Abstract

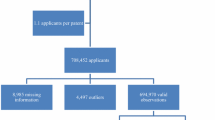

The relationship between basic research intensity and diversified performance is a very important problem that has not theoretically answered. Based on the panel data of universities directly under the ministry of education, considering the three missions of the university and the typical characteristics of basic research, we subdivide the diversified performance into innovation performance, economic performance, social performance and international cooperation performance. We find that enhancing the intensity of basic research can increase the number of patent applications and invention patent applications, but cannot increase the total number of paper publications and the number of English paper publications. Meanwhile, improving basic research intensity does not necessarily promote economic performance, while the promotion effect on social performance needs a lag period of 1 year. Furthermore, enhancing basic research intensity does not necessarily significantly improve international cooperation performance, and even has a significant negative impact after lagged 2 periods. Finally, government support intensity only plays a moderating role between basic research intensity and innovation performance, but not between basic research intensity and other types of performance. This reveals that the government plays a key role in the stage of knowledge production, but its role in the stage of knowledge transformation is relatively limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Data source: Statistical Communique of 2018 National Science and Technology Funding Investment http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/rdpcgb/qgkjjftrtjgb/201908/t20190830_1694754.html.

Data Source: Recipient of the 2018 People's Republic of China International Science and Technology Cooperation Award http://www.most.gov.cn/ztzl/gjkxjsjldh/jldh2018/jldh18jlgg/201812/t20181226_144349.htm.

Chinese universities have a distinct hierarchy based on the quality of teaching and social reputation. Among them, the best university is 985 university, followed by 211 (not 985) university and finally other universities. As both 211 and 985 universities are in charge of the central government and have higher social recognition. Therefore, existing studies usually regard 211 and 985 universities as key universities in China (Yang 2014).

Data source: Statistical Survey - Department of Science and Technology - Government Portal of Ministry of Education, PRC http://www.moe.gov.cn/s78/A16/A16_tjdc/.

Due to the limitation of text length, only the abbreviated names of universities are listed here. The abbreviation is based on the name of E-mail box of each university. The specific universities are as follows. PKU RUC TSU BJTU USTB BUCT BUPT CAU BJFU BUCM BNU CUC CUPL NCEPU CUMTB CUP CUGB NKU TJU DLUT NEU JLU NENU NEFU FDU TONGJI SJTU ECUST DHU ECNU NJU SEU CMUT HHU JNU NJAU CPU ZJU HFUT XMU SDU OUC UPC WHU HUST CUG WUT HZAU CCNU HNU CSU SYSU SCUT CQU SWU SCU SWJTU UESTC XJTU XDU CHD NAFU SXNU.

For example, regulations of the State on S&T Awards clearly points out that the state highest S&T awards are awarded to those who have made major breakthroughs in the frontiers of contemporary S&T or have made outstanding contributions in the development of S&T, and creating enormous economic or social benefits in S&T innovation, the transformation of S&T achievements and industrialization of high technology. http://www.most.gov.cn/ztzl/gjkxjsjldh/jldh2018/jldh18xgwj/201901/t20190107_144580.htm.

It is important to note that Chinese universities have a certain requirement in choosing international cooperation universities. That is, they are seeking cooperation with universities that are better than them. For example, the Notice of Nanjing Normal University on the Application for the Second batch of International Partnership Program clearly points out that overseas high-level universities with advantageous disciplines (the top 500 universities in the world) are the cooperation objects. http://www.njnu.edu.cn/info/1098/12433.htm.

References

Aghion, P., & Jaravel, X. (2015). Knowledge spillovers, innovation and growth. The Economic Journal, 125(583), 533–573.

Auranen, O., & Nieminen, M. (2010). University research funding and publication performance—An international comparison. Research Policy, 39(6), 822–834.

Belenzon, S., & Schankerman, M. (2015). Motivation and sorting of human capital in open innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 795–820.

Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2017). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425–469.

Bourke, J., & Roper, S. (2017). Innovation, quality management and learning: Short-term and longer-term effects. Research Policy, 46(8), 1505–1518.

Bradley, D., Kim, I., & Tian, X. (2016). Do unions affect innovation? Management Science, 63(7), 2251–2271.

Bronzini, R., & Piselli, P. (2016). The impact of R&D subsidies on firm innovation. Research Policy, 45(2), 442–457.

Cao, Q. (2020). Contradiction between input and output of Chinese scientific research: a multidimensional analysis. Scientometrics, 123, 451–485.

Chen, Q. (2014). Advanced Econometrics and Stata Applications. Beijing: Higher Education Press.

Chen, A., Patton, D., & Kenney, M. (2016). University technology transfer in China: a literature review and taxonomy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(5), 891–929.

Cooper, S. (2017). Corporate social performance: A stakeholder approach. London: Routledge.

Dang, J., & Motohashi, K. (2015). Patent statistics: A good indicator for innovation in China? Patent subsidy program impacts on patent quality. China Economic Review, 35, 137–155.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Dziallas, M., & Blind, K. (2019). Innovation indicators throughout the innovation process: An extensive literature analysis. Technovation, 80, 3–29.

Garcia Martinez, M., Zouaghi, F., & Garcia Marco, T. (2017). Diversity is strategy: the effect of R&D team diversity on innovative performance. R&D Management, 47(2), 311–329.

Georghiou, L. (1998). Global cooperation in research. Research Policy, 27(6), 611–626.

Gersbach, H., & Schneider, M. T. (2015). On the global supply of basic research. Journal of Monetary Economics, 75, 123–137.

Gong, H., & Peng, S. (2018). Effects of patent policy on innovation outputs and commercialization: evidence from universities in China. Scientometrics, 117, 687–703.

Grande, E., & Peschke, A. (1999). Transnational cooperation and policy networks in European science policy-making. Research Policy, 28(1), 43–61.

Guan, J. C., & Chen, K. H. (2012). Modeling the relative efficiency of national innovation systems. Research Policy, 41(1), 102–115.

Guan, J., & Yam, R. C. (2015). Effects of government financial incentives on firms’ innovation performance in China: Evidences from Beijing in the 1990s. Research Policy, 44(1), 273–282.

Guo, D., Guo, Y., & Jiang, K. (2016). Government-subsidized R&D and firm innovation: Evidence from China. Research Policy, 45(6), 1129–1144.

Gupta, K., Banerjee, R., & Onur, I. (2017). The effects of R&D and competition on firm value: International evidence. International Review of Economics & Finance, 51, 391–404.

Hahn, T., Pinkse, J., Preuss, L., & Figge, F. (2016). Ambidexterity for corporate social performance. Organization Studies, 37(2), 213–235.

Harrison, J. S., & Berman, S. L. (2016). Corporate social performance and economic cycles. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(2), 279–294.

Heitor, M. (2015). How university global partnerships may facilitate a new era of international affairs and foster political and economic relations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 95, 276–293.

Hong, J., Feng, B., Wu, Y., & Wang, L. (2016). Do government grants promote innovation efficiency in China’s high-tech industries? Technovation, 57, 4–13.

Hong, J., Hong, S., Wang, L., Xu, Y., & Zhao, D. (2015). Government grants, private R&D funding and innovation efficiency in transition economy. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 27(9), 1068–1096.

Howell, S. T. (2017). Financing innovation: Evidence from R&D grants. American Economic Review, 107(4), 1136–1164.

Huang, C., Su, J., Xie, X., & Li, J. (2014). Basic research is overshadowed by applied research in China: a policy perspective. Scientometrics, 99(3), 689–694.

Huergo, E., & Moreno, L. (2017). Subsidies or loans? Evaluating the impact of R&D support programmes. Research Policy, 46(7), 1198–1214.

Jung, E. Y., & Liu, X. (2019). The different effects of basic research in enterprises on economic growth: Income-level quantile analysis. Science and Public Policy, 46(4), 570–588.

Kianto, A., Sáenz, J., & Aramburu, N. (2017). Knowledge-based human resource management practices, intellectual capital and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 81, 11–20.

Liao, C. H. (2010). How to improve research quality? Examining the impacts of collaboration intensity and member diversity in collaboration networks. Scientometrics, 86(3), 747–761.

Lightfield, E. T. (1971). Output and recognition of sociologists. The American Sociologist, 6(2), 128–133.

Liu, F. C., Simon, D. F., Sun, Y. T., & Cao, C. (2011). China’s innovation policies: Evolution, institutional structure, and trajectory. Research Policy, 40(7), 917–931.

Martin, B. (1996). The use of multiple indicators in the assessment of basic research. Scientometrics, 36(3), 343–362.

Martinez-Senra, A. I., Quintas, M. A., Sartal, A., & Vázquez, X. H. (2015). How can firms’ basic research turn into product innovation? The role of absorptive capacity and industry appropriability. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 62(2), 205–216.

Martinsuo, M., & Poskela, J. (2011). Use of evaluation criteria and innovation performance in the front end of innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28(6), 896–914.

Miller, K., McAdam, R., & McAdam, M. (2018). A systematic literature review of university technology transfer from a quadruple helix perspective: toward a research agenda. R&D Management, 48(1), 7–24.

Mowery, D. C. (1998). The changing structure of the US national innovation system: implications for international conflict and cooperation in R&D policy. Research Policy, 27(6), 639–654.

Nason, R. S., Bacq, S., & Gras, D. (2018). A behavioral theory of social performance: Social identity and stakeholder expectations. Academy of Management Review, 43(2), 259–283.

North D.(1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. MA: Harvard University Press.

Pavitt, K. (1991). What makes basic research economically useful? Research Policy, 20(2), 109–119.

Payumo, J., Sutton, T., Brown, D., Nordquist, D., Evans, M., Moore, D., et al. (2017). Input-output analysis of international research collaborations: A case study of five U.S. universities. Scientometric, 111(3), 1657–1671.

Peloza, J. (2009). The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1518–1541.

Peng, M. W., Wang, D. Y., & Jiang, Y. (2008). An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5), 920–936.

Pfeffer J, Salancik GR (2003) The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Stanford University Press, Redwood City

Prettner, K., & Werner, K. (2016). Why it pays off to pay us well: The impact of basic research on economic growth and welfare. Research Policy, 45(5), 1075–1090.

Richardson, J., & McKenna, S. (2003). International experience and academic careers: what do academics have to say? Personnel Review, 32(6), 774–795.

Rodriguez, V., & Soeparwata, A. (2015). The Governance of Science, Technology and Innovation in ASEAN and Its Member States. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 6(2), 228–249.

Rogowski, R. (2015). Rational legitimacy: A theory of political support. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Saeidi, S. P., Sofian, S., Saeidi, P., Saeidi, S. P., & Saaeidi, S. A. (2015). How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 341–350.

Salter, A. J., & Martin, B. R. (2001). The economic benefits of publicly funded basic research: a critical review. Research Policy, 30(3), 509–532.

Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Song, M., Pan, X., Pan, X., & Jiao, Z. (2019). Influence of basic research investment on corporate performance: Exploring the moderating effect of human capital structure. Management Decision, 57(8), 1839–1856.

Szczygielski, K., Grabowski, W., Pamukcu, M. T., & Tandogan, V. S. (2017). Does government support for private innovation matter? Firm-level evidence from two catching-up countries. Research Policy, 46(1), 219–237.

Toole, A. A. (2012). The impact of public basic research on industrial innovation: Evidence from the pharmaceutical industry. Research Policy, 41(1), 1–12.

Tsai, K. H. (2009). Collaborative networks and product innovation performance: Toward a contingency perspective. Research Policy, 38(5), 765–778.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2016). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. CA: Nelson Education.

Wu, A. (2017). The signal effect of Government R&D Subsidies in China: Does ownership matter? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 117, 339–345.

Yan, C. L., & Gong, L. T. (2013). R&D ratio, R&D structure and economic growth. Nankai Economic Studies, 2, 3–19.

Yang, G. (2014). Are all admission sub-tests created equal? — Evidence from a National Key University in China. China Economic Review, 30, 600–617.

Yang, W. (2016). Policy: Boost basic research in China. Nature News, 534(7608), 467.

Yu, F., Guo, Y., Le-Nguyen, K., Barnes, S. J., & Zhang, W. (2016). The impact of government subsidies and enterprises’ R&D investment: A panel data study from renewable energy in China. Energy Policy, 89, 106–113.

Zhou, K. Z., Gao, G. Y., & Zhao, H. (2017). State ownership and firm innovation in China: An integrated view of institutional and efficiency logics. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(2), 375–404.

Acknowledgement

This research is supported by the major specific project of National Social Science Foundation of China (number: 18VSJ058). We are very grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which have greatly improved the quality of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, Q., Cao, Q. & Tan, M. Basic research intensity and diversified performance: the moderating role of government support intensity. Scientometrics 125, 577–605 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03635-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03635-x