Abstract

This paper examines the importance of spatial proximity in research collaborations, focusing on China’s transportation infrastructure advancements. Analyzing academic papers published by Chinese institutions over three decades, we find that collaboration probability is positively correlated with institutions’ research output and negatively correlated with geographic distance. When considering other dimensions of proximity, administrative proximity and social network proximity exhibit the most substantial influence. Employing staggered difference-in-differences methods, we then establish causal inferences by investigating the effects of direct flight routes and high-speed rail (HSR) connections. Findings show that both modes of transportation contribute to enhanced academic collaborations. Specifically, the introduction of flight routes leads to an increase in collaborations of at least 10.66%, while the establishment of HSR connections results in an increase by at least 32.65%. Flight routes are advantageous for facilitating collaborations in medium to long distances, while HSR primarily benefits medium to short-distance collaborations. Efficient public transportation connections, by reducing travel time, can significantly enhance collaboration across broader spatial areas within the knowledge production sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to the “Statistical Analysis of Chinese Scientific Papers in 2020” released by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, in 2020, China published 553 thousand SCI papers, accounting for 23.7% of the global total. This proportion was only 3.2% in the year 2000.

The data was last updated at 2023-03-28.

Different schools or departments within a same university are treated as a single institution. It’s worth noting that we identified the primary affiliation of each author for every article based on the authorship information provided in the papers. We allow for the possibility that the same author could have different affiliations at different time.

The article’s DOI is: https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.191803. It's challenging to determine whether there is research collaboration between all these authors. Including such articles in the analysis would introduce more noise than useful information, potentially interfering with the measurement of inter-institutional collaboration to some extent.

The number of institutions is not more than the number of authors in a paper, e.g., 4 authors in 2 institutions.

Cities in this article refers to (a) prefecture-level regions, and (b) county-level regions under direct provincial control.

We have provided the information regarding city pairs with collaborations over the years in the appendix.

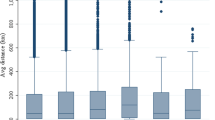

The term “distance” mentioned in this paper, including the subsequent variable dist, refers to spherical distances calculated using the latitude and longitude of institutions.

It’s calculated from 337 prefecture-level administrative regions, including 293 prefecture-level cities, 7 regions, 30 autonomous prefectures, 3 leagues, and 4 municipalities.

For instance, Marek et al. (2017) measured cognitive proximity based on the similarity of regional industry structures, while Bergé (2017) used the similarity of research portfolios, essentially representing technological proximity. These measures do not necessarily capture true cognitive proximity in its purest sense.

We determine whether two cities are in the same dialect region based on the information recorded in the Chinese Dialect Dictionary. In cases where a region has multiple dialects, we select the dialect with the highest coverage as the representative one.

We define institutional pairs that have collaborated more than 5 times as having long-term collaborators.

In a total of 8,796,915 bilateral pairs formed by 4195 institutions, academic collaboration occurred in only 4.04%.

It’s essential to emphasize that the aggregation at the city-pair level is not a simple summation of institution-pair level data. This is because situations can arise where an article is collaboratively authored by two institutions \({i}_{1}\) and \({i}_{2}\) situated in city \({c}_{1}\), collaborating with a single institution j located in city \({c}_{2}\). Consequently, a direct aggregation could lead to duplications, wherein collaborations (\({i}_{1}\), j) and (\({i}_{2}\), j) would be redundantly counted as collaboration between cities \({c}_{1}\) and \({c}_{2}\).

Other dimensions of proximity either become inapplicable due to aggregation (e.g., organizational and social network proximity) or have negligible impact (e.g., the variable SameDialect used to measure cultural proximity).

In the Logit model, we present ORs rather than MEs mainly because MEs estimated by the Logit and Probit models are nearly identical. ORs can offer added insights as they emphasize the proportional alteration in collaboration odds resulting from a one-unit shift in the independent variable. In contrast, MEs predominantly center on the actual alterations in probability of collaboration.

Results not reported due to space constraints.

In the appendix, we provide estimations from the linear probability model (LPM), which incorporates institutional FE. This method significantly mitigates concerns associated with omitted variables.

We have also provided in the appendix the tests plotted using 95% confidence intervals. The conclusion remains valid.

If a city did not have an airport during the sample period, all city pairs associated with that city will be excluded. The same procedure applies to subsequent analyses.

We have provided a detailed explanation in the appendix, discussing spatial distribution and its impact.

The Poisson regressions and negative binomial regressions are estimated using the xtpoisson and xtnbreg commands in Stata software, respectively.

It’s worth noting that at this point, the relative magnitudes of the effects of flights and HSR remain inconclusive, possibly due to the influence of the distribution of the dependent variable on these count models.

The fundamental principle of this method is to match each observation in the treatment group with observations that either never received treatment or have not yet received treatment, creating a comprehensive dataset. Subsequently, these datasets are stacked together, and a linear regression analysis is performed, incorporating group-by-individual and group-by-time FE. The stacked event study estimations are implemented conducted using the “stackedev” command in Stata.

References

Acosta, M., Coronado, D., Ferrándiz, E., & León, M. D. (2011). Factors affecting inter-regional academic scientific collaboration within Europe: The role of economic distance. Scientometrics, 87(1), 63–74.

Agrawal, A., & Goldfarb, A. (2008). Restructuring research: Communication costs and the democratization of university innovation. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1578–1590.

Anderson, J. E., & Van Wincoop, E. (2003). Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. American Economic Review, 93(1), 170–192.

Asheim, B. T., & Gertler, M. S. (2006). The geography of innovation: regional innovation systems. The Oxford Handbook of Innovation. Oxford University Press.

Bai, J. J., Jin, W., & Zhou, S. (2021). Proximity and knowledge spillovers: Evidence from the introduction of new airline routes. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3851753

Baker, A. C., Larcker, D. F., & Wang, C. C. (2022). How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? Journal of Financial Economics, 144(2), 370–395.

Bergé, L. R. (2017). Network proximity in the geography of research collaboration. Papers in Regional Science, 96(4), 785–815.

Boschma, R. A. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74.

Cairncross, F. (1997). The death of distance: How the communications revolution is changing our lives. Harvard Business Press.

Campos, R., Leon, F., & McQuillin, B. (2018). Lost in the storm: The academic collaborations that went missing in hurricane ISSAC. The Economic Journal, 128(610), 995–1018.

Cassi, L., & Plunket, A. (2015). Research collaboration in co-inventor networks: Combining closure, bridging and proximities. Regional Studies, 49(6), 936–954.

Cengiz, D., Dube, A., Lindner, A., & Zipperer, B. (2019). The effect of minimum wages on low-wage jobs. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3), 1405–1454.

Cerdeira, J., Mesquita, J., & Vieira, E. S. (2023). International research collaboration: Is Africa different? A cross-country panel data analysis. Scientometrics, 128(4), 2145–2174.

Chen, Z., Lu, M., & Xu, L. (2014). Returns to dialect: Identity exposure through language in the Chinese labor market. China Economic Review, 30, 27–43.

Crescenzi, R., Nathan, M., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2016). Do inventors talk to strangers? On proximity and collaborative knowledge creation. Research Policy, 45(1), 177–194.

Cui, J., Li, T., & Wang, Z. (2023). Research collaboration beyond the boundary: Evidence from university patents in China. Journal of Regional Science, 63(3), 674–702.

Cunningham, S. W., & Werker, C. (2012). Proximity and collaboration in European nanotechnology. Papers in Regional Science, 91(4), 723–742.

D’ippolito, B., & Rüling, C. C. (2019). Research collaboration in large scale research infrastructures: Collaboration types and policy implications. Research Policy, 48(5), 1282–1296.

Dahlander, L., & McFarland, D. A. (2013). Ties that last: Tie formation and persistence in research collaborations over time. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(1), 69–110.

De Chaisemartin, C., & d’Haultfoeuille, X. (2020). Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. American Economic Review, 110(9), 2964–2996.

D’Este, P., Guy, F., & Iammarino, S. (2013). Shaping the formation of university–industry research collaborations: What type of proximity does really matter? Journal of Economic Geography, 13(4), 537–558.

Engel, C., & Rogers, J. H. (1996). How wide is the border? The American Economic Review, 1996, 1112–1125.

Falck, O., Heblich, S., Lameli, A., & Südekum, J. (2012). Dialects, cultural identity, and economic exchange. Journal of Urban Economics, 72(2–3), 225–239.

Feldman, M. P., & Kogler, D. F. (2010). Stylized facts in the geography of innovation. Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, 1, 381–410.

Freeman, R. B., & Huang, W. (2015). Collaborating with people like me: Ethnic coauthorship within the United States. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(S1), S289–S318.

Giroud, X. (2013). Proximity and investment: Evidence from plant-level data. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2), 861–915.

Hammond, M. (2017). Online collaboration and cooperation: The recurring importance of evidence, rationale and viability. Education and Information Technologies, 22, 1005–1024.

Hansen, T. (2014). Juggling with proximity and distance: Collaborative innovation projects in the Danish Cleantech industry. Economic Geography, 90(4), 375–402.

Hoekman, J., Frenken, K., & Tijssen, R. J. (2010). Research collaboration at a distance: Changing spatial patterns of scientific collaboration within Europe. Research Policy, 39(5), 662–673.

Irving, G. L., Ayoko, O. B., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2020). Collaboration, physical proximity and serendipitous encounters: Avoiding collaboration in a collaborative building. Organization Studies, 41(8), 1123–1146.

Kabo, F. W., Cotton-Nessler, N., Hwang, Y., Levenstein, M. C., & Owen-Smith, J. (2014). Proximity effects on the dynamics and outcomes of scientific collaborations. Research Policy, 43(9), 1469–1485.

Kafouros, M., Wang, C., Piperopoulos, P., & Zhang, M. (2015). Academic collaborations and firm innovation performance in China: The role of region-specific institutions. Research Policy, 44(3), 803–817.

Katz, J. (1994). Geographical proximity and scientific collaboration. Scientometrics, 31(1), 31–43.

Knoben, J., & Oerlemans, L. A. (2006). Proximity and inter-organizational collaboration: A literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8(2), 71–89.

Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing returns and economic geography. Journal of Political Economy, 99(3), 483–499.

Liang, L., & Zhu, L. (2002). Major factors affecting China’s inter-regional research collaboration: Regional scientific productivity and geographical proximity. Scientometrics, 55(2), 287–316.

Marek, P., Titze, M., Fuhrmeister, C., & Blum, U. (2017). R&D collaborations and the role of proximity. Regional Studies, 51(12), 1761–1773.

Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of economics. Macmillan and Company.

McCallum, J. (1995). National borders matter: Canada-US regional trade patterns. American Economic Review, 85(3), 615–623.

Melin, G., & Persson, O. (1996). Studying research collaboration using co-authorships. Scientometrics, 36(3), 363–377.

Newman, M. E. (2001). The structure of scientific collaboration networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 404–409.

Newman, M. E. (2004). Coauthorship networks and patterns of scientific collaboration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(1), 5200–5205.

Ponds, R., Van Oort, F., & Frenken, K. (2007). The geographical and institutional proximity of research collaboration. Papers in Regional Science, 86(3), 423–443.

Salazar Miranda, A., & Claudel, M. (2021). Spatial proximity matters: A study on collaboration. PLoS ONE, 16(12), e0259965.

Van Rijnsoever, F. J., & Hessels, L. K. (2011). Factors associated with disciplinary and interdisciplinary research collaboration. Research Policy, 40(3), 463–472.

Vieira, E. S., Cerdeira, J., & Teixeira, A. A. (2022). Which distance dimensions matter in international research collaboration? A cross-country analysis by scientific domain. Journal of Informetrics, 16(2), 101259.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press.

Yao, L., & Li, J. (2022). Intercity innovation collaboration and the role of high-speed rail connections: evidence from Chinese co-patent data. Regional Studies, 56(11), 1845–1857.

Young, A. (2000). The razor’s edge: distortions and incremental reform in the People’s Republic of China. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4), 1091–1135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, X., Huang, T. Proximity still matters in research collaboration! Evidence from the introduction of new airline routes and high-speed railways in China. Scientometrics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04910-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04910-3