Abstract

Data on patent families is used in economic and statistical studies for many purposes, including the analysis of patenting strategies of applicants, the monitoring of the globalization of inventions and the comparison of the inventive performance and stock of technological knowledge of different countries. Most of these studies take family data as given, as a sort of black box, without going into the details of their underlying methodologies and patent linkages. However, different definitions of patent families may lead to different results. One of the purposes of this paper is to compare the most commonly used definitions of patent families and identify factors causing differences in family outcomes. Another objective is to shed light into the internal structure of patent families and see how it affects patent family outcomes based on different definitions. An automated characterization of the internal structures of all extended families with earliest priorities in the 1990s, as recorded in PATSTAT, found that family counts are not affected by the choice of patent family definitions in 75% of families. However, different definitions may really matter for the 25% of families with complex structures and lead to different family compositions, which might have an impact, for instance, on econometric studies using family size as a proxy of patent value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Subsequent filings have received multiple names in patenting studies, including external patents, external equivalents, equivalents, duplicated patents, multiple applications, secondary filings or patent family members. In this paper we use the term patent family member to refer to any patent included in a family, which comprises first filings (also called earliest priority filings) and subsequent filings. The term patent equivalent is used to characterise a specific type of family, as described in “Patent family definitions” section.

To our knowledge, the very first efforts to construct patent families date back to the 1940s and were undertaken by Monty Hyams, the founder of private information provider Derwent. He started to publish data on patent families limited to the chemical sector and in the mid 1970s extended his analysis of patent families to all technologies and an increasing number of countries. The Derwent database was the only private source for international patent data for years. The Institut International des Brevets (IIB) in The Hague also began building patent families in the 1970s, before it became part of the European Patent Office in 1978.

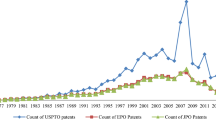

Apart from commercial providers such as Derwent or Questel, the European Patent Office publishes information on patent families online on its website esp@cenet and produces since 2006 the Worldwide Patent Statistics Database PATSTAT (at the request of the Patent Statistics Task Force led by the OECD, which includes the EPO, USPTO, JPO, WIPO, NSF and the European Commission). Ever since it was first released, PATSTAT includes raw data on patent priority linkages and since 2008 it also produces ready-made tables on patent families. The OECD provides raw data on triadic patent families and publishes aggregate statistics online. The WIPO publishes aggregate family data annually since 2008.

In 2001, the OECD developed a methodology to produce the OECD triadic patent families defined as a set of patents taken at the EPO, the JPO and the USPTO to protect a same invention. Statistics of triadic patent families are published regularly at www.oecd.org/sti/ipr-statistics.

Other authors have proposed other alternatives. For example, Sternitzke (2009) proposes to change the definition of triadic families. His proposal consists of adding filings at the German and Chinese patent office to the triad in order to take account of the importance of these two markets for specific technologies (reflected in the growing number of foreign filings registered in these offices), such as mechanical engineering for Germany, and telecommunications and mechanical engineering for China.

More recently, Deng (2007) examined the joint patent designation-renewal behaviour of EPO applicants finding that European patents granted through the EPO are substantially more valuable than those granted through the national route. She also found that the value distribution of patents is highly skewed (even more so for EPO patent families) and increases with the economic size of the country. In turn, van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie and van Zeebroeck (2008) propose a new indicator to measure the value of patents filed at the EPO (the scope-year index) that uses information about the countries where EPO grants are validated (scope) and on the number of renewals paid in each of those countries to maintain the patent alive (age). They stress the importance of considering both dimensions jointly given the dynamic character of patent families, and note that patent value measured at different points in time may provide completely different pictures.

The relation between forward citations and patent value was demonstrated by Harhoff et al. (1999), who showed that the higher the estimated economic value of US and German patents the more forward citations they received, by looking at USPTO patents citing USPTO patents and German patents citing German patents.

The EPO/OECD patent citations database was released in 2004 based on citations received by EPO patent applications and their PCT equivalents and was later extended to citations received by EPO equivalents in the national offices of EPC member states (Webb et al. 2005).

This “economy of citations” at the EPO was already noted by Michel and Bettels (2001, p. 189), “At the European Patent Office, examination experience has shown that most of the relevant information on the above [patentability] criteria is obtained from 1 to 2 documents. According to EPO philosophy a good search report contains all the technically relevant information within a minimum number of citations. This is not necessarily the approach taken by other patent offices.”

“The decision to pursue an application is the result of complex tradeoffs between patent scope and patent value. For an economically important invention, a patent holder may be willing to accept even a highly restricted patent (low scope) while for an economically unimportant one, the patent holder may simply withdraw the application. Applicants with valuable patents can be expected to put more effort into securing a patent grant (even if the claims are narrowed by the examiner during the give-and-take of the examination process).” (Graham and Harhoff 2006, p. 13).

One of the aims of the EPO/OECD workshop on patent families held in Vienna in October 2008 was to compare the outcomes of applying different family definitions to a sample of randomly-chosen patent applications. The experiment showed that differences, if they arise, tend to be related to cases where multiple priorities are claimed. Participants at the workshop distinguished between three types of families (extended; single-priority based; and equivalents) and some examples of filtered subsets (e.g. triadic).

These priority links can be of several types, including Paris Convention priorities, domestic priorities (continuations and divisionals), PCT relations and technical relations. The first three are recorded in patent documents. In contrast, technical relations (also called technical similarities) are additional links identified by patent examiners or database producers based on the similarity of inventions and other characteristics of patents (Martínez 2010).

Data on EPO—Esp@cenet equivalents are available at www.espacenet.com. Inno-tec equivalents are another example available at www.inno-tec.bwl.uni-muenchen.de/personen/professoren/harhoff.

Data on INPADOC extended families are available at www.espacenet.com and PATSTAT.

Data on single first filing based families are available at www.trilateral.net/tsr (based on the EPO-PRI system) and at www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/statistics/patents (based on the WIPO definition).

Based on the presentation by Fenny Versloot-Spoelstra from the EPO at the EPO/OECD workshop on patent families held in Vienna in November 2008. A more complete description is given in Martínez (2010).

Additionally, Simmons (2009) cites typographical errors and changes in database standardization criteria as possible causes of misrepresentation of patent families and differences in family counts across different sources.

Choosing different types of patent linkages (e.g. Paris Convention priorities, continuations, technical relations, PCT links) and patent documents (published vs. unpublished) will also affect final patent counts of families based on similar definitions. For instance, INPADOC extended patent families include both published patent documents and unpublished priorities claimed in them as family members, whereas DOCDB patent families only include published patent documents as members. More information about the impact of these choices and a description of an algorithm to build extended patent families based on patent linkages included in PATSTAT can be found in Martínez (2010).

Statistics based on this kind of definition are regularly released by WIPO (WIPO 2008) and EPO trilateral cooperation statistics (Hingley and Park 2003; Hingley 2009; www.trilateral.net).

Based on the presentations made by Peter Hingley from the EPO and Hao Zhou from the WIPO at the EPO/OECD workshop on patent families held in Vienna in November 2008. There might be other differences in their methodologies causing differences in patent counts, such as the kind of patent linkages used in EPO-PRI and WIPO single first filing based families, or the patent databases on which their algorithms are implemented. Exploring these possible additional differences is beyond the scope of this paper.

Out of the 165,763 INPADOC extended families (excluding singletons) with more than one earliest priority in 1991–1999, 41% have their origin in Japan, 27% in the United States and 7% in German. The remaining countries have lower shares.

The shares of singletons in INPADOC extended families for Japan and the UK are high possibly due to lack of relations among applications or to lack of information about relations in the database. Indeed PATSTAT does not have complete information on divisional applications filed at the JPO (Martínez 2010), but, to our knowledge, it includes all patent information from filings at the UKPO.

As regards single first filing based families, it is clear that no consolidation is done at the level of the first filing, since each first filing is considered the “root” of a different family. Whether there is some degree of consolidation of indirect links between subsequent filings would depend on the rules chosen by each data provider.

I am very grateful to Stéphane Maraut for having developed this algorithm.

Counts of INPADOC extended families excluding singletons reported here may differ when other versions of PATSTAT are used, given that new family members are added to existing families as they become published and new patent linkages added to the database. This means that new families can be formed, singletons may become families with multiple members and already existing families can be extended. As noted in the data catalog of PATSTAT September 2008, INPADOC extended priority families are formed by all the applications that “share a priority directly or indirectly via a third application. A 'priority' in this case means a link shown between applications as in tables TLS204_APPLN_PRIOR (PARIS convention priorities), TLS205_TECH_REL (patents which have been technically linked by patent examiners on the basis of similar content) and table TLS216_APPLN_CONTN (continuations, divisions etc.).” Data on the INPADOC families themselves are available in table TLS219_INPADOC_FAM. The analysis in this paper is limited to patent families with earliest priorities after 1990 and before 2000. This ensured that data on patent linkages from PATSTAT were as complete as possible and that sufficient time was allowed for patent families to form. As regards the first issue, the following warning is included in the Data Catalog of PATSTAT September 2008: “Note that before 1991, the EPO did not record the so called “linkage type” of priority numbers, that is the EPO did not record which kind of relation a given priority number has (Paris Union priority, continuation, division, etc.). Data in this element prior to 1991 is thus not reliable.”

The correspondence is based on one of the IPC classes of the earliest priority of the family or of the subsequent filing with the oldest filing date, if there is no information on IPC for the earliest priority. For more information on the WIPO-IPC correspondence see www.wipo.int.

Domestic families are quite frequent in the US and Japan. Non-domestic families tend to be relatively more frequent in Europe than in Japan or the US, reflecting the fact that European countries have a regional office, the EPO, so that the first foreign filing for most European applicants, after a priority filing in their home countries, is made at the EPO (Frietsch and Schmoch 2010).

The priority date and country of a family with multiple first filings, as the one represented by Structure ID 8, are those of the first filing having the earliest filing date.

It is not uncommon to find patent applications at the EPO filed by Japanese applications that claim more than one Japanese priority. The difference in scope between applications filed at the JPO and in other offices is mainly due to a historical restriction on the number of claims allowed per patent that was annulled at the end of the 1980s (until 1988, the JPO allowed only one claim per patent).

The share of simple and complex families is different for the samples of families matched to technology fields and top priority countries in Appendix Table 6, at roughly 74% and 26%, respectively. As regards technology fields, this is because the WIPO-IPC correspondence leaves out some IPC classes (which would mean leaving out of the analysis the patent families having those IPC classes), and in the case of top priority countries, it is because families with priorities in offices other than the top 5 are left out of the sample used for the analysis.

References

Adams, S. R. (2006). Information sources in patents (2nd ed.). Munich: K.G. Saur.

Deng, Y. (2007). Private value of European patents. European Economic Review, 51, 1785–1812.

Dernis, H., Guellec, D., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2001). Using patent counts for cross-country comparisons of technology output. OECD STI Review, 27, 129–146. Paris: OECD.

Dernis, H., & Khan, M. (2004). Triadic patent families methodology. OECD STI Working Paper 2004/2.

EPO. (2009). Guidelines for examination in the European Patent Office. Available at www.epo.org, April 2009.

Faust, K., & Schedl, H. (1982). International patent data: their utilisation for the analysis of technological developments. Workshop on patent and innovation statistics. Paris: OECD.

Frietsch, R., & Schmoch, U. (2010). Transnational patents and international markets. Scientometrics, 82(1), 185–200.

Graham, S., & Harhoff, D. (2006). Can post-grant reviews improve patent system design? A twin study of European and US Patents. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 5680. London: CEPR .

Grupp, H. (1998). Foundations of the economics of innovation. Theory, measurement and practice. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Grupp, H., Münt, G., & Schmoch, U. (1996). Assessing different types of patent data for describing high-technology export performance. In Innovation, patents and technological strategies (pp. 271–287). Paris: OECD.

Guellec, D., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2004). Measuring the globalisation of technology. An approach based on patent data. CEB Working Paper 04-13.

Harhoff, D. (2006). Patent constructionism: Exploring the microstructure of patent portfolios. Presentation prepared for the EPO/OECD conference on patent statistics for policy decision making, Vienna, October 23–24, 2006. Available at http://academy.epo.org/schedule/2006/ac04/_pdf/monday/Harhoff.pdf.

Harhoff, D., Narin, F., Scherer, F. M., & Vopel, K. (1999). Citation frequency and the value of patented inventions. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 81, 3, 511–515.

Henderson, R., & Cockburn, I. (1993). Scale, scope and spillovers: The determinants of research productivity in ethical drug discovery. Working Paper 3629-93. MIT and NBER.

Hingley, P. (2009). Patent families defined as priority forming filings and their descendents. Working paper available at http://forums.epo.org/patstat under “work in progress”.

Hingley, P., & Nicolas, M. (1999). Improvements to methods for forecasting patent applications using information on patent families. Unpublished paper presented at the international forecasting symposium, Washington, DC.

Hingley, P., & Nicolas, M. (Eds.). (2006). Forecasting innovations: Methods for predicting numbers of patent filings. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Hingley, P., & Park, W. G. (2003). Patent family data and statistics at the European Patent Office. Paper presented at the WIPO–OECD workshop on statistics in the patent field, Geneva. Available at http://www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/resources/studies.html.

Martínez, C. (2010). Insight into different types of patent families. OECD Science and Technology Working Paper 2010/2.

Michel, J., & Bettels, B. (2001). Patent citation analysis. A closer look at the basic input data from patent search reports. Scientometrics, 51(1), 185–201.

Nanu, D. (2003). The Derwent patent family and its application in patent statistical analysis. Presented at the WIPO–OECD workshop on statistics in the Patent Field, Geneva.

OECD. (2009). Patent statistics manual. Paris: OECD.

Pakes, A., & Schankerman, M. (1984). The rate of obsolescence of patents, research gestation lags, and the private rate of return to research resources. In Z. Griliches (Ed.), R&D, patents and productivity, NBER Conference Series. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Putnam, J. (1996). The value of international patent rights. PhD thesis, Yale University.

Simmons, E. S. (2009). ‘Black sheep’ in the patent family. World Patent Information, 31, 11–18.

Sternitzke, C. (2009). Defining triadic patent families as a measure of technological strength. Scientometrics, 81(1), 91–109.

van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B., & van Zeebroeck, N. (2008). A brief history of space and time: the scope-year index as a patent value indicator based on families and renewals. Scientometrics, 75(2), 319–338.

van Zeebroeck, N., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2008). Filing strategies and patent value. CEB working paper 08-016 and CEPR discussion paper 6821.

Webb, C., Dernis, H., Harhoff, D., & Hoisl, K. (2005). Analysing European and international patent citations: A set of EPO patent database building blocks. OECD STI Working Paper 2005/9. Paris: OECD.

WIPO. (2008). World patent report: A statistical review. Geneva: WIPO.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Stéphane Maraut for his comments and for developing the algorithm to characterize and classify different internal patent family structures for INPADOC extended families using raw data from PATSTAT. Hélène Dernis, Dominique Guellec, Peter Hingley and Rainer Frietsch provided helpful suggestions and comments on the OECD/STI Working Paper 2010/2 “Insight into different types of patent families” which introduces some of the ideas presented here, together with a more complete analysis of different types of patent families which benefitted from the discussions held at the EPO/OECD patent families workshop held in Vienna on 20–21 November 2008. Support from the OECD and the Spanish Government through the Ministry of Science and Innovation (CSO2009-10845) is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez, C. Patent families: When do different definitions really matter?. Scientometrics 86, 39–63 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0251-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0251-3