Abstract

We aimed to examine the differences in articles, peer review and editorial processes in Medical and Health Sciences vs. Social Sciences. Our data source was Open Research Central (ORC) portal, which hosts several journal platforms for post-publication peer review, allowing the analysis of articles from their submission, regardless of the publishing outcome. The study sample included 51 research articles that had Social Sciences tag only and 361 research articles with Medical and Health Sciences tag only. Levenshtein distance analysis showed that text changes over article versions in social science papers were statistically significant in the Introduction section. Articles from Social Sciences had longer Introduction and Conclusion sections and higher percentage of articles with merged Discussion and Conclusion sections. Articles from Medical and Health Sciences followed the Introduction-Methods-Results-Discussion (IMRaD) structure more frequently and contained fewer declarations and non IMRaD sections, but more figures. Social Sciences articles had higher Word Count, higher Clout, and less positive Tone. Linguistic analysis revealed a more positive Tone for peer review reports for articles in Social Sciences and higher Achievement and Research variables. Peer review reports were significantly longer for articles in Social Sciences but the two disciplines did not differ in the characteristics of the peer review process at all stages between the submitted and published version. This may be due to the fact that they were published on the same publication platform, which uses uniform policies and procedures for both types of articles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research disciplines differ not only in the topic and focus of their research but also in the structure of the manuscripts, peer review evaluation, editorial processes, and research methodology. Because research work is more closely linked to reading and writing in some areas, such as humanities, the differences may occur in the language and writing styles and in the preferred ways of communicating research findings, whether it is in the form of an article or a monograph. Bellow we present literature review on the differences in manuscripts and peer-review processes across different research areas.

Manuscript differences

A study of linguistic differences between research areas in 500 abstracts of research articles published in 50 high-impact journals, showed that each of the five areas—earth, formal (i.e. related to formal systems such as logic, mathematics, statistics), life, physical and social science—have their own set of “macro-structural, metadiscoursal and formulation features” (Ngai et al., 2018). For example, medical and health sciences have been using the IMRaD article format (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion) since the 1950s (Sollaci et al., 2004), whereas research disciplines such as social sciences tend to have a more flexible article structure. Predominant publication outputs in social sciences (and also humanities) are academic monographs and books (Williams et al., 2009; Wolfe, 1990). Also, articles in social sciences journals tend to be longer than those in medical journals (Silverberg & Ray, 2018). Another difference is that the natural sciences research strategies are more adapted to “large concentrated knowledge clusters”, whereas social sciences usually adapt their research strategies to “many small isolated knowledge clusters” (Jaffe, 2014).

Peer review differences

The importance of the evaluation process for researchers and research in general has been the topic of numerous studies, from examining the impact of peer review on submitted manuscripts to some specific characteristics of peer review reports. Recently, initiatives to share peer review data on peer review (Squazzoni et al., 2020), have brought about better understanding of the peer review process across different disciplines (Buljan et al., 2020; Squazzoni et al., 2021a, 2021b), particularly in the type of peer review. In open peer review, authors and reviewers know each other’s identity and sometimes reviewer reports are published next to the articles (Ross-Hellauer, 2017), whereas in post-publication peer review, articles are reviewed after publication in an open review process (Ford, 2015). In medical and health Sciences, open and post-publication peer review are becoming more common and peer review reports are often published together with the articles (Hamilton et al., 2020). In social sciences, the peer review process has remained closed because double blind peer review is still preferred (Karhulahti & Backe, 2021). In recent years, however, some platforms publishing articles from social sciences and humanities, such as Palgrave Macmillan, have adopted the practice of open peer review (Palgrave MacMillan, 2014). This allows researchers to study the peer review process in social sciences and humanities and to compare it with other research areas.

A study exploring the role of peer review in increasing the quality and value of manuscripts (Garcia-Costa et al., 2022) showed that the impact of peer review is shared across research areas but not without certain differences, as reports from social sciences and economic journals displayed the highest “developmental standards”.

Regarding the linguistic differences, a study of almost half a million peer review reports from 61 journals (Buljan et al., 2020) showed that peer review reports were longer in social sciences than in medical journals, but there were no differences in the length between double- and single-blind reviews. Language characteristics were also different across disciplines (Buljan et al., 2020): peer review reports in medical journals had low Authenticity (impersonal and cautious language) and high analytical Tone (use of more formal and logical language), whereas the language of peer review reports in social sciences journals had high Authenticity (personal and open language) and high Clout (honest and humble reporting and high level of confidence). Using natural language techniques, Rashidi et al. (2020), studied published articles and their open peer review reports from F1000Research journal, which uses a post-publication peer review. They found consistency and similarity in the use of salient words, like those from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) of MEDLINE. F1000Research platform was also used to develop a sentiment analysis program to detect praise and criticism in peer evaluations (Thelwall et al., 2020), which showed that negative evaluations in reviewer’s comments better predict review outcomes than positive comments.

Peer review research carries major challenges due to the lack of access to the whole process of scientific publication. This means that peer review process remains hidden from the submission of the article to its rejection or publication after peer review, hindering our understanding of the publishing process. For this reason, we decided to use the Open Research Central (ORC) portal, which hosts several journal platforms for post-publication peer review (Tracz, 2017) to study the characteristics of articles and peer review reports in Medical and Health Sciences and Social Sciences. Journals at the ORC platform are multidisciplinary and use the post-publication review: the articles are publicly available upon submission, and access is possible to the whole peer review and editorial decision-making process (ORC, 2022). To our knowledge, there has not been a study that analysed the peer review reports from this platform. The aim of our study was to examine possible differences in the submitted articles and peer review process in Medical and Health Sciences vs. Social Sciences. We examined: (i) the structural and linguistic differences between research articles; (ii) the characteristics of the peer review process; (iii) the language of peer review reports; and (iv) the outcomes of peer review process.

Methods

Data source: ORC portal

ORC currently includes the following journals: F1000Research, Wellcome Open Research, Gates Open Research, MNI Open Research, HRB Open Research, AAS Open Research, AMRC Open Research and Emerald Open Research.

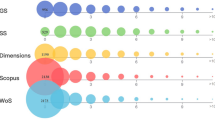

Identify the articles: get articles’ DOIs

Using the ORC search engine (https://openresearchcentral.org/browse/articles) and Python 3.8.5 (https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-385/), we performed 2 automatic queries applying the following filters: “Article type(s): Research Article” and “Subject area: Medical and Health Sciences”, or “Subject area: Social Science”. We then extracted the articles’ DOIs using requests (https://docs.python-requests.org/en/latest/) and Beautiful Soup (https://beautiful-soup-4.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) HTTP libraries for Python. We retrieved 1912 Medical and Health and 477 Social Sciences articles. In order to create the samples of articles with clear Medical and Health vs. Social Sciences content, we excluded articles with a tag for both disciplinary fields, those with a tag for Medicine and Health Sciences and any other disciplinary field except Biology and Life Science, and those with a tag both for Social Sciences and Biology and Life Sciences. This was done also to ensure that manuscripts and peer review reports were not influenced by the language and writing style of multiple research areas. This left with 408 Medical and Health and 54 Social Science articles (Fig. 1).

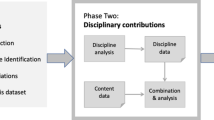

A flowchart representing methods workflow (created using Zen Flowchart: https://www.zenflowchart.com/)

Retrieve the articles in XML format

Using the DOIs of filtered articles, we downloaded the articles manually in an XML format. We used the XML article format in order to achieve better quality data mining due to its semantic and machine-readable tagging. All versions of articles were downloaded in order to get complete article information.

XML Parser: extract and save relevant data

We used the ElementTree library in Python (xml.etree.ElementTree — The ElementTree XML API — Python 3.10.1 documentation) for parsing data from the XML files. First, the articles that had not been reviewed were excluded, yielding a total of 51 articles with a Social Sciences tag and 361 articles with a Medical and Health Sciences tag. A simplified sequence diagram for XML document parser is shown in Fig. 2.

A simplified sequence diagram for ORC XML parser (the diagram was created using PlantUML open-source tool https://plantuml.com/sequence-diagram)

Using the scripts, we extracted the following variables:

-

(1)

Length of an article and the length of the individual article chapter – Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion (IMRaD);

-

(2)

Number of figures, tables and supplementary material in the articles;

-

(3)

Percent of articles following the IMRaD structure;

-

(4)

Linguistic characteristics of the articles such as Tone, Sentiment, etc.;

-

(5)

Male to female ratio among article reviewers;

-

(6)

Time for an article to be first posted;

-

(7)

Number of rounds of review until the article is accepted;

-

(8)

Time to review each version of the article;

-

(9)

Time for an article to have a “positive” status;

-

(10)

Length of review comments;

-

(11)

Linguistic characteristics of research articles and corresponding peer reviews; and

-

(12)

Reviewers’ recommendations.

Reviewers’ gender was determined by using Python class Genderize from Genderize.io web service (https://pypi.org/project/Genderize/), which predicts the gender of a person given their name.

Details on how each of the variables was extracted from the XML files can be found in the following Python scripts: https://github.com/Tonija/ORC_scripts.

The results of the scripts were saved in a csv table and used for linguistic and statistical analysis.

Linguistic analysis

Linguistic inquiry word count (LIWC)

The texts of the articles and corresponding peer reviews were analysed using the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count (LIWC) text analysis software program (Pennebaker et al., 2015a). We calculated LIWC’s five default variables (Word count, Analytic, Clout, Authentic, Tone), where Word count (WC) is the raw number of words in a given text, while Analytic, Clout, Authentic, and Tone are the linguistic variables expressed as percentages of total words within a text (Pennebaker et al., 2015b). Higher scores on the Analytic dimension describe the use of formal, logical, and hierarchical language; higher Clout score refers to a higher level of leadership and confidence; higher Authentic score points to a more personal way of writing; and higher Tone score represents a more positive emotion dimensions (Pennebaker et al., 2015b).

We also analysed seven other LIWC categories related to research evaluation, used for linguistic study of letters of recommendation for academic job applicants (Schmader et al., 2007), and for text analysis of research grant reviewers’ critiques (Kaatz et al., 2015). These words categories with examples are: Ability (brillian*, capab*, expert*, proficien*); Achievement (accomplish*, award*, power*, succeed*); Agentic (ambiti*, assert*, confident*, decisive*); Research (data, experiment*, manuscript*, research*); Standout adjectives (extraordinar*, remarkable, superb*, unique); Positive evaluation (appropriat*, clear*, innovat*, quality); and Negative evaluation (bias*, concern*, fail*, inaccura*). Higher Ability refers to higher usage of adjectives that describe talent, skill, or proficiency in a particular area; higher Achievement score refers to higher usage of terms that relate to success and achievement; higher Agentic score points to higher usage of words that describe achieving goals; higher Research score indicates higher usage of research terminology; higher Standout adjectives score reflects the use of adjectives describing exceptional, noticeable skill or performance; and higher Positive (Negative) evaluation score indicates higher (lower) display of affirmation and acceptance.

Word embeddings and t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding

We also explored whether the texts of the articles and peer review reports from the two research disciplines formed different word clusters.

For peer review reports, we applied Word Embeddings, a method in which words are given mathematical vector representation so that they are mapped to points in Euclidean space, with words that are similar in meaning being closer to each other (Hren et al., 2022; Jurafsky et al., 2000). We used the Gensim library and Word2Vec approach in Python to create Word Embeddings, as well as a pre-trained model (https://github.com/lintseju/word_embedding), trained on Wikimedia database dump of the English Wikipedia on February 20, 2019. Finally, clusters were visualised using TensorBoard Embedding Projector (https://projector.tensorflow.org/), which projects the high-dimensional data into three dimensions. The projector uses the principal components analysis (PCA) to visualise clusters and cosine distances between clusters as a reference to cluster distances. After the data points were created, we attached the labels by uploading a metadata file we previously generated with a Python script. We applied this technique only to peer review reports because the texts of the articles were a too large for TensorBoard Embedding Projector.

For article texts we applied t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) technique using the TSNE class from the Scikit-learn (Sklearn) Python library (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.manifold.TSNE.html), which visualises high-dimensional data by placing each datapoint in a two-dimensional map (van den Maaten & Hinton, 2008). We used the Global Vectors for Word Representation (GloVe) pre-trained model that was trained using Wikipedia 2014 + Gigaword 5 (Pennington et al., 2014).

Word frequency in peer review reports

We also examined whether there would be differences in peer review reports in Social versus Medical and Health Sciences regarding the most common words usage. We calculated the percentage of words found in the 10,000 most common English words in the Project Gutenberg list (Wiktionary, 2006), as well as in the Academic Word List (AWL), which contains 570 words that are specific to written academic texts but are not included in the 2000 English words from the General service List (Coxhead, 2000; Coxhead & Nation, 2001). Finally, we identified the most frequent words that were unique to peer review reports in Social Sciences (i.e. not found in peer review reports in Medical Sciences in our sample) and vice versa.

Changes in manuscript versions: Levenshtein distance

Because of a small number of strictly Social Sciences articles, for this analysis we included Social Sciences articles that overlaped with Biology and Life Science, yielding 48 social and 166 articles from Medical and Health Sciences.

We measured the changes in the text from the first draft to the second version of a manuscript by means of the Levenshtein distance (Levenshtein, 1966), a character-based metric counting the minimum number of edit operations (insertions, deletions or substitutions) required to transform one text into the other. We computed this distance on the overall textual content of the manuscript, including figure captions and tables, but skipping references.

Changes in the references were calculated as the ratio of references being edited (added or deleted) to the total number of distinct references in both the first and the last version of the manuscript. To give two examples, we measured a change as 0.5 when the references of a manuscript changed from [A, B, C] to [A, B, D] (i.e. 2 changes of 4 references) and we calculated a value of 0.25 for a change from [A, B, C, D] to [A, B, C] (i.e. 1 change of 4 references). Two references were considered as equal by a matching algorithm (Vincent-Lamarre & Larivière, 2021) that checked whether they had the same publication year, the same number of authors, and a Levenshtein distance lower than 0.1 between the list of authors and the paper titles.

Statistical analysis

To assess possible differences between the articles and their reviews across Medical and Health, and Social Sciences, one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test were employed. For multivariate frequency distribution of the variables, Contingency test was utilised. All analyses were carried out in JASP, Version 0.14.1. (JASP Team, 2020).

Results

Structural and linguistic differences of articles in Social Sciences vs. Medical and Health Sciences

Articles from Medical and Health Sciences and Social Sciences differed in their structure (Table 1). Both the Introduction and Conclusion sections were longer for Social Sciences than those from Medical and Health Sciences. The number of additional sections and the number of special sections was also higher for articles in Social Sciences. Discussion and Conclusion sections were merged more often in Social Sciences articles, whereas Medical and Health Sciences articles often had Conclusions as a separate section. Articles in Medical and Health Sciences followed the IMRaD structure more frequently, and contained more figures.

Linguistic analysis was performed on the text of the latest version of an article. Articles in Social Sciences had higher Word count and higher Clout, whereas the articles in Medical and Health Sciences had a higher Tone score.

Characteristics of the peer review process and peer review reports from all stages of review in Social Sciences vs. Medical and Health Sciences

No statistically significant differences were found in the characteristics of the peer review reports from all stages of review between articles from Social Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences: reviewer’s gender, time between the first and second manuscript version posted, time between acceptance for publication and the first article version, time between the first and finally approved article version, as well as the number of article versions (Table 2).

Comparison of linguistic characteristics of peer review reports in Social Sciences vs. Medical and Health Sciences

Peer review reports were significantly longer for articles in Social Sciences (Table 3). Social Sciences peer review reports also had higher scores on several linguistic characteristics: Clout, Authentic, Tone, Agentic, Achievement, Research and Standout (Table 3).

Linguistic differences between research articles and corresponding peer reviews in Social Sciences vs. Medical and Health Sciences

We also compared the linguistic characteristics of the articles and their corresponding peer review reports (Table 4). In general, the articles had higher scores for the Analytic, Clout and Authentic variables than corresponding peer review reports, whereas peer review reports had a significantly higher positive Tone compared to the language of the corresponding articles.

The difference between the linguistic characteristics of articles and peer review reports was significantly higher for the Clout score for Social Sciences than for Medical and Health Sciences articles (Table 4). The opposite was true for the Tone score, where the difference between the articles and peer review reports was greater for Medical and Health Sciences articles (Table 4).

Comparison of reviewers’ recommendations for articles in Social Sciences vs. Medical and Health Sciences

There were no statistically significant differences in the outcome of the peer review process between the two disciplines, measured as the number of reviewers’ recommendations for different versions of the articles (Table 5). For articles in both disciplines, about a half of the articles were approved already at the stage of the first version. The proportion of reject recommendations were low and decreased in the next versions, with only a single article (in Medical and Health Sciences) receiving a rejection recommendation at the level of the third article version (Table 5).

Changes in the text of the manuscript were mainly concentrated in the Methods and Results & Discussion sections (Table 6), as measured by the higher values of the Levenshtein distance metric. References also changed, predominantly by adding more references. The differences between the disciplines were statistically significant only for the Introduction section, which was the least modified section in the Medical and Health Sciences.

Changes to the latest version of articles in Social Sciences vs. Medical and Health Sciences

Word cluster visualisation

Using the Word Embedding visualisation of words, we observed that, the words in peer review reports from Social Sciences were more spherically distributed, which means that they had more general terms that could be found in other research areas, for example (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, clusters consisting of specific terms were found in Medical and Health Sciences peer reviews (Fig. 3B).

Word Embeddings 3D visualisation for reviews in Social Sciences (left) vs. Medical and Health Sciences (right). Clustering indicates grouping together the closest or most similar words; the closer two words are, the more similar they are, and vice versa. Gensim library and Word2Vec approach in Python were used to create Word Embeddings, as well as a pre-trained model (https://github.com/lintseju/word_embedding), trained on Wikimedia database dump of the English Wikipedia on February 20, 2019 and the clusters were visualised using TensorBoard Embedding Projector (https://projector.tensorflow.org/)

Using the t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) visualisation, we observed similar distributions for the words in text of the articles: words from Social Sciences were more spherically distributed as well, having more general terms (Fig. 4A) while clusters consisting of specific terms were found in Medical articles texts (Fig. 4B). GIF format of the images can be found in the Appendix.

The-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) visualisation (van den Maaten & Hinton, 2008) for texts of the articles in Social Sciences (A) vs. Medical and Health Sciences (B) in a two-dimensional map. Created using the TSNE class from the Scikit-learn (Sklearn) Python library (Skicit learn, 2022) and the Global Vectors for Word Representation (GloVe) pre-trained model that was trained using Wikipedia 2014 + Gigaword 5 (Pennington et al., 2014)

Peer review reports from Social Sciences contained a higher percentage of words from the Academic Word List (8.5%) compared to peer review reports from Medical and Health Sciences (7.2%) (MD = − 1.3, 95% CI − 1.7 to − 0.8). They also contained a higher percentage of the 10,000 most common English words (76.7%) compared to peer review reports from Medical and Health Sciences (72.7%) (MD = − 4.0, 95% CI − 5.0 to − 3.0).

Most common and most common unique words found in peer reviews can be found in Table 7.

Discussion

Understanding the differences between Medical and Health Sciences and Social Sciences in their structural and linguistic characteristics is crucial for successful interdisciplinary collaborations and for avoiding misunderstandings between different research groups. Our study found certain differences both in articles and peer review reports regarding to their structure and linguistic characteristics.

Structural differences in articles and peer review reports between Social and Medical and Health Sciences

Longer articles and peer review reports in Social Sciences compared to Medical and Health Sciences could reflect the tradition of the writing style and formats typically used in the disciplines. Despite an increase of journal articles as a publication output for social sciences and humanities (Savage & Olejniczak, 2022), academic monographs and books are still being used as forms of scholarly dissemination in the humanities and some social sciences, sometimes even remaining crucial for professional advancement (Williams et al., 2009). Some university departments emphasise publishing in the form of books and monographs (Wolfe, 1990). Typically, monographs range between 70,000 and 110,000 words, which makes them significantly longer than a standard or even the longest journal article. The length of journal articles also differs across disciplines, with medical journals usually strict limits for article word count. For example, in five medical journals (New England Journal of Medicine [NEJM], Lancet, JAMA, BMJ and Annals of Internal Medicine), the word limits for the main text ranges from 2700 (NEJM) to 4400 (BMJ) (Silverberg & Ray, 2018). On the other hand, social sciences journals allow longer papers and they typically limit the manuscript size in the number of pages. For example, in four social sciences journals (Review of Economics and Statistics [Rev Econ Stat], Journal of Business and Economic Statistics [JBES], Human relations, Journal of Marriage and Family [JMF]), page limits for the main text ranged from 35 (JBES and JMF) to 45 (Rev Econ Stat), the limit often being a recommendation rather than obligation. Some journals, such as Sociological Science, do not have any limits related to manuscript length. A 2011 market research conducted by Palgrave Macmillan, a publisher of books and journals in humanities and social sciences, in which they surveyed 1,268 authors and academics from humanities and social sciences, the majority of respondents expressed that the perfect length would be between a journal article and a monograph (McCall, 2015). This resulted in the development of Palgrave Pilot, a format ranging between 25,000 and 50,000 words (McCall, 2015).

Medical and Health Science articles were shorter, but contained more images and graphs compared to Social Sciences articles. However, studies suggest that even in medical sciences journals, graphs are underused (Chen et al., 2017), they are often not self-explanatory and fail to display full data (Cooper et al., 2001). Peer review seems to improve graph quality but there is further need for improvement (Schriger et al., 2016). Because social sciences are entering a golden age (Salganik, 2019), with more data available (Buyalskaya et al., 2021), social sciences authors should also recognize the importance of the visual data presentation and increase the number of graphs and figures.

As expected, Medical and Health Science articles more often followed the IMRaD format compared to Social Sciences, since they were among the first to adopt IMRaD structure. This is not surprising since research in health and life sciences most often uses a hypothetico-deductive approach (Jürgen, 1968; Lewis, 1988), which starts from a hypothesis, moves to observation and comes to a conclusion. IMRaD is the perfect format to present such research as it follows the structure of a logical argument (Puzzo & Conti, 2021). social sciences, on the other hand, widely use a mixed method approach (Plano Clark & Ivankova, 2016; Timans et al., 2019), which incorporates both deductive and inductive methods (Creswell, 2012). Inductive approach moves from observation to hypothesis, and the IMRaD format may not be suitable. As there is an increase in mixed method approach in health and clinical sciences (Plano Clark, 2010; Coyle et al., 2018), it is questionable whether IMRaD can and should be a one-size-fits-all format of journal article. If research is done inductively, should it be presented in IMRaD format? There are even arguments that the current publishing process discourages inductive research (Woiceshyn & Daellenbach, 2018). Nevertheless, as the format of research paper has evolved from descriptive to standardised style (Kronick, 1976), IMRaD format will continue to evolve as well (Wu, 2011) to adapt to the diversification of methodological approaches in different scientific disciplines and particularly in multi- and interdisciplinary work.

Linguistic differences in articles and peer review reports between Social Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences

Articles in Social Sciences had higher Word count, Clout, and Authenticity, whereas articles in Medical and Health Sciences had higher Analytic and Tone score. Higher Authenticity score for social sciences articles, which indicates a more personal way of writing, is not an unexpected finding as analyses in social sciences and humanities often relay on interpretations based on researcher’s personal opinions and values, leading to subjectivity (Khatwani & Panhwar, 2019). Higher Analytic score for articles in Medical and Health Sciences, which reflects the use of formal, logical, and hierarchical language, does not surprise due to the hypothetico-didactic methodological approach and “dispassionate scientific language” that is frequently used in these disciplines (Steffens, 2021). This is partially in accordance with previous studies that compared peer review reports in social sciences and medical and health sciences. Understanding the language differences between disciplines is important because linguistic characteristics of manuscripts may have an effect on the evaluation process. Peer review has a crucial role in determining the fate of manuscripts. If peer review reports contain more positive words and/or expressions, research manuscripts are more likely to be accepted for publishing (Fadi Al-Khasawneh, 2022; Ghosal et al., 2019; Wang & Wan, 2018). Also, the absence of negative comments can indicate a positive outcome for the submitted article (Thelwall et al., 2020). There is a positive correlation between longer texts and longer sentences, and the positive score of the selection procedures (van den Besselaar & Mom, 2022). Furthermore, project descriptions with a more pronounced narrative structure and expressed self-confidence are more likely to be granted (van den Besselaar & Mom, 2022).

We also found linguistic differences in the peer review reports between the two research areas. Peer review reports for Social Sciences articles had higher scores on several linguistic characteristics: Clout, Authentic, Tone, Agentic, Achievement, Research and Standout. On the other hand, peer review reports for Medical and Health Sciences had higher score on positive evaluation words, i.e. more positive descriptors and superlatives, than the reports in Social Sciences. This is partially in accordance with previous studies that compared peer review reports in social and medical and health sciences. Buljan et al. (2020) found that the language of peer review reports in social sciences journals had high Authenticity and Clout scores, whereas peer review reports in medicine had higher Analytical tone than peer review reports in social sciences. In addition, reviewer recommendations were closely associated with the linguistic characteristics of the review reports, and not to area of research, type of peer review, or reviewer gender (Buljan et al., 2020). Our study, on the other hand, showed that there were differences of the linguistic characteristics of articles and peer review reports between Social Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences. As ORC contains only open peer review reports, the question remains whether there would be differences between open and closed peer review reports. For example, a study showed that closed peer review reports had more positive LIWC Tone compared to open peer review (Bornmann et al., 2012).

One of the novelties that our study brings is the comparison of words used in peer review reports in Social Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences. While Social Sciences peer review reports had more general terms that could be found in other research areas, terminology in Medical and Health Sciences peer review reports was more profession-specific. We visualised these results using clusters to indicate grouping together the closest or most similar words: the closer two words are, the more similar they are, and vice versa. More clusters consisting of specific terms were found in peer review reports in Medical and Health Sciences than in the Social Sciences. This finding actually confirms medical terminology as one of the “oldest specialized terminologies in the world”, having been shaped from Greek and Latin medical writings for over 2000 years (Džuganová, 2019).

Characteristics of the peer review process

We found no statistically significant differences in the duration of the peer review process between Social Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences for articles published in post-publication peer-review platforms. About a half of the articles in both disciplines were approved at the stage of the first version. The reason for this is probably the uniform policy and procedures of the Open Research Central platform, i.e. the same evaluation process for articles in both disciplines. The duration of the peer review process may differ across research areas. A study on 3500 peer review experiences published at the SciRev.sc website revealed significant differences in the duration of the first round and of the total review process across research areas. The first round was of the shortest duration in medicine and public health journals, lasting 8–9 weeks while it was twice as longer in social sciences and humanities, approximately 16–18 weeks (Huisman & Smits, 2017). The study also showed that the total peer review duration in medicine and public health journals was 12–14 weeks, whereas in social sciences and humanities journals about 22–23 weeks (Huisman & Smits, 2017). We also did not find statistically significant differences in other characteristics of the peer review process between the two research areas, such as reviewer’s gender or the number of article versions.

Changes in the manuscript versions

We found that differences between research areas were only statistically significant in the Introduction section, which was the least modified section in the Medical and Health Sciences manuscripts. Some studies examined whether the manuscript versions changed based on the peer review reports. Nicholson et al. (2022) compared linguistic features within bioRxiv preprints to published biomedical texts with aim of examining their changes after peer review. Among predominant changes were typesetting, mentions of supporting information sections or additional files. Another study (Akbaritabar et al., 2022) matched 6024 preprint-publication pairs across research areas and examined changes in their reference lists between the manuscript versions. They found that 90% of references were not changed between versions and 8% were added. The study also found that manuscripts in the natural and medical sciences reframe their literature more extensive, whereas changes in engineering were mostly related to methodology.

Limitations

The limitation of our study is that the Social Sciences articles and peer review reports that we used were mostly from Psychology and Sociology, which have structural similarities to those from Medical and Health Sciences. For example, articles from these two disciplines tend to have IMRaD structure, similar to articles from Medical and Health Sciences. The limitation is also the difference in the sample size as the platform journals still predominantly publish Medical and Health research.

Recommendations

Are the similarities we found between articles in Social Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences a result of their real differences or because the authors had to use the same format of the ORC platforms? The same question applies for the peer review reports. We believe this is due to the latter. For this reason, we recommend that the editors of all ORC platforms take potential structural and linguistic differences between disciplines in consideration. We believe the editors should also consider whether the IMRaD structure is the most appropriate format for each of the disciplines and whether additional formats should be offered.

Conclusion

Due to the different approach, tradition of the writing style and formats typically used in the two compared disciplines, it is not surprising that there are structural and linguistic differences in research articles in Medical and Health Sciences and Social Sciences. However, the review process for articles in Social Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences may not differ as much as is usually considered. This may be due in part to the same platform, which may have uniform policies and processes. With the development of open science practices in social sciences (Christensen et al., 2019), publishing platforms from social sciences and humanities that offer open peer review (Palgrave MacMillan, 2014), those that host multidisciplinary journals (Tracz, 2017; ORC, 2022), and with the evolving role of preprints (Mirowski, 2018) and editorial and review innovations, we can perhaps expect even greater conversion of the article formats and evaluation processes across research areas.

References

Akbaritabar, A., Stephen, D., & Squazzoni, F. (2022). A study of referencing changes in preprint-publication pairs across multiple fields. Journal of Informetrics, 16(2), 101258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2022.101258

Al-Khasawneh, F. (2022). Analysis of the language used in the reports of peer-review journals. Applied Research on English Language, 11, 79–94. https://doi.org/10.22108/are.2022.130458.1774

Bornmann, L., Wolf, M., & Daniel, H.-D. (2012). Closed versus open reviewing of journal manuscripts: How far do comments differ in language use? Scientometrics, 91, 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0569-5

Buljan, I., Garcia-Costa, D., Grimaldo, F., Squazzoni, F., & Marušić, A. (2020). Large-scale language analysis of peer review reports. eLife, 17(9), e53249. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.53249

Buyalskaya, A., Gallo, M., & Camerer, C. F. (2021). The golden age of social science. PNAS, 118(5), e2002923118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002923118

Chen, J. C., Cooper, R. C., McMullen, M. E., & Schriger, D. L. (2017). Graph quality in top medical journals. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 69(4), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.463

Christensen, G., Wang, Z., Levy Paluck, E., Swanson, N., Birke, D., J., Miguel, E., & Littman, E. (2019). Open science practices are on the rise: The state of social science (3S) survey. MetaArxiv Preprints. Preprint. August 2019. Retrieved from https://osf.io/preprints/metaarxiv/5rksu/.

Cooper, R. J., Schriger, D. L., & Close, R. J. H. (2001). Graphical literacy: The quality of graphs in a large-circulation journal. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 40(3), 317–322. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2002.127327

Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587951

Coxhead, A., & Nation, P. (2001). The specialised vocabulary of english for academic purposes. In J. Flowerdew & M. Peacock (Eds.), Research perspectives on english for academic purposes. Cambridge University Press.

Coyle, C. E., Schulman-Green D., Feder, S., Toraman, S., Prust, M. L., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Federal Funding for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences in the United States: Recent Trends. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12(3), 305–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689816662578

Creswell, J. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Džuganová, B. (2019). Medical language – a unique linguistic phenomenon. JAHR - European Journal of Bioethics, 10(1), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.21860/j.10.1.7

Ford, E. (2015). Open peer review at four STEM journals: an observational overview. F1000Research. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.6005.2

Garcia-Costa, D., Squazzoni, F., Mehmani, B., & Grimaldo, F. (2022). Measuring the developmental function of peer review: A multi-dimensional, cross-disciplinary analysis of review reports from 740 academic journals. PeerJ, 10, e13539. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13539

Ghosal, T., Verma, R., Ekbal, A., & Bhattacharyya, P. (2019). DeepSentiPeer: Harnessing sentiment in review texts to recommend peer review decisions. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, presented at the ACL 2019, Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, pp. 1120–1130.

Hamilton, D. G., Fraser, H., Hoekstra, R., & Fidler, F. (2020). Journal policies and editors’ opinions on peer review. eLife, 9, e62529. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62529

Hren, D., Pina, D. G., Norman, C. R., & Marusic, A. (2022). What makes or breaks competitive research proposals? A mixed-methods analysis of research grant evaluation reports. Journal of Informetrics, 16(2), 101289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2022.101289

Huisman, J., & Smits, J. (2017). Duration and quality of the peer review process: The author’s perspective. Scientometrics, 113(1), 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2310-5

Jaffe, K. (2014). Social and natural sciences differ in their research strategies, adapted to work for different knowledge landscapes. PLoS One, 9(11), e113901. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113901

JASP Team (2020). JASP (Version 0.14.1) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://jasp-stats.org/.

Jurafsky, D., & Martin, H.J. (2000). Speech and language processing: an introduction to natural language processing, computational linguistics, and speech recognition. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-095069-7. Retrieved from https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/ed3book.pdf.

Jürgen, H. (1968). Erkenntnis und Interesse. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1968

Kaatz, A., Magua, W., Zimmerman, D. R., & Carnes, M. (2015). A quantitative linguistic analysis of national institutes of health R01 application critiques from investigators at one institution. Academic Medicine, 90(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000442

Karhulahti, V. M., & Backe, H. J. (2021). Transparency of peer review: A semi-structured interview study with chief editors from social sciences and humanities. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 6(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-021-00116-4

Khatwani, M. K., & Panhwar, F. Y. (2019). Objectivity in social research: A critical analysis. Asia Pacific, 37, 126–142.

Kronick, D. A. (1976). A history of scientific & technical periodicals: The origins and development of the scientific and technical press (pp. 1665–1790). Scarecrow Press.

Levenshtein, V. I. (1966). Binary codes capable of correcting deletions, insertions and reversals. Soviet Physics Doklady, 10(8), 707–710.

Lewis, R. W. (1988). Biology: A hypothetico-deductive science. The American Biology Teacher, 50(6), 362–366.

McCall, J. (2015). Format, flexibility, and speed. The Academic Book of the Future. Retrieved from https://academicbookfuture.org/2015/06/12/format-flexibility-and-speed-palgrave-pivot/.

Mirowski, P. (2018). The future(s) of open science. Social Studies of Science, 48(2), 171–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312718772086

Ngai, S. B. K., Gill Singh, R., & Chun Koon, A. (2018). A discourse analysis of the macro-structure, metadiscoursal and microdiscoursal features in the abstracts of research articles across multiple science disciplines. PLoS One, 13(10), e0205417. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205417

Nicholson, D. N., Rubinetti, V., Hu, D., Thielk, M., Hunter, L. E., & Greene, C. S. (2022). Examining linguistic shifts between preprints and publications. PLoS Biology, 20(2), e3001470. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001470

Open Research Central (ORC). (2022). Retrieved from https://openresearchcentral.org/

Palgrave Macmillan. (2014). Retrieved from https://palgraveopenreview.wordpress.com/

Pennebaker, J. W., Booth, R. J., Boyd, R. L., & Francis, M. E. (2015). Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC2015a. Pennebaker Conglomerates.

Pennebaker, J. W., Boyd, R. L., Jordan, K., & Blackburn, K. (2015b). The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2015. University of Texas at Austin.

Pennington, J., Socher, R., & Manning, C.D. (2014). GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 1 October 2014. https://doi.org/10.3115/v1/D14-1162

Plano Clark, V., & Ivankova, N. (2016). Mixed methods research: A guide to the field. SAGE Publications.

Plano Clark, V. L. (2010). The Adoption and Practice of Mixed Methods: U.S. Trends in Federally Funded Health-Related Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364609

Puzzo, D., & Conti, F. (2021). Conceptual and methodological pitfalls in experimental studies: An overview, and the case of alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 15(14), 684977. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2021.684977

Rashidi, K., Sotudeh, H., Mirzabeigi, M., & Nikseresht, A. (2020). Determining the informativeness of comments: A natural language study of F1000Research open peer review reports. Online Information Review, 44(7), 1327–1345. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-02-2020-0073

Ross-Hellauer, T. (2017). What is open peer review? A systematic review. F1000Research, 6, 558. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11369.2

Salganik, M.J. (2019). Bit by Bit: Social research in the digital age. Princeton University Press, SBN: 9780691196107.

Savage, W. E., & Olejniczak, A. J. (2022). More journal articles and fewer books: Publication practices in the social sciences in the 2010’s. PLoS One, 17(2), e0263410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263410

Schmader, T., Whitehead, J., & Wysocki, V. H. (2007). A linguistic comparison of letters of recommendation for male and female chemistry and biochemistry job applicants. Sex Roles, 57(7–8), 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9291-4

Schriger, D. L., Raffetto, B., Drolen, C., & Cooper, R. J. (2017). The Effect of Peer Review on the Quality of Data Graphs in Annals of Emergency Medicine. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 69(4), 444–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.06.046

Silverberg, O., & Ray, J. G. (2018). Variations in instructed vs. published word counts in top five medical journals. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(1), 16–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4196-6

Skicit learn 2022. Retrieved from https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.manifold.TSNE.html

Sollaci, L. B., & Pereira, M. G. (2004). The introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD) structure: A fifty-year survey. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 92(3), 364–371.

Squazzoni, F., Ahrweiler, P., Barros, T., Bianchi, F., Birukou, A., Blom, H., Bravo, G., Cowley, S., Dignum, V., Dondio, P., Grimaldo, F., Haire, L., Hoyt, J., Hurst, P., Lammey, R., MacCallum, C., Marušić, A., Mehmani, B., Murray, H., Nicholas, D., … Willis, M. (2020). Unlock ways to share data on peer review. Nature, 578(7796), 512–514. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00500-y

Squazzoni, F., Bravo, G., Farjam, M., Marusic, A., Mehmani, B., Willis, M., Birukou, A., Dondio, P., & Grimaldo, F. (2021). Peer review and gender bias: A study on 145 scholarly journals. Science Advances. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd0299

Squazzoni, F., Bravo, G., Grimaldo, F., García-Costa, D., Farjam, M., & Mehmani, B. (2021). Gender gap in journal submissions and peer review during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. A study on 2329 Elsevier journals. PLoS One, 16(10), e0257919. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257919

Steffens, A. N. V., Langerhuizen, D. G. W., Doornberg, J. N., Ring, D., & Janssen, S. J. (2021). Emotional tones in scientific writing: Comparison of commercially funded studies and non-commercially funded orthopedic studies. Acta Orthopaedica, 92(2), 240–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2020.1853341

Thelwall, M., Papas, E.-R., Nyakoojo, Z., Allen, L., & Weigert, V. (2020). Automatically detecting open academic review praise and criticism. Online Information Review, 44(5), 1057–1076. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2019-0347

Timans, R., Wouters, P., & Heilbron, J. (2019). Mixed methods research: What it is and what it could be. Theory and Society, 48, 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-019-09345-5

Tracz, V. (2017). ORC – Open Research Central: ‘repulsive and malevolent’ or ‘lover of rebellion and freedom’. F1000 blognetwork. Retrieved from https://blog.f1000.com/2017/07/12/orc-open-research-central-repulsive-and-malevolent-or-lover-of-rebellion-and-freedom/.

Trix, F., & Psenka, C. (2003). Exploring the color of glass: letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse & Society, 14(2), 191–220.

van den Besselaar, P., & Mom, C. (2022). The effect of writing style on success in grant applications. Journal of Infometrics, 16, 101257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2022.101257

van der Maaten, L. J. P., & Hinton, G. E. (2008). Visualizing data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 9, 2579–2605.

Vincent-Lamarre, P., & Larivière, V. (2021). Textual analysis of artificial intelligence manuscripts reveals features associated with peer review outcome. Quantitative Science Studies, 2(2), 662–677. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00125

Wang, K. & Wan, X. (2018). Sentiment analysis of peer review texts for scholarly papers, The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, pp. 175–184.

Wiktionary, the free dictionary: Frequency lists. (2006). Retrieved from https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Wiktionary:Frequency_lists/PG/2006/04/1-10000.

Williams, P., Stevenson, I., Nicholas, D., Watkinson, A., & Rowlands, I. (2009). The role and future of the monograph in arts and humanities research. Aslib Proceedings, 61(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530910932294

Woiceshyn, J., & Daellenbach, U. (2018). Evaluating inductive vs deductive research in management studies: Implications for authors, editors, and reviewers. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management, 13(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-06-2017-1538

Wolfe, A. (1990). Books vs. articles: Two ways of publishing sociology. Sociological Forum, 5(3), 477–489.

Wu, J. (2011). Improving the writing of research papers: IMRAD and beyond. Landscape Ecology, 26, 1345–1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-011-9674-3

Funding

This research received funding from the Croatian Science Foundation within the framework “Professionalism in Health: decision-making in health and research”—Pro Dem under Grant Agreement No [IP-2019-04-4882].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The Authors confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perković Paloš, A., Mijatović, A., Buljan, I. et al. Linguistic and semantic characteristics of articles and peer review reports in Social Sciences and Medical and Health Sciences: analysis of articles published in Open Research Central. Scientometrics 128, 4707–4729 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04771-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04771-w