], Greece [24, 39], Poland [28, 43], Italy [25], Portugal [37], Israel [40], Canada [34], Netherlands [23], Serbia [47], and Indonesia [53]. Geographic region, study aim, sample characteristics, data collection instruments, and main findings, are available in Table 2.

Attitudes Towards Sexuality Described by Adults with ID

Two studies assessed attitudes towards sexuality in a population with mild-moderate intellectual disability [22, 23]. Both studies concluded that people with intellectual disabilities are interested in sexuality issues and have had some kind of experience. Siebelink et al. [23] found positive attitudes towards kissing, hugging, and sexual intercourse. Chou et al. [22] exposed explicit manifestations of adults with ID of being interested in intimate relationships but not knowing how to engage. Disagreement with how society and law treats sexuality issues in adults with ID was explicitly manifested by them [22].

Gender differences were also found: women and men held similar attitudes except for masturbation, adult movies, and prostitution, with more negative attitudes in women [23]. When examining attitudes with an easy-to-read version of the ASQ-ID in Taiwan, more differences appeared. Both women and men held similar attitudes towards their sexual rights and sexual self-control ability, but women were more negative towards non-reproductive sexual behaviors and parenting capacity, and expressed more negative experiences [22].

Opportunities to develop intimate relationships are described by adults with ID as limited [22]. Attitudes of people with ID were positively related to their own sexual experience and needs [23], and self-perceived as highly related to parents, related people, and society expectations and attitudes [22]. Explicit examples of the latter are adults with ID verbalizations such as: “This is a very private issue. Parents do not talk about it or let us know about it”; “I cannot talk about masturbation, otherwise I will be punished … Masturbation is not a healthy behavior”; “a man and a woman cannot get physically close to each other … my mom says I’m not capable of taking care of myself”; and other verbalizations about having to get permission to have a boyfriend or girlfriend, a relationship and similar; and having to stick to the residential center normative [22].

Family Attitudes Towards the Sexuality of Adults with ID

Almost all studies including family member attitudes were carried out in comparison with other population groups [45,46,47,48,49], with the exception of one study, which was only comprised of a parent sample [24]. These studies reflected moderate to accepting attitudes towards sexuality of adults with ID [24, 45,46,47], including explicit desires of sexuality of people with ID being acknowledged [49]. On the contrary, one study carried out in Taiwan concluded that the attitudes of parents were negative, especially when it comes to their own child’s sexual and parenting rights [48].

In general, attitudes become less positive in regards to parenting [46, 47], with one study finding slightly more positive attitudes in men with ID than in women [48]. When described, attitudes were less positive for same-gender sexual behaviors [24]. One study reports that parents held more positive attitudes towards men with ID in self-controlling their sex drive (versus women) [47]. When considering their own child’s disability severity or age, attitudes remain similar [46]. However, when comparing parental attitudes when having children with Down syndrome and neuromotor disorders, parents of people with Down syndrome showed significantly more positive attitudes [45]. When compared with parent samples, siblings were more supportive and open to talk about sexuality issues with their relatives [49]. The main concerns included protection from abuse and a need for constant supervision [49]. Parents and siblings preferred preventive interventions when it came to sexuality-related scenarios, with a preference for low intimacy levels and friendship or Platonic relationships [49].

Staff Attitudes Towards the Sexuality of People with ID

Studies assessing the attitudes of staff members consisted of different types of service providers or carers [21, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], and in some cases involved comparisons with family [49], community [50, 51] or both sample groups [45,46,47,48]. In general, attitudes towards the sexuality of people with ID in staff samples were positive [21, 27, 29, 30, 32, 46, 47, 50, 51], with some studies reporting moderate attitudes [25, 26, 28, 48] and one study reporting negative attitudes [33]. When comparing numbers, the majority of staff members tend to show acceptance of the sexuality of adults with ID [45]. When addressing desires, the importance of sexuality in one’s life, freedom, and the opportunity to experience their sexuality in women with ID, a high percentage of staff were supportive [21]. When differentiating by socio-sexual behaviors, staff members were positive towards behaviors of public displays of affection, private displays of affection,and safe sex but negative towards behaviors such as public kissing, anal sex, and risky sex [31]. The latter were also seen as inappropriate for the general population. Overall, the more negative attitudes were held towards parenting [46, 50], same-gender relationships [30,31,32,33, 51], one-night stands [30], self-control [47], and involvement of the person with ID in decisions regarding their own sexuality [32].

The type of service and job position was also related to attitudes. Compared to large nursing homes, staff in small residential community settings were more positive towards the adult with ID’s sexuality and sexual orientation [26]. Social service providers in outpatient services held the most positive attitudes in contrast to residential and day care center services [25]. The same went for the comparison between private/voluntary agencies (more negative) and school/social services (more positive) towards sex education [30]. Regarding job position or status in the agency, some studies found a relationship between responsibility or being in program management positions and more positive attitudes [27]. For this last study, this difference was replicated between instructors (more positive) and support workers. Social workers were also reported as more positive than special educators and paramedical professionals; special educators showed the lowest acceptance of sexual intercourse [28]. Those in management positions in residential services who had attended university versus those with same status and education in other services were less positive [25]. Social care officers and qualified nursing staff did not differ in their attitudes [26].

Studies suggest that these differences could be explained by the type of experience they have with people with ID, in terms of the probability of occurrence of some sexually-related behaviors [28] or of the level of functionality/severity [26, 28]. In turn, it could also be explained by how they have to deal with difficult situations less [25]. However, other studies did not find any relationship with status [30].

Staff carers demanded training in sexuality and ID for themselves, for service users and for family carers, as well as specific guidelines and policies [49]. For staff samples, training in sexuality and/or sexuality and ID related to more positive attitudes [30]. Knowledge about the topic is scarce but perceptions do exist. When examining attitudes towards women with ID, less than half of the staff participants felt other service providers recognized these women as sexual beings [21]. However, staff members defended that they were aware of the experience of sexuality of adults with ID [21, 32] and showed support for them engaging in intimate relationships [49]. Staff member testimonies maintain that “They understand sexuality in the same way that anybody else does” or “I think if you really think about this, it’s no different to the understanding that people without a learning disability have” [32].

General Population Attitudes Towards the Sexuality of Adults with ID

Studies comprising general population attitudes [36, 39, 41, 42, 44] or student samples as part of the general population [34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 43] show interesting results. This information can be extended when compared to staff [50, 51] and staff-community-parents comparisons [45,46,47,48]. In general, community samples held moderate [35, 36, 42] to positive [38, 39, 42, 44, 48, 50] attitudes. When compared to staff and family members, they seem to show the more positive attitudes [46,47,48]. Conversely, a study carried out in Israel found negative attitudes towards sexuality of people with ID in a student sample [40]. Some of these studies showed more positive attitudes towards parenting and sexual rights than for self-control and non-reproductive sexual behavior [35] while others did not support these attitudes towards parenting [38, 51]. People seem to be more worried about the sexual relationship consequences rather than the intercourse per se [36]. The main concerns involve consent and vulnerability to abuse [41].

Studies in student samples found a relationship between the type of studies and attitudes [37, 38]. When comparing students majoring in architecture, medicine and psychology, architecture students held the more negative attitudes, while psychology students were the most supportive [37]. This last study also found that training year in medicine (sixth versus first year) and enrollment in a sexuality subject in psychology related to more positive attitudes. This happens in a similar way with students with experience in support work; the more advanced in their educational/psychology studies, the more positive [34]. When comparing disability, midwifery and education students, disability students were more positive towards parenting and sterilization, with non-significant positive attitudes towards marriage and intercourse [38]. For student samples, positive attitudes towards affectivity and sexual life are reported. However, when referring to objective demonstrations, attitudes were more negative. Adults with ID were seen as more childish in their emotional relationships and less able to show self-control [37]. Students reported a tendency to consider sexuality and love in people with ID more positive when Platonic or as a friendship [43].

Comparison Between Groups

Studies compared attitudes towards the sexuality between different population groups comprised of parents, staff, and community (mostly students) samples [45,46,47,48], or parent versus caregiver samples [49]. One study compared staff and community staff samples (leisure staff) [50]; another compared young and old community samples versus direct care staff [51], and students with support worker experience and students without this experience [34].

In general, family members tend to express the more negative attitudes [46,47,48,49]. A study carried out in Taiwan found family members to be less positive towards parenting, sexual rights, non-reproductive sexual behavior, and self-control than community and staff samples (except for self-control in men, where family and staff members did not differ) [48]. By contrast, a study carried out in Mexico did not find differences between parents and staff attitudes, but did find significant differences comparing acceptability levels of parents of people with Down syndrome and neuromotor disorders, with more negative attitudes across the latter [45].

Staff members held, in general, more negative attitudes than community samples but more positive than parents [46,47,48] with exceptions and nuances [45, 51]. In comparison to family members, staff were more open to sexuality and relationships among adults with ID, and considered lack of training the main impediment [49]. On the contrary, one study found them to be less confident in regards to the ability of adults with ID to exert sexual self-control [47]. One study comparing attitudes in support workers and leisure staff did not find attitudinal differences, except for parenting; support workers were less supportive [50]. Another study reported similar attitudes towards socio-sexual behaviors of people with ID among young community people and direct care staff, and more negative attitudes among older community samples (dating, marrying, children) [51]. When examining student samples, experience in support working showed a tendency of more accepting attitudes [34]. Results should be interpreted with caution. When including some sociodemographic factors as control variables to multiple regressions models, those variables explained a significant proportion of variance with a large effect [48]. Age is proposed as the main related variable for the sample differences [46].

Factors Related to More Negative or Positive Attitudes

Different factors are expected to relate to more negative or positive attitudes. These comprised age, gender, gender of the person with ID, education and training, culture, familiarity with ID, social class, religiosity, authoritarianism (personality trait), and belief systems.

Across studies, age has been related to attitudes. Younger participants held more positive attitudes in samples comprised of staff [27, 31], family [24], community [36, 39, 51] and a combination of these three groups [46, 48]. A study with a student sample reported more positive attitudes towards parenting in the younger participants [38]. Another study reported this difference between the youngest (20- to 29-year-olds) and the 50 to 59-year-old group for sexual rights for women [27]. Other studies involving staff [26, 29, 30, 50], students with support work experience [34], community [44], and mixed samples [47, 53] did not find that relationship.

However, the effect of age seemed to be one of the most accepted. What is more, two studies reported that staff and/or community sample versus family sample differences would be explained by the age difference more than by sample precedence [46, 49]. A study comparing younger and older adults and direct care staff showed younger adults to be more positive than staff members, but older adults to be more negative than both [51]. Attitudes towards human sexuality and level of discrimination against the sexuality of people with ID also related to older age; a relationship in terms of discrimination was larger when unemployed [39]. When combined with gender in variance models, one study found that mothers between 20 and 50 years of age were the most supportive, and fathers over the age of 51 discriminated the most [24].

Gender influence seemed to remain unclear. In some studies, women staff members held more positive attitudes towards sexual rights and self-control [29]. So did female students towards sexual rights of people with ID [35] and the right to an emotional and sexual life, approaching the issue at home, and the possibility of marriage and sex education [37]. Others found male staff more supportive towards sexual education and parenting [30]. On the contrary, a study with staff and community samples found more negative attitudes in women populations, specifically in regard to sexual intercourse, parenting, marriage and petting; and men attitudes were more negative towards men kissing with a same-gender partner [51]. Finally, other studies did not find clear relationships between gender and attitudes in staff [26, 27], community [39, 44] or family-staff-community samples [46, 47, 53].

Some studies hypothesized that the gender of the adult with ID influences attitudes. One study found more positive attitudes for men, especially towards parenting in a parent group [48]. Another found the same relationship from parents in regard to self-control [47]. However, other studies comprising family, staff and community samples found the opposite relationship [48, 50]. Less sexual freedom has been reported to be accepted for women versus men [50]. Other studies in general population samples found more positive attitudes towards sexual rights, parenting, and non-reproductive sexual behavior for women with ID (versus men) [47]. A qualitative study in staff members suggested that gender differences would be fed by gender stereotypes such as men with ID being more sexually-driven and women with ID more sexually innocent and vulnerable [33]. For the latter, more male than female inappropriate scenarios were reported by the study participants. Two studies did not find direct differences in attitudes towards women and men with ID in staff samples [27, 47]. However, when examined in interaction with sociodemographic factors (such as age, position, and training) differences seem to appear; more positive attitudes towards women with ID were reported for sexual rights, non-reproductive sexual behavior, and self-control [27].

Some studies support the hypotheses that higher levels of education relate to more positive attitudes. This has been found in some staff [26], community [39], parent [24], and mixed samples [48]. This relationship remains unclear, as some other studies did not find that relationship [27, 29, 50]. These last studies however, associate more positive attitudes with specific training in the issue [27] or training in human sexuality [29]. Attending a human sexuality subject favored more positive attitudes in psychology students [37]. A specific lecture strategy for midwifery students did not contribute to significant changes in attitudes but did show a trend in attitudinal change [38]. A lack of knowledge about sexuality in ID and policies has been explicitly revealed [32] and there is a demand for training [49]. One study found a negative relationship between the educational level and attitudes but only for residential staff [25].

Studies found a variation in attitudes across cultures and cultural factors [35, 42, 44, 53]. An Indonesian study compared how attitudes, measured by the ASQ-ID, differed from attitudes reported in previous studies on different countries [53]. According to this last study, British White Westerners were the most positive, followed by British South Asians. Italian undergraduates and Americans were slightly less positive, and Indonesians were the most negative. A study comparing acceptability of sexual intercourse among French and Mexican participants reported higher acceptability among Mexican participants [42]. This study reported that Mexicans were more accepting of regular sexual intercourse between someone with ID and someone without a disability, and related it to Mexicans being a more collectivistic society versus the individualistic French society.

Cultural orientation has been found to be a strong predictor, with horizontal individualism and horizontal collectivism related to more positive attitudes and vertical individualism related to the more negative attitudes [35]. A comparison of White Westerners and South Asians living in the UK reported White Westerns to be more positive towards the sexual rights and sexual self-control of adults with ID [44]. The latter study hypothesized that South Asians would have had to accommodate to more positive Western attitudes. Comparing across regions, a study carried out in Ireland found more positive attitudes when living in rural Ireland than in Dublin city [41]. On the other hand, a study carried out in Greece did not find differences across participants living in Athens and two other Greek areas [39].

Being familiar with intellectual disabilities in terms of level of contact seemed to show a relationship. Some studies found a minor relationship between familiarity and attitudes towards parenting and sexual rights [35]. Others found that students with frequent contact with people with ID were less in favor of adults with ID having access to nude or semi-nude photographs; but defended the capacity of the adult with ID to take responsibility for his/her actions [37]. In other scenarios, contact with people with ID did not relate to attitudes [39, 44]. Staff members with an immediate family member with ID held more positive attitudes towards the ability of sexual self-control [29]. An interesting finding reported more positive attitudes and agreement to sexuality in adults with ID when reporting being comfortable with people with ID living in the neighborhood [41]. How intellectual disability is approached related to attitudes [43]. The latter reported that predominance of a social model of ID related to positive attitudes and normalization; while individual-biological explanations related to a more negative approach, the perception of the adult with ID as asexual, and sexuality as biologically determined.

Other factors have been examined, with less literature available. Social class did not relate to acknowledgement of the right to sexual expression of people with ID and sexual education in community samples [39], but it did in parent samples, with middle class respondents holding more positive attitudes than working class [24]. A study reported slightly more positive attitudes among those being single rather than married [41]. The latter study also reported that having larger social networks related to more positive attitudes. Religiosity and/or church attendance related to more negative attitudes in staff, especially towards same-gender relationships and one-night stands [30]. In terms of non-attendance, Christian, and Buddhist, those who declared themselves Buddhist held more negative attitudes [48]. Not having a religious affiliation in students with experience in support work related to more positive attitudes, and those identified as Jewish were more positive than those identified as Christian [34]. The level of authoritarianism (personality trait) related to more negative attitudes towards the sexuality of people with disabilities, without interaction with disability type (intellectual or paraplegia) [40].

Other studies explained acceptability of sexual intercourse according to different characteristics of the person with ID and setting and in interaction with demographic factors [36, 42, 45]. These studies proposed case scenarios in 64 vignettes. Interaction of factors such as autonomy level, contraception use, and partner’s characteristics (less strong) explained acceptability [36, 42]. The French study reported that, if led to procreation, the relationship would not be accepted [36]. When replicated in Mexico, participants attitudes were distributed in clusters of beliefs-attitudes [45]. They classified sexuality in adults with ID as “mainly acceptable”, “mainly unacceptable” or “depending on circumstances” [45]. Related to the latter, it is proposed that attitudes appear clustered in bigger belief systems, according to Q-methodologies [52]. This last study clustered belief systems in four groups: Humanists, Advocates, Supporters, and Regulators. Groups varied as a function of the consideration they have of the adult with ID having an intimate life, sex education, sterilization, and similar factors.

It is worth noting that some studies compared attitudes towards sexuality of adults with ID with attitudes towards sexuality of people with other disabilities [28, 40, 41]. Attitudes towards the sexuality of those with ID were more negative than for those with physical disabilities [28, 41] and paraplegia [40]. Although people tend to accept that adults with ID have a sexuality, the physical and psychosocial dimensions of that sexuality are differentially seen and accepted [28]. On the other hand, acceptance of sexuality in adults with ID was higher than for those with mental difficulties [41]. In a comparison of attitudes towards the sexuality of people with ID and people without disabilities, more negative attitudes were drawn for those with ID [31, 39, 50, 51]. One study comparing attitudes towards different sexual behaviors showed more negative attitudes towards public and private display of affection behaviors, safe sex, and risky sex (versus peers perception) but no difference towards anal sex, same sex partner, and prolonged public kissing [31].

Discussion

Sexuality is a right and an important part of adult life. The access to a healthy sexuality for adults with ID is strongly related to the attitudes of others towards their sexuality. Hence, the aim of the present study was to examine current attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with ID across different populations. Thirty-three peer-reviewed articles were identified. Adults with ID were interested in sexuality and intimacy issues, yet reported being influenced by the lack of support or attitudes of others. Furthermore, moderate to positive attitudes were found in family, staff, and community samples. Few studies reported negative attitudes. These studies mainly corresponded to studies carried out in cultures which already treat sexuality as a taboo subject. However, reality shows some incongruences. For example, across staff members, adults with ID are reported to be kept apart from each other and kissing or holding hands are discouraged when working in relationship programs [26]. Across student samples, positive attitudes are reported until it comes to objective demonstrations, where attitudes tend to be more negative [37].

Some of the included studies found preference for platonic and friendship relationships instead of romantic relationships, even when holding apparently positive attitudes. This ambivalence is not new. Previous studies confront sexual rights discourses and moral commitment to support sexuality of adults with ID, with voices of caution towards their sexuality [4]. This is congruent with findings across adults with ID in the present study: they manifest sexual desire and interest in intimate relationships, but note a main barrier in society and those around their life. Similar findings are observed in previous studies [7]. In addition, for the adult with ID, knowing more about sexuality correlates with more positive attitudes [23], and their knowledge depends on others. In general, sexuality of adults with ID would be limited by social norms, but also by added factors such as lack of privacy, dependency on others, and especially control of their sexual expression by others [5].

Different factors were significant in determining positive attitudes, while others remain unclear. How we relate to disability was determinant. Family members tend to show the less positive attitudes, led by staff members, and community samples. However, not only would the type of relationship affect attitudes, but in which way and how frequently people interact, and the type of scenarios they have to address. Staff findings reported that the type of service and, in some cases, the job position, related to more negative or positive attitudes; probably related to the type of related behavior they have to deal with and disability severity [26, 28]. How the degree of familiarity relates to attitudes could be considered unclear. Its relation to attitudes could depend more on the type of interaction and factors such as the ones previously mentioned, than on the level of familiarity. In general and as reported in previous studies [4], a lack of knowledge on how to treat sexuality in people with ID has been extensively found across samples. Clear policies and guidelines are needed [4, 15]. So is training, such as human sexuality training and type of studies related to more positive attitudes.

Across studies, older age was related to less positive attitudes and can be concluded to be one of the stronger related factors. This could be expected, as sexual behavior and attitudes in the general population reflects the same relationship, with more positive thoughts across millennial populations [54]. Differences mainly appear between older and younger participants. Previous studies expected attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with ID to have changed across decades [13] and age differences may be a reflection of society’s general attitudes in this regard. Studies that did not find differences were carried out among staff samples, and/or the majority of the participants were young or middle-aged and/or the older sample size was too small.

Another extensively reported factor was gender, although its relationship is not clear. More clarity could be expected from attitudinal differences depending on the gender of the adult with ID. Although studies reported heterogeneous results, with gender differences manifesting in different sexuality areas, differences tend to appear. These differences could depend on gender stereotypes and beliefs of the selected sample. Differences could also relate to general knowledge about disability. Gender stereotypes have been found to influence social judgments in a higher way for women with intellectual disabilities [55]. Therefore, some relationship could be expected for attitudes towards sexuality. When examining data from samples of adults with ID, women seemed to be the ones with the most disadvantages. According to the included studies, they perceive more barriers to their sexuality and reported more negative experiences.

Differences across regions and cultural orientation support the hypothesis that culture is a strong related factor. Culture has already been related to attitudes towards different sexuality areas for the general population [56] and general attitudes towards intellectual disability [57]. In general, positive or negative attitudes towards sexuality seemed to relate to religiosity [56, 58] and the country’s economic context [58]. Indeed, acculturation and religiosity seem to interact at this point [56]. Some cultures still treat sexuality as a taboo subject. Therefore, it could be expected that this taboo be an added barrier that remains double for adults with ID [3]. This taboo could also explain differences across included studies. For the included studies, some variation across geographical regions is observed, with a negative tendency reported by studies in Indonesia, Israel, and Taiwan. One study in the UK did also report a negative tendency, yet the methodology of the study could explain this finding (small qualitative study, where the negative qualification is inferred from participants’ answers). Across the included studies, factors that affect differences across regions would be: country collectivism or individualism, how they treat sexuality, religious predominance, and power or degree of development of the country. These factors would influence not only people’s behavioral tendency, but also general policies of the country towards the issue.

Other related factors that require further investigation are social class, educational level, religiosity, and authoritarianism. Furthermore, extensive belief systems about sexuality in adults with ID have been reported to influence people’s judgment regarding the sexuality of adults with ID. These could be the real factors determining our final behavior (adding knowledge and policies), more than only our general attitudes. Concerns about harm and abuse have been reported in the present review as in previous studies [15]. However, little seems to be known in terms of how to give adults with ID strategies to cope with different scenarios while living a healthy intimate life. To summarize, the general public has limited understanding of the concept of intellectual disability [57], which could negatively affect the perception of the capacity of these people to learn and manage their intimacy.

This systematic review has some limitations that must be exposed. First, the attitudinal scope could be broader than the one selected. Some excluded studies reported other valuable information, such as perceptions towards giving active support to the sexuality of people with ID or experiences towards their intimate life. So did those studies that only focused on romantic relationships but not their sex life. Second, as only English peer-reviewed journal articles were included, other valuable findings reported by conference papers or grey literature were not considered by the present paper.

However, the present study makes important contributions, as it gives a systematic and in-depth look into the current empirical knowledge on attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with ID, starting by the personal perspective of adults with ID. Further studies should work on shedding light on those relationships that remain unclear, and explore other new factors that could affect attitudes. As culture seems to be a strong related factor, further investigation is required. Research in personality traits could be interesting, as they have been suggested to affect attitudes. Indeed, the authoritarian personality relates to more negative attitudes [40]. However, no more studies into personality traits have been found. Attitudes and beliefs described by the protagonist of the issue, adults with ID, should be more extensively explored.

Conclusions

Current attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with ID seems to be more positive than in past decades [13]. However, working on attitudinal changes in society is still needed, due to its relevance for the sexual and even overall well-being of adults with ID. In the present review, different factors have showed to be related to more positive or negative attitudes, especially in terms of involvement with intellectual disabilities (i.e., family member, staff, general population) and sociodemographic factors such as age, culture, and education.

All the above should be taken into consideration for the population, parental and staff training, educational programs, and general policies in sexuality and ID. The main aim should be to provide adults with ID with a good support for a healthy relational and sex life. In order to achieve it, we should target what directly affects the unrealistic population attitudes, or what makes those attitudes not materialize into supportive behaviors. As stated at the beginning of the present paper, sexuality and its expression are a main human right, one that directly influences self-perceived quality of life in adults. Therefore, it is our responsibility as researchers and professionals in the intellectual disability field to make a difference, in order to promote an integral and good quality of life for adults with ID.

References

Cuskelly, M., Gilmore, L.: Attitudes to sexuality questionnaire (individuals with an intellectual disability): scale development and community norms. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 32, 214–221 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250701549450

Esmail, S., Darry, K., Walter, A., Knupp, H.: Attitudes and perceptions towards disability and sexuality. Disabil. Rehabil. 32, 1148–1155 (2010). https://doi.org/10.3109/09638280903419277

Winges-Yanez, N.: Why all the talk about sex? An authoethnography identifying the troubling discourse of sexuality and intellectual disability. Sex Disabil. 32, 107–116 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-013-9331-7

Charitou, M., Quayle, E., Sutherland, A.: Supporting adults with intellectual disabilities with relationships and sex: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research with staff. Sex Disabil. 39, 113–146 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09646-z

Chrastina, J., Večeřová, H.: Supporting sexuality in adults with intellectual disability—a short review. Sex Disabil. 38, 285–298 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-9546-8

Buntinx, W.H.E., Schalock, R.L.: Models of disability, quality of life, and individualized supports: Implications for professional practice in intellectual disability. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 7, 283–294 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2010.00278.x

Sinclair, J., Unruh, D., Lindstrom, L., Scanlon, D.: Barriers to sexuality for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a literature review. Educ. Train Autism Dev. Disabil. 50, 3–16 (2015)

Dukes, E., McGuire, B.E.: Enhancing capacity to make sexuality-related decisions in people with an intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53, 727–734 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01186.x

Baines, S., Emerson, E., Robertson, J., Hatton, C.: Sexual activity and sexual health among young adults with and without mild/ moderate intellectual disability. BMC Public Health 18, 667 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5572-9

Gil-Llario, M.D., Morell-Mengual, V., Ballester-Arnal, R., Díaz-Rodríguez, I.: The experience of sexuality in adults with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 62, 72–80 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12455

Jahoda, A., Pownall, J.: Sexual understanding, sources of information and social networks; the reports of young people with intellectual disabilities and their non-disabled peers. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 58, 430–441 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12040

Hingsburger, D., Tough, S.: Healthy sexuality: attitudes, systems, and policies. Res. Pract. Persons Severe Disabl. 27, 8–17 (2002). https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.27.1.8

Aunos, M., Feldman, M.A.: Attitudes towards sexuality, sterilization and parenting rights of persons with intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 15, 285–296 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2002.00135.x

Futcher, S.: Attitudes to sexuality of patients with learning disabilities: a review. Br. J. Nurs. 20, 8–14 (2011). https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2011.20.1.8

Brown, M., McCann, E.: The views and experiences of families and direct care support workers regarding the expression of sexuality by adults with intellectual disabilities: a narrative review of the international research evidence. Res. Dev. Disabil. 90, 80–91 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.04.012

Lam, A., Yau, M., Franklin, R., Leggat, C., Peter, A.: Public opinion on the sexuality of people with intellectual disabilities: a review of the literature. Sex Disabil. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09674-9

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L.A.: PRISMA-P Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4, 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G.: The PRISMA group: preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 6, e1000097 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Ryan, R., Synnot, A., Prictor, M., Hill, S.: Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group Data extraction template for included studies. CCCG. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources (2016). Accessed 11 Nov 2020.

Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M., Vedel, I.: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (2018). Accessed 1 Dec 2020.

Christian, L.A., Stinson, J., Dorson, L.A.: Staff values regarding the sexual expression of women with developmental disabilities. Sex Disabil. 19, 283–291 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017957409670

Chou, Y.C., Lu, Z.Y.J., Pu, C.Y.: Attitudes toward male and female sexuality among men and women with intellectual disabilities. Women Health 55, 663–678 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2015.1039183

Siebelink, E.M., de Jong, M.D.T., Taal, E., Roelvink, L., Taylor, S.J.: Sexuality and people with intellectual disabilities: assessment of knowledge, attitudes, experiences, and needs. Ment. Retard. 44, 283–294 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2006)44[283:SAPWID]2.0.CO;2

Karellou, J.: Parents’ attitudes towards the sexuality of people with learning disabilities in Greece. J. Dev. Disabil. 13, 73–88 (2007)

Bazzo, G., Nota, L., Soresi, S., Ferrari, L., Minnes, P.: Attitudes of social service providers towards the sexuality of individuals with intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 20, 110–115 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00308.x

Grieve, A., McLaren, S., Lindsay, W., Culling, E.: Staff attitudes towards the sexuality of people with learning disabilities: a comparison of different professional groups and residential facilities. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 37, 76–84 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2008.00528.x

Meaney-Tavares, R., Gavidia-Payne, S.: Staff characteristics and attitudes towards the sexuality of people with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 37, 269–273 (2012). https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2012.701005

Parchomiuk, M.: Specialists and sexuality of individuals with disability. Sex Disabil. 30, 407–419 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-011-9249-x

Pebdani, R.N.: Attitudes of group home employees towards the sexuality of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Sex Disabil. 34, 329–339 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-016-9447-7

Ryan, D., McConkey, R.: Staff attitudes to sexuality and people with intellectual disabilities. Ir. J. Psychol. 21, 88–97 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1080/03033910.2000.10558242

Swango-Wilson, A.: Caregiver perception of sexual behaviors of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Sex Disabil. 26, 75–81 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-008-9071-2

Yool, L., Langdon, P.E., Garner, K.: The attitudes of medium-secure unit staff toward the sexuality of adults with learning disabilities. Sex Disabil. 21, 137–150 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025499417787

Young, R., Gore, N., McCarthy, M.: Staff attitudes towards sexuality in relation to gender of people with intellectual disability: a qualitative study. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 37, 343–347 (2012). https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2012.704983

Saxe, A., Flanagan, T.: Factors that impact support workers’ perceptions of the sexuality of adults with developmental disabilities: a quantitative analysis. Sex Disabil. 32, 45–63 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-013-9314-8

Ditchman, N., Easton, A.B., Batchos, E., Rafajko, S., Shah, N.: The impact of culture on attitudes toward the sexuality of people with intellectual disabilities. Sex Disabil. 35, 245–260 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9484-x

Esterle, M., Munoz Sastre, M.T., Mullet, E.: Judging the acceptability of sexual intercourse among people with learning disabilities: French laypeople’s viewpoint. Sex Disabil. 26, 219–227 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-008-9093-9

Franco, D.G., Cardoso, J., Neto, I.: Attitudes towards affectivity and sexuality of people with intellectual disability. Sex Disabil. 30, 261–287 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-012-9260-x

Jones, L.K., Binger, T.E., McKenzie, C.R., Ramcharan, P., Nankervis, K.: Sexuality, pregnancy and midwifery care for women with intellectual disabilities: a pilot study on attitudes of university students. Contemp. Nurse 35, 47–57 (2010). https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2010.35.1.047

Karellou, J.: Laypeople’s attitudes towards the sexuality of people with learning disabilities in Greece. Sex Disabil. 21, 65–84 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023562909800

Katz, S., Shemesh, T., Bizman, A.: Attitudes of university students towards the sexuality of persons with mental retardation and persons with paraplegia. Br. J. Dev. Disabil. 46, 109–117 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1179/096979500799155720

McConkey, R., Leavey, G.: Irish attitudes to sexual relationships and people with intellectual disability. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 41, 181–188 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12036

Morales, G.E., Lopez, E.O., Esterle, M., Muñoz, M.T., Mullet, E.: Judging the acceptability of sexual intercourse among people with learning disabilities: a Mexico-France comparison. Sex Disabil. 28, 81–91 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-010-9147-7

Parchomiuk, M.: Model of intellectual disability and the relationship of attitudes towards the sexuality of persons with an intellectual disability. Sex Disabil. 31, 125–139 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-012-9285-1

Sankhla, D., Theodore, K.: British attitudes towards sexuality in men and women with intellectual disabilities: a comparison between White Westerners and South Asians. Sex Disabil. 33, 429–445 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-015-9423-7

Morales, G.E., Lopez, E.O., Mullet, E.: Acceptability of sexual relationships among people with learning disabilities: family and professional caregivers’ views in Mexico. Sex Disabil. 29, 165–174 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-011-9201-0

Cuskelly, M., Bryde, R.: Attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with an intellectual disability: parents, support staff, and a community sample. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 29, 255–264 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250412331285136

Tamas, D., Brkic Jovanovic, N., Rajic, M., Bugarski Ignjatovic, V., Peric Prkosovacki, B.: Professionals, parents and the general public: attitudes towards the sexuality of persons with intellectual disability. Sex Disabil. 37, 245–258 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-09555-2

Chou, Y.C., Lu, Z.Y.J., Lin, C.J.: Comparison of attitudes to the sexual health of men and women with intellectual disability among parents, professionals, and university students. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 43, 164–173 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1259465

Evans, D.S., McGuire, B.E., Healy, E., Carley, S.N.: Sexuality and personal relationships for people with an intellectual disability. Part II: Staff and family carer perspectives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53, 913–921 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01202.x

Gilmore, L., Chambers, B.: Intellectual disability and sexuality: attitudes of disability support staff and leisure industry employees. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 35, 22–28 (2010). https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250903496344

Oliver, M.N., Anthony, A., Leimkuhl, T.T., Skillman, G.D.: Attitudes toward acceptable socio-sexual behaviors for persons with mental retardation: implications for normalization and community integration. Educ. Train. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. 37, 193–201 (2002)

Brown, R.D., Pirtle, T.: Beliefs of professional and family caregivers about the sexuality of individuals with intellectual disabilities: examining beliefs using a Q-methodology approach. Sex Educ. 8, 59–75 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810701811829

Winarni, T.I., Hardian, H., Suharta, S., Ediati, A.: Attitudes towards sexuality in males and females with intellectual disabilities: Indonesia Setting. Intellect. Disabl. Diagn. J. 6, 43–48 (2018). https://doi.org/10.6000/2292-2598.2018.06.02.3

Twenge, J.M., Sherman, R.A., Wells, B.E.: Changes in American adults’ sexual behavior and attitudes, 1972–2012. Arch. Sex. Behav. 44, 2273–2285 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0540-2

Coleman, J.M., Brunell, A.B., Haugen, I.M.: Multiple forms of prejudice: How gender and disability stereotypes influence judgments of disabled women and men. Curr. Psychol. 34, 177–189 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9250-5

Ahrold, T.K., Meston, C.M.: Ethnic differences in sexual attitudes of U.S. college students: gender, acculturation, and religiosity factor. Arch. Sex. Behav. 39, 190–202 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9406-1

Scior, K.: Public awareness, attitudes and beliefs regarding intellectual disability: a systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 32, 2164–2182 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.005

Jung, J.H.: A cross-national analysis of religion and attitudes toward premarital sex: do economic contexts matter? Sociol. Perspect. 59, 798–817 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121415595428

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, Government of Spain, under grant PGC2018-097086-A-I00; Government of Aragon (Group S31_20D). Department of Innovation, Research and University and FEDER 2014–2020, "Building Europe from Aragón".

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author Ana Belén Correa declares she has no conflict of interest. Author Ángel Castro declares he has no conflict of interest. Author Juan Ramón Barrada declares he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Correa, A.B., Castro, Á. & Barrada, J.R. Attitudes Towards the Sexuality of Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Sex Disabil 40, 261–297 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-021-09719-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-021-09719-7