Abstract

This study explores the international profiles in collaboration and mobility of countries included in the so-called “travel bans” implemented by US President Trump as executive order in 2017. The objective of this research is to analyze the exchange of knowledge between countries and the relative importance of specific countries in order to inform evidence-based science policy. The work serves as a proof-of-concept of the utility of asymmetry and affinity indexes for collaboration and mobility. Comparative analyses of these indicators can be useful for informing immigration policies and motivating collaboration and mobility relationships—emphasizing the importance of geographic and cultural similarities. Egocentric and relational perspectives are analyzed to provide various lenses on the importance of countries. Our analysis suggests that comparisons of collaboration and mobility from an affinity perspective can identify discrepancies between levels of collaboration and mobility. This approach can inform international immigration policies and, if extended, demonstrate potential partnerships at several levels of analysis (e.g., institutional, sectoral, state/province).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Immigration is heralded as a key contemporary policy issue (Duncan 2017; Bildt 2017). Across the globe, political leaders are proposing and implementing nationalistic policies that restrict global mobility. One notable example is the executive order signed by United States President Trump on January 27, 2017, temporarily suspending entry of individuals from seven countries (i.e., Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen) and placing restrictions on visa renewals for an additional 38 countries. Following the initial order, new restrictions were announced and the third and latest version (September 2017)Footnote 1 added countries to the original list (Chad, North Korea, and Venezuela), while Sudan and Iraq were removed. When the first executive order was signed, scientists home and abroad decried the order as impeding science, providing anecdotes of students, postdocs, and researchers who were trapped either home or abroad and unable to continue in their scientific activities (Morello and Reardon 2017; Reardon 2017). However, there was little in the way of evidence of the scientific relationships among these countries and implications for the scientific community.

Such restrictions can potentially affect the dynamics of the global scientific system, which has experienced exponential growth of scientific connections over the last century (Larivière et al. 2015). Collaboration in science highlighted increased partnerships between scientific advanced and emergent countries in terms of co-authoring scientific papers (Adams 2013), as well as at the global level (Wagner et al. 2015). That translates in strong benefits for participating countries (Glänzel 2001) and institutions (Gazni et al. 2012) in terms of citations. Collaboration for mutual benefit has also gained increasing acceptance, with “partner” selection becoming a strategic priority to enhance one’s own production (Chinchilla-Rodríguez et al. 2018). However, less understood is how scientists from different countries establish ties through migration. The use of bibliometric methods, in particular, has received scant attention, with a few notable exceptions at the individual (Laudel 2003) and country level (Moed and Halevi 2014; Sugimoto et al. 2016, 2017).

This paper extends on previous bibliometric studies of mobility in order to demonstrate insights that can be gained by examining multiple forms of scientific partnerships in concert. We present an approach that measures proportional production and probabilistic affinities for both collaboration and mobility, to describe country linkages within the global scientific system. Furthermore, we compare these two indicators of connectivity—collaboration and mobility—to provide a more refined understanding of the role of certain countries in the global knowledge network. We use the countries included in the so-called “travel bans” as a proof-of-concept for this approach.

The vast differences in volume of production and scientific capacity by country complicate analyses of collaboration (Melin 1999). Furthermore, the existence of collaboration and mobility between two countries implies reciprocity but not necessarily symmetry. This is well-understood in network science: the degree of reciprocity is determined not by the definition of the link but by the extent to which two nodes report the same ties with one another and the proportion that these ties represent based on connections with the rest of the network (Tichy et al. 1979). Several indices exist to measure network asymmetries (Luukkonen et al. 1993; Glänzel and Schubert 2001; Eck and Waltman 2009). Among them, two particular indices—Affinity Index (AFI) and Probabilistic Affinity Index (PAI) or Proximity Index (PRI)—have been used to measure the relative strength of scientific linkages in science. The first one is size-dependent, and the latter is size-independent (Zitt et al. 2000). AFI allows for the calibration of relative importance and asymmetries between countries, measuring the amount of collaborative papers published jointly and the total number of international collaborations of each country. In a similar way, taking into account all the potential partners in the network and by removing the size dependency, PAI reveals the association strength of countries, i.e., affinities that are largely dependent upon different drivers of scientific collaboration and mobility. In particular, the probabilistic affinity index is highly sensitive and reveals the limit of the scientific sizes as a predictor of relationships.

Choosing an appropriate similarity measure is also critical for analyses of country-level partnerships. Within the field of scientometrics, association strength has been recommended as preferable (Eck and Waltman 2009) over other similarity measures (e.g., cosine, inclusion index or Jaccard index). Previous studies have employed AFI and/or PAI to analyze the level of similarity in different fields of science (Okubo et al. 1992), the “continentalization of science” (Leclerc and Gagné 1994), the effects of historical, cultural and linguistic proximities in stablishing partnerships in consolidated scientific systems (Zitt et al. 2000), inter-sectoral cooperation between two countries (Yamashita and Okubo 2006), and the strength of scientific linkages among the emergent countries (Finardi and Buratti 2016). But no previous study has, to the best of our knowledge, applied these measures to analyze the connections constructed through mobility. While the analysis of collaboration and mobility usually focuses on advanced countries (e.g., those included in OECD surveys), many countries fall outside of this scope. The set of countries banned under the travel ban offers the opportunity to showcase dimensions of connectivity of nations with different scientific sizes, stages of development (in terms of income) and research capacities, which are absent in many bibliometric studies.

Objectives

Methods are necessary to understand more comprehensively the relationship between countries, particularly those that tend to be obscured from analyses focused on elite countries. This is motivated, in part, by the rise of nationalistic policies which threaten the exchange of scholars at the global level. This proof-of-concept study attempts to move from anecdote to empiricism by looking affinities and association strength rather than raw co-authorship or mobility numbers with the justification that, even if there are only a few publications or researchers in mobility, these could be proportionally important partnerships from the perspective of the non-elite country. This analysis focuses on four dimensions of partnership strength for each of the ten countries for which visas were temporarily suspended as well as the United States: (a) asymmetry of collaboration, (b) asymmetry of mobility, (c) association strength for collaboration, and (d) association strength for mobility. The first two dimensions allow us to identify the main partners for a country considering their asymmetrical relationships, and the latter two reveal what the stronger and preferred partners are considering all the potential countries. We provide collaboration and mobility in parallel to highlight the different insights that can be gained by examining these indicators in concert, rather than independently.

Data and methods

By using affiliation data from scientific publications, it is possible to track the trajectory of individual scientists and analyze collaboration and mobility patterns at meso and macro levels (Moed and Halevi 2014; Sugimoto et al. 2017; Wagner et al. 2018). A bibliometric approach allows us to conduct a comparative study of number of mobile researchers and the amount of internationally co-authored papers countries have. In this study, we use co-authorship as a measure to examine international collaboration and the number of affiliations of scholars with different countries as a proxy of international mobility (Sugimoto et al. 2017) in a sample composed of ten countries involved in the US immigration ban—Chad, Iran, Iraq, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen—and the United States. We define a researcher as mobile as those who are affiliated, at any point of their research trajectory, to more than one country. Further details on the methodology followed to track international mobility is provided by Robinson-Garcia et al. (2018).

This study uses the in-house version of the Web of Science (WoS) maintained at CWTS of Leiden University. Nation-to-nation links were collected from 13,699,176 distinct publications (UT codes) retrieved from WoS for the 2008–2015 period, yielding connections among 216 countries. Unique authors were identified using a large-scale author disambiguation algorithm applied to the in-house CWTS version of the Web of Science (Caron and van Eck 2014). This algorithm clusters publications that belong to a single author based on a set of similar publication patterns (co-authorship network, address data, etc.). This resulted in a total of 15,931,847 authors, 595,891 of which were affiliated with more than one country (3.7%). For collaboration linkages, we included all authors and all document types: this yielded 2718,556 publications (20% of the total) with international coauthoring. Reprint affiliations were included for both collaboration and mobility data.

Country names were cleaned and standardized (e.g., merging Timor-Leste and East Timor, Congo and Republic of Congo as well as Zaire and the Democratic Republic of Congo). The cleaning resulted in 212 countries. We then enriched this data by adding additional several country-level classifications. Income level category, as defined by the World Bank (2016) was used as a proxy for economic capacity. The Scientific Technological and Capacity Index (Wagner et al. 2001) was used as an indicator of scientific capacity. This index categorizes countries into four groups of unequal sizes: advanced (n = 22), proficient (n = 24), developing (n = 22), and lagging (n = 80). In the present study, an additional group (“other”) is added to account for the 66 countries that were not placed in the Wagner et al. (2001) classification. Every country was assigned to one of seven geographical regions defined by the World Bank (2016): East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, South Asia and, Sub-Saharan Africa.

Full-counting is used to attribute credit to authors for collaboration and mobility. Thus, the sum of publications and authors exceeds the total number of publications. From these data, we calculate the following indicators (Table 1):

To measure the asymmetry in collaboration and mobility patterns, we use a pair of inclusion indexes \(: AFI\left( {i,j} \right)\), and counterpart, \(AFI\left( {j,i} \right)\), with one-way normalization (Zitt et al. 2000). AFI is a measure of the links between a given country (i) with another country (j), compared to the total links country (j) with the entire world during the same period. \(AFI\left( {j,i} \right)\) is calculated as:

\(AFI\left( {i,j} \right) = \frac{{n\left( {i,j} \right)}}{n\left( i \right)}\), where n(i, j) is the volume of links between countries i and j, and n(i) = ∑j n(i, j), total coauthorship linkage of i. This index is size-dependent given that the preference for partner j in \(AFI\left( {i,j} \right)\) is influenced by the global size of j (conversely, preference is dependent upon the size of i for \(AFI\left( {j,i} \right)\). This index highlights the important partners in terms of quantity and demonstrates asymmetry in parternships.

To normalize by the size of both countries, we employ the Probabilistic Affinity Index (PAI), used in science policy to demonstrate the degree to which proximity (both material and immaterial) contributes to scientific relationships among the countries. It indicates the intensity of scientific exchanges between two countries, according to coauthored articles measured and collaborations/mobility theoretically expected. An index above 0 reflects higher collaboration/mobility strength between two countries than their respective weight and propensity to collaborate would indicate. The index is capable of demonstrating strong relationships with small countries and presents the strength of relationships in their global context. For PAI, we refer to Zitt et al. (2000)’s algorithm and apply it to calculate the relationships between countries for both collaboration and mobility:

\(PAI\left( {i,j} \right) = \frac{{\left[ {n\left( \ldots \right)n\left( {i,j} \right)/n\left( i \right)n\left( j \right)} \right]^{2} - 1}}{{\left[ {n\left( \ldots \right)n\left( {i,j} \right)/n\left( i \right)n\left( j \right)} \right]^{2} + 1}}\), where \(n\left( i \right) = \sum\nolimits_{j} {n\left( {i,j} \right)}\) and \(n\left( \ldots \right) = \sum\nolimits_{i \ne j} {n\left( {i,j} \right)}\). In this way, PAI is normalized into [− 1, 1].

Each indicator yields a different lens on the international portfolio of a given country. The affinity index reveals asymmetries, demonstrating that collaborations with country i might constitute a large portion of the total collaborations of country i, but a small proportion of the collaborations of country j. It simultaneously provides an indicator of the main collaborators in the global network. PAI, on the other hand, highlights the strengths of countries that might not have high output, but have disproportionately strong connections in the global environment. We present, for both collaboration and mobility, the 50 main and preferred partners for the countries in our sample, according to the AFI and PAI.

Results

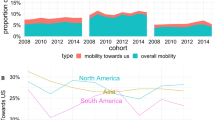

Overview of collaboration and mobility

Table 2 illustrates the shares of internationally mobile scholars, internationally co-authored papers and total numbers of publications and scholars identified for each of our analyzed set of countries. All of these differ in both economic and scientific dimensions. Iran, Iraq, Libya, and Venezuela are economically considered as upper-level income countries, whereas Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are in the lower-middle income bracket for countries. North Korea, Chad, and Somalia are in the lowest income level. Somalia is also distinct in terms of the profile of scientific output and the size of the scientific workforce—having the lowest of both for the ten. Iran is the most prolific country in the set—contributing 1.4% of the share of world publications, placing it in 22th place worldwide in terms of scientific output. The next most productive countries in the set are Venezuela and Iraq, which ranked 63th and 82nd globally in terms of production and produce 0.08 and 0.05% of the world output.

With regard to international collaboration, we observe that nearly all publications from Somalia and Chad are authored with an international partner, whereas only a 20.8% of publications from Iran are the result of international collaboration, less even than the United States (27.4%). Iran, Sudan, and Venezuela have the widest collaboration portfolios in terms of number of international partners—reaching 79, 75 and 70% (respectively) of potential collaborative partners in this dataset. North Korea and Somalia have the fewest, reaching 15 and 22% of potential partnerships.

In all countries, the proportion of mobile authors drops dramatically in comparison with the proportion of international collaborative papers. Iran is the only country that remains stable across the two lists—appearing as both the least collaborative and the country with the lowest percentage of mobile researchers. However, even with the lower degree of mobility, it still reaches nearly 46% of potential mobility countries, second in this set only to the United States (at 95% in mobility and 99.5% in collaboration). This situation seems to be common in the set of countries where it is possible to observe different degrees of magnitude. Wide differences can be observed between collaboration and mobility: for example, Somali researchers collaborate with four times as many countries as those with whom they have mobility partnerships. In all cases, collaboration is more prevalent that mobility.

Tables 3 and 4 show the main partners in mobility and in collaboration with each country according to their scientific capacities and geographical region. The dominant partners for both dimensions of connectivity are scientifically “advanced” countries (Table 2). Yemen is the exception, collaborating mainly with “lagging” countries. Apart from Venezuela and North Korea, all countries have a demonstrable share of connections with lagging countries, when compared to “developing” and “proficient” countries showing homophily in their international relationships. In the case of North Korea, the most important partners are proficient countries.

At the geographical level, Europe and Central Asia represent the dominant partner region for most of the selected countries, with some exceptions (Table 4). For example, the plurality of Iraq’s mobility and collaboration partnerships are with East Asia and the Pacific. Regional affiliations are also apparent: Somalia and Chad have a prominent degree of partnership with Sub-Saharan Africa, whereas Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Sudan have strong ties with the Middle East and North Africa. After Europe and Central Asia, the US is the most dominant partner for Iran.

Country-specific analysis

Iran

High producing and advanced countries, such as the United States and Canada, lead in terms of the top connections for both collaboration and mobility when considering the AFI for Iran (Fig. 1). For example, Iran publishes more than 22% of internationally collaborative publications with the US and 20% of Iranian researchers (those for whom their first publication was in Iran) have been affiliated with the US. However, Iran also has a strong connection with Malaysia—a scientifically lagging country with upper middle income. Among the countries with the strongest ties, collaboration is stronger with the US, Germany, and the United Kingdom than mobility, whereas the inverse is true with Canada and Malaysia. Overall, using AFI as the measurement, Iran tends to have stronger relationships in terms of collaboration than mobility.

PAI presents a very different portfolio in terms of international connections. The strongest partners using this index include Malaysia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Iraq, Canada, and Oman—reinforcing the importance of geographical, linguistic, and cultural ties. Canada remains highly ranked according to this index, especially in mobility. The United States, however, drops considerably in the ranking and the United Kingdom show a negative index in both dimensions of connectivity, collaboration, and mobility. Though they exchange intensively in gross volume, their level of connectivity is much lower than what would be expected, which means that they are “elective partners” in terms of probabilistic affinities, neither an important nor a preferred partner for Iran, especially for United Kingdom. As with AFI, overall the connection with some countries on the PAI is stronger with collaboration than mobility. This preference is invariable across the 50 preferred partners for Iran. Several countries have a very high probability index for collaboration, but negative ranks for mobility. These include several Middle East countries (i.e., Pakistan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia) and New Zealand and India. This may suggest potential avenues for mobility programs (Figs. 2, 3, 4).

Venezuela

The country reveals an uneven connectivity between partnerships in international collaboration and mobility. Venezuela collaborates with 150 countries and has mobility connections with 59, reaching 70 and 28% of collaboration and mobility portfolios in terms of number of international partners. As measured with AFI, the main partners are Spain, the USA, Mexico, and France, with the United States as a stronger partner in collaboration. However, the preferred partners are all Latin American countries and Spain showing language as a driver of connectivity. The comparison between collaboration and mobility using PAI reveals gaps in partnerships. For example, Venezuela has strong associations for collaboration with Brazil and Nigeria, but no mobility.

Iraq

Iraq collaborates with 117 countries and has researchers with mobility connections with 59, including Palau, with whom there are no collaborations in common. As measured with AFI, Malaysia captures the largest share of collaboration and mobility relations with Iraq, followed by the UK, the US, China, Australia, and Germany. Some European countries (i.e., Germany, Italy, and France) have demonstrably higher AFI indexes in collaboration than mobility; however, for the most part, there is an evenness in the collaboration and mobility patterns for Iraq according to AFI.

Taking into consideration all potential partners with PAI, the strongest relationships are with the Middle East, Asiatic region, and some African and Eastern European countries (Romania). Among the most developed countries, only the United Kingdom is preferred, especially in mobility. In contrast, Iraq shows low affinities with China, Germany, and the USA. This suggests that some scientifically developed countries located in Europe, the Pacific region, and Asia are acting as bridges by enhancing the connectivity of Iraqi science. As with Iran, the comparison between collaboration and mobility using PAI reveals gaps in partnerships. For example, Iraq has strong affinities for collaboration with Egypt, India, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia but no mobility. There are, of course, political explanations for these discrepancies, but the measurement provides a neutral way to identify communities that have demonstrated scientific affinities (i.e., through collaboration) which could be explored in further policy initiatives.

Sudan

Nearly three-quarters of Sudan outputs (72.7%) result from international collaboration with 160 countries. More than 18% of Sudanese authors have mobility, linking Sudan with 66 countries. In terms of size, Sudan’s main partners in mobility are Saudi Arabia (17%), China, Malaysia, Germany, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the USA (5.5%); while the collaborative partners are different—the US is the top collaborative partner followed by the United Kingdom, and Germany. Similar to Iran, collaboration tends to be much higher in all cases than mobility, as measured by AFI.

When correcting for size, the strongest partners come from three different zones of influence constituted by the geographical linkages with African countries (Uganda, Ethiopia, South Africa, Kenya, Ghana, and Egypt), Middle East countries (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen), and Asian countries (Malaysia, United Arab Emirates and Pakistan). In the case of Sudan, proximity and language matters in the strength of the relationships, with the exception of Malaysia. Among the advanced countries, Norway, Netherlands and Sweden are strongest in mobility than in collaboration, whereas in some Africans countries (i.e., Tanzania and Nigeria) is strongest in collaboration. This may indicate avenues for potential collaboration between these advanced countries and Sudan, a lagging country.

Syria

As seen in Table 4 and Fig. 5, Syria has mobility ties with 62 countries (29% of all potential partners) and collaborates with 139 (65.6%). Around 60% of Syria’s output is the result of international collaboration while Syrian author’s mobility is close to 20%. As with the other countries, Syria does not have a parallel relationship between collaboration and mobility—the US, for instance, has the highest collaboration by AFI but ranks fourth by mobility. France, Germany, and the UK are strong partners on both dimensions. Across the top 50 countries, Syria has a pronounced emphasis on collaboration over mobility. PAI again shows the importance of socio-cultural factors in establishing collaborative ties. Syria’s preferred partners in this index include the Middle East, Asian and African countries. A second preferential zone is formed by some European countries—including France and Germany. The US is not a preferred partner, demonstrating low degrees of mobility, despite fairly high levels of collaborative affinity. Syria has several countries in its profile with extreme differences in affinity between collaboration and mobility, including Turkey, Malaysia, Pakistan and Iran.

Libya

Libya has collaborative partnerships with 122 countries and mobility ties with 45 countries (including Lesotho, Kyrgyzstan, Mauritius, and the West Indies with which Libya has no collaborative papers). In gross volume, the main partners in collaboration are the United Kingdom (23%), Egypt, France, Malaysia, India, and the USA. Collaboration is the dominant form of connection (Fig. 6).

The preferred partners are Dominica, Middle East countries (i.e., Lebanon, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Egypt, and Syria), Asiatic countries (i.e., Brunei, Malaysia) and some African countries such as Angola. The second zone of influence comprised European countries (i.e., Finland, Serbia, Greece) and the United Kingdom. The Unites States is not a preferred partner. Libya’s collaboration and mobility ties with many African countries are much lower than would be expected, given the global scientific network. However, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco appear as strong partners in collaboration with no relevant mobility ties.

Yemen

Yemen collaborates with 111 countries and has mobility connections only with 38 countries (these are not entirely overlapping units, as there is mobility, but no collaborative publications with Madagascar). The strongest partners in terms of size include Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and India. By the AFI, the US is ranked fourth in terms of collaboration and mobility (14 and 6.6% respectively). Yemen demonstrates a higher degree of collaboration than mobility by AFI. Using PAI, the strongest ties are with Malaysia and Middle East countries (Syria, Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Iraq, Qatar, Jordan, and Kuwait). Among the African countries, Yemen has strong connections with Madagascar—just in mobility, Rwanda, Sudan, Algeria and Cameroon. When considering the entire global context, Yemen has several African countries for whom there are less than expected values for mobility, including Morocco, Libya, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Tunisia and Kenya (Fig. 7).

North Korea

Despite having higher numbers of international collaborative papers and mobile researchers than Chad and Somalia, North Korea has the lowest proportions of potential partners in collaboration (32 and 12 countries respectively; 15 and 5.6% respectively). In gross volume, the main partners in collaboration are China, Germany, South Korea, Australia, the USA, and the UK. Preferred partners are Laos, China. South Korea and Romania are stronger partners in mobility than in collaboration, whereas Germany, Cambodia, Uganda, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Kenya, are preferred partners in collaboration (Fig. 8).

Chad

Nearly 94% of Chad’s output is co-authored with 64 different nations and the country has mobile researchers in 17 countries (20%).The main partners in mobility are France, Cameroon, Niger, Switzerland, the USA, Germany, and Senegal. In collaboration, the UK ranks in the fourth position but there are not mobile researchers. As measured with PAI, the strongest associations take place with others African and French-speaking countries such as Niger, Cameroon, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Uganda, Algeria, and France. In the second zone of influence, Czech Republic is a preferred partner in mobility and Switzerland and Belgium in collaboration.

Somalia

Somalia has the lowest rate of publication across the ten countries, with collaborative ties with 47 countries and mobility ties with only nine. The US is the fourth most important partner in AFI, after Kenya, Malaysia, and the United Kingdom. Somalia is outperforming expected collaboration rates in all countries and is underperforming expected values of mobility in all countries, with the exception of Kenya and Malaysia.

The United States

Given that our proof-of-concept study focuses on the relationship of the US with the ten countries in the executive orders, it is necessary to also take an egocentric analysis of the US for context. The US has one of the lowest levels of international collaboration due to size and scientific capacity but serves as the dominant collaboration for nearly all countries across the world. We provide both the top 50 connections, but also the countries in the examination (the fact that these do not overlap suggests the comparatively weaker relationship between these countries from the perspective of the US).

According to AFI, the strongest partners include (in order of importance) China, the UK, Germany, Canada, France, Japan, South Korea, Italy, Australia, Switzerland, and Spain. Collaboration rates are higher than mobility rates for all countries except for China and India, the United Arab Emirates, and Turkey where the percentages are slightly higher (China: 20% for collaboration and 15% for mobility; India 2.7% for collaboration and 3.17% for mobility; United Arab Emirates 0.22 and 0.24%, and Turkey with the same percentage in both). When size dependence is removed, South Korea and China are the main mobility partners with the US, followed by Israel, Lebanon, Taiwan, Peru, Uganda, Turkey and Canada; whereas in collaboration Canada, Kenya, Japan, Singapore, the UK, Germany and Australia perform better than in mobility.

Limitations and further analysis

This study requires further analysis in order to overcome some of the limitations and respond to other important questions related to the scientific capacities and socio-economic conditions of countries. The data examines only those authors whose first publication occurred in or after 2008. This provides only limited diachronic analysis. More data and analysis are necessary to further inform a longitudinal analysis of collaboration and migration patterns. There is a general limitation of collaboration analysis based on author affiliations and further analysis should be done to minimize the inflationary effect that creates some overlaps when we are comparing collaboration and mobility. In further research, we intend to complement our analysis with a time component, allowing us to analyze some key points such as authors’ choices regarding institution address selection from publication data. This will facilitate the analysis of causal relationships, examining the relationship between collaboration and migration as well as the effects of policies and political action (Hottenrott and Lawson 2017). We also plan to analyze positions occupied in the bylines of co-authorship, the impact of publications as a result of these relationships, the institutional reputation of destinations, and the degree to which topic changes occur as a result of these interactions. At the methodological level, approaches with different counting methods (Perianes-Rodriguez et al. 2016) and scale-adjusted metrics will be explored in order to assure an accurate comparison of relational capacities of countries with different sizes and capacities (Katz 2000; Archambault et al. 2011; Finardi and Buratti 2016). There are also several other elements, such as the thematic specialization of science, which should be taken into account when analyzing collaborative preferences between countries (Glänzel 2000; Radosevic and Yoruk 2014).

Discussion

This work presents a case study of the application of asymmetry and similarity measures to better understand the implications of immigration policies. Using a set of countries suspended in the 2017 US executive orders, we present an egocentric view of each country involved in order to analyze the strength and reciprocity of the relationships of each of the various countries with the US and with other preferred partners. Although similarity measures have long been used to analyze international collaboration, this is the first analysis to explore the insights gained when mobility and collaboration are analyzed in parallel. For the case under study, we demonstrated an asymmetrical relationship between each of these countries and the US—the US was a dominant country in terms of collaboration and mobility for the ten countries, though they represented a small fraction of the share of US scientific relationships. Of the ten, Iran and Venezuela were the most important scientific countries for the US.

Internationalization of science affects the research performance of countries and in certain degree depends on the attractiveness of a partner in the global network. The country with which the scientific relationship is established is important for indicator construction, given the unequal magnitude of contributions between partners. The results of this study demonstrate that, despite the low volume of international publications and mobile researchers for many countries, the number of countries reached is relatively high. This internationalization presents policy challenges and opportunities, particularly for developing and lagging countries that are confronted with critical internal conditionsFootnote 2 that often isolate them from countries with high scientific capacity. Despite these barriers, international collaboration seems to respond to the dynamics created by the self-interests of individual scientists rather than to other structural, institutional, or policy-related factors (Wagner and Leydesdorff 2005). This is evident in the degree of internationalization of the countries in our sample, such as North Korea.

Previous studies have revealed different drivers underlying the formation of collaborations networks such as geographical and cultural proximity, thematic similarity, regional partnership, as well as the reputation and attractiveness of the receiving partner (Leclerc and Gagné 1994; Archambault et al. 2011; Adams et al. 2014; Finardi and Buratti 2016). Our results confirmed these pre-existing notions: AFI demonstrated the asymmetries and main partners to countries with high reputation and scientific capacity. PAI reinforced the importance of geographic and linguistic proximity acting as a predictor of scientific partnerships. For example, the United States is not a preferred partner but is one of the most attractive destinations for foreign researchers (Scellato et al. 2014; Sugimoto et al. 2017). Large countries, like the US, have extremely high breadth across the scientific network—serving as a collaborative partner with all and a mobile partner for many. Smaller countries, in turn, rely upon international collaboration for a large share of their output. However, there is a distinct lack of reciprocity in terms of mobility. Whereas there are established scientific similarities, given collaborative partnerships, this does not necessarily lead to increased mobility. Mobility, therefore, is a more selective indicator; while collaborations can be established without colocation, mobility—even in the case of co-affiliation—(i.e., researchers with a double appointment with two or more international institutions but keeping ties with their country of origin) often requires some degree of travel and human interaction, having a higher social, human, and economic cost. Mobility is thus likely to be heavily influenced by political environments. Given that the countries in our sample have experienced embargos, invasions, civil wars, and revolutions in the course of the time period under investigation, these are likely to have influenced mobility rates (Moed 2016).

Scientific relationships are highly resource-dependent (Pouris and Ho 2014). However, our analysis has demonstrated the potential utility of combining collaboration and mobility indicators to identify preferred partners, inform policies, and identify potential areas for establishing mobility programs. This method could be extended to multiple levels of analysis, for example, to the institutional level, to examine intra- and inter-national collaboration networks. Further research should investigate the degree to which mobility and collaboration initiatives are successful in facilitating relationships between partners, particularly those that are not already established as preferred or dominant partners, and how to enhance the attractiveness of countries in the global scientific system.

Notes

Iran is under embargos. The invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the Iraqi Civil War since 2014. Second Sudanese Civil War and the now-low-scale war in Darfur. Syrian Civil War inspired by the Arab Spring revolutions since 2011. Yemen is one of the poorest countries in the Middle East with political crisis since 2011 and suffering a Civil War since 2015. The Libyan crisis that lead to the First Libyan Civil War and decades of civil war in Somalia.

References

Adams, J. (2013). The fourth age of research. Nature, 497, 557–560.

Adams, J., Gurney, K., Hook, D., & Leydesdorff, L. (2014). International collaboration clusters in Africa. Scientometrics, 98(1), 547–556.

Archambault, É., Beauchesne, O., Côté G., & Roberge, G. (2011). Scale-adjusted metrics of scientific collaboration. In B. Noyons, P. Ngulube, & J. Leta (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13th international conference of the international society for scientometrics and informetrics (ISSI) (pp. 78–88). Durban.

Bildt, C. (2017). The six issues that will shape the EU in 2017. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/the-six-issues-that-will-shape-the-eu-in-2017/. Accessed April 7, 2017.

Caron, E., & Van Eck, N. J. (2014). Large scale author name disambiguation using rule-based scoring and clustering. In Proceedings of the 19th international conference on science and technology indicators (pp. 79–86).

Chinchilla-Rodríguez, Z., Bu, Y., Robinson-García, N., Costas, R., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2017). Revealing existing and potential partnerships: Affinities and asymmetries in international collaboration and mobility. In Proceedings of ISSI 2017—The 16th international conference on scientometrics and informetrics (pp. 869–880). Wuhan University, China.

Chinchilla-Rodríguez, Z., Miguel, S., Perianes-Rodríguez, A., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2018). Dependencies and autonomy in research performance: Examining nanoscience and nanotechnology in emerging countries. Scientometrics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2652-7.

Duncan, P. (2017). Immigration is key issue with EU referendum voters, according to Google. The Guardian, Retrieved April 7, 2017 from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/15/eu-referendum-immigration-key-issue-with-voters-google.

Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2009). How to normalize co-occurrence data? An analysis of some well-known similarity measures. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(8), 1635–1651.

Finardi, U., & Buratti, A. (2016). Scientific collaboration framework of BRICS countries: An analysis of international coauthorship. Scientometrics, 109, 433–446.

Gazni, A., Sugimoto, C. R., & Didegah, F. (2012). Mapping world scientific collaboration: Authors, institutions, and countries. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(2), 323–335.

Glänzel, W. (2000). Science in Scandinavia: A bibliometric approach. Scientometrics, 49, 357–367.

Glänzel, W. (2001). National characteristics in international scientific co-authorship relations. Scientometrics, 51(1), 69–115.

Glänzel, W., & Schubert, A. (2001). Double effort = double impact? A critical view at international co-authorship in chemistry. Scientometrics, 50(2), 199–214.

Hottenrott, H., & Lawson, C. (2017). A first look at multiple institutional affiliations: A study of authors in Germany, Japan and the UK. Scientometrics, 111(1), 285–295.

Katz, S. J. (2000). Scale-independent indicators and research evaluation. Science and Public Policy, 27(1), 23–26.

Larivière, V., Gingras, Y., Sugimoto, C. R., & Tsou, A. (2015). Team size matters: Collaboration and scientific impacto since 1990. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(7), 1323–1332.

Laudel, G. (2003). Studying the brain drain: Can bibliometric methods help? Scientometrics, 57(2), 215–237.

Leclerc, M., & Gagné, J. (1994). International scientific cooperation: The continentalization of science. Scientometrics, 31(3), 261–292.

Luukkonen, T., Tijssen, R. J. W., Persson, O., & Sivertsen, G. (1993). The measurement of international scientific collaboration. Scientometrics, 28(1), 15–36.

Melin, G. (1999). Impact of national size on research collaboration: A comparison between European and American universities. Scientometrics, 46(1), 161–170.

Moed, H. F. (2016). Iran’s scientific dominance and the emergence of South-East Asian Countries in the Arab Gulf Region. Scientometrics, 108(1), 305–314.

Moed, H., & Halevi, G. (2014). A bibliometric approach to tracking international scientific migration. Scientometrics, 101(3), 1987–2001.

Morello, L., & Reardon, S. (2017). Meet the scientists affected by Trump’s immigration ban. Nature News, 542, 13–14.

Okubo, Y., Miquel, J. F., Frigoletto, L., & Doré, J. C. (1992). Structure of international collaboration in science: Typology of countries through multivariate techniques using a link indicator. Scientometrics, 25(2), 321–351.

Perianes-Rodriguez, A., Waltman, L., & Van Eck, N. J. (2016). Constructing bibliometric networks: A comparison between full and fractional counting. Journal of Informetrics, 10(4), 1178–1195.

Pouris, A., & Ho, Y. (2014). Research emphasis and collaboration in Africa. Scientometrics, 98(3), 2169–2184.

Radosevic, S., & Yoruk, E. (2014). Are there global shifts in the world science base? Analysing the catching up and falling behind of world regions. Scientometrics, 101(3), 1897–1924.

Reardon, S. (2017). How the latest US travel ban could affect science. Nature News, 550, 17.

Robinson-Garcia, N., Sugimoto, C. R., Murray, D., Yegros-Yegros, A., Larivière, V., & Costas, R. (2018). The many faces of mobility: Using bibliometric data to track scientific exchanges. ArXiv: 1803.03449 [Cs]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1803.03449.

Scellato, G., Franzoni, C., & Stephan, P. E. (2014). Migrant scientists and international networks (March 2014). Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Research Paper Series No. 14-07. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2466514 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2466514.

Sugimoto, C. R., Robinson-Garcia, N., & Costas, R. (2016). Towards a global scientific brain: Indicators of researcher mobility using co-affiliation data. In OECD blue sky III forum on science and innovation indicators, Ghent, September 19–21, 2016. http://arxiv.org/abs/1609.06499.

Sugimoto, C. R., Robinson-García, N., Murray, D. R., Yegros-Yegros, A., Costas, R., & Larivière, V. (2017). Scientists have most impact when they are free to move. Nature, 32(550), 29–31.

Tichy, N. M., Tushman, M. L., & Fombrun, C. H. (1979). Social network analysis for organization. The Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 507–519.

Wagner, C. S., Brahmakulam, I., Jackson, B., Wong, A., & Yoda, T. (2001). Science and technology collaboration: Building capacities in developing countries. Santa Monica: RAND.

Wagner, C., & Leydesdorff, L. (2005). Network structure, self-organization, and the growth of international collaboration in science. Research Policy, 34(10), 1608–1618.

Wagner, C. S., Park, H. W., & Leydesdorff, L. (2015). The continuing growth of global cooperation networks in research: A conundrum for national governments. PLoS ONE, 10, e0131816. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131816.

Wagner, C., Whetsell, T., Baas, J., & Jonkers, K. (2018). Openness and impact of leading scientific countries. Frontiers in Research and Analytics. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2018.00010.

World Bank. (2016). World development indicators. Available: http://wdi.worldbank.org/tables/. Accessed October 26, 2016.

Yamashita, Y., & Okubo, Y. (2006). Patterns of scientific collaboration between Japan and France: Inter-sectoral analysis using Probabilistic Partnership Index (PPI). Scientometrics, 68(2), 303–324.

Zitt, M., Bassecoulard, E., & Okubo, Y. (2000). Shadows of past in international cooperation: Collaboration profiles of the top five producers of science. Scientometrics, 47(3), 627–657.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from Mobility Program ‘Salvador de Madariaga 2016’ funded by the Ministry of Education of Spain, the State Programme of Research, Development and Innovation oriented to the Challenges of the Society (Ref. CSO2014-57770-R) funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain, the Science of Science Innovation and Policy program of the National Science Foundation in the United States (NSF #1561299), and the South African DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Scientometrics and Science, Technology and Innovation Policy (SciSTIP) is also acknowledged. The authors thank Ludo Waltman for fruitful discussions on similarity measures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chinchilla-Rodríguez, Z., Bu, Y., Robinson-García, N. et al. Travel bans and scientific mobility: utility of asymmetry and affinity indexes to inform science policy. Scientometrics 116, 569–590 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2738-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2738-2

Keywords

- International collaboration

- Mobility

- US travel ban

- Similarity measures

- Association strength

- Science policy