Abstract

There is increasing interest within Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to examine curricula for legacies of colonialism or empire that might result in a preponderance of references to research from the global north. Prior attempts to study reading lists for author geographies have employed resource-intensive audit and data collection methods based on manual searching and tagging individual reading list items by characteristics such as author country or place of publication. However, these manual methods are impractical for large reading lists with hundreds of citations that change over instances the course is taught. Laborious manual methods may explain why there is a lack of quantitative evidence to inform this debate and the understanding of geographic distribution of curricula. We describe a novel computational method applied to 568 articles, representing 3166 authors from the Imperial College London Masters in Public Health programme over two time periods (2017–18 and 2019–20). Described with summary statistics, we found a marginal shift away from global north-affiliated authors on the reading lists of one Masters course over two time periods and contextualise the role and limitations of the use of quantitative data in the decolonisation discourse. The method provides opportunities for educators to examine the distribution of course readings at pace and over time, serving as a useful point of departure to engage in decolonisation debates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, staff and students at different Higher Education institutions (HEIs) in the UK and globally have attempted to identify colonial legacies in different interpretations of the term ‘decolonisation’. Though some argue that the term is being appropriated and applied more as metaphor than anything else (Tuck & Yang, 2012) or believe that HEIs reproduce colonial logic, and so no HEI can truly dismantle colonialism (Grewal, 2021), a majority agree that action must be taken, and that there will be no one single approach that on its own constitutes ‘decolonisation’ (de Oliveira Andreotti et al., 2015). Some groups have focused on iconography and buildings named after persons with a colonial history (Chumani Maxwele Ignites the #RhodesMustFall Movement at UCT, 2015; Decolonise UCL, n.d.; #RHODESMUSTFALL, n.d., 2018). Others have focused on the curriculum white?, http://www.dtmh.ucl.ac.uk/videos/curriculum-white/ (UCL 2014) (English Faculty Begins Decolonisation Discussion, 2017; Gishen & Lokugamage, 2018; University of Westminster, 2020). Broadly, these movements can be understood as responses to decolonisation theories of epistemological racism in academia (Kubota, 2020), ‘asymmetric ignorance’ (western academics can afford to not cite non-western academics, without this affecting the perceived quality of their work, but non-western academics are not afforded this) (Chakrabarty, 2000) or a need for cognitive justice within the global academic community where “the norm is [a] plurality of knowledge” (Coimbra, 2007).

Epistemological racism impeding the equitable diffusion of knowledge and research from Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to High-income countries (HICs) has been observed in our global public health research (MS & MH). Cases of frugal medical innovations, which can often originate in LMICs, are in many instances met with barriers, including prejudice, when introduced in HIC settings (Harris et al., 2015, 2016). Indeed, we have argued that the non-use of some frugal innovations in HICs, which could be associated with significant cost-savings to systems such as the NHS, amounts to a double-standard (Skopec et al., 2019; Skopec, Fyfe, et al., 2021; Skopec, Grillo, et al., 2021). Additionally, we have found that narratives which aim to promote mutual and reciprocal learning between HICs and LMICs in international health partnerships are frequently underscored by power dynamics that position LMIC partners as recipients of knowledge, rather than as producers, hampering the bi-directional nature of these partnerships (Issa et al., 2017; Kulasabanathan et al., 2017). We draw parallels between resistance to use of frugal innovation developed in LMICs to the country of origin (COO) effect, studied extensively in consumer economics. Consumers evaluate products differently based on their COO and products from LMICs are generally rated less favourably due to the external cue of COO (Adina et al., 2015; Bilkey & Nes, 1982; Srinivasan et al., 2004; Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999).

While COO effects have been extensively studied for physical products such as cars, wine or electronics (Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999), they may also extend to intellectual products, such as scientific research. For example, the country in which the research is produced and the institutional affiliation of the authors may be interpreted by consumers as an indicator of the quality of that research by unconscious bias (Harris et al., 2017a) or explicit bias (Harris et al., 2017b). Under controlled conditions, it has been demonstrated that research produced in HICs is evaluated more favourably than the same research produced in LMICs (Harris et al., 2017a, 2017b), adjusted for other characteristics. It is possible that the COO effect thus might also influence selection of texts for curricula.

This claim can be investigated in the context of global research production and consumption markets. One relevant factor in the research production market is the trend of local publishing models such as academic, society or library publications with regional authorship and/or readership commodified or acquired by multinational enterprise (Collyer, 2018). Authors are then faced with the choice of publishing in these commodified journals, perhaps also under pressure to participate in global north-derived indicators of research success such as journal indexing or metrics; or risk invisibility in the remaining local or ‘periphery’ publishing venues (Salager-Meyer, 2008). The publishing monopoly has also led to inflated subscription and publication costs, making participation for scholars in the global south prohibitively expensive (Collyer, 2018). This, in combination with other issues such as English language dominance, contributes to a barrier for global south researchers wishing to penetrate the centralised global north market (Collyer, 2018) as well as disinclining readers from across the world to seek out and read journals published outside of the global north (Salager-Meyer, 2008). Citation networks as indicators of influence also demonstrate a gap in the consumption of global scientific research Cash-Gibson et al., 2018; Gálvez et al., 2000; Keiser et al., 2004; Pan et al., 2012). A 2012 analysis found that North America and Europe receive 42.3% and 35.3% of the world’s citations, respectively, compared to less than 5% by Africa, South America and Oceania combined (Pan et al., 2012). A 2019 analysis found that more than 75% of social science articles indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) database originated in either America or Western Europe, with the combined global south representing less than 10% (Demeter, 2019). Scholars of the global north are self-citing and inward-looking, while their colleagues in the global south primarily also cite research from ‘core countries’ (such as the UK and the US), rather than their own (Collyer, 2018).

There are also factors of practical accessibility of texts to libraries and readers such as book and journal pricing, translation availability and import/export availability for different purchasing markets or consortiums that might affect representation in reading lists. Librarians at the London School of Economics found that 98.38% of all books and chapters of all course reading lists for the academic year 2019–20 were published by publishing houses based in global north countries, with 87.77% of this represented by the UK and US (Wilson, 2019). A 2019 analysis of two module reading lists at another UK university suggested that reading lists were dominated by white, male, Eurocentric authors (Schucan Bird & Pitman, 2019). Another study found that the reading lists of one University of Sussex faculty’s reading lists comprised 39.36% and 31.97% of material published by publishers in the USA and UK respectively (Taylor et al., 2021).

Our study is in reference to decolonisation theory, but we use the term ‘geographic bias’ as we do not wish to claim that this work in isolation can ‘decolonise’ a reading list or an institution. Firstly, the analysis we present is purely descriptive, and cannot determine the cause of any skew or imbalance. Secondly, the analysis is at country-level affiliation and excludes race as a factor. The country-level analysis is derived from our research question’s origin in COO effect and reverse innovation studied at country-level. This perspective excludes the role of race in forming identities and the wider modern world. We acknowledge that excluding race as a factor could be understood as ‘methodological whiteness’ (Bhambra, 2017). Additionally, whilst we propose a quantitative method as a unique and valuable contribution to the wider decolonisation debate, particularly for STEM disciplines and institutions (Skopec, Grillo, et al., 2021) we strongly advocate it should not guide educator choice, rather it can be helpful to have data to for understand distribution and changes over time. If the data is applied with intention to use for decolonisation purposes—however they are defined—it should only be supplementary to qualitative and experience-led methods such as reflection toolkits, discussion groups, surveys and more that are already being deployed by some HEIs.

Quantitative analysis of reading lists is not yet widely used by course leaders, librarians or HEIs for diversity or decolonisation efforts. Open Syllabus aggregates publicly-available reading lists to indicate the most frequently assigned titles and trends in institutional and national level reading list title selection, but it does not, at present, display data on author affiliation geography (Open Syllabus, 2020). Our method was created due to the lack of pre-existing alternative end-to-end reading list analysis tools available to us. Institutions wishing to perform their own analysis are effectively left to use manual search and coding methods to retrieve data and analyse it. Manual methods were used by ourselves prior to the creation of this method, and by the LSE and UCL-authored studies of reading lists, in which the latter concluded that “Universities need to invest in research to develop and trial methods for interrogating diversity in module reading lists” (Schucan Bird & Pitman, 2019). A study of gender bias in curricula at Washington University in St Louis produced a method of coding based on Application Programme Interfaces (APIs) (Harris et al., 2020) that, whilst advancing on resource-intensive manual methods deployed by previous studies (Phull et al., 2019), also call for “Development of more sophisticated technological tools for automating the examination of syllabi might be a longer-term and more resource intensive solution” (Harris et al., 2020).

We have devised a computational method that permits semi-automated analysis of the geographical distribution of reading list authors. The method generates a quantitative indicator that facilitates time-specific and evidence-based interpretations of the data that can be used to supplement experience and theory-led decolonisation work. In this article, we describe the methods used to convert reading lists of the Imperial College London Masters in Public Health (MPH) programme over two time periods (2017–18 and 2019–20) into machine readable code from which bibliographic and author region data is retrieved from the WoS and country socioeconomic status is retrieved from the World Bank. Using 1,200 citations we describe the shift in geographic bias of reading list sources and relate this to interventions to decolonise the curriculum at Imperial College London during that period.

Methodology

We chose to analyse the MPH program as MH is a course co-Director, permitting a certain amount of ‘academic jurisdiction’ over the reading lists and because efforts to engage faculty in the MPH programme with decolonisation debates had been active since 2018. Additionally, MPH programmes offer a varied subject matter drawing on geographically diverse research topics and therefore there was empirical interest to see if reading lists reflected that to some degree. Data was retrieved from two sources, (1) Leganto Reading Lists (Leganto Reading Lists, n.d.) (henceforth “Leganto”), a digital reading list management system and (2) the Web of Science Core Collection (henceforth WoS) (‘Web of Science Core Collection’, n.d.).

Stage 1—retrieve items from reading list management system

We searched Leganto using Oracle Business Intelligence Enterprise Edition for “Academic Department Description" = “School of Medicine” AND “Course Year" = ‘2018' or '2019' or '2020'. This search retrieved data associated with all courses in the School of Medicine faculty. The SQL request can be found in Supplementary Data under “Stage One SQL script”.

Stage 2—retrieve author-specific bibliographic data

A PHP script imports the data from each file in this folder and makes a separate curl HTTP request to the WoS database for each reading list item via a GET command to the WoS API Expanded. The full PHP script is available in Supplementary Data “Stage 2 PHP input.txt” and an example of the GET command format in “Stage 2 GET script example”. Relevant bibliographic fields were extracted from the XML of matched responses from the WoS response and merged with the Leganto extract of Stage 1, then exported to a CSV file format.

Stage 3—retrieve country socioeconomic indicator

We used the World Bank Atlas Method, a rank of countries based on the Gross National Income (GNI) per capita (Atlas Method)(GNI per Capita, Atlas Method (Current US$) | Data, n.d.), to attribute numeric value to citations based on the distribution of authors’ affiliated country socio-economic status. See Discussion for rationale of selecting this indicator.

Stage 4—transform data

We matched World Bank regions to WoS author affiliation regions. 40 data points were removed as they were geographic regions that came from the WoS author country field that either did not refer to a country for which World Bank data was available (such as “Arab World”, “Middle East and Northern Africa” or “Latin America & Caribbean”), or the World Bank classification returns no data (Andorra, Gibraltar or Monaco, among others). This left a remainder of 203 countries, ranked by income. For 184 countries, income data from 2018 was used. For 19 countries, 2018 data was not available, and the most recent available data was used instead. These countries are listed in Supplementary Data “World Bank_GNI per capita_2020_.xls”.

The CSV files generated in Stages 2 was also subject to data cleansing. The WoS CSV file ambiguates all author country data into a single cell and so must be disambiguated into a cell per author. It was only possible to extract the first listed affiliation from multi-affiliated authors. The country of each author’s affiliation was then replaced with its corresponding inverse rank according to the GNI/capita ranking. For instance, “Australia” was replaced with its corresponding rank, 188. Where WoS disambiguates author territories in a different way to the World Bank, but both were identifiable, we compressed the regions to match the World Bank schema, e.g. WoS disambiguates “England,” “Wales,” “Scotland” and “Northern Ireland” separately, whereas World Bank includes all under “United Kingdom” and all are assigned the same rank, 179. The percentile ranking was then used to calculate the Citation Source Index as described below.

Citation source index

From the Leganto, WoS and World Bank inverse ranking percentile we calculated a Citation Source Index (CSI). This CSI represented a weighted average of the World Bank rankings for GNI/capita of the countries where the authors in that citation were from. A formula for the CSI can be seen in Eq. 1. The equation denominator is fixed at 203 because there were 203 countries identified from the World Bank ranking.

Equation 1. Citation Source Index (CSI). The CSI provides a weighted score for each individual citation, based on the citation’s author’s institutional affiliations. The closer the CSI is to 1, the more high-income countries are represented on a given citation.

Based on this calculation, a CSI could be any value between 0.0049 (for a citation with authors exclusively from Somalia, ranked at number 1 on the GNI/capita list) and 1 (for a citation with authors exclusively from Liechtenstein, ranked number 203 on the GNI/capita list). A CSI closer to 1 would represent authorship primarily affiliated with institutions in HICs, whereas a CSI closer to 0.0049 would represent authorship primarily affiliated with institutions in LICs. Calculating a CSI for each module on the course, as well as calculating an aggregate CSI for both the 2017–18 and 2019–20 course, permits easy visualisation to describe any changes in the geographical distributions of the reading lists.

Findings

Data were analysed at the course and module level. Module codes have been de-identified. Box and whiskers plots were generated to allow for simple visualisation of the median CSI, the interquartile range (IQR), as well as outliers on the course or module. Below, we discuss the 2017–18 and 2019–20 results individually. We also evaluate outliers and discuss potential reasons for the discrepant scores and compare the changes in CSI for specific modules.

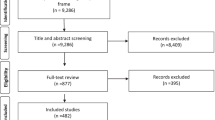

‘Missing’ data

Not all reading list items from the 2017–18 and 2019–20 MPH could be represented in the analysis because we only extracted journal article data from the WoS. For example, the 2017–18 dataset consisted of 660 total citations and 354 (53.63%) of these citations were journal articles and were therefore viable for analysis. The 2019–20 dataset consisted of 553 total citations, however three modules did not have their reading lists published on Leganto, so data for these modules could not be retrieved, resulting in a smaller sample size compared to 2017–18. 314 (56.78%) of the 2019–20 citations were journal articles and were therefore viable for analysis.

For the 2017–18 dataset, of the 354 journal articles 37 (10.45%) articles did not generate data through WoS. An additional 3 articles (0.84%) were excluded as the authors did not have affiliations listed on WoS, or because the country of affiliation was not listed in the World Bank’s ranking, examples of this include “Taiwan” or “Occupied Palestinian Territories.” 314 articles (or 89.54% of the viable articles containing DOIs) were included in the final analysis.

For the 2019–20 dataset, of the 323 journal articles 65 (20.70%) articles did not generate data through WoS. An additional 4 articles (1.274%) were excluded from analysis because authors did not have an affiliation listed on WoS, or because the country of affiliation was not listed in the World Bank’s ranking. 254 articles (or 80.89% of the viable articles containing DOIs) were included in the final analysis. Figure 1 depicts a flowchart of this breakdown.

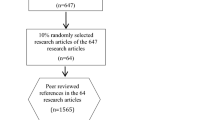

Manual spot-checks of 10% of citations for each year were undertaken to ensure that no errors existed in the country affiliation data. Citations were picked using a random number generator created in Excel. For 2017–18, one citation (0.318% of the total included for that year) only retrieved information for one author, despite there being five authors on the paper. As all authors were affiliated with institutions in the UK, this did not change the CSI. For 2019–20, one citation (0.394% of the total included for that year) was attributed to an author affiliated with an institution in Kenya, but spot-checking revealed that they were in fact affiliated with an institution in the UK. This was an error attributed to WoS indexing which has since been corrected by WoS and corrected in our dataset. Aside from these errors, no additional errors were found. Tables 1 and 2 show a module-by-module breakdown of total viable citations for the study, percentage of viable citations not found by the WoS and the total authors represented.

Results

314 citations were analysed for the 2017–18 reading lists, comprising 1566 authors. The median CSI for 2017/18 was 0.8818 (IQR 0.8818–0.9498). The mean CSI was 0.8837, the maximum was 0.9901, and the minimum was 0.4712. 254 citations were analysed for the 2019–20 reading lists, comprising 1342 authors. The median CSI for 2019/20 was 0.8818 (IQR 0.8818–0.9557). The mean CSI was 0.8803, the maximum was 0.9901, and the minimum was 0.4778. We also compared the composition of several modules between 2017–18 and 2019–20, to establish whether there was a shift in the geographic distribution of selected articles over this time period. Figure 2 shows a comparison of CSI scores for the course overall, as well as for the individual modules that were analysed.

Comparison of CSI scores from 2017-18 and 2019-20. The above graph depicts a comparison of aggregate CSI scores for the 2017-18 and 2019-20 MPH course (“ALL”), as well as a comparison of individual modules. MC2019-20, MJ2019-20, MK2019-20, and MP2017-18 and 2019-2020 did not contain citations for analysis. This is discussed further in the Limitations section

A skew toward research produced in countries in the global north is observed. However, the course median CSI did not change between 2017–18 and 2019–20 (0.8817), though mean CSI was slightly lower in 2019–20 (from 0.8837 to 8.8803, a decrease by 0.0034 points). There was also very little change in CSI at the module level. Both median and mean scores remained similar over the two-year time interval. Median CSI decreased in four modules, ME2017-18/2019–20 (N = 27 and 26 citations, respectively), ML2017-18/2019–20 (N = 2 and 2 citations, respectively), MM2017-18/2019–20 (N = 9 and 8 citations, respectively) and MN2017-18/2019–20 (N = 38 and 37 citations, respectively). The median CSI was lowered by 0.0167, 0.0026, 0.083 and 0.0099 points, respectively. Median CSI increased for MA2017-18/2019–20 and MH2017-18/2019–20 by 0.0739 and 0.0114, respectively. For the remaining three modules, median CSI remained the same.

Mean CSI decreased in MB2017-18/2019–20 (N = 16 and 1, respectively), ME2017-18/2019–20 (N = 27 and 26, respectively), MI2017-18/2019–20 (N = 17 and 12, respectively), ML2017-18/2019–20 (N = 2 and 2, respectively), MM2017-18/2019–20 (N = 9 and 8, respectively), and MO2017-18/2019–20 (N = 11 and 7, respectively). Mean CSI decreased by 0.0034 overall, and by 0.0035 (MB2017-18/2019–20), 0.0005 (ME2017-18/2019–20), 0.0059 (MI2017-18/2019–20), 0.083 (ML2017-18/2019–20),0.0585 (MM2017-18/2019–20) and 0.0209 (MO2017-18/2019–20) for the modules. On the other hand, mean CSI increased for MA2017-18/2019–20 (0.0009), MD2017-18/2019–20 (0.0044), MF2017-18/2019–20 (0.0096), MG2017-18/2019–20 (0.0024) MH2017-18/2019–20 (0.0047), and MN2017-18/2019–20 (0.0135).

Overall, the modules continued to display a skew toward research produced by authors affiliated with institutions in HICs. However, though the CSI scores indicate both median and mean scores centred nearer to 1, the long ‘tails’ in Fig. 2 indicate that most modules do still include a variety of citations, including some with authors affiliated with institutions in LICs. Particularly in the example of MI2017-18/2019–20, the ‘addition’ of a tail between the two points in time may seem to indicate a greater geographic diversity of readings, and more inclusion of research with authors from LICs. Indeed, the minimum score for this module shifted from 0.8818 in 2017–18 to 0.775 in 2019–20, following the addition of a paper featuring a collaboration between authors from the US, the UK, Ireland and South Africa. Yet, the opposite appears to be true for MF2017-18/2019–20, as there are very narrow tails, and there appears to have been no addition of citations featuring LIC authors between the two time points.

ME2017-18 contains the citation with the lowest score for 2017–18. This citation (India’s Conditional Cash Transfer Programme (the JSY) to Promote Institutional Birth: Is There an Association between Institutional Birth Proportion and Maternal Mortality?, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067452) features a collaboration between two authors based at RD Gardi Medical College in Ujjain, India, and one author based at Karolinska Institutet in Umea, Sweden. However, this citation was not present in the 2019–20 reading list. MN2017-18/2019–20 contains the citation with the lowest score for 2019–20 (0.477833). This citation (Barriers for Adopting Electronic Health Records (EHRs) by Physicians, https://doi.org/10.5455/aim.2013.21.129-134) features a co-authorship between two authors at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran.

Discussion

As far as we are aware, the methods detailed in this paper are the first to connect a reading list management programme, a bibliographic database and World Bank data in a semi-automated method and could be a useful way to analyse at scale and pace the distribution of socioeconomic country status of authors in reading lists. The lack of significant change in CSI at course and module level is unsurprising given efforts to engage faculty responsible for this course with debates surrounding decolonisation began in earnest only at the end of 2018. It also indicates that literatures included in postgraduate courses are relatively static over time and a concerted effort would be required to effect a significant shift in reading list compositionNevertheless, data visualisation is useful to explore trends and stimulate debate, particularly in fields that are used to quantitative or statistical process. We believe that this quantitative approach can complement, not replace, a qualitative enquiry and reflection on the geographic diversity of a reading list. Commenting on the lack of decolonisation discussion in STEM fields, Shahjahan et al. ask “What is the nature of some disciplines that afford decolonization praxis?” (Shahjahan et al., 2021). Perhaps a scalable, reproducible and data led response such as ours might respond to something in the nature of STEM fields. As a dataset it is only a point of departure and the real work of decolonisation requires individuals and institutionsto reflect and challenge.

The results of the MPH analysis indicate a skew toward research produced by researchers affiliated with institutions predominantly in HICs. Our findings are broadly reflective of the global research production landscape, which itself is heavily skewed toward the global north, as demonstrated by others (Cash-Gibson et al., 2018; Pan et al., 2012). However, we cannot state for certain whether the skew in the reading lists we observed is because of that broader pattern. The descriptive nature of our analysis does not allow us to determine whether articles from the global south that were added to the reading list in 2019–20 have been thoughtfully incorporated into the taught curriculum, or if they have been included, consciously or not, in anticipation of the CSI measurement in this project. Our quantitative method cannot meaningfully answer questions of motivation and therefore it cannot determine changes in attitudes.

Whilst a shift in the CSI of a course over time from a value closer to 1 to a value closer to 0.0049 would suggest that the geographic distribution of a reading list’s authors included a greater proportion of authors affiliated with institutions in LICs, the CSI is merely one way to describe a reading list. It is not intended to be a score of the reading list. Rather, it is intended to provide a baseline to assess the geographic composition of reading lists and a method to assess trends and changes over time. The CSI can give an indication of geographic representation and diversity that can support, but should not lead, qualitative and theoretical interpretation. This data is only of real value if it can be meaningfully interpreted by subject matter experts who can decide if (a) there is need or desire for a geographic based ‘liberation lens’ (Charles, 2019) to be applied to this course; (b) if the material is appropriate for this method and its limitations; and finally (c) to decide if the results are meaningful. To understand whether the results are meaningful could include for example, if the result is simply representative of the realities of research production in this subject, e.g. high energy physics research will be conducted in locations with these facilities. Other ways to contextualise the results could include the location of the HEI, the composition of the taught student body and more. We are using the results of the single course analysis to begin conversations across Imperial College London to find groups interested to apply an empirical perspective to their curriculum and interpret the results meaningfully.

The application of gender assessment methods (Sumner, 2018) could be combined with our method to examine intersections of geographic and gender bias, as some other studies have also done so (Taylor et al., 2021). There is also a need to consider broader issues than just country affiliation, including representation and experience in academic careers (Arday, 2020), diversity in the academic library and publishing sectors (Charles, 2019) and intersections with gender (Harris et al., 2020) or other characteristics. Our study does not categorise based on language, for the pragmatic reason that all the reading list items found were in English and the primary language of instruction in the institution is English. However, non-English language texts were not de facto excluded and would, if indexed by WoS and containing a DOI, have been present in the results. The question of identifying reading list texts that had been originally published in another language and translated into English could be particularly valuable for future research to consider.

Other initiatives towards decolonisation at Imperial College London include a half-day faculty workshop, held in collaboration with the Educational Development Unit (EDU) on a biannual basis, which aims to provide a space for faculty and staff to have facilitated discussions surrounding this topic. Not coincidentally, this very research project arose as a result of several members of the library staff (including CN) attending one of these workshops facilitated by MH and MS. We have designed a bespoke Implicit Association Test (IAT), which measures respondents’ unconscious associations between “Good and Bad Research” and “High- and Low-income countries.” To date, 201 members of the Imperial College London community have taken the test. The median D-Score (the measure of unconscious bias) of 0.527 (95% CI–0.249; 1.302), suggests a “Moderate” unconscious association between HICs and “Good research” among participants. A detailed discussion of the IAT methods we used have been documented elsewhere (Harris et al., 2017a, 2017b). Information Literacy teaching provision from the library is underpinned by the A New Curriculum for Information Literacy (ANCIL) framework (McConnell, 2011) and has been reviewed to ensure delivery of the Critical Analysis competency to recognise bias in authors and intellectual movements. A Decolonise the Library working group has been formed. In October 2021, Imperial College published the conclusions of an independent History Group commissioned to review the institution’s history and legacies. The recommendations include in some cases renaming or providing education on buildings, funds or awards named after figures determined by this group to be associated with race science, eugenics, slavery or the British Empire and advocating honorary action to recognise underappreciated individuals (Dialogue Begins as Community Confronts, Celebrates and Learns from Past|Imperial News|Imperial College London, n.d.). Other initiatives include mentoring and scholarships aimed at supporting black British students, a group indicated as underrepresented at the institution, have also be installed.

Limitations

Identifying reading list material is dependent on course leaders having correctly registered the items by DOI in Leganto, a manual process and thus open to human error. Any reading list items not captured by course leaders in Leganto, e.g. items communicated to students outside of the official course reading list system, were not retrievable. Items that do not have a DOI cannot return data. This excluded output types other than journal articles from the analysis. For the reading lists concerned, the commonly excluded output types included books, book chapters, grey literature such as presentation files, health policy reports and websites (see Fig. 1). For this reason, this method would not be appropriate for courses with reading lists with a majority non-journal article outputs. In our study, this was the case for MP2017-18/2019–20, which relied only on textbooks, and was therefore excluded. However, as shown in Fig. 2, more than 50% of all readings for both 2017–18 and 2019–20 were still viable for analysis.

WoS introduces several limitations. Firstly, as a paid-for and biased (it is a self-selective, not comprehensive database) source it could be introducing its own biases into method. A crucial data field returned by WoS in Stage 2, the Author Sequence (“addr_no”) permits the authors to be identified by their numerical positioning in the manuscript author list. This data field is not regularly supplied by WoS for items published before 2008. This affected 91 items for all reading list years studied in this analysis. A further 20 records returned null results because the journals they were published in are not indexed by WoS. It was used in our study as a stable data source that we were familiar with to write the scripts for, experiment with and have access to large download limits with through our institutional subscription. Future research would benefit from using an alternative database to WoS that is free to access and comprehensive.

The World Bank’s GNI per capita ranking is generally regarded as a robust indicator of country income. However, we acknowledge, as the World Bank themselves have done, that the classification terms it relies on (Low Income, Middle Low Income, etc.) could be arbitrary, unhelpful or outdated (Khokhar & Serajuddin, 2015). In fact, these terms can be deterministic and even detrimental to the country’s economic prospects when applied. Though less normative classifications are emerging to describe economies (such as the ‘fat’ and ‘lean’ monikers (Olopade, 2014), few have yet to catch on. However, we find country income status to be a useful indicator because of the links between COO and consumption of research (Harris et al., 2017a, 2017b). Additionally, when testing respondents’ subconscious associations between research from “Rich Countries” and whether that research is of “Good” quality using Implicit Association Tests, bias advantaging HICs persists (Harris et al., 2017a, 2017b). As a point of departure to understand general trends in the articles selected for use on a curriculum, country income status is a potentially useful measure to generate general discussion and reflection on choices made around included literature and the underlying trends in global research production and consumption. Our study analysed author identity only as assigned country of authors as declared on the published manuscript. For example, all authors affiliated to UK institutions are assigned rank 179. An author at a UK institution could originate from an LMIC and could thus contribute a different perspective than their co-authors from the UK, but our methodology is not able to account for this, or other identity characteristics and experiences such as race. We acknowledge that this may reflect our own influences in western academia and miss an opportunity for deeper understanding of race or other structural processes affect curricula and education decisions (Bhambra, 2017). Our method also cannot assess the textual meaning of the papers on reading lists. So, even though a study may have been authored by researchers in HICs, it could contain content that is valuable to a decolonial perspective. Application of natural language processing to items on reading lists could potentially provide semantic analysis (Atanassova et al., 2019) at this scale. Place of Publication is a relevant bibliographic field available for analysis used by other studies (Taylor et al., 2021; Wilson, 2019). We chose not to use the field in this study as we believe author country affiliation is a more meaningful indication of author identity/background and potential connection to the COO effect and geographic bias than location of publisher.

Conclusions

We found that for both time periods, citations on the reading list were authored primarily by institutions in HICs, and there was a marginal reduction in CSI from the 2017–18 course year to the 2019–20 course. We have developed a replicable method that permits the bulk of the labour preparing and extracting data for a reading list analysis to transfer from a human to a computer. Others have commented on the need for empirical analysis of reading lists to become more accessible and ways to engage STEM disciplines in curricula decolonisation and we propose that this method has the potential to contribute to both. The results can be offered to subject experts to meaningfully interpret as part of wider decolonisation reflection process and should never be considered in isolation. A high score in CSI metric is not necessarily indicative of a biased curriculum, just as a low score should not be taken as evidence of a diverse, inclusive, or ‘decolonised’ curriculum.

Data availability

All data is available at: https://osf.io/cyj2x/ and in the Supplementary Information.

Code availability

Code is available at: https://osf.io/cyj2x/.

References

Adina, C., Gabriela, C., & Roxana-Denisa, S. (2015). Country-of-origin effects on perceived brand positioning. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 422–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00383-4

Arday, J. (2020). Fighting the tide: Understanding the difficulties facing black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) doctoral students’ pursuing a career in Academia. Educational Philosophy and Theory. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777640

Atanassova, I., Bertin, M., & Mayr, P. (2019). Editorial: Mining Scientific Papers: NLP-enhanced Bibliometrics. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 4, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2019.00002

Bhambra, G. K. (2017). Brexit, Trump, and ‘methodological whiteness’: On the misrecognition of race and class: Brexit, Trump, and ‘methodological whiteness.’ The British Journal of Sociology, 68, S214–S232. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12317

Bilkey, W. J., & Nes, E. (1982). Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations. Journal of International Business Studies, 13(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490539

Cash-Gibson, L., Rojas-Gualdrón, D. F., Pericàs, J. M., & Benach, J. (2018). Inequalities in global health inequalities research: A 50-year bibliometric analysis (1966–2015). PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0191901. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191901

Chakrabarty, D. (2000). Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference. Princeton University Press.

Charles, E. (2019). Decolonizing the curriculum. Insights, 32(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.475

Coimbra, B. de S. S. (2007). Cognitive justice in a global world: Prudent knowledges for a decent life. Lexington Books.

Collyer, F. M. (2018). Global patterns in the publishing of academic knowledge: global North, global South. Current Sociology, 66(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116680020

Chumani Maxwele ignites the #RhodesMustFall Movement at UCT. (2015). [Text]. South African History Online. https://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/chumani-maxwele-ignites-rhodesmustfall-movement-uct

de Oliveira Andreotti, V., & de O., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization Indigeneity, Education & Society, 4(1), 21–40.

Decolonise UCL. (2018) Students’ Union UCL. Retrieved 9 November 2018, from http://studentsunionucl.org/node/115789

Demeter, M. (2019). The world-systemic dynamics of knowledge production: The distribution of transnational academic capital in the social sciences. Journal of World-Systems Research, 25(1), 111–144. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2019.887

Dialogue begins as community confronts, celebrates and learns from past | Imperial News | Imperial College London. (2021). Imperial News. Retrieved 1 November 2021, from https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/231374/dialogue-begins-community-confronts-celebrates-learns/

English Faculty begins decolonisation discussion. (2017). The Cambridge Student. https://www.tcs.cam.ac.uk/news/0037798-english-faculty-begins-decolonisation-discussion.html

Gálvez, A., Maqueda, M., Martínez-Bueno, M., & Valdivia, E. (2000). Scientific publication trends and the developing World: What can the volume and authorship of scientific articles tell us about scientific progress in various regions? American Scientist, 88(6), 526–533.

Gishen, F., & Lokugamage, A. (2018). Diversifying and decolonising the medical curriculum—The BMJ. Retrieved 14 March 2019, from https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/10/18/diversifying-and-decolonising-the-medical-curriculum/

GNI per capita (2019). Atlas method (current US$) | Data. (n.d.). Retrieved 30 January 2019, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD

Grewal, M. (2021). To ‘decolonise’ education, we need to ask different questions. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/opinion/decolonise-education-we-need-ask-different-questions

Harris, J. K., Croston, M. A., Hutti, E. T., & Eyler, A. A. (2020). Diversify the syllabi: Underrepresentation of female authors in college course readings. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0239012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239012

Harris, M., Macinko, J., Jimenez, G., & Mullachery, P. (2017a). Measuring the bias against low-income country research: An implicit association test. Globalization and Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0304-y

Harris, M., Marti, J., Watt, H., Bhatti, Y., Macinko, J., & Darzi, A. W. (2017b). Explicit bias toward high-income-country research: a randomized, blinded, crossover experiment of english clinicians. Health Affairs, 36(11), 1997–2004. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0773

Harris, M., Weisberger, E., Silver, D., Dadwal, V., & Macinko, J. (2016). That’s not how the learning works – the paradox of Reverse Innovation: A qualitative study. Globalization and Health, 12(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0175-7

Harris, M., Weisberger, E., Silver, D., & Macinko, J. (2015). ‘They hear “Africa” and they think that there can’t be any good services’ – perceived context in cross-national learning: A qualitative study of the barriers to Reverse Innovation. Globalization and Health, 11(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-015-0130-z

Issa, H., Kulasabanathan, K., Darzi, A., & Harris, M. (2017). Shared learning in an interconnected world: The role of international health partnerships. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 110(8), 316–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076817712251

Keiser, J., Utzinger, J., Tanner, M., & Singer, B. H. (2004). Representation of authors and editors from countries with different human development indexes in the leading literature on tropical medicine: Survey of current evidence. BMJ, 328(7450), 1229–1232. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38069.518137.F6

Khokhar, T., & Serajuddin, U. (2015). https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/should-we-continue-use-term-developing-world. World Bank Blogs.

Kubota, R. (2020). Confronting epistemological racism, decolonizing scholarly knowledge: Race and gender in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 41(5), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz033

Kulasabanathan, K., Issa, H., Bhatti, Y., Prime, M., del Castillo, J., Darzi, A., & Harris, M. (2017). Do International Health Partnerships contribute to reverse innovation? A mixed methods study of THET-supported partnerships in the UK. Globalization and Health, 13(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0248-2

Leganto Reading Lists (2020). Imperial College London. Retrieved 9 September 2020, from http://www.imperial.ac.uk/admin-services/library/learning-support/reading-lists/

McConnell, C. (2011, August 25). Use ANCIL in your institution. A New Curriculum for Information Literacy. https://newcurriculum.wordpress.com/using-ancil/

Olopade, D. (2014). Opinion | The End of the ‘Developing World’. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/01/opinion/sunday/forget-developing-fat-nations-must-go-lean.html

Open Syllabus. (2020). https://opensyllabus.org/

Pan, R. K., Kaski, K., & Fortunato, S. (2012). World citation and collaboration networks: Uncovering the role of geography in science. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00902

Phull, K., Ciflikli, G., & Meibauer, G. (2019). Gender and bias in the international relations curriculum: Insights from reading lists. European Journal of International Relations, 25(2), 383–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066118791690

#RHODESMUSTFALL. (2018). #RHODESMUSTFALL. Retrieved 12 December 2018, from https://rmfoxford.wordpress.com/

Salager-Meyer, F. (2008). Scientific publishing in developing countries: Challenges for the future. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 7(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2008.03.009

Schucan Bird, K., & Pitman, L. (2019). How diverse is your reading list? Exploring issues of representation and decolonisation in the UK. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00446-9

Shahjahan, R. A., Estera, A. L., Surla, K. L., & Edwards, K. T. (2021). “Decolonizing” curriculum and pedagogy: A comparative review across disciplines and global higher education contexts. Review of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211042423

Skopec, M., Fyfe, M., Issa, H., Ippolito, K., Anderson, M., & Harris, M. (2021). Decolonization in a higher education STEMM institution – is ‘epistemic fragility’ a barrier?. London Review of Education. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.19.1.18

Skopec, M., Grillo, A., Kureshi, A., Bhatti, Y., & Harris, M. (2021b). Double standards in healthcare innovations: The case of mosquito net mesh for hernia repair. BMJ Innovations, 7(2), 482–490. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2020-000535

Skopec, M., Issa, H., & Harris, M. (2019). Delivering cost effective healthcare through reverse innovation. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6205

Srinivasan, N., Jain, S. C., & Sikand, K. (2004). An experimental study of two dimensions of country-of-origin (manufacturing country and branding country) using intrinsic and extrinsic cues. International Business Review, 13(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2003.05.004

Sumner, J. L. (2018). The gender balance assessment tool (GBAT): A Web-based tool for estimating gender balance in syllabi and bibliographies. PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(2), 396–400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517002074

Taylor, M., Hung, J., Che, T. E., Akinbosede, D., Petherick, K. J., & Pranjol, M. Z. I. (2021). Laying the groundwork to investigate diversity of life sciences reading lists in higher education and its link to awarding gaps. Education Sciences, 11(7), 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070359

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

UCL. (2014). Why is my curriculum white? - UCL - Dismantling the Master’s House. Retrieved 1 May 2020, from http://www.dtmh.ucl.ac.uk/videos/curriculum-white/

University of Westminster. (2020). Decolonising the curriculum toolkit. Retrieved 1 January 2020, from http://cti.westminster.ac.uk/decolonising-the-curriculum-toolkit/

Verlegh, P. W. J., & Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. (1999). A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20(5), 521–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(99)00023-9

Web of Science Core Collection. (2020). Web of Science Group. Retrieved 9 October 2020, from https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science-core-collection/

Wilson, K. (2019). Decolonising LSE Collective. Decolonising Library Collections: Towards Inclusive Collections Policies. https://decolonisinglse.wordpress.com/2019/10/26/decolonising-library-collections-towards-inclusive-collections-policies/

Acknowledgements

The project was funded by an Imperial College London Presidents Excellence grant for Innovation in Teaching and Learning. MH is supported in part by the NW London NIHR Applied Research Collaboration. Imperial College London is grateful for support from the NW London NIHR Applied Research Collaboration and the Imperial NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding

Funded by Imperial College London Presidents Excellence grant for Innovation in Teaching and Learning.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: all authors; Methodology: Robyn Price, Mark Skopec, Matthew Harris and Simon Mackenzie; Software: Simon Mackenzie and Gemma Seabrook; Formal analysis and investigation: Mark Skopec; Writing—original draft preparation: Robyn Price and Mark Skopec; Writing—review and editing Robyn Price, Mark Skopec, Coco Nijhoff and Matthew Harris; Funding Acquisition: Matthew Harris; Supervision: Ruth Harrison and Matthew Harris.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Price, R., Skopec, M., Mackenzie, S. et al. A novel data solution to inform curriculum decolonisation: the case of the Imperial College London Masters of Public Health. Scientometrics 127, 1021–1037 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04231-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04231-3