Abstract

Previous research has expressed concerns about firms engaging less in basic research. We contribute to this debate by studying trends in the scientific publishing activities of firms located in Germany. Our results indicate that the firms’ aggregate volume of scientific publications stayed constant between 2008 and 2016. However, the number and share of publishing firms declined, and publication activities became more concentrated among publishing firms. Beyond that, we observe positive trends in publishing in basic research journals compared to journals focused on applied research, and publishing in collaboration with academic partners compared to publishing alone. Thus, our results paint an ambiguous picture. While they do not confirm a decrease in firms’ basic research engagement in the aggregate, the figures document a concentration of publishing activities on fewer firms. We argue that this concentration of basic research activities in firms may pose a threat to the longer-term innovativeness of the German economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Firms make important contributions to scientific knowledge. However, there are concerns that firms’ contributions to scientific progress are diminishing. Recent studies report a downward trend in scientific publications co-authored by firm-affiliated researchers (Arora et al., 2018; Larivière et al., 2018; Tijssen, 2004). The proportion of firm publications in scientific output significantly declined over the last decades (Larivière et al., 2018). Arora et al. (2018) find that large US firms grew less likely to publish since the 1980s, and conclude that large firms are withdrawing from basic research. At the same time, other studies, which use alternative methodologies and examine other countries (Archambault & Larivière, 2011; Chang, 2014; Sun et al., 2007) or samples of firms (Camerani et al., 2018; Simeth & Cincera, 2016; Simeth & Raffo, 2013), show a rise in firms’ publication activities. Thus, there seems considerable ambiguity in current trends, which requires deeper analysis.

By matching Scopus to the Mannheim Enterprise Panel, we provide detailed results on the population of scientific publications originating from firms located in Germany for the years 2008–2016. First, we document that, while the aggregate number of scientific publications by firms in Germany has stayed constant over this period, the overall number of publishing firms has declined, as has their share in the population of German firms. At the same time, publication activities have grown more unequally distributed among publishing firms. Second, we analyse the nature of publications by firms in Germany, and show that they have been increasingly published in journals focusing on basic research, as opposed to applied research. Moreover, we find that an increasing number of firm publications has been published in collaboration with German research institutes or universities. Overall, our findings thus paint a nuanced picture. While the aggregate scientific contributions of firms in Germany has remained stable, publication activities are concentrating on fewer firms, and rely more on collaboration with public science.

The contribution of our paper is threefold. First, our generated dataset allows the analysis of the publication activities of the population of German firms, avoiding a sample bias inherent to most other studies that start from a selected subsample of firms. Second, we update the analyses of trends in firm publishing to the period 2008 to 2016 and are thus more recent than existing studies. Third, we compare directly the overall publication trends of frequently used subsamples of firms, such as large firms and innovation active firms. We also provide detailed insights by sector.

Literature review

In its seminal treatment of incentives for science, Nelson (1959) claimed that basic research needs to be funded by the state because knowledge, as a public good, is subject to spillovers. Firms will therefore underinvest in basic science because they are unable to appropriate the full returns associated with the knowledge they create. Nonetheless, empirical evidence shows that firms are active in publishing nonetheless, which seems to contradict this simple wisdom. Many scholars have therefore provided additional reasons, which can explain why firms rationally invest in basic science and become active publishers. The literature on firm publishing reveals five broad, and to some extent interrelated, motives for publishing (see Camerani et al., 2018 for a review): to stay involved with the scientific community, to attract and retain scientists for their research departments, to signal stakeholders and investors, to complement other forms of intellectual property, and to support the commercialisation of new products.

Because firm publications mirror a sort of high-end knowledge, it is believed that they mirror a firm’s competitive edge in high-tech or knowledge-intensive fields, which are typically also more disruptive. Because of this, an increasing number of scholars have analysed trends in firms’ publishing behaviour. However, evidence is mixed on the question whether firm publishing is increasing or decreasing. Camerani et al. (2018) show that the number of publications by the 2500 most R&D active firms worldwide grew by 2.3% per year between 2011 and 2015. Studies of firm publications in Canada (Archambault & Larivière, 2011), Japan (Sun et al., 2007), and Taiwan (Chang, 2014) also document that their number is increasing. This is also found in analyses of innovative French firms (Simeth & Raffo, 2013), large international firms listed in Compustat (Simeth & Cincera, 2016), and other samples of firms (e.g. Godin, 1996; Halperin & Chakrabarti, 1987). Others have documented increasing numbers of firm publications in the pharmaceutical and electronics industries (Hicks et al., 1996; Narin & Rozek, 1988), in the semiconductors industry (Pellens & Della Malva, 2018), and in the field of artificial intelligence (Hartmann & Henkel, 2020).

Other studies conclude that the number of firm publications decreases. Tijssen (2004) shows that the number of worldwide firm publications between 1996 and 2001 declined by 12%, starkly contrasting increases in the number of industrial researchers and patent applications. Studying large pharmaceutical firms, Rafols et al. (2014) finds a drop of 9% in the period between 1995 and 2009. The authors interpret this as a general reduction of effort in traditional core research fields, rather focusing more on health services and clinical research, and an increased reliance on external research partners for basic research. In a case study of publishing at IBM, Bhaskarabhatla and Hegde (2014) show that IBM’s publications dropped from 1989 onwards. However, this was the result of changing incentives schemes for inventors, and not necessarily indicative of a broader trend.

Some of the differences in the findings are clearly due to different methodological approaches and databases. Despite this ambiguity in the overall numbers, it is clearer that the share of firm publications among the whole body of scientific output is decreasing. Camerani et al. (2018) find that the number of publications by top R&D spenders grew less quickly than the number of publications in other institutions. Larivière et al. (2018) document that the proportion of worldwide industry-authored papers more than halved between 1980 and 2014. Thus, in relative terms the importance of firm publications is decreasing.

Relatedly, some studies show that firms become less likely to publish research results, keeping other factors equal. While a decrease in the total number of scientific publications by firms could be primarily driven by a drop in the aggregate level of R&D investment, these analyses show that also the number of corporate publications has decreased even when R&D investments are factored in. Conditional on other firm characteristics, among which R&D expenditures, Arora et al. (2018) find firms on average generate 20% fewer publications per decade between 1980 and 2006, and Arora et al. (2021) report a decline of 44% between 1980 and 2015. Arora et al., (2018, 2021) interpret these shifts as a decreasing engagement in scientific research. This trend seems to be heterogeneous across and within sectors. In the semiconductor industry, for instance, Pellens and Della Malva (2018) estimate that fabless firm’s propensity to publish grows by 4% yearly, whereas that of manufacturing firms remains constant.

In total, even though firms are in aggregate publishing large quantities of scientific publications, the number of publications per unit of R&D expenditures is dropping. This indicates that firms are contributing a smaller proportion of the knowledge they generate to the scientific literature (Arora et al., 2018, 2021; Larivière et al., 2018; Tijssen, 2004). Arora et al. (2018) argue this trend is driven by a decline in the private value of science or by an increase in the cost of doing research. In fact, the latter idea is in line with the findings of Bloom et al. (2020), who document decreasing returns to R&D in many settings. One possible explanation is that firms are increasingly motivated to keep research findings secret, in order to maintain a knowledge advantage (Larivière et al., 2018). Arora et al. (2018), however, argue that this is unlikely, as they find that firms are especially disconnecting from high-impact science, which they argue contains mostly basic research. If firms increasingly valued the ability to appropriate findings, they should be proportionally less likely to publish commercially valuable applied research findings.

Amid these trends, the manner in which firms are publishing is also changing. Firms are less inclined to publish by themselves or in collaboration with other firms, and publish more in collaboration with scientific institutes (Camerani et al., 2018; Hartmann & Henkel, 2020; Hicks et al., 1996; Larivière et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2007; Tijssen, 2004). These shifts match positive trends in industry-science collaborations in general (Calvert & Patel, 2003; Tijssen, 2012). One interpretation of this changes is that firms shift their priorities, increasingly conducting basic research with external partners and focusing more intensely on applied research and commercialisation (Arora et al., 2018; Pisano, 2010; Rafols et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2007; Tijssen, 2004). An alternative interpretation are increased collaborations which are the result of firms seeking out external knowledge or high-potential recruits in universities (Hicks et al., 1996).

In summary, the evidence on the trend in firm publishing is mixed, and depends on the time period under consideration, the nature of the sample, and the exact outcome measure analysed. What most studies appear to agree on, however, is that the contributions of firms to scientific knowledge are increasingly manifesting in collaboration with scientific institutions.

Data

Data preparation

To analyse the publication activities of German firms, we draw on the Scopus database provided by Elsevier. We further use the Mannheim Enterprise Panel generated by the ZEW Mannheim, and the German Patent Office’s patent database. The three datasets are matched and aggregated at the firm-year level. The final dataset comprises yearly information on firms’ publishing and patenting activities by industry and size. We add aggregate numbers on the population of all German firms from the official Business Register of Germany to our trend analyses.

In using Scopus to identify scientific firm articles, we follow Simeth and Cincera (2016). Scopus is the largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature.Footnote 1 It comprises information on scientific journals, books and conference proceedings. We use the disambiguation of articles, letters, notes, reviews, and conference proceedings from Rimmert et al. (2017) to identify publications published by at least one author affiliated to a German firm. These publications are defined as firm publications and we extract information on their authors’ affiliations, their composition of authors, their citations and type of research. The strategy by Rimmert et al. (2017) has been generated by the Bibliometric Group of the University Bielefeld since 2008 in the context of the German Competence Centre for Bibliometrics and is comprehensively described in Winterhager et al. (2014). They develop a semi-automatic procedure, which detects text patterns in authors’ affiliation information and combines them with additional data on the German science system. The procedure identifies eight classes referring to publications from firms, two different university types, four different kinds of non-university research institutes, departmental research of federal or state ministries, and others.Footnote 2 We access the disambiguation for Scopus via the German Competence Centre for Bibliometrics (Winterhager et al., 2014). We extract 89,849 publications with at least one author affiliated to a firm and published between 2005 and mid-2017.

We enrich this data with information on firms’ industry classes and employment numbers. For this, we draw on the Mannheim Enterprise Panel. This dataset contains the data pool of the largest German credit rating agency—Creditreform e.V.—and is maintained by the ZEW Mannheim since 1992. It includes information on various firm characteristics for approximately 8.8 million running and closed firms located in Germany.Footnote 3 It is the most comprehensive firm-level database in Germany next to the official Business Register of the Federal Statistical Office and provides a representative picture of the German corporate landscape (Bersch et al., 2020). The panel covers around 90% of the entire population of active firms in Germany and is sampling frame for the official German Community Innovation Survey of the European Commission (Bersch et al., 2014). Firms are defined as legally independent enterprises: The smallest legally independent unit, which operates its own accounts due to commerce or tax law reasons. Thus, the dataset covers parent companies and their subsidiaries as individual units. Creditreform updates the dataset and adds new firms on a half-yearly basis. It retrieves its information from (i) different official registers, (ii) print and internet media, (iii) business reports, and (vi) own investigations based on client requests.

To match Scopus records and firm information, we extract affiliation names and addresses from our sample of publications.Footnote 4 We aggregate them to 47,124 unique name-address combinations, whereas many combinations are similar and only have minor differences in their spelling. There are for instance only 22,757 unique names and 11,080 unique city-street combinations. The name-address combinations are matched to the entire Mannheim Enterprise Panel covering the period 1992 to 2017. Name-address combinations are either matched exactly, or, in case the exact affiliation from Scopus was not found in the firm panel, matched to the most similar name-address combination using the ZEW Search Engine. The ZEW Search Engine is a text analysis software developed at ZEW and frequently used to combine the Mannheim Enterprise Panel with other datasets such as the PATSTAT database of the European Patent Office or the public funding database PROFI of the German Ministry of Education and Research (Bersch et al., 2014). The software matches keywords in the name and address information of both datasets, whereas rare words receive a higher weight than frequently used ones.Footnote 5 A more detailed description of its algorithm is provided in Doherr (2017). To avoid mismatches arising from the automated procedure, we also manually check all matches. We match 99.6% of all combinations to 2459 enterprise panel entries. This corresponds to matching 95.8% of all extracted firm publications, whereby each publication was allocated to 1.2 firms on average. Publications are attributed to firms over the generated affiliation-firm match. If a publication has two or more authors from the same or from different German firms, the publication is attributed once to each participating firm.

The patent database stems directly from the German Patent Office and covers the received patent applications from 1896 to 2017 onwards. Inter alia, the database contains information on the names and addresses of patent applicants. The match between the Mannheim Enterprise Panel and the patent database is directly provided by the ZEW Mannheim and also based on its text analysis software (Doherr, 2017). Instead of author affiliations, the matching uses patent applicant names and addresses.

The information from all three datasets is aggregated to the firm-year level. For our analysis, we restrict the sample to publishing firms within industries covered by the European Community Innovation Surveys.Footnote 6 The surveys are used to estimate official statistics on the business enterprise sector’s innovativeness and thus cover the same target population as our examination.Footnote 7 Furthermore, we focus on citable items (see Garfield, 1979; Moed, 2005) and, thus, abstract from conference proceedings. The reason for this is that conference proceedings in many cases only list the presenting author (Michels & Fu, 2014). Therefore, they cannot be attributed to all their authors reliably and, in addition, underestimate joint publications. Finally, we do not consider the pre-economic-crisis years before 2008. Our investigated period therefore covers the years 2008 to 2016. After applying these three restrictions, our panel represents 1647 firms that publish 43,063 firm publications in full counts. We use full counts at the firm-level for our analysis, as our paper focuses on the participation of firms in scientific publishing. Full counting and fractional counting methods create information from different perspectives. Full counting provides information from the perspective of participation, whereas fractional counting provides information in terms of contribution (Moed, 2005). The reason for this is that fractional counting assigns less weight to the collaborative publications of a firm, whereas full counting assigns the same weight to each publication. Fractional counting is therefore particularly suitable to measure the contribution of German firms to the entirety of scientific German publications. However, full counting is more suitable for our analysis of the participation of German firms in scientific publishing and its development.

Variable construction

Publication volume

The yearly publication volume of a firm is calculated as the sum of the yearly published articles, letters, notes, and reviews from authors affiliated to the firm as marked by our matching procedure of Scopus and the Mannheim Enterprise Panel.

Applied and basic research publications

The yearly publication volume of each firm is classified into basic and applied research publications. We use the journal-level classification of Boyack et al. (2013) differentiating between (i) applied science, (ii) art and humanities, (iii) general, (iv) economic and social sciences, (v) natural sciences and (vi) health sciences. The classification is based on an automatic identification of keywords related to the different classes within the abstracts and titles of publications in a journal. We define publications in journals of the first category “applied science” as applied research and all publications of the remaining five categories as basic research. 18% of the aggregate firm publication volume cannot be classified into applied or basic research as their journal is not classified.

Publications with domestic co-author groups

We use the disambiguation of Rimmert et al. (2017) to identify the publications of firms that are co-authored with German academia and other German firms. German academia is defined as all identified university and non-university institute types. 32% of the aggregate firm publication volume cannot be attributed as these publications also include other affiliations than German academia or firms. We limit our co-author composition classes to domestic collaboration, as we cannot reliably distinguish between co-authors from academia, firms or other organizations for other countries than Germany.

Highly cited publications

Highly cited publications refer to the 10% of mostly cited publications worldwide (Waltman & Schreiber, 2013). To avoid field differences and time trends, we follow Schmoch et al. (2016) and identify highly cited publications separately for each year and Scopus science fields.

Firm characteristics

We define firms with more and equal to 500 employees as large. The information is directly taken from the Mannheim Enterprise Panel. Firms with one or more patent application at the German Patent Office according to the provided matching are defined as patenting firms.

Firm population

The yearly number of active firms in Germany within our target industries are extracted from the aggregate numbers of the official German Business Register. We differentiate between the entire population of firms, large firms, firms in different high-tech manufacturing industries and firms in different knowledge-intensive service industries.

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics on our constructed balanced firm-year panel dataset, and shortly describes the different variables, which are used to examine aggregate trend statistics in the following section. Table 2 displays descriptive statistics on firms’ publication volume for different industry subsamples. Technical details about the sample and short descriptions on the variables’ generation are included as notes below the tables and figures. For all publication variables, our main analysis focuses on whole counts.

Table 1 shows that the average yearly publication volume of a firm which published at least once within 2008 and 2016 is 2.92 on average, whereas the largest observed yearly publication volume accounts to 337 publications. Moreover, the average yearly publication volume in basic research journals of 1.66 is more than twice as high as the average yearly publication volume in applied research journals of 0.74. In addition, firms publish more in cooperation with German academia than alone or with other German firms, or with both. The average publication volume of highly cited publications is 0.59 and thus makes around 20% of a firm’s entire publication volume. 57% of the sample applied at least once for a patent at the German patent office and around a third, 29%, employs 500 persons or more.

Table 2 describes the publication volumes of publishing firms per industry. It shows that the average publishing firm in technology-intensive manufacturing and knowledge-intensive services produces a higher number of publications than firms in less technology- and knowledge-intensive industries. Firms in high-tech manufacturing publish on average the most with 5.51 publications per year. Firms in medium-high-tech manufacturing are ranked second with on average 4.33 publications per year. In medium-low- and low-tech manufacturing, publishing firms show a much lower publication volume of 0.86 and 0.74 publications per year. Publication volumes are higher again among firms in knowledge-intense service industries. While not reaching the level of high-tech and medium-high-tech manufacturing, they publish between 2.42 and 2.84 publications per year. Publishing firms in other industries produce on average 2.10 publications per year.

Aggregate trends in scientific publishing of German firms

Increasing concentration of corporate publishing

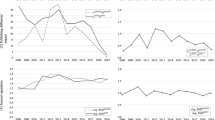

Figure 1 describes aggregate trends in firm publishing. Panel A shows the aggregate publication volume. There is no clear trend in the number of firm publications. With some annual fluctuations, the overall volume of firm publications stays between 4700 and 5000, with a slight dip to 4315 during the financial crisis in 2009 and 2010. However, the figures return quickly to the pre-crisis level afterwards. This general trend is also present when only considering large or patenting firms. Panel B displays the evolution of the number of publishing firms. Despite a rather constant absolute number of publications, the core of publishing firms has shrunk. While the overall number of publishing firms was above 700 in 2008, the number decreased to around 600 in 2016. Thus, while the overall number of publications did not shrink, they originated from fewer firms, which on their side increased their publication activities. This is reflected in panel C, which shows that the average number of publications per publishing firm has increased between 2008 and 2016.

Trends in the activities of publishing firms. Large firms are defined as firms with >= 500 employees. Patenting firms are defined as firms, which applied for a patent at the German patent office at some point in time. Panel A: The yearly publication volume is calculated by summing up the publication volumes over all firms within a given year. Publications authored by several firms are thus counted once for each firm. Panel B: The yearly number of publishing firms is calculated by counting the amount of firms with a publication volume of at least one in a given year. Panel C: The yearly average number of publications per publishing firm corresponds to the aggregate publication volume from panel A divided by the number of publishing firms from panel B

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the average number of publications per publishing firm by high-tech manufacturing industries in Panel A and of knowledge-intense service industries in Panel B. It demonstrates an increase in the average number of publications for high-tech and medium-high-tech manufacturing, whereas it remained stable among the other industries. Thus, the trend observed for the aggregate data in Fig. 1 is driven by changes in high-tech and medium-high-tech manufacturing. Figure 6 in the Appendix displays the evolution of the aggregate publication volume and the number of publishing firms for each industry. The figure shows that the aggregate number of publications has remained relatively stagnant among high-tech manufacturing firms, while the number of publishing firms has decreased. In medium-high-tech manufacturing, the number of publications has increased while the number of publishing firms has gone down.

Trends in the number of publications per publishing firm, by industry. See Fig. 6 in the Appendix for aggregate publication volumes and the number of publishing firms by industry. The industry classification displayed follows the definition of high-tech manufacturing industries and knowledge-intensive service industries by Eurostat (2016). Each line represents the aggregate publication volume in the industry divided by the number of publishing firms in the industry

The above analysis documents that publication activities, while relatively stable in the aggregate, are concentrating on a smaller number of firms. To confirm that these observations are not driven by changes in the composition of German industries, Table 3 shows the evolution of the share of publishing firms among the population of German firms. The population of German firms has remained roughly stable between 2008 and 2016. However, the average share of publishing firms has decreased by approximately 11%. Whereas in 2008–2010 on average 3.37 firms published per thousand firms, this was only the case for 2.99 firms per thousand in 2014–2016. Moreover, the average number of publications per firm in the population has increased from 0.23 publications per 100 firms in 2008–2010 to 0.25 publications in 2014–2016. The population of larger firms has grown with approximately 13% over the study period. The number of large firms increased from on average 3796 firms in 2008–2010 to on average 4286 firms in 2014–2016. At the same time, the share of publishing firms has decreased by approximately 24%, from 6.93% of large firms in 2008–2010 to 5.28% in 2014 to 2016. Meanwhile, the average number of publications among large firms has also decreased with approximately 5% from 0.80 publications per firm in 2008–2010 to 0.76 in 2014–2016. Therefore, not only the number of publishing German firms has decreased between 2008 and 2016, but also the share of publishing firms among the entire firm population and among the population of large firms.Footnote 8 At the same time, the average number of publications per firm has increased in the full population and decreased in the population of large firms.

Table 4 breaks down the same numbers by industry. It shows that the populations of firms in high-tech and medium-high-tech industries have experienced a decline over the study period. This is combined with an initial rise in the shares of publishing firms within both industries from 2008–2010 to 2011–2013, and a subsequent drop in 2014–2016. Overall, the share of publishing firms in high-tech and medium-high-tech industries remained rather constant over the study period, with differences of respectively 1 and 2 percentage points between 2008–2010 and 2014–2016. Between 2014 and 2016, the share of publishing firms was on average 0.70% in high-tech manufacturing and 0.30% in medium-high-tech manufacturing. At the same time, numbers of publications per firm grew in both industries. In high-tech industries, the average number of publications per firm grew from 7.69 publications per 100 firms to 9.35, a relative increase of approximately 22%, and in medium-high-tech industries, it grew from 3.03 to 4.17, a relative increase of approximately 38%. Thus, while the share of German firms that publish decreased overall, this is not the case in high-tech and medium-high-tech manufacturing, the industries generating most corporate publications, along with knowledge-intensive high-tech and knowledge-intensive market services.

As an additional measure for the concentration of publishing activities, we calculated Gini coefficients for the distribution of publications. Considering the very small share of publishing firms, we focus on the distribution of publications among publishing firms. Thus, whereas Table 4 considers changes in the extensive margin of publication activities, Table 5 considers its intensive margin. The table shows that the distribution of corporate publications among publishing firms, despite being very unequal from the beginning, has grown more unequal between 2008–2010 and 2014–2016: The Gini coefficient increased from 0.69 to 0.72 for the population of all publishing firms, and from 0.72 to 0.74 for publishing large firms and patenting firms. Table 6 displays the Gini coefficients for different industries. For all industries except medium-low-tech manufacturing the Gini coefficient has increased over the study period. Moreover, the distribution of publications is most concentrated in high-tech and medium-high-tech manufacturing.

The previous analysis has revealed trends in corporate publishing in Germany. While the aggregate volume of scientific publications with authors affiliated to firms in Germany has remained constant, corporate publication activities have become more concentrated. First, the overall share of publishing firms in Germany has decreased. However, the trend is less clear for the share of publishing firms in high-tech and medium-high-tech manufacturing industries. Second, the distribution of corporate publishing has grown more concentrated among publishing firms in all industries except medium-low-tech manufacturing.

These findings match previous findings by Rammer and Schubert (2018), who showed that the innovation activities in Germany, although on the rise, are driven by a declining core of innovation active firms—a trend that started already in the early 2000s. Our results further complement recent studies concluding that firms contribute less of their research outputs to science (Arora et al., 2018, 2021) and that corporate science accounts for a smaller share of total science (Larivière et al., 2018), even though publication volumes are still growing among top R&D spenders (Camerani et al., 2018). Compared to these studies, we confirm shifts in the publication activities of firms in Germany: Whereas the volume of firm publications has remained stable, publications are concentrating on a smaller set of firms. In what follows, we further investigate trends in the nature of published corporate science, and its impact.

Increasing ratio of basic research publications

Figure 3 shows that the ratio of basic to applied research publications by German firms has grown from 1.7 in 2008 to 2.6 in 2016. Hence, while there is a general stagnation of the overall publication volume as shown in Fig. 1, the amount of basic research publications has risen compared to applied research publications. Thus, in contrast to US firms (Arora et al., 2018), we find that publications by German firms have become more basic over the last 10 years.Footnote 9 One reason for such a relative decline in applied publishing might be that firms are increasingly reluctant to publish commercially relevant information, in order to maximise opportunities for appropriation. Another driver might be related to changes in the composition of firm publishing, where collaborations with universities account for an increasing share of firms’ publications (Camerani et al., 2018; Hartmann & Henkel, 2020; Hicks et al., 1996; Larivière et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2007; Tijssen, 2004). Under the assumption that collaborations with universities are more basic in nature than research conducted solely by firms, an increase in collaborations with universities might explain the trend towards basic research.

Development of the ratio between applied and basic research publications. The ratio equals the aggregate yearly publication volume of all firms in basic research divided by the yearly publication volume of all firms in applied research. 18% of the overall aggregate publication volume cannot be classified into applied or basic research and is not taken into account for the calculation

Joint publications and their impact

Figure 4 shows, in line with prior studies (Camerani et al., 2018; Hartmann & Henkel, 2020; Hicks et al., 1996; Larivière et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2007; Tijssen, 2004), that the stagnation in the number of firm publications is driven by, on the one hand, a decrease in the number of publications published only by authors from the same firm, and, on the other hand, an increase of publications including co-authors from academia. Since the number of publications including other firms, as well as other firms and academia stayed about the same in the period between 2008 and 2016, we find that science-industry co-publications were generally growing at the expense of publications not co-authored with any other organization. This pattern is consistent with the increasing share of basic research publications documented in the previous section.

Trends in the aggregate publication volume by domestic cooperation partner. The yearly publication volume by domestic cooperation partner(s) is calculated by separately summing up the different publication volumes over all firms within a given year. Publications authored by several firms are thus counted once for each firm. We limit our cooperation partner classes to domestic cooperation as we cannot reliably distinguish between academia, firms or other organizations for other countries than Germany

These patterns are especially relevant as there is a clear relation between the nature of science collaboration and scientific impact. In Fig. 5, we plot the excellence rate, the share of a firm's publications in the 10% most cited publications by type of co-publication. Consistently, the publications authored only by the focal firm rank lowest with an excellence rate between 12 and 17%. Highest, in particular in the most recent periods, are the publications with academia (20% in 2016) and academia and other firms (19% in 2016). Similar trends can also be observed when using the citation rate—the number of citations per publication—as a benchmark. Here too, co-publications with academic involvement rank highest as also demonstrated in previous studies (Pohl, 2021).

Trends in the aggregate shares of highly cited publications by domestic cooperation partner. (1) The yearly publication volume of highly cited publications is allocated to the four domestic co-author groups for each firm individually. The allocation is proportional to a co-author group’s share on a firm’s yearly overall publication volume. (2) The yearly publication volume of highly cited publications by domestic co-author group is calculated by separately summing up the different allocated publication volumes over all firms within a given year. (3) The yearly overall publication volume by domestic co-author group is calculated by separately summing up the publication volumes over all firms within a given year. (4) The yearly share of highly cited publications by domestic co-author group is calculated by dividing the yearly publication volume of highly cited publications by the overall publication volume. Normal and highly-cited publications authored by several firms are counted once for each firm. We limit our collaboration partner classes to domestic cooperation as we cannot reliably distinguish between academia, firms or other organizations for other countries than Germany

Conclusion

Our comprehensive analysis of the scientific publications of German firms adds to the still limited body of literature on the development of firm publications. Our results indicate that German firms, in aggregate, are not publishing significantly less in scientific literature over the last decade. At the same time, firm publishing is concentrating on a smaller set of firms. This pattern mirrors a more general concentration of innovation activities in Germany revealed by Rammer and Schubert (2018). This trend is accompanied by a tendency towards publishing in journals focusing on basic research, and in co-authorship with German scientific institutes.

An important implication of our finding is that we are unable to subscribe to a simple “yes” or “no” on the question of whether firms are withdrawing from science. On the one hand, our results indicate that the total number of publications remains relatively stable, implying limited reason for concern. In addition, the observation that publications’ degree of basicness is increasing indicates that, overall, firms do not appear to leave basic research. On the other hand, the number and share of publishing firms is decreasing, and the distribution of publishing activities became more concentrated among publishing firms. This concentration on fewer firms indicates that some firms leave scientific research, which may be worrisome and pose a threat on Germany’s future innovativeness. Likewise, the fact that scientific publishing is occurring to a higher degree in collaboration with academia indicates that scientific, and in particular basic, research increasingly requires a division of labour (Arora et al., 2018; Pisano, 2010; Rafols et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2007; Tijssen, 2004).

Our results contribute to a better understanding of the evolution of corporate publishing. Prior evidence was mixed, and came to different conclusions based on different perspectives and frameworks. Our results, first, complement studies of the aggregate volume of publications by firms. Our research is the closest to studies of particular countries, that have documented increasing volumes of corporate publications in Canada (Archambault & Larivière, 2011), Japan (Sun et al., 2007) and Taiwan (Chang, 2014). More generally, Camerani et al. (2018) shows a growing trend in publications by top R&D spenders. We complement these studies with the finding that the aggregate volume of corporate publications has remained stagnant in Germany. We also complement previous studies of particular high-tech industries (Hartmann & Henkel, 2020; Hicks et al., 1996; Narin & Rozek, 1988; Pellens & Della Malva, 2018) with the finding that publication volumes have grown in medium-high tech manufacturing industries. Our results contrast studies that document decreasing volumes of firm publications, in general (Tijssen, 2004) or in the pharmaceutical industry (Rafols et al. 2014). While our analysis cannot speak directly to the importance of corporate publications within the entire scientific corpus of Germany, where previous analyses have shown negative trends (Camerani et al., 2018; Larivière et al., 2018), our analysis shows that corporate publications in Germany are being developed to a smaller degree by firms alone. Compared to the literature showing that firms have become less likely to publish research results (Arora et al., 2018, 2021), our analysis points at a decreasing overall share of firms engaging in publication activities, and an increasing concentration of publications among publishing firms.

We have to acknowledge the following data limitations. First, our results are restricted to the publications collected by the Scopus database. In recent years, new publication outlets, like ArXiv, are gaining relevance in new areas, like Artificial Intelligence. Moreover, we abstract from conference proceedings, because they cannot be reliably attributed in case of multiple authorship. However, in particular in the fields of informatics and electrical engineering, conference proceedings play a vital role for science communication (Michels & Fu, 2014). Incorporating conference proceedings and alternative information would lead to a more complete picture of firm publishing, but is outside the scope of this analysis. Second, some researchers employed by industry are also affiliated with scientific institutes (Yegros-Yegros & Tijssen, 2014) and might only use this affiliation for their publication activities. We are not able to identify these firm publications. Finally, when focusing on joint publications with other firms or academia, we can only identify German organizations and are bound to an analysis of domestic collaborations.

We are aware that our results only present descriptive statistics, which reflect aggregate patterns in firm publishing. They do not capture causal relationships, nor do they take into account changes in underlying factors, such as R&D expenditures. As such, our analysis does not make a statement on the economic impact of the developments in firms’ publication activities for the publishing firms themselves, the German innovation system, or the German economy as a whole.

These limitations provide ground for future research. For one, future research should consider how shifts in firms’ publication behaviour affect innovation and long-term economic performance. While these topics have been considered before (e.g. Arora et al. 2018, Simeth & Cincera, 2016), little attention has been paid to those firms that stop engaging with scientific publishing. Moreover, considering the way in which firms’ different motives for publishing, for instance the aim of engaging with the scientific community compared to supporting the intellectual property strategy, interact with economic outcomes would be valuable. Understanding these relationships is key for the derivation of managerial implications for firms, which might be put for example in the context of open innovation, or intellectual property right management.

Notes

For a comparison between the coverage of Scopus and Web of Science in Germany see Schmoch et al. (2012).

The eight classes are: i. firms, ii. universities of applied sciences, iii. (technical) full universities, iv. Leibniz institutes, v. Fraunhofer institutes, v. Max-Planck institutes, vi. Helmholtz institutes, vii. departmental research of federal or state ministries, and viii. others (e.g. private research institutes and hospitals).

Complete address, phone number, number of employed persons, amount of sales, legal form, industry classification, date of foundation and closure, shareholder structure, credit score, balance sheet data, and insolvency procedures. (Bersch et al., 2014).

The extraction is based on the AFID of Scopus.

As a result, we do not need to further normalize our original 47,124 name-address combinations. Frequently used words, which often minorly differ in their spelling, receive a low weight in the matching process.

The current European Community Innovation Surveys cover the sections B, C, D, E, H, J and K, the divisions 46, 69 to 74 (without the group 70.1) as well as the divisions 78 to 82 of the Nace Rev. 2 Classification (see Eurostat, 2008).

The Community Innovation Surveys follow the OECD’s Oslo Manual and abstract from firms, which are part of industries not or barely related to the business enterprise sector. Example industries are the sections T—Households, U—Extraterritorial bodies or S—Membership organisations.

We cannot provide the same analysis for patenting firms, as the aggregate firm numbers of the official business register differentiate between Nace Rev. 2 industry classes and firm size, but not between patenting and non-patenting firms.

Part of the difference between our finding and the conclusion of Arora et al. (2018), who find that firms are particularly decoupling from basic science, might be one of definition: whereas we make use of a journal-level classification to differentiate basic and applied work (see also Lim 2004), the analysis by Arora et al. (2018) considers high-impact journals as basic.

References

Archambault, E., & Larivière, V. (2011). Scientific publications and patenting by companies: A study of the whole population of Canadian firms over 25 years. Science and Public Policy, 38(4), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234211X12924093660192

Arora, A., Belenzon, S., & Patacconi, A. (2018). The decline of science in corporate R&D. Strategic Management Journal, 39(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2693

Arora, A., Belenzon, S., & Sheer, L. (2021). Knowledge spillovers and corporate investment in scientific research. American Economic Review, 111(3), 871–898. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20171742

Bersch, J., Degryse, H., Kick, T., & Stein, I. (2020). The real effects of bank distress: Evidence from bank bailouts in Germany. Journal of Corporate Finance, 60, 101521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.101521

Bersch, J., Gottschalk, S., Müller, B., & Niefert, M. (2014). The Mannheim Enterprise Panel (MUP) and Firm Statistics for Germany. ZEW Discussion Paper 14-104.

Bhaskarabhatla, A., & Hegde, D. (2014). An organizational perspective on patenting and open innovation. Organization Science, 25(6), 1744–1763. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0911

Bloom, N., Jones, C. I., Van Reenen, J., & Webb, M. (2020). Are ideas getting harder to find? American Economic Review, 110(4), 1104–1144. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180338

Boyack, K. W., Klavans, R., Patek, M., Moon, O., & Lyle, H. U. (2013). An indicator of translational capacity of biomedical researchers. In 18th international conference on science and technology indicators.

Calvert, J., & Patel, P. (2003). University-industry research collaborations in the UK: Bibliometric trends. Science and Public Policy, 30(2), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154303781780597

Camerani, R., Rotolo, D., & Grassano, N. (2018). Do firms publish? A multi-sectoral analysis. SPRU Working Paper 2018-21.

Chang, Y. (2014). Exploring scientific articles contributed by industries in Taiwan. Scientometrics, 99(2), 599–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1222-2

Doherr, T. (2017). InventorMobility Index: A method to disambiguate inventor careers. ZEW Discussion Paper 17-018.

Eurostat. (2008). Nace Rev. 2—Statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community. Eurostat Methodologies and Working Papers, European Communities.

Eurostat. (2016). High-tech industry and knowledge-intensive services (htec)—Reference data in EURO SDMX Metadata Structure (ESMS). Retrieved 04/06/2020, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/htec_esms.htm.

Garfield, E. (1979). Citation indexing—Its theory and application in science, technology, and humanities. Wiley.

Godin, B. (1996). Research and the practice of publication in industries. Research Policy, 25(4), 587–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(95)00859-4

Halperin, M. R., & Chakrabarti, A. K. (1987). Firm and industry characteristics influencing publications of scientists in large American companies. R&D Management, 17(3), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.1987.tb00051.x

Hartmann, P., & Henkel, J. (2020). The rise of corporate science in AI: Data as a strategic resource. Academy of Management Discoveries. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2019.0043

Hicks, D. M., Isard, P. A., & Martin, B. R. (1996). A morphology of Japanese and European corporate research networks. Research Policy, 25(3), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(95)00830-6

Larivière, V., Macaluso, B., Mongeon, P., Siler, K., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2018). Vanishing industries and the rising monopoly of universities in published research’. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0202120. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202120

Lim, K. (2004). The relationship between research and innovation in the semiconductor and pharmaceutical industries (1981–1997). Research Policy, 33(2), 287–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2003.08.001

Michels, C., & Fu, J. (2014). Systematic analysis of coverage and usage of conference proceedings in Web of Science. Scientometrics, 100(2), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1309-4

Moed, H. F. (2005). Citation analysis in research evaluation. Springer.

Narin, F., & Rozek, R. P. (1988). Bibliometric analysis of U.S. pharmaceutical industry research performance. Research Policy, 17, 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(88)90039-X

Nelson, R. R. (1959). The simple economics of basic scientific research. Journal of political economy, 67(3), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1086/258177.

Pellens, M., & Della Malva, A. (2018). Corporate science, firm value, and vertical specialization: Evidence from the semiconductor industry. Industrial and Corporate Change, 27(3), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtx040

Pisano, G. P. (2010). The evolution of science-based business: Innovating how we innovate. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(2), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtq013

Pohl, H. (2021). Internationalisation, innovation, and academic-corporate co-publications. Scientometrics, 126, 1329–1358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03799-6

Rafols, I., Hopkins, M. M., Hoekman, J., Siepel, J., O’Hare, A., Perianes-Rodríguez, A., & Nightingale, P. (2014). Big pharma, little science? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 81, 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.06.007

Rammer, C., & Schubert, T. (2018). Concentration on the few: Mechanisms behind a falling Share of innovative firms in Germany. Research Policy, 47(2), 379–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.12.002

Rimmert, C., Schwechheimer, H., & Winterhager, M. (2017). Disambiguation of author addresses in bibliometric databases—Technical report. Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld, Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies of Science (I2SoS).

Schmoch, U., Michels, C., Schulze, N., & Neuhäusler, P. (2012). Performance and structures of the German science system 2011: Germany in an international comparison, China's profile, behaviour of German authors, comparison of the Web of Science and Scopus. Studien zum deutschen Innovationssystem, No. 9-2012, Expertenkommission Forschung und Innovation.

Schmoch, U., Gruber, S., & Frietsch, R. (2016). 5. Indikatorenbericht bibliometrische Indikatoren für den PFI Monitoring Bericht 2016. Fraunhofer-Institut für System-und Innovationsforschung ISI, Karlsruhe.

Simeth, M., & Cincera, M. (2016). Corporate science, innovation, and firm value. Management Science, 62(7), 1970–1981. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2220

Simeth, M., & Raffo, J. D. (2013). What makes companies pursue an open science strategy? Research Policy, 42(9), 1531–1543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.007

Sun, Y., Negishi, M., & Nishizawa, M. (2007). Coauthorship linkages between universities and industry in Japan. Research Evaluation, 16(4), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.3152/095820207X263619

Tijssen, R. J. W. (2004). Is the commercialisation of scientific research affecting the production of public knowledge? Research Policy, 33(5), 709–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2003.11.002

Tijssen, R. J. W. (2012). Co-authored research publications and strategic analysis of public-private collaboration. Research Evaluation, 21(3), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvs013

Waltman, L., & Schreiber, M. (2013). On the calculation of percentile-based bibliometric indicators. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64, 372–379.

Winterhager, M., Schwechheimer, H., & Rimmert, C. (2014). Institutionenkodierung als Grundlage für bibliometrische Indikatoren. Bibliometrie Praxis und Forschung, 3(14).

Yegros-Yegros, A., & Tijssen, R. J. W. (2014). University-industry dual appointments: Global trends and their role in the interaction with industry. In E. Noyons (Ed.), Proceedings of the science and technology indicators conference 2014 Leiden “Context counts: Pathways to master big and little data” (pp. 712–715).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was funded by the German Ministry for Education and Research; grant number: 01PU17008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 6.

Trends in the activities of publishing firms in high-tech manufacturing and knowledge-intense service industries. The industry classification displayed follows the definition of high-tech manufacturing and knowledge-intensive service industries by Eurostat (2016). Panels A, C The yearly publication volume is calculated by summing up the publication volumes over all firms within a given year and industry. Publications authored by several firms are counted once for each firm. Panels B, D The yearly number of publishing firms is calculated by counting the amount of firms with a publication volume of at least one in a given year

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krieger, B., Pellens, M., Blind, K. et al. Are firms withdrawing from basic research? An analysis of firm-level publication behaviour in Germany. Scientometrics 126, 9677–9698 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04147-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04147-y