Abstract

This study investigates the factors influencing surname initial techniques in academic publications and their impact on citation counts. Focusing on the disciplines of Economics, Psychology, Political Science, and Sociology, we utilized data from the top 500 universities listed in the Shanghai List. Examining 70.377 academic publications from 2.278 academics published between 2011 and 2020, the study reveals that alphabetical ordering is more prevalent in Economics and Political Science. Academics with surnames placed at the beginning of the alphabet in these fields experience increased visibility and recognition. Conversely, those with surnames placed at the end of the alphabet face disadvantages and often employ strategies such as changing surname initials, using hyphenated surnames, or adding prefixes to improve their positioning in the author list of the article. These strategies, influenced by factors like the number of authors, country of origin, gender and whether the advantage is gained or not in positioning of author list, help mitigate the unfairness caused by alphabetization and positively contribute to authors’ citation statistics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multi-author studies have increasingly become a norm within the academic community, as evidenced by some important research (Abt, 1992; Hudson, 1996; Waltman, 2012). This trend highlights a significant challenge: how to list authors in scholarly publications. When addressing this problem, journals typically employ two primary methods: contribution-based sorting and alphabetical sorting. The former lists authors in descending order of their contribution to the paper, while the latter arranges authors by the alphabetical order of their surname initials. Studies indicate that alphabetical sorting may be unfair, especially to those whose surnames appear at the end of the alphabet (Arsenault & Lariviere, 2015; Efthyvoulou, 2008; Einav & Yariv, 2006; Laband & Tollison, 2006; Rudd, 1977; Shevlin & Davies, 1997; Van Praag & Van Praag, 2008). Such authors are less likely to be listed as the first author in multi-author papers in which alphabetical order is followed (Levitt & Thelwall, 2013; Rudd, 1977) and tend to be positioned at the end of the reference list, which are also alphabetically ordered (Huang, 2015; Shevlin & Davies, 1997).

Being at the beginning of the author list in multi-author publications is crucial, as it significantly boosts academic visibility and recognition (Arsenault & Lariviere, 2015; Efthyvoulou, 2008; Laband & Tollison, 2006; Rudd, 1977; Shevlin & Davies, 1997; Van Praag & Van Praag, 2008; Weber, 2018; Yuret, 2019). Due to time constraints, readers may not thoroughly explore all authors of a paper, instead focusing on the works of those listed first (Efthyvoulou, 2008). Additionally, even if the authors are listed alphabetically, readers might assume that the listing is based on contribution, leading them to perceive the first-listed author as the most significant contributor (Maciejovsky et al., 2009; Shevlin & Davies, 1997). Those who benefit most from such effects are authors who possess an alphabetic advantage. Conversely, academics with surnames starting with letters placed at the end of the alphabet may face disadvantages, potentially opting out of collaborations with alphabetically advantaged colleagues or choosing to publish in journals that do not follow alphabetical order (Einav & Yariv, 2006; Kadel & Walter, 2015; Laband, 2002; Van Praag & Van Praag, 2004). Some may even resort to changing their surname initials to improve their positioning in author lists (Efthyvoulou, 2008).

This study aims to explore strategies for changing surname initials among academics in Economics, Psychology, Political Science, and Sociology departments of the top 500 universities in the Shanghai List. It seeks to understand the factors influencing these strategies and assess how such changes might impact academic evaluation metrics, such as citation rates.

This paper will discuss the literature on alphabetization in chapter 2, describe the main data in chapter 3, and analyze surname initial techniques in chapter 4 and 5. Chapter 6 will provide a comprehensive evaluation of the study’s findings.

Literature review

The increase in multi-authored works in academic publishing has emerged as a significant trend within the research community. Studies by Abt (1992), Hudson (1996), and Waltman (2012) have not only confirmed the persistence of this trend but have also shown that it has accelerated due to the expanding scope and increasing technical complexities in fields such as economics. Research conducted by Nudelman and Landers (1972) and Diamond (1985) suggests that academic collaborations afford authors greater recognition and broader citation reach compared to single-author studies, thereby amplifying their scientific impact. However, the increase in multi-authored works also brings with it the question of how authors should be listed. Specifically regarding this issue, two main methods of sorting are prominent: alphabetical sorting and contribution-based sorting.

The method of alphabetization, used to list authors in multi-author studies, has been adopted extensively across various academic departments due to its simplicity (Birnholtz, 2007; Hilmer & Hilmer, 2005; Maciejovsky et al., 2009; Waltman, 2012; Yuret, 2016). Particularly prevalent in disciplines such as mathematics, economics, and high energy physics (Birnholtz, 2007; Fernandes & Cortez, 2020; Waltman, 2012). However, it is less preferred in fields like psychology and sociology, highlighting differing perspectives of sorting across disciplines (Einav & Yariv, 2006; Yuret, 2016).

Alphabetization can lead to various forms of unfairness among authors. For instance, citation formats like ‘Prof. A et al.’ tend to disproportionately highlight the first-listed author, leading to a concentration of citations on this individual (Einav & Yariv, 2006; Van Praag & Van Praag, 2004). Research by Efthyvoulou (2008) and Van Praag and Van Praag (2008) demonstrates that an author’s surname placement within the alphabet can significantly affect access to their work and, consequently, their scientific impact. Further studies, such as those by Laband and Tollison (2006) and Arsenault and Lariviere (2015), indicate that alphabetical bias in academic publishing can negatively influence recognition and citation rates, particularly disadvantaging authors whose surnames appear at the end of the alphabet.

The impact of alphabetical sorting extends beyond citation metrics, potentially affecting academic careers. Studies have shown that scholars with surnames early in the alphabet are more likely to occupy prestigious positions and attain higher academic ranks (Efthyvoulou, 2008; Einav & Yariv, 2006; Yuret, 2019), underlined the profound implications of alphabetization on academic inequality.

Academics disadvantaged by alphabetical order have responded in various ways to this unfairness. Einav and Yariv (2006) observed that such individuals are less likely to collaborate in prestigious journals. Efthyvoulou (2008) noted that some authors have attempted to manipulate the alphabetical order of surnames through strategic changes. Additionally, Laband (2002) and Kadel and Walter (2015) suggest that authors might adjust not only their publishing strategies but also their collaborative endeavors to mitigate this disadvantage.

A summary table of the literature (Table 1) follows this discussion. While the literature predominantly highlights the advantages of alphabetic positioning in academia, further research is necessary to explore strategies for counteracting these disadvantages and to examine the factors influencing their adoption. Moreover, the extent to which these strategies aid in enhancing an author’s recognition and citation rates needs to be assessed. Beyond existing strategies for surname modification, it is also crucial to investigate new approaches and evaluate their effectiveness under various conditions.

Main data

We introduce the dataset created using the Scopus academic database for analyzing surname initial techniques. Initially, we collected the contact information of Associate Professors and Full Professors from the Sociology, Economics, Psychology, and Political Science departments of the top 500 universities listed in the Shanghai List. This information was gathered from the web pages of the respective universities (Yuret et al., 2023). Academics were asked, without any specific criteria, to identify and share their three best publications from 2011 to 2020 in descending order, that they believed contributed most significantly to science. Then, we gathered information on the top three publication preferences from 2.278Footnote 1 individuals out of over 32.000 academics. Our dataset was then compiled by extracting bibliometric data from the Scopus academic database.

The analysis focuses on these four disciplines due to their varying degrees of alphabetization, distinctive structural characteristics, and the availability of top three publication preferences from these departments (Birnholtz, 2007; Fernandes & Cortez, 2020; Waltman, 2012). Additionally, these academic disciplines are chosen because they heavily rely on publications in academic journals and have higher rates of multi-authorship compared to other fields (Henriksen, 2018; Oromaner, 1975; White et al., 1982).

Biographical data of authors

Participants, whose top three publication preferences were recorded and summarized in Table 2, hailed from a total of 42 different countries (Yuret et al., 2023). The majority of participants are of European origin, with a response rate of 8.9% to our emails from this continent. South America had the highest response rate, at 14.1%.

A total of 2.278 individuals participated in our study, including 750 academics from the Psychology department, 737 from the Economics department, 425 from the Political Science department, and 366 from the Sociology department. Out of these, 611 are female academics, comprising 27% of the total sample. The Psychology department had the highest proportion of female academics, at 36%.

Authors’ bibliometric data

A total of 70.377 articles authored by the 2.278 academics in our sample were analyzed, including single-authored articles. The rates of alphabetization based on the number of authors are detailed in Table 3. The departments of Economics and Political Science are notable for their intensive adherence to alphabetical order. To assess this more accurately, it is crucial to determine whether the alphabetization results from the randomness phenomenon, as described by Shevlin and Davies (1997). Randomness rates were calculated using the formula 1/n! based on the number of authors in an article represented by ‘n’, and these rates are presented in the last row of Table 3 (Yuret, 2016). The alphabetization rates in the Economics and Political Science departments significantly exceeded the randomness rates, indicating a deliberate use of alphabetical ordering in these fields. Another observation from the randomness rates is that alphabetization rates decrease as the number of authors increases, since a greater number of authors reduces the likelihood of alphabetical listing (Waltman, 2012).

Participation of authors in studies with multiple authors/single author according to alphabetical groups

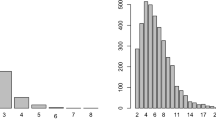

The first strategy that authors with an alphabetical disadvantage might employ to avoid this bias is to refrain from engaging in co-authored works (Laband, 2002; Van Praag & Van Praag, 2004). To determine if the authors in our dataset exhibit such a tendency, we divided the authors from four different departments into five groups based on the alphabetical order of their surname initials. Our primary goal is to assess the extent to which author groups participate in co-authored studies mostly. Figure 1 illustrates the ratio of co-authored works to all published articles by authors from these four departments, categorized according to their alphabetical groups. The figure reveals that in the Economics and Political Science departments, where alphabetization is practiced intensively, there is no observable decrease in the rate of participation in co-authored studies as we move to alphabetically disadvantaged groups.

In addition to analyzing the proportion of multi-authored articles among authors with different surname initials, we also examined the distribution of single-authored articles to investigate whether authors with an alphabetical disadvantage are more likely to refrain from co-authoring and publish independently.

Figure 2 represents the proportion of single-authored articles to all published articles within each group, in order to determine if there is an overweight of authors with alphabetically disadvantaged surnames in single-authored publications. The analysis reveals that in the Political Science and Sociology departments, there is a slight increase in the proportion of single-authored articles in the K–O group, which indicates that authors with surnames in this group might prefer to publish independently. However, the U–Z group does not show a significant deviation, suggesting that the alphabetical disadvantage does not lead to a higher rate of single-authored publications in these departments.

Therefore, we cannot conclude that authors whose surnames start with letters placed at the end of the alphabet are less likely to engage in co-authored studies or more likely to engage in single-authored studies.

Publication rates of authors following the alphabetical ordering according to alphabetical groups

Another strategy that disadvantaged authors might employ is to publish in journals that do not follow alphabetical ordering (Einav & Yariv, 2006). To partially detect this behavior, as in the previous section, the authors were divided into five groups based on the initials of their surnames, and the rate of alphabetized articles they published was calculated. As shown in Fig. 3, it was revealed that articles published by authors in the Departments of Economics and Political Sciences, whose surnames begin with A–E, are alphabetized at a higher rate compared to those whose surnames begin with U–Z. However, this effect is not strong and only indicates a moderate influence. In the Psychology and Sociology departments, where alphabetical ordering is less common, the alphabetization rates for articles by academics are significantly low. Consequently, we could not find strong evidence suggesting that academics with early initials in their surnames preferentially publish in journals where alphabetical order is intensely followed.

First alphabetic surname, two last names and hyphenated surname techniques

In this article, the naming of the First Alphabetic Surname technique is used instead of the Two Last Names technique mentioned in the literature. The reason for this is that we will introduce an additional technique in this chapter.

Authors with surnames that appear at the end of the alphabet have mainly adopted three different strategies to mitigate this disadvantage. The first two of these strategies were discussed in “Participation of Authors in Studies with Multiple Authors/Single Author According to Alphabetical Groups” and “Publication Rates of Authors Following the Alphabetical Ordering According to Alphabetical Groups” Sections, respectively, and it was found that there was no strong inclination that authors favored these strategies. Chapters 4 and 5 will introduce our third strategy, which involves techniques for changing the initial of the surname. These chapters will explore the factors influencing the preference for these techniques and analyze their impact on academic evaluation methods, such as citation counts.

The first main technique, the First Alphabetic Surname technique, involves the author using the earliest initial of two different surnames (Efthyvoulou, 2008). The Two Last Names technique (supporting technique) occurs when the author opts to use two different last names, meaning that they might appear as Professor A in one article and Professor B in another. Finally, in the Hyphenated Surname technique, authors combine their surnames using a hyphen (-), thus keeping their surnames together (Jones, 2024).

Our sample consisted of academics with two or more surnames from four different departments in our dataset (Yuret et al., 2023). A total of 613Footnote 3 individuals with hyphenated and multiple two or more surnames were included in our analysis.

In Table 4, a total of 17.219 academic publications authored by 613 academics between 2011 and 2020 were analyzed. The majority of these publications, constituting 58% of the total, were from the Psychology department. The Economics and Political Science departments, known for intense alphabetization practices, recorded the lowest average number of authors per article. The hyphenated surname technique is utilized at a nearly consistent rate across all departments, though it is slightly more common in Sociology than in the others. The tendency to select a surname that provides an alphabetical advantage among those with two or more surnames was comparable across all departments. However, the number of articles that benefited from earlier surname selection, whether through hyphenated or first alphabetic surname techniques, was higher in the Economics and Political Science departments.

Women may use two different surnames after marriage and may choose to drop their premarital surname if the alphabetical order of their postmarital surname initials is more favorable than that of their maiden surnames. To analyze this situation, gender ratios across departments were collected. As shown in Table 5, the departments with the highest female rates are in Psychology (39%) and Sociology (45%). Another important point from the table is that the relatively high rates of authors in the Economics department who use two or more different surnames. Several reasons can explain this phenomenon: Firstly, the prevalent use of alphabetical ordering in this department encourages authors to strategically improve their alphabetical positioning (see Table 4, column 7). Secondly, a high proportion of authors from countries with a tradition of multiple surnames, such as Spain, Portugal, and Brazil- referred to as ‘Countries with many surnames’ facilitates the use of varied surnames (see Table 5, column 7). Thirdly, the relatively large distance between surname initials in Economics (8,77) motivate authors to alternate between surnames to gain an alphabetical advantage (see Table 5, column 6).

Table 6 categorizes authors into three different groups based on the alphabetical distance between their surname initials: 1–8 letters, 9–16 letters, and 17–25 letters. This classification aims to explore whether authors increasingly adopt strategic behaviors as the distance between their surname initials widens. Although there is no clear trend for the hyphenated surname strategy, the third column of Table 6 shows an increase in the use of the ‘First Alphabetic Surname’ technique as we move to more alphabetical distance. This trend is evident in both the analysis of authors and articles, particularly noticeable in the 17–25 letter range, where the strategy is employed 7 percentage points more frequently by authors and 12 percentage points more frequently in articles compared to the 1–8 letter range. A moderate increase is observed in the ‘Two Last Names’ technique (see column 4). The last column of the table highlights that at higher alphabetical distances, authors are more likely to gain a positional advantage in the author list by employing the ‘First Alphabetic Surname’ technique.

Regression results

Regression estimates were conducted using a department-fixed logit model, where the surname techniques mentioned in the previous section were included as dependent variables.

Variables are;

-

‘Distance’ is the alphabetical distance between the initials of two surnames.

-

‘Number of Authors’ refers to the total number of authors of an article.

-

‘Rank of Authors’ specifies the position of the target author in the author list.

-

‘Top 3’ denotes whether the article ranks among the author’s three highest priority publications. It is marked as 1 if so.

-

‘Gender’ represents the gender of the authors, marked as 1 if female.

-

‘Countries (Many Surnames)’ indicates citizenship in Spain, Portugal, or Brazil. It is marked as 1 for authors from these countries.

-

‘First Alphabetic Surname Advantage’ and ‘Hyphenated Surname Advantage’ determines whether the advantage is obtained in author list by using the surname that comes earlier in the alphabet. It is marked as 1 if this advantage is realized.

-

‘Year Adjusted Citation’ displays citation metrics adjusted by publication year.

Table 7 lists the results of the logit regression model, which analyzed the factors affecting the use of mentioned strategies only in the alphabetically sorted subsample of articles. As mentioned before, whether authors gain an advantage by using these techniques depends on the list of authors following alphabetical rules, and in order to fully isolate this effect, regression was performed on this subsample.

To summarize the results of the regression:

-

The ‘Distance’ variable in the regression analysis was statistically significant in predicting the use of the First Alphabetic Surname technique. An increase in the alphabetical distance between surnames in alphabetized articles correlated with a decrease in the use of surnames that offer an alphabetical advantage, indicating a negative impact of the distance parameter on this tehcnique.

-

The ‘Number of Authors’ variable significantly influenced the adoption of first two techniques. In alphabetized articles, a positive relationship was observed, suggesting that as the number of authors increased, there was a corresponding rise in the adoption of strategic behaviors. This supports the idea that with more authors, individuals are more likely to use surname initial techniques to enhance their position in the author list.

-

The ‘Rank of Authors’ variable was significant in all regressions, indicating that authors strategically change their surnames to secure a favorable position in the author list. Authors at the beginning of the list tended to maneuver their surnames strategically, while those at the end did not exhibit such strategic behaviors.

-

The ‘Gender’ variable was significant in the first and third regressions, showing that women were more likely to use the first alphabetic surname/hyphenated surname, often opting for a surname acquired after marriage, especially if it provided an alphabetical advantage.

-

The ‘Countries (Many Surnames)’ variable showed statistical significance in the second regression, indicating that being a citizen of certain countries increased the likelihood of using different surnames, highlighting the influence of possessing multiple surnames on this choice.

-

The ‘First Alphabetic Surname Advantage’ variable had a positive and significant effect on the preference for the earlier surname in the alphabet, reinforcing that authors strategically choose the first alphabetic surname when it offers an advantage in the author list rankings.

-

The ‘Year Adjusted Citation’ variable demonstrated a positive relationship with the First Alphabetic Surname technique. This suggests that using the earlier surname in the alphabet is associated with higher citation statistics, indicating that authors who employ this technique do not suffer from reputational losses but, instead, gain greater visibility and recognition in academia.

Prefix and both prefix/surname techniques

The second main technique, the ‘Prefix’ tehcnique, involves authors gaining an alphabetical advantage by adding prefixes such as De, Da, Di, Von, Van before their surnames (Efthyvoulou, 2008). Consider two academics: Professor De Z. and Professor Van A. The first academic can improve his/her alphabetical position by using the prefix ‘De’. However, for the second author, using the prefix ‘Van’ may worsen his alphabetical position. In essence, if the initial of the prefix comes earlier in the alphabet than the surname initial, authors may use the prefix. The ‘Both Prefix and Surname’ technique, an supporting technique, occurs when an author chooses to use both the prefix and the surname. Thus, an article might be placed as Prof. De A in one instance and Prof. A in another.

A subsample was created from academics in four different departments from our dataset (Yuret et al., 2023). This subsample included only those with prefixes, specifically identifying two different prefixes starting with the letters ‘D’ and ‘V’. A total of 2.953 publications authored by 55 academicians were analyzed.

Data regarding the authors are given in the Table 8 below.

In Table 8, faculty members whose prefixes start with the letter ‘D’ are predominant in all departments, with the exception of the Sociology department, where their use is less common. Across all departments, the adoption of prefixes is widespread. Additionally, the department of Economics shows a tendency for the ‘Both Prefix and Surname’ technique, which incorporates both prefixes and surnames. In the last column of the table, the numbers of academics from the Netherlands and Belgium are listed. These countries are described as ‘countries with common prefix’ and academics from these regions tend to favor using their prefixes more frequently than their surnames.

Table 9 reveals that in all departments, articles where prefixes are preferred over surnames are predominant. However, the advantage of securing a better position in the author list by using the prefix strategy is more apparent in the Economics and Political Science departments. This is due to the higher rate of alphabetization in these departments. As previously mentioned, the presence of alphabetization is a prerequisite for gaining an advantage through surname techniques.

Table 10 shows that in the Economics department, the ‘D’ prefix is preferred more frequently compared to the others. The primary reason for this is the higher number of articles that authors gain an advantage through the use of prefixes in the author list. Additionally, the higher proportion of academics from Belgium and the Netherlands, countries that prioritize the use of prefixes regardless of alphabetical order, contributes to the increased use of prefixes in the Economics Department.

The ‘Distance’ variable in the table represents the alphabetical distance between the initial letter of the prefix and the initial letter of the author’s surname. A positive value indicates that the prefix comes alphabetically before the surname, motivating authors to use prefixes more frequently. Conversely, a negative value indicates the opposite. Therefore, the reason why the ‘V’ prefix is less preferred in the Economics becomes clear, due to its relatively disadvantageous position in the alphabetical order.

Regression results

Regression estimates were conducted using a department-fixed logit model, where the techniques ‘Prefix’ and ‘Both Prefix and Surname’ discussed in this chapter were included as dependent variables.

Unlike the previous section, our new variables are:

-

‘Letter’ assigns the value 1 for the prefix ‘D’ and 0 for the prefix ‘V’.

-

‘Distance’ measures the alphabetical distance between the initials of the prefix and the surname.

-

‘Prefix Advantage’ assigned the value of 1 if using prefix results in an advantage, and 0 if it does not.

-

‘Prefix Front’ sets the value 1 if the initial of the author’s prefix precedes the initial of his/her surname in the alphabet, and 0 otherwise.

-

‘Country Prefix’ assigns a value of 1 to citizens from either the Netherlands or Belgium.

Table 11 presents the results of a logit regression model that examines the factors influencing the use of mentioned techniques exclusively in articles that follows alphabetization.

To summarize our findings:

-

The ‘Distance’ variable showed a significant effect in the regression model that analyzed the use of prefixes as dependent variables. The results indicate that authors are less likely to use prefixes as the alphabetical distance between the prefix and surname initials increases.

-

The ‘Number of Authors’ variable was significantly influential in the second regression. As the number of authors in articles increased, so did the likelihood of authors using both prefixes and surnames. This suggests that authors use this strategy to boost their visibility and position in the author list, especially as competition for top ranking intensifies.

-

The ‘Prefix Advantage’ variable was significant in both regressions, although with varying signs. In the first regression, authors preferred using prefixes to secure a better position in the author ranking. In the second regression, the potential advantage from using prefixes reduced the tendency to use multiple surname options, indicating that authors who focus only on prefixes generally avoid using both of them.

-

The ‘Countries Common Prefix’ variable was significant in the regression that focused on prefix usage. Authors from the Netherlands and Belgium, where there is a high preference for prefixes, were more likely to choose prefixes as surnames, despite starting with the less advantageous letter ‘V.’

-

The ‘Year Adjusted Citation’ variable had a significant impact in the second regression, showing a negative effect on the strategy of considering multiple surname options. This finding suggests that articles with a single surname in the author list tend to receive more citations, highlighting a possible connection between an author’s reputation and their citation counts.

Conclusion and discussion

This study investigates the factors influencing surname initial techniques in academic publications, focusing on the disciplines of Economics, Psychology, Political Science, and Sociology. First, it was determined to what extent authors in these four academic disciplines are listed alphabetically in their publications. Notably, the Economics and Political Science departments exhibit higher rates of alphabetical ordering compared to random probabilities, indicating a deliberate use of alphabetical listing. Because these departments heavily utilize alphabetical ordering, authors in these two departments with surnames early in the alphabet secure better positions in the author lists of co-authored works. This leads to greater academic recognition and visibility for them.

Authors with surnames later in the alphabet may attempt to escape the disadvantages of alphabetical ordering by avoiding co-authored works and publishing in non-alphabetized journals. However, the findings show no significant decrease in co-authorship or increase in single-authorship among these alphabetically disadvantaged authors, indicating that they do not avoid collaboration despite potential drawbacks. Additionally, there is only a moderate preference for non-alphabetized ordering among these authors, suggesting limited use of this strategy.

In addition to avoiding co-authored works and publishing in non-alphabetized journals, authors can also enhance their alphabetical position by altering their surname initials. This study examined five different surname initial techniques and analyzed the factors influencing their use as well as their impact on citation statistics. A series of regression analyses were conducted, and the results indicate a significant relationship between the various factors. Specifically, a higher number of authors in an article is associated with an increased likelihood of employing surname strategies, as authors seek improved rankings in the author list. Additionally, the use of the techniques was more prevalent when authors were certain of obtaining a better position in the author list. Gender, particularly among female academics, and country of origin significantly impact the adoption of these strategies, suggesting geographical and cultural influences. Notably, employing these strategies did not adversely affect academic reputation; instead, they often led to increased citations and better rankings.

This study sheds light on the intricate nature of surname initial techniques. These findings underscore that surname techniques are a multifaceted behavior influenced by various factors. Future research can build on this framework to gain a deeper understanding of these techniques and better evaluate their impact on academic publications. Ultimately, surname techniques are a significant issue in the academic world, with varying techniques employed across different departments and an increasing tendency towards these techniques due to multiple influencing factors.

Notes

Information about academics who did not answer our question in the correct format and whose Scopus profiles were not available were excluded from our dataset.

Three academicians from the Department of Economics and five academicians from the Department of Psychology were excluded from our sample because they did not have a Scopus profile.

References

Abt, H. (1992). Publication practices in various sciences. Scientometrics, 24(3), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02051040

Arsenault, C., & Larivière, V. (2015). Is Paper Uncitedness a Function of the Alphabet? In ISSI.

Birnholtz, J. P. (2007). When do researchers collaborate? Toward a model of collaboration propensity in science and engineering research. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(14), 2226–2237. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20684

Diamond, A. M. (1985). The money value of citations to single-authored and multiple-authored articles. Scientometrics, 8(5–6), 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02016992

Efthyvoulou, G. (2008). Alphabet economics: The link between names and reputation. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(3), 1266–1285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2007.12.005

Einav, L., & Yariv, L. (2006). What’s in a surname? The effects of surname initials on academic success. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526085

Fernandes, J. M., & Cortez, P. (2020). Alphabetic order of authors in scholarly publications: A bibliometric study for 27 scientific fields. Scientometrics, 125(3), 2773–2792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03686-0

Henriksen, D. (2018). What factors are associated with increasing co-authorship in the social sciences? A case study of Danish economics and political science. Scientometrics, 114, 1395–1421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2635-0

Hilmer, C. E., & Hilmer, M. J. (2005). How do journal quality, co-authorship, and author order affect agricultural economists’ salaries? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87(2), 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8276.2005.00738.x

Huang, W. (2015). Do ABCs get more citations than XYZs? Economic Inquiry, 53(1), 773–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12125

Hudson, J. (1996). Trends in multi-authored papers in economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(3), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.10.3.153

Jones, T. (2024). Hyphenating your last name after marriage. Marriage Name Change. Retrieved May 16, 2024, from https://www.marriagenamechange.com/blog/hyphenating-last-name/.

Kadel, A., & Walter, A. (2015). Do scholars in economics and finance react to alphabetical discrimination? Finance Research Letters, 14, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2015.05.015

Laband, D. N. (2002). Contribution, attribution and the allocation of intellectual property rights: Economics versus agricultural economics. Labour Economics, 9(1), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(01)00054-9

Laband, D. N., & Tollison, R. D. (2006). Alphabetized coauthorship. Applied Economics, 38(14), 1649–1653. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840500427007

Levitt, J. M., & Thelwall, M. (2013). Alphabetization and the skewing of first authorship towards last names early in the alphabet. Journal of Informetrics, 7(3), 575–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2013.03.002

Maciejovsky, B., Budescu, D. V., & Ariely, D. (2009). The researcher as a consumer of scientific publications: How do name-ordering conventions affect inferences about contribution credits? Marketing Science, 28(3), 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1080.0406

Nudelman A.E., Landers C.E. (1972). The failure of 100 divided by 3 to equal 33–1/3. The American Sociologist, 7

Oromaner, M. (1975). Collaboration and impact: The career of multi-authored publications. Social Science Information, 14, 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847501400113

Rudd, E. (1977). The effect of alphabetical order of author listing on the careers of scientists. Social Studies of Science, 7(2), 268–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631277700700208

Shevlin, M., & Davies, M. N. (1997). Alphabetical listing and citation rates. Nature, 388(6637), 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/40253

Van Praag, M., & Van Praag, B. M. (2004). First-author determinants and the benefits of being professor a (and not Z). Economica, 75(300), 782–796.

Van Praag, C. M., & Van Praag, B. M. S. (2008). The benefits of being economics professor a (rather than Z). Economica, 75(300), 782–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00653.x

Waltman, L. (2012). An empirical analysis of the use of alphabetical authorship in scientific publishing. Journal of Informetrics, 6(4), 700–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2012.07.008

Weber, M. (2018). The effects of listing authors in alphabetical order: A review of the empirical evidence. Research Evaluation, 27(3), 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvy008

White, K., Dalgleish, L., & Arnold, G. (1982). Authorship patterns in psychology: National and international trends. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 20, 190–192. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03334812

Yuret, T. (2016). Does alphabetization significantly affect academic careers? Scientometrics, 108(3), 1603–1619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2058-3

Yuret, T. (2019). A longitudinal analysis of the effect of alphabetization on academic careers. Data and Information Management, 3(2), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.2478/dim-2019-0006

Yuret, T., Oz, A. B., and Demir, G. (2023). ‘Sosyal bilimler alanında çalışan araştırmacılarının kendi yayınlarını öz değerlemesinden faydalanarak bilimsel değerlendirme yapılması’. TÜBİTAK 3005–121G161-(2023), Final Report.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Associate Professor Tolga Yuret, for his valuable guidance, knowledge, and suggestions during the preparation of this article.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). This research was supported by TÜBİTAK (The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey) under Project Number 3005-121G161-(2023). The funding source had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there are no conflict of interest associated with this research project.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Öz, A.B. Overcoming alphabetical disadvantage: factors influencing the use of surname initial techniques and their impact on citation rates in the four major disciplines of social sciences. Scientometrics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05100-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05100-5