Abstract

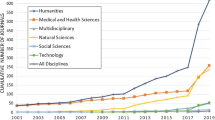

The databases of Web of Science (WoS) have rapidly expanded their coverage of scientific journal during the past few decades. For the providers of WoS, this growth strategy has been a way to reduce existing biases in the coverage of these databases, especially in geographical regard. We look into the consequences of this strategy at the level of disciplines, and discuss its underlying rationales. Our analyses particularly focus on the SSCI. We first highlight interdisciplinary inequalities in the coverage of this database, and discuss why disciplines, such as Economics and Management, which are hierarchically-structured and whose journals have high impact factors in WoS, have benefited most from the growth of WoS. Their relative weight in the SSCI has grown at the expense of other disciplines. We also argue that changes in the coverage of this database have performative effects. There are winners and losers of the editorial expansion strategy of WoS in the real academic world. In the concluding section, we suggest that the providers of WoS reconsider the coverage of their databases in order to reflect and protect the interdisciplinary diversity in the world of science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For details about the composition of the Master Journal List, see https://mjl.clarivate.com/home. Inclusion in the Master Journal List is a precursor to calculating the journal impact factor and rank order.

See https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/journal-evaluation-process-and-selection-criteria/. A similar point of view has driven the development of WoS under its successive owners, viz. the Institute for Scientific Information, Thomson Reuters and now Clarivate Analytics.

Journals are required to consist of peer-reviewed content, to be published without delays or interruptions in the schedule, to have English abstracts and titles and provide references in Roman script, to make the full journal content available online, to have ethical guidelines and publication malpractice statements, and so on. Online submission systems, such as ScholarOne Manuscripts, are promoted by Clarivate, because they are able to automatically generate much of the required information about the “quality criteria.” The “impact criteria” build upon citation analyses conducted at the journal, author, and editorial board level. For recent overviews of the selectivity of WoS, see Aksnes & Sivertsen (2019) and Singh et al. (2021).

We thus take the coverage of different subject categories in 1997 as point of comparison. It could also be useful to compare the number of indexed journals in each WoS category with (estimates of) the total number of journals in each discipline. It should, however, be taken into account that discussions about what is, and what is not, a ‘real’ scientific journal or a ‘real’ scientific publication are age-old (see, e.g., Manten, 1980). No list will be incontestable. Drawing boundaries between scientific and non-scientific publications might be as contestable as identifying the ‘core journals’ in each subject category.

To look at annual changes in the distribution of journals across SSCI categories, we also calculated Gini coefficients. This coefficient is often used to measure income inequality (e.g., Milanovic, 2016). It examines how (un)equal the cumulative proportion of incomes is distributed over the cumulative proportion of households. Its value may range from 0 (total equality) to 1 (total inequality). For the purpose of this study, we equated journals with incomes and subject categories with households. Our results show that, despite WoS’s ambition to correct historical biases and imbalances, the inequality between disciplines or categories has not been reduced. The Gini coefficients range from 0.34 to 0.39 between 1997 and 2019.

The numbers provided by Testa (2011) slightly differ from the ones WoS nowadays provides. WoS adapts its databases all the time, and also makes changes to historical records, even of its Master Journal List (Birkle et al., 2020). Despite such adaptations, however, the dominant historical trends remain the same.

Because there are at present no national and global lists of individuals working in different fields of research who might be able to publish their work in scientific journals, we cannot control for changes in the number of researchers in each field. When such lists would become available, it would be useful to link changes in the number of researchers or authors to changes in the coverage of databases such as WoS.

We were unable to find evidence for changes in WoS’s policy (such as changes in the delineation of “citable items”) that might account for the spike in the years 2007–2009 in this figure; the evidence we have points in the direction of changes in publishers’ actions and strategies.

For journals in Management, for example, the average number of citable items reached a peak of 71 in 2008, but fell back by one third to 47 in 2012. For journals in Economics, this average fell back by one quarter, from 73 in 2008 to 55 in 2010 and 2011. Journals in Sociology and Anthropology have changed less throughout this period, while those in Social Work gradually expanded their average number of articles and reviews.

The journal Sustainability, which is an online, open-access journal, whose publisher (MDPI) requires that authors pay so-called article processing charges, holds the record: 7184 of its articles and reviews are included in the SSCI for 2019. To put this into perspective: this journal now publishes on its own almost as many articles and reviews as, for example, all the 150 journals included in ‘Sociology’ together.

The total number of all items indexed in the SSCI (‘citable’ and ‘non-citable’) has multiplied by a factor of 3 in this period of time (from 144.937 in 1997 to 411.843 in 2019).

In WoS the impact factor of a given journal for the year 2020, for example, is obtained by the following calculation: the number of citations received in 2020 by items published in this journal in 2018–2019 divided by the number of citable items published in the journal in 2018–2019. The asymmetry in this calculation has been noted by a number of scholars, including Hubbard & McVeigh (2011) and Kiesslich, Weineck & Koelblinger (2016). Citations received by all document types—whether considered citable or not—are counted in the numerator, but only the citable items appear in the denominator. WoS thus counts citations for documents which are not taken into account in the denominator. For some editors, including a high number of ‘non-citable items’ might be an easy way to raise the impact factor of their journals. Prompting authors to include citations to recent articles in the same journal is another, well-known strategy (Larivière & Sugimoto, 2019).

The resulting ‘black lists’ are published on Clarivate’s website, see https://help.incites.clarivate.com/incitesLiveJCR/JCRGroup/titleSuppressions.html. The providers of WoS hitherto seem to have directed most of their attention to ‘unexplainable’ increases of self-citations at the journal level (see also Chorus & Waltman, 2016; Szomszor, Pendlebury, & Adams, 2020).

As an anonymous reviewer of this paper added, researchers in some disciplines or subdisciplines may be inclined to reject the assumptions underlying indicators, such as the JIF. They may not only be opposed to any hierarchy of journals, for example, but they may also feel that other types of impact (on teaching or practice, for instance) are more important than research impact. It may hence perhaps not come as a surprise that the providers of WoS have difficulty adequately covering such epistemic cultures.

It might be added that we are here not speaking of a zero-sum situation. There might be limits to the growth of WoS, but the patterns of growth indicate that the expanded coverage of particular subject categories does not (have to) go at the cost of the coverage of other disciplines. The providers of WoS make choices that have consequences. But these consequences deserve more attention than they hitherto receive.

References

Abbott, A. (2001). Chaos of disciplines. University of Chicago Press.

Adams, J. (2012). The rise of research networks. Nature, 490(7420), 335–356.

Aksnes, D. W., & Sivertsen, G. (2019). A criteria-based assessment of the coverage of Scopus and Web of Science. Journal of Data and Information Science, 4(1), 1–21.

Birkle, C., Pendlebury, D. A., Schnell, J., & Adams, J. (2020). Web of Science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(1), 363–376.

Chavarro, D., Rafols, I., & Tang, P. (2018). To what extent is inclusion in the Web of Science an indicator of journal ‘quality’? Research Evaluation, 27(2), 106–118.

Chorus, C., & Waltman, L. (2016). A large-scale analysis of impact factor biased journal self-citations. PLoS ONE, 11(8), e0161021.

De Rijcke, S., Wouters, P. F., Rushforth, A. D., Franssen, T. P., & Hammarfelt, B. (2016). Evaluation practices and effects of indicator use—a literature review. Research Evaluation, 25(2), 161–169.

Fourcade, M. (2009). Economists and societies: Discipline and profession in the United States, Britain, & France, 1890s to 1990s. Princeton University Press.

Fourcade, M., Ollion, E., & Algan, Y. (2015). The superiority of economists. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(1), 89–114.

Garfield, E. (1979). Citation indexing: Its theory and application in science, technology, and humanities. Wiley.

Giménez-Toledo, E., Mañana-Rodríguez, J., Engels, T. C. E., Guns, R., Kulczycki, E., Ochsner, M., Pölönen, J., Sivertsen, G., & Zuccala, A. A. (2019). Taking scholarly books into account, part II: A comparison of 19 European countries in evaluation and funding. Scientometrics, 118(1), 233–251.

Giménez-Toledo, E., Mañana-Rodríguez, J., Engels, T. C. E., Ingwersen, P., Sivertsen, G., Verleysen, F. T., & Zuccala, A. A. (2016). Taking scholarly books into account: Current developments in five European countries. Scientometrics, 107(2), 685–699.

Gingras, Y., & Khelfaoui, M. (2018). Assessing the effect of the United States’“citation advantage” on other countries’ scientific impact as measured in the Web of Science (WoS) database. Scientometrics, 114(2), 517–532.

Hubbard, S. C., & McVeigh, M. E. (2011). Casting a wide net: The journal impact factor numerator. Learned Publishing, 24(2), 133–137.

Kiesslich, T., Weineck, S. B., & Koelblinger, D. (2016). Reasons for Journal Impact Factor changes: Influence of changing source items. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0154199.

Knorr-Cetina, K. (1999). Epistemic cultures: How the sciences make knowledge. Harvard University Press.

Koch, T., & Vanderstraeten, R. (2021). Journal editors facing scientific indexes: Internationalization pressures in the semi-periphery of the world of science. Learned Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1390

Koch, T., Vanderstraeten, R., & Ayala, R. (2021). Making science international. Chilean journals and communities in the world of science. Social Studies of Science, 51(1), 121–138.

Larivière, V., & Sugimoto, C. R., et al. (2019). The journal impact factor: A brief history, critique, and discussion of adverse effects. In W. Glänzel (Ed.), Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators (pp. 3–24). Springer.

Leydesdorff, L., & Wagner, C. (2009). Is the United States losing ground in science? A global perspective on the world science system. Scientometrics, 78(1), 23–36.

Liu, W. (2017). The changing role of non-English papers in scholarly communication: Evidence from Web of Science’s three journal citation indexes. Learned Publishing, 30(2), 115–123.

Manten, A. A. (1980). Publication of scientific information is not identical with communication. Scientometrics, 2(4), 303–308.

Milanovic, B. (2016). Global inequality: A new approach for the Age of Globalization. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228.

Moosa, I. A. (2018). Publish or perish: Perceived benefits versus unintended consequences. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pendlebury, D. A., & Adams, J. (2012). Comments on a critique of the Thomson Reuters journal impact factor. Scientometrics, 92(2), 395–401.

Sīle, L., Guns, R., Sivertsen, G., & Engels, T. C. E. (2017). European databases and repositories for Social Sciences and Humanities Research Output. ECOOM & ENRESSH.

Sïle, L., & Vanderstraeten, R. (2019). Measuring changes in publication patterns in a context of performance-based research funding systems: The case of educational research in the University of Gothenburg (2005–2014). Scientometrics, 118(1), 71–91.

Singh, V. K., Singh, P., Karmakar, M., Leta, J., & Mayr, P. (2021). The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 126(6), 5113–5142.

Szomszor, M., Pendlebury, D. A., & Adams, J. (2020). How much is too much? The difference between research influence and self-citation excess. Scientometrics, 123(2), 1119–1147.

Testa, J. (2011). The globalization of Web of Science: 2005–2010. Available from: http://wokinfo.com/media/pdf/globalwos-essay

Vanderstraeten, R., & Eykens, J. (2018). Communalism and internationalism: Publication norms and structures in international social science. Serendipities, 3(1), 14–28.

Vanderstraeten, R., & Vandermoere, F. (2015). Disciplined by the discipline: A social-epistemic fingerprint of the history of science. Science in Context, 28(2), 195–214.

Vera-Baceta, M., Thelwall, M., & Kousha, K. (2019). Web of Science and Scopus language coverage. Scientometrics, 121(3), 1803–1813.

Zhu, J., & Liu, W. (2020). A tale of two databases: The use of Web of Science and Scopus in academic papers. Scientometrics, 123(1), 321–335.

Zuckerman, H. (2018). The sociology of science and the Garfield effect: Happy accidents, unanticipated developments and unexploited potentials. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 3, Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2018.00020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vanderstraeten, R., Vandermoere, F. Inequalities in the growth of Web of Science. Scientometrics 126, 8635–8651 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04143-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04143-2