Abstract

Coauthor and acknowledgment data were captured for 1384 research articles published between 1980 and June, 2023 that focused on tardigrades. Articles indexed in Web of Science or an archives of tardigrade literature were downloaded and thoroughly examined for personal acknowledgment data. Annual publication counts and coauthor maps for four successive time periods (1980–1999, 2000–2008, 2009–2017, 2018-June 2023) showed growth in the literature and increased research activity (more researchers, more complex networks, more international collaboration), beginning in 2000. A two-level Personal Acknowledgments Classification (PAC), was used to code types of acknowledgments. The majority of articles focused on field studies and/or descriptions of new species of tardigrades. This was reflected in rankings of acknowledgment categories and additions to the PAC. Ranked lists of frequently-thanked acknowledgees (all tardigrade researchers) were produced for each period. Acknowledgment profiles of four frequently-thanked researchers identified three different roles that researchers might play in tardigrade studies—”informal academic editorial consultant,” “taxonomic gatekeeper,” and “all-rounder.” Acknowledgments honoring people by naming a new species after them were only found in the species description, not in the formal acknowledgment section.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Studies of coauthorships, citations, and acknowledgments are three ways that metrics scholars have explored the ways that scholarship “works” and the ways that scholars show their indebtedness to others for a wide range of contributions. This is Cronin’s “reward triangle” (Costas & van Leeuwen, 2012; Cronin, 1995; Cronin & Weaver, 1995; Desrochers et al., 2016; Lou et al., 2023) including an author’s publications, citations, and acknowledgments in assessments. Coauthorships show contemporary connections and collaboration at the personal, departmental/institutional, and country levels. Citations connect documents, authors, institutions, and countries and can be used to trace information flows across time and geography. Acknowledgments of funding support link authors and their institutions with funding sources. Personal acknowledgments can show relationships among contemporaries and point to a range of sources of inspiration and support. Studies of personal acknowledgements in published journal articles can enhance our understanding of the ways that researchers interact with each other, giving and receiving materials and data, sharing methods, and providing useful suggestions and critiques of others’ work.

The research reported here is exploratory. It combines two of Cronin’s three “angles”—an overview of the changing formal collaboration structure of a field as represented by coauthor networks mapped over successive time periods and an analysis of acknowledgments made and received as indicators of the roles that others have played in the reported research. A detailed two-level classification of personal (non-funding) acknowledgments is used to profile the acknowledgment recipients (acknowledgees), many of whom are also included in one or another of the coauthor networks. In the analytical framework of Desrochers et al (2017), this research is “text-based” and “quantitative” (research type and method). The domain studied would be classed as “Biology” in terms of discipline (the most studied fields in acknowledgments research were Humanities, Social Sciences, and Clinical Medicine—Biology ranked 8th, just ahead of Chemistry and Physics). Based on the classification of McCain’s, 1991 article, this paper might be jointly theme-coded as Acknowledgment Centric and Credit and Illusio (given that a classification scheme and a major focus on “who-gets-thanked-for-what” are major features of the study), perhaps with a bit of Genre as well since there is some discussion of where in the document one should look to find acknowledgment statement.Footnote 1

In fact, one could add an additional phrase to the Credit and Illusio focus, since the present study explores not only “who-gets-thanked-for-what,” but also “by whom” (a point made in Desrochers et al., 2016, p. 235) and also add the “where” from Genre. The question is whether, by examining the text of the acknowledgement (wherever it is found), one can see the “who” and the “what,” connect these with the “whom” (authors listed in the byline), and, by summing over acknowledgments and time, determine if there are consistent “roles” that an acknowledgee has played in their interactions with the authors in the field.

There have been several reviews and useful overviews of the acknowledgments literature in recent years, including Baccini & Petrovich, 2022; Desrochers et al., 2017; Diaz-Faes & Bordons, 2017; Lou et al., 2023; Paul-Hus et al., 2017a, 2017b; Smirnova & Mayr, 2023b; Teixeira da Silva et al., 2023, and no attempt will be made to replicate those in this report. Rather, this section will examine current research using my modification of Desrochers et al.’s Credit and Illusio theme—”who-gets-thanked-for-what-by whom-and-where”.

WHERE are the personal acknowledgments?

There are two different aspects of WHERE—the sources used to extract and analyze acknowledgments and the location of that text in the source. In the case of the sources, most recent studies of acknowledgments have gone beyond the focused, hand-crafted journal-based studies by McCain, Cronin and others, using text-analytic tools and super-sized bodies of digital text. Web of Science (WoS) data and (in one case) Scopus data were most common (Baccini & Petrovich, 2022; Jia et al., 2023; Paul-Hus & Desrochers, 2019; Paul-Hus et al., 2017a, 2017b; Petrovich, 2021, 2022; Smirnova & Mayr, 2023a; Tian et al., 2021). A few studies examined full journal articles in digital form and used NLP software to extract acknowledgment text and acknowledgee names—data sets ranged in size from the 1.25 million papers downloaded from PubMed Central (Heo et al., 2023; Song et al., 2020; Xie & Zhang, 2023) to 428 K papers from open access journals (Kusumegi & Sano, 2022), 5 K papers in financial economics (Rose & Georg, 2021), and 2073 papers in analytic philosophy (Petrovich, 2021, 2022). McCain (2013, 2015, 2017, 2018a, 2018b) took a different approach to bounding a literature for analysis—retrieving articles that focused on the study of a particular model organism in the early years of the field from a variety of journals. The journal articles were identified by subject searching and the articles downloaded and read, beginning to end, to find acknowledgment text.

Consideration of the smaller WHERE—the location of the acknowledgments text in the article—took two forms. The WoS and Scopus studies mentioned above relied on the field in the database record that captured funding information for acknowledgment text. The issues with the WoS field are well known at this point. The text containing the financial support information is extracted and included in the database record and personal acknowledgment text is only included if it is in that same text block. Most journal articles combine the two kinds of acknowledgments these days, and most researchers seem to be content with that situation. It is unclear whether Scopus follows the same pattern but it’s a reasonable assumption. The studies that examined full journal articles and extracted acknowledgments text using NLP software seem to have focused on the “standard” location of that text—the title page or a block of text (labeled or unlabeled) at the end of the article (based on the journal’s guidelines) although Song et al (2020) looked for “footnotes and notes” as well as acknowledgement and funding text blocks. These studies are likely to have captured most or all the personal acknowledgments, depending on the subject area. In the biomedical literature, however, personal acknowledgments might appear only in the Methods & Materials section (McCain, 2018b), lowering the counts for some researchers if only acknowledgments in that standard section were tallied.

WHAT are people being thanked for?

Most studies that differentiate among different kinds of non-funding acknowledgments use some version of a single-level classification scheme which accounts for (1) research materials, resources, and data, (2) technical assistance, (3) clerical support/manuscript preparation, and (4) communication with research peers. This last was designated Peer Interactive Communication (PIC) by McCain (1991) and made very visible by Cronin in his studies of types of acknowledgments. When used as a framework for NLP extraction of acknowledgment data, researchers have included nouns and noun phrases to enrich the categories of interest (see e.g., Paul-Hus et al., 2017a, 2017b; Song et al., 2020). PIC appears to be the focal acknowledgment category in papers published in the humanities and social sciences, where formal presentation and commenting in conferences and the like are the bulk of the non-funding acknowledgments text (as contrasted to the sciences) and characteristic phrases are tallied (see, e.g., Economics–Baccini & Petrovich, 2022; Rose & Georg, 2021; Analytic Philosophy—Petrovich, 2021). The Personal Acknowledgments Classification (PAC) used by McCain (2018b and Appendix 1, this paper) has a detailed set of second-level categories for all but one of the classes. This allows a more specific tag of the contribution acknowledged. For instance, Peer-Interactive Communication is partitioned into five second-level categories in order to distinguish among comments on the manuscript, special thanks, general (unspecified) peer support and levels of detail in information provided.

Another view of acknowledgment structures and classification comes from the world of genre analysis. Hyland (2003, 2004) analyzed the content of dissertation texts and, after considering the content in terms similar to those discussed in the ‘standard” typology, proposed a classification based on rhetorical moves (Reflecting, Thanking, Announcing). Guščytė and Šinkūnienė (2019) adapted Hyland’s series of moves to classify acknowledgments in the journal literature of four disciplines—Biology, Robotics, Education, and Art History while retaining those of Hyland’s steps-within-moves that fit with the scholarly research literature.

Teixeira et al. (2023) discussed the value of acknowledgments in scholarly papers but noted the disparity in the guidance given to authors by the journals (unlike the CRediT system and similar accounting structures for itemizing author contribution) and pointed out ethical issues and the need for standardization of acknowledgments. While the focus of their paper is a review and assessment of journal policies and practices, the authors do discuss acknowledgment classifications, reviewing those used by Cronin (1995, 2001) and Song et al (2020). They indicate a preference for a 4-class system (funder/sponsor, moral support, technical and analytical support, and ideation support).

Another WHAT issue is whether the analyzed acknowledgment text should include information other that the traditional funding and expressions of personal gratitude, such as statements of compliance (conflicts of interest and adherence to mandated protocols) and ethical guidelines. Paul-Hus and Desrochers (2019) offer a set of 19 categories of acknowledgment content that include “conflict of interest,’ “disclaimer” (of responsibility), “ethics” (e.g., ethical approval of research), and “dissemination” (e.g., availability of data). These additional categories don’t appear to fit the notion of personal acknowledgments as currently studied since they are not really a statement of “thanks,” but it is likely that editors and readers would be reassured about the compliance of the research with current policies.

WHO is being thanked and by WHOM?

Taking a brief look at the current landscape of acknowledgments research since Desrochers et al (2017) and Diaz-Faes et al. (2017) published their reviews, it appears that studies that focus on acknowledgees are infrequent and those that examine the combined roles of author and acknowledgee are even more thin on the ground, when compared to the tallies of kinds of acknowledgments. As Desrochers et al (2017) note, the largest research theme in their review was Credit and Illusio which included any prior work on the roles of acknowledgees in the research process, the movement of many between the role of author and research supporter over time or from one paper to the next, and the general social context of research.

Much early work simply reported the WHO as a list of frequently thanked persons in a highly skewed distribution; some studies (e.g. Cronin et al., 2003, 2004) included contextual data such as institutional affiliation. More recently, studies of acknowledgees have included, in addition to institutional affiliation, PhD granting institution and prizes won (Baccini & Petrovich, 2022), acknowledging journals (Petrovich, 2021), network centrality scores (Kusumegi & Sano, 2022; Tian et al., 2021), alternative name forms and type and frequency of occurrence of acknowledgment categories (McCain, 2018b), and score in a proposed Acknowledgment Index (Heo et al., 2023).

Acknowledgees can be characterized by the types of things for which they are thanked. In the sciences a single person may, over the course of many papers, be thanked for a range of goods and services as well as various PIC interactions while others may only be thanked for one kind of contribution (McCain, 2018b). The acknowledgee’s connection to the author or their role in the research may be explicit (member of the research group, technical assistant, caretaker for the experimental organisms, editor of journal or section), but in other cases they are simply thanked for comments, or for providing information or research materials, and discovery of any formal or informal connections is left to the researcher. In some subject areas where acknowledgments are studied, almost all the acknowledgments seem to be categorized, explicitly or by description, as PIC. In economics, the role of “commenter” (discussant of a paper delivered at a conference) is most commonly an explicitly assigned role, generally by the session organizer.Footnote 2 The author is expected to provide the commenter a copy of the paper in advance and a grateful acknowledgment down the road; for an active author, the list of names and presentation venues can be extensive (see, e.g. Baccini & Petrovich, 2022; Rose & Georg, 2021). Petrovich (2021) gives a similar example of an acknowledgment text in philosophy where many individuals as well as the general “audience” are thanked for “constructive feedback” and “important comments”—they are all, in a sense, “commenters.”

Several articles examine the relationship between paper authors (acknowledgers) and acknowledgees using network analysis. These are generally two-mode directed networks, with the nodes representing authors (or papers which may have any number of authors) and acknowledgees; the link between two nodes represents the acknowledgment made from an author/paper to a recipient. The resulting network (or networks if data are collected over separate time spans) can be seen as evidence of knowledge flows from acknowledgee to author, informal communication (in contrast to coauthor networks), or evidence of an invisible college. Tian et al (2021) created both acknowledgment and collaboration (coauthor) networks based on data recorded in Web of Science records in the general area of wind energy, an “Acknowledgee Network” connected all paper authors with acknowledgees, noting that some authors played both roles—as an author in some papers and an acknowledgee in others. Using regression analysis and network statistics, Tian et al. concluded that acknowledgees’ centrality in their network had a positive effect on citation count of the articles analyzed, while the authors’ centrality negatively moderated that relationship. Fahmy and Young (2015) created a PIC network based on journals in Criminology and Criminal Justice where all acknowledgees were students or faculty members and had also authored at least one article in the data set. They found one giant component comprising 55% of the nodes and discussed the existence of a network of “invisible colleagues.” Similarly, Kusumegi and Sano (2022) built a network connecting authors and acknowledgees who were identified as “acknowledged scholars” (based on data from Microsoft Academic Graph), noting that a node could be both an author and an acknowledgee. No network is shown, but they report network statistics, the names of the 10 scholars ranked by in-degree value (number of inbound links), and the 10 with the highest acknowledgment count. Rose and Georg (2021) built coauthor and author/commenter networks for articles published in 6 financial economics journals over two time periods—1997–1999 and 2009–2011. Most of the reported results are network-level measures, but they do show the (sparse) coauthor and (dense) author/commenter networks and report the prevalence of reciprocity among commenters. Baccini and Petrovich (2022) identified a “hierarchy of acknowledgment,” identifying various clusters of scholars, including one containing authors who never made an acknowledgment (authors only), one containing acknowledgees who were only acknowledged by authors who were themselves not acknowledged, and one containing authors who acknowledged others who did not reciprocate.Footnote 3

The author (or paper) and acknowledgee two-mode networks can be decomposed, with interesting results. In his study of acknowledgements in analytic philosophy, Petrovich (2022) included a two-mode network (papers × acknowledgees) and two derived networks—a network of papers linked by shared acknowledgees (parallel to a network based on bibliographic coupling of papers) and a network of co-mentioned acknowledgees (parallel to a document co-citation network). Examination of these two pairs of networks allowed him to compare the intellectual structure (based on citation data) and the social structure (based on acknowledgment data). The citation-based networks showed more clearly-defined subject clusters than the acknowledgment networks, with the latter having two undefined clusters and a distribution of epistemologists throughout the network.

Background of this research project

The research reported here had its beginnings in a paper (McCain, 1991) that modeled three ways in which researchers might learn about and request Research-Related Information (physical research products and novel research techniques). The models were based on a series of interviews with geneticists and enhanced by an analysis of acknowledgments for various goods, services, and information in 1 year’s articles in the journal Genetics. A primitive 5 class, two-tiered classification of acknowledgment statements—the goods, services, or information being provided—accompanied the main results. A second paper (McCain, 1995) reviewed the issues surrounding “sharing,” and examined the “instructions to authors” in a range of life science, medical, and engineering journals to see to what extent sharing of materials was expected. Only 16% of the journals examined had at least one policy statement concerning deposition of data or research materials or making information available in supplementary publication.

As noted in the previous section, acknowledgments research has tended to focus on specific journals in various subject areas—either through direct examination, by extracting relevant information from the Web of Science, or by searching broad subject areas in WoS and examining the journal records retrieved. In terms of the personal acknowledgments and their recipients, the results tended to be presented as highly skewed ranked lists, whether the data set was based on one journal or a large body of work. Types of acknowledgments are reported in broad single-level classifications (the hidden diversity may be more of an issue in the sciences than the examples offered from economics and philosophy). So I sought an alternative approach.

Restricting the document set to a very focused topic such as research on a particular model organism (rather than a collection of journals in one broad subject area) and applying a more detailed acknowledgment classification scheme (rather than the single-level scheme in general use) seemed to hold promise. Model organisms (e.g., fruit flies, mice, roundworms) have been bred to facilitate the study of a wide range of biological phenomena, from increasing our understanding of evolution to specific questions in human biomedicine (Ankeny & Leonelli, 2011). Model organism research generates an infrastructure with an identifiable social structure among researchers, the establishment of stock/strain centers (research organisms), community databases (information and published research about the organisms), and a community ethos (e.g., sharing materials and information). Examining coauthor and acknowledgment patterns in the early years of research on a specific model organism could be useful in exploring the ways that new research areas develop and assess the contributions made by frequently thanked acknowledgees (who may also have been authors in other papers).

Three studies published between 2015 and 2018 presented the analyses of model organism literatures using time series mapping of coauthor networks and personal acknowledgments in the journals—a sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis), a primitive plant (Physcomitrella patens), and the early years of research on the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Take-aways from these studies include:

-

The highly-ranked types of acknowledgments were typical of laboratory-based research (research materials and organisms, technical assistance, interaction with colleagues)

-

Researchers in one study (2018a) almost never thanked anonymous researchers, they were frequently thanked in the other two studies.

-

Differences in acknowledgment practices could be seen at the level of the individual laboratory (often identified by well-connected coauthor networks with a central author). One lab always thanked the assistant who maintained the experimental organisms, another never did; one lab would always acknowledge the “anonymous reviewers,” another didn’t (2015).

-

Acknowledgments can be found in the Methods & Materials section of the journal articles, sometimes thanking people who were not mentioned in the standard section. The potential difference in acknowledgment count can be as much as 25% (2017, 2018a).

-

High acknowledgment tallies do not necessarily point to researchers in the field of study—some highly ranked names may be skilled technical support staff or researchers in other fields whose only role is to serve as a source for specific research reagents (2018b)

-

The researchers who are most central to their networks (heads of labs) may be highly cited, but acknowledgments may come exclusively from authors outside of the laboratory network (2018a).

During this same period, the Personal Acknowledgments Classification was more fully developed, being enriched by the wider variety of things for which people were thanked.

This current project casts a wider net than a study of a single species as a model organism (more journal titles, more organisms) but still maintains a central focus by studying research at the level of the single phylum—the highest, most general level of taxonomic classification. The group chosen is the phylum Tardigrada (also known as water bears or, rarely, moss piglets). Advantages of choosing this topic include a literature of manageable size in terms of total publications in the past 4 decades and many of the same features seen in model organism research, including a strong social and collaborative structure and a range of community resources. There have been international triennial tardigrade conferences since 1974 (in Italy), the most recent being 2022 in Poland. Since 2012, the international research community has been supported by a two-part website (Tardigrada.net) (Michalczyk, 2023a), consisting of the Tardigrada Newsletter, that serves both as a repository of papers published since 2001 and contact details for tardigradologists, and the Tardigrada Register, “graphic, morphometric, molecular and zoogeographic data on Tardigrada species in order to facilitate their taxonomic identifications” (Michalczyk & Kaczmarek, 2013). For 2023, in honor of the 250th anniversary of the discovery of tardigrades, Dr. Ralph O. Schill organized a series of monthly online presentations on various aspects of tardigrade research; it had an initial subscribed audience of 126 participants from 25 countries.Footnote 4 The online presentations were recorded and made available for a month after presentation.

Tardigrade research covers a broader range of topics than the earlier lab-based model organism studies. There are roughly 1500 species of tardigrades known to date, but new tardigrade species are reported every year, based on a combination of DNA analyses and detailed morphological description. In addition, there are many reports of known species in new geographic locations and environments (McInnes et al., 2021). While tardigrades are perhaps most studied for their various environmental adaptations (being able to survive extreme desiccation, very low temperatures, and high levels of radiation) there is ongoing research on all aspects of their biology (see Miller, 2011 and Schill, 2018). As the results will show, moving to the phylum level—but keeping to a phylum with a relatively small footprint—expanded the view of life sciences research that could be captured by studying acknowledgments, further enriched the PAC, and provided an interesting view of the complementary roles of researchers as coauthors and acknowledgees.

Limitations

Until 2001 (the earliest articles in the archives of the Tardigrada Newsletter), data gathering was restricted to the Web of Science coverage of the topic, with anticipated results (missing journal years and individual issues as well as non-coverage of useful state, regional, and national science journals).Footnote 5 Searches covering the years 1980–2000 are likely to have missed a few publications.

Methods

Data sources

Articles for analysis were retrieved from two sources—Web of Science (1980-June 2023) and the archives of the Tardigrada Newsletter (2001-June 2023). These two sources required slightly different processing:

-

WoS search. The fields TOPIC or TITLE or AU KW or KW + (currently AK and KP tags) were searched for terms relating to tardigrades. Search terms included variants of “tardigrade” and “water bear” and the classes Eutardigrada, Arthrotardigrada, and Heterotardigrada. Post-retrieval screening criteria included elimination of (1) all papers relating to the extinct giant sloths and one species of slow loris (Tardigrada is an obsolete order in the class Mammalia); (2) papers including more than one additional taxon (these tended to be field surveys or higher-level taxonomic discussions not focusing on tardigrades themselves); (3) papers that mentioned tardigrades in passing but were really focused on something different.

-

Archives search. The initial screening is naturally done by the researchers submitting papers to the archives—no giant sloths. But the other screening criteria were applied.

Data collection

All relevant papers were downloaded in full-text. The standard metadata (number of authors, authors’ names, addresses, publication date, source data, abstract if available, and acknowledgment text (both funding and personal acknowledgments) were extracted from the articles (copy/paste—no automated text identification or extraction) and entered into a Filemaker Pro database. Additional fields were added. These included.

-

Where the article was found (WoS, Archive, or both)

-

Code for the first occurrence of each acknowledgment class (initially based on the PAC published in McCain, 2018b). In analyses, all acknowledgees were credited with their full set of acknowledgments from the article text. Revisions to the classification were made as needed (see Table 2, Appendix 2, and discussion)

-

Names of acknowledgees (and where found in the text)

-

Taxonomic content (announcement of a new taxon or revision of an existing taxon).

-

Basis of name for new taxon and taxon name category (another classification scheme, available upon request).

Authors’ names were regularized to a single representation. This was done using author publications, researcher information in the Tardigrada Newsletter, and authors’ personal or laboratory websites.

Data analysis

General statistics

-

Annual publication data are represented as a bar chart, with each bar partitioned to represent the number of articles with or without taxonomic content (e.g., announcement of new taxa).

-

Frequency-ranked lists of acknowledgments by type and acknowledgees by frequency and type were compiled from the data in hand as were tables reporting detailed acknowledgment profiles for selected tardigrade researchers.

Coauthor maps

Pairs of coauthors in both positions (1st, 2nd in pair) were extracted by hand from each article and repeating pairs tallied across each time period. The list of coauthor pairs, ranked by frequency was submitted to UCINET6 (a social network analysis program) and NETDRAW (a network visualization package embedded in UCINET6). For this report, a weight (frequency of coauthor pairs) of 4 articles coauthored over the time period was used, except in the 1980–1999 period where both 3 and 4 + thresholds are examined. In the maps, tagging by country was based on the authors’ most frequent location for that time period, as shown in their bylines.

Results

Overviews

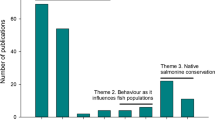

Figure 1 shows the growth in the tardigrade literature between 1980 and June, 2023. The dataset of 1384 articles is partitioned into 4 time periods: 1980–1999, 2000–2008, 2009–2017, and 2018-June 2023.Footnote 6 For each year, the vertical bar shows the number of articles announcing one or more new taxa (most commonly a new species of tardigrade) (pattern fill) and the remaining number of articles (solid fill).

Tables 1 and 2 present data for the entire time period. Table 1 lists the top 19 journals ranked by number of articles included in the data set.

Table 2 shows the top 15 acknowledgment categories occurring at least once in a journal article over the years 1980–2023. One new category (1g Reference materials) and two glossed categories (3d Special thanks (etymology) and 1c Equipment & facilities (collection) were added to the PAC as a result of the large number of taxonomic-related articles, either announcing new taxa named after a person (a special honor), thanking someone for providing materials needed to identify organisms in hand, or thanking someone for making a collection of tardigrade specimens accessible for examination. For comparison with an earlier study of the zebrafish literature (1995–2004, see McCain, 2018b), the top 5 acknowledgment categories in that study are italicized in Table 2.Footnote 7

Results for 4 time periods

The focus of this study is the collaboration structure and acknowledgment patterns in the tardigrade research literature over four successive time periods (see Fig. 1). In this section, results are given separately for each time period. In each map, the coauthors are nodes, connected by edges whose weight represents the number of shared bylines; the thicker the line, the more times the two authors shared a byline. The lower cutoff is 4 + bylines for three of the four maps; in Fig. 2 (1980–1999) additional authors sharing three bylines are added. Node size is based on degree centrality of the authors in the network and the networks are labeled by country affiliation based on author addressFootnote 8 (additionally, node color and shape are used to highlight the most frequent country affiliation). Tables report the top acknowledgment categories and top acknowledgees for each time period, ranked by the number of articles. The counts represent at least one occurrence per article, with the exception of the names of persons honored by having a new taxon named after them. Appendix 3 presents a direct comparison of the acknowledgments in rank order for each time period (the counts are not shown for reasons of space/readability).

1980–1999

Figure 2 shows the coauthor network for 1980–1999. Authors in dashed circles share only three bylines with the other authors in their network. The remaining author connections have a weight of 4 + shared bylines (Tables 3 and 4).

2000–2008

See Fig. 3 and Tables 5 and 6.

2009–2017

See Fig. 4 and Tables 7 and 8.

2018–2023 (June)

See Fig. 5 and Tables 9 and 10.

Acknowledgment profiles for 4 author/acknowledgees

Tables 11, 12, 13, and 14 present research profiles and detailed acknowledgment data for three selected tardigrade researchers who were listed in all four Acknowledgee tables and a fourth who is one of the most prominent researchers in the last two. The top 2 (or 3 if there’s a tie) acknowledgment categories are shown for each time period, labeled based on the frequency of the acknowledgee coauthoring at least one paper with one of the authors in the paper containing an acknowledgment in that category.Footnote 9 The total number of articles containing at least one acknowledgement is in brackets after the date range.

Discussion

From the lab to the field

The earlier studies in collaboration and acknowledgments in the life sciences focused on the literature generated by research on various model organisms in the expectation that the set of articles would be more coherent and interrelated than those extracted from one or a few topical journals or a subject search in WoS. For the most part, the expectations were met. Time series of coauthor networks in the model organism studies show the development of the fields as sets of networks representing a range of configurations—from pairs of authors at the same or different institutions to author networks in single laboratories and multi-laboratory networks. The two-level PAC allowed a detailed look at the range of goods, services, and information provided. The various scientists (many of whom were also authors in the networks) and staff who were being thanked could be connected with specific kinds of PIC, for instance, or greater detail in sharing of the research materials and technical support than was possible when using the single level classification popularized by Cronin’s work. In addition, careful reading discovered acknowledgments in the Methods & Materials section of articles as well in the standard text section.

However, model organisms are maintained and research is conducted in the laboratory, and the results reflected this (see esp. McCain, 2018b and Appendix 2). The tops of the ranked lists of acknowledgment categories were replete with laboratory-relevant goods and services. The research reported here, based on the literature in tardigrade research, was a first exploration of life sciences acknowledgments behavior beyond the lab. Many different species of tardigrades were being collected from a wide range of geographic locations (every continent including Antarctica) and ecological conditions (land and water, deserts to mountains) rather than genetically identical organisms being acquired from a colleague’s laboratory, stock center, or supply house.

Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2 show the most striking differences between lab and “field.” The first is the importance of taxonomy and systematics in tardigrade research.Footnote 10 All but a few of the publication years between 1980 and June 2023 included at least one paper describing a new species of tardigrade, a new genus, or a revision of existing taxonomy with name changes. Many of the remaining papers were reports of known tardigrades being found in new locations (a standard part of natural history research). Over the years, an increasing number were reporting research on tardigrades in the lab—studies in reproduction, biochemistry, physiology, behavior, etc. The percentage of taxonomic articles in the journals in Table 1 reflects this with a few journals publishing mostly taxonomic articles and others covering a wider range of research. In Table 2, we can see additional evidence of the importance of taxonomic research and the contributions by acknowledgees, all of whom are also authors in the collaboration networks. The category of 1g Reference materials had to be added to Class 1 (Research materials) to account for specimens (preserved tardigrades) or microphotographs lent to the requester by another researcher (or a collection) for comparison to an unknown tardigrade in hand.Footnote 11 If the requester was granted permission to visit a collection and view the specimens there, the acknowledgment was classed as 1c Equipment & facilities (collection). If a new species was named after a person, that special recognition was classed as 3d Special thanks (etymology).

Just as the Methods & Materials section of zebrafish papers contained acknowledgments not echoed in the end-of-article acknowledgment block (McCain, 2018b), so taxonomic articles naming a new species of tardigrade to honor someone only put that information in the Etymology section of the formal species description. Again, the article had to be read thoroughly to find this information.

The acknowledgment categories in Table 2 and Appendix 2 show a range of effects of shifting from the lab to the field. Collecting the tardigrades for current or future research (they can be maintained in a kind of suspended animation for years, even decades) is an important contribution and is acknowledged (and the collector occasionally honored by naming the new species after them). 4e Collecting organisms ranked near or at the bottom of model organism ranked lists if it existed at all. Conversely, 1b Research materials (which are things used up in laboratory research) moved way down the ranks from its position in the model organism studies, as did 4d Technical assistance, again, more important in model organism lab research. 1c Equipment & facilities remained an important acknowledgment category, but the emphasis is on equipment like phase contrast and scanning electron microscopes and, in the post-2004 articles, apparatus for DNA analysis.

Time-series results—Coauthor maps

Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 show the development of tardigrade research from 1980-June 2023. The most striking feature is the increase in authors and associated increasing membership in existing networks and appearance of new networks—especially when the threshold of 4 + shared bylines is maintained across all four time periods. The maps are presented primarily to provide context for the analysis of acknowledgments; the highlights are reviewed below.

The first 20 years (1980–1999) combines views at the 3 and 4 + thresholds in order to give some idea of the collaboration structure in a data set with less than half of the published papers over twice as many publication years. Research (as represented by publications) was focused in the US (2 networks) and Italy (3 networks); the 3-byline connection between Nelson and Bertolani is the more substantive international collaboration.

Over the following three time periods, we observe the noticeable rise both in annual publications and in an increase in European and Asian (primarily Japan) participation in tardigrade research.Footnote 12 An increase in collaboration between North America and Europe can be seen as well. Some features are:

-

Italy: We can see connections between the Bertolani group (University of Modena & Reggio Emilia) and the Pilato/Lisi group (University of Catania) and increased international collaboration between the latter and groups from Portugal and Colombia in 2009–2017. In the last time period, only the Bertolani group is visible at the 4 + byline threshold.

-

Portugal: In 2018–2023 the Portuguese triad (Fontoura, Viega, Rubal), formerly connected to Pilato and Lisi, now links with Bartles (US) and a set of researchers based in Argentina.

-

Poland: Two Polish tardigrade researchers, Kaczmarek and Michalczyk, appear first as part of a triad with C. W. Beasley, then as two anchors of a large network with byline links between Kaczmarek and Frohme (one author in a German network) and finally as a pair anchoring different complex subnetworks in 2018–2023.

-

US: Tardigrade research in the US waxed and waned. Nelson and Bartels, a dyad in 2000–2008, became visible collaborators with Kaczmarek in 2009–2017, as did W. R. Miller and Perry in 2018–2023. The Goldstein laboratory at the University of North Carolina was visible and active in 2009–2017 (papers included evolutionary models and studies on the biochemistry and physiology of stress tolerance); in the last time period, only a triad of researchers (Mehta, Pielak, Piszkiewicz) appears at the 4 + byline threshold. Miller, Perry and Kaczmarek coauthored four articles on abbreviations of the names of tardigrade genera.

-

Denmark: The early dyad of Kristensen and Jorgensen expanded and then separated, with Kristensen collaborating with the Michalczyk subgroup and the remainder as a triad of Neves, Mobjerg and Jorgensen.

-

Japan: Tardigrade research in Japan appears in the 2000–2008 map with a single coauthor network, expanding to two in the remaining two time periods. Above the coauthor threshold, there is no visible international collaboration between Japanese and European or US researchers. Atsuki C Suzuki (Keio University) has collaborated separately with both Japanese and European/US researchers, but no collaborations reached the 4-link level. The next tardigrade symposium will be held in Japan in 2025.

Exploration of the possible reasons for the rapid rise of tardigrade research and the large and complex networks in Europe is beyond the scope of this paper, which focuses on the collaborating authors as both senders and receivers of acknowledgments. But two things might be considered when planning such a study: first, taxonomy and systematics research has been seen as under threat for decades in terms of educational opportunities and research funding (Agnarsson & Kuntner, 2007; Britz et al., 2020; Ebach et al., 2011) and US research may have been more affected than research in Europe; second, the better funded and technology-rich laboratories may offer collaboration opportunities for researchers in less well-funded situations (e.g., collaboration for DNA barcoding in submitting new species description, Michalczyk, 2023b) which would increase publication.

Time series results—acknowledgment categories

There is relatively little change in the top acknowledgment categories from one time period to the next. 3b Comments on manuscript is the top-ranked category across the board, with 1g Reference materials, 4e Collecting organisms, and 3a Specific information or suggestion occupying the next four places in one order or another.Footnote 13 The combination of these three categories shows that an emphasis on taxonomy, systematics, and biogeography (what is this tardigrade and/or where was it found) persists throughout. Most of the papers fall into this general topic area, although laboratory studies on the biochemistry and physiology of tardigrades grew substantially in more recent years as they became more biomedically relevant and research proposals attracted funding. A quick examination of the 2018–2023 data shows that “tardigrade in the lab” articles constitute about 1/3 (140) of the 431 articles in the data set when those dealing with taxonomy, systematics, and field studies (tardigrades found in a new location or ecological habitat), inventories, and check lists of tardigrades are removed. What remains is a combination of laboratory studies of tardigrade reproduction and development, behavior, and (most importantly for biomedicine) studies looking at the biochemistry and physiology involved with tardigrade cryptobiosis (a reversible metabolic state where the animals respond to extreme cold, desiccation or other environmental stresses by essentially shutting down their metabolism). If we look at the top six acknowledgment categories for these articles ), they look much more like the italicized acknowledgments from the (Table 15), they look much more like the italicized acknowledgments from the zebrafish data seen in Table 2 and high-ranking acknowledgments in Appendix 2—research materials, technical support, and equipment & facilities in addition to comments on manuscript.

Time series results—acknowledgees

Unlike the series of acknowledgment category rankings, the rankings of acknowledgees change from one time period to the next. Except for the first time period (where they rank 5th out of 8), “anonymous reviewers” ranks first in the personal (non-funding) acknowledgments (and are always coded as 3b Comments on manuscript). Most of the named individuals in each table are authors in one or another of the coauthor maps (bearing in mind that there is a threshold for coauthorship and authors who primarily publish without coauthors won’t be in the maps at all). Four acknowledgees are listed in all four tables: Diane Nelson, Roberto Bertolani, Reinhardt Kristensen, and Giovanni Pilato. The latter three have laboratories, multiple in-house colleagues, and graduate students, while Nelson has been a solo researcher at her college, collaborating with Paul Bartels (US) and many tardigradologists in Europe.

We should note that ranked acknowledgees may not be active researchers and authors. It’s reasonable to assume that, unlike citations, personal acknowledgments are primarily contemporary with the people who are thanked (with the obvious exception of valedictory statements and the like). In Table 4, Walter Maucci (1922–1995) is 6th in the ranked list. He only had one published article in the data set but was a very well-known tardigrade taxonomist over several previous decades. In 1980–1999, Maucci is thanked by various active researchers for loaning specimens and providing advice and comments on manuscripts. Between 1998 and 2023, some years after his passing, he is still thanked by Giovanni Pilato in 13 articles for sending specimens for a tardigrade collection.Footnote 14

Acknowledgees need not even be tardigrade researchers. In the 1995–1999 zebrafish data set (McCain, 2018b), a research associate was in the top 12 acknowledgees (primarily for specific analyses) and in 2000–2004 a non-zebrafish researcher ranked in the top 20 and was thanked for research materials (antibodies). In Table 6 of the present study, Magowski (apparently not a tardigrade researcher) is thanked in 19 of 23 papers for making a phase contrast microscope available and thanked for comments in the remainder (Kaczmarek was an author on all 23 papers, Michalczyk on all but 2). In the exploration of the “tardigrades in the lab” paper subset (Table 15), Dr. Danuta Urbanska-Jasik was thanked for her technical expertise in 8 papers written by Izabela Poprawa, both at the University of Silesia (Katowice, Poland).

Acknowledgment profiles—connecting WHO, WHAT, and from WHOM

One of the goals of this current project was to drill down to the finer acknowledgment details of WHO, WHAT and from WHOM and look for differences between acknowledgees that would suggest a particular part that they might play in the tardigrade research community. The first issue one meets is the definition and breadth of WHAT is being acknowledged. As noted earlier, most acknowledgment studies that deal with WHAT categorize the acknowledged goods, services, and information using a variant of Cronin’s 6 class/one level scheme (see, e.g., Cronin & Franks, 2006—Financial, Materials, Technical assistance, Conceptual (which includes PIC), Organizational, Manuscript preparation). The single-level scheme is a pretty blunt instrument if one wants to get a good appreciation for the “gift exchange” activities in the life sciences. For instance, the first-level class Peer-Interactive Communication, popularized by Cronin and which many acknowledgment researchers focus on, includes a variety of “gifts” in the current classification scheme (titles only–see the PAC in Appendix 1 for full documentation and cross-category references).

Category 3: Peer-Interactive Communication (PIC).

3a. Specific information or suggestion

3b. Comments on manuscript

3c. Advice & discussion

3d. Special thanks

3e. Peer support

PIC as a category has been treated in diverse ways in acknowledgment studies. Studies of acknowledgments in the humanities and social sciences seem to allocate most if not all personal acknowledgments to PIC (see, e.g., Baccini & Petrovich, 2022; Petrovich, 2021) since people are being specifically thanked for comments made in formal presentations (symposium, seminar, etc.). In this study, 3b Comments on manuscript is certainly the highest-ranked category in Table 2, but we also see 3a Specific information or suggestion ranked 3rd and 3d Special thanks (etymology) ranking 6th (assigned whenever a new taxon is named for a person). The remaining two categories rank 9th and 10th in this study. Lumping them all under the PIC rubric would be less than informative. The categories in Class 1, which deals with resources and Class 4, which deals with technical assistance, are similarly diverse (see Appendix 1) and would lose a great deal of useful differentiation if relegated to the single overarching classes (Research materials and Technical assistance, respectively). Two studies, Paul-Hus et al., (2017a, 2017b) and Song et al (2020) seemed to recognize the range of topics by using a variety of noun phrases (but mapped all retrievals to the higher-level class). Paul-Hus, Diaz-Faes et al. separated technical support and peer discussion, showing subject word clouds using correspondence analysis, while Song et al. combined the two categories as “peer interactive communication and technical support,” including rules for category content and references to prior research in an appendix.

Another issue in connecting WHO & WHAT with from WHOM is defining the WHOM. It’s reasonably straightforward to build a network linking the individual papers with the acknowledgees listed within the papers. The connection is between WHO (as individual acknowledgees) and from WHOM (as a byline package), but the connecting WHAT is not explicitly included (see, e.g., Petrovich, 2022). Studies that link all individual paper authors with all individual acknowledgees in their papers face a similar but messier problem since there no sensible way (except in the relatively rare case of single-authored papers and all acknowledgees recognized for the same thing) to build in the WHAT. This doesn’t appear to be as much of a problem in the studies of acknowledgments in economics and philosophy—with all acknowledgments being essentially the same thing, the link must be understood directly as comment received and thanks given.

I’ve tried to address this in a different way in Tables 11, 12, 13, and 14. Most papers in the life sciences have multiple authors (the mean in this study is 3.4 authors/paper).Footnote 15 Instead of mapping individual authors to acknowledgees and trying to somehow code the link between them as representing one or another of the 2nd-level acknowledgment categories, the data as shown omit the names of the paper authors (acknowledgers) in favor of highlighting the category of each acknowledgment made by the set of paper authors as a whole. The connection is whether the profiled acknowledgee (who is also an active tardigrade researcher) has coauthored elsewhere with at least one of the authors of each acknowledging paper (paper authors rarely also thank themselves in the acknowledgments sectionFootnote 16). It is not necessary for the acknowledgee being profiled to have coauthored with all of the authors of the acknowledging paper—a single coauthor from the byline in at least one paper is sufficient to create a link.Footnote 17

The four categories shown are.

-

Never coauthored with one of the thanking paper authors (in that time period),

-

Infrequently coauthored (1–2 papers)

-

Frequently coauthored (3 + papers)

-

Laboratory colleagues (which implies a different relationship between the author and acknowledgees as coauthors).

The count is the number of papers falling in each of the 4 categories and serves as an indication of the strength of collaboration/connection between the acknowledgee and those authors who are thanking them.

One can easily see how an acknowledgment relationship and coauthorship elsewhere might march together. A great deal of communication goes on in the average laboratory or similar research venue—presentations with comments, reading early manuscript versions, sharing ideas, working out problems, etc. The profiled acknowledgee just didn’t participate in the research reported in those particular papers but did in other papers—more or less often. But how to account for acknowledgments from authors when the profiled acknowledgee publishes without coauthors (or at least never coauthored with any of the authors making the acknowledgment and is not in the same institution)?

Several scenarios come to mind:

-

The person thanked is a “standard” source or the only source for the research materials/experimental organisms or information and this is known to the requester. We saw that in the last section where one non-zebrafish researcher was clearly the source one went to for specific antibodies. One would also see this when experimental organisms (e.g., fruit flies with a particular mutation) are requested from someone who maintains their own stocks rather than requesting materials from a stock center or commercial supply house (McCain, 1991). In tardigrade taxonomic research, the holder of a particular holotype or paratype is the one to ask when one wants to borrow the material (specimen or microphotograph) or request access to the collection that holds the specimens. There is no other source (although other researchers may have their own well-curated collections and will lend well-identified specimens). The lender will often provide taxonomically-relevant information as well (and be thanked for that separately, coded as 3a Specific information or suggestion).Footnote 18

-

The person thanked is the editor of that journal or journal section. No prior familiarity is required, only being the author(s) of a paper that is under review.

-

The paper author(s) and acknowledgee meet in a research-oriented environment and become acquainted. In the case of tardigrade research, the triennial tardigrade symposium offers researchers from around the world opportunities to meet, obtain input on their research, share ideas and information, and plan future collaborations.

The four researchers in Tables 11, 12, 13, and 14 appear to have somewhat different profiles based on the top acknowledgment categories and the degree of connection between the research and the authors thanking them for various things.

-

Diane Nelson is thanked primarily for providing useful editorial and content-relevant input—3b Comments on manuscript and 5c English editing (which is more likely to be suggestion on improvements rather than the complete job that a professional editor would doFootnote 19). In the earlier time periods she is more often thanked for comments by authors with whom she has no shared bylines (N). This shifts over time and in the latter two time periods her comments are on papers written by authors with whom she has published. Suggestion on improving the English prose follows a similar pattern, from thanks by authors with whom she has some connection (I) to authors with whom she is a frequent coauthor.

-

Roberto Bertolani is most frequently thanked for lending taxonomic specimens (1g Reference materials), taxonomically-relevant information (3a Specific information or suggestion), or providing access to existing tardigrade collections in situ (1c Equipment & Facilities (collection). Most of these requests were from authors with whom he had an infrequent or no coauthor relationship. He also commented on manuscripts written by laboratory colleagues (3b Comments on manuscript) in the 2009–2017 time period.

-

Reinhardt Kristensen’s profile has some similarities to Bertolani’s in that he has served as a source for reference materials (1g), primarily from researchers with whom he has little or no connection. But he also resembles Nelson’s profile in that he frequently comments on manuscripts written by relatively non-connected authors and (in the earliest time period) he, Nelson, and Bertolani were all frequently thanked by this same category of authors for specific information (3a). Interestingly, he is the only one of the four profiled who was thanked for collecting tardigrades in the wild and sharing them (4c) by his otherwise frequent coauthors (in all of the five articles he was one of several to many people thanked for their contributions to broad biogeographic studies).

-

Łucacz Kaczmarek’s profile falls in between Kristensen’s and Bertolani’s over the latter three periods. All three were providers of tardigrade specimens (1g), specific information (3a), and comments on manuscripts (3b). In the most recent period (2018–2023), he was thanked by more of his coauthors for reference materials than by authors with few or no connections.

Most prior studies seem to have focused on connecting two of the three:

-

WHO & WHAT. Results may be presented as ranked lists of acknowledgees and what they are thanked for (e.g., McCain, 2018b). Heo et al (2023) itemized acknowledgment content for one researcher and reported a calculated “Acknowledgment Index” score for 29 top acknowledgees but did not discuss any topical profiles.

-

WHO & from WHOM. These studies show the data as networks linking papers/authors and acknowledgees. The only indication of WHAT links the two is the consideration only of acknowledgments that fall into the PIC category. As noted earlier, this would include economics and philosophy, where the acknowledgment text only refers to commenters on papers presented at a conference or seminar (Baccini & Petrovich, 2022; Petrovich, 2021, 2022; Rose and Georg 2021).Footnote 20 Fahmy and Young (2015) mapped articles and acknowledgees in an explicitly designed but generalized PIC network. Tian et al (2021) report the degree centrality of the top 20 acknowledgees in the field of “wind energy. “ They describe these as the most “influential” scholars in the acknowledgment network but do not categorize the categories in which the acknowledgments fall. Rose and Georg (2021) rank coauthors and commenters by name on different network centrality measures, but nothing else. Baccini and Petrovich (2022) cluster scholars (both authors and acknowledgees) by inter-cluster acknowledgement links (the connections are all commenting relationships).

-

WHAT & from WHOM. This kind of study would focus on individual named authors and the kinds of acknowledgments they make, but not mention the recipients of the acknowledgments. For example, Desrochers and Pecoskie (2014) published a study of authors whose books received the 2010 Canadian Governor General’s Literary Awards. Their results include tables listing the individual authors and books but only reporting various types of (unnamed) individual and community information sources. Kantha (2017) studied acknowledgments made in papers written by Frances Crick (Nobel laureate) and reproduced the acknowledgments text for each article, followed by a brief analysis grouping acknowledgees by acknowledgment type.

Two model organism studies (McCain, 2015, 2018a) attempted to address the triple connection in different ways. McCain (2015) focused on acknowledgment categories while reducing the identity of acknowledgment makers and receivers to coauthors within and outside identifiable networks; acknowledgment counts were tallied as made from members of an individual extended research group (a collegium) to others in the same collegium (including general thanks to members of the laboratory), members of the broader coauthor network, other coauthor networks, or those outside the network entirely (including anonymous reviewers). However, none of the participants were named (except for the central figure in each collegium) and, in essence, one had a WHAT with a very generalized WHO and from WHOM. In a later study, McCain (2018a) used White’s CAMEO frameworkFootnote 21 to examine patterns of acknowledgments made (ACK-Identity) and acknowledgments received (ACK-Image Makers) in profiling three researchers central to different coauthor networks. This approach identified the recipients of acknowledgments made (mostly to colleagues and coauthors) and acknowledgments received (mostly from outside the research group) but did not create single profiles for the three focal authors. The present study creates profiles for individual researchers and considers (but does not report) the authors of papers that acknowledge them.

Can we give a name to acknowledgees based on the kinds of acknowledgments they receive or postulate a role they might play in their research community? Cronin’s earliest acknowledgment studies included categories suggesting a particular kind of interpersonal connection between the acknowledger and acknowledgee (Prime Mover, Trusted Assessor) as well as others that focused more directly on the nature of what was being acknowledged (e.g., Paymaster). But these were quickly dropped in favor of terms that documented what was “provided” (funding support, technical assistance, PIC, etc.) and this has been the general form of the multi-part, single level acknowledgments classification since then.

What we can see in the profiles in Tables 11, 12, 13, and 14 are three different acknowledgment arrays. Nelson primarily gives advice on MS content and improving the English prose—to authors both within and outside her collaboration network. We might term her an “informal academic editorial consultant” based on the frequency of 3b Comments on manuscript and 5c English editing in her profile. Bertolani appears to be a “taxonomic gatekeeper”—he is one of the tardigrade researchers to contact when one needs access to key specimens (1g Reference materials & 1c Equipment & Facilities (collection) and relevant information (3a Specific information or suggestion).Footnote 223b Comments on manuscript occurs in only 1 time period and is primarily directed to members of his laboratory. Kristensen and Kaczmarek are “all-rounders’ (as we might expect many other author/acknowledgees to be); they are thanked for a wider range of different “gifts” (1g, 3a, 3b plus 4e Collecting organisms in the case of Kristensen).

Assessment

This research used a 4-time-period collaboration and personal acknowledgments analysis to explore the tardigrade literature over the years 1980–2023 (June). It sought ways to connect WHAT (acknowledgments made in the literature) with WHO (the recipient of the acknowledgments) and from WHOM (the article authors) at a level of detail not reported in previous acknowledgment studies. Coauthor mapping and annual publication patterns showed the growth of the field beginning in the early 2000s and the continuing importance of taxonomic and field studies seen in the earlier decades—content not seen in earlier model organism studies. The two-stage Personal Acknowledgments Classification used in the model organism studies was modified, adding one new category (1g Reference materials) and two category modifications (1c Equipment & facilities (collection) and 3d Special thanks (etymology) to accommodate this content.

The detail offered in the Personal Acknowledgments Classification, coupled with information on coauthor connections, was used to create profiles of four highly acknowledged tardigradologists and identify three different roles that researchers in this field may play, as evidenced by their acknowledgment patterns (which went beyond the PIC class). One additional contribution is the identification of an additional text location of acknowledgments data beyond the expected locations—another potential issue when relying on Web of Science and Scopus to capture personal acknowledgments along with the funding statements.

It’s unlikely that this approach to studying personal acknowledgments in the life sciences will be applicable when the goal is categorizing acknowledgments in the aggregate by mining large bodies of text using computer-assisted extraction and analysis. And it lacks the citation data that would interconnect all three “angles” of Cronin’s “reward triangle” (that remains for another day). It does demonstrate what one CAN learn with a closer, more detail-rich examination of personal acknowledgments data in a coherent research literature, connecting WHO, WHAT, and from WHOM while taking account of WHERE.

Future research

Possible future research can be looked at from two perspectives. First: follow-up studies might be conducted to explore more of the interpersonal relationships behind coauthorship and collaboration in general, with the tardigrade study as a point of departure. For instance, one could survey symposium attendees to see if interactions at the meetings led to collaborative research, access to research technology, or sharing of useful research information. One could also survey researchers to explore their attitudes and experiences giving and receiving acknowledgments. Second: my own research plans move beyond the world of tardigrade research to other examples of interesting research topics that are potentially even more diverse in terms of collaboration, coauthorship, and acknowledgment patterns. The two currently underway are a study of the literature dealing with cryoconite holes (depressions in the surface of glaciers that provide unique habitats for living organisms) and the literature looking at research on Solonopsis invicta, the Red Imported Fire Ant, which has invaded the southern/southwestern US, established outposts in other parts of the US, and is increasingly a problem in many other parts of the world. Both are likely to be highly multidisciplinary and yield interesting results.

Notes

I thank Dr. Desrochers for sharing the list of classified articles which was no longer available at the website mentioned in the paper.

Dr. Roger A. McCain, School of Economics, Drexel University, personal communication.

Ralph O.Schill, personal communication.

Additional archival coverage—1773–2000—was added to the Newsletter too late to be included in this study.

The partitioning was partly deliberate and partly unexpected but useful. The original data collection stopped in 2017—the more productive years (2000–2017) were split in half with the previous 20 years kept as a single file. Before any real analyses were run, the great Pandemic Shutdown happened, and all research pretty much stopped. ISSI 2023 gave me the opportunity to present preliminary results for 2009–2017; I used the opportunity to submit this paper as a reason to add 5.5 additional years of data and a fourth analytical period.

A complete comparison of the zebrafish (2000–2004) and tardigrade (1980–2023) ranked acknowledgments can be found in Appendix 2, with the differences in top rankings highlighted.

The most frequent country affiliation was determined by examining the author’s publications, personal or institutional website, and contact listing in the Tardigrade Newsletter.

The coauthor category “Laboratory members” in Tables 11, 12, 13, and 14 includes those coauthors who are physically associated with the selected tardigrade researcher, conducting research in an academic or other setting. A positive count shows the number of shared bylines. This may be too low to allow that lab member/coauthor to appear in one of the coauthor maps and not all the authors linked to the selected researcher in the map are members of his or her laboratory. This is a more focused and specific use of the term “laboratory” that the more general allusion to an “indoor” as opposed to a field setting (see discussion).

. Taxonomy involves the description, naming, and classification of organisms. Systematics looks at their diversity, interrelationships, and change over time. These two terms are generally linked together.

New species of tardigrades are described in detail and documented in a formal written description, along with drawings or microphotographs. Researchers are also encouraged to submit a DNA profile. A single specimen, designated the Holotype, will be fixed on a slide and deposited in a recognized repository. Specimens of the same unknown species collected at the same time and place (Paratype) are kept and preserved as well. The researcher will give the new species a name, most commonly based on location, ecological habitat, appearance, or to honor someone. Museums and other repositories will keep these slides in collections. See AMNH (2015) and Ohl (2018).

A similar increase in number and geographic diversity can be seen in the Tardigrada Newsletter symposium archives. Attendance between 1994 and 2018 ranged between a low of 35 (1997) and a high of 127 (2018), with a steady rise beginning with the 2006 symposium.

See Appendix 3 for a direct comparison of the top categories across all four time periods.

Tardigrades can live for decades in dried lichens and similar materials in which they were collected–stored in labeled envelopes and then reanimated by adding water. Presumably Pilato was studying material that was sent to him when Maucci was alive.

The range is from 225 papers with 1 author (225 papers) to a single 2016 paper in Nature with 28 authors from several Japanese labs.

It can happen that computer processing of automatically extracted acknowledgments will include a statement such as XXX is grateful to YYY agency for supporting this research where XXX is also the paper’s author.

Kusumegi & Sano (2022) considered similar collaborative relationships in their study of acknowledgments in open access journals but with a different goal in mind.

For example, “I would like to thank …; Professors Roberto Bertolani (Modena, Italy), Walter Maucci (Verona, Italy), Giovanni Pilato and Maria Grazia Binda (Catania, Italy) for the slides of some species and valuable information.

Diane R. Nelson, personal communication.

According to Petrovich (2022), the acknowledgments in analytic philosophy “usually mention the funding agencies that provided financial support to the research, the congresses where previous versions of the article were discussed, and, most importantly, the peers and other persons that contributed in various ways to the publications.” (p. 4/40). He did consider variables relating to individual acknowledgees but did not create individual profiles.

CAMEO—Characterizations Automatically Made and Edited Online. White’s framework focused on citations made and received in different profiles for individual authors (Identity—ranked list of people cited in the author’s papers; Citation Image—ranked list of authors co-cited with the focal author; Citation image-makers—ranked list of authors who cite the focal author in their papers. See White (2001).

Other tardigradologists not profiled here are similarly thanked for specimens and collection access.

References

Agnarsson, I., & Kuntner, M. (2007). Taxonomy in a changing world: Seeking solutions for a science in crisis. Systematic Biology, 56(3), 531–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150701424546

AMNH (American Museum of Natural History). (2015). Just our type: A short guide to type specimens. Retrieved 29 Oct 2023, from https://www.amnh.org/explore/news-blogs/from-the-collections-posts/just-our-types-a-short-guide-to-type-specimens.

Ankeny, R. A., & Leonelli, S. (2011). What’s so special about model organisms? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part A, 42(2), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2010.11.039

Baccini, A., & Petrovich, E. (2022). Normative versus strategic accounts of acknowledgment data: the case of the top-five journals of economics. Scientometrics, 127, 603–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-04185-6

Britz, R., Hundsdörfer, A., & Fritz, W. (2020). Funding, training, permits—The three big challenges of taxonomy. Megataxa, 1(1), 049–052. https://doi.org/10.11646/megataxa.1.1.10

Costas, R., & van Leeuwen, T. N. (2012). Approaching the “Reward Triangle”: General analysis of the presence of funding acknowledgments and “Peer Interactive Communication” in scientific publications. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(8), 1647–1661.

Cronin, B. (1995). The scholar’s courtesy: The role of acknowledgement in the primary communication process. Taylor Graham.

Cronin, B. (2001). Acknowledgment trends in the research literature of information science. Journal of Documentation, 57(3), 427–433.

Cronin, B., & Franks, S. (2006). Trading cultures: Resource mobilization and service rendering in the life sciences as revealed in the journal article’s paratext. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(14), 1909–1918. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20407

Cronin, B., Shaw, D., & La Barre, K. (2003). A cast of thousands: Coauthorship and subauthorship collaboration in the 20th century as manifested in the scholarly journal literature of psychology and philosophy. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(9), 855–871.

Cronin, B., Shaw, D., & La Barre, K. (2004). Visible, less visible, and invisible work: Patterns of collaboration in 20th century chemistry. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(2), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10353

Cronin, B., & Weaver, S. (1995). The praxis of acknowledgement: From bibliometrics to influmetrics. Revista Española De Documentación Científica, 18(2), 172–177.

Desrochers, N. & Pecoskie, J. (2014). Inner circles and outer reaches: Local and global information-seeking habits of authors in paratext research. Information Research, 19(1), paper 608. Retrieved from https://informationr.net/ir/19-1/paper608.html.

Desrochers, N., Paul-Hus, A., & Larivière, V. (2016). The Angle Sum Theory: Exploring the literature on acknowledgments in Scholarly Communication. In C. R. Sugimoto (Ed.) Theories of informetrics and scholarly communication. De Guyter, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110308464-014

Desrochers, N., Paul-Hus, A., & Pecoskie, J. (2017). Five decades of gratitude: A meta-synthesis of acknowledgments research. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 68(12), 2821–2833. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23903

Diaz-Faes, A. A., & Bordons, M. (2017). Making visible the invisible through the analysis of acknowledgments in the humanities. ASLIB Journal of Information Management, 69(5), 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-01-2017-0008

Ebach, M. C., Valdecasas, A. G., & Wheeler, Q. D. (2011). Impediments to taxonomy and users of taxonomy: Accessibility and impact evaluation. Cladistics, 27, 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-0031.2011.00348.x

Fahmy, C., & Young, J. T. N. (2015). Invisible colleagues: The informal organization of knowledge production in criminology and criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 26(4), 423–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2015.1051999

Guščytė, G., & Šinkūnienė, J. (2019). Research article acknowledgments across disciplines: Patterns of scholarly communication and tradition. ESP Today, 7(2), 182–206. https://doi.org/10.18485/esptoday.2019.7.2.4

Heo, G. E., Ko, Y. S., Xie, Q., & Song, M. (2023). High acknowledgment index: Characterizing research supporters with factors of acknowledgment affecting paper citation counts. Journal of Informetrics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2023.ac.kr

Hyland, K. (2003). Dissertation acknowledgments: The anatomy of a Cinderella genre. Written Communication, 20(2), 242–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088303257276

Hyland, K. (2004). Graduates’ gratitude: the generic structure of dissertation acknowledgements. English for Specific Purposes, 23(3), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(03)00051-6

Jia, P., Xie, W., Zhang, G., & Wang, X. (2023). Do reviewers get their deserved acknowledgments from the authors of manuscripts? Scientometrics, 128(10), 5687–5703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023004790-7

Kantha, S. S. (2017) Acknowledgments in Francis Crick’s papers appearing in science journals. Current Science, 112(8), 1768–1771. Retrieved from https://www.currentscience.ac.in/Volumes/112/08/1768.pdf.

Kusumegi, K., & Sano, Y. (2022). Dataset of identified scholars mentioned in acknowledgment statements. Scientific Data. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01585-y

Lou, W., He, J., Zhang, L., Zhu, Z., & Zhu, Y. (2023). Support behind the scenes: the relationship between acknowledgment, coauthor, and citation in Nobel articles. Scientometrics, 128(10), 5767–5790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04803-5

McCain, K. W. (2013). Charting the rise of the zebrafish as a model organism: Persistent co-author networks, 1980–2004 Presented at METRICS 2013: Workshop on Informetric and Scientometric Research, Montreal, Canada, 2 November 2013. 76th Annual Meeting of the Association for Information Science & Technology Montreal, Canada, 1–5 Nov 2013.

McCain, K. W. (2015). Collaboration patterns in model organism research: Co-authorship, acknowledgment, and the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis. Presented at METRICS 2015: Workshop on Informetric and Scientometric Research, St. Louis, MO, 7 Nov 2015. 78th Annual Meeting of the Association for Information Science & Technology, St. Louis, MO. 6–10 Oct 2015.

McCain, K. W. (2017) Undercounting the gift givers: issues when tallying acknowledgements in life sciences research. Presented at METRICS 2017: Workshop on Informetric and Scientometric Research, Crystal City, VA, 27 Oct 2017. 80th Annual Meeting of the Association for Information Science & Technology, Crystal City, VA 27 Oct–1 Nov 2017.

McCain, K. W. (1991). Communication, competition, and secrecy: The production and dissemination of research-related information in genetics. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 16(4), 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/016224399101600404